5

Maturing Period

Joseph Schenck’s 1925 move to United Artists was intended, in part, to cover the loss of UA founding partner D. W. Griffith, who had left the company the previous year. Apart from the absence of Griffith’s own pictures, there was a general shortage of product that threatened UA’s very existence. Neither Douglas Fairbanks nor Mary Pickford could deliver more than one feature a year, and Charlie Chaplin’s output had become even less frequent. In the press, it was pointed out that UA, without Griffith, would probably produce no more than three or four pictures a year—not enough to justify a network of exchanges. Even with Schenck, Norma Talmadge’s move to UA would be delayed until she had fulfilled her commitment to First National, a process that would take two years. In accepting the chairmanship of United Artists, Schenck agreed to serve without compensation while reserving the right to produce for UA distribution as many as six features a year. To gear up for such a schedule, he formed Art Finance Corporation, which served as the nominal producer of The Eagle. Then Art Finance created Feature Productions, Inc. to function as a production entity, and Schenck, in a bold move, assigned it Valentino’s contract.

Menzies, as a Schenck employee, would be allocated to the Talmadge pictures as well as Feature Productions. He found his first job under the new pact would indeed be a Talmadge project—the Belasco stage success Kiki, for which Schenck had reportedly paid the record price of $75,000. A dispute over the picture rights had stretched years, with Broadway star Lenore Ulric determined to re-create the role on-screen she regarded as her own personal favorite. That Norma Talmadge had never before played comedy made the eventual sale—with Talmadge stipulated as star—a particularly bitter loss for Ulric, who angrily left Belasco’s management in retaliation. Spinning the press coverage, Schenck announced “an unprecedented array of technical genius” to collaborate on the picture—Clarence Brown as director, Hans Kraly as scenarist, William Cameron Menzies as designer of “settings and art effects.”

That same day, August 30, 1925, Menzies departed for New York and Paris, where he would confer with Belasco’s longtime designer Ernest Gros, the man who created the scenery for the original 1921 Broadway production, and study the Aztec motifs of the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes, the modernist World’s Fair that was already revolutionizing the fields of architecture and applied arts.

In Menzies’ absence, Schenck announced the first of Feature Productions’ new slate of films—the long-awaited screen version of The Bat, the phenomenal Broadway stage success that had since become a perennial favorite in dramatic stock. Dubbing it “perhaps the world’s most famous mystery play,” the Los Angeles Times reported the highest price paid that year “for a play or story to be picturized as an independent production.” Writer-director Roland West was credited with effecting the purchase, the owners having declined all previous offers because the play had remained such an extraordinary moneymaker. “West put over the coup only after weeks of negotiations and by offering a huge sum,” explained the newspaper. Schenck and Art Finance came in on the deal as a source of capital, and West released his share of the rights in mid-November 1925, concurrent with UA’s release of The Eagle.

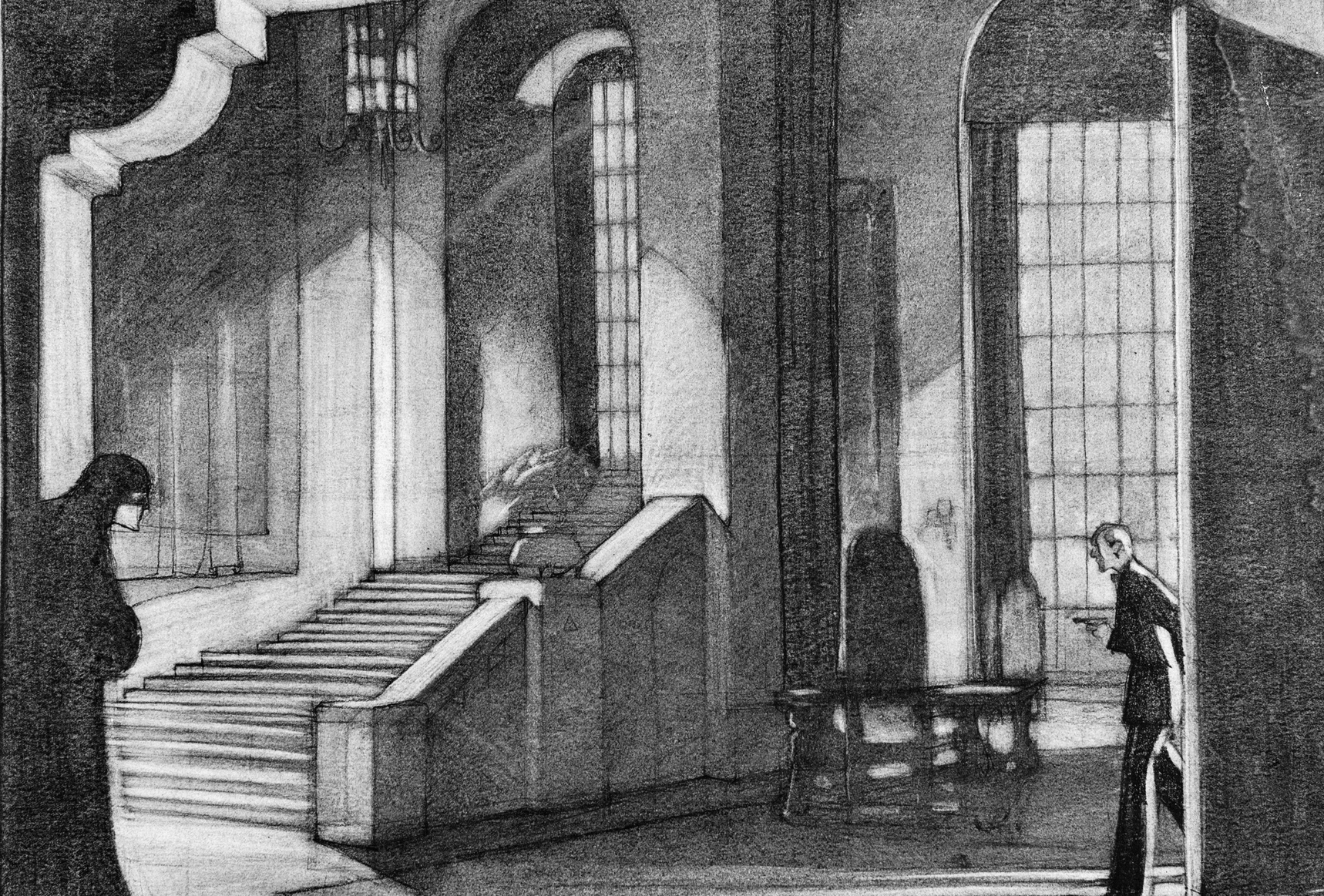

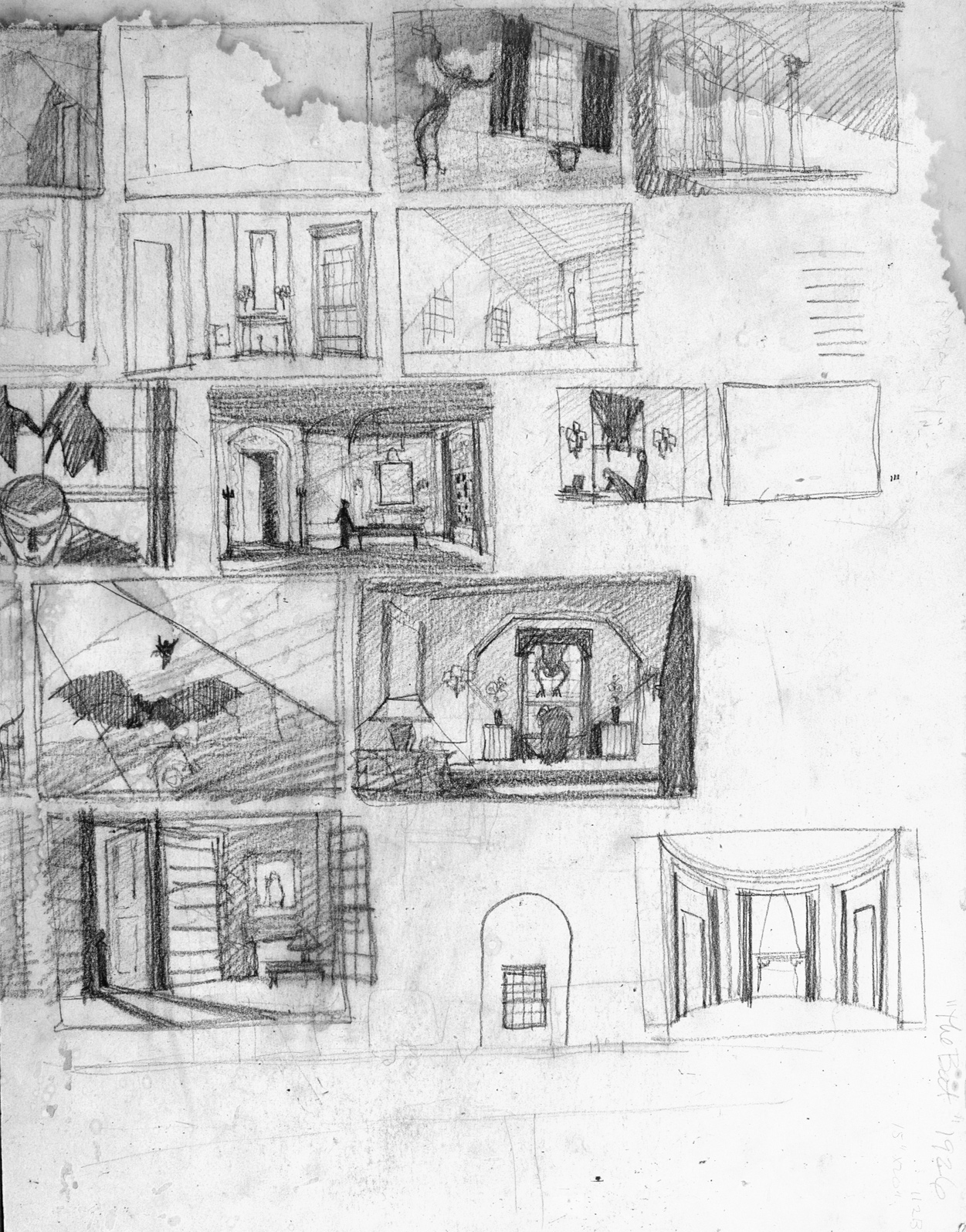

By then, Kiki was well under way, Menzies having given it a luster unequaled in any of Norma Talmadge’s previous vehicles (which tended, despite their prominence, to be low-rent affairs). The story posed no great challenges, though much was made of Menzies’ Paris street scenes, which were lauded for their grace and authenticity. The film’s set piece was the grand home of the Folies Barbes, a modernist theater that reflected the lines and sensibilities of the burgeoning Art Deco movement. Constructed sectionally, the set would support the lengthy tracking shot that opened the film, taking the camera from the rehearsal of “Deauville Daddy” by the revue’s chorus, past stagehands hammering and sawing, sweepers, scenery painters, the old watchman at the stage door, and finally out into the back alley, where the stagestruck gamine Kiki is doing her spirited best to sing along. “Norma was the greatest pantomimist that ever drew a breath,” declared Clarence Brown. “She was a natural-born comic; you could turn on a scene with her and she’d go on for five minutes without stopping or repeating herself.”

The Art Deco home to the Folies Barbes, as conceived by Menzies for Clarence Brown’s production of Kiki (1926)

The actual set, dressed and populated, as it appears in the film (MENZIES FAMILY COLLECTION)

Of far greater concern was The Bat, which would have to live up to its reputation as a timeless thriller while incorporating effects and enhancements that could only be attained on-screen. Schenck afforded West virtual autonomy in developing the film, having known the younger man since their days together in vaudeville when West was touring a playlet called The Criminal and Schenck was acting as his manager. In 1916, they launched their picture careers with Lost Souls, a $26,000 feature starring English actress José Collins. After Schenck took charge of his wife’s career, West became general manager of production and directed Norma Talmadge in De Luxe Annie (1918). That same year, he returned to the stage as coauthor and producer of The Unknown Purple, a crime melodrama with fantastic overtones that became a considerable hit.

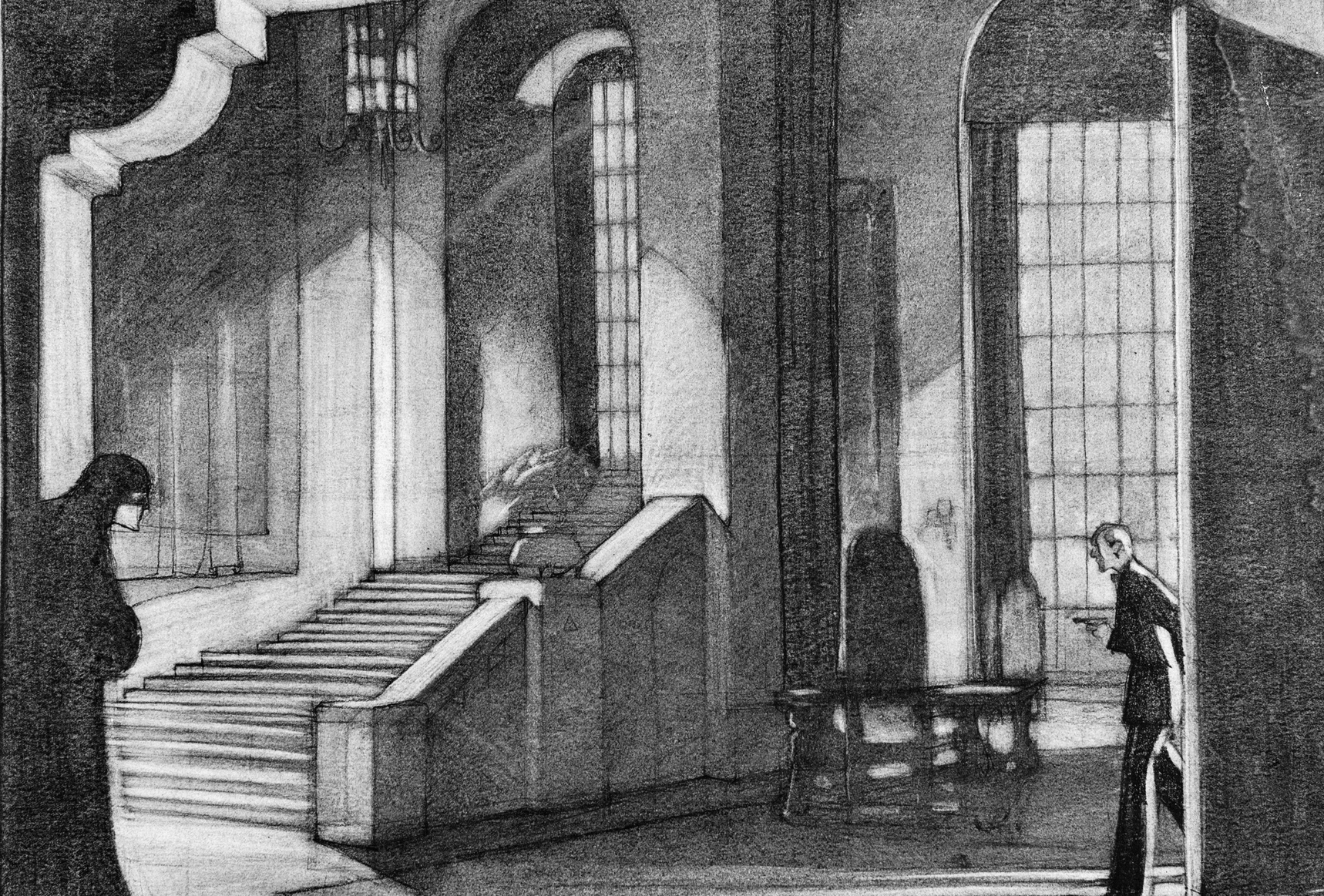

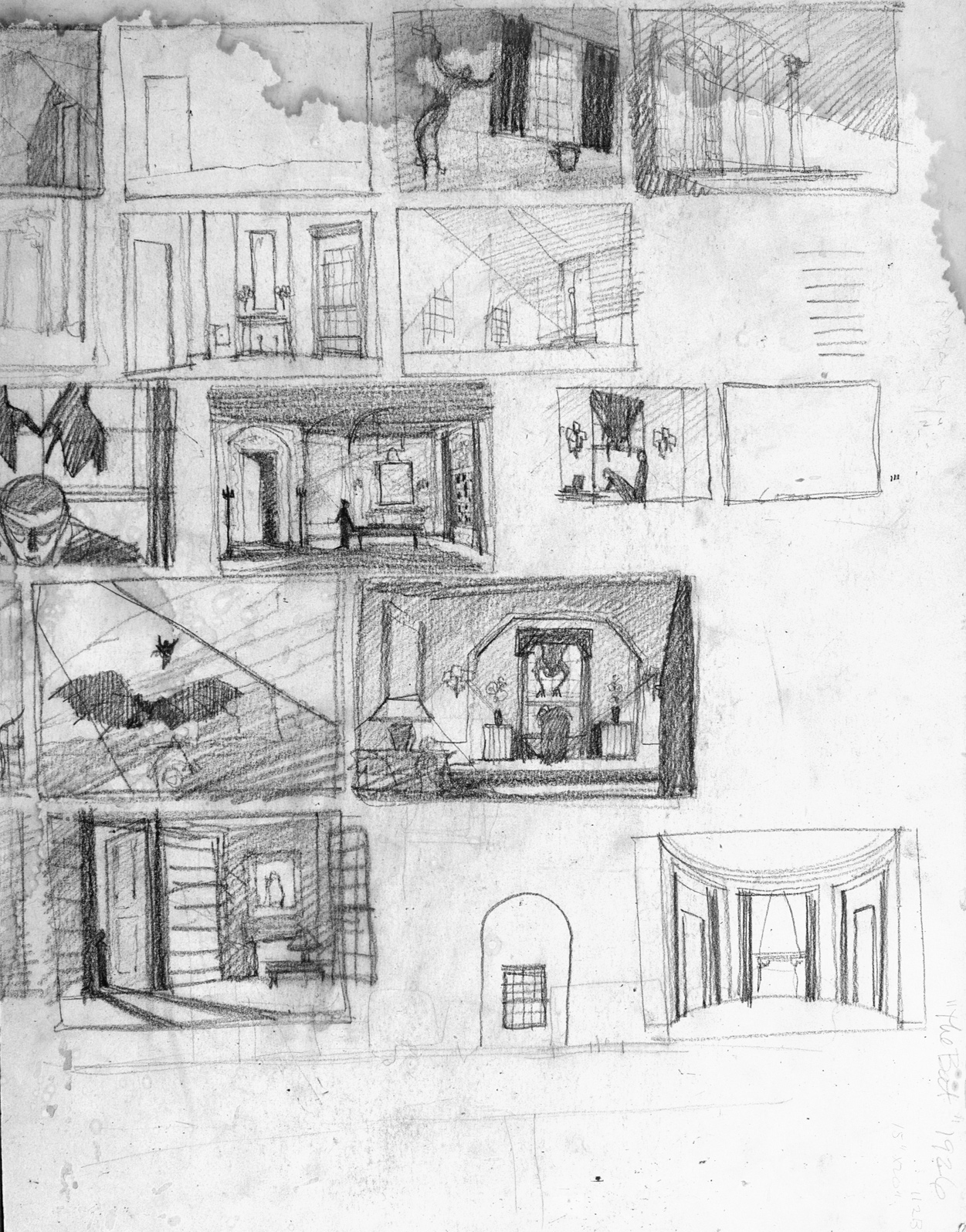

Working up to a December start date, Menzies strove to invest The Bat with a size and scope impossible onstage. What evolved was a mystery of great beauty and elegance, a new way of seeing a genre that had become commonplace in the years since the play opened on Broadway in August of 1920. The story took to the rooftops, an entire city in the background of what had once been the story of the old Fleming mansion alone. Menzies gave the place the sturdy look of a grand manor, its floor space vast, its heights seemingly limitless. Though West failed to take full advantage of the sets, leaving the mise-en-scène largely to the mercy of cameraman Arthur Edeson, the one genuinely jarring difference between Menzies’ conceptual illustrations and the resulting film was in the depiction of the Bat himself. Where Menzies visualized a sleekly caped figure lurking in the shadows, suggesting a bat’s visage in tone and countenance, West imposed a more literal interpretation, giving the character a grotesque face mask, extravagantly fanged and topped with the ears of a raging chihuahua. Such revisions spoke to West’s vaudevillian roots, and kept the picture from emerging as the stylistic triumph it might otherwise have been.

Menzies’ influence is most clearly seen in the film’s opening moments, when the Bat makes good on a threat to steal the famed Favre Emeralds at the stroke of midnight. The sequence sets the tonal palette for the movie—long shadows, stark shafts of light, towering windows, a brooding sense of dread. The murder of Gideon Bell is heralded by the appearance of a gloved hand at an open window, its shade flapping incongruously in the still night air, the killer’s figure framed by the window as he makes his escape, the body of his victim lying crumpled at its base. Menzies sketched this brief prologue, working through a sequence of images on the back of an art board, expressing his thoughts as a series of thumbnails. Refined, they constitute the first time, in all likelihood, that he carried the staging of a scene through to the sequencing of individual shots, a logical progression in technique that was now possible with his status as a salaried employee.

Menzies designed The Bat (1926) to a scale impossible to achieve on the stage. Note the similarity of the caped figure at the left of this drawing to Bob Kane’s later conception of Batman.

(MENZIES FAMILY COLLECTION)

Menzies characterized his five and a half years with Joe Schenck and Feature Productions as a “maturing period” during which he “nearly killed” himself with overwork. In all, he designed the sets for forty-five feature films, either directly under Schenck and Johnny Considine, or on loan-out to other UA producers, Samuel Goldwyn principal among them. Such a workload, he later said, should probably have been allocated to four or five men, but at the time he had only one associate with whom to share the burden, architect and stage designer Park French. Slight and graying, his blue eyes framed by wire-rimmed glasses, French was the more technical of the two, capable of knocking out blueprints as well as renderings, an industrious man who spent his later years designing office buildings. “I never saw him,” said his son Charles, then just seven years old. “He went to work early in the morning and came home late at night.”

The opening of The Bat as worked out in a partial set of thumbnails. On the reverse side of this 20 × 15-inch piece of illustration board is the drawing from the previous page. (MENZIES FAMILY COLLECTION)

Rudolph Valentino’s second picture for United Artists, The Son of the Sheik, looked as surefire as any property could possibly be, a sequel to the actor’s first solo sensation, The Sheik, which broke New York attendance records when it opened in October of 1921. The original had the effect of settling the Valentino image in the public mind, and when the British author Edith M. Hull penned a sequel, it was obvious that only Valentino could play it. The purchase was finalized in December 1925 while Valentino was in Europe, Schenck claiming the results of a canvas showed that “more than 90 per cent of those who expressed an opinion” favored Valentino in The Sheik over his roles in The Eagle, The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, or Blood and Sand. A message from George Ullman caused his client to shorten his European tour and return to California for a March start date.

Considine made every effort to accommodate his star, who was less than thrilled at the prospect of once again playing a part that had dogged him for years. Assigned to direct was George Fitzmaurice, now under contract to Schenck, whom Valentino had wanted for Blood and Sand some four years earlier. Frances Marion, one of the screen’s top scenarists, was put to work on the script, and Vilma Banky, Valentino’s love interest in The Eagle, was again his leading lady. Menzies gave his pal Rudy every consideration, and although Valentino was permitted a dual role as both Ahmed and his bearded father, the Sheik of the original film, economies were imposed that showed most forcefully in the scaled-back look of the sets. Where Menzies envisioned a sort of grand Polynesian-style hut as Ahmed’s desert retreat, light filtering through slatted openings, what showed in the film was more generically accomplished with bolts of fabric, the set devoid of the structural complexities that distinguished his more artful designs.

On location at the sand dunes outside Yuma, Arizona, the furnacelike heat never abated, even at night. The water was brackish, the flies innumerable, and Menzies found that the shifting light undermined the designs he had so painstakingly worked out. “It is usual to lay out a set to the south,” he explained, “because back light is much better. Of course, if you are going to shoot on the set all day, you have to bear in mind the changing position of the sun with relation to the changing action on the set.… We didn’t shoot the picture until three months later and had forgotten to take the changing declination of the sun into consideration. The result was that the lighting was terrible—it was complete back light, whereas we arranged it for a beautiful cross light.” That Son of the Sheik seemed less substantial than The Eagle reflected the somber fact that the latter film hadn’t been the runaway hit it was expected to be, a matter of grave concern to all involved, Valentino in particular.

As Menzies began work on the next Dutch Talmadge comedy, a romantic trifle called The Duchess of Buffalo, Schenck upped his quota with United Artists, agreeing to supply eight to ten pictures a year commencing June 1, 1926. When his partners at Art Finance balked at funding an expanded program, Schenck bought them out and formed Art Cinema Corporation to take over the assets. A First National release, The Duchess of Buffalo would become the first Schenck production to be filmed at the Pickford-Fairbanks studio, where Feature Productions would now be headquartered, and where Menzies would occupy a studio on the second floor of a building that sat between the main gate and Douglas Fairbanks’ barnlike gymnasium.

March of 1926 was momentous in other ways, for a second daughter, Suzanne, was born to the Menzies family on the 11th, further stressing the space limitations of the two-bedroom apartment they occupied on Harper Avenue. Fortunately, relief was at hand in the form of a spacious new home. Along with his work and travel for Schenck, Menzies had designed himself a house every bit as fanciful as one of his sets, and construction had already begun on the parcel of land he had purchased on North Linden Drive, a short walk from the intersection of Wilshire and Santa Monica Boulevards. He was unabashed in his love of Beverly Hills, calling it one of the most beautiful places on earth. “I can remember when there were pine trees growing down Wilshire Boulevard as far as the Old Soldiers’ Home,” he reminisced in 1954. “Those trees were later offered for sale for ten dollars apiece—and all those huge pine trees you see around town were once planted on Wilshire.” With work on his house under way and The Bat now in release, Menzies prepared to tackle the most ambitious assignment Considine had yet given him, an all-encompassing job on the scale of The Thief of Bagdad and The Hooded Falcon, another one of those chances he never again expected to get.

One evening in the spring of 1926, Joe Schenck called on John Barrymore at Los Angeles’ Ambassador Hotel. UA’s golden patina had dulled somewhat with the departure of Griffith, but there was still power in the names of Chaplin, Pickford, and Fairbanks, and no better affiliation for an actor of Barrymore’s artistic and commercial stature. When he left that night, Schenck was pocketing a contract that committed the star of The Sea Beast and Don Juan to two pictures at a rate of $100,000 per, a coup in that Barrymore, coupled with the magic of the Vitaphone, was soon to be recognized as the biggest name in movies. Yet Schenck would not be paying the Great Profile a weekly salary, as had Warner Bros., and knew he would need to keep his new star happy in ways other than strictly monetary. At Barrymore’s behest, Schenck agreed to bring his director, Alan Crosland, to Feature Productions and pledged that Barrymore’s first picture for UA would, in terms of production values, be on a par with The Thief of Bagdad, thus making The Beloved Rogue the third Barrymore “special” in a row.

An attraction also was the opportunity to work again with Menzies, whom Barrymore had known at Famous-Lasky and who would now be re-creating fifteenth-century Paris on the backlot at Pickford-Fairbanks. Menzies tore into the assignment with unusual zeal, even when the writing of the script lagged as Barrymore, Crosland, and assistant director Gordon Hollingshead repaired to Hawaii. According to Barrymore’s biographer Gene Fowler, several scenarists endured the development process before writer-director Paul Bern became the author of record.

Jack Barrymore’s spirited take on Villon, “poet, pickpocket, patriot—loving France earnestly, French women excessively, French wine exclusively,” led Menzies to conclude the character was a little mad. The look of the picture, he therefore decided, should reflect that madness, the sets appearing as Villon himself might have perceived them. Nothing outside the King’s palace would be plumb or symmetrical, as if the walls and rooflines of Paris were active participants in the action, leaning in at times as if to express disapproval and visibly buckling under the weight of the snow. It was an organic sort of architecture, subjective and malleable, a celebration of Villon’s emotional attachment to the city of his birth.

“France in 1451, when François Villon held forth in Paris, is classified architecturally under the Gothic period,” Menzies noted,

and this period signifies a wild, grotesque, bizarre type of construction. The tendency of that age leaned toward long roof lines, sharp angles, twisted stairways, and fantastic sculpture and carving. Cold, harsh, austere lines accentuated the somber feeling of the period, and because of this harshness, it was a peculiarly wild and fanciful type of interesting beauty.… I have endeavored to give the entire background atmosphere personality and character. True, I have diverted somewhat in some instances, from the ethical construction of the period and branched into the mythical, but this was done to enhance the dramatic value of a scene or scenes. For example, in the public square of Rouen, at the time when Joan d’Arc is being burned at the stake, the buildings look down upon the crowd, their frowning eaves throwing a veritable defiance at the King. Again, in the sequence in the kitchen of the Inn, where an atmosphere of comedy prevails, the ovens and the chimneys are of a rounded, rather squatty and rotund design, typifying a light trend of thought—comedy. And in some of the highly dramatic exterior scenes driving snow augments the realism of the setting.

Menzies would share a card with Bern in the opening titles for Beloved Rogue, the twin functions of plotting and design linked as the collaborative enterprise they ideally were. By stepping away from the mash of technical credits in which he typically found himself, Menzies also worked free of his usual “Settings” credit, advancing to the more formal title of Art Director. It was a major move forward, an acknowledgment that what he did was part of the storytelling process and not simply arrived at in a vacuum. For Beloved Rogue he supervised the fabrication, texturing, and painting of the sets, remaining with the picture, as he had with Thief of Bagdad, through a production schedule that stretched twelve weeks. When completed, The Beloved Rogue was a masterpiece of craft and synthesis, one of the most distinctive pictures to emerge from Hollywood in the waning days of the silent film.

For much of The Beloved Rogue, the contours of Villon’s Paris are shrouded in snow—it shields him, embraces him, nurtures him. Here, the King’s provision wagon makes a stopover at a tavern called the Over-Ripe Grape, where the poet and his men will seize the opportunity to commandeer it. (MENZIES FAMILY COLLECTION)

The Beloved Rogue was in production when Menzies took occupancy of the house on Linden Drive. Suzanne Menzies, then an infant, later described the place as “French Normandy in design, English Tudor in reality.” It was, in fact, a marvel of architectural salvage, incorporating a huge pair of doors from the set of Cobra as well as a number of decorative features, relief plaques, and curved finials that had first been conceived of for the sets of his movies. “Daddy was so proud of that house,” said Suzie.

They had just finished it; it was a charming house. He was out in the yard one day, and Anton Grot drove by. And stopped to talk. Daddy invited him into the house, and Grot said, “No thank you. I don’t like the outside, and I know I wouldn’t like the inside.” Daddy was just crushed.

He and Bill Flannery, who had worked for him [and who was trained as an architect], designed it. Totally impractical. For instance, when you had all the dining room windows open, you couldn’t walk around the dining room table because they all opened in. And in 1926 the kitchens were pretty awful. Not enough bathrooms.… But it was a great house to give parties in. The living room, which was originally supposed to be his studio, was out of this world—beamed ceilings, window seats. Very warm, very inviting. Everybody loved it. Lon Chaney built a house next door, but he didn’t live there very long. I don’t think Mother ever talked to his wife. She was always scared that he would pop out of the bushes with one of his makeups on and scare my sister. Mother could always anticipate the worst of anything.

The following year, Menzies designed a fanciful cliff dwelling for Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks, an eight-level seaside retreat gripping an almost vertical plot of land at Solana Beach, the construction of which costed out at $125,000. It was lovely, Pickford noted, but wholly impractical. Later, John Barrymore, contemplating marriage to actress Dolores Costello, would ask Menzies to supervise the design of a six-room addition to his Tower Road estate. (“Just in case I want to have a larger house,” the actor hedged.) In general, Menzies seemed to regard architectural design in the same way he did set design, hewing toward the beautiful and the visually arresting and giving short shrift to the demands of livability. Of the small number of structures he designed that were never intended to be seen on a motion picture screen, the house at 602 North Linden would be the only one ever built.

The settling of the family homestead coincided with a relatively easy job, the staging of a modern-dress Camille for Norma Talmadge. Schenck had high hopes for his wife’s last First National release, a sop to the matinee trade. (“I want Norma to catch fire in this picture,” he declared as he trashed a draft scenario by Frances Marion.) Menzies delivered the opulence of Marguerite’s famed bedroom and bath, the Mataloti ballroom, and the casino adjacent. The picture would hit its mark, returning a domestic gross of more than $800,000, but the crucial result for Joe Schenck and United Artists would be his wife’s very open affair with her younger leading man, the darkly handsome Gilbert Roland.

Menzies’ interiors for The Beloved Rogue were in harmony with the action, squat and rounded in lighter moments, dense and forbidding at times of peril. “There will be no need for new experiments in camera angles in the filming of this picture,” the editors of Motion Picture magazine concluded, “for the curious angles are supplied by the sets themselves.”

(MENZIES FAMILY COLLECTION)

Talmadge and Schenck had always been regarded in Hollywood as an odd couple, Norma cool and slightly bored with it all, the squat, homely Joe resembling, in the words of Gloria Swanson, “a second-hand furniture salesman.” She was, according to Anita Loos, never really in love with Joe, although she did allow him the privilege of adoring her. “Together,” said Loos, “they looked like Snow White and an overgrown dwarf; Joe’s figure was portly, he was beginning to go bald, and he suffered a cast in one eye that gave him a permanent squint. But these were only surface faults; in every other way Joe was most engaging; he had the subtle masculine allure which so often accompanies power, and he used his power with the greatest consideration for others.”

All of this might have cast a pall on Talmadge’s long-awaited arrival at UA, but Schenck, refusing the offers of his gangster friends to rub out his rival, decided instead to double down, returning Roland to his wife’s arms for a second picture and giving Menzies carte blanche to create yet another land all its own for the film version of Willard Mack’s Broadway melodrama The Dove. Facing foreign government protests and the threat of a boycott, the locale for the picture was shifted from rural Mexico to the mythical country of Costa Roja (“somewhere on the Mediterranean coast”) where Dolores, the dance hall gal known widely as “The Dove,” works a cantina called the Yellow Pig. With license to distance the story from its original setting, Menzies created a sort of Bagdad by the Sea, harsh and magical and otherworldly, and yet unmistakably Mexican in tone and texture. Complementing the flair and color of the designs would be the outsized performance of Noah Beery as Don José María y Sandoval, the brutish caballero who lusts after the Dove and frames her sweetheart, a gambler named Johnny Powell, on a phony charge of murder in his drive to possess her.

For the picture, Menzies found himself working once more with Roland West, who again permitted him to design and essentially direct an opening sequence as he had earlier done for The Bat. The nighttime scene opens on a bakery and the entrance of Gómez, one of Sandoval’s lieutenants. A beggar attempts to steal a loaf of bread, his starving wife in the background urging him on. Gómez takes in the scene, stops the man, and grandly loads his arms up with bread. As the recipient, quivering with gratitude, turns to make his exit, Gomez draws his pistol and shoots him dead. “I have been kind to the poor fellow,” he reasons, holstering the weapon. “He will never be hungry again.” A deep focus shot completes the prologue, the story told, after the manner of a three-act drama, on three planes working from back to front: the figure of the hysterical woman grieving over her husband’s body in the background, the killer and the clerk chatting amiably in middle distance, and a bug sprayer dominating the foreground, a skull and crossbones and the word VENENO gracing the metal can, the lines of composition drawing these elements together in a low-angle tableau of casual brutality.

The house Menzies built on North Linden Drive was as distinctive as it was impractical.

The grand caballero’s hacienda for The Dove (1927). The Mexican locale of Willard Mack’s famous play, changed for political exigencies to a mythical land on the Mediterranean, helped win for Menzies the first Academy Award ever presented for art direction. (MENZIES FAMILY COLLECTION)

The scenario was primarily the work of Wallace Smith, a newsman and novelist who held the rank of colonel from his campaign days in Mexico and Central America during the time of Pancho Villa. Having also illustrated Ben Hecht’s Fantazius Mallare and The Florentine Dagger, Smith spoke the same artistic language as Menzies, and the two men effected a shorthand collaboration as the movie took shape. In the end, it was Menzies’ design of the film that earned the most plaudits, with Talmadge’s lackluster performance and Gilbert Roland’s obvious miscasting noted in most every review. Menzies would later stress the importance of setting in the dramatic impact of a picture, especially in an instance where the actors weren’t pulling their collective weight.

The art director and the cameraman, with their many mechanical and technical resources, can do a great deal to add punch to the action as planned by the director. For example, if the mood of the scene calls for violence and melodramatic action [as in the opening of The Dove], the arrangement of the principal lines of the composition would be very extreme, with many straight lines and extreme angles. The point of view would be extreme, either very low or very high. The lens employed might be a wide-angled one, such as a twenty-five millimeter lens which violates the perspective and gives depth and vividness to the scene. The values or masses could be simple and mostly in a low key, with violent highlights.… [W]hen the tempo of the action is very fast, there are usually rapidly changing compositions of figures and shadows.

Nineteen twenty-seven would be another big year, with the release of The Beloved Rogue in March and work on six additional pictures—Topsy and Eva, Two Arabian Knights, Sorrell and Son, Sadie Thompson, Drums of Love, and The Garden of Eden. For the independently produced Two Arabian Knights, Menzies recycled sets from The Son of the Sheik and consulted on location work in the snows at Truckee. With Drums of Love, he began a four-picture association with D. W. Griffith, a seemingly momentous occasion of which he never spoke. (“He was receptive, a good man, though he was then past his peak,” cinematographer Karl Struss, who shot the film, said of Griffith.) In some cases, as with Topsy and Eva and Sorrell and Son, Menzies designed the necessary settings and was uninvolved in the shooting of the films. For others, such as Sadie Thompson, where he was reunited with Raoul Walsh, he consulted on the script and was present throughout production—to his mind the ideal arrangement.

“In the first place, although not customary, it is of great advantage to the art director to know something of the story as it is being constructed,” he said in describing the development process.

Very often he will have many valuable suggestions to offer.… When reading the scenario, notes are made, and if there is sufficient time rough sketches of the separate scenes are prepared. After consultation with the cameraman and director and the incorporation of their suggestions, the art director works up his sketches into presentable drawings. He considers such things as point of view, nature of the lens to be used, position of the camera, and so forth. If he is concerned with intimate scenes, he concentrates on possible variations of composition in the close shots. If he is designing a street, or any great long shot, he considers the possibility of trick effects and miniatures, double exposures, split screens, traveling mattes, and so forth. When the drawing is finished, the director, cameraman, and designer confer again, and when all interested are satisfied with the drawing, it is projected through the picture plane, to plan and elevation. This process reproduces the composition line for line, and retains all the violence or dramatic value of the sketch, even with changed point of view. The finished plan and elevation is blueprinted and sometimes transposed into a model and turned over to the construction department.

Improvements valued at $2 million were nearing completion on the Pickford-Fairbanks lot, soon to be renamed the United Artists Studio, when John Considine announced the purchase of an additional sixty acres in nearby Culver City for an “auxiliary plant.” Considine was also beefing up the contract talent, signing writers such as Donald McGibeny and F. Scott Fitzgerald to term agreements, and adding actor Michael Vavitch to a stock company that now included Estelle Taylor, Gilbert Roland, and Walter Pidgeon.

UA was so short of releasable product that Schenck gave a distribution contract to the fledgling producer Howard Hughes, who had no track record to speak of but could finance his own films. It was through his attorney, Neil McCarthy, that Hughes met John Considine, and it was Considine who led him to director Lewis Milestone. A former cutter, Milestone had a good sense of pacing and an exceptional eye. Two Arabian Knights wasn’t as costly as it looked, the casting of actor William Boyd its only true extravagance, but the jaunty comedy was a surprise hit, a critics’ darling, and a genuine credit to UA in a year when only four movies carried the firm’s imprint.

Considine soon had the Russian-born Milestone back for a second picture, a Corinne Griffith comedy after the fashion of Dutch Talmadge, whose own career was winding down. The Garden of Eden was again by Hans Kraly, but Milestone, teamed with Menzies, proved a stronger visual stylist than Sidney Franklin, certainly more collaborative. He delighted in posing problems to be solved with a camera angle, an adroit grouping of actors, or the design of a set to make a comedic point or serve as a visual punch line. “The set itself often causes a laugh,” Menzies noted. “In … Garden of Eden there is a place where a couple starts an argument after they are in bed and every time they sit up to argue they turn on the light. There was a man living across the court, and he noticed the light going on and off and thought somebody was signaling and began to flash his light on and off. Then other people saw it and did the same. We made a miniature of the complete side of a hotel and all the windows were flashing lights. It caused a great laugh.”

Menzies sketched gags for Milestone, rendering them “almost in the mood of caricature.” Stylistically, his individual panels resembled storybook illustrations, the compositions accomplished with figures rather than structural forms, a significant advancement from his earlier work. It was the closest he had yet come to actually directing actors, and the exercise betrayed an inclination to see them more as graphic elements than fellow artists. “With all due respect to Miss Griffith,” wrote William K. Everson in program notes for a 1957 screening, “perhaps the real star of The Garden of Eden is William Cameron Menzies.”

Less ambitious in terms of design, yet certainly one of the year’s most notable pictures was Sadie Thompson, the Gloria Swanson vehicle in which Raoul Walsh would be costarring as well as directing. Walsh hadn’t acted in a film since 1915 (the year he played John Wilkes Booth in The Birth of a Nation) and would doubtless want Menzies on hand when shooting scenes that required him to be in front of the camera. Filming began in July 1927, with the pace of work hampered by the replacement of cinematographer George Barnes when he was recalled by Sam Goldwyn one week into production. Robert Kurrle replaced him at first, then Oliver Marsh took over from Kurrle when the latter’s interior work was found wanting. Menzies’ principal contribution was the weary, rain-soaked hotel in Pago Pago where much of the action takes place, a tropical exterior built on a stage at United Artists. “We covered the floor of the stage with dirt, grass, and leaves to give the effect of the ground outside the hotel,” he recalled, “but when we turned on the rain effects it was all washed away and we had to cast the whole thing in cement.”

Plaster and cement had become the basic textural elements of movie sets, able to catch and cheaply replicate an endless array of surfaces. “Texture is a rather interesting subject,” Menzies said at the time.

All our straight plaster textures are cast in sheets nailed to a frame and then pointed or patched with plaster. Brick, slate roofs, stone work, and even aged and rotted wood are casts taken from the original thing, made in sheets and applied. That is, if we have a stone wall, we get a lot of stone and build up a wall about six feet high, put the plaster cast on it, and peel it off like you do a cast from a tooth. You can cast any number of pieces of wall from that. The painting is usually done by air guns, and in many cases the light effects are put on by expert air gun operators.

Toni Lebrun’s debut at the Palais de Paris in Budapest …

… is sabotaged when a light switch is thrown backstage. This is one of the many sight gags devised by Menzies for The Garden of Eden (1928). (MENZIES FAMILY COLLECTION)

The Sadie Thompson company spent a month on Catalina Island, where the Pago Pago wharf scenes were filmed. While on location, Menzies took part in Sadie’s arrival as an extra. Here he poses in costume with director Raoul Walsh and Gloria Swanson. At far right, ignoring it all, is Lionel Barrymore. (MENZIES FAMILY COLLECTION)

He finished out the year with total immersion in another far-off land, a task rendered all the more difficult by the fitful shifting of personnel. When first announced, the John Barrymore vehicle Tempest was an original story by Mme. Fred de Gresac, the French playwright who had previously shared an adaptation credit on Son of the Sheik and had taken Frances Marion’s place on the Talmadge version of Camille. Directing the script, touted as providing Barrymore his first modern screen role in five years, would be Frank Lloyd, late of Paramount. The title stuck, but little else did. Lloyd fell away sometime over the spring of 1927, as did Mme. de Gresac’s material, and Russian émigré Viktor Tourjansky, under contract to Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, replaced him. The new story, set at the time of the Russian revolution, was supplied by Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko, Tourjansky’s mentor at the Moscow Art Theatre. It was Tourjansky who selected the Russian actress Vera Voronina to be Barrymore’s leading lady and imported actor Boris de Fas (from his own Michael Strogoff) for the role of a wild-eyed Bolshevik. As veteran scenarist C. Gardner Sullivan got down to work on a screenplay, Menzies began the process of illustrating key sequences with Tourjansky.

Filming commenced in October but didn’t go well from the start. “Tourjansky was a perfect delight to work with,” said cameraman Charles Rosher. “He had a camera eye, great taste, and a fine imagination. But he wasn’t fast enough.” Voronina fell ill after two weeks, shutting down the production. Then it was announced to the trade that Lewis Milestone was going to lend Tourjansky “a helping hand.” Actress Dorothy Sebastian was borrowed from M-G-M to replace Voronina, but then Considine pulled the plug when it became apparent that Milestone and Menzies were, in effect, doing Tourjansky’s job for him. Sebastian was sent back to Culver City, to be replaced, it was hoped, with the German actress Camilla Horn, for whom the part of the Princess Tamara had supposedly been written. (Horn, said Rosher, was Joe Schenck’s mistress at the time.) Production resumed in December with the unlikely choice of Sam Taylor as the new director. “I don’t know anything about Russia,” the former gag man for Harold Lloyd admitted to Considine. “That’s all right,” the producer assured him, confident that Menzies had already done most of the heavy lifting.

Taylor had no visual style to speak of, but he had a way of injecting sly comedy into otherwise breathless drama that appealed to both Barrymore and Considine. Taylor scrapped all but a single Tourjansky sequence and began anew, working far more closely with Menzies’ illustrations than with the script Sullivan had fashioned. “You get your perspective while you’re working,” Taylor said, “and only then. You can’t build convincing climaxes on paper. They develop of themselves.” Three weeks into filming, Camilla Horn finally reached Hollywood, and Taylor found himself directing her through an interpreter.

For Tempest, Menzies rendered a less stylized version of Russia than he had for The Eagle, but one far more comprehensive. He would later speak of the importance of setting and lighting in securing a desired effect, and how, in many cases, authenticity was sacrificed and architectural principles violated for the sake of the response being sought. “My own policy has been to be as accurate and authentic as possible. However, in order to forcefully emphasize the locale I frequently exaggerate—I make my English subject more English than it would naturally be and I over-Russianize Russia.”

The picture began with a bird’s-eye view of Volinsk, a garrison town near the Austrian border, an elaborate miniature constructed on a giant turntable, the camera closing in on the midnight quarters of Sergeant Ivan Markov. Moody images of Imperial Russia in its final days, sturdy, low to the ground and smothered in snow, were contrasted with scenes of pomp and ceremony, capturing the brittle world of the aristocracy and melding seamlessly with later shots as seen through the bars of Markov’s prison window. Menzies once estimated that he made more drawings for Tempest than for any previous film, and the consistency of its look belies the fact that it had multiple directors, a trio of leading ladies, and a well-earned reputation for being, as the Los Angeles Times put it, a “bad luck film,” ill-starred and seemingly as doomed as the czarist era it portrayed. Its final cost came to $1,041,048—extraordinary for the period.

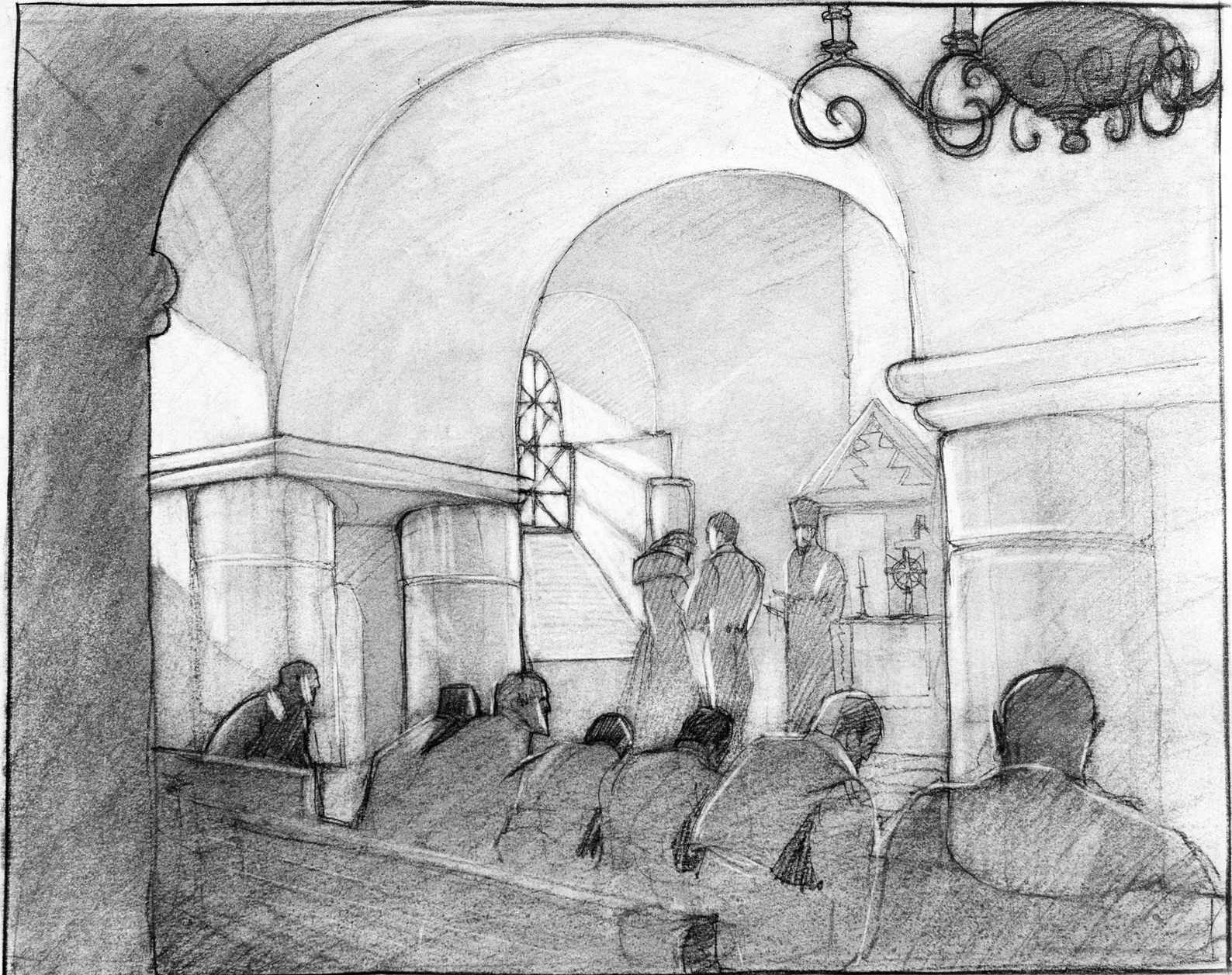

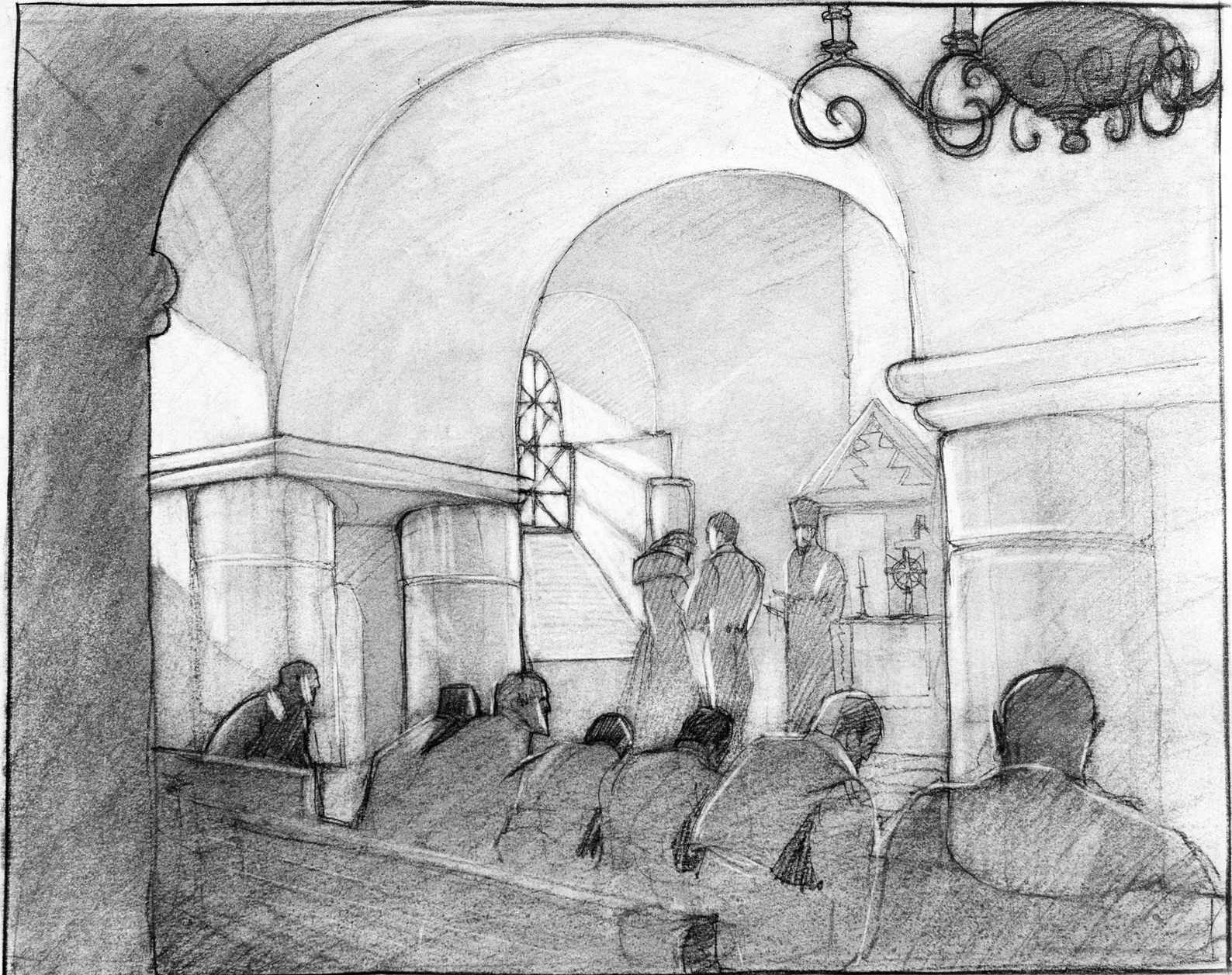

The wedding of Ivan and Princess Tamara, one of three finales reportedly shot for Tempest (1928). Menzies positions the characters so their surroundings influence the emotional temperature of the scene. A line of shadowy witnesses in the foreground adds depth, while the eye is drawn to the distant figures by the sunlight streaming through a church window. What director Sam Taylor added must have been negligible. (MENZIES FAMILY COLLECTION)

As with all of his assignments, Menzies drew heavily from an ever-expanding library of reference books, oversized volumes, rebound in some cases, culled from thrift shops and studio libraries, all lavishly illustrated. The English Interior by Arthur Stratton. In English Homes (three volumes) by Charles Latham. Books on costumes (Robes of Thespis) and furniture. Folk Art of Rural Pennsylvania, Die Alte Schweiz (cities of old Switzerland), Provincial Houses in Spain, Portuguese Architecture. A useful series of books published by Brentano’s included such titles as Picturesque Mexico (1925) and Picturesque Yugo-Slavia (1926).

At the finish of Tempest, John Barrymore, believing it out of all of his pictures “the one thing that is any good at all,” gifted Menzies with “a peculiarly hybrid of artistic junk” for his library. “The books on architecture are in no way a suggestive reflection on your own magnificent craftsmanship,” he said in an accompanying note, “but I thought perhaps you will find in them a possible idea for a semi-detached urinal for Agua Caliente!!”