8

A Few Faintly Repressed Bronx Cheers

In May 1930, United Artists announced that the company would produce between nineteen and twenty-one features at a cost of approximately $17 million, up nearly $2 million from the previous year. It was an ambitious schedule, highlighted by releases from all the major partners, including Chaplin, whose last picture, The Circus, had dominated the 1927–28 season. Menzies, however, never worked for Chaplin, and the other big hit of the upcoming season, Goldwyn’s Whoopie! would be designed by the self-taught Richard Day. Menzies was left with a dreary slate of Schenck productions—DuBarry, Woman of Passion, which would effectively kill Norma Talmadge’s career; The Lottery Bride, a stilted musical; Abraham Lincoln, D. W. Griffith’s first all-talking picture; Forever Yours, an aborted remake of Talmadge’s Secrets with Mary Pickford; Reaching for the Moon, a modern-dress musical for Douglas Fairbanks; and Pickford’s ill-advised remake of another Talmadge success, Kiki.

All carried the distinctive look of a Menzies production, but there was nothing exciting about any of them. Talmadge was beyond caring if she ever made another movie, Pickford was on her way out, as were Fairbanks and Griffith, and The Lottery Bride hastened the bankruptcy of producer Arthur Hammerstein. There were still, however, the shorts, which Menzies unabashedly considered his best work. “They’re artistic triumphs,” he told Florabel Muir of the New York Daily News.

“Did they make any money?” she asked.

“They’re artistic triumphs, I said. Don’t ask me whether they made money. It wasn’t my money I was spending.”

The most elaborate of the shorts, of which there would ultimately be just six, was based on Paul Dukas’ symphonic scherzo The Sorcerer’s Apprentice. For the visualization, Menzies drew from the imagery of the original poem by Goethe, in which an apprentice is left to conjure a helpmate from a wooden broom, thus summoning magical powers he cannot control. Making elaborate use of miniatures, The Wizard’s Apprentice managed a rich look on a pauper’s budget, its effects limited to puppets and double exposures but nevertheless achieving some striking patterns.*1 “William Cameron Menzies and Dr. Hugo Riesenfeld have been producing two-reel, non-talking musical pantomimes from time to time that are so good they usually gather more applause than the so-called features,” Pare Lorentz wrote in Judge. “The best one I have seen is The Sorcerer’s Apprentice [sic]. I advise their owners to give them some money and turn them loose. They probably are the only two men in Hollywood experimenting with movie technique and they know what they are about.”

The shorts seemed to inspire a musicality in Menzies’ work that seeped into his features, most tellingly in the openings he devised and then invariably saw credited to others. Rhythm, he told Muir, was “a goal that you can reach only after the most laborious and painstaking effort.” He illustrated the point with twenty-five drawings that comprised the proposed opening of Reaching for the Moon: The Statue of Liberty. Dissolve to Battery Park. Kids playing. Two men sitting on a park bench. Their feet fill the frame. Newspapers obscure their faces. They discuss the market—what to buy, what to sell. The newspapers drop to reveal the men as two bums. The continuity boards would enable the most inept of directors to follow the pyramiding of the gag, which would invariably be labeled a “directorial touch” in the reviews. “My drawings are copyright,” he said at the time. “They protect me against the danger of anyone coming around later on and claiming my ideas as their own.”

For the beginning of Kiki, Menzies designed a camera crane dubbed “the rotary shot” for the near-circular field of vision it could encompass. The device consisted of a caged camera platform fixed to a perambulator that ran on a rail attached to the ceiling of the stage. Operated by six men, the platform could travel in a straight line or a semicircle, as desired, while moving up or down with the aid of a system of weights and pulleys. Updating the memorable traveling shot from the Talmadge version of the play, the camera opened on a pair of shoes, crossed on a table and tapping to the beat of a rehearsal. Pulling back, the shot revealed an old stagehand caught up in the rhythm while in the process of sharpening a pencil. It continued past other stagehands, posting bills, hammering, sawing, all working in time to the music, eventually catching the image of a gigantic papier-mâché elephant as it danced into view. Backing up still further, the camera took in the full breadth of the chorus line in mid-routine, ending on a pan to an office door.

On the surface, Abraham Lincoln, Griffith’s picture, with its obvious parallels to The Birth of a Nation, offered the greatest opportunity to do something stirring and original. Menzies thought Stephen Vincent Benét’s script “marvelous” but felt it left “great gaps in visualization.” Said Menzies: “We had to build up the idea of Lincoln’s immortality with pictorial effects. Here’s how it was done. We fade in on a log cabin in the wilderness. Then truck up to the door. We see a woman’s face. She’s working around the cabin, says nothing. Then another woman’s face. The first woman says, ‘What are you aimin’ to call him?’ The second woman says, ‘Abraham.’ In the end of the picture, we shoot back to the cabin and hear that one word—Abraham. Then from the cabin to the inscription on the Lincoln memorial in Washington and dissolve to Daniel Chester French’s statue.”

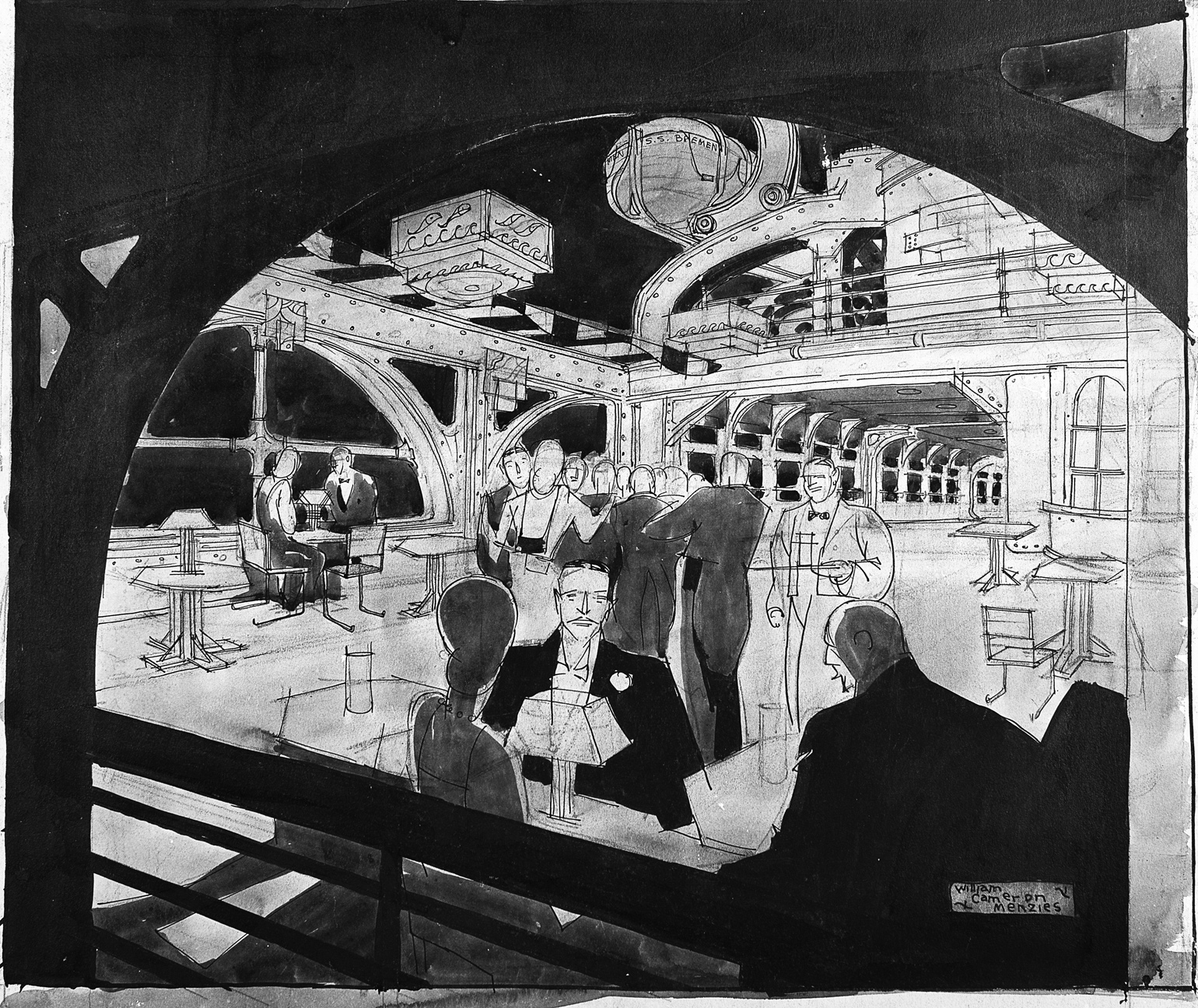

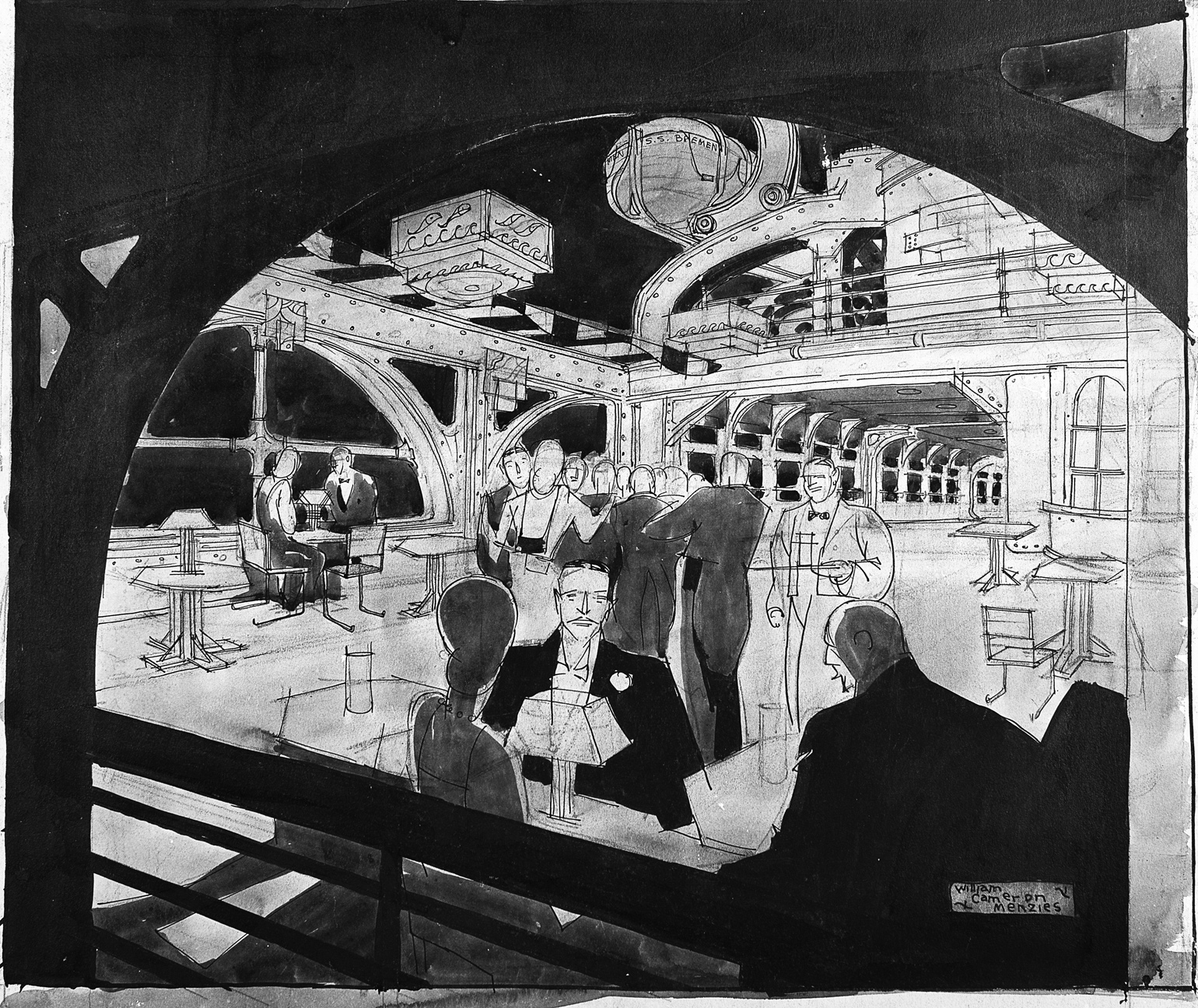

Menzies’ best efforts notwithstanding, Abraham Lincoln was aggressively uncinematic, a theatrical antique within a year or two of its release. “It was straightforwardly shot,” Karl Struss acknowledged. “It was an episodic affair by its nature. There wasn’t much you could do with it.” Griffith himself considered it “all dry history with no thread of romance.” Of the season, Menzies’ most memorable achievement would be the gleaming Art Deco steamship he created for Reaching for the Moon, its entire promenade deck, bridge, and superstructure snugly filling one of only two large soundstages on the UA lot, its interiors occupying the other. Reaching for the Moon took shape in the aftermath of the stock market crash, when Irving Berlin was inspired to create a shipboard romance in which Black Tuesday would be the turning point. The project was announced in January 1930, with Berlin already in the process of writing a script and five songs. In March, singer-actor Regis Toomey was reported as likely for the lead—a Wall Street millionaire who gets wiped out in mid-voyage. By May, however, Toomey was out in favor of Douglas Fairbanks, who needed a picture but couldn’t sing a note.

Berlin’s enthusiasm wavered; he was unhappy being stuck in California, yet musically he felt he was doing some of the best work of his career. (He was particularly proud of a moody waltz that carried the film’s title.) Neither Mammy nor Puttin’ on the Ritz had been of particular importance to him—either personally or professionally. Fairbanks’ participation ensured a generous budget, and Schenck afforded the production every courtesy. But the screenplay wasn’t right, and the size of the undertaking made it an inappropriate choice for John Considine’s debut as director. When, in August, actor-playwright and sometime composer Edmund Goulding replaced Considine, Berlin rejoiced, hailing Goulding as “a genius [who] talks my language.”

The honeymoon was short-lived. Musicals, which, along with stage plays, had been a mainstay of the talking screen, had fallen into disfavor. “The producers looked forward to an era of revues, operettas, musical comedies, and even talked a little of grand opera,” wrote Edwin Schallert in the Los Angeles Times. “Today they have turned thumbs down on even the suggestion of most such ventures. The truth of the matter is that the majority of musical pictures were flops at the box office. It got to such a stage that filmmakers became positively afraid of such product. They retitled follies shows and shelved other productions that relied for their appeal on melody. Even pictures with incidental music were referred to as ‘straight’ comedies or dramas, or else other people were featured beside the singing principals.”

As originally conceived by Menzies, the ocean liner in Reaching for the Moon (1931) was a triumph of spatial arrangement and forced perspective. Considerably modified, the actual set was used to stage the boisterous Irving Berlin number “When the Folks High Up Do the Mean Low-Down” and little else. (MENZIES FAMILY COLLECTION)

Filming began in October with a script credited to playwright—and longtime Ziegfeld associate—William Anthony McGuire. Four songs made the cut, and Berlin, in a letter to a friend, reported that the picture “really looks great.” Goulding, he added, was “doing a great job on the story. The numbers are well placed.” But then something happened to completely change the course of the movie. Likely, that something was The Lottery Bride, Feature’s second film musical, which was an obvious stiff to preview audiences. Goulding, perhaps under pressure, made the decision to rewrite the script, removing all the song numbers and rendering the movie one of those “straight” comedies Schallert had alluded to just a couple of months earlier. According to Maurice Kussell, the choreographer on the picture, Goulding had a “violent disagreement” with Berlin, who walked out on Reaching for the Moon.

The fallout was significant. At a cost of more than $1 million, Reaching for the Moon was a guaranteed money-loser. Overextended, Schenck transferred control of Art Cinema to Sam Goldwyn. Berlin went back to New York, not to return until the making of Top Hat in 1935. Douglas Fairbanks lost interest in moviemaking, and retired for good in 1934. Considine accepted an offer from Winfield Sheehan to join Fox as a producer and, eventually, it was promised, director. Bunny Dull, Schenck’s production manager, followed Considine to Fox as the new unit’s business manager. And, on December 15, 1930, Menzies, having obtained a formal release from Schenck, signed with Fox as well, a move that would finally bring him a chance to direct.

Menzies’ deal with Fox was for one picture at a salary of $7,500. Strictly speaking, his draw of $500 a week represented a $300 pay cut from what he was making with Schenck, but it was an opportunity he had long coveted and a gamble he was willing to take. “Producers are spending plenty of time fussing as to prospective future stars, feature players, etc., and wasting a lot of money, but they are doing very little in the way of scouting for new directorial material,” Harry Modisette observed in a trade paper commentary. “They think nothing of foisting a new face on the public, after having invested several thousand dollars on that particular film, but ask them to give a chance to a fellow who has never directed a picture, but who may have shown his qualifications during a period of years in a thousand ways, and they throw up their hands in horror.”

It was a common practice in the early days of sound to pair even established directors with dialogue men who were usually drawn from the stage. When Lewis Milestone directed All Quiet on the Western Front, he had George Cukor, a veteran of dramatic stock, to handle the actors, many of whom had no theatrical training. When Cukor himself became a director at Paramount, he was teamed with a man experienced in the mechanics of filmmaking, an editor named Cyril Gardner. And so it was that Menzies, who knew as much about the camera as any director working in Hollywood, was given a codirector in the person of an actor named Kenneth MacKenna. It would be MacKenna, thirty-one, who would coach the performers, leaving the camera work and the physical look of the picture to Menzies. “Wise boy, Kenneth, to direct instead of act,” Louella Parsons commented. “I am told he did very well in New York when he produced Windows and What Every Woman Knows. There are plenty of actors, but few directors, and if Mr. MacKenna has a talent in that direction my advice to him is to direct.”

In January, it was announced that Menzies’ first film with MacKenna would be Always Goodbye, the original story of a “female Lothario” by playwright Kate McLaurin. The picture was supposed to showcase the Italian-born actress Elissa Landi, who had just completed her first picture for Fox. There was a general assumption the ethereal Landi was being groomed by production chief Winfield Sheehan to be Fox’s answer to Garbo and Marlene Dietrich—a stretch in that Landi, though beguiling, had none of the smoky mystery that distinguished those actresses. She was, in fact, decidedly at a disadvantage as a man-killer, but her native intelligence—and a set of piercing green eyes—commanded attention. Menzies and MacKenna spent twelve weeks preparing the film, MacKenna exhibiting a flair for literary values that informed his later career as a story editor for M-G-M. The film went into production on March 9 under the title Red-Handed.

There wasn’t much to be done with the picture, and the script, mostly the work of actor-playwright Lynn Starling, wasn’t as cinematic as it was theatrical and witty. Other than a lively jazz party montage at the film’s opening—and some smoothly accomplished tracking shots—the burden of the work fell to MacKenna. Dialogue was staged in long takes with relatively few reaction shots. Filming wrapped on April 3 after twenty-three days before the cameras. The result was a conventional caper picture, scarcely an hour in length. Menzies agreed to a contract modification that gave MacKenna equal billing (“A William C. Menzies and Kenneth MacKenna Production”) and Fox studio superintendent Sol Wurtzel picked up his option on April 18. Three weeks later, with the film cut and awaiting release, the studio tore up Menzies’ old contract and awarded him a new three-picture deal at $10,000 per.

Always Goodbye opened at New York’s Roxy Theatre on May 22, 1931. The notices were polite, the attendance unexceptional. Judging it “better than average,” Irene Thirer of the Daily News was the only major critic to highlight the debut team of Menzies and MacKenna. “Give them a hand,” she wrote at the head of her review. “The Roxy’s film moves smoothly, interestingly, and tastefully for three-quarters of an hour. It doesn’t become obvious until the first half has been unreeled. Then its hold on you weakens considerably and you’re sure you know exactly how it’s going to conclude. And you’re right!”

Two Menzies-MacKenna collaborations were announced for the 1931–32 season, both again featuring Elissa Landi and sporting the underdeveloped titles Cheating and In Her Arms. (“Oriental pride yields to Parisian kisses in a duel of male might and female charm” blared the copy.) Ultimately, the studio had a property better suited to Menzies’ sensibilities in The Spider, a “play of the varieties” that had notched more than three hundred performances on Broadway. “The Spider,” Menzies later observed, “was novel inasmuch as all the happenings occurred on one set, a theatre auditorium, stage, backstage, and dressing rooms.” For it, Menzies would be working again with unit art director Gordon Wiles, who had been part of his team at United Artists. Wiles, in turn, would bring forth the interiors of an entire vaudeville theater in the impressionistic strokes Menzies envisioned, eschewing the ornate detailing that had once typified the house style at UA. Actor-playwright Barry Conners, an ex-vaudevillian, was brought onto the project to draft a final shooting script. Menzies sat with him and, working from continuity sketches, meticulously detailed the entire visual structure of the film, shot by shot. When filming commenced on June 11, 1931, the picture had been prepared to such an extraordinary degree that a three-week schedule was not deemed unreasonable.

Edmund Lowe, Howard Phillips, and Lois Moran in the backstage thriller The Spider (1931) (AUTHOR’S COLLECTION)

Starring as master magician Chatrand the Great, a role created in New York by John Halliday, would be Edmund Lowe, an efficient if somewhat colorless actor who had been an attraction for Fox since his turn as Sergeant Quirt in What Price Glory? Paired with Lowe as the niece of the murdered man would be Lois Moran, soon to conquer Broadway in the Gershwin musicals Of Thee I Sing and Let ’Em Eat Cake. Imposed on the production as a member of the audience would be El Brendel, the ubiquitous faux Swede who was somebody’s idea of comic relief.

Menzies took particular relish in the shooting of Chatrand’s stage effects, which included the severing of a human head and the film’s climactic séance, during which the shade of the dead man is summoned from the spirit world and the killer with the spider ring is revealed to the audience. Menzies tended to refer to these bits as “devices” as one might refer to a gadget designed to do a specific thing. “It’s the way we fool the camera, not the audience,” he explained. “The camera is the real heavy because it sees what we don’t want it to see and it sometimes picks up what we don’t want it to. [In] The Spider … I wanted to use that gag about the magician’s cutting off the woman’s head. Remember that old trick? Well, I wanted to do it without cutting, shooting it in a single sequence and keeping the camera moving for the entire scene. Of course, we could have cut it together, but it was more fun to do it the other way just for our own satisfaction.”

Throughout, the film was taut and elegantly composed, as handsome and careful a job of staging as anything Fox had managed that season. When Winnie Sheehan screened The Spider toward the end of July, he sent Menzies a congratulatory note: “I consider it a ‘corking’ good entertainment, an excellent mystery melodrama, and everyone connected with the picture deserves credit, to which I herewith subscribe.”

Sheehan wasn’t the only one taken with The Spider. The Hollywood Spectator extravagantly praised the work of Edmund Lowe, Lois Moran, Menzies, and Kenneth MacKenna, despairing only at the presence of El Brendel in the cast. “The sustained sequences wherein Lowe and Howard Phillips—a very personable young gentleman, by way of interpolation—try to locate the murderer who is seated in the audience before them, are tense and gripping when they very well might have been boring and ridiculous. The lighting effects and camera technic displayed in these scenes are striking.” The New York notices were somewhat more reserved, hampered as they were by memories of Albert Lewis’ original staging of the play, where the entire audience effectively became part of the cast. All lauded the film’s breakneck pacing, and most all appreciated the intensity of Lowe’s hammy performance as Chatrand, a job that reportedly left the actor on the verge of a nervous breakdown. Again, it fell to Pare Lorentz to highlight Menzies’ contributions to the picture, which were considerable and obvious to anyone who was paying attention.

“It is entertaining, amusing, well-knit, and, above all, as beautiful to see as Karamazov, Sous Les Toits, or any foreign picture we have seen,” Lorentz said of The Spider. “Fortunately, the semi-supernatural plot allowed Menzies to indulge himself in simple, austere sets—huge Gothic arches, dimly lighted, with his characters in black silhouetted against them—sets that heightened the atmosphere and aided the plot. Besides the architecture, The Spider is worth seeing because of its good pace, its easy humor, and its excellent cast. I hope Mr. Menzies gets a crack at another manuscript soon. He is one of the few movie-minded men in all Hollywood.”

The Spider drew well in places like Minneapolis, where the trades credited word of mouth and “fastidious critics” for the crowds at the Lyric Theatre. At a cost of $311,517, the film went on to worldwide rentals of $519,137, showing a modest profit of $16,052. Following the disappointment of Always Goodbye, which drew respectable notices but posted a loss of nearly $70,000, Menzies and MacKenna were finally proving their directorial worth to the management at Fox Film. Sheehan approved separate pictures for both men, assigning MacKenna a racy comedy called Good Sport and Menzies another thriller with the working title of Circumstance.

Originally published in Great Britain as The Devil’s Triangle, Circumstance was the work of the prolific English novelist Andrew Soutar, whose particular bent was mystery and spiritualism. Soutar’s book was snapped up while still in manuscript, and treatments had already been developed by Kathryn Scola, Doris Malloy, and, of late, the redoubtable Guy Bolton, who was working through a term contract he seemed to regret having signed. When Menzies came onto the project, he took Bolton’s September 2 treatment, written in the traditional style of a short story, and recast it as a sixty-nine-page screenplay with an emphasis on action and imagery over dialogue. He broke it down into individual shots and played a key reception sequence as a series of quick lap dissolves. With the filmic structure sketched in, he was given the okay to go to full script with playwright Edith Ellis supplying the dialogue. Menzies’ old friend Wallace Smith was subsequently brought in for a rewrite, charged with getting away from the director’s fussy shot-specific format. A second draft incorporated yet another set of shot specifications, Menzies and Smith collaborating in much the same way they had in their days together with Schenck at UA.

Production began on October 26, 1931, with Broadway’s Violet Heming making her talking feature debut. The English-born Heming, thirty-six, had been signed by Winfield Sheehan during one of his quick trips east, her latest show, Divorce Me, Dear, having closed after just six performances. Known for her way with light comedy, Heming understandably felt ill-served by Circumstance, in which she was required to play a Russian-born heroine who finds herself wed to a madman. Menzies could be of little help to her, and she played the part with an air of resignation, making no attempt whatsoever to affect an accent. As Capristi, her demented husband, Alexander Kirkland was allowed to run off with the picture, leaving Heming to play most of her scenes opposite Fox contract player Ralph Bellamy (who was nine years her junior).

Menzies kept the film on schedule, devoting considerable attention to Capristi’s escape from an English asylum, a bravura piece of Expressionist filmmaking that would come to be regarded as the picture’s best sequence. With Kirkland chewing the scenery and Heming giving a dispirited, off-kilter performance, Circumstance failed to catch fire dramatically. The rushes weren’t playing, and whatever suspense Menzies managed to kindle was more the result of design and camera technique than genuine storytelling prowess. When the picture wrapped on November 18, there was a sense of its having missed its mark, but nobody seemed to know quite what to do about it. Under the title Almost Married, it was put before a raucous preview audience on the evening of December 3. The next morning, a devastating account of the event appeared in The Hollywood Reporter under the headline “ ‘ALMOST MARRIED’ CAN’T MAKE GRADE.”

“Although the title suggests a sophisticated comedy drama,” the unsigned notice began,

Almost Married is an out-and-out melodrama, with a madman, a harassed heroine, and shadows on the wall. It is so badly done, unimaginatively directed and indifferently acted, that the preview audience last night was openly derisive in spots where they should have been swooning with fright. Not only is the story difficult to follow, jumping as it does from Paris to Russia to London before it finally gets settled, but the director depends for his effects upon numerous closeups of a madman’s glaring eyes and the above-mentioned shadows on the wall whenever things seem to be slowing down.… The only commendable feature of the production is the photography.

James B. M. Fisher of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America (MPPDA) witnessed the preview. “While it contains nothing contrary to the Code,” he advised in a résumé, “it is another ‘gruesome’ picture which falls in the class with Dracula, Frankenstein, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, and Freaks. Maybe we are starting a style. We would be pleased to have from New York any advice that can be given to help us to come to conclusions concerning it.” The MPPDA’s Jason Joy wrote his boss, morality czar Will Hays, the next day: “Is this the beginning of a cycle that ought to be retarded or killed?”

Fox, meanwhile, was in poor shape, with losses mounting and its management in disarray. Heads began to roll with the firing of longtime production manager Theodore Butcher. “This is looked upon as the first in a series of changes among the executives of this company,” The Reporter noted. “Dismissals, it is understood, will range from the highest to the lowest, no one being too small to be overlooked nor too great to be exempt.” Among the first to be sacked were director Allan Dwan, producer-songwriter Buddy DeSylva, and William “Billy” Sistrom—the producer of Almost Married.

The studio held firm to a January 17 release date as New York production executive Richard Rowland commissioned a new treatment incorporating more of Guy Bolton’s material. But the Fox lot was crawling with auditors, Chase Bank representatives seeking to strictly limit Winfield Sheehan’s influence at a time of fiscal crisis. New people were brought in for budgeting and scheduling, and Keith Weeks, the former Prohibition agent who was Sheehan’s handpicked studio manager, was given fifteen minutes to clear out of his office. Harley Clarke, the interim president of Fox, had been removed—sent back to Chicago by the same banking interests who had put him there in the first place—and replaced with Edward R. Tinker, board chairman of Chase National, a career banker who freely admitted he knew absolutely nothing about running a studio. On January 7, 1932, word came that Sheehan had suffered a nervous breakdown—an “authentic” one, the trade press reported—brought on, it was construed, by the systematic stripping of his studio authority. While he was reportedly recuperating at a sanitarium near San Francisco, responsibility for the balance of the Fox season fell to Sol Wurtzel, who was charged with bringing the average cost of a Fox feature down to an industry-wide target of $200,000.

Menzies could do nothing other than wait it out, not knowing how extensive the changes to Almost Married would be, nor whether he would be permitted to remain on the picture. In February, Bolton suggested a new opening, beginning the convoluted story in Russia instead of Paris and dispensing with Anita’s marriage to Capristi with a flashback. Bolton proceeded to incorporate a number of revisions and clarifications into Wallace Smith’s October 23 script, a version finalized on March 17 after Menzies had once again inserted his visual notations. In addressing the problem of the actors’ performances, particularly Violet Heming’s, Wurtzel assigned the Paris-born stage director Marcel Varnel to work alongside Menzies in much the same capacity as had Kenneth MacKenna. By the time retakes were completed in early April, the film’s cost had swelled to $267,418 while its running time had shrunk to a mere fifty-one minutes. On April 21, an MPPDA résumé indicated that Almost Married again had been viewed, this time in a projection room at Fox. “A number of changes have been made to the picture, including the transportation of several foreign sequences and a new ending. It is our opinion that the revised version is satisfactory [to the Code].” A separate document described the film as “rather well produced—but not outstanding.”

The debacle of Almost Married effectively ended Menzies’ career as a solo director at Fox, even as the studio proved willing to keep him on. Prior to his illness, Sheehan had created several new directing teams in response to John Ford’s departure over a salary dispute. Initially, Marcel Varnel had been joined with assistant director R. L. “Lefty” Hough, and together the two men had filmed Silent Witness, a small but unusually compelling courtroom drama. Varnel, thirty-nine, could handle actors effectively but had little knowledge of film technique, a circumstance that seemingly made him an ideal fit for Bill Menzies.

Violet Heming and Herbert Mundin in a chiaroscuro moment from Almost Married (1931), Menzies’ troubled debut as a solo director (AUTHOR’S COLLECTION)

Menzies knew from the beginning that making the leap from the drafting table to the stage floor would be an uphill battle, as no art director had managed the feat since the coming of sound.*2 Fortunately, the failure of Almost Married was somewhat mitigated by the release of The Spider—and both events were concurrent with the debut of a syndicated radio serial called Chandu the Magician. Competition for the new property, being heard on some forty stations, came with the assumption of a built-in audience, and the purchase price of $40,000 was steep. (Fox, by comparison, had paid $27,500 for the rights to The Spider, which had proven its drawing power on Broadway.) Edmund Lowe was promptly announced as its star, and assigned to direct was actor-director John Francis Dillon. The deal for Chandu was finalized on March 29, 1932, as the retakes for Almost Married were being made. Barry Conners and Philip Klein, the prolific team responsible for The Spider, were put to work on an adaptation, and the combination of Menzies and Varnel soon supplanted Dillon as directors. Fox Film Corporation formally exercised Menzies’ first-year option on May 9; the same day, Irene Ware, a slender redhead, late of Earl Carroll’s Vanities, arrived in Los Angeles to begin work as a Fox contract player.

While The Spider incorporated brief episodes of mysticism, wispy strands of ectoplasm conjuring the spirit world and images of the dead, the picture was essentially an imaginatively filmed whodunit set within the confines of a metropolitan vaudeville house. And for all the earnestness of Edmund Lowe’s one-note performance, it was directed with a wink and a nod, its tricks wholly and good-naturedly mechanical. Chandu the Magician was something else altogether, an effects-laden adventure in North Africa in which the title character was a genuine yogi with occult powers and an adversary bent on world domination. The story had romance and comedy and a scope approaching The Thief of Bagdad, albeit on roughly one fifth the budget. By early June, Menzies was puzzling out the story’s visuals and leaving the casting decisions, for the most part, to his colleague Varnel.

Menzies, meanwhile, huddled with cameraman James Wong Howe, who had shot The Spider and found the new assignment “much more rewarding” than the Fox programmers to which he was typically assigned. For the Indian rope trick, they would fit a boy with a harness and elevate him with a wire and overhead gear. A full shot of the illusion would be made by staff effects specialist Ralph Hammeras using the Dunning Process to marry the foreground action with a reverse plate of the temple background. The coals for a fire-walking stunt would be made of broken glass, lit from underneath and rigged for steam and lycopodium flames. The projection of a death ray would be handled by optical effects wizard Fred Sersen “by building a beam against black velvet and drawing a card across the beam exposing it at whatever speed is decided and then doubling this effect on the screen as shot on the set.” All stunts, effects, and process shots for Chandu the Magician were agreed to and finalized on June 23, 1932.

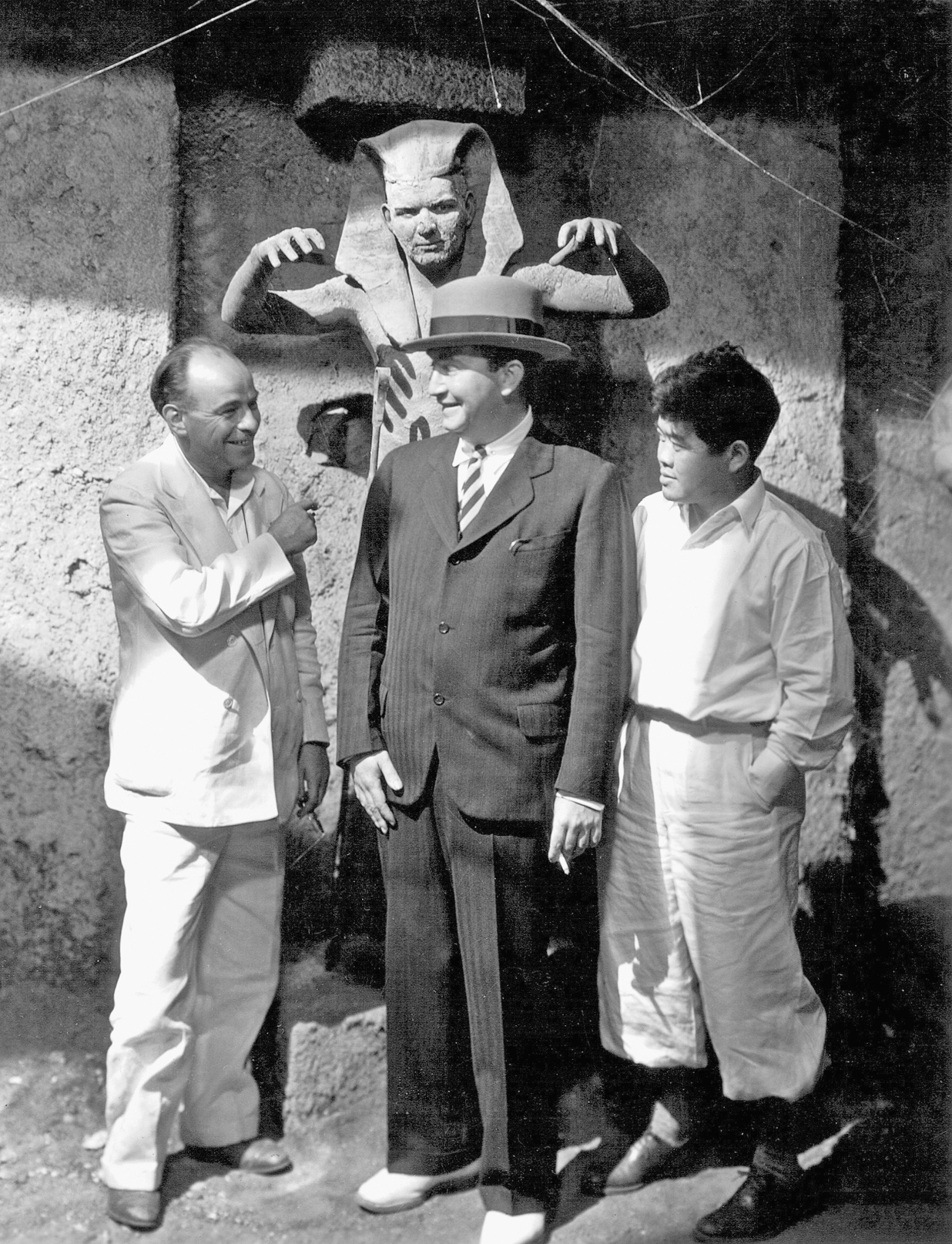

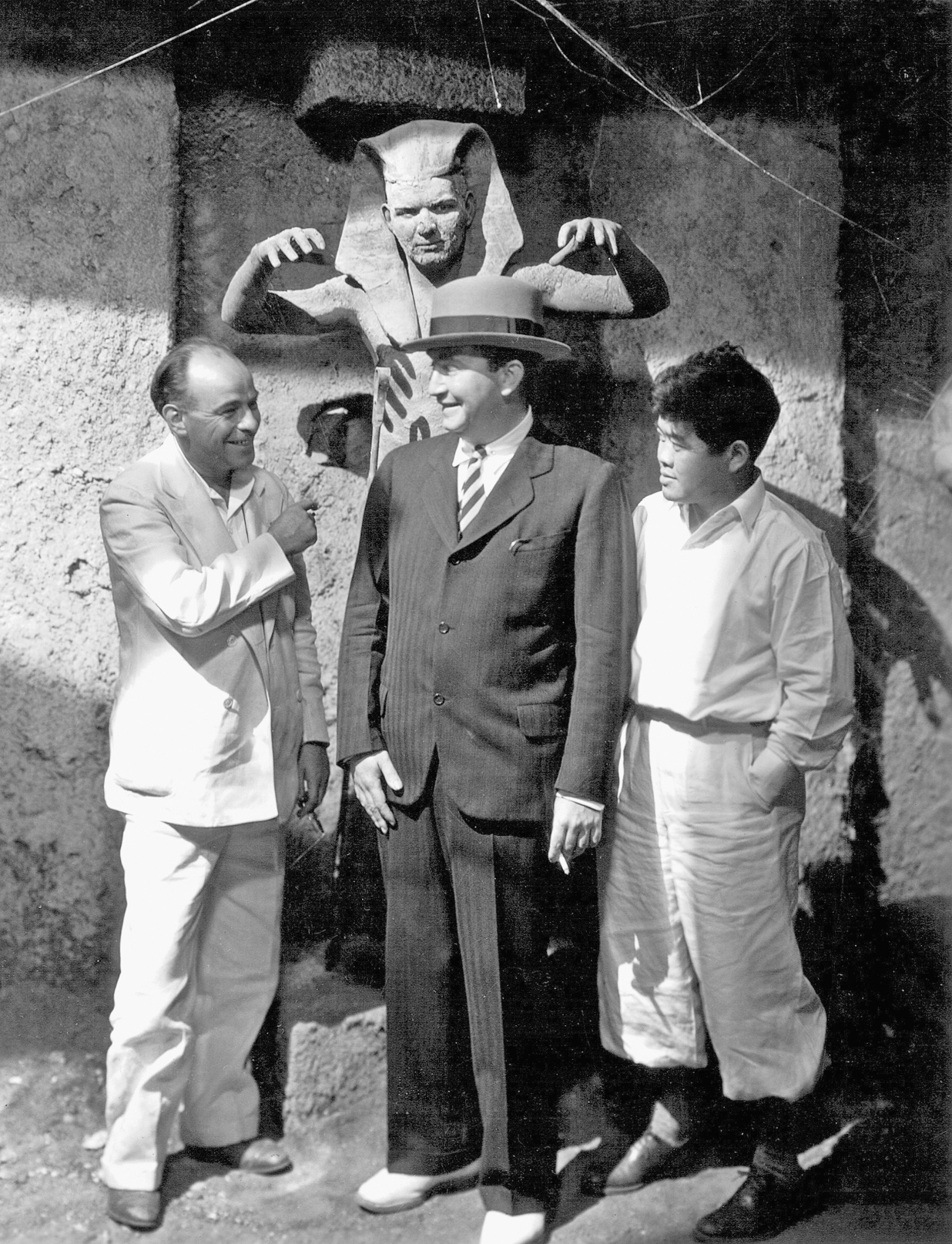

The 116-page shooting final, dated July 7, 1932, incorporated visual continuity to an unusual degree, expressing graphic values and technical details alongside the traditional elements of dialogue and action. It wasn’t ideal; Menzies preferred working off his continuity boards, but the Chandu script was the closest he had yet come to one fully integrated document for the making of a movie. With Lowe as Chandu and the promising but inexperienced Irene Ware as Nadji, the picture demanded a truly “evil and menacing” Roxor, the Egyptian madman in pursuit of a death ray. Actor Bela Lugosi, Universal’s Dracula of the previous year, had done several pictures at Fox as a freelancer and was secured for the part on a two-week guarantee. Rounding out the cast were veteran character actor Henry B. Walthall and Fox contract players Herbert Mundin, Weldon Heyburn, and June Vlasek. Filming began on July 11, 1932, and continued into early August.

Composition as storytelling: Bela Lugosi holds the foreground in this still posed on the set of Chandu the Magician (1932). Edmund Lowe and Irene Ware occupy the middle distance, their path of escape diminishing perilously behind them.

(AUTHOR’S COLLECTION)

The creative team behind Chandu the Magician: Co-director Marcel Varnel, Menzies, and cinematographer James Wong Howe. Varnel completed just one more picture for Fox before relocating to England, where he spent the rest of his career directing the likes of George Formby and Will Hay. (ACADEMY OF MOTION PICTURE ARTS AND SCIENCES)

For Menzies, the world of Chandu became a wizard’s catalogue of split screens and double exposures, miniatures, rear projections, and Tesla coils. Some opticals limited his compositions, while others proved unequal to the film’s limited budget. Throughout, a mood of ancient mysticism pervaded, enveloping the performances, lending tone and texture to readings where otherwise there would have been none. (“There’s no question that when actors walk into a set of any kind it will affect their performance,” he once said.) Seemingly immune to such augmentation, Bela Lugosi proved the lone standout, as potent as any camera trick, his thick Hungarian accent—he hadn’t yet mastered English—giving his Roxor a Homeric quality, his orgasmic rant, over visions of the world’s great cities falling to his death ray (“All that lives shall know me as master and tremble at my word!”) as Shakespearean as anything in the popular cinema of the day.

Immersed in the production of Chandu, Menzies was able to ignore the inglorious release of Almost Married, which was exiled to Brooklyn for the week of July 22. Mercifully, the New York dailies failed to take notice, leaving its critical drubbing largely to the trades. “Beyond the paucity of screen names,” went the Variety review, “the film struggles along with a pretty much overdrawn and implausible story. Some of it is quite well handled, and there is sufficient action, but even within the confines of 50 minutes a good deal of the film is slow and draggy.… It’s pretty complicated, and William Cameron Menzies, turning in his first directorial job, couldn’t seem to avoid being buried under the various tangents.” The film’s November opening in Los Angeles went similarly unacknowledged and was held to the outskirts of the market, playing double bills strictly in neighborhood houses. Worldwide revenues for Almost Married were a dismal $228,271, resulting in an eventual loss of nearly $140,000.

The best news for Menzies that summer was Chandu, its potential seemingly limitless as it rolled its way toward an aggressive release date of September 18. Due to effects shots requiring lab and optical work, the movie wasn’t ready for preview until September 2, nearly a month after production had closed.

The Hollywood Reporter:

There are several million kids, more or less, waiting for this picture all over the United States, just as they have been waiting at 7:15, five evenings a week, during the last year for the latest episode of Chandu the Magician over the air. Judging from the reception two or three hundred youngsters gave the production last night, even though their elders smiled indulgently at Eddie Lowe’s feats of magic, this picture will spread a new crop of black ink on the Fox books. After the exhibitors have played this one, they’ll probably start wiring their local Fox exchange to find out when they can book The Further Adventures of Chandu the Magician.

Chapin Hall of The New York Times hailed the picture as the first of potentially many radio properties to make it to the screen.

The piece has been skillfully handled and, with the story and the setting, used the camera tricks [to] appear to be genuine magic. The screen apparently has not dared use these tricks since the earlier days, when men jumped out of rivers onto bridges for comedy reasons. But Chandu walks through walls, escapes from a coffin at the bottom of the Nile, walks through fire without the slightest discomfort, and does all the glorious things expected of such a hero. An audience of reputedly cynical newspaper fellows hissed the villain and applauded the rescue of the heroine with a sincerity which was remarkable.

Sol Wurtzel authorized a full-page ad in the September 13 issue of Variety. Under the headline “PACKED WITH EXPLOITATION MAGIC,” the studio heralded the sixty-two stations then carrying the radio Chandu and promised local tie-ups with Beech-Nut distributors and White King soap—companies that “spent a fortune in car card and billboard advertising of the broadcast.”

It was hard not to buy into the notion that Fox had a monster hit at the ready, and plans were to open the picture in Los Angeles ahead of its New York premiere. Advance press leaned heavily on the radio connection, and early reviews called to mind the same early chapter plays that Chapin Hall remembered so fondly. “As conceived by Fox Films, Chandu comes pretty close to being the ideal cameraman’s nightmare,” Philip K. Scheuer wrote in the Los Angeles Times. “So jauntily incredible are its sequences, so pell-mell do they come tumbling forth, that one is all but convinced that he has walked in upon a revival of a 1915 movie. There are only those voices, those unearthly sound effects, to persuade him otherwise. Those, and a really ingenious use of the cinematograph.”

Business skewed more heavily to kids than initially anticipated—not a good sign—and the tie-ins with the radio serial reinforced the idea that grown-ups should stay away. Rob Wagner, who, in his magazine Rob Wagner’s Script, presumed to speak for the adults in the audience, defined the recipe:

Take a bunch of turbans, several crystal balls, a nest of snakes, eight Egyptian mummies, a bag of toads, the Hindu rope trick, and some esoteric Yogi hokum. Add to these good old props of the Mystic East a lot of faked experimental machines and gadgets from the Western Electric Company’s laboratories, and the phony science page of the Examiner’s Sunday supplement. Stir in a Chinese cameraman, Bela Lugosi, and Eddie Lowe’s hypnotic eyes. Then let thirty-two screen-credited authors, laughing in their sleeves at the alleged moronic mentalities of American audiences, stir to the consistency of applesauce. Serve to the accompaniment of screech horns and tom-toms in the key of Asia minor. This is the dish Mr. Fox F. Corp. served at the Beverly Theatre, hoping to mystify and frighten the villagers. But all he got for his and the audience’s pains were a few faintly repressed Bronx cheers from the adults, laughter from the adulteresses, and raspberries from the kids.

Chandu the Magician was hardly a disaster. Worldwide rentals totaled nearly $500,000, but it never took off in the way the studio had hoped, inspiring awestruck word of mouth and repeat business from followers of the daily radio serial. At a final cost of $349,456, Chandu fell short of break-even by more than $50,000, bringing Menzies’ record of losses as a director at Fox to nearly a quarter million dollars.

*1 Walt Disney, who was to begin releasing his cartoons through United Artists in 1932, may have been inspired by the Riesenfeld-Menzies shorts to embark on the animated feature Fantasia in 1938. Menzies considered Disney the “greatest genius” in Hollywood. “Why? Because he alone has caught the real meaning of rhythm on the screen. I hear a lot of directors and supervisors talking about rhythm, but it’s only talk. They don’t know what it is nor how to get it. Disney does, and my hat is off to him.”

*2 In silent days, Hugo Ballin (Jane Eyre, Vanity Fair) and Ferdinand Pinney Earle (A Lover’s Oath aka The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam) became directors, though Earle had to finance his own picture. In 1934, Cedric Gibbons would become the credited director on Tarzan and His Mate.