10

The Shape of Things to Come

Exactly how William Cameron Menzies came to the attention of Alexander Korda isn’t known, but it’s easy to imagine an initial word coming from any of several Americans then working for the man who had single-handedly made the British film a viable international commodity. There was, for example, cinematographer Harold Rosson, who was in London shooting The Scarlet Pimpernel for Korda. And the visual effects wizard Ned Mann, who had first worked with Menzies on The Thief of Bagdad. And then there was Douglas Fairbanks himself, who was appearing for Korda in what would be his final film, The Private Life of Don Juan. Knowing that Korda was intent on making The Shape of Things to Come, which would depict the future as imagined by H. G. Wells, Fairbanks may well have suggested the artist who had so successfully envisioned Bagdad as the perfect man to bring Wells’ Everytown to the screen.

Menzies left Los Angeles via the Chief on Sunday, August 12, 1934, with passage booked on the Ile de France for the following Saturday. It took two days to get to Chicago by train. “Stopped in Newton and was interviewed by a lady from the local paper,” he wrote Mignon. “It’s too bad my credits lately aren’t more imposing.” On the trip over, there were about 180 passengers on a ship designed to carry 600. On board were director Al Santell and his wife, Jack Alicoate of The Film Daily, director William Beaudine and his wife, and Lady Peel (the comedienne Beatrice Lillie). Menzies’ commitment to Korda was to keep him in London until at least January, but at the time of his departure there was nothing more from Wells than the original book, a didactic work of prophecy published in 1933, and a treatment bearing the singular title Whither Mankind? A Film of the Future.

Menzies was anticipating trouble with his labor permit, but there was none. He settled into a flat in Albemarle Street, Piccadilly, where the rent was mercifully cheap—five guineas a week (about US $25, including service). “It looks as if at worst it’s co-direction with Korda and the biggest picture in English history, very difficult but right up my alley.… I feel I’m going to be a hit here, and at least for the moment I’m simply insane for the place. The people are lovely. Maybe it will pall, but I doubt it. London is still full of hookers and pansies, but everyone is so polite and friendly.”

There were friends to see: Laurence and Rosalind Irving; the American art director Jack Okey, who had been brought over by Korda to design a new studio complex; Hal Rosson; Paul and Molly Perez. One weekend, Menzies blithely hired a taxi to drive him to Aberfeldy, a distance of some 450 miles. “Things move terribly slowly here and I get very upset worrying about it,” he wrote, “but when I spoke of it to Korda, he said he had nearly gone crazy when he first came over, but after a while you get to expect it.” On a night in October, he dined at Korda’s with H. G. Wells, who held sway over the project to such an extent he spoke frequently of it as “my film.” A portly little man with an unnaturally high-pitched voice, Wells was engaged in the prentice effort of revising his initial treatment, and Menzies felt their exchange that evening “accomplished a lot.” Wells followed up with a handwritten note: “The film is an H G Wells film & your highest & best is needed for the complete realization of my treatment. Bless you.”

Menzies responded in the only way he could, sketching ideas based on the fragments afforded him, then taking them round to Wells’ flat at Chiltern Court, where they would be summarily rejected or returned for further refinement. “I am still running back and forth to Wells’ and still seem to retain my standing,” he reported in early November. “I have seen very little of Korda lately. Must get over to the other studio and see him this week.” The place at Albemarle was dark and depressing, and in November Menzies took a new flat, light and cheerful, at Marble Arch, where the surrounding streets reminded him of New Haven. The change of scenery had only a momentary effect on his mood swings though, and within days he was despairing again of ever getting the picture into production. “I feel very low today,” he admitted in a letter to Mignon on the 23rd of November. “I suppose from the cold, but I’m not very optimistic about conditions for picture making here and, sub rosa, Korda is very nice but very changeable. It’s too bad movies are such a worry, because I could certainly enjoy life if it wasn’t for the ever-present miserable worry about making money.”

Korda was incrementally sending his production personnel to the United States to keep abreast of the “latest movements and methods of film production,” leaving the impression he wouldn’t be needing his entire staff until the anticipated completion of the new studio in April. Laurence Irving, meanwhile, felt it was the designs Menzies was contriving of a collapsed civilization—and the news from Germany that seemed so much like a prelude—that drove him to seek the solace of the bottle. “After dining with us one evening, he had found release from his tensions to such an extent that I felt I should see him safely to bed at Mount Royal, a vast apartment hotel building. He had forgotten the number of his room. So, in close embrace, we explored one tunnel-like floor after another, as I propped him up at the end of each corridor and sought whatever number he was inspired to suggest. After what seemed hours of trial and error and several altercations with angry residents roused from sleep, I left him safely bestowed in his cell-like quarters.”

Wells acknowledged the collective help of Korda, Menzies, and the Hungarian playwright Lajos Bíró (who essentially functioned as an uncredited scenarist) in developing the treatment from which the film would be made. “They were greatly excited by the general conception,” he wrote, “but they found the draft quite impracticable for production. A second treatment was then written. This, with various modifications, was made into a scenario of the old type. This scenario again was set aside for a second version, and this again was revised and put back into the form of [a] treatment.”

The design of the picture proved as much a challenge as its screenplay. Alexander Korda’s youngest brother, Vincent, would create the settings for the present-day sequences and for the scenes of desolation after decades of war. The rebuilding of Everytown, however, and the views of the city one hundred years hence would require the eye of a true visionary. At various points, futurist painter Fernand Léger, the urbanist architect Le Corbusier, and abstract photographer László Moholy-Nagy were consulted. None proved up to the challenge—Le Corbusier, after reading Wells’ treatment, declined to become involved—and so, as work moved forward, Korda, in consultation with Menzies and Ned Mann, derived much of the film’s futuristic look from an array of published sources, beginning with the descriptions Wells himself had provided.*1

Vincent’s son, Michael, could remember his father “busily ransacking the libraries for avant-garde furniture designs, architectural fantasies, helicopters and autogyros, monorails and electric bubble cars, television sets and space vehicles. The nursery at Hampstead became a repository for his rejected design models, and while other children were playing with trains and toy soldiers, I was playing with rocket ships, ray guns, and flying wings.”

Gradually, it became clear to Menzies that Alexander Korda expected him to direct the picture entirely by himself. Ned Mann described a working relationship far more collaborative than what he usually saw in Hollywood: “Vincent Korda, the art director, outlined his conception of the ideas contained in H. G. Wells’ script. I added my suggestions to those of William Cameron Menzies, the director, and Georges Périnal, in charge of the cameras, and others. And when all points of view had been considered I was able to decide how the desired effects were to be produced.” André de Toth, who would later work with the Kordas, recalled Vincent as “the most unassuming human being I met. He would put his rumpled hat on, a cord to tie up his pants. He was a happy man. He was a true artist. He really didn’t belong to the picture business.”

Menzies bonded with Vincent Korda in a way he couldn’t with Alex, the master salesman who brought all the sparkle to the trio of Hungarian brothers (director Zoltan Korda being the third member of the triumvirate). “I have gotten to be great friends with Vincent Korda,” Menzies wrote in February 1935, “which is a good break for me.” The “trick stuff” (as Menzies put it) was already under way at Consolidated Studios, Boreham Wood, but casting was still to be settled, the only name mentioned thus far being Robert Donat, who had drawn notice for his work in The Count of Monte Cristo. Wells, noted Menzies, seemed to like the early effects footage, although “it’s always tough for laymen to understand uncut stuff.”

By then, Menzies had settled into a thoroughly cosmopolitan lifestyle, acquiring a car, a new wardrobe, and a mistress. “I’m sorry our pals can’t see me in my trick English clothes,” he said in one letter. “I resemble a well-dressed prize fighter with the very square shoulders and small hips. My suits came out very well too. The suits cost about $65 apiece and the shirts about $7 and [are] the best in London.” Yet the picture was going so slowly by Hollywood standards that insecurity nearly consumed him. “I expect Korda to blow up any day and fire us all, but we are doing all we can. The expense, of course, is terrible. At least I would get home, but I’m afraid if it did blow up it wouldn’t do me any good. I have worried about the thing ever since I got off the boat, which is one of the things that has made me unhappy in England.”

On the first of March, with Wells on his way to New York, Menzies recounted “a very pleasant interview” with Korda that helped ease his anxieties. He was set to move to Worton Hall, Isleworth, to begin shooting, but there were problems with the costumes—specified, detailed, and often rejected by Wells. “I miss you terribly,” he wrote Mignon, “and if it wasn’t that I thought this picture will make me, I’d have gotten myself fired a long time ago. I still think it will be a sensational picture if we ever get it done, and Korda is undoubtedly the whitest man I have ever worked for. I can do practically anything I want.” Two weeks later, he felt the return of “the old Hollywood strain, fluttering guts and everything, as I am trying to put over something new, and you know how I worry. I did a sequence in drawings that Korda liked immensely, and am shooting it next week. It’s just with extras and atmosphere, but it’s the kind of thing I do best.”

Story changes were proposed, but Wells, upon his return, would concede nothing easily, and progress, complicated by financing problems, came at a snail’s pace. By April Menzies was “absolutely concentrated” on making Whither Mankind? a great picture, the kind of picture that would secure his future and that of his family. “This is the one big thing in my life now, and I think the results will warrant it. I have a tremendous advantage over here in my general knowledge of pictures, as I can do most of the things myself. My sets, my lighting, compositions, continuity, etc.” Yet he dreaded getting into the dialogue scenes, not only because of his discomfort around actors, but also because of old Wells, who was driving director Lothar Mendes mad on a concurrently shooting picture, The Man Who Could Work Miracles. In May, the company traveled to Blaina, South Wales, to shoot battle footage for which two hundred unemployed miners were issued uniforms and dummy rifles and arranged according to Menzies’ continuity sketches. On June 7, fierce winds laid waste to the Everytown set, which was under construction on what would become the studio backlot at Denham. A painter was killed, and five other workers were injured in the collapse.

A cast was gradually assembled, beginning with Raymond Massey, the Canadian-born actor who had been a memorable Chauvelin in Korda’s The Scarlet Pimpernel. “I had read Wells’ novel,” he recounted, “fascinated by its humor and the earthy humanity of its characters.… But when I saw Wells’ script I was appalled. Every trace of wit, humor, and emotion, everything which had made the novel so enthralling, had been cut and replaced with large gobs of socialist theory which might have been lifted from a Sidney Webb tract. Although Wells often declared he was not a teacher or a political theorist, this was exactly what he had become.”

For the part of the dictatorial Boss, who continues to wage war amid the wreckage of an Everytown bereft of resources, Korda selected Ralph Richardson, relatively new to films but soon to become a genuine star of the West End. For his wily consort Roxana, Korda cast London Films contract player Margaretta Scott, who remembered Menzies as “a delightful person to be with and frightfully good.”

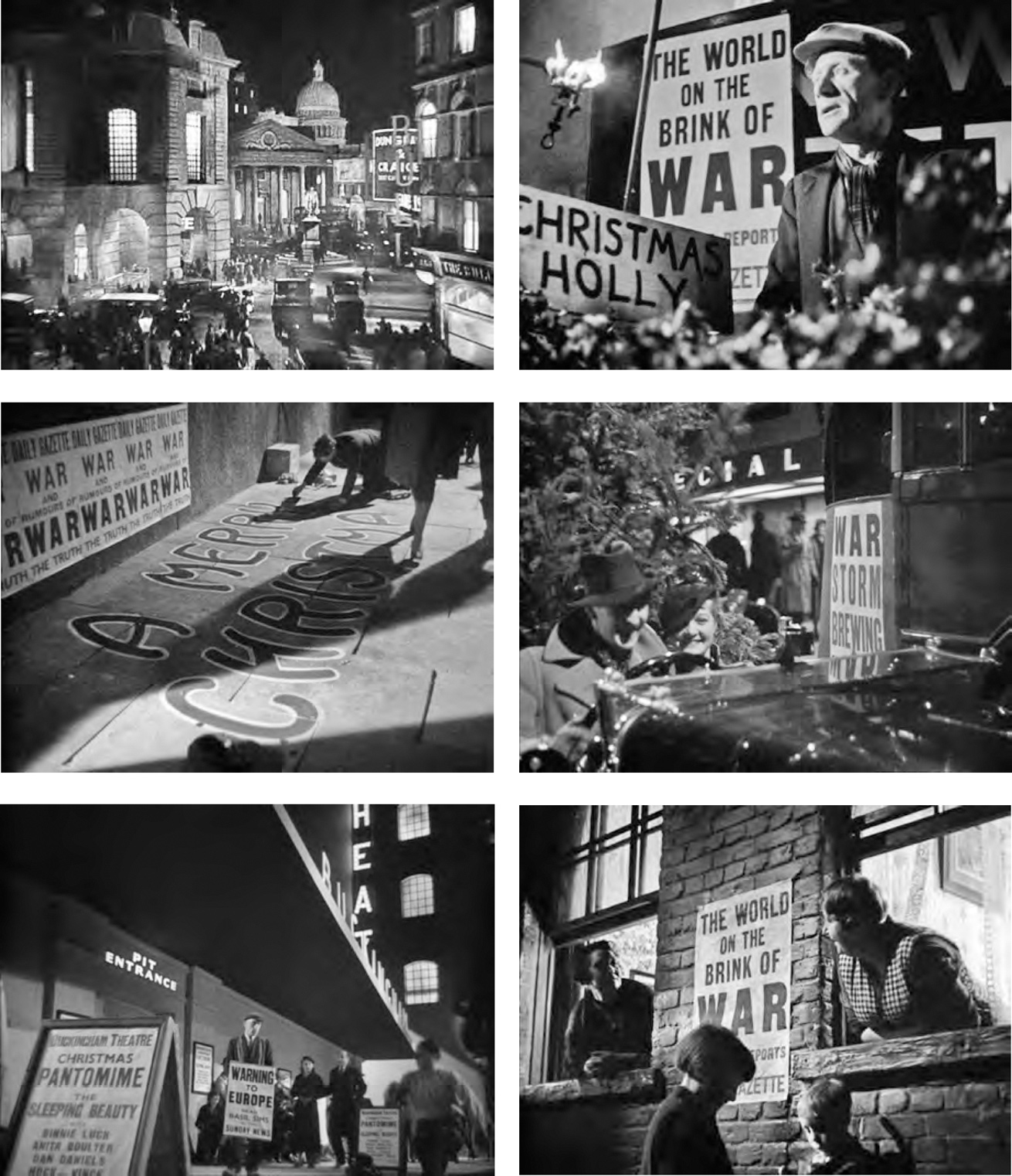

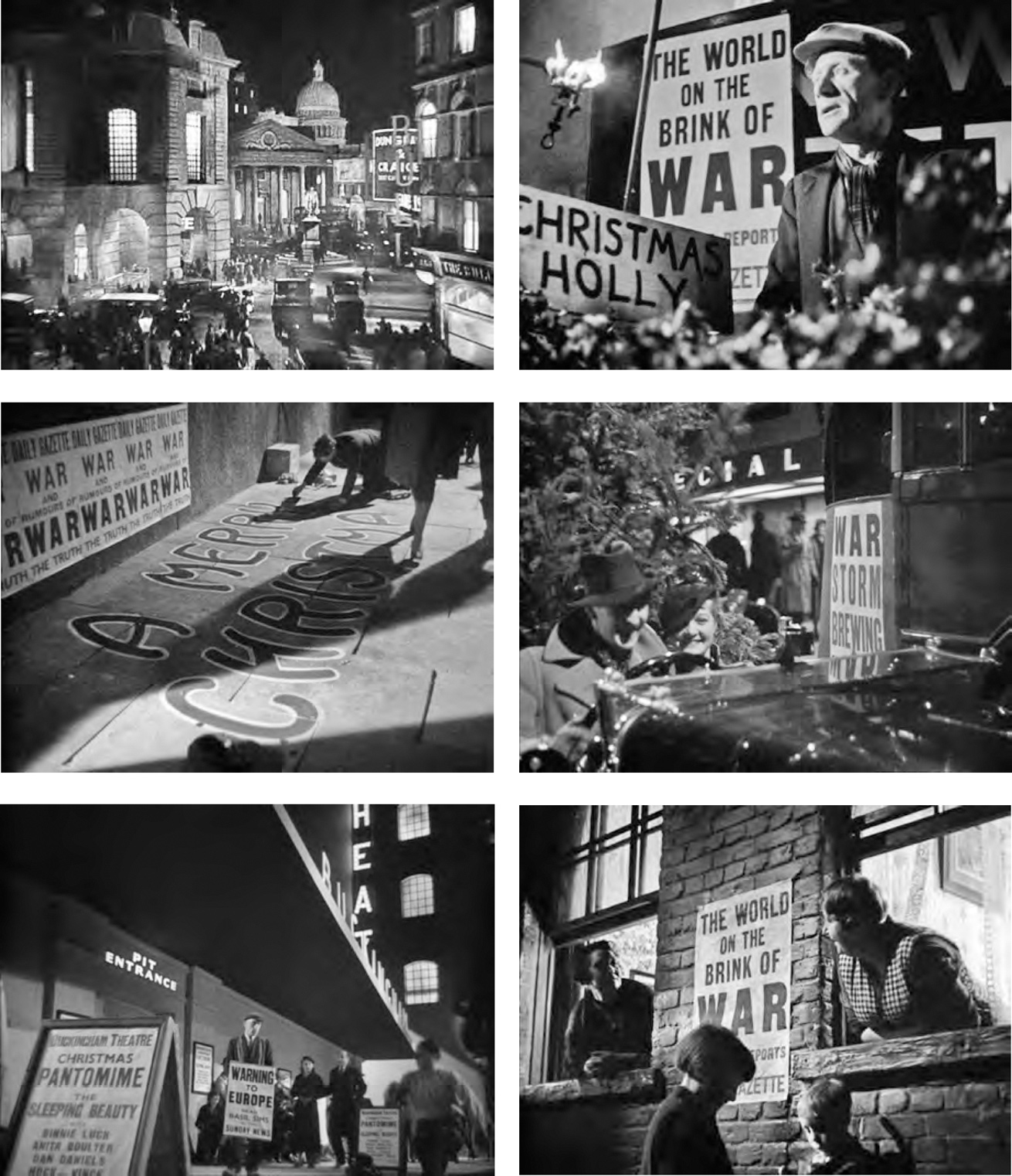

The opening montage was shot mostly on a vast stage at Worton Hall, Vincent Korda’s contemporary city anticipating Christmas 1940 amid the signs and shoutings of imminent war. A visitor from The Scotsman observed a huge set “representing the width of a street in the West End of London, with a luxury hotel on one side, and on the other a super cinema. Buses, taxis, cars, and bicycles filled the roadway, while the pavements were crowded with people.… On an adjoining stage was a set of a street from the East End of London, where cameras had recorded the effect of a bomb explosion during an air raid of the future war. Everywhere carpenters were busy constructing modernistic buildings of lath and plaster. Cameramen, electricians, and experts for this and that were moving about. There was a suggestion of intense, purposeful activity.”

Vincent Korda, meanwhile, was at work in his studio amid sketches of giant beetlelike tanks and houses and buildings of the mid-twenty-first century representing a style of architecture “as distinctive as that of Greece or of the Renaissance.” Said Margaretta Scott: “I think Menzies and Korda worked very much as a team, and the back-up people were terrific.” In addition to Korda, Périnal, Ned Mann, and the others, Menzies also acknowledged a “funny collection of Cockney prop men” he taught to shoot craps and who, he said, would “absolutely go through Hell and high water for me.” As decades of battle ensued, the advanced city of the present became the battered ruin of Everytown 1970.

“Well, Darling, everything is unbelievably jake,” Menzies advised Mignon in an uncharacteristically jubilant letter. “I am absolutely (at least for the moment) the white-haired boy, and yesterday’s dailies really gave me a thrill. I have two marvelous actors in Richardson and Massey, and Margaretta Scott is marvelous and is photographing like a million. Korda and Wells are both mad about the stuff, and everyone thinks it’s going to be the great picture.… I realize now what an awful thing Johnny [Considine] did to me when he started me off co-directing. If I had been on my own from the start, I don’t think I would ever have had the last awful three years.”

Nighttime exteriors took fourteen days (instead of the scheduled five) to complete and put Menzies on a regimen of box lunches and two or three hours of sleep a day. “Alex, I think, got to like the stuff better,” he said, “but I had the horrors as it was so slow and dawn came so fast.” Daytime brought its own set of worries, including endless waits for the sun to appear. (“We are shooting the desolation sequence, so we are full of ruin and anemic people.”) Raymond Massey, playing aviator John Cabal, one of the “last trustees of civilization,” remembered Wells as a constant presence on the set, though his involvement appeared to be limited to the close attention he paid the costumes adorning the female members of the cast. Menzies, however, was the frequent recipient of handwritten notes from the Great Man, generally pointing out how he had failed at the staging of an unplayable scene.

“Those final scenes of Cabal with the dead Boss & with Roxana will not do,” Wells said in a typical missive. “What is wrong with the Boss scene is Cabal’s delivery of his last line. He stands up & speaks it. But he ought to say it clearly & calmly to himself. Massey is an emotional man. That is his dangerous quality & here he has been allowed to be emotional almost to the point of shouting hysterically.” Wells went on to hammer the point, concluding that Menzies was focusing on all the wrong things. “All the Cecil de Mille effects of crowds & milling about & so on that you are spending so much thought & time & money upon do not matter a rip in comparison with the effective handling of this essential drama. They are very effective in their way, but they are not this film.”

In truth, however, they were. The striking visuals on which Menzies and his colleagues were laboring so hard were coming to define a film that was otherwise lacking in dramatic values. “The picture was fantastically difficult to act,” Massey stated in his autobiography. “Wells had deliberately formalized the dialogue, particularly in the later sequences. The novel’s realism had vanished from the screenplay in which we delivered heavy-handed speeches instead of carrying on conversations. Emotion had no place in Wells’ new world.” Though Wells admitted to “a state of fatigue” as filming dragged on, he diligently kept at Menzies and Korda and, sometimes, even the actors, convinced his film would suffer without a vigilance that bordered on the obsessive.

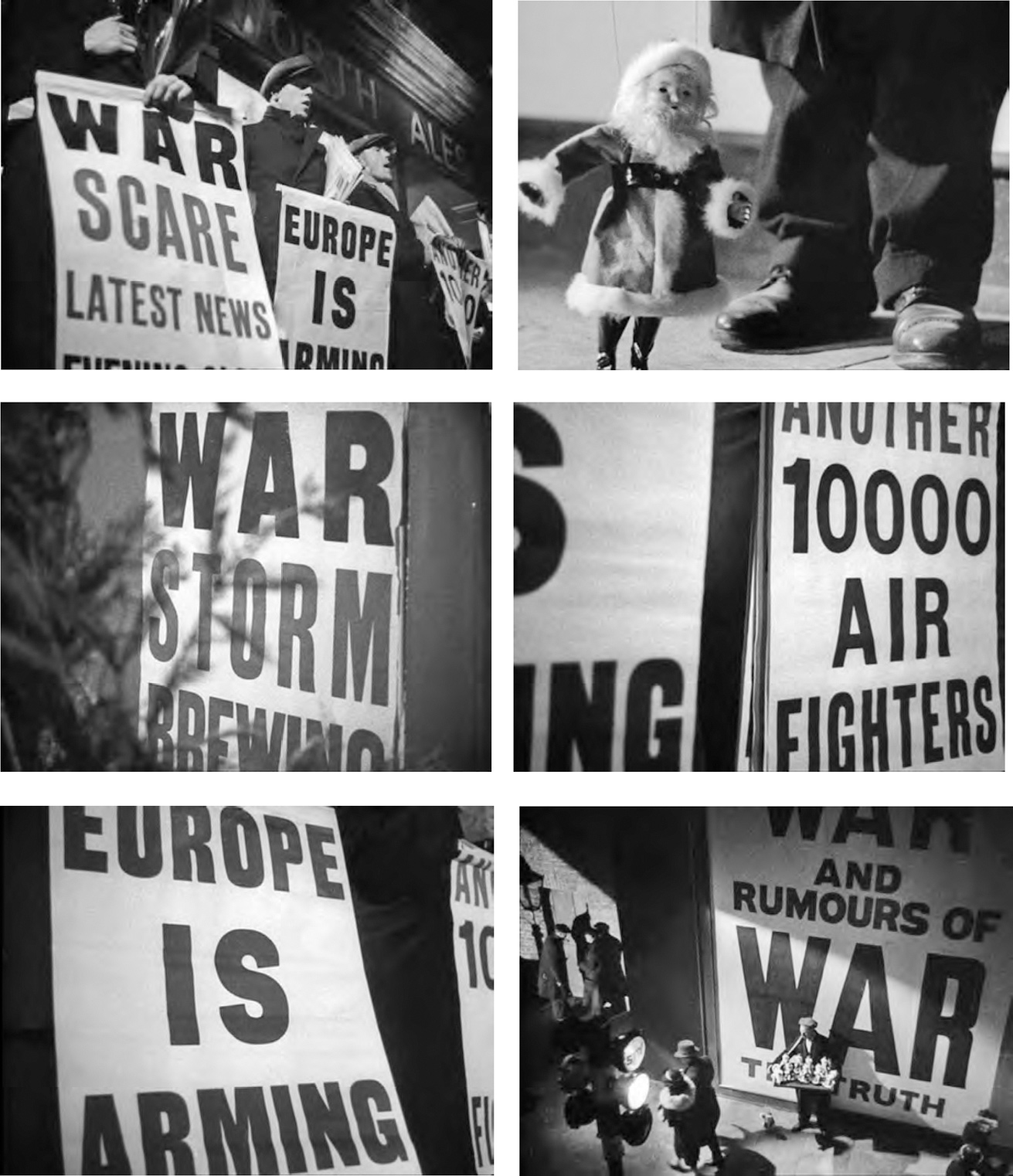

The death of the Boss in Things to Come (1936) illustrates the collaboration between Vincent Korda and William Cameron Menzies. The set is doubtless Korda’s work, but the composition, Cabal towering in the middle distance, the Boss’ crumpled figure in the foreground, is clearly Menzies’. (AUTHOR’S COLLECTION)

“Alex has gone away,” Menzies told Mignon on the 26th of August, “but I have been wrestling with Wells this week. I have pretty well finished the longer sequence I was on, but I have lost my perspective and I don’t know whether it’s good or not. I most certainly will be the happiest man in the world when it’s finished.… I am beginning on the really future, future world next week, and it might give me a new interest. The picture has a strange, believable reality that might make it terribly successful. I think generally my work has been good.”

By September 1935, the picture had been seven months in production and the end was only vaguely in sight. Alex Korda was meeting with United Artists executives in New York and Los Angeles and talking up a planned slate of thirty-six features in the press. He was, he told Eileen Creelman of the New York Sun, preparing to direct his own production of Cyrano with Charles Laughton in the title role. He added that he was eager to get back to England, where an American director, William Cameron Menzies, was finishing The Shape of Things to Come. When a press agent interrupted him with a reminder that the title Whither Mankind? had been changed to 100 Years from Now, the producer shook his head insistently. “No, no; it is The Shape of Things to Come. I have just had a peppery wire from H. G. Wells and he says it must be that.”

In England, Wells had written composer Arthur Bliss: “We are really getting the film in shape at last. In about ten days time I shall be able to show you the first two-thirds and up to the opening of the New World part continuous. Then you and I and the Director and the Sound Expert and the Cutter ought to sit down and look at it hard. Then you and the Sound Expert ought to do some fruitful discussion. The final part is being shot but at present no continuity is possible.”

At the time, Menzies was finishing up the desolation sequence and preparing to shoot the first scenes set in 2036, an episode that ends with an angry mob attempting to stop the firing of the Space Gun—a device out of Jules Verne that proposes to shoot a manned capsule into space as an ordinary firearm might shoot a bullet. Menzies had come to consider Vincent Korda impractical and knew it would fall to him to give the Space Gun the weight and drama it lacked as a miniature. “I felt a little better about the stuff today,” he wrote on September 7, “as I had a good day with beautiful clouds and damn near finished my exteriors. The particular set I am in has nearly driven me crazy—it’s been a jinx from the go. My main worry now is when the hell we will ever get this lousy picture finished. I saw a list of the first set of the new world, or rather the ‘Moon Gun’ sequence, and it was lousy, but like I always have to do, I am going to try and save it, but that’s what takes the time.”

Raymond Massey credited Menzies for the “swift and orderly progress” of the picture. “Things to Come was a difficult job for all of us,” he said. “We were always the puppets of Wells, completely under his control. Like all socialists, in his forecast of man’s future Wells saw nothing but authoritarianism. A bad dictatorship would be followed by a benevolent one. A benign big brother was bound to be a bore. He was the fellow I played in the futuristic part of the film. I could only act Oswald Cabal as calmly and quietly as possible and, as the saying goes, ‘Everybody was very kind.’ ”

A “puppet” who didn’t fare quite as well as Massey was fifty-six-year-old Ernest Thesiger, perhaps the most experienced actor in the cast. Thesiger’s role, as the rebel artist Theotocopulos, was to rile a mob of followers against the machinery of the modern age, to “talk all this machinery down” in a discourse over the televisor. Thesiger certainly seemed to fit the part, dramatically flourishing a great cloak as described in the text, but his scenes, when cut together, failed to establish him, in the author’s mind, as someone capable of rallying a group of ardent followers. Contending the character’s voice needed more vox humana, Wells demanded that Thesiger’s scenes be reshot with another actor, and when Korda returned to London he complied, engaging the younger—and somewhat more substantial—Cedric Hardwicke for the part.

Redemption on an international scale: Menzies poses with H. G. Wells and the ballerina and actress Pearl Argyle on the set of Things to Come. (AUTHOR’S COLLECTION)

As Menzies glumly reported in his letter of November 13, “I am more or less buried in retakes. Korda is a hound for them and, personally, I don’t think they are any great improvement.… I have been terribly worried about the picture lately, but I hope it’s just staleness. It’s at the point where you can’t tell much about it. Korda blows hot and cold too, which is rather discouraging and nerve wracking. I can’t seem to get back to my old gayness lately, but this thing is a terrible thing to have on your mind.” His mood wasn’t improved by a chance encounter with Douglas Fairbanks, who was all of fifty-two but looked “very old.” Wells, meanwhile, had gone to America, where he hoped to induce Charlie Chaplin to play the title role in his History of Mr. Polly. Sardonically, Menzies noted that Wells had published his treatment (under the title Things to Come) and had taken an awful panning for it. “We are all glad he has left,” he said of Wells. “Hollywood can have him, and I hope they like him.”

Retakes for the film’s final act were made at Worton Hall during one of the most savage of English winters. As the temperature hovered near zero Celsius, Raymond Massey found himself working on unheated stages in “abbreviated skirts and Tudor-like doublets of foam rubber and pleated buckram.” Mercifully, the scenes with Cedric Hardwicke, augmented by long shots still containing Ernest Thesiger, went quickly, Menzies having assumed a perfunctory attitude toward the bits and pieces remaining.

Here it is another Monday and the headaches still carry on. I have had a lot of re-takes, principally because I am so tired mentally I can’t think with any originality. Korda is a very difficult taskmaster, and is greatly affected by his yes-men.… I am nearly driven insane by delays, and Korda is getting rather sarcastic and ugly again.… It is maddening to have to work as I have this year and have nothing to show for it. But I think the picture will make it jake for me from now on.… Ray Massey is chafing at the bit. He is doing a play in New York. His wife has been there for several months. I would like to see the damn thing thru and, if it was just a question of a few days, see the premiere here, as I deserve a little kick out of all this work, and it being the biggest.

By the last of November, Massey had been given his release and Korda, who had been away, was screening the footage Menzies had shot in his absence. “Fortunately, so far he has liked it,” Menzies said in a letter to his family, “but he is looking at it in small pieces, which is a little like slow torture. He seems to be feeling swell. Naturally he is on the crest of the wave. He likes my modern world stuff a lot. Most of the stuff he gave me hell for he is gradually coming around to like.… Well, my dears, I start to see the end of it, and I hope I have a successful homecoming. I mean as far as the picture is concerned. It certainly is different and, I think, as well made as possible under the circumstances. They certainly have never made one like it anywhere.”

He was planning to spend New Year’s Eve at the Chelsea Arts Ball but fell ill instead. “Another reason for feeling low,” he added on the 11th of January, “is that Wells is back and is going to run the picture today, so I hope there aren’t a million changes. The first part of the picture is in good shape. I’m not so sure of the last.” Editor Francis D. “Pete” Lyon, who had been asked to recut and polish the first half of the film while Charles Crichton worked on the second half, witnessed the screening: “When the lights came on after the running, our eyes were on Mr. Wells, of course, because we wanted him to be pleased with our efforts to present his prized creation to the movie world. He slowly rose and paced in front of us for a few seconds, then turned and said, ‘There is only one thing wrong with this film—it is five years too soon.’ We were all relieved that he didn’t take us apart.”

With Wells’ approval, a preview was scheduled for the week of January 20, 1936, giving Menzies just two weeks to get the last of the effects shots into the picture. Then George V died at the age of seventy, causing the showing to be put off indefinitely. Menzies feared Korda would use the time to start fiddling with the picture again, hindering his best efforts to finally get the thing done. “Korda has the jitters and I suppose the King’s death won’t help it any, and I have a strong feeling of dog house again. Some of the faults are mine, naturally, for I am tired and sick of the picture, but as usual I take the rap for everything. Sets are never ready, and I have to shoot everything in a few minutes.… I have definitely decided to concentrate on getting independent in the next few years, as I really can’t take it anymore. 15 to 18 years of this worry and tearing your brain apart is too much, and I must accumulate some money and ease up a bit. I figure 3 to 5 years of hell and concentration on making money, and then some peace of mind. I feel ninety and am beginning to look 100.”

The world premiere of Things to Come took place on February 21, 1936, at UA’s Leicester Square Theatre, the day after the British Board of Film Censors awarded it an “A” certificate at a running time of 117 minutes. The program began at 8:45 with an edition of World News Bulletin and a Mickey Mouse cartoon. Recalled Cedric Hardwicke, “My work in Things to Come was completed with such speed and lack of ceremony that the actor I had replaced had no idea that his entire performance lay on the cutting room floor. He arrived with a party of expectant friends at the London premiere, an exceedingly fashionable gathering. After his disappointment, I remained pleasantly surprised that he did not become my enemy for life.”

What the audience witnessed that evening bore little resemblance to any British movie they had yet seen. The London Film logo, Big Ben chiming against a cloud-filled sky, gave way to a monumental set of credits, unparalleled in size and weight, the portentous music of Arthur Bliss ringing out a grim, dissonant warning of what was to pass in the opening minutes. Up on a bustling Everytown, Christmas 1940, chorales heralding frantic scenes of celebration, the streets awash with traffic. A young boy in stark close-up eyes a toy in a shop window; a joyous couple drive along, a Christmas tree loaded into the back of their sleek roadster; Christmas holly piled high atop a vendor’s cart as the ominous image of a News Gazette truck pulls into view, its side plastered with the words THE WORLD ON THE BRINK OF WAR. A militaristic march intrudes on “God Rest Ye Merry Gentlemen,” the word WAR populating the background, subtly at first, then insistently amid flashes of Christmas turkeys and pantomimes, street vendors and carolers, handbills and posters, their letters progressively larger, more harrowing: RUMOURS OF WAR … EUROPE IS ARMING … WAR STORM BREWING …

It was a spectacular couple of minutes, the sort of thing Menzies had done for others in the past, now on full view as a work entirely of his own, the most flamboyant and unsettling bit of filmmaking he had yet afforded himself, the work of a man at the very pinnacle of his powers as a visual artist. Hampered by Wells’ declamatory dialogue, he could do little with the early exchanges between Cabal and the industrialist Passworthy, the latter disparaging the possibility of war even as forces are mustering and an air attack is on the way. Another urgent montage set the tone for the film, sequences of astonishing size and pattern alternating with tedious rounds of dialogue, fine, stage-trained actors struggling with words better left read than spoken. The fortification of Everytown and the subsequent air attack, effectively depicting the London blitz as happening within four months of its actual occurrence, was accompanied by music so intrinsic that Wells had wanted it recorded in advance of production. “This Bliss music,” he insisted, “is not intended to be tacked on; it is part of the design. The spirit of the opening is busy and fretful and into it creeps a deepening menace.”

As the film progressed, it became evident that the strength of Things to Come lay in its sweep and vision, its hundred-year dream of rebirth having overwhelmed any hope of dramatic validity. The years of war come to desolation and the rule of a petty despot, while the wandering sickness (“a new fever of mind and body”) afflicts the populace. Into the scene flies an aged Cabal, his garb and demeanor presaging a utopian future. (“And now for the rule of the Airmen,” he intones over the dead body of the Boss, “and a new life for mankind.”) Little more than an hour into the picture, the reconstruction of Everytown begins, a process that stretches from 1970 to the year 2036 and reveals a vast cavernous city anticipating the atrium hotel designs of John C. Portman. Wells called for “one of the high-flung City Ways” displaying “the very bold and decorative architecture of this semi-subterranean city and the use of running water and novel and beautiful plants and flowering shrubs in decoration. In the sustained bright light and conditioned air of the new Everytown, and in the hands of skillful gardeners, vegetation has taken on a new vigor and loveliness. People pass. People gather in knots and look down on the great spaces below.”

Menzies’ influence on Vincent Korda was most readily apparent in the point of view he imposed on a scene, giving the muscular streamline that dominated the latter part of the picture a grace and energy all its own. Though the designs may well have been Korda’s, their lines filled the frame by way of Menzies’ compositional eye, and he favored deep perspectives and low angles, ensuring his figures would “read” against walls, ceilings, or cloud-filled skies, building the strength of his compositions on suggestion as much as actual detail.

The architecture of the future Everytown came in concentric circles, automated work crews assembling the great city as one might an elaborate layer cake. “Only the lower part of that set is real—up to and including the third platform,” Ned Mann pointed out at the time. “The figures on and above the fourth platform are dummies attached to a model. All the curved background is in miniature.” What Mann described was, in fact, a “hanging” miniature—a model suspended a few feet in front of the camera and carefully registered with the partial set in the distance. The film made use of many such models, which gave it the richest possible look without the expense of actually building the sets they represented. The climactic firing of the Space Gun, for example, was accomplished with a series of miniatures.

“On the screen this gun appears gigantic, reaching up into the clouds and dominating the surrounding landscape,” said Mann.

But the model for a long shot was no more than 20 feet high and made of thin sheet metal. The clouds and the direction of lighting required special care. The clouds were not painted on a backcloth, which would have looked flat and stagy. They were created out of smoke, so that the sky was a miniature of the real thing. Sunlight streaming in from one side we imitated with a spotlight. For the closer shot of the Space Gun we used a larger scale model; for, with the detail so enormously magnified, absolute accuracy was essential if a crude result was to be avoided on the screen. In this case we employed similar smoke clouds, and a powerful spotlight casting sun shadows to give greater depth and relief to the picture.

The film ended on an uncertain note, the latter-day Cabal and Passworthy following the progress of the space bullet on the giant mirror of a telescope and debating the eternal struggle of human advancement. “My God!” exclaims Passworthy. “Is there never to be an age of happiness? Is there never to be rest?”

“Rest enough for the individual man,” Cabal responds. “Too much of it and too soon, and we call it death. But for Man no rest and no ending. He must go on—conquest beyond conquest. This little planet and its winds and ways, and all the laws of mind and matter that restrain him. Then the planets about him, and at last out across immensity to the stars. And when he has conquered all the deeps of space and all the mysteries of time—still he will be beginning.”

“But—we’re such little creatures,” Passworthy says. “Poor humanity, so fragile, so weak—little, little animals.”

“Little animals—And if we’re no more than animals we must snatch each little scrap of happiness and live and suffer and pass, mattering no more than all the other animals do or have done … All the universe is nothingness … Which shall it be, Passworthy? Which shall it be?” And then the chorus rises on the infinite display of deep space before them: WHICH SHALL IT BE? WHICH SHALL IT BE? WHICH SHALL IT BE?

H. G. Wells, perhaps sensing the mixed reaction of the audience, was dismayed. While willing to assume some of the blame for his “mess of a film,” he disproportionately blamed Alex Korda, who had afforded him unprecedented influence, and Menzies, who was, in reality, responsible for much of what the audience seemed to respond to and like. “For me it was a huge disillusionment,” Wells wrote privately not long after the premiere.

It was, I saw plainly, pretentious, clumsy, and scamped. I had fumbled with it. My control over the production had been ineffective. Cameron Menzies was an incompetent director; he loved to get away on location and waste money on irrelevancies; and Korda let this happen.*2 Menzies was a sort of Cecil B. De Mille without his imagination; his mind ran on loud machinery and crowd effects. He was sub-conscious of his own commonness of mind.… The most difficult part of this particular film, and the most stimulating to the imagination, was the phase representing a hundred and twenty years hence, but the difficulties of the task of realization frightened Menzies; he would not get going on that, and he spent most of the available money on an immensely costly elaboration of the earlier two-thirds of the story. He either failed to produce, or he produced so badly that ultimately they had to cut a good half of my dramatic scenes.

The extraordinary Christmas Eve montage that opens Things to Come. “It’s just with extras and atmosphere,” Menzies wrote, “but it’s the kind of thing I do best.”

When Wells wrote of his “dramatic scenes” he meant, of course, the endless speeches that brought the action to a screeching halt. As the author, he could not recognize nor acknowledge the essential contribution that Menzies—and Vincent Korda and Ned Mann and Georges Périnal and their associates—had made in keeping the film consistently interesting, if not necessarily involving. The critics who had previewed the film the previous night, however, had little trouble in doing so.

“When America sees this film it probably will regard it as the most important ever to come out of a British studio,” predicted the London correspondent for the Motion Picture Herald. “From such dispassionate viewpoint as a British reviewer may claim, it seems that America will be right.… The audience found the glimpses of the future breathtaking and applause was prolonged for individual sets and effects. Women and some men criticized the lack of ‘story.’ Objection to the arid Wellsian world was common; but its picturization was thought ‘marvelous.’ ” The Variety report was even more damning of Wells while praising the film’s technical properties. “William Cameron Menzies is the director, and for lavishness of treatment and decor, and skillful mixture of illusionary devices of expert camera tricks and sound necromancy, it surpasses in scope anything which has come from Hollywood.… Because it is a departure from routine paths, and as such is to be commended, it will be viewed as an experiment successful in every respect except emotionally. For heart interest Mr. Wells hands you an electric switch.”

Things to Come fared better in the secular press, where nationalistic pride in the sheer scope and magnitude of the £256,000 picture—by far England’s most expensive—drew plaudits from most of the London dailies. “It is a leviathan among films,” said Sydney Carroll in The Times.

It makes Armageddon look like a street row. It shows science flourishing the keys of Hell and Death, and creating from the ruins of Everytown crazy labyrinthine cities radiant with artificial light, teeming with crowds of art-starved people craving for old excitements and former thrills. A stupendous spectacle, an overwhelming Doréan, Jules Vernesque, elaborated Metropolis, staggering to eye, mind, and spirit, the like of which has never been seen and never will be seen again. When twenty minutes of repetition have been cut from it, it should obtain a wide world sale. It makes film history.

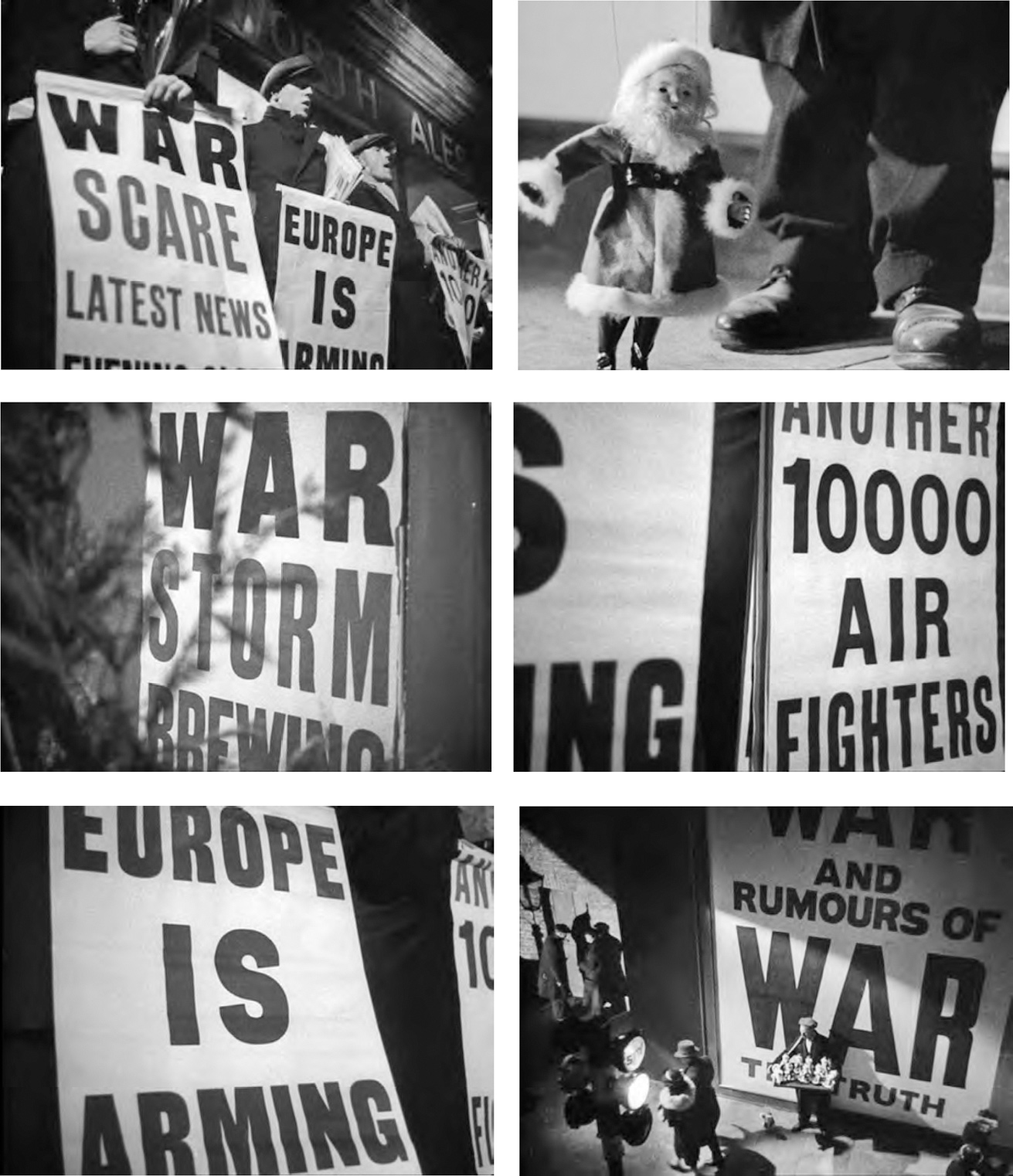

The subterranean Everytown of the year 2036, probably the most famous single image from Things to Come. Generally credited to Menzies, who would have influenced the composition, it is more likely the work of Vincent Korda, who drew upon a range of influences to produce what Christopher Frayling has called “a grandiose fusion of Le Corbusier and American streamlining.” (AUTHOR’S COLLECTION)

Alistair Cooke, writing in The Listener, broke with the herd in a somewhat dismissive notice that took Wells to task for bad acting, dialogue, and psychology. “In a film showing the death of a nation and its rebirth in a new age of sight and sound, the only people who must have imagination are the scene designer, the director, and the cameraman. And the achievement of Things to Come is no more and certainly no less the ingenious hours spent around little white models by William Menzies, Vincent Korda, and Georges Périnal.” Yet C. A. Lejeune found such criticisms petty, considering that for the first time the medium had been used to state “a hard and fairly complex argument” with force and beauty. “It is very easy to nag at Things to Come,” she wrote. “When a thing is so big that the imagination cannot quite embrace it, there is always a picking and scrambling at the detail. At a dozen points the film is vulnerable, and I have no doubt at all that it will go out into the world stuck full of Lilliputian arrows. But not one of them will measure its stature nor impede its power.”

Passworthy and Cabal stand before a telescopic mirror at the conclusion of Things to Come, observing the progress of the bullet fired from the Space Gun. For a film built on bold graphic ideas, going big with this final set was an imperative. (AUTHOR’S COLLECTION)

For the next few weeks, it seemed that all business in London was directed at two United Artists releases—Chaplin’s Modern Times and Things to Come. Early into its run, it was decided to trim the film by a full reel—nearly ten minutes—in advance of a wider release pattern. Menzies may have had input, but by this point he was en route to New York aboard the Bremen, where, accompanied by Ned Mann, special effects assistant Lawrence Butler, and editor William Hornbeck, he would give Korda’s partners at UA their first look at the finished product. “We ran the show for United Artists and the opinion was divided,” Menzies recounted in a final letter to California, “altho all agreed it was too long. I hope Korda will agree to cuts, as I think they are right.… I am a little worried that the picture is a great technical achievement rather than a dramatic success. However, I don’t think it can do anything but help me. Damn that old fool Wells.”

Menzies was another six weeks in New York, overseeing the cutting of the picture to a final running time of ninety-six minutes. Eager to see his family, he stopped just short of attending the premiere at New York’s Rivoli Theatre, instead boarding a Transcontinental and Western DC-2 bound for Los Angeles. On the morning of April 19, he arrived home after a grueling eighteen-hour trip that included refueling stops in Chicago, Kansas City, and Albuquerque. Gathered to meet him were Mignon; Jean, now fifteen and in high school; and Suzie, who was just eight when her father left for England. After an absence of nineteen months, his Scottish mother, effusive as ever, greeted him with a handshake.

Awaiting him also was an urgent cablegram from Korda:

RETURN BY NEXT PLANE.

*1 A detailed analysis of Vincent Korda’s various influences and inspirations can be found in Christopher Frayling’s Things to Come (London: BFI Publishing, 1995).

*2 Unfamiliar with film terminology, Wells apparently considered anything not contained within the walls of a soundstage to be “location.”