13

GWTW

The first rushes were up on Tuesday, and nearly everyone got a look at the spectacular fire footage, wondering how it would all fit together. With the clearing of the site already under way, Menzies turned his attention to a model of Atlanta that was housed in Jock Whitney’s office, Selznick, Cukor, and the others gathering to discuss the assemblage of false fronts that would be finalized within days. The producer’s mania for detail extended to the proper shade of red for the Georgian clay, and Wilbur Kurtz had a box of it shipped to his Culver City hotel. Essentially finished with Made for Each Other, Selznick told Menzies that he would see him anytime, dispensing with the routine of appointments that usually had to be made a day in advance.

Regarding Tara, Selznick wasn’t satisfied with any of the drawings produced by Menzies and Lyle Wheeler. “He wants a dream house,” Kurtz concluded, “not an architectural monument.” Menzies said he would “get right on” another drawing and that he’d do a composition this time rather than a rendering. Cukor, meanwhile, had his own ideas of how the house should look, and Kurtz noted the art department had thrown just about everything into its design of Tara other than round columns. They continued to wrestle with the look of “the most important house in the world” through Christmas. By New Year’s Eve, the barrel-vaulted car shed had been framed, part of the roof was in place, and the plaster sheet brick was ready to be applied. Nearby, on a graceful rise of ground, the foundations of Tara had been laid and its framing was finally at hand.

Selznick, meanwhile, was revising Sidney Howard’s screenplay in collaboration with Oliver H. P. Garrett. On January 6, 1939, he heralded the completion of the first pages in a memo to the production team:

Commencing with the first final scenes, which will come through today on Gone With the Wind, I will expect Messrs. Menzies, Kern, and [cinematographer Lee] Garmes to meet regularly and lay out their conceptions of the camera angles to the end that we may all know, in advance, exactly what we are going to get in the way of lighting and set-ups; and to the further and even more important end that we may do a job of pre-cutting with the camera that is greatly more economical than has ever been attempted before.… I will want Menzies and his staff to sketch for me each angle and before we go into each sequence I will go over these and make any changes that I think are necessary before we go over it with Mr. Cukor.

Selznick was, in effect, preparing to direct the film by proxy, Menzies putting his artistry at the producer’s disposal and rendering a mise-en-scène that would essentially straitjacket the director. Over the course of production, literally thousands of conceptual illustrations would be generated by the Selznick art department. Of the larger pieces, which conveyed nuance and color, Menzies did more than his fair share, but just as many were done by Dorothea Holt and Joseph McMillan “Mac” Johnson, both of whom had styles all their own. Yet, when it came to continuity boards, the panels that emphasized composition and the progression of story over detail, most were done by Menzies alone. “The first thing I do in starting a sketch,” he said in a 1938 interview, “is to draw in circles for the faces of the actors. I figure out the set as a background to the group, even taking into consideration how many feet an actor will have to walk to get from center stage to exit at left center. So it’s really a sort of precutting of the picture.”

The exterior of Tara was nearly finished by the 11th of January, when grading was in process and Menzies decided the proper color of Georgia clay could be achieved with ground brick. On Monday, January 16, Henry Ginsberg called a meeting at which he informed the department heads that production would commence on the 23rd—and to a man they all said they couldn’t be ready. The Tara interiors were going up on Stage 3, the woodwork a powder blue, and painters were at work on a huge backing that would depict a landscape of fields and pines. Out on Forty Acres, exteriors were nearly camera-ready, and Peachtree, constructed along a rutted roadway over the facades of standing sets, was crawling with workers.

The first one hundred pages of Garrett’s script were widely distributed the following day, giving everyone a first look at what was presumed to be the shooting final. A week later Selznick dispatched a copy of the “so-called Howard-Garrett script” to Jock Whitney in New York.

Menzies poses with the art department staff assembled for Gone With the Wind. Looking over his shoulder (in hat) is the credited art director, Lyle Wheeler. (DAVID O. SELZNICK COLLECTION, HARRY RANSOM CENTER)

The only thing that I can see that might get us into trouble would be for me suddenly to be run down by a bus, so you’d better get me heavily insured. As long as I survive the whole situation is well in hand: the whole picture is in my mind from beginning to end; all the sets for the first six weeks of shooting are approved in detail; all the costumes approved; the entire picture cast with the exceptions only of Belle Watling and Frank Kennedy, who don’t work for some time; and generally the picture is, I assure you, much better organized than any picture of its size has ever been before in advance of production.

Filming actually began on January 26, 1939, with a long shot of Scarlett O’Hara running down the steps of Tara and along the walk toward the eventual arrival of her father, the soil appropriately reddened with a dusting of brick and the dogwood blossoms in all their artificial glory. It would be the first of approximately one hundred matte shots made under the supervision of Jack Cosgrove, who had encouraged the extensive use of matte paintings on glass or Masonite as a way of saving money on the building of sets. (“Jack,” said Clarence Slifer, “was a great man for spotting opportunities for matte shots and to convince the director that he needed them.”) Equipment problems and fog plagued the company that day, and the afternoon was given over to work in Scarlett’s bedroom, Vivien Leigh playing her first scenes with singer-comedienne Hattie McDaniel, who had won the coveted role of Mammy, the slave who had been Scarlett’s nurse from birth. With the design of the sets settled, attention turned forcefully to how they—and the actors—were being photographed, and shooting was held up nearly an hour as Lee Garmes and representatives from Technicolor debated the amount of light flooding the small room. Leigh’s stand-in wilted as sections of wall were alternately erected and taken down, all to make room for lights that may or may not have been necessary.

Frank Nugent, on hand for The New York Times, described the situation “an unconscionable to-do” given the crush of resources suddenly brought to a halt.

William Cameron Menzies, the art director, was running all over the place, squinting through the camera with Lee Garmes, conjuring up a window frame to cast its shadow decoratively across a four-poster bed, bloodthirstily commanding the men on the catwalks to “kill that broad.”*1 Walter Plunkett, the dress designer, had a couple of sketches desperately in need of director George Cukor’s approval. Mr. Cukor, oblivious to Mr. Plunkett, was looking for someone called Charlie, and Charlie was busy applying a last-minute coat of paint to the back of a mirror we are sure won’t ever appear in the completed shot.

Two days later, Selznick issued a memo deploring

the conflicting opinions about color among members of the art departments, officials of the Technicolor company, etc., if we are to avoid confusion, loss of time and waste of money through such ridiculously unnecessary things as repainting sets, etc. I should like to reiterate that Mr. Menzies is the final word on these matters and should be the arbiter on any differences of opinion. I hold Mr. Menzies responsible for the physical aspects of the production and for the color values of the production, and any difference of opinion should be settled by him, hopefully without delay or equivocation.

Menzies had worked in color before—the old two-color variety in the 1920s and early 1930s, and the new three-strip process on Nothing Sacred and Adventures of Tom Sawyer—but only for isolated sequences, never for an entire picture. Now, faced with designing Gone With the Wind in color from beginning to end, he abandoned the stark images he favored in black-and-white for a pastel look that lent itself to variations in tone and intensity according to the dramatic needs of a scene. He could also see the progression of the story in terms of what Richard Sylbert later characterized as “musical ideas”—moods and passages of color that brought a symphonic cohesion to the action and built to highpoints in the narrative.

In handwritten notes made after he finished the picture, Menzies described his approach to color values on Gone With the Wind and the overriding philosophy that guided his choices. Color was intensified to heighten the drama, lessened to accentuate patterns, times of day, and physical conditions. “No attempt was made to make Gone ‘pretty-pretty,’ ” he wrote. “When unpleasant colors were required to enhance the drama they were used and the spectrum was reduced often to punch up conditions for dramatic effect. Severe red skies & Indigo backings were planned for macabre strong & unhappy atmosphere, as were soft combinations of pleasant colors for an opposite condition. Times of day were, I think, gone farther into in [terms of] color study than ever before. For instance, pre-dawn, dawn, evening, cold days, hazen skies for discomfort & heat, etc.”

Practically all the material shot over the first few days of production would have to be done over. Hairstyles were wrong, colors proved unacceptable, and actor Robert Gleckler died before completing his scenes as Jonas Wilkerson. Since the new Technicolor stock required 40 percent less illumination, the decision was made to deliberately underlight the O’Hara family’s evening prayer service, an experiment that elicited another memo from the producer deploring photography “so dark as to bewilder an audience.” Wrote Selznick: “If we can’t get artistry and clarity, let’s forget the artistry.”

The first truly memorable sequence in the picture was initially not so memorable. It came with Gerald O’Hara’s paean to the land, his arm around Scarlett as they regard Tara in the distance. (“It’ll come to you, this love of the land. There’s no gettin’ away from it if you’re Irish.”) It was a Cosgrove shot, made on the backlot, Tara as situated on Forty Acres, perfectly respectable but pastoral and static. Gerald’s hair was all wrong, as was the landscaping, yet a retake showed no real improvement. Six weeks into production, Selznick decided they had been kidding themselves “in feeling that we could get really effective stuff on the back lot that should have been made on location.” He thought the walk of Gerald and Scarlett, which came straight from Margaret Mitchell, looked on-screen as though “it were the back yard of a suburban home” and predicted that it would have to be remade. He wrote Ray Klune: “I’d like you and Mr. Menzies to get together immediately to make sure that our remaining exteriors, such as the exterior of Twelve Oaks and the shot in which Gerald talks about the land being the only thing that matters (even if this is shot on the stage) have real beauty instead of looking like ‘B’ picture film.”

It was while the company was on location at Pasadena’s Busch Gardens that Menzies, in consultation with Cosgrove and Clarence Slifer, worked out a fix to the problem by adding motion and depth, the camera retreating to reveal the foreground figures as framed by a massive oak tree, the emphasis on the plantation before them and Scarlett’s birthright as Gerald’s eldest daughter. “They,” recalled Slifer, “were to be in silhouette against a sunset sky (a plate made after [a] big rain storm in 1938) with Tara (matte painting) in the background. I planned this shot to be composited on our new printer, using an aerial [projected] image of the Tara painting.” The tree itself was a cardboard cutout.

Menzies later described “the almost imperceptible darkening and enriching of the values and color until we achieve the violent contrast of the pullback shot. Cosgrove painted the distance in what is called close values and cool colors which, against the violent blacks of the tree and the silhouetted figures, gave a very convincing effect of depth and distance.” The run-up to the shot was similarly modified. “Throughout the walking sequence, the colors were designed to become cooler and darker (blues and violet), giving the feeling of approaching night. The significant achievement was in going from an idyllic, fairly light scene, when Scarlett and Gerald meet in the meadow, into a strong dramatic effect of darkness to point up Gerald’s lines about the meaning of land to the Irish, and blending them without shock.”

On Friday, January 27, Menzies directed second unit footage of the barbecue at Twelve Oaks, detailed material that would eventually be deleted from the movie. The next major sequence to be tackled was the Monster Bazaar held to raise money for Atlanta’s military hospital, a riot of colors that demanded a less nuanced reading.

In the bazaar sequence, when Scarlett horrifies Atlantans by dancing in widow’s weeds, symphonic color had to be sacrificed for a certain degree of realism in order to produce an effect of a ballroom decorated by local folks, yet at the same time its brilliance had to be overdone a bit to contrast with the later drabness illustrating the disintegration of the South. This was also true to a degree in the Twelve Oaks barbecue sequence, where we played a high key of brilliant colors, particularly in the costumes and sunshine effects of the outdoor scenes. The dark silhouettes of Ashley and Melanie in the foreground as they go from the house to the terrace accentuates the bright sunshine and gay costumes beyond. This was done particularly to afford contrast to the scenes at Twelve Oaks when it is in ruins, a shambles in the steely blue-gray dawn.

Cukor worked nearly a week on the bazaar, a sequence that would establish the ferocious attraction between Scarlett and Rhett. He moved on to the “green bonnet” scene that follows Rhett’s return from Paris, and then, on February 7, settled in for three days on the “birthing scene.” Plenty of objections had issued forth from the Breen Office, most concerning Melanie’s anguish during the birth of her son. (“There should be no moaning or loud crying and you will, of course, eliminate the line of Scarlett, ‘And a ball of twine and scissors.’ ”) It fell to Menzies to underscore her suffering in profiles of stark black and sharp, knifelike patterns of yellow, no light falling on the shutters or the human figures in the foreground, simply a white backing reflecting the colored glare of floodlamps through the slits. “Orange is a hot color,” he commented, “and with black it’s violent.… That suggested the hot afternoon as well as the violence of childbirth in those days. No scene of this combination can be held long on the screen. It will tear an audience to pieces.”

Rhett’s arrival at Miss Pitty’s house signaled the start of their flight to Tara and the gauntlet of the burning rail yard, but trouble was mounting between Cukor and Selznick, and this would be some of the last footage shot under Cukor’s direction. In November 1938 Selznick had written Menzies on the subject of Cukor’s perceived extravagances:

I have always felt that the shooting of two or three hundred thousand feet to secure an eight or nine thousand finished picture is, on the face of it, absurd.… On Gone With the Wind a more thorough camera-cutting becomes not merely desirable, but actually almost essential, if we are to bring the picture in at a cost that is not fabulous. This is particularly true because we will find that Cukor will probably eat up a great deal of film—and I need not go into the expense of Technicolor film—through the number of takes, although I have already spoken several times to George about the necessity of his doing more rehearsal where desirable and shooting less takes, to hold down costs, and I intend to watch this very carefully and to go into it with George again and again if necessary.

Selznick’s admonitions didn’t do much good; Gable, for instance, had to carry Olivia de Havilland down the stairs at Aunt Pittypat’s a dozen times before the director was satisfied. And Leslie Howard, in an early letter to his daughter, complained that after seven days of shooting they were five days behind schedule. Cukor, meanwhile, was equally unhappy with Selznick’s incessant rewrites, which made advance planning difficult and frequently rendered Menzies’ sketches obsolete.

“He had a very good script, written by Sidney Howard, but David kept fooling around with it,” Lee Garmes said. “All the preparatory work was based on Sidney Howard’s script, but when we started shooting, we were using Selznick’s. His own material just didn’t play the same. Cukor was too much of a gentleman to go to Dave and say, ‘Look, you silly son-of-a-bitch, your writing isn’t as good as Sidney Howard’s.’ He did the scenes to the best of his ability and they wouldn’t play.”

Matters came to a head on Sunday, February 12, when it was determined that Cukor, by mutual consent, would leave the film. A statement was issued to the press blaming “a series of disagreements” for the rupture and declaring the only solution “is for a new director to be selected at as early a date as is practicable.” George Cukor’s final day as director of Gone With the Wind was February 15, 1939.

“After the first ten days of shooting,” remembered Ray Klune, “we only had twenty-three minutes of film—and ten of those had to be re-shot.” On February 16, production was suspended at a carrying cost of $10,000 a day. Within hours, Victor Fleming had agreed to be the new director, Selznick’s first choice, King Vidor, having turned down the assignment. “When Cukor left,” said Lee Garmes, “we closed down the picture for a week or so, and Victor Fleming looked at the tests and the finished stuff. He didn’t give a damn what he said to Selznick, because he was on loan from Metro, so he told him point blank, ‘David, your fucking script is no fucking good.’ He demanded the Howard script back. He got it back.”

Fleming had, as the director of Red Dust, fashioned Clark Gable’s hard-charging screen persona in his own image—except that, in the opinion of many, Fleming, at age fifty, was better-looking than Gable. When production resumed on March 2, he was put to work reshooting a lot of what Cukor had done—Scarlett’s introduction with the Tarleton twins, Gerald’s walk with Scarlett, parts of the Atlanta bazaar. Several matte shots had been made under Cukor’s direction, including Rhett, Scarlett, and the others preparing to flee Aunt Pitty’s house, and now Menzies filmed their departure in accordance with the conceptual drawing Wilbur Kurtz had so admired, the single camphene lamp left lighted on the sidewalk. The fire sequence itself was continually being rewritten, incorporating the footage shot December 10, but with Selznick trimming it back when the stunt doubles, to his mind, looked more like doubles than the actors they were supposed to represent.

In time, Selznick came to decide that Lee Garmes’ work was much too dark, and a week after Fleming resumed production, Garmes was released as cameraman. “I worked for about ten or twelve weeks,” Garmes recalled. “We were using a new type of film, with softer tones, softer quality, but David had been accustomed to working with picture postcard colors. He tried to blame me because the picture was looking too quiet in texture. I liked the look; I thought it was wonderful, and long afterwards he told me he should never have taken me off the picture.”

Significantly, Garmes was replaced by a man who had even less experience in color, Warners’ Ernest Haller. It was Haller who shot Jezebel the previous year, and who would now finish Gone With the Wind in tandem with Technicolor’s own Ray Rennahan. On Saturday, March 11, Fleming and Haller shot the famous “war talk” sequence in the newly completed dining room at Twelve Oaks, Rhett forcefully breaking with the Southern fervor for war. (“Has any one of you ever thought that there’s not a cannon factory in the whole South, and scarcely an iron foundry worth considering? Have you thought that we wouldn’t have a single warship and that the Yankee fleet could bottle our harbors up?”) At once the rushes crackled with excitement.

Both Vivien Leigh and Olivia de Havilland had protested Cukor’s removal from the picture, and few were fond of Fleming or his determination to “make this picture a melodrama.” The only direction Leigh said she ever got from Fleming was “Ham it up!” And Marcella Rabwin, Selznick’s executive assistant, plainly thought him a bastard. “He did not like Mr. Selznick,” she said of Fleming.

I think he did not like almost everybody in the world except Clark Gable and himself. But he did something—he revitalized the whole theme of Gone With the Wind. Suddenly things began to happen. The girls didn’t realize that [in] their crying for George Cukor, but what’s happening is that the film has spirit and tempo. He was a very, very fine director even though I personally couldn’t stand the language that he used on the set, the way he treated Vivien Leigh—he was very harsh with her. I don’t wonder that she cried for George because George was a very sympathetic and passive person with her. He allowed her to be what she felt the role should be, but Fleming didn’t. Fleming demanded of her that she be the bitch that she was described as.

Leslie Howard, who considered it a badge of honor never to have read the book, returned the week of March 20 to play the scenes representing Ashley’s Christmas furlough. For his arrival, Menzies had the Atlanta rail station shot with a blue filter to throw the scene into a “wintery cold monotone,” punching up the rigors of life during wartime.*2 By contrast, the feeling of warmth was boosted for interiors at Aunt Pittypat’s house, creating a haven for Ashley and Melanie, one that follows them as they ascend the stairs with yellow-tinged candles, leaving Scarlett in a depression of heavy blacks and cold half-tones. For Ashley’s departure the following morning, Menzies wanted an absence of color, the gray uniform against the gray of the fog. “A very light blue filter helped this without really adding color,” he said.

By the end of March, Menzies was in Chico, ninety miles north of Sacramento, overseeing Gerald O’Hara’s riding scenes with director Chester Franklin and cameraman Wilfrid Cline. In scouting potential landscapes to represent Georgia and, in particular, the terrain opposite Tara, Menzies painted a vivid word picture of what he saw:

Rolling country in Spring green with plowed red fields, minimum amount of fences, and if possible some large oak trees, dogwood in bloom and pines in the distance. The action entails a ride of a horseman more or less across country, Negroes working in fields plowing and of course no indication of telegraph poles, paved roads, signs or houses, except buildings that might be outlying farm buildings.… This will be a shot showing the horseman riding so it will entail considerable area, possibly a 360° panorama.… Also required are shots of slave quarters, fruit orchards in bloom, shots of hill roads possible for use for Confederate troops coming home from war, also dramatic type of scenery among pines showing no plowed fields and apparently a good distance from any habitation. The principal requirement is very lush, rolling, peaceful countryside.

Little was peaceful, however, as there was no escaping Selznick. In a wire that found its way to Menzies in his compartment aboard the West Coast Limited, DOS complained of Lyle Wheeler’s rendering of Rhett Butler’s bedroom, which he described as “shockingly bad.” Given the importance of Rhett’s house to the second half of the story, he wondered if perhaps somebody else should be called in. In his reply, Menzies diffused the situation by offering his assessment of Major John Bidwell’s residence, built in Chico in 1865, and suggesting the mansion’s octagonal tower bedroom as a model for Rhett’s:

Menzies found opportunities for pattern in the fields of the antebellum South.

(DAVID O. SELZNICK COLLECTION, HARRY RANSOM CENTER)

OUTSIDE WINDOWS CAN BE SEEN BEAUTIFUL OAKS AND MAGNOLIAS AND OTHER WINGS OF HOUSE. MIGHT EVEN PLAY PART OF DAY OR NIGHT SCENES ON VERANDA AND NIGHT SCENES CAN BE LIT AND COMPOSED LIKE OLD ENGLISH CASTLE TOWER ROOM ESPECIALLY FOR DRAMATIC SCENES.

He sent some rough sketches to Wheeler, and Selznick embraced the idea to the extent that Rhett’s bedroom became similarly shaped, although he rejected the idea of windows on all sides as impractical. The eventual set was dominated instead by a huge full-figure portrait of Vivien Leigh.

April found Sidney Howard back at work on the script, but with low expectations and little time to spare. “I shall be finished early next week,” he advised his wife on April 8. “The problem arises then: when will [Selznick] read what I have written and clear me? I leave, of course, whether he clears me or not. Then he will put still another writer on my new script which he will not have read and the new man will spend another two weeks re-doing what has been done so often.” Selznick, he observed, was “bent double” with chronic indigestion and half the staff “look, talk, and behave as though they are on the verge of breakdowns.” Victor Fleming, having jumped without a break to GWTW from The Wizard of Oz, was particularly quick in showing the strain. “Fleming takes four shots of something a day to keep going, and another shot or so to fix him so he can sleep after the day’s stimulants.” Scarcely three weeks into Fleming’s time on the picture, actor Spencer Tracy visited the Flemings on a Sunday evening and stayed until midnight. “[I] thought I was nervous until I saw Victor,” Tracy wrote in his datebook. “Bad shape.”

Although he remembered him as “one of the few geniuses I ever met in the picture business,” Ridgeway “Reggie” Callow, second assistant director under Eric Stacey, could recall Menzies’ own distinctive coping routine: “For lunch he’d have five martinis and wouldn’t eat anything. Then at night he’d really start to drink. He had a friend [in] Jack Cosgrove.… He was a good sidekick. I’ll tell you, between the two of them we had a hell of a time getting them on the set, but once they were on the set they were pros.” Journalist Susan Myrick, an advisor on the “speech, manners, and customs of the period” and, like Wilbur Kurtz, an Atlantan, marveled at Menzies’ productivity. “Bill knows everything in the world about artistic effects,” she said in a column for the Macon Telegraph, “and does more work than any other ten men I ever saw. Yet he has time for a joke or a good story, often, and keeps us in gales of laughter with his Cockney-accent imitations and his tales of Scotland.… [His] set plans were so accurately scaled that an architect could trace his blueprints from them.”

Menzies had worked previously with Fleming, and the two men were, according to Laurence Irving, “old friends and partners” in the production of GWTW. “I spent many happy evenings with Bill at his home,” said Irving, who was visiting Los Angeles with producer Gabriel Pascal. “Tired as he was after a long day’s work, he was exhilarated by his complete fulfillment as a designer in his compositions for the immense canvas of Gone With the Wind that was now taking shape.”

Irving and Pascal spent time on Stage 14 at Selznick International, watching as Menzies arranged the towering nighttime shadows cast by Vivien Leigh and Olivia de Havilland against the far wall of a set, an effect he achieved with the use of doubles who were required to move in unison with the actresses in the foreground of the shot. “They were shooting the scenes in which Scarlett O’Hara was helping an old doctor in an improvised hospital in Atlanta. The set was a masterpiece—a wooden Presbyterian church, its east window shattered by shellfire, and before the altar a great field-stove was boiling water to sterilize dressings. The floor was carpeted with gray-clad and bandaged soldiers. Bill had rid himself of the restrictive supervision of Technicolor advisors, and, boldly experimenting, had made color his servant to enhance the dramatic impact of his camera setups. Every detail was perfectly contrived.”

On the set of GWTW, Laurence Irving bows to the master as producer Gabriel Pascal looks on. (KEVIN BROWNLOW)

As Menzies himself noted, the general lighting in the daytime sequence was white, yet “a rather poisonous blue & amber effect was thrown across the faces & beds to increase its unpleasantness. The source of this was indicated by using the usual blue & light amber window of the Victorian church.” In the vestry, which had been commandeered as an operating room, he underscored the “macabre effect” with an accent of green. “Remember,” Fleming called out to the extras, “this is a hot summer day. This hospital is a filthy place. You are tormented by wounds, mosquitoes, flies, bedbugs, lice. Now everybody sound off in misery … I want a perfect litany of pain!”

Six weeks into his tenure on Gone With the Wind, Victor Fleming was a physical and emotional wreck. On April 13, Monte Westmore, the unit makeup man, told Susan Myrick that Fleming couldn’t possibly last. “I think he is right,” Myrick recorded in her diary. “Vic told me today he was tired to death and he was getting the jitters and he thought he would just have to quit.” Selznick, who felt it would be “a miracle” if Fleming could shoot for another seven or eight weeks, proposed borrowing veteran director Robert Z. Leonard from M-G-M to act as understudy. Briefly, Fleming rallied, taking on the balance of Olivia de Havilland’s scenes and attempting to finish with Leslie Howard so that Howard could start work on Selznick’s Intermezzo. On Thursday, April 27, after a day of grappling with Melanie’s death scene, Fleming began shooting Scarlett’s frosty encounter with Belle Watling on the steps of the church.

Drained from the events of the day, Fleming would brook no dissension from Vivien Leigh, who had grown used to challenging him on their sometimes conflicting interpretations of character. Screenwriter John Lee Mahin, a close colleague of Fleming’s, was on the set and witnessed their clash. “Vic was feeling very ill,” Mahin said, “and he was nervous and tired. He had terrible pain in his kidneys; he had stones, and you could just see that he was drawn. She was getting more and more bitchy, because she was approaching the scene where she was an awful bitch, and she was getting scared of it.” Fleming ended the discussion by rolling up his copy of the script and suggesting that Leigh stick it up her “royal British ass.” Storming off the set, he vowed never to return.

The next day, it was announced that Fleming would rest a week, and that Sam Wood, late of M-G-M and Goodbye, Mr. Chips, would direct until his return. For Bill Menzies, the turn of events could not have been more momentous.

Samuel Grosvenor Wood was a renowned handler of actors, perhaps because he was once one himself. Born and reared in Philadelphia, Wood was the son of a textile manufacturer whose formal education scarcely extended beyond grade school. Tall and athletic, he went hunting for gold in Colorado and eventually landed in Los Angeles, where he fell into real estate. One night, he went to a dance at the Alexandria Hotel and met actress Clara Roush, a gorgeous redhead who also happened to be an heiress. She rebuffed him at first, thinking him beneath her, but Wood, with his piercing brown eyes, was such a handsome specimen she eventually agreed to go out with him. They were married in 1908, and their first daughter, Jeane, was born the following year.

Wood managed well for a while—he later reckoned he spent a decade in the investment game—then, as the proud owner of a cutaway coat, started taking day work in the movies after having “lost a fortune” in real estate. Cecil B. DeMille’s right-hand gal was Clara Wood’s best friend, and she was able to get Sam an interview with DeMille, who needed an assistant. “I’ll have you do everything,” DeMille told him, and eventually he was sent out to shoot some second unit footage. C.B. loved the results, and Wood, at age thirty-four, was advanced to assistant director, commencing with the marital comedy Old Wives for New. With DeMille’s blessing, Wood struck out on his own in 1920, directing the Wallace Reid comedy Double Speed. There followed a string of pictures for Famous Players-Lasky, a total of six with Reid and ten with Gloria Swanson, after whom Wood’s second daughter was named. By 1939, Sam Wood had more than fifty features to his credit, including such diverse fare as Peck’s Bad Boy, Christopher Bean, and A Night at the Opera.

Clark Gable wasn’t keen on Wood, having appeared under his direction in Hold Your Man, a good picture that unexpectedly turned into a showcase for Jean Harlow. Yet Wood quickly proved himself, jumping in on three days’ notice and nearly finishing with Leslie Howard, then shooting the Belle Watling scene that had brought the previous week’s schedule to a halt. Having never before directed a color picture, Wood was duly impressed with how Menzies achieved the night effects on the church steps using a heavy blue filter and a spray of blue light, leaving the strong patterns of color in the church’s stained glass windows to suggest the “warm spirit of relief” to be found within. “It was freezing cold that night,” Reggie Callow remembered, “and every time that Ona Munson as Belle Watling walked over to get into her carriage, the horses would decide to take a leak. They must have done it fourteen times, until their bladders finally ran out and we were able to get a good take.” Said Olivia de Havilland, “I liked that scene, and thought it went well, and was relieved to see that the new hand would guide us wisely.”

Menzies is photographed with Clark Gable and a somewhat distracted Vivien Leigh as they prepare to shoot Rhett and Scarlett’s escape from Atlanta. (DAVID O. SELZNICK COLLECTION, HARRY RANSOM CENTER)

Wood moved with remarkable speed, tackling the terrifically emotional scenes of Scarlett’s return to Tara, where she finds the house in shambles, nothing to eat, her sisters ill, and her mother dead. By midweek, even Gable had revised his opinion of Wood, pronouncing himself “very happy.” Gone With the Wind continued with Sam Wood at the helm for two weeks, Menzies stepping away to shoot inserts and compositional footage—generally things requiring doubles and not the principal actors—but otherwise remaining close at hand. When Victor Fleming returned on May 15, preparations were under way for what would become the picture’s most famous shot, in which Scarlett, in search of Dr. Meade, picks her way through a field of wounded soldiers, the camera pulling up and away until it reveals the full expanse of the Atlanta railway yards crowded with the bodies of hundreds, perhaps thousands, of Confederates.

The image came from a memorable passage in the book, Margaret Mitchell painting a vivid picture of men lying shoulder to shoulder in the pitiless sun, lining the tracks, the sidewalks, and stretching out in endless rows under the car shed.

Some lay stiff and still but many writhed under the hot sun, moaning. Everywhere, swarms of flies hovered over the men, crawling and buzzing in their faces, everywhere was blood, dirty bandages, groans, screamed curses of pain as stretcher bearers lifted men. The smell of sweat, of blood, of unwashed bodies, of excrement rose up in waves of blistering heat until the fetid stench almost nauseated her. The ambulance men hurrying here and there among the prostrate forms frequently stepped on wounded men, so thickly packed were the rows, and those trodden upon stared stolidly up, waiting their turn.

As it evolved, the shot was seen as encapsulating all the misfortune and misery that had befallen the South in its pursuit of war. In cinematic terms, the treatment was obvious; what wasn’t nearly so evident was how exactly to accomplish such a shot. Menzies had worked out the logistics in consultation with Lee Garmes, Jack Cosgrove, and Ray Klune. In March, just after Garmes’ dismissal, Selznick had written Cosgrove in connection with “the shot which you are going to do of the wounded men in the square, with the line of wounded extending beyond the actual bodies and dummies that we will be using, and with the tracks going off into the distance, I wish you would see the reference on page 292 of the book to the ‘rails shining in the sun.’ I wish you would go after this effect. I am also hopeful that Mr. Menzies will be able to contribute some ideas to Mr. Fleming for ways and means to get this effect of merciless sun and intolerable heat throughout this sequence.”

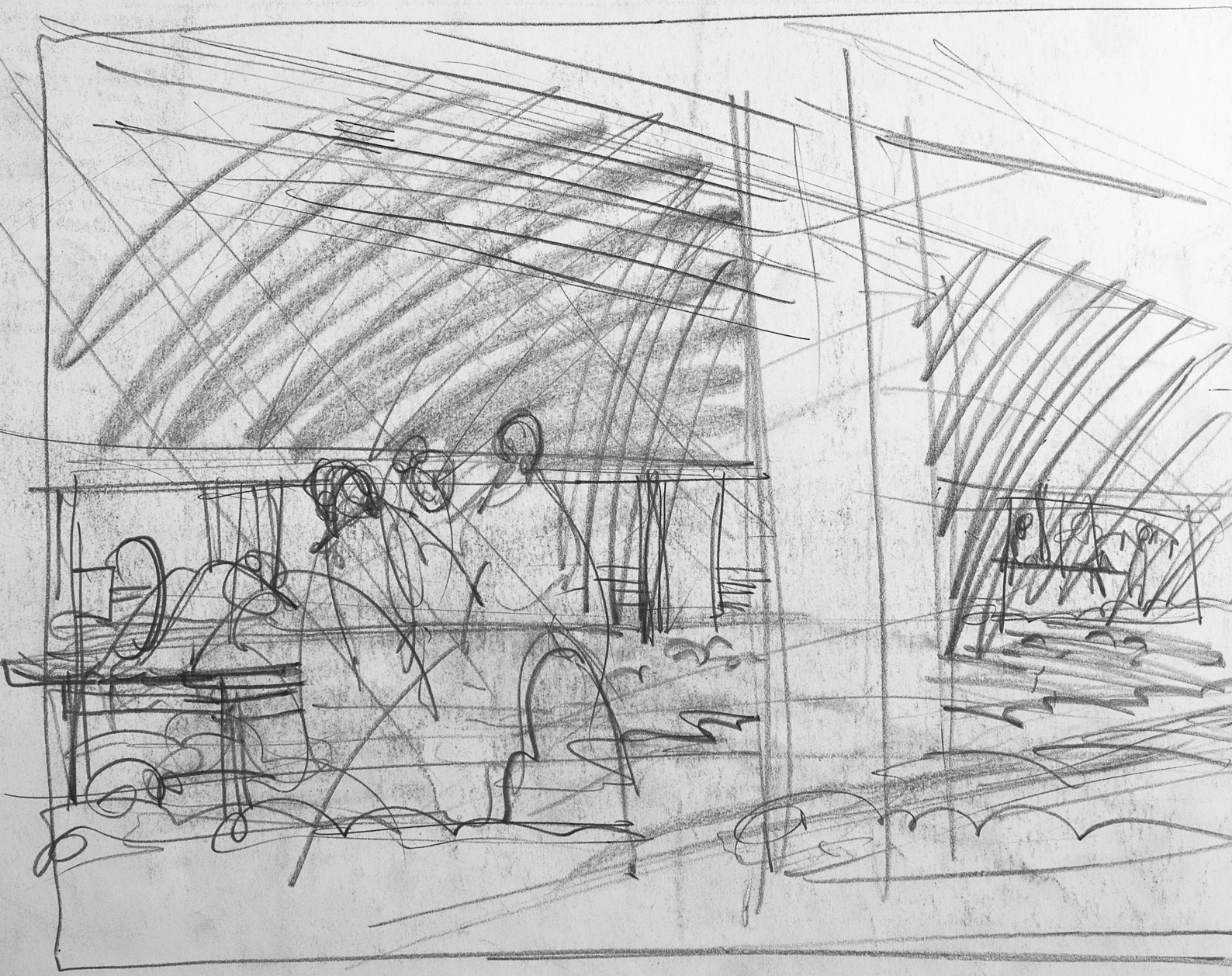

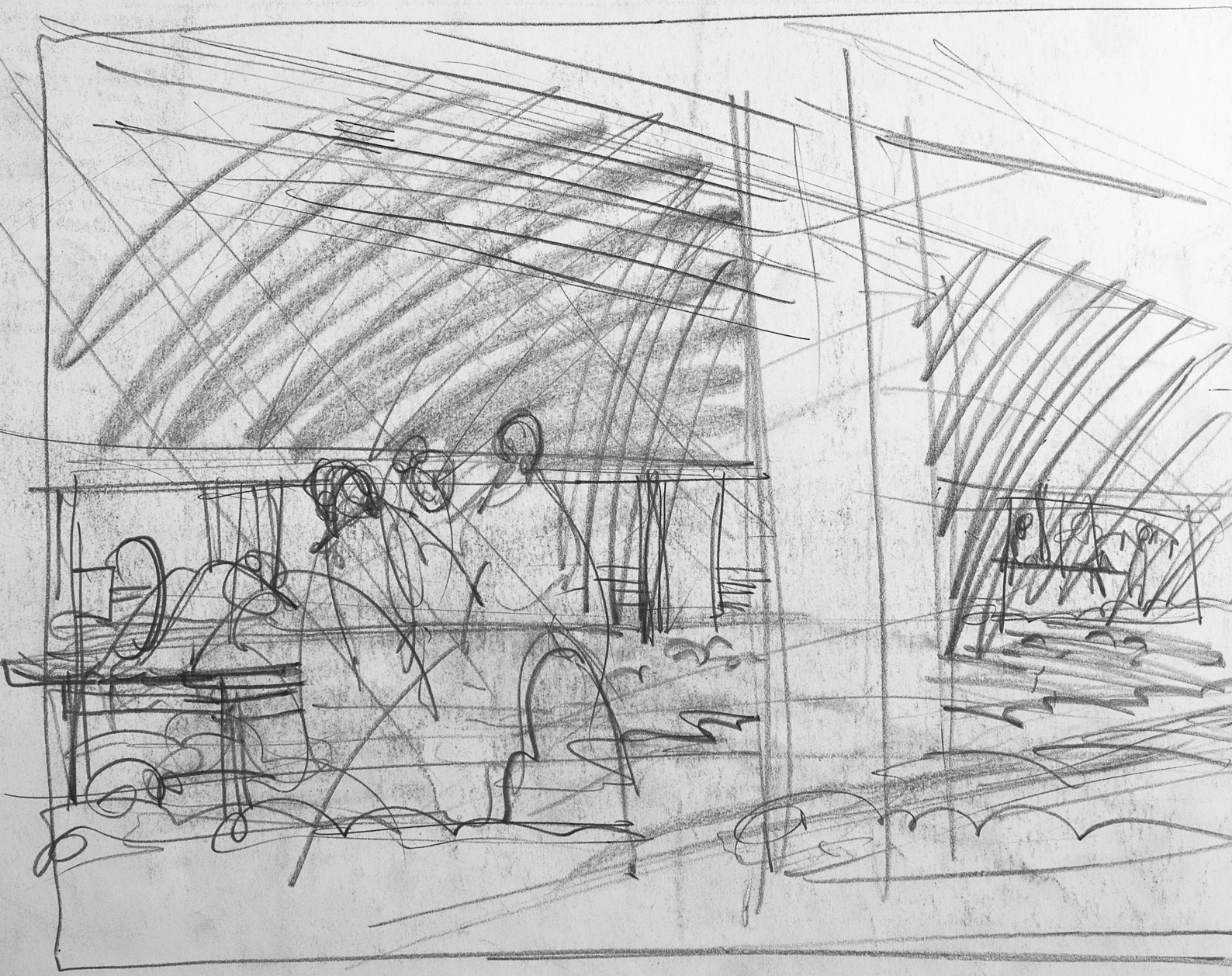

Menzies’ rough conception of the wounded crowding the Atlanta railway yards, working out the camera’s reveal of the dead and dying …

… as the scene progresses into the car barn. (MENZIES FAMILY COLLECTION)

Menzies’ sense was to try for “a brazen effect of sky” and a minimum of color in the pale gray uniforms of the wounded, the burnt red of the earth throwing the one bit of color—Scarlett’s hat—into prominence, emphasizing the tiny figure against “the massed carpet of wounded.” At first, it was thought that the shot could be made while Victor Fleming was away, but then Selznick made the decision to hold it for Fleming, knowing it would be one of the film’s signature images. “[Menzies] devised and created the shot,” Reggie Callow confirmed, “and it was his suggestion that we use an oil derrick crane in order to pull the camera back to such a high position.”

It had been estimated the camera would need to be approximately ninety feet off the ground at its highest point—far higher than for even the largest of camera cranes. Then there was the matter of vibration, a derrick crane hardly being a precision piece of photographic equipment. In the end, the problem was solved by placing the crane, with its tractor treads, on the back of a flatbed truck, thereby eliminating the need for the crane to move under its own power. Said Ray Klune, “We built a concrete ramp about one hundred and fifty feet long—it had to support a piece of steel that weighed ten tons—and these were the days before fast-drying concrete and we couldn’t put the damn crane on the ramp for two weeks, but when we finally did, we rehearsed it and the crane slid back down the ramp as smooth as glass while the arm raised and it worked out very smoothly.”

Work on the sequence began on Saturday, May 20, and continued on Monday, when Ernest Haller, operator Arthur Arling, and Fleming were sent aloft on a swinging eight-foot-by-eight-foot platform scarcely large enough to accommodate the bulky Technicolor camera. “A diesel engine pulled the truck that moved the crane,” Susan Myrick recounted for her Telegraph readers, “and as the long arm rose into the air the machine moved slowly backward, showing more and more rows of pitifully clad, crudely tended, wounded Confederates. I had a feeling that the cameraman was about as high as [Atlanta’s seventeen-story] Candler Building.” Said Clarence Slifer, “The studio used all of the extras that the Guild could supply for wounded soldiers, about 1,500 of them, and added about 1,000 dummies.… When our shot was finished at 11:30, the assistant directors called ‘lunch.’ It was like God passed his healing hand over the wounded, for 1,500 soldiers leaped to their feet and ran for the lunch wagons.”

With Fleming back, Selznick was eager to speed up the picture, anticipating as many as five units working simultaneously. Fleming was “more than agreeable” to having Sam Wood set up a unit “for shooting nights or Sundays or any other time,” with Vivien Leigh splitting her time between the two. “I think that Hal Kern should spend practically his entire time on the set,” Selznick said, “figuring out ways and means of cooking up suggestions and of gathering them from Menzies and myself, etc., to substitute simple angles that do not take [the] time [needed] for elaborate angles, where these elaborate angles are not materially helpful to the scene.… I think also that it is important that Vic be more precise about setting the exact first setup for the next morning. On this, too, I think he might feel better if Hal were with him and if Hal could send for Menzies—but only when and where he thought this would be an advantage. To me there is no reason for changing setups in the morning except on the rarest occasions.”

Selznick, writing deep into the night, was himself often responsible for last-minute shifts in scheduling. “There were days when we didn’t even know what we were doing tomorrow,” Ray Klune said. “It was not at all uncommon for David to call me at three in the morning and ask me what we were shooting tomorrow. I’d say, ‘David, you’ve got the schedule right there on your desk, so I know that you know.’ He’d say, ‘Can we change it?’ I’d say, ‘At this time of the morning?’ This happened time and time again.”

On May 23, the company decamped to Lasky Mesa in Agoura, an hour’s drive northwest of Culver City, where, between dawn and sunrise, they would attempt, once again, Scarlett’s famous vow to “never be hungry again.” The setting was the vegetable garden at postwar Tara, but clouds had hidden the rising sun on at least four previous occasions. “We made ten attempts before we shot that scene as Mr. Selznick had visualized it,” Menzies recalled. “We always had to gamble with the weather. It was necessary to be on location by 2:30 o’clock in the morning. Nine times we were thrown into despair. Waiting for just the right moment, we would be greeted by fog, mist, rain, or a cold blank sky. On our tenth try, the sun rose as Scarlett kneeled on the ground. The clouds formed about her in one of the most beautiful compositions I have ever seen. It was as though a kind Providence looked down to give us suddenly and generously this remarkable moment.”

As Fleming continued to work with the principals, Menzies directed stunt doubles and Cosgrove shots. He made portions of Scarlett and Rhett’s escape from Atlanta, filming evenings and weekends, and was seemingly on twenty-four-hour call to Selznick, whose Benzedrine habit kept him going eighteen hours a day. “Mother used to say, ‘When you’re going to school, he’s coming home from work,’ ” Suzanne Menzies remembered. “So he’d come home early in the morning because he’d been working all night. I never saw him. Once in a while he’d come home for dinner. Or he’d come home, and at two in the morning he’d get a phone call from Selznick to come up to the house. That happened a lot.”

Reggie Callow could recall a time when Selznick called Menzies to a seven o’clock meeting in his office and then showed up at nine. “Then,” said Callow, “his butler brought his dinner at nine or nine-fifteen. Menzies said, ‘I’m going across to the Coral Isle,’ which is a Chinese restaurant opposite the studio, and we all went over there. At eight-thirty the phone rang and a secretary said that Mr. Selznick was waiting for us, so we made him wait another half hour while we finished our dinner, and then we went over.” On Sunday, May 28, Susan Myrick wrote in a confidential letter to Margaret Mitchell: “The whole company is so damn tired of the picture they are ready to cut each other’s throats at any moment.”

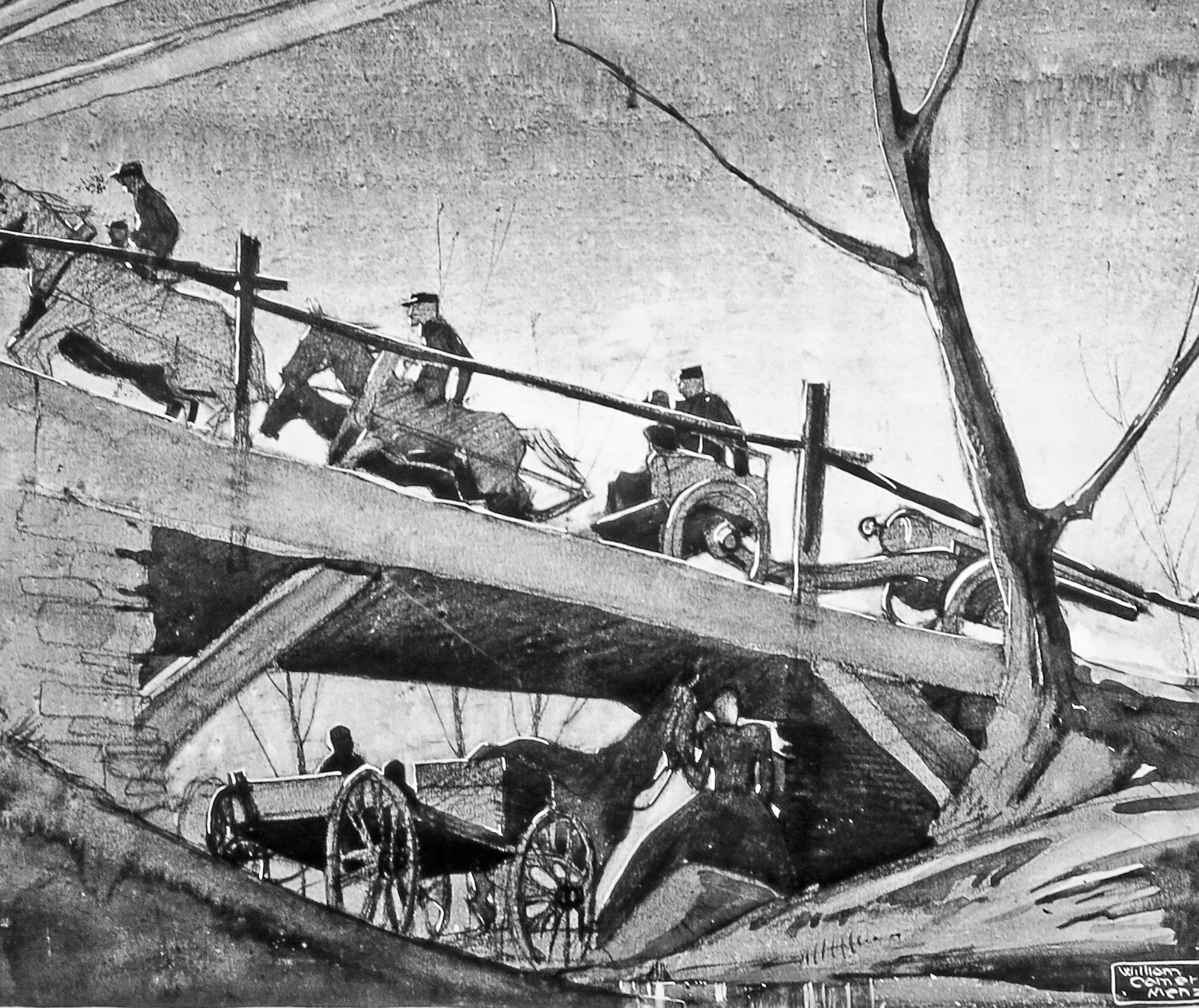

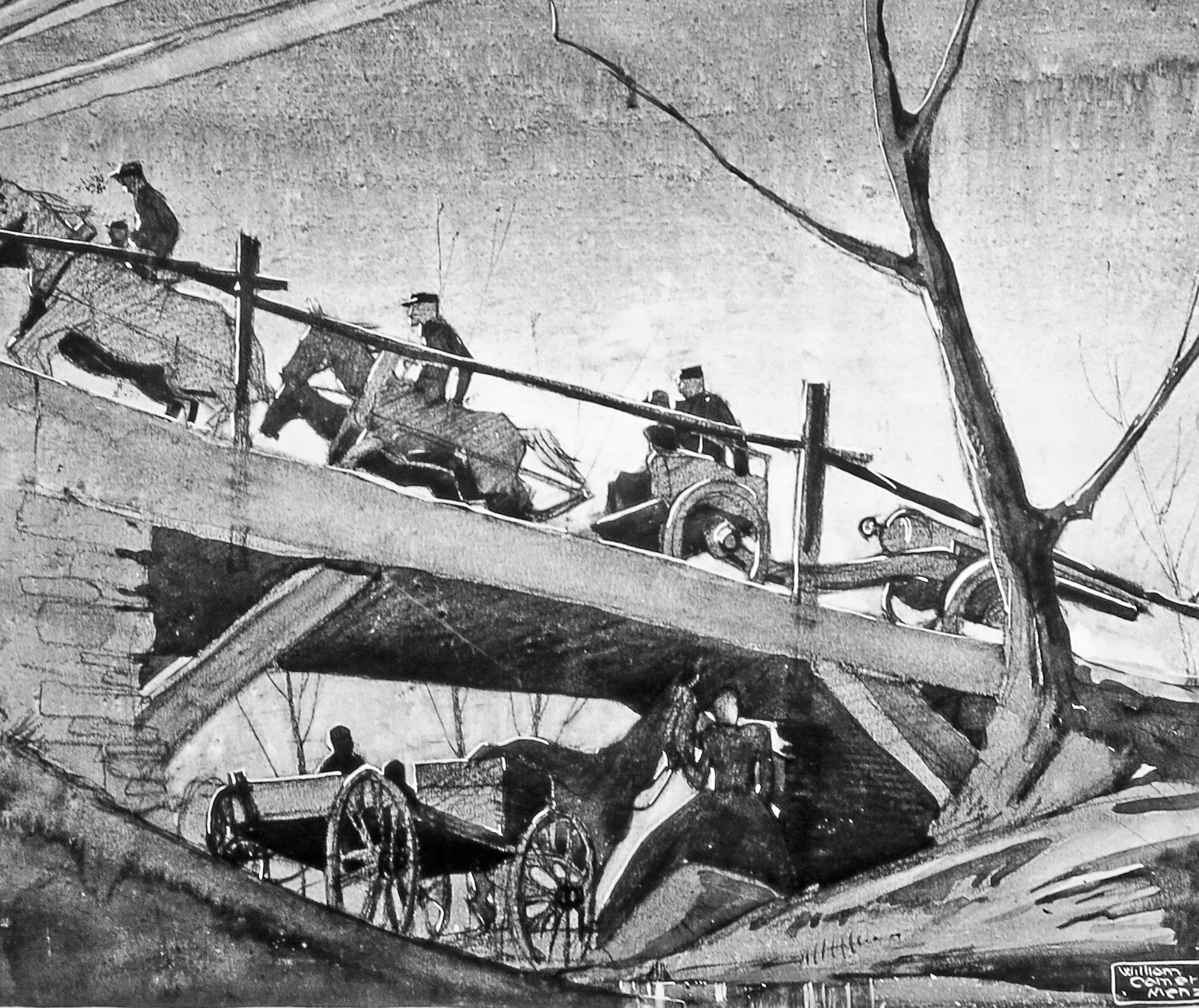

With Yankee artillery approaching, Scarlett leads the horse and wagon bearing her charges into a ravine …

Sam Wood returned on May 29, directing an exterior with Olivia de Havilland while Fleming completed Clark Gable’s drunken monologue on Stage 11. Reggie Callow broke off, going with Wood and Menzies, while Eric Stacey remained with Fleming. “We now had three units working,” wrote Clarence Slifer. “Bill Menzies had these sequences so well laid out that when the scenes were cut together there were no differences in visual effects or continuity between them.” Wood, who lacked Fleming’s compositional eye, was enchanted with Menzies’ color drawings—especially his little continuity sketches (which Menzies himself likened to those of Constantin Guys, a French watercolorist and illustrator whose work he admired). Never before had Wood encountered the technique of pre-visualizing a sequence, shot for shot, and was grateful for the help. As Callow suggested, “I think [Bill] felt that Sam Wood needed him more than Fleming. Menzies was a big help to everybody; he was great for morale. Everybody loved Bill and I think he loved everybody, too. Really, he did, because he’d come around and be fun and laughing all the time.”

… where they hide in the shadows until the danger has passed. Menzies’ gifts as an illustrator invest these moments with a sense of drama few art directors could have achieved. (DAVID O. SELZNICK COLLECTION, HARRY RANSOM CENTER)

Menzies was still doing second unit work of his own when he turned his attentions to packaging matters such as the opening titles, which he felt should presage the gathering winds of war. In a memo to Selznick, he described what they were developing in sketch form: “The Main Titles will be a series of southern landscapes with skies which should by their continued darkening give an increasingly threatening aspect to the scene.… The last sky is shattered by an explosion disclosing Sumter with an equally dramatic sky. Dissolve from this to an American flag being pulled down through the smoke and the Southern flag being raised.… After the cut of the Southern flag we could dissolve back to a long shot of Sumter burning and in the smoke an indication of the clash of arms and the Yankee horde, but so dim that no actual forms are visible.” He proposed scrubbing the troublesome opening with Scarlett and the Tarleton Twins, beginning instead with the “quittin’ bell” and Gerald’s ride toward Tara, the small figure of Scarlett approaching to meet him, Mammy, in close-up, leaning out the window and imploring her to come back for her shawl.

Nearly six months into production, even Selznick was forced to acknowledge the toll Gone With the Wind had taken on practically everyone. “Quite apart from the cost factor,” he admitted, “everybody’s nerves are getting on the ragged edge and God only knows what will happen if we don’t get this damn thing finished.” On the morning of June 27, 1939, Menzies returned to Lasky Mesa and directed the pullback on doubles for Gerald and Scarlett that would provide the silhouetted figures for the revised “love of the land” shot. Then Scarlett’s double, Joan Rodgers, changed into another dress for the film’s climactic shot, another pullback, in which Scarlett, having watched Rhett walk out of her life, returns home to Tara to think of “some way to get him back,” refusing to be defeated, declaring, “After all, tomorrow is another day!”

And back in Culver City, Fleming was finishing with Vivien Leigh, her last scene being Gable’s departure into the night, her tearful pleading, “If you go, where shall I go, what shall I do?” bringing the immortal response, “Frankly, my dear, I don’t give a damn.”