14

Something Quite Bold

On June 22, 1939, as Gone With the Wind was in its final days of principal photography, David Selznick dispatched a cable to Alexander Korda:

WE HAVE SPENT SEVERAL MILLION DOLLARS EDUCATING MENZIES IN TECHNICOLOR SO I DO NOT BLAME YOU FOR WANTING HIM STOP PLEASE CABLE IMMEDIATELY LATEST DATE YOU COULD USE HIM AND WILL TRY TO WORK IT OUT STOP BELIEVE THERE IS EXCELLENT CHANCE CAN ACCOMMODATE YOU FOR THIS ONE PICTURE

Having lost control of London Film, Korda had gained the approval of his partners at United Artists to form a new company, Alexander Korda Film Productions, with initial financing of $1.8 million. The “one picture” to which Selznick referred was a new Thief of Bagdad that would bring to bear all the technical advances that had come to the screen in the sixteen years since the Fairbanks original. Korda envisioned a fantasy informed—if not necessarily inspired—by original music, and had hired the Russian-born composer Mischa Spoliansky to create themes and songs for the film. Then, in Korda’s whimsical way, Spoliansky was supplanted by Miklós Rózsa, who had memorably scored the producer’s last London Film production, The Four Feathers. Similarly, Korda engaged Ludwig Berger to direct the picture. Berger, whose stage credits included collaborations with Max Reinhardt, had the notion that music should drive the action in The Thief of Bagdad, and in place of Rózsa insisted upon Oscar Straus, whose Les Trois Valses he had filmed in France the previous year.*1

Straus, more than twice Rózsa’s age, proved unacceptable, delivering, in Rózsa’s judgment, “turn-of-the-century Viennese candy-floss” wholly inappropriate to the tone of an Arabian Nights adventure. Rózsa was reinstated as the film’s composer, but Berger could never master the spirit of Lajos Bíró’s adaptation. Filming began on June 9, 1939, with Berger having the actors play their scenes in time with an audio playback. It was, observed Rózsa, as if they were expected to move like dancers in a pantomime. “They just couldn’t get it right, and after a week’s work we had practically nothing to show.”

Korda stepped in, working alongside Berger, and soon Michael Powell, the thirty-three-year-old director of The Spy in Black, was off shooting footage in Cornwall with the film’s fifteen-year-old star, the Indian-born actor Sabu Dastagir. “Listen,” Korda said to Powell, “Ludwig Berger is going to do the directing but I’m convinced that we will not have finished this summer before the war breaks out; do you want to join the team and produce the sequences that I ask of you?” Known for his quota quickies, Powell was apparently an interim choice, for when Selznick agreed to loan Bill Menzies to the man who held Vivien Leigh’s contract, it was not merely to design the picture but to actually direct it—an announcement that got headline play in The New York Times. That same day, Louella Parsons led her column with the words: “History repeats itself in the case of William Cameron Menzies …”

Selznick fixed a release date of July 5, affording himself ten more days of Menzies’ time if Sundays and Independence Day were observed, and as many as thirteen days were he to be worked constantly. Early on, Menzies had urged that they “go as far as possible with the blood and suffering, even to the point of having the doctor blood-spattered and operating on or tending a wound which is just out of the scene.” Now Selznick worried that Menzies would “shoot battlefield shots that will be so gruesome as to be censurable.” He arranged for story editor Val Lewton to go out on location with him so as to suggest alternate takes where appropriate. “For instance, there should be one shot in which the pool is not colored red with the blood of dead men. On the other hand, to repeat, I want to be sure Menzies makes at least one take as he thinks it should be.”

Menzies’ final week on GWTW was filled mostly with the shooting of inserts—the red earth in Scarlett’s hand, the pulling of a radish from the ground, the twin graves of Ellen and Gerald O’Hara. There were shots of letters, posters, a bank draft for $300. In early July, a rough cut of the film, still missing certain effects and lacking its opening credits, was shown, quite possibly for the first time ever, at an approximate length of four and a half hours. “It was very spooky,” Suzanne Menzies remembered. “We went to the back gate at Selznick, they unlocked it, and there were only a few lights around. We were taken into a screening room, and Hal Kern, the cutter, was there with another man. Daddy was sitting, talking to them through the whole thing, giving his input, because Daddy was going to go to England in a couple of days and they wanted him to see the movie. It was basically finished. It didn’t have a score, and it had big scenes missing, but it had a continuity of sorts. We were told not to tell anybody that we had seen it; I think we saw it before even Selznick saw it. Of course, the next day it was: ‘Guess what I saw last night!’ ”

There were still a lot of rough edges to the picture, but for being so long, Gone With the Wind had a symphonic unity born of graphic integrity. The golden patina of its opening minutes and their idyllic views of the Old South gave way to the pastel clarity of the scenes at Twelve Oaks. With news of the Gettysburg battle casualties—“hushed and grim”—came the cold dominance of blues and grays. Sherman’s shelling of Atlanta stirred the red dust in the streets, casting, as Menzies saw it, a “more effective pall” than had it been yellow or buff. The siege brought a quickening of the tempo and, with Butler’s arrival at Miss Pittypat’s, a suggestion of the rail yard fire that reduced the palette to great masses of red and black. Outside town, the glare was accentuated with orange filters and cool highlights, and, at the ruins of Twelve Oaks, the sky was a liver color with magenta overlays that followed through to Tara and the break for intermission.

Menzies, his younger daughter recalled, liked the first half, up to where Scarlett vowed never to be hungry again. “That’s where he said they should have ended it. He hated the second half. He thought it was unnecessary.” The completed film represented a total of 137 shooting days for the first unit, 93 of which could be credited to Victor Fleming, 24 to Sam Wood, and 18 to George Cukor. Retakes and added scenes amounted to 24 days, and second unit work—much of which could be credited to Menzies—accounted for another 33 days. By the time the film was completely finished, total footage used on Gone With the Wind would approach half a million feet of film.

On July 5, his final day on the picture, Menzies took five-year-old Cammie King to M-G-M to film the beginning of Bonnie Blue Butler’s fatal pony ride, doubles, their backs to the camera, appearing as Rhett and Scarlett. The next day, July 6, he left for New York via rail as papers around the country carried the news of his new assignment. Six days later, on July 12, 1939, he sailed for England and his third tour of duty with Alexander Korda.

When Menzies arrived at Denham, he found there were already three units at work on The Thief of Bagdad: The original Berger unit, now effectively being run by Korda himself, Michael Powell’s unit, responsible, in Powell’s words, for “a certain number of very visual and decorative scenes like the arrival of a boat, all those wide-eyed shots,” and a special effects unit headed by his pal Larry Butler, who was shooting the flying horse sequences on a blue ramp erected in West Hyde. To make matters worse, Menzies found England much closer to war than he had originally thought. “Already the rattling of arms was getting louder and sandbags were appearing all over the place,” he said. “One of the first unpleasant things to appear in the studio was a directional sign which read: WALKING CASUALTIES THIS WAY.”

Apologetically, Korda explained his predicament and grandly offered Menzies the title of associate producer. Vincent Korda had already designed all the sets; although the film owed much to the Fairbanks version, there was little of the towering majesty that had distinguished the original. “When he first saw Vincent’s huge set,” Michael Korda wrote of his uncle Alex, “he turned away in disgust and said, ‘Tear it down, build it twice the size and paint it red.’*2 Now there was some doubt it could be built at all, despite the fact that a great deal of money had been invested in the film.”

Instead of involving him with the sets or the overall design of the movie, Korda asked Menzies to direct the film’s many trick photography sequences, which, he pointed out, were bound to be seen as highlights. Menzies, of course, had been present at the creation of a great many Technicolor effects for Gone With the Wind, but here he would be working with Butler’s “traveling matte” technique of combining two color images into one composite shot. Given that there were multiple film elements to register, the results were bound to be imperfect, and a blue outline could often be seen surrounding the figures inserted into the action.

“The machine shops at Denham were swell,” Butler said. “These chaps were fine craftsmen and wonderful machinists. In converting optical printers used for black and white work to color we had to develop a lot of gadgets and many problems had to be overcome.” The people from Technicolor advised against it, at one point threatening to have Butler taken off the picture. But the advantage of fluid movement outweighed the technical drawbacks, and the effects accomplished for the first time in The Thief of Bagdad would set the standard for blue screen composites for decades to come.

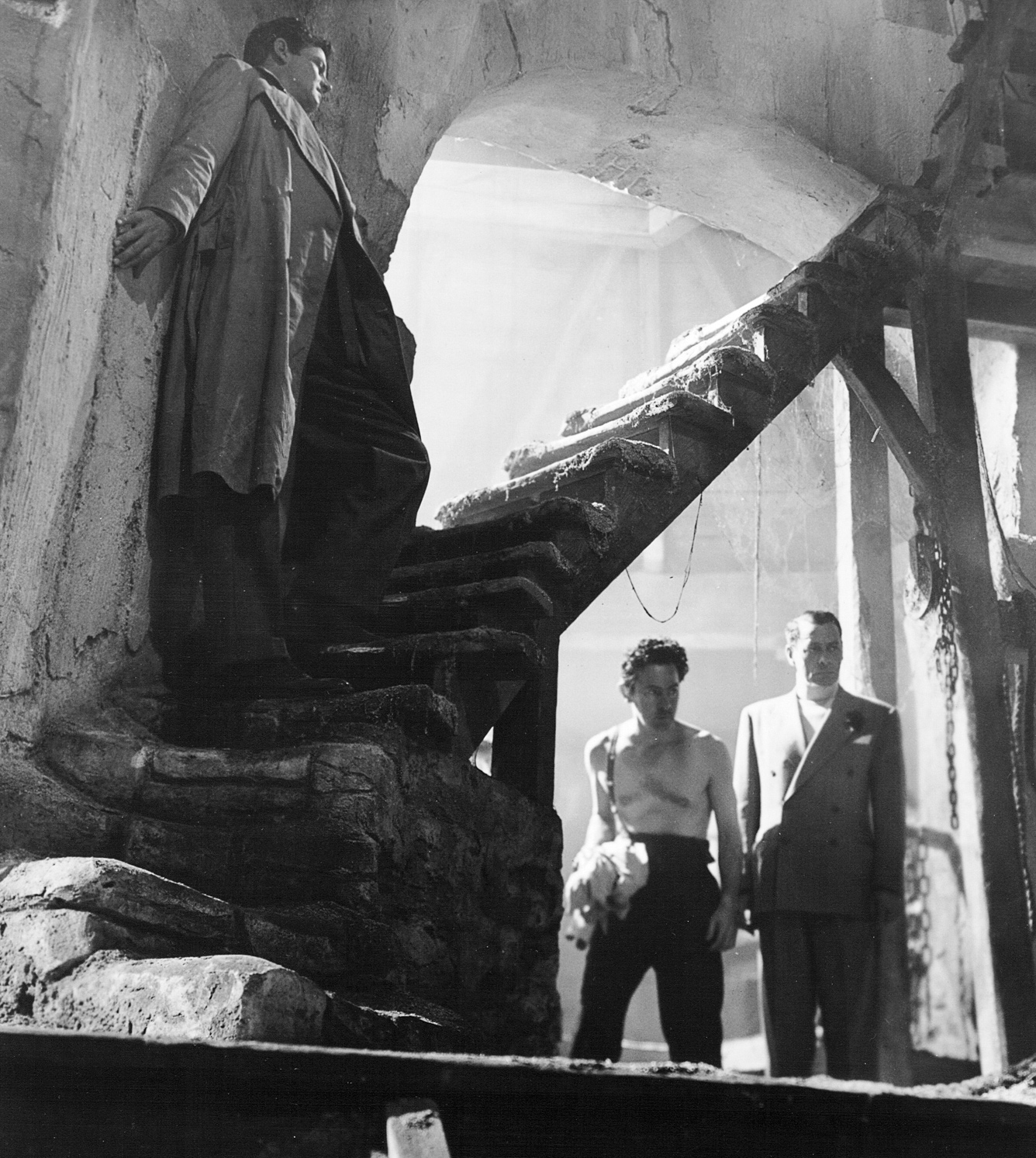

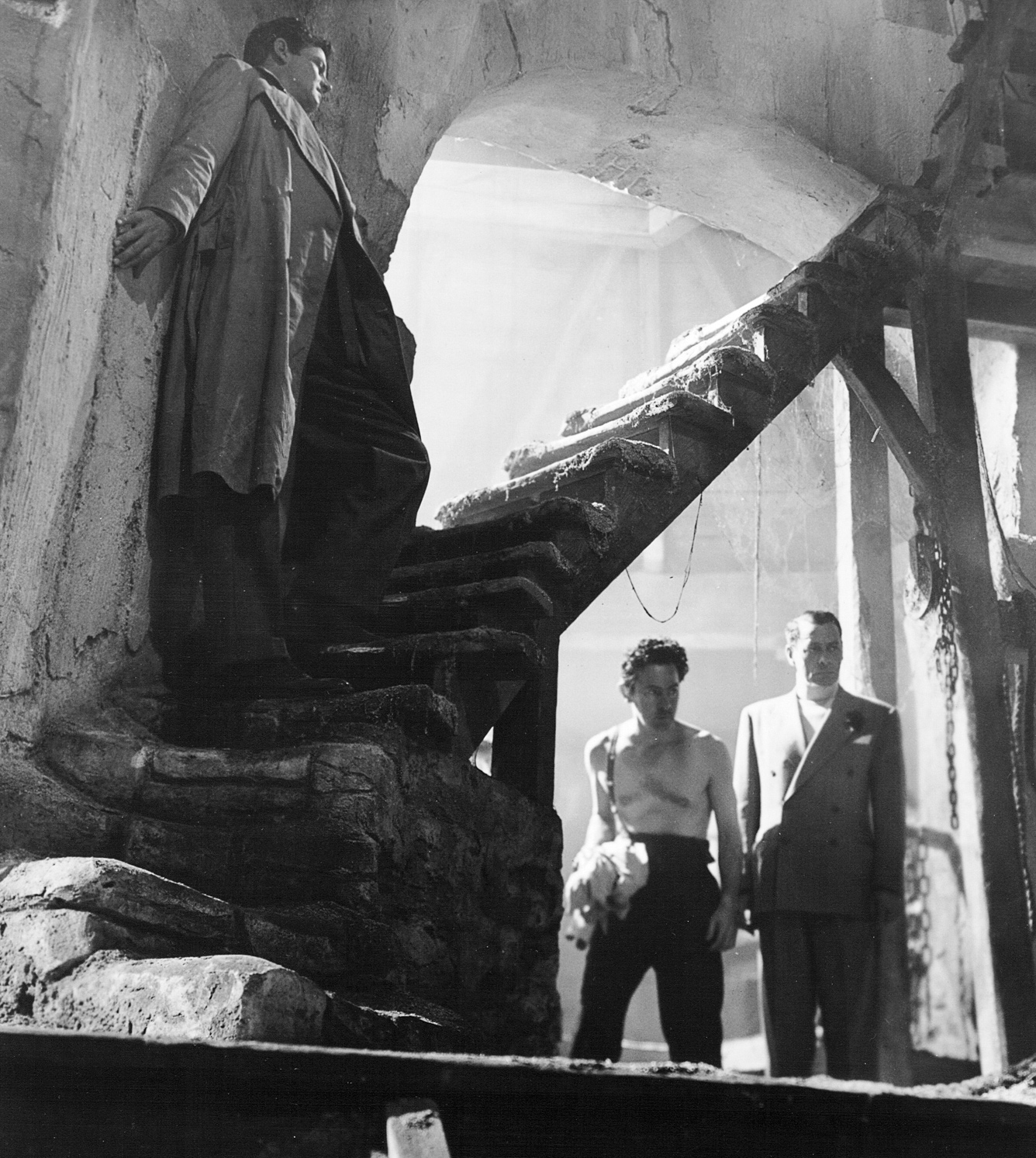

Menzies’ contributions to The Thief of Bagdad (1940) were limited chiefly to directing the special effects shots featuring Rex Ingram and Sabu. He had no influence on the overall look of the film, which was designed by Vincent Korda. (AUTHOR’S COLLECTION)

The new Thief would contain modern interpretations of memorable events from the silent version, such as where the thief, Abu, must steal the all-seeing eye from the Goddess of Light. “The fantastic scene of Sabu trying to climb the huge idol and filch the magic eye was all double-printing,” Menzies noted, “as the idol was a miniature, not much larger than Sabu. So the idol was shot first, and the figure of Sabu, in attitudes of climbing, printed over the scenes.” The giant face of the idol was fabricated for shots of Sabu at the summit, some of which were angled downward to emphasize the peril, the rest of the statue being a matte painting executed by Denham’s Percy Day. The effect on-screen was extraordinary, indeed one of the highlights of the picture.

On August 18, one month into Menzies’ tenure on the film, Ludwig Berger was tactfully dismissed after nearly sixty days of production. Korda replaced him with Tim Whelan, an American who had just finished directing Laurence Olivier and Ralph Richardson in a spy melodrama called Q Planes. “Tim Whelan especially specialized in action sequences,” Michael Powell explained. “I don’t know for sure who filmed what.” With four directors on the project—three officially—Korda seemed to be taking a page from the Selznick playbook. “Korda was technically the producer,” said actor John Justin, who was making his film debut as the dashing Ahmad, “but he controlled the film totally and, effectively, directed it.”

In March, Britain had declared its support for Poland in the aftermath of Germany’s invasion of Czechoslovakia, and now that reckoning was at hand. On September 1, Germany attacked Poland on its western, southern, and northern borders, drawing a joint ultimatum from the United Kingdom and France to withdraw its troops. Concurrently, there was a general mobilization of British armed forces. Remembered Menzies: “On Saturday, September 2, 1939, I was working with 300 Hindu extras. On the fatal Sunday [when war was declared] I was sleeping in when my assistant came over (I was living opposite the studio) and said that Korda wanted us to shoot as the weather was good. As I walked through the gate, which was thoroughly sandbagged and a First Aid station, the air raid siren went off about five feet from my head. The War was on—and I turned bright gray. The Hindus all got in the air raid shelters, so I went back home and stood in the front door waiting for the pyrotechnics.”

The air assault never materialized, but Korda, at the request of Winston Churchill, commandeered many of those working on Thief of Bagdad and turned their talents and resources to the making of a low-budget morale booster that was in cinemas scarcely eight weeks later. “The Sunday when the war broke out, we were still in the middle of filming,” said Michael Powell. “And the next day, a Monday, I was already in a bomber filming The Lion Has Wings, the first movie about the war.” Menzies remained with Thief, but managed to get a cable off to Mignon in California:

AWAITING DEVELOPMENTS EVERYTHING STILL OKAY

DON’T WORRY LOVE=

An item in The Hollywood Reporter had the cast and crew working in gas masks, which the actors removed when making a shot. By the end of the month, Menzies was on location in Wales, filming the initial scenes between Abu and Djinn—played by the distinguished black actor Rex Ingram—on a mile-long stretch of yellow sand at Tenby, Pembrokeshire, remaking material Powell had earlier attempted under the cramped conditions of Sennen Cove.

“The conversation Sabu has with the giant djinni, who towers over him on the sands of the beach, presented a problem in close-ups which we had not anticipated,” Menzies said. “In going from one to the other in close-up, it was impossible to tell that the djinni was a giant and Sabu just a lad, as both faces were the same size on the screen. We solved the problem by showing Sabu’s head at the bottom of the screen, leaving plenty of head room, thus giving the impression that he was small, while the giant’s face filled the screen. Simple suggestion you may say, but not so simple when you encounter the problem for the first time.” Menzies later told his daughter Suzie that they were stuck in Wales a good long time. “Evidently,” said Suzie, “very few people had ever seen a black man in that part of the world in that era. He was beautiful and had that booming voice. Little kids would follow Rex down the village streets and point at him, and he thought it was very funny and marvelous. They called him a Blackamoor.”

Menzies stuck it out until the picture was finished, sending occasional wires home assuring his family that he was well and okay. On October 9, it appeared he would be leaving in ten to fourteen days. “At that time there were very few Americans left,” he said, “and it looked as if it was going to be pretty tough to get out.” Finally, on October 23, he set sail for New York aboard the Dutch liner Statendam, which was blacked out and crawling with “mostly amusing and fairly unscrupulous” adventurers. “It was still scary,” said Suzie. “It was full of diamond merchants from Antwerp.”

In Menzies’ absence, Selznick had pared Gone With the Wind to a running time of three hours and forty minutes, a reduction of nearly fifty minutes off the version screened for Menzies in July. To bridge the gaps, he commissioned seven titles from Ben Hecht, and when Menzies arrived back in New York on October 27, the picture was in the process of being scored by Max Steiner. Selznick’s mind, however, was as much on Rebecca as it was on GWTW, that film, based on Daphne du Maurier’s best-selling novel, having gone before the cameras the previous month.

“I question that we are ever going to get as good an effect for the opening and closing of Rebecca—the scenes involving Manderley—as we might have had if Bill Menzies had worked on them,” he wrote Ray Klune on October 23. “Since Bill will be back in town shortly, if you can get him in for a few days, or even a week, to work on these two scenes I think it would be more than worthwhile, and I urge that you do so.” Menzies consulted on Rebecca over a period of three months, directing shots of Manderley in ruins and, in one instance, planning out a crucial sequence. Working very much on a piecemeal basis, his efforts would go uncredited on the finished film.

Far more important to Menzies’ professional future, given that things “looked a bit dreary,” was the film version of Thornton Wilder’s Pulitzer Prize–winning play Our Town, the rights to which had been acquired for $75,000 by independent producer Sol Lesser. Initially, Lesser had wanted to make the picture in color with Ernst Lubitsch directing. Then William Wyler was supposedly borrowed from Goldwyn for the job, an arrangement that lasted exactly one week. Finally, in November 1939, Sam Wood was engaged, a curious choice at first, given the play’s minimalist staging, which proved far too integral to ignore. Whether or not Wood was instrumental in bringing Menzies onto the project is uncertain; in a letter to Laurence Irving, Menzies implied he had sought the assignment out on his own, knowing that adapting the play to film would be an interesting challenge. Happily, Lesser was committed to doing a proper job of it and had enlisted the close cooperation of the playwright.

The staging conventions for the play dated from The Happy Journey to Trenton and Camden, an earlier one-act that established some of the themes Wilder would explore more fully in Our Town. Four kitchen chairs were used to represent an automobile, carrying a family of four some seventy miles. When Our Town made its first appearance in 1937, there was no curtain, no scenery. The Stage Manager entered, placing a table and three chairs downstage left, and a like grouping downstage right. Eventually, ladders and a small bench were added, nothing more. The film would need to be similarly stylized for the material to play properly. Yet, shooting the movie on a bare stage would be off-putting to a mass audience, likely dooming it to the art circuit normally reserved to foreign language pictures.

“The play, when I saw it, impressed and delighted me,” wrote Lesser. “I was determined to make the film as faithful as I could. But if I had not taken the precaution of asking Thornton Wilder to assist with the script and accept the powers of veto on the production, I am sure that, in spite of all my good intentions, Our Town would not have proved half so successful, either as a transcription of a play or as a motion picture.”

Lesser retained a stage designer named Harry Horner to consider the problem, only to conclude that Horner knew nothing of film technique. Yet when Menzies came aboard, he reviewed Horner’s work and thought he had some very practicable ideas. A Czech immigrant, Horner was related by marriage to Lesser’s daughter, Marjorie. “I found this accent on props without the use of scenery such an interesting device,” Horner said, “and such an interesting elimination of all that crap that is called scenery, that I thought we should do that in the film.… I thought it would be interesting to have only these props, let us say the soda fountain, in focus and the two people close to it, but the rest out of focus.” Horner’s concept would permit the realistic settings demanded of commercial motion pictures while minimizing their significance. “[Menzies] thought that the idea was marvelous, etc., etc., and though he was now engaged, this famous man insisted that he would share his credit with me, which was an extremely kind thing.” Horner would soon return to Broadway, where Reunion in New York and Lady in the Dark awaited him.

Lesser’s draft screenplay was the product of a collaboration between the producer and actor-playwright Frank Craven, who had created the role of the Stage Manager in Jed Harris’ landmark production. Lesser, who carried on a lively correspondence with Thornton Wilder, had already considered—and rejected—a number of stylistic devices, including Wilder’s own suggestion of opening the film on a jigsaw puzzle “setting the background against the whole United States, that constant allusion to larger dimensions of time and place, which is one of the principal elements of the play.” Lesser’s own opening, with Craven’s Mr. Morgan appearing at the door of his drugstore and saying, “Well, folks, we’re in Grover’s Corners, New Hampshire …” seemed, in Wilder’s judgment, “far less persuasive and useful” and was similarly nixed.

Menzies crafted a layout for an entirely different opening. Contained in the final shooting script of January 9, 1940, it drew its inspiration from the play, where the Stage Manager speaks the names of the author, the producer, the director, and the various cast members up front. He proposed no opening titles, just the lone image of Craven approaching the camera:

EXT. HILLTOP (NIGHT)

SILHOUETTE

On top of hill, in silhouette against the star-studded sky, are two parallel split-rail fences, the area between the fences forming what is presumably a cow-run. Over the scene is heard:

SOUND

(MAN WHISTLING)

After a moment a man’s head, also in silhouette, appears over the brow of hill directly beyond the far fence of cow-run. The man (MR. MORGAN—FRANK CRAVEN) comes fully into view as he reaches far fence.

Lots of detail—comes upon scarecrow, adjusts hat, breaks off a small bough and trims it to use as a walking stick, passes behind tree, illumination of struck match, lights pipe, comes to a rustic bridge, replaces broken rail in fence, tastes a nut, leans on the top rail of a pasture gate where, from a side angle, the 1940 town can be seen.

There was concern over the introduction of Simon Stimson, the troubled church organist of Our Town (1940). In this conceptual drawing, Stimson is discovered during choir practice, the action framed by a circular church window that places all emphasis on the little man in the foreground. (MENZIES FAMILY COLLECTION)

Craven says his opening lines (“same names as around here today”), then says, “Oh, yes, now for the benefit of those that feel they should have titles …” He fumbles in his inside pocket for six sheets of paper, on which he has lettered the credits in Spenserian script. He comments on each sheet. (“These are the people that are going to take part in the picture. Guess you know pretty near all of ’em.”) On the sheet that would include Menzies’ credit, he says, “Whew! Takes a lot of people to make a picture.” On the director’s credit he says, “You all know who he is.”

Prior to Menzies’ arrival, Wilder had expressed concern that some scenes, if more realistically portrayed than onstage, would lose their novelty. In the play, for example, the wedding scene was followed through normally, a rarity in pictures. In the theatre, its novelty came from the economy of its settings, the Stage Manager assuming the role of the minister, and the “thinking aloud” passages afforded the characters—all qualities lost in the screenplay. “This treatment seems to me to be in danger of dwindling to the conventional,” the author said in reaction to an early draft. “And for a story that is so generalized that’s a great danger. The play interested because every few minutes there was a new bold effect in presentation methods. For the movie, it may be an audience-risk to be bold (thinking of the 40 millions) but I think with this story it’s still a greater risk to be conventional.”

When fabricated, Menzies had the hub of the window enlarged so that actor Philip Wood would be contained within it, the vectors pointing in at him from all sides. A focus of town gossips, Stimson is a marked man who will drink himself into an early grave. (AUTHOR’S COLLECTION)

Considering the problem, Menzies decided the idea of throwing the backgrounds out of focus would work for a few individual scenes—the soda fountain exchange between George and Emily, for instance, which was played with a plank and two chairs onstage—but would get monotonous if overused. Stylistically, his natural bent was to resort to close-ups and two-shots—which were typically used sparingly in American films—to give the characters prominence while deemphasizing the backgrounds. Virginia Wright, drama editor of the Los Angeles Daily News, followed the preproduction phase in her column “Cinematters,” eager to know how Lesser would meet the challenge of making Wilder’s poetic little drama into “something more than just a series of episodes in small town life.” He solved the problem, Wright concluded, by engaging Menzies as production designer.

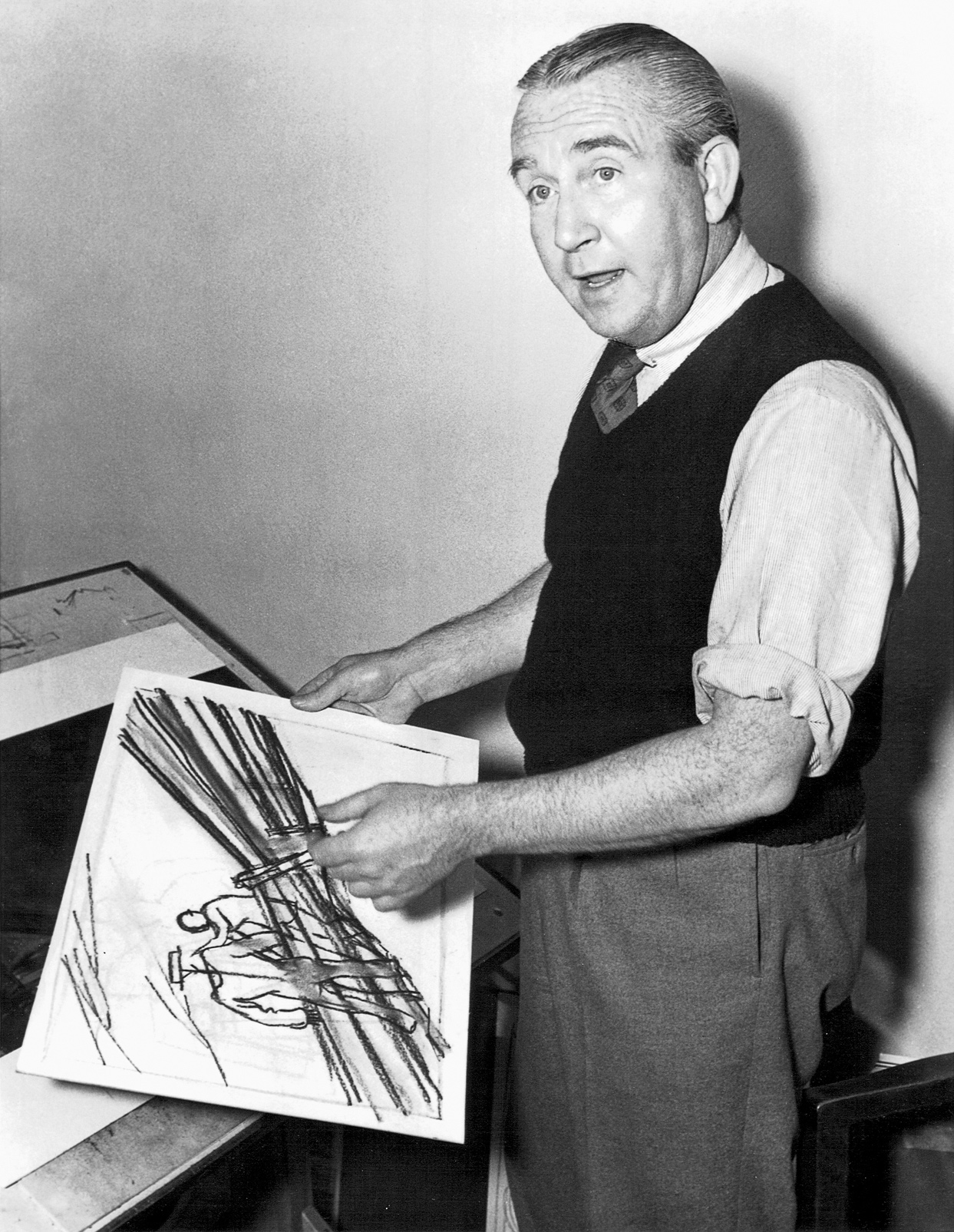

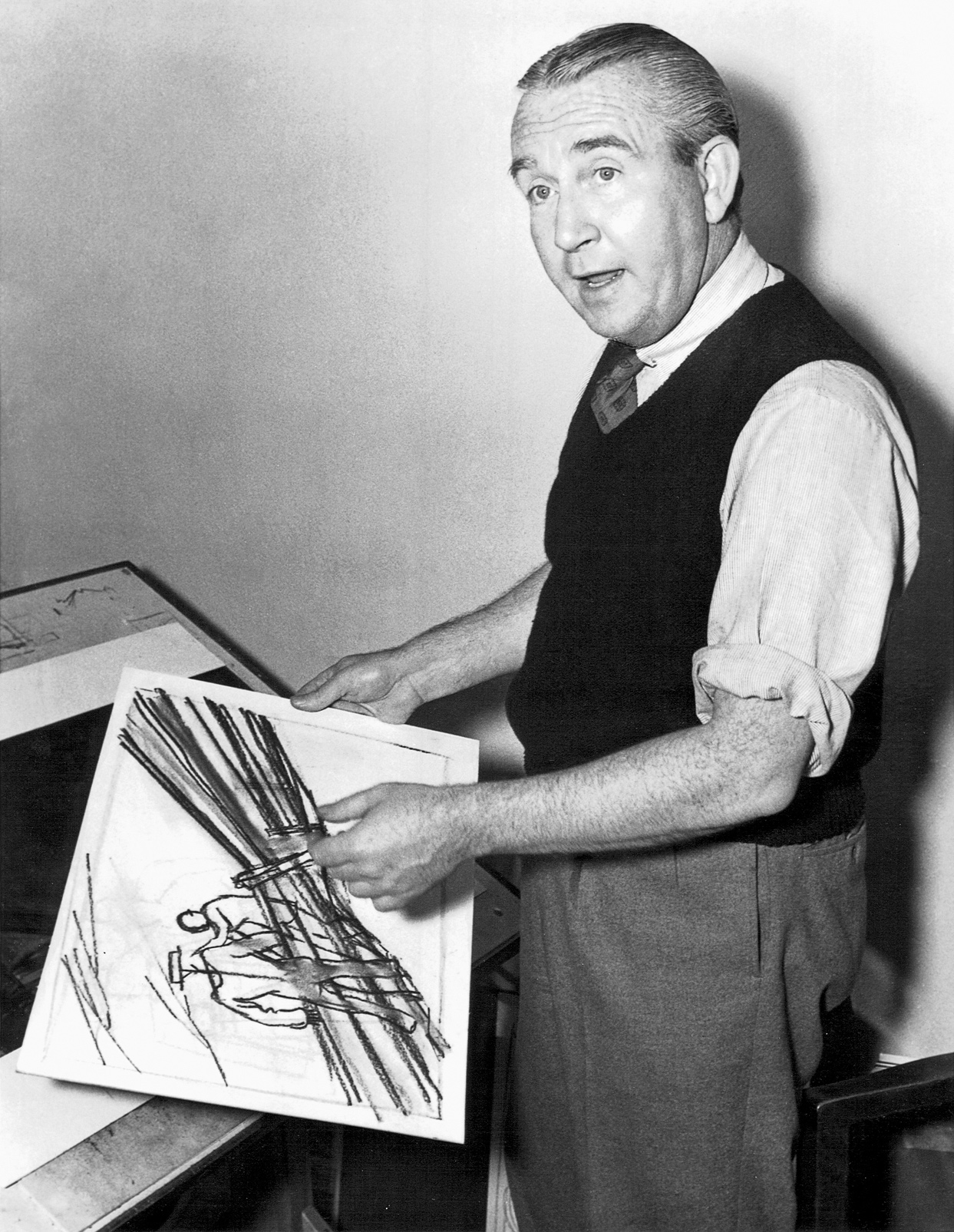

The day we called on Menzies, who, incidentally, is one of the most articulate men in Hollywood, he was just beginning the graveyard sequence and was as excited as a dramatist on the brink of his play’s big scene. He has a host of ideas, using gauzes to diffuse the backgrounds and concentrate the eye on the umbrellas and figures in the foreground. All this has to be worked out with Sam Wood, the director.… Once they’ve agreed on the sketches, Menzies turns them over to Mac Johnson, his renderer, and to art director Lewis Rachmil, who in turn passes [these] out to Bert Glennon, the cameraman, and to the head electrician. On the basis of what he’s already done, Our Town is destined to be something extraordinary on the screen.

In a letter to Wilder, Lesser described their overall approach, offering some specific examples:

The picture itself will be treated in an unconventional manner with regard to camera set-ups, following our original idea of introducing properties intended to accentuate the moods and visualize something deeper than just the mere dialogue. For instance, in the [drunken church organist] Simon Stimson episodes, with the scenes played in moonlight, the photography will accentuate the black and white shadows. The little white New England houses, which look so lovely in other shots, will look naked and almost ghostly in relation to Simon Stimson, to whom they did not offer nice lovely homes but a cold world that ruined him.

As a further example, when we come to Mrs. Gibbs on the morning of the wedding, we will see her through the kitchen window grinding the coffee, but in the foreground the flower pots will be dripping in the rain to accentuate the general mood, so that Mrs. Gibbs is almost a secondary element in this scene. And just as another example: When [George’s sister] Rebecca is crying in her room the morning of the wedding, we see her little pig bank tied by a ribbon to a corner of the bed, which will remind the audience of what Rebecca likes most in the world. I think this little effect will give as much to an audience as if we had a whole scene about her.

The ladies of the choir gossip after practice. In composing even this simple scene, Menzies deliberately broke the rules of conventional staging. The camera is placed lower in the frame, cutting into Mrs. Soames’ hat. Occupying the center of the shot, actress Doro Merande speaks her lines with her back to the camera. Fay Bainter, Merande, and Beulah Bondi work in close, their nighttime surroundings vanishing in the intimacy of their exchange. (AUTHOR’S COLLECTION)

In sending Wilder a copy of the final shooting script, Lesser, who was used to producing westerns, Bobby Breen musicals, and an occasional Tarzan picture, could scarcely contain himself. “I can’t commence to tell you my enthusiasm for the sketches that have so far been prepared. They are indeed artistic, and I think we will get a very unusual result.” Filming began at the Goldwyn studios on January 17, 1940. Forming the principal cast was a splendid array of character people: Fay Bainter, Beulah Bondi, Thomas Mitchell, Guy Kibbee, Stu Erwin. Playing George Gibbs, a role filled in New York by Frank Craven’s son, was twenty-one-year-old William Holden, fresh from his success as Joe Bonaparte in Golden Boy. From the original Broadway production came Doro Merande, Arthur Allen, Craven, of course, and actress Martha Scott, who created the role of Emily Webb in the Jed Harris production and had originally come to Los Angeles to test for the part of Melanie in Gone With the Wind. (She was told at the time that she wasn’t photogenic.) With the beginning of the picture not yet settled, Lesser and Wood chose to open production with the cemetery scene, which was played in New York against the bare wall of the stage with twelve chairs representing the graves of the townspeople.

Emily’s graveyard exchange with Mother Gibbs, played with actress Fay Bainter in the foreground and Martha Scott in the middle distance. “In the play, the dead mother and friends sat on chairs and talked to her,” Menzies said, pondering the problem before the start of filming, “but I have to have them in graves, and having graves talk is very dangerous. A laugh at the wrong time would ruin the picture.”

Menzies had designed the entire sequence, closing in on the characters to the point of cutting off an actor’s head in one particularly tight grouping. Wood objected, as such a composition would violate every principle of staging he had come to embrace. “Mr. Wood wanted the whole head,” Lesser recalled. “[Mr. Menzies] maintained that this would ruin the shot. I settled that one by suggesting it be done the way the art director*3 wanted—if necessary, it was a very easy scene to do over again. Wood agreed reluctantly. After he saw it, he was convinced that they were getting a style which was completely Bill Menzies’ and he never set up again without calling for Menzies to approve.”

At the end of that first day, Lesser wrote Wilder yet again:

You are going to get a real thrill, Thornton, when you see on the screen the production of the graveyard sequence as designed by Mr. Menzies. There is great inspiration from the time the mourners under their umbrellas come into the graveyard. We never show the ground—every shot is just above the ground—never a coffin nor an open grave—it is all done by attitudes, poses, and movements—and in long shots. The utter dejection of Dr. Gibbs—we have his clothes weighted down with lead weights so they sag—the composition of Dr. Gibbs at the tombstone is most artistic—and as Dr. Gibbs leaves the cemetery the cloud in the sky gradually lifts, revealing stars against the horizon—and as the cemetery itself darkens, a reflection from the stars strikes a corner of the tombstone which is still wet from the recent rain, and the reflection (halation) seems to give a star-like quality—and the scene gradually goes to complete darkness. We get a vast expanse of what seems to be sky and stars. When this dissolves to the dead people this same reflection of halation appears to touch the brows of the dead. It is lovely—something quite bold!

Menzies liked to employ a wide angle lens for deep focus shots, saying that doing so amounted to a long shot and a close-up at the same time. For Emily’s graveyard exchange with Mother Gibbs, actress Fay Bainter’s head and shoulders were to fill the immediate foreground, while Martha Scott would stand full figure in the background. No lens was fast enough to hold both characters in focus under such subdued lighting conditions, so it fell to Bert Glennon to achieve the composition with a split screen. In tackling the scenes of Emily in death, revisiting the morning of her sixteenth birthday, Menzies eschewed the common device of the apparition, a double exposure yielding a transparent figure on screen. Instead, the shot was made as normal, then Scott was filmed against a black velvet background, clad in a white dress and flooded with light. A traveling matte was made, enabling the two images to be married in the lab. The result was more in keeping with the play, an Emily more substantial than ghostlike.

Sam Wood told Martha Scott that if she was in films for fifty years, she’d never have anything more difficult to do than those scenes corresponding to the last act of the play. “I had no one to talk with,” Scott said. “I had to be by myself with little black markers as people and then they put that on the film.” Wood, she added, seemed “uncertain” about a play that was at times so impressionistic. “He had the production stage manager, Ed Goodnow, with whom I worked and who was Jed’s man, there to help him. He said to the company, ‘Listen, Ed is our man. He knows the workings of this play, he knows the timing, he can help me with cutting it and making it into something as wonderful as the play.’ So that helped Sam tremendously. He was a wonderful man.”

The West Coast premiere of Gone With the Wind took place on December 28, 1939, at L.A.’s Carthay Circle, following gala openings in Atlanta and New York City. Ten thousand spectators lined the streets, all straining to catch glimpses of Clark Gable, Carole Lombard, and “an audience of Hollywood celebrities that surpassed any other that has ever gathered together for a premiere.” Searchlights were stationed along San Vicente Boulevard for a block on either side of the theater. Menzies, now deep into preparations for Our Town, attended with Mignon, occupying a pair of orchestra seats valued at $11. It was the first time either had seen the completed film with score and titles, yet all the eliminations and polish did nothing to alter Menzies’ initial assessment of the picture: it still should have ended at the break.

There was, of course, talk of a sweep at the Academy Awards, the picture having garnered outstanding reviews, and therein lay a particular challenge to the winner of the first Oscar for Art Direction—William Cameron Menzies was no longer an art director. Having pioneered the concept of production design, and being virtually its only practitioner, Menzies had no category into which he could neatly fit. As matters stood, Lyle Wheeler, with whom Selznick had grown increasingly frustrated, was a sure bet for a nomination and an odds-on favorite to win. Selznick sensed this injustice as acutely as anyone, and while he worked to get Menzies nominated for a special award for GWTW, he feared that such efforts “would probably increase interest in him, and may boomerang on us in our desire to sign him.” This would be doubly true, he acknowledged, should Menzies actually get such an award. “I have made up my mind that when I start producing again there is one man I definitely want and that is Bill,” he said in a January memo to Daniel O’Shea, “so I am counting definitely on your working out a deal, and as soon as possible, along the lines we discussed.”

Selznick touched on the subject of Menzies in a lengthy letter to Frank Capra, first vice president of the Academy and president of the Screen Directors Guild. “Bill Menzies,” he wrote, “spent perhaps a year of his life in laying out camera angles, lighting effects, and other important directorial contributions to Gone With the Wind, a large number of which are in the picture just as he designed them a year before Vic Fleming came on the film. In addition, there are a large number of scenes which he personally directed, including a most important part of the spectacle. Day and night, Sundays and holidays, Menzies devoted himself to devising effects in this picture for which he will never be adequately credited.”

When the nominations came down on February 11, 1940, Wheeler was indeed in the running, one of a record thirteen nominations accorded the film. Menzies, on the other hand, wasn’t mentioned at all. Not that he had been completely ignored by the Academy in the years following his historic 1929 win for The Dove and Tempest; in 1930, Academy records show that he was under consideration for his work on Alibi and The Awakening, and in 1931 for his design of Bulldog Drummond. The committee that nominated and voted the award was comprised of art directors and alternates from all the major studios—men who knew and, in many cases, revered Menzies’ work. So when the awards were bestowed at the Ambassador Hotel on the night of February 29, 1940, GWTW’s eight wins were augmented by a special plaque that bore the following words:

TO WILLIAM CAMERON MENZIES

FOR OUTSTANDING ACHIEVEMENT IN THE USE OF COLOR

FOR THE ENHANCEMENT OF DRAMATIC MOOD

IN THE PRODUCTION OF “GONE WITH THE WIND.”

As the filming of Our Town progressed, the matter of a proper opening for the picture remained a vexing issue. Thornton Wilder hadn’t liked Menzies’ idea of hand-lettered credits, and as production got under way, they still hadn’t found what Sol Lesser referred to as an “emotional reason” for beginning the story back in 1901. “Everyone seems to feel that the opening should have a feeling of air, broadness, and scope,” Lesser said, “rather than being confined in a set or in front of a store, but we can’t put our fingers on it.” In the end, they had it all along, as what they settled on was essentially Menzies’ opening with the titles superimposed over Frank Craven’s leisurely approach.

In his notes for Gone With the Wind, Menzies wrote of painting fences “dead black for dramatic pattern.” Now, he opened on the weathered patterns formed by a pair of split rail fences, allowing them to cross the top third of the screen in silhouette as the film’s title occupies the morning darkness beneath. While the credits flash, the distant figure of Mr. Morgan approaches, negotiating a loosened plank and then ambling along the pathway, the camera following as he pauses to adjust the hat on a forgotten scarecrow. An old oak tree passes into view as he lights a pipe and proceeds along the pathway to a wooden bridge, where he hammers a railing back into place with a river stone. At the other side of the bank, the path juts sharply toward the camera, the figure coming into detail as Sam Wood’s name fills the screen. He nods a greeting. “The name of our town is Grover’s Corners, New Hampshire,” he begins. “It’s just across the line from Massachusetts. Latitude is forty-two degrees, forty minutes. Longitude is seventy degrees, thirty-seven minutes.”

In considering the opening of Our Town, Menzies opted for strong diagonal pattern in the form of the split rail fence that leads Mr. Morgan, the narrator, to a Grover’s Corners of an earlier time. (ACADEMY OF MOTION PICTURE ARTS AND SCIENCES)

In one eloquently stylized two-minute shot, Menzies was able to establish the time of day, a sense of place for the town known as Grover’s Corners, and tell the audience everything it needed to know about Mr. Morgan, the narrator—all while dispensing with the credits, and all without benefit of dialogue. (“The new opening’s fine,” Thornton Wilder acknowledged, with obvious relief, in a letter to Sol Lesser. “I shudder at the way you spare no expense, fences, bridges, nut-trees, distant villages, scarecrows—! It’s fine.”) It was, everyone seemed to agree, the screen equivalent to the look of the play, a gloriously artificial panorama, exquisite in its selective detail, the sort of visual economy necessary to distill a beloved three-act play into a running time of about ninety minutes. Displaying the distant image of the modern-day Grover’s Corners on a rear projection screen, Morgan says, “First we’ll show you a day in our town—not as it is today in the year nineteen-hundred and forty, but as it used to be in the year nineteen-hundred and one.” He signals the operator, and a quick shift of images returns the scene to an earlier day. The story is off and running in little more than three minutes.

On film, the artificiality of the opening was mitigated by the easy authority of Frank Craven, whom Brooks Atkinson called “the best pipe and pants-pocket actor in the business.” (AUTHOR’S COLLECTION)

Menzies was considered so essential to the making of Our Town that his drinking became a source of tension, especially for Sam Wood, who depended on him so thoroughly. “I was the assistant director on the show,” said Lee Sholem, “but my biggest job was to keep him off the booze, or, to keep him off it at least long enough for him to get the job done, and then let him go out and have his drinks.”

By the third week in February, the company was finishing up with various cast members and looking toward a close of production sometime in early March. “Everyone—not only the ‘Yes Men’—yes, everyone is most enthusiastic,” Lesser said at the time, “and I think we have something quite different in novelty, both from the photographic and storytelling standpoint. Now if the motion picture public wants this kind of a story—all is well.”

The credited art director, Lewis Rachmil, consults a continuity board during the filming of Our Town. Director Sam Wood and Menzies look on. (MENZIES FAMILY COLLECTION)

In the year 1963, Alfred Hitchcock was questioned by an earnest young interviewer who said that he presumed that all of Hitchcock’s films were “pre-designed by an art director.” Did he, in fact, do all the drawings himself?

“Well,” said Hitchcock, “art director is not a correct term.

You see, an art director, as we know it in the studios, is a man who designs a set. The art director seems to leave the set before it’s dressed and a new man comes on the set called the set dresser. Now, there is another function which goes a little further beyond the art director and is almost in a different realm. That is the production designer. Now, a production designer is a man usually who designs angles and sometimes production ideas. Treatment of action. There used to be a man … is he still alive? William Cameron Menzies. No, he’s not. Well, I had William Cameron Menzies on a picture called Foreign Correspondent and he would take a sequence, you see, and by a series of sketches indicate camera setups. Now this is, in a way, nothing to do with art direction. The art director is set designing. Production design is definitely taking a sequence and laying it out in sketches.

With the completion of Rebecca, Selznick closed his studio for an extended period, ultimately liquidating Selznick International in order to draw down the substantial profits generated by Gone With the Wind. He began selling off the properties he owned—The Keys of the Kingdom and Claudia, among others—and loaning his contract talent to other producers. Vivien Leigh and Ingrid Bergman were sent to M-G-M while his one director, Hitchcock, was lent to producer Walter Wanger. The deal with Wanger was concluded on October 2, 1939, establishing Hitchcock as the director of Vincent Sheean’s memoir Personal History, a property that had been under development since 1935.

Considering the book dated and unsuited to his particular strengths as a storyteller, Hitchcock, in collaboration with his wife, Alma Reville, and his secretary, Joan Harrison, devised an entirely new plotline which carried Sheean’s title from the book and little else. Eventually, the title, too, would be dropped, the film instead drawing its name from Sheean’s longtime profession—Foreign Correspondent. By the time Menzies came aboard in March, reportedly at Hitchcock’s behest, a total of twenty-two writers had contributed to the script, including John Howard Lawson, Budd Schulberg, John Meehan, James Hilton, Ben Hecht, and Robert Benchley. Indeed, Selznick may have had a hand in putting the two men together, as Hitchcock had never before tackled a picture as big or as complex. Selznick was also keen to establish a demand for his British import, whose last released picture in the United States was Jamaica Inn—a dud.

Menzies found that Hitchcock, himself a former art director, was in the habit of making rough pencil sketches on his copy of the script. Menzies, in turn, worked out more than a hundred oversized drawings of sets and action for the start of production, as well as models of a dozen sets. When shooting began on March 18, 1940, the film was already four months behind schedule and progress was, at times, agonizingly slow. Menzies later recalled “a rather unpleasant association with Hitch” that nevertheless yielded “some pretty good results.” Among the principal sequences was a plane crash staged in the same manner as the dirigible crash in The Lottery Bride. “I hardly used any miniatures at all,” said Menzies, “but did the whole thing objectively, that is from a point of view always inside the cabin. I also had a very interesting sequence in a windmill where we really got some good photographic effects, and an assassination sequence in Amsterdam in the rain, which I rather borrowed from Our Town.”

For Emily’s funeral procession, Menzies took the convention of the black umbrellas from the landmark stage production of Our Town and arranged the shot so as to obscure the faces and forms of the individual mourners, the composition conveying its emotional impact in the stark commonality of grief. (MENZIES FAMILY COLLECTION)

The huddle of black umbrellas to represent Emily’s funeral cortege was a memorable feature of Jed Harris’ original stage production, and Menzies had elaborated on it, gathering the canopies, glistening in the rainfall, in the foreground of the shot and allowing the night sky to fully occupy the upper half of the frame. There had never been a more spiritual composition for the talking screen, and now Menzies took the same basic elements, expanded their numbers exponentially to fill a public square, and clustered them to emphasize the particularly brazen murder of a Dutch diplomat, an event that sends John Jones in pursuit of the killer, an adventure similar in substance and pacing to the director’s earlier 39 Steps.*4

Menzies freely admitted appropriating the umbrellas for the assassination scene in Foreign Correspondent (1940), the jostling of the black canopies effectively tracking the killer’s path of escape. (AUTHOR’S COLLECTION)

The windmill scenes were shot during the first days of production and afforded a kinetic maze of hazards and hiding places, the actors confined to a claustrophobic tangle of stairways and gears, the protagonist (Joel McCrea) eluding Nazi agents while attempting to rescue the drugged and disoriented Van Meer, whose memory holds the critical clause of an allied peace treaty. Menzies estimated he made “about 200 drawings” for Foreign Correspondent, roughly a quarter of the number he typically did for a feature, implying he worked primarily on the film’s complex set pieces.

Menzies’ work on the windmill sequence, the core of which he described as a “spiraling disclosure of a light-knifed stairway,” represents a seamless collaboration with supervising art director Alexander Golitzen and his associate Richard “Dick” Irvine, who were charged with the progressive refinement of the set as the continuity evolved. (AUTHOR’S COLLECTION)

“It was my observation,” said actress Laraine Day, “that Mr. Hitchcock and Mr. Menzies conferred on every shot that had been drawn by Mr. Menzies. Whether or not there was a storyboard for the entire production, I don’t really know, but it would seem reasonable to believe that if every scene was drawn before it was filmed, there must have been a storyboard from which these individual scene depictions were taken for them to discuss. Their working relationship during Foreign Correspondent seemed very close.”*5

The crash, much more elaborate in design and execution than its 1930 predecessor, formed the basis for the climax of the picture. And unlike the dirigible crash in Lottery Bride, which took place in frozen environs of the Arctic Circle, the downing of the clipper in Foreign Correspondent takes place over the ocean. “The whole thing was done in a single shot without a cut!” marveled Hitchcock in his marathon 1962 interview with François Truffaut. “I had a transparency screen made of paper, and behind that screen, a water tank. The plane dived, and as soon as the water got close to it, I pressed the button and the water burst through, tearing the screen away. The volume was so great that you never saw the screen.”

The teaming of Alfred Hitchcock and William Cameron Menzies proved an inspired melding of two vastly different artistic sensibilities, Hitchcock being interested in the conveyance of visual information, Menzies in the deepening of the film’s graphic impact. Together, they produced one of the grand thrillers of the sound era. When production closed on May 29, 1940, after sixty-five days of shooting and eleven days of retakes, the negative cost of Foreign Correspondent stood at $1,484,167—by far the most expensive picture Hitchcock had ever made.

While Foreign Correspondent was in production, Our Town was being readied for release. To score the movie, Lesser selected Aaron Copland, whose only prior experience in feature films was with John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men. “This was not an ordinary motion picture,” Copland wrote. “The camera itself seemed to become animate, and the characters spoke directly to it. Once the narrator actually placed his hand before the camera lens to stop a sequence and introduce the next.… Percussion instruments and all but a few brass were omitted. I relied on strings, woodwinds, and the combination of flutes and clarinets for lyric effects. Since Our Town was devoid of violence, dissonance and jazz rhythms were avoided. In the open countryside scenes, I tried for clean and clear sounds and in general used straightforward harmonies and rhythms that would project the serenity and sense of security of the play.”

There was considerable discussion as to whether Emily should be allowed to live, her character having perished in the play. Menzies managed the design of the film so adroitly that the ending could go either way without sacrificing the underlying theme of the material. The decision, therefore, became a matter of retaining a few shots and discarding George Gibbs’ poignant moment at the grave of his young wife. Douglas Churchill, who would be reviewing the picture for Redbook, advised Lesser to use the happy ending, and Thornton Wilder, in the end, agreed. “In a movie,” Wilder reasoned, “you see the people so close to that a different relation is established. In the theatre they are halfway abstractions in an allegory; in the movie they are very concrete. So, insofar as the play is a generalized allegory, she dies—we die—they die; insofar as it’s a concrete happening it’s not important that she die; it’s even disproportionately cruel that she die.” To Martha Scott, who found the decision “deeply disturbing,” the playwright was even more direct: “Martha, it didn’t matter because my message in that play is to see life through the eyes of death.”

In a bylined article for The New York Times, Menzies described the challenge of Our Town as a problem of intimacy: “A story of ordinary people in throes of living and dying, the audience had to move along with the characters. To solve this, we filled the picture with small, intimate sets, practically put the characters in the audience’s lap with photography, and violated perspective throughout to heighten the moments of intimate drama.”

A press preview took place on the evening of May 9 at Grauman’s Chinese Theatre. Sol Lesser cabled Wilder after what he termed “a most unusual and successful” screening:

THE VERDICT WAS ONE HUNDRED PER CENT UNANIMOUS VERY FAVORABLE FROM BOTH PRESS AND LAY AUDIENCE.… I FEEL IT IS SAFE TO SAY THAT PICTURE WILL NOT DISAPPOINT ANYONE.

In a critical sense, Lesser was right. The film’s release on May 24 brought a wave of favorable notices, many outright raves. Bosley Crowther praised the filmmakers for utilizing “the fullest prerogatives of the camera” in making it a “recognized witness to a simple dramatic account of people’s lives, not just to spy on someone’s fictitious emotions.” Time hailed the picture’s simplicity and its fidelity to the spirit of the play. “Thornton Wilder wrote it in the only poetic idiom which Americans always understand—simple U.S. speech in which emotion supercharges the common forms. He wrote it out of the poetic materials to which Americans always respond—the casual routine of their lives amid the sights, sounds, smells of the American earth. Because Sam Wood, who directed Goodbye, Mr. Chips, and a splendid cast have transferred Our Town, the play, to film without disturbing this basic poetry, Our Town, the picture, is a cinema event.”

*1 Berger had delved into fantasy with a well-regarded version of Cinderella and was experienced in color filmmaking. He also worked in Hollywood, under contract to Paramount, at the same time that Korda was directing for First National.

*1 The exterior sets representing Basra had been built on Denham’s “City Square” lot, so named because the land had been inaugurated with the Everytown set for Things to Come.

*3 Sol Lesser always identified Menzies as the art director on the picture, but that title officially belonged to Lewis J. Rachmil, whose credits were primarily Hopalong Cassidy westerns.

*4 The principal screenwriter on Foreign Correspondent was Charles Bennett, who worked on six of Hitchcock’s British films, including The 39 Steps.

*5 When it came time for Hitchcock to make his traditional cameo appearance in Foreign Correspondent, he asked Menzies to direct the shot.