15

The Best Spot in Town

Bill Menzies thought his staging of Our Town “probably more important” to his career than Gone With the Wind. “Of course, GWTW helped me tremendously, as there was a strong ‘grapevine’ rumor about town that I had controlled the show,” he wrote. “But Our Town really did me more good as the picture was a very frail and delicate thing, and although the end got a bit ‘arty’ I think the first part is interesting inasmuch as its design is with faces and figures rather than moldings and architecture.”

On the strength of such an extraordinary pair of assignments, a flood of new opportunities came his way. In January, while he was shooting Our Town, writer-director Rowland Brown announced that Menzies would design Brown’s independent production Young Man of Manhattan, which was being set up at Paramount. In February, he was mentioned for the direction of Ben Hecht’s Angels Over Broadway. David Selznick contemplated a similar arrangement, proposing a deal for one picture a year but with yearly options for two. Then in March, Sol Lesser trumped Selznick by giving Menzies the plum assignment of directing a London-based production of The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling. Menzies wasn’t keen on returning to wartime England, but he was even less keen on working for Selznick again.

At the completion of Foreign Correspondent, Menzies spent a month working with director Frank Capra, who was mounting his first independent production, The Life of John Doe. “At first he bridled a bit and thought I was showing him how to direct, which of course is the danger of this system,” Menzies commented. “I ended up in a blaze of glory, though, because I took one sequence that was worrying him to death and took all the ‘eggs’ out of it.* I think they are as good drawings as I’ve ever done.”

While in the midst of working for Capra, Menzies signed on to another independent production. Producers David L. Loew and Albert Lewin had teamed to produce features for United Artists, Loew handling all the business affairs while Lewin, who had worked under the late Irving Thalberg at M-G-M, saw to the creative end of their productions. “David,” said Lewin, “felt strongly about the Nazi problem and wanted to make a contribution if he could, so he decided to make this book, although we were doubtful about its success in the United States.” The book, serialized in Collier’s, was Erich Maria Remarque’s Flotsam, a novel about “those unfortunate people compelled to escape Germany because of race or political opinion, who find themselves in foreign lands without passports, and who lack the legal right to live anywhere and are therefore shuttled back and forth over all the borders of Europe.”

The nomadic theme of Flotsam made the film more an exercise in mood and pattern than Our Town. Coming onto the project a month prior to shooting, Menzies, in Lewin’s estimation, made “upwards of one-thousand sketches” in consultation with director John Cromwell. “Photostats were made of these sketches and they were sent to the set to guide the director and cameraman in camera set-ups and compositions.” Assigned his own crew, Menzies worked ahead of Cromwell with a second camera and stand-ins, setting lights, arranging props, and achieving the angles called for in the photostats. “This second unit was responsible for savings in time in eliminating hit-and-miss production methods, and in creating a better-designed picture,” said Lewin. “The second crew also filmed many pickup and insert shots.”

Made at Universal, Flotsam drew on the talents of Jack Otterson, the head of the studio’s art department, who, like Menzies, was educated at Yale and the Art Students League. The most elaborate set for the picture—which soon became known as So Ends Our Night—was a carnival set depicting the Prater, known as the “Coney Island of Vienna” in pre-Nazi days. A brilliantly colored merry-go-round had animals of every description—giraffes, lions, tigers, elephants, zebras, ostriches. There was a flea circus and an animal show with prancing dogs, seals balancing balls, and a ballyhoo for the fleas. Across a narrow tree-shaded street was a sausage and beer stand. “I’m afraid it’s a little untimely, as it’s about the passport difficulties in Central Europe in 1937,” Menzies said of the story, “but for me it’s a field day.”

His charcoal sketches for the film, each of which took thirty to sixty minutes to compose, underscored the severity of the world in which the characters moved, their figures cold and isolated, their surroundings closing in on them. The picture, Menzies wrote at the time, had Fredric March and Margaret Sullavan “seeking throughout” to escape oppression in various Old World locales.

Therefore, melodramatic escapes keynote the picture. Here, again, violation of perspective becomes of importance. If it heightened the drama to shoot a tree from the viewpoint of an astigmatic worm sitting on a leaf of that tree, or even from that of the tree looking at itself, we did so insofar as the new 28 millimeter lens and our imaginations would permit. Jails, frontier offices, star chambers are exact replicas of such European interiors. There are 138 sets in So Ends Our Night, a new record, but they are not elaborate, and each one is vital. We tried to make each speak in visual terms the one word, “Oppression!” Therefore, the efforts of the actors to escape become more necessitous to the audience, heightening suspense and melodrama.

One Sunday while So Ends Our Night was in production, Menzies sat in his garden, his pad in his lap, and responded to a lengthy letter of war-related news from Laurence Irving. “I have had a very good year,” he wrote, dispensing with talk of the war,

and I have developed the job that I have always tried to put over so that it has put me in about the best spot in town. Please don’t think this smug. I am bringing it up principally to let you know that I really have developed the opportunity for application of our talents to the point where dozens of important people realize its importance, not only in added flavor and appearance but in the economic side, too. I have really proven that good composition is cheaper than bad and it is becoming a definite slogan around town. I am making between 500 to 800 drawings for each production, and working on twelve week guarantees I can do four pictures a year. It’s terribly applied, and every once in a while I am tempted to try and find an easier way of making a living, but it really is interesting and absolutely controls the whole staging of the picture. On the set the other day, I overheard the script girl say “we have six sketches to go” instead of saying “six more setups.” Of course, some pictures demand it more than others, but I try and get the “nuggets” so that I can display the technique of the thing strongest.

With the completion of his work on Our Town, Sam Wood went to Paramount to direct the unremarkable Rangers of Fortune and then to RKO, where his Kitty Foyle would bring Ginger Rogers an Oscar for Best Actress. Neither film, however, would be greeted with anywhere near the affection or respect accorded Our Town. When Wood agreed to make a comedy for producers Frank Ross and Norman Krasna, he insisted upon Menzies as part of the package. Krasna’s original screenplay, The Devil and Miss Jones, was designed to star Ross’ wife, the squeaky-voiced comedienne Jean Arthur. Appearing in the role of the billionaire real estate magnate John P. Merrick—the undercover owner of Neeley’s department store and the aforementioned Devil of the story’s title—would be Charles Coburn.

Krasna thought Sam Wood “a fabulous technician who knew nothing about the word” and therefore shot the script exactly as written. Menzies quickly grew to dislike the famously difficult Jean Arthur—he said that she had “legs like Indian clubs”—but rejoiced in the rare opportunity to design a comedy. “I think composition to punctuate ridiculous situations was used more and in better taste than is usual,” he said, reflecting on the project in 1947. “We also broke the rule that comedy should always be played in high key staging which, of course, has been adopted a great deal since. In other words, when melodrama and comedy were combined, we played it in lighting, staging, etc., as straight melodrama, although we didn’t lose the faces as much in lighting as we might in the more morbid type of melodrama.”

Lighting was almost an afterthought for the film’s sweltering afternoon at Coney Island, a sky cyclorama surrounding a ring of beach jammed with extras of all conceivable shapes and sizes, the detail on a scale worthy of Gone With the Wind. “The scene was as grotesque as a caricature by Reginald Marsh,” observed Philip K. Scheuer, a visitor to the set. “Men, women, children, papers, boxes, bottles, cups, blankets, campstools, underwear, medicine balls, scraps of food, and sand, sand, sand—in, under, and around them all, getting into everything. You wondered why flesh in gross tonnage lots was always so ugly.… The camera got down on its haunches, too, and ferreted out a group consisting of Jean Arthur, Robert Cummings, Spring Byington, and Charles Coburn at lunch. They, at least, appeared happy.”

The week production closed on The Devil and Miss Jones, nominations for the 13th Academy Awards were released to the press. Of the thirteen black-and-white features up for art direction, Menzies had worked on three—Rebecca, Foreign Correspondent, and Our Town. And the eventual winner in the new color category was also a Menzies-related project, The Thief of Bagdad. That he had greatly influenced the look and visual impact of two of those films is beyond question. It is doubtful, in fact, that Lew Rachmil could ever have mustered a nomination for Our Town without Menzies’ involvement in the conceptual layout of the film and its overall design. Yet there was no talk of a special award that year, and Menzies’ name went missing in all the coverage that surrounded the event on February 27, 1941.

Composition in service of the ridiculous: Thomas Higgins (Charles Coburn) and Miss Jones (Jean Arthur) look on as the officious Mr. Hooper (Edmund Gwenn), dubious of Higgins’ ability to sell slippers, carefully files away his new employee’s disappointing score on an intelligence test. “Don’t feel badly—he’ll get his just deserts one of these days,” she soothes. “I’d like to be as certain of the hereafter, Miss Jones,” replies Higgins, actually Merrick—the undercover owner of Neeley’s Department Store. (AUTHOR’S COLLECTION)

Menzies’ name on a picture invariably drew critical comment, even when such well-meaning recognition was misplaced. “Suspenseful and highly exciting plot has been placed in a William Cameron Menzies production that lends authenticity and dignity to the story,” Variety noted vaguely in its review of Foreign Correspondent. “The sets are equal in their size and scope to the extent of the international spy story being unfolded.” So many critics assumed Menzies’ credit on The Thief of Bagdad was for design and art direction that he felt compelled to take out a full-page ad in Daily Variety and The Hollywood Reporter to deflect such notions: “Vincent Korda—and Vincent Korda alone—deserves all the credit for the imaginative sets and the designing of The Thief of Bagdad, a truly great job.”

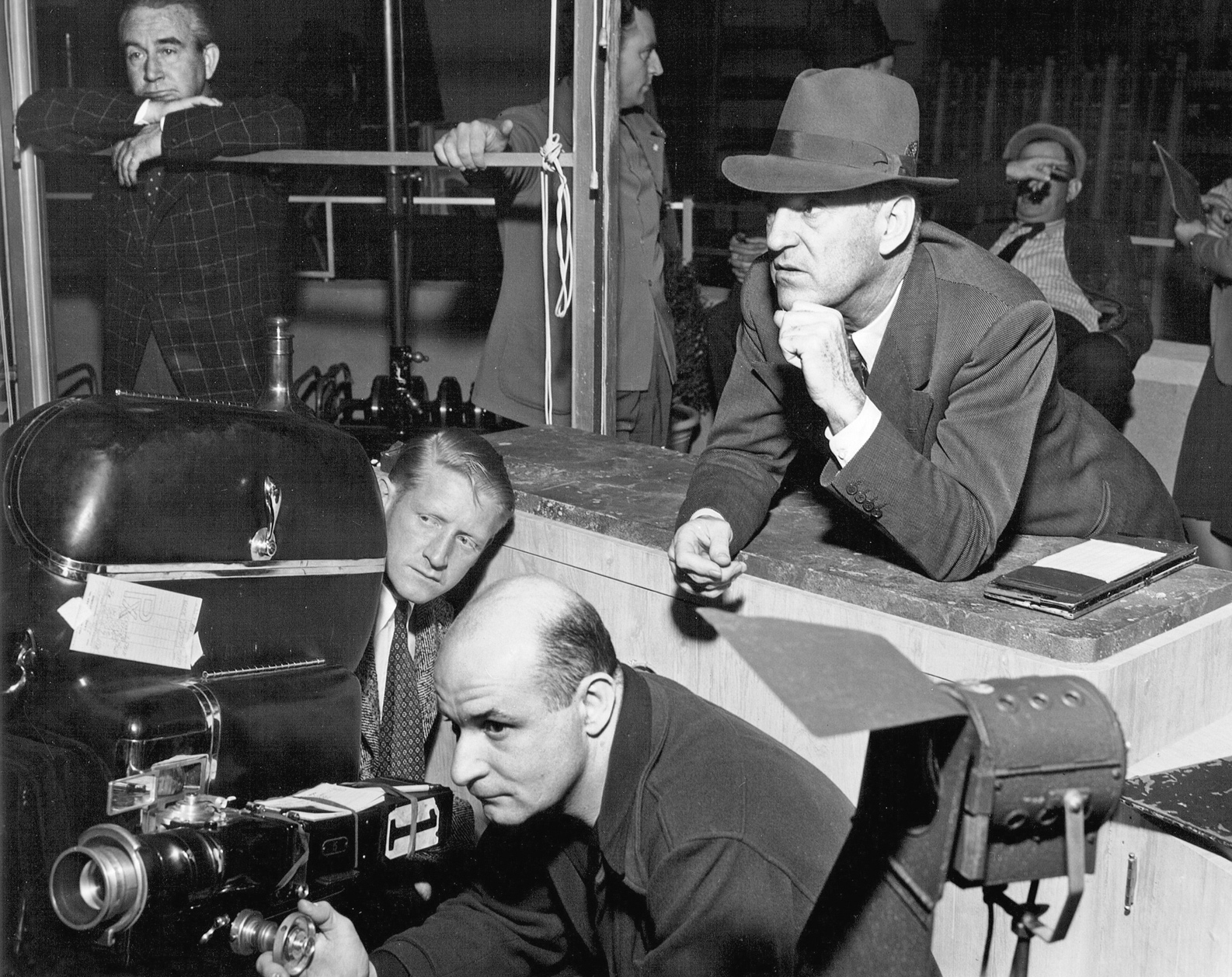

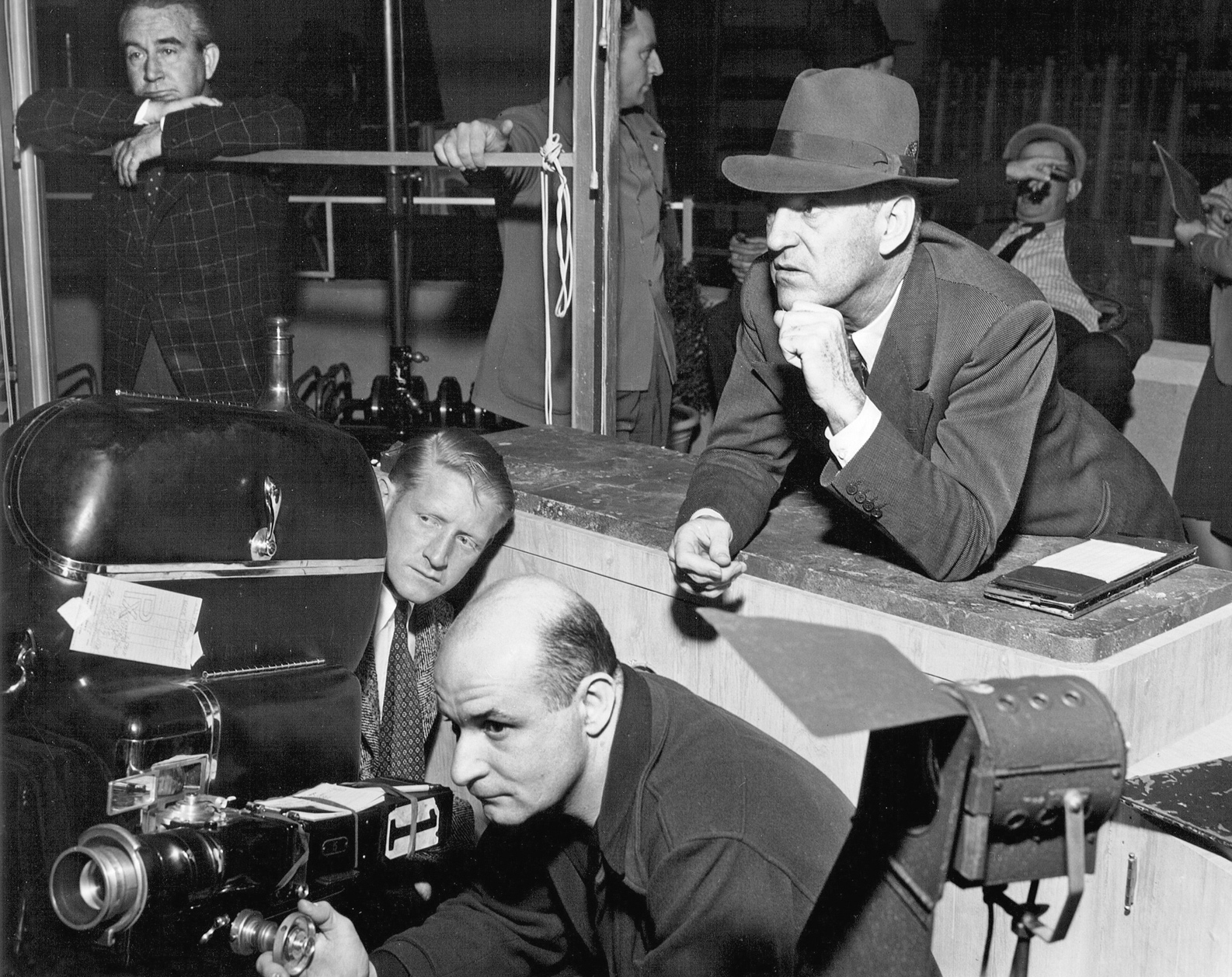

Menzies was always at hand when Sam Wood was directing. Here, on the set of The Devil and Miss Jones (1941), he watched as Charles Coburn rehearsed a scene in which he attempted to fit a belligerent young girl with a pair of high-topped shoes. “Suppose you wire that kid’s pigtail,” Menzies suggested. “When Coburn is trying to shoe her like you would a horse, and her pigtail stands out in fright, it ought to be a laugh.” Wood embraced the idea and held production until the effect could be rigged. (ACADEMY OF MOTION PICTURE ARTS AND SCIENCES)

“I am a Hollywood anomaly,” Menzies wrote in a bylined piece for The New York Times.

In a town where the spotlight is the goal of most, my work is the less noticeable the better it becomes. As a production designer, it is my job to dramatize the mood of a picture and to keep it “in character.” This is done simply by coordinating every phase of the production not covered by dialogue and action of the players. Camerawork, settings, decorations, costumes, must all be carefully planned in advance, so that each contributes in its own way to the desired effect of the whole. Prior to the application of this theory of motion picture production, which, I believe I originated in Hollywood (although it is an old principle of stage presentation), the making of a motion picture was the work of too many cooks, each a chef in his own right, with the result that each department worked for its own aggrandizement rather than for unity.… It is but the principle of architectural engineering, which I studied at Yale University in my youth. I have applied it to the making of motion pictures, for the better, I think. And I remain a Hollywood anomaly.

On February 4, 1941, Daniel T. O’Shea advised David Selznick that Menzies had entered into a deal with Sam Wood, although it wasn’t yet in writing. “Bill gave me certain promises,” O’Shea, now general manager of David O. Selznick Productions, contended, “which he just ignored when it came to making a deal. I think the secret of it is that he just has an easier time of it with Sam Wood. He says his wife doesn’t want him going through long hours with us and that, frankly, he’s not able to take it anymore.” Menzies had laid it on Mignon, but it’s unlikely she ever mentioned the subject, much less delivered an ultimatum. She never pried into Bill’s work at the studios, nor, for that matter, ever expressed much interest in it, choosing instead to keep his home life as he wanted it. “Everything was there exactly the way he left it,” said their daughter Suzie, “because that was the way things were. Tommie Carter, our cook, was in the kitchen, Mother was with her bridge club, Jean and I were at school, the dogs were there. He came back to exactly the same thing he left, which I think he appreciated.”

Jean Menzies graduated from the Westlake School for Girls in 1937. “She was very shy, very studious,” said her younger sister. “A great student. She got accepted into Stanford when she was sixteen. Then I think she just got cold feet.” Jean wanted to be an artist, but she wasn’t as naturally talented as her parents. She attended Otis Art Institute for a while, then, at her father’s insistence, went back to school in 1940 to take “a good stiff course in life drawing” which she seemed to enjoy. Suzie, at age fifteen, was still at Westlake and usually present for nightly dinners, sometimes to find that her father had been drinking.

“There was always that tension,” she remembered. “Was he going to come home drunk? How was Daddy going to be when he came through that front door? We didn’t know what we were going to have. His eyes would get very big and very blue and he’d sit there and glower at us like this big toad. Then the next day he’d be wonderful and all apologies to Mother—typical drunk behavior.” Mignon would sigh and try not to set him off. “It was an odd marriage. It’d be hard to imagine two people more unalike. Mother had this prissy side to her, which Daddy certainly did not. She didn’t drink, she didn’t smoke, she went to church. And she had no spirit of adventure whatsoever. But she was like a rock to him. She was something that he could always come home to. She took care of everything. She paid all the bills. She took care of us. Everything she took care of to make his life more comfortable. She carried his breakfast up. We were all trained that when somebody called on the phone to say he was not at home. We were very well trained to take care of Daddy—especially Mother. Grandmother was trained to keep out of his way. And he adored Tommie, who was the best cook in Beverly Hills.”

Nanon Toby, who tried to scuttle the “horrid match” between her daughter and Bill Menzies, had come to live with them on North Linden Drive, where she would generally stay in her bedroom and sip cheap wine. “She was a typical Southern lady; she was Blanche DuBois,” Suzie said. “Only she wasn’t crazy, she was just a drunk. But she always looked nice. She was very sort of chic. Even in these old clothes that she had for years she always managed to put a little scarf on or earrings. She was of another era, yet she was the first woman I ever knew who wore pants. To the beach. She’d wear these sort of pajama-like things. And these big hats, and these flowing scarves. She’d look like Isadora Duncan. She was very intelligent, but we never got along.”

Nan was always in the background, a constant, lingering presence in a household that seemed all too often to be dominated by women. She and her son-in-law rarely spoke, and he took to referring to her as “Creeping Jesus.”

The “deal” with Sam Wood meant that Menzies would be associated with Wood on a succession of important pictures, Sam typically commanding a fee of $75,000 and Menzies drawing his established rate of $1,000 a week from Wood’s employer of the moment. Together, they constituted one outstanding director, capable of working to the industry’s highest artistic standards. Their partnership officially began in January 1941 when Wood was engaged to direct Kings Row for Warner Bros. As part of the deal, Jack Warner agreed that Menzies would join Wood as production designer, but that they would use him “only five weeks top.” Wood’s commitment, on the other hand, would be for fifteen weeks.

A long, overwritten novel by the onetime dean of the Curtis Institute of Music, Kings Row displayed the rancid underside of Our Town, a story bereft of Thornton Wilder’s poetic sensibilities but long on fascination, the book being, as The New York Times put it, “a choice combination of murderous melodrama and psychopathic horrors.” Warners jumped on the screen rights when the book was published by Simon and Schuster in April 1940, paying $35,000 to trump a bid from 20th Century-Fox. Clearly someone at the studio thought it suitable for motion pictures, but just exactly how to get it past the Breen Office was a matter of considerable discussion. Wolfgang Reinhardt, an associate producer on the lot, resisted the assignment: “As far as plot is concerned, the material in Kings Row is for the most part either censurable or too gruesome and depressing to be used. The hero finding out that his girl has been carrying on incestuous relations with her father, a sadistic doctor who amputates legs and disfigures people willfully, a host of moronic or otherwise mentally diseased characters, the background of a lunatic asylum, people dying from cancer, suicides—these are the principal elements of the story.”

Another Warner producer, David Lewis, had an entirely different take on the book. “It was long and contained enough material for five movies,” he said, “but the main story was a very powerful one of two boys who grow up in a small town as inseparable comrades. Parris Mitchell, brought up by his gentle European grandmother, wants to be a doctor, while Drake McHugh is a fun-loving young man with little thought for the future.” On July 11, 1940, a week after Reinhardt’s demurral, Lewis received a “pink note” from executive producer Hal Wallis: “In view of your interest and enthusiasm for the book Kings Row, I am assigning this subject to you.”

In developing the script, Lewis turned to a frequent collaborator, screenwriter Casey Robinson. “He happened to be leaving on a vacation to the Far East,” Lewis recalled, “so I gave him the book and he promised to read it on the trip. When he returned, I asked him about it. He told me he had gotten as far as the incest between Dr. Tower and his daughter and, certain the book was completely unfilmable, had thrown it into the Indian Ocean.” It was the first 200 pages of Kings Row that interested Lewis: “The Breen Office had already frowned on our purchase of the book, but by then I already had the reason for Dr. Tower’s killing of his daughter Cassandra and himself. Instead of incest, which, of course, was not allowable, I reasoned it would be equally believable that he would keep from Parris, his promising pupil, the one thing that had ruined his own life—an insane wife.”

Sam Wood wanted Ginger Rogers for the part of Randy Monaghan, a beautiful Irish girl from the wrong side of the tracks, but Lewis held firm for Warner contract player Ann Sheridan, convinced—correctly, as it turned out—the role would make her a star. Early on, Ronald Reagan was set for the role of Drake, which would turn out to be his best and most memorable part. The casting of Parris proved problematic: Lewis wanted Tyrone Power, but Fox’s Darryl Zanuck demanded too much for him, including two Errol Flynn commitments. With time running short, Wood settled on Robert Cummings, who had played the earnest Joe O’Brien in The Devil and Miss Jones. Cummings, under contract to Universal, could be had for $1,000 a week, but was in the middle of filming a Deanna Durbin picture, forcing a delay in the start of Kings Row.

When Menzies checked onto the Warner lot, he had as his starting point a temporary screenplay dated February 7, 1941. Work was progressing, but there was enough to start visualizing the early portions of the film, including the material establishing insanity in the Tower family. The script began with the title: KINGS ROW 1890 “A good town, everyone says. A good clean town. A good town to live in and a good place to raise your children.” Cut to a horse and buggy approaching the camera. “While we discussed the script and the content (and agreed on it so we weren’t two people thinking of a picture but one person thinking of a picture), Bill Menzies sketched every scene, every camera angle, every set-up,” said Casey Robinson. “He numbered them so that, when Sam finally went onto the set, all he would have to say to James Wong Howe was, ‘Jimmie, this is scene number ten,’ and Jimmie would go to work lighting the set while Sam worked with the people.”

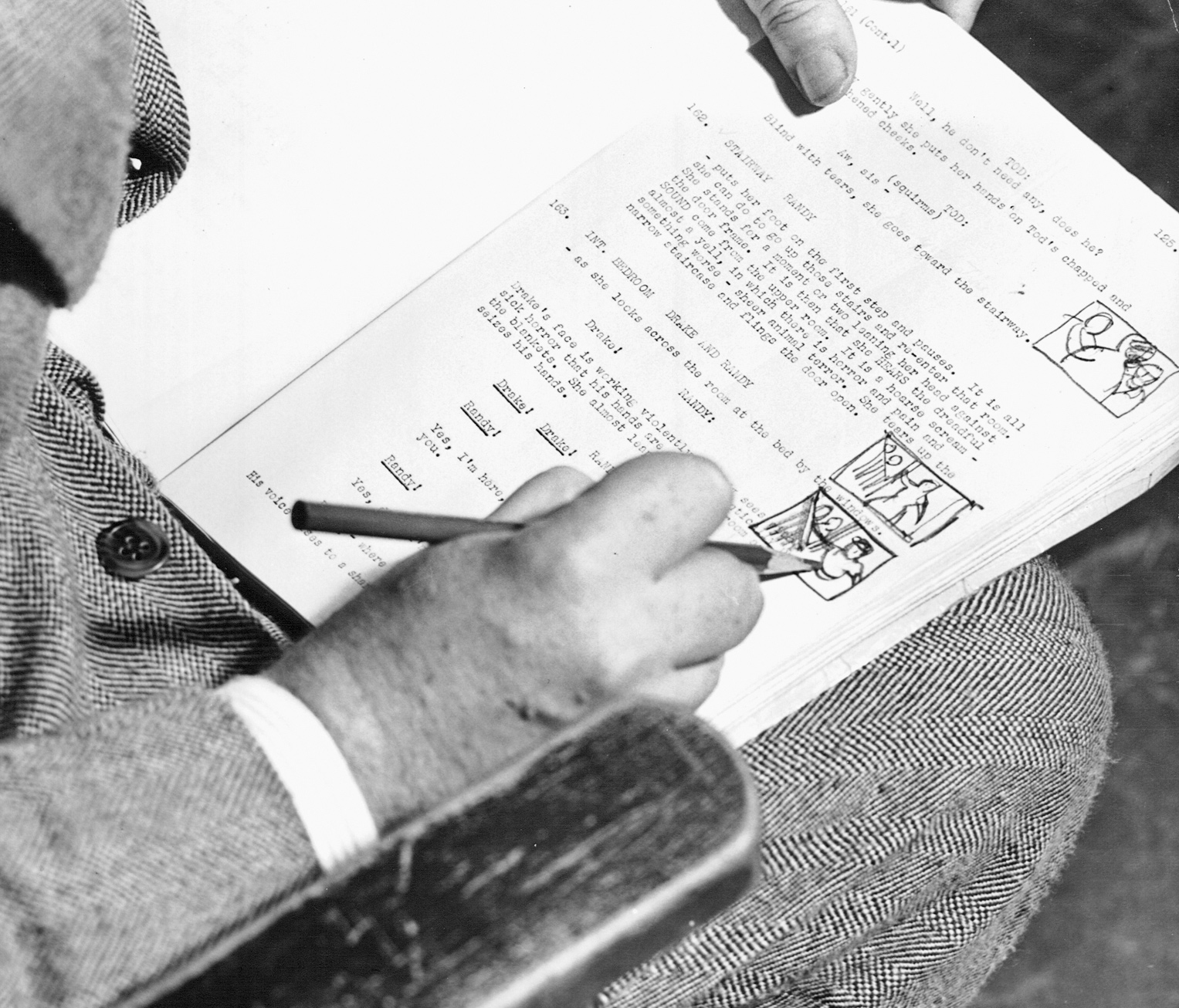

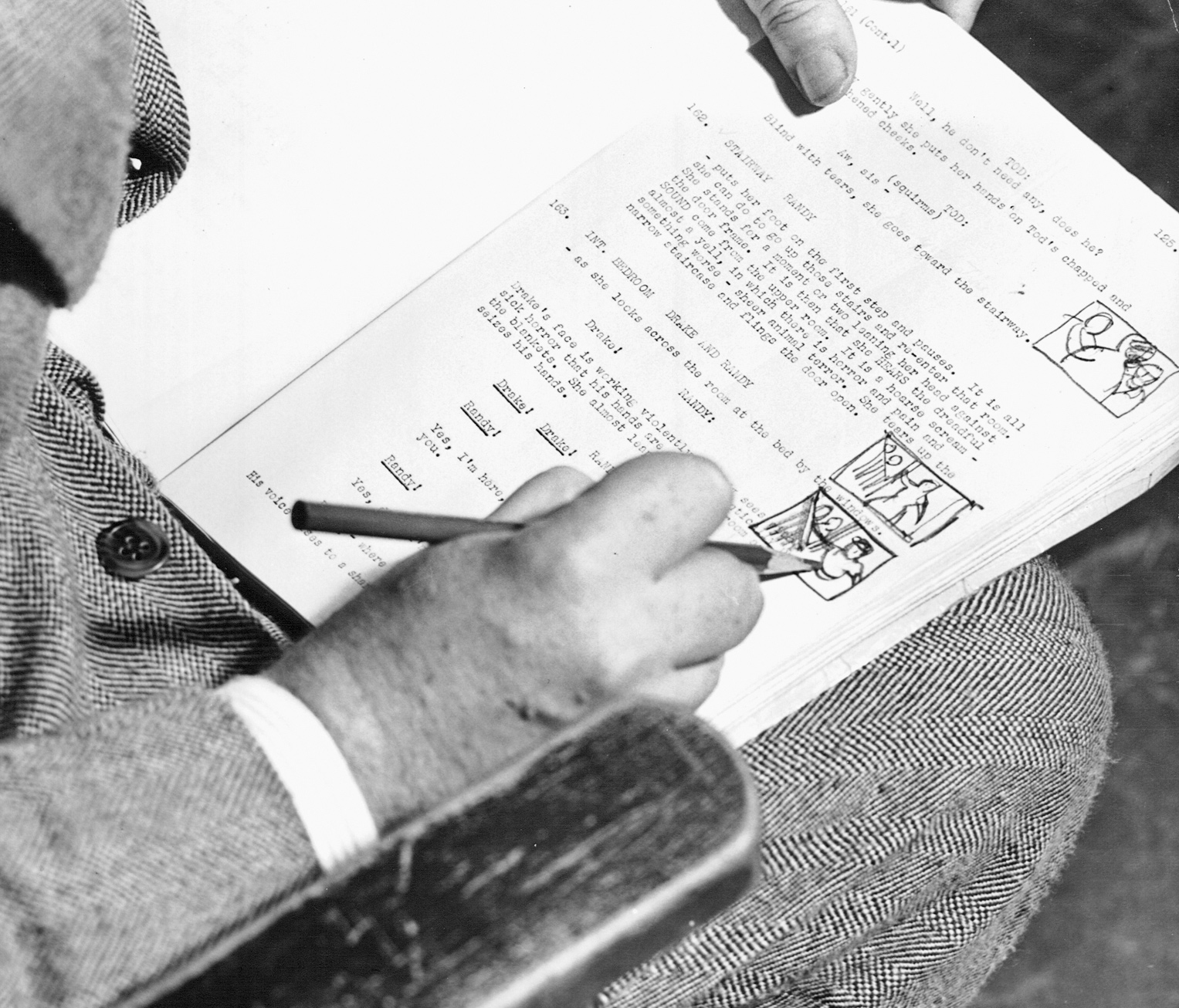

The shooting final, dated April 13, brought a sharp letter of protest from Joseph I. Breen, who questioned the wisdom of making any picture—even one rewritten to conform to the provisions of the Production Code—from a novel so vividly identified in the public mind as “a definitely repellent story, the telling of which is certain to give pause to seriously thinking persons everywhere.” It fell to Menzies to stage the picture in a way that would be faithful to the moods and rhythms of the original story while complying in all respects with the demands of the Code. He began by visualizing the individual characters and the costumes they might wear. “I draw the figure in connection with the ground—he grows out of the ground as much as a tree does,” he said. His initial sketches, which took the form of thumbnails in the margins of the script, were studied by Howe with an eye toward managing the visual transitions between scenes, achieving a “continuity of movement” with complementary compositions at the end of one scene and the beginning of the next. “It is,” said Menzies, “the liquid quality of movement which is the unique asset of motion pictures.”

From the revised thumbnails, art director Carl Weyl was able to design some seventy sets for the picture, rendering many as scale models. Working from those models, Menzies made his detailed continuity sketches on illustration board with Paillard and Siberian Pit charcoal, indicating highlights and tonal values with black and casein, an opaque white. When it came time to build the sets, only those portions to be seen by the camera were actually fabricated. As Howe said of Menzies, “He’d tell you how high the camera should be. He’d even specify the kind of lens he wanted for a particular shot; the set was designed for one specific shot only, and if you varied your angle by an inch you’d shoot over the top. Everything, even the apple orchard, was done in the studio. The orchard was such a low set that it was very, very hard not to show the banks of lights. I had to hang shreds of imitation sky over it, blending one with another to hide all that equipment. Menzies created the whole look of the film; I simply followed his orders.”

Bob Cummings’ absence afforded the director an unanticipated opportunity. “Sam Wood was absolutely wonderful,” Ann Sheridan said. “And for the first time in any picture we rehearsed three weeks before one single shot was made. The sets were up and we knew where we were going, what was going to happen.” When filming finally did begin on July 14, the scenes between Sheridan and Reagan were the first to be made, Cummings joining in only when he wasn’t needed at Universal.

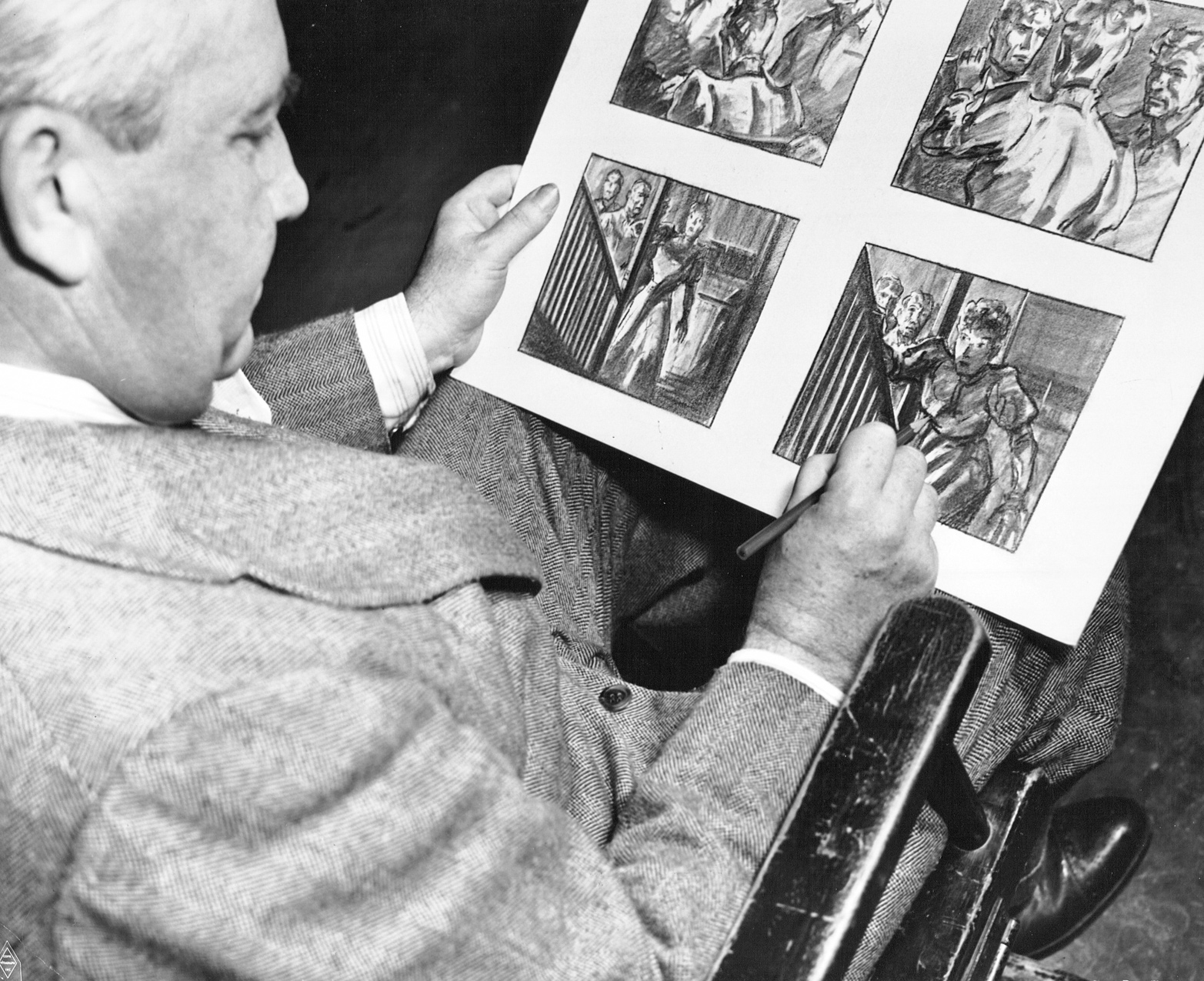

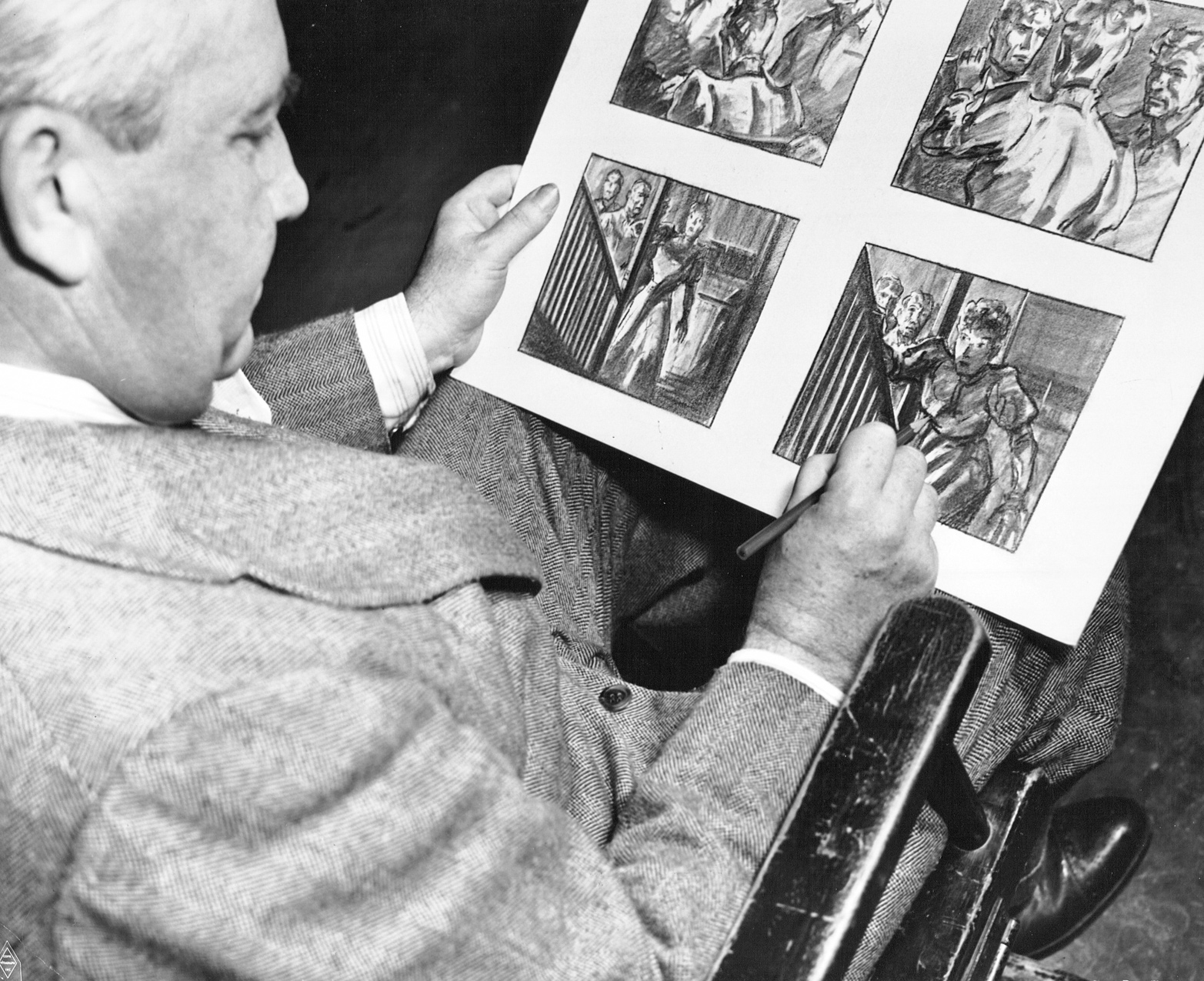

On the set of Kings Row (1942), Menzies shows how he captures his first impressions of a script by making “shorthand sketches” in the margins. (AUTHOR’S COLLECTION)

Wood quickly came into conflict with the Warner way of doing things. Two days into production, he declared that he wanted two takes printed for every shot he made. When it was explained they permitted only one print of a given scene, Wood said that he wanted two takes so he could use parts of each, thus enabling him to cut down on the total number of takes he made. Noting that Wood and Menzies made very few setups but that they were “very thorough and complete,” unit manager Frank Mattison thought it advisable to let Wood have his way. “Working with Menzies makes you really think,” Wood told a visiting journalist. “You play the scene over mentally and get the action—then, if the scene happens to be in a living room, you don’t get the doors or the furniture in the wrong place and spoil the scene because you’ve spoiled the action. We’ve gone over everything, there’s no other way to see it. Makes for faster shooting—and saves film.” Added Menzies: “We’re two halves of the same thing. Sam likes me to stay on the set. We work everything out together.”

Taking his thumbnail sketches up large, Menzies demonstrates how he refines them into a continuity board. When the Breen Office cautioned the studio over this scene in which Drake (Ronald Reagan) discovers his legs have been amputated, Menzies threw the visual emphasis to Randy (Ann Sheridan) by reflecting in her anguished reaction shots the depth of Drake’s horror. (AUTHOR’S COLLECTION)

David Lewis, another veteran of the celebrated Thalberg unit, had never before observed a director quite like Wood: “He knew nothing about the camera, nothing about script, and little about casting. Not only was Menzies on the set for everything, Sam rarely let me out of his sight either. Before shooting he would say to me, ‘What is this scene about?’ I would tell him and he would whisper in an actor’s ear the magic words that brought forth a fine performance. In spite of his unorthodox method of working, I thought him worth his money.”

Wood proved his worth beyond all doubt on the matter of Drake’s accident and the subsequent amputation of his legs by Dr. Gordon. The doctor’s sadism could only be implied, the nature of Drake’s injuries suggested but not shown. Forced to work the rail yards, Drake is thrown into the path of an oncoming train when a stack of pallets collapses. Menzies worked out the continuity of shots so that an exterior dialogue between Drake and Randy ended on the image of an untended coffeepot. Dissolve to a shot of Drake clinging to the outside of a slow-moving train, dropping off as the engine picks up speed. The engineer turns to wave, then reacts in horror as he sees the hazard of the unstable cargo. He shouts a warning just as the pallets begin to tumble and Drake vanishes from the bottom of the frame. End on a shot of the coffeepot crushed under the wheel of a boxcar.

When he awakens, Drake is under the care of Randy and her family. Wood at first resisted the idea of a hole in the bed for Reagan’s legs, so that when he turned to the wall, his whole body wouldn’t turn with him. Said Lewis, who was called to the set, “The answer was fairly obvious.… That would make turning to the wall both difficult and heartbreaking. He tried it and it worked. Menzies, meanwhile, was standing there. As I turned from Sam he whispered, ‘I’ve been trying to get him to do that all day.’ I believed him; Menzies was not one to miss a trick.”

As Reagan eased into the bed, he could sense its impact on-screen and chose to remain in place as Howe and his crew arranged the lights. “I had experienced a shock at seeing myself with only about two feet of body,” he wrote in his autobiography, “and I just stayed there looking at where my body ended. The horror didn’t ease up. When the camera crew announced they were ready, I whispered to Sam Wood … ‘No rehearsal—just shoot it.’ I guess he understood. When he said, ‘Action,’ I screamed, ‘Randy, where’s the rest of me?’ while I reached with my hands, feeling the covers where my legs should have been. There was no retake. Sam quietly said, ‘Print it.’ I realized I had passed one of the biggest milestones of my career.”

The beginning of Kings Row was inspired by the opening of Our Town, where Frank Craven approached the camera as the titles appeared. Casey Robinson had a similar idea, the camera panning through town, but it lacked the focus of a single figure the eye could follow, and Menzies solved the problem with a hay wagon that appeared in the far distance and grew closer as the credits progressed. The effect was lyrical, the pan continuing past the sign KINGS ROW 1890 and on to the schoolyard, where the main characters are introduced as children and the close relationship between Parris and Cassie is established in the apple orchard that gave Jimmie Howe such fits. “It is possible,” Menzies observed, “to set the mood, deliver your credits, and open up on the first scene of the picture with the same footage.”

For Kings Row, Menzies wanted sharp tonal contrasts that worked against the genteel pretensions of the town. The period costumes were either very black or very white, while the walls of the sets were often white. As with Our Town, he chose to work in close, his angles low and clean, building his compositions with the faces rather than the sets. “When Parris arrived home,” said Casey Robinson, “you just saw a little scene between two cars and you saw a boy’s face, worried. That’s what the story was about. It wasn’t about a train coming into a station.” As with Our Town, Menzies established a recurring pattern of horizon fencing, adding a stile where the characters could cross over and transitions could symbolically take place. When it comes time for Parris’ passage from adolescence into adulthood, it is accomplished with young Scotty Beckett, in short pants, stepping over the fence, the camera holding on his feet as he disappears from view. A dissolve indicates a change of season and the passage of years, and then two adult feet step back over the fence, the camera holding on them until tilting up to reveal a grown Parris in the person of Robert Cummings.

Said Menzies,

There’s a series of dramatic narrative sketches which, while they presented the possibility of a direct attack, called for all the ingenuity we could muster. Six sequences in a doctor’s dusty study—and you have to sustain interest and dramatic action. Drab, rundown-at-the-heels place. We used the doctor’s books for composition. Jimmie [Howe] caught the atmosphere beautifully; Jimmie’s one of the best cameramen I ever worked with, has a great sense of how to light a set. In this truly American, musty 1900 doctor’s office we used every device to emphasize the atmosphere and sustain drama. Fuller’s earth on books to give dusty effects, diffused effects through old lace curtains, dust in the crevices and sheen on the highlights of the tufted leather chair; and the lighted edge of an old tome—in one sequence we caught this highlight, held it a split second, then moved the man across it. Just chinning yourself on nothing—six sequences in that one study.

One of the more controversial aspects of the novel was a scene in which Parris administered a fatal dose of morphine to his beloved grandmother, stricken with cancer. The Code expressly forbade mercy killing when “made to seem right or permissible” and the filmmakers, at an April 23 meeting with Breen and deputy Geoffrey Shurlock, had agreed to remove any suggestion of it. There was, however, a feeling the episode carried weight only when expressed in terms of the difficult moral choices faced by a young doctor, and the decision was made to shoot the scene regardless, with the hope the staging would be subtle and artistic enough to gain the reluctant approval of the PCA. James Wong Howe described the design of the scene and how it was photographed:

Although the Production Code forbade “the suggestion of a mercy killing of the grandmother by Parris,” Menzies was able to stage the scene at her deathbed so that a hypodermic needle loomed large, a pitcher and basin completing the composition and firmly drawing the eye to the foreground. Parris’ discovery of his grandmother’s grave condition is played with the needle in hand, suggesting the option of euthanasia.

We had a shot with a hypodermic needle in the foreground, about 18 inches from the lens. From behind we saw a bed with the grandmother of this boy, and we saw … Bob Cummings about twenty-five or thirty feet in the background. The camera is stationary until he comes into the foreground and picks up this needle. As he walks out of the camera and starts to cry, we know what has happened.… This was all done in one shot with the camera in one place. It was a difficult shot for me. I had to carry the focus, to make this hypodermic needle very sharp and also the background sharp. That was accomplished by using a wide angle lens; I think I used a 25mm or half-inch lens to carry the focus. I had to stop down, oh, around f.8 to keep it sharp. By stopping down to f.8, I had to use much more light than I would photographing normally at f.2.3 or 2.8. But it worked out.

On August 20, snowy scenes of Kings Row at wintertime were being shot on Stage 1. Ann Sheridan was making The Man Who Came to Dinner, alternating between it and Kings Row, often on split days that scarcely left her time for lunch. Bob Cummings was still over at Universal, romancing Deanna Durbin, and the company was eleven and a half days behind on a forty-eight-day schedule. “We must get one thing settled in the next few days and stop all this nonsense,” Jack Warner thundered in a memo to David Lewis, “as we have never done business this way and I am not going to permit it to start.”

Warner was upset that the part of Cassandra Tower was yet to be filled. Bette Davis wanted the role, but it was considered too small for a star of her magnitude. Olivia de Havilland had turned it down, as would Ida Lupino. Warner suggested either Joan Leslie, Susan Peters, or Priscilla Lane as “the best we can get” but Sam Wood would have none of them. In September, with the film nearly ten weeks into production, Wood went to Paramount to shoot five days of tests for his next collaboration with Menzies, For Whom the Bell Tolls. One of the actresses he saw was Betty Field, who was trained at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts and known primarily for her work on the stage. Wood thought her ideal casting for a troubled girl driven to the edge of madness by heredity and parental abuse, and he arranged to have her borrowed by Warners on a three-week guarantee.

“He was wonderful in giving confidence to actors and trusting them and recognizing when they played a scene well,” Field said of Wood.

For the part I played in that [picture] they tried out hundreds of girls. They couldn’t find any. They finally auditioned me—they were so particular to get this part just right, because it was such an odd part. She was insane, and yet you couldn’t say she was insane. Due to censorship you couldn’t say there was incest there, you had to imply it by looks between the father and daughter. Only if you’d read the book would you know why they were staring at each other. But I auditioned—actually they gave me a screen test, and he worked so hard on the screen test that actually it took a whole day to do a screen test of a scene. Then they put it into the picture. They didn’t bother doing that scene again. He perfected it and perfected it and decided it was just what they wanted for Cassie.

To give Cassandra a ghostlike quality, Menzies specified a No. 1 makeup, which was almost pure white and seldom used. Her frantic encounter with Parris in the empty Tower house, a thunderous storm raging outside, was one of the last scenes shot, the implied justification for the doctor’s murder of his own daughter. Menzies staged the scene against a backdrop of lightning, the screen going from intense blackness to flashes of brilliant illumination, the characters growing closer and more passionate with each desperate glimpse. His handling of the material was well within the dictates of the Code, yet with the implication clear and the imagery unmistakable—no rawer sex scene was to be found in any mainstream American film of the decade, a dazzling example of how mood and subtext could trump the work of gifted actors and render a scene’s dialogue inconsequential.

When Kings Row finished on October 7, 1941, it was twenty-three days over schedule and nearly $300,000 over budget. Most of the delays and overages could be attributed to switching the schedule around, which resulted in carrying some actors for longer terms than anticipated, as well as many sets, which had to be lighted and relighted. “Considering the broken manner in which this show has been shot as regarding sets, cast etc., I only hope it fits together right,” said Frank Mattison in a memo to his boss, production manager T. C. “Tenny” Wright. “I have never seen a picture shot in such a hurried manner as this picture has been made. Most of the circumstances were beyond our control and the insistence of Mr. Wood that we have Robert Cummings play the lead in this picture.”

For producer David Lewis, one of the most memorable aspects of Kings Row was the opportunity to work with William Cameron Menzies, whom he described as “probably the most brilliant man I have ever known in his field.” For Lewis, the picture constituted a catalog of fine visual touches, some of which he noted in the pages of his autobiography: “Among Menzies’ contributions, apart from the entire tone of the film, were the magnificent opening shot in the schoolyard … Parris stepping over the stile into adulthood … the staging of the accident in the railroad yard … the sight of the crushed coffee pot to indicate Drake’s legs … the lighting in the bedroom at the grandmother’s death … the long telegraphic montage between Kings Row and Vienna … and many others.”

It was, Lewis would say, economical filmmaking with a grandeur unusual in even the priciest of Hollywood epics, abetted as it was by Erich Wolfgang Korngold’s majestic score, far from the astringency of Aaron Copland yet no less effective. Years later, in 1951, Menzies himself weighed in on the subject, telling his colleague Leo Kuter that he considered his “very best effort as a production designer” to have been the Warner Bros. production of Kings Row.

* According to Menzies’ daughter Suzanne, this was the convention sequence, populated with scores of black umbrellas, shot at Hollywood’s Gilmore Field. The film was released as Meet John Doe (1941).