16

Address Unknown

On May 17, 1941, Sam Wood wrote to Bill Menzies from New York: “I got a phone call at Baltimore which I am not at liberty to disclose, but we have one of the big plums. If you guess what it is, it is very important to treat it confidential at the present time.”

The “big plum” was Ernest Hemingway’s For Whom the Bell Tolls, an assignment Wood effectively inherited from his old boss Cecil B. DeMille. (DeMille thought the novel, when he finally got around to reading it, “really in a communist cause.”) Unlike Kings Row and Our Town before it, both of which were entirely studio affairs, much of the Hemingway picture would be shot in the Sierras. “On location,” groused Menzies, “all you have is a series of dialogues with one party shouting to another party on the opposite hillside. On indoor sets we have absolute control. We can avoid crosses in action, and actors are never on the same level when we build sets. I’ll have a lovely time when we get going on For Whom the Bell Tolls.”

Hemingway reportedly modeled the character of Robert Jordan on his pal Gary Cooper, and he had urged DeMille and Paramount to cast Cooper in the film version, a matter that would require the acquiescence of Sam Goldwyn. Meanwhile, columnist Jimmie Fidler declared the latest candidate for the female lead to be Ingrid Bergman, “who’ll get it if boss David O. Selznick says yes.”

The item was probably a plant, as Selznick was vitally interested in getting Bergman—who had just one American release to her credit—the role of Maria, the young refugee whose parents were murdered by the nationalists during the early days of the Spanish Civil War. Under pressure from Selznick, Hemingway got on board, acknowledging that he, too, would like to see Bergman play the part. But resistance at Paramount was fierce, and the part remained uncast when Wood committed to making the film. There was also the matter of an adaptation, which production head B. G. “Buddy” DeSylva put in the hands of novelist Louis Bromfield. Preparations went forth as Wood and Menzies immersed themselves in the shooting of Kings Row.

There was little time between the close of Kings Row and the start of For Whom the Bell Tolls, the preproduction phase beginning with a convoy of studio cars, trucks, and buses making its way up Route 99 to the California gold rush town of Sonora, 350 miles north of Los Angeles. From there it was some fifty miles east to the Dardanelle, a rustic resort just below the Sonora Pass, where the company would be quartered while Wood, cinematographer Ray Rennahan, and Menzies scouted locations and waited for snow. (As his one hedge against the random compositions of nature, Menzies had some gigantic fake boulders fabricated in Los Angeles and hauled north on a flatbed truck.) Often, Wood would settle on locations that differed for every shot within a given sequence, giving Rennahan’s Technicolor cameras the full benefit of their spectacular surroundings while leaving it to Menzies to lend visual continuity to the footage.

“He would select one location for the shot of the bridge when [the old Spanish guide] Anselmo pointed to it, when he and Jordan paused on the trail,” recalled Herbert Coleman, Wood’s script supervisor on the picture. “The location for the scene between Anselmo and Jordan was picked on the side of a mountain miles away. For the close shot of Jordan in the same scene, another location on another mountain was his choice. For Anselmo’s close shot, still another mountainside. To make it seem as if all the scenes were shot in the same location, the same gnarled, twisted limb of a storm-weathered pine tree was placed in each scene.”

When the snows came, Wood sent for the rest of the shooting unit, which included technicians, grips, horses, cavalrymen, and a group of players headed by Joseph Calleia, the Maltese actor who would be playing El Sordo, Hemingway’s Gypsy renegade. Filming commenced on November 13, 1941, and soon the company was completely snowbound.

“LOCATION CONDITIONS HERE QUITE PRIMITIVE AND VERY COLD,” Menzies wired Mignon, “BUT FEEL WELL. STUFF SHOULD BE BEAUTIFUL.” A few days later, in a handwritten note, he added: “We are going very slow as we have a three-hour shooting day. I finally had a bath. We have to sleep with fires going or the little plumbing we have freezes. It’s been 2 above and 2 below zero.”

“We were supposed to meet him for Thanksgiving dinner in Yosemite,” recalled Suzie Menzies, “but he could never get there.” Then came December 7 and news of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Immediately, all planes in California were grounded, including the three bombers that were supposed to take part in a mountaintop assault on the rebels. “Boom!” said Ray Rennahan. “They pulled us back, pulled the whole company back until they could get permission to use the planes.” Production on For Whom the Bell Tolls was suspended until the following summer, when the aircraft could presumably fly once more and the casting of the leads would be settled.

When Henry Louis Gehrig died on June 2, 1941, a scramble for the rights to his life story was set in motion. The Yankee first baseman’s dramatic struggle with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis had been followed by an anxious public to such an extent that ALS became better and more widely known as Lou Gehrig’s Disease. Christy Walsh, acting as a friend of Mrs. Eleanor Gehrig, paid a call on Sam Goldwyn and settled the rights with him. To Walsh’s mind, Goldwyn had the obvious casting for the Iron Horse in the person of Gary Cooper. The deal seemingly dashed whatever hopes Paramount had in securing Cooper’s services on For Whom the Bell Tolls, as a timely film version of Gehrig’s life would have to be ready for the coming baseball season. Concurrently, there were reports that actor Sterling Hayden would likely be tapped to play Robert Jordan, a bit of news that gained little traction in the press, where items insistently touting Cooper’s eventual participation continued to appear.

As messy as the casting of Kings Row became, the casting of For Whom the Bell Tolls threatened to get even messier. When filming began, neither of the leads had been set, and the search for Maria seemed to be taking on the same monumental proportions as Selznick’s search for Scarlett O’Hara. In October, Goldwyn engaged Howard Hawks to direct the Gehrig story, but having done Sergeant York and Ball of Fire back-to-back, Hawks was physically spent and, in the words of his agent, “didn’t care whether he did the picture or not if he was going to be rushed into it.” Eventually, a complicated deal took shape, wherein Paramount agreed to loan comedian Bob Hope to Goldwyn for two pictures in exchange for Cooper’s participation in For Whom the Bell Tolls. What evidently sealed the bargain was Sam Wood’s willingness to direct the Gehrig story once Bell Tolls was in the can.

Now, with the Hemingway picture on hold, Menzies went straight to work on the Gehrig project, which existed in the form of a draft screenplay by novelist Paul Gallico, the onetime sports editor of the New York Daily News. The story, much of which took place in the looming environs of various baseball stadiums, suggested much in the way of dramatic patterns and interesting compositions, but the script was far from finished, and Goldwyn was wary of a film in which baseball was the dominant factor and not the love story that framed the personal tragedy of Lou and Eleanor Gehrig. There was also another, more practical consideration, which had been noted by Jimmie Fidler as far back as September: “UNHAPPY: Baseball fans and writers are protesting Gary Cooper as Lou Gehrig on the screen because Lou was left-handed and Gary isn’t.”

A low angle contains the figures of Teresa Wright and Gary Cooper, enclosing them with texture and shadow. Menzies frequently took in ceilings in the films he designed for Sam Wood, sometimes for pattern, often for intimacy and containment. (AUTHOR’S COLLECTION)

Cooper, as it developed, wasn’t much of a player, even when using his right hand. “I discovered, to my private horror, that I couldn’t throw a ball,” he said. “The countless falls I had taken as a trick rider had so ruined my right shoulder that I couldn’t raise my arm above my head. Lefty O’Doul, later manager of the Oakland ball club, came down to help me out. ‘You throw a ball,’ he told me after studying my unique style, ‘like an old woman tossing a hot biscuit.’ But we went to work, and after some painful weeks he got my arm to working in a reasonable duplication of Gehrig’s throw. There remained one outstanding difference. Gehrig was a southpaw, and I threw right-handed.”

Lou Gehrig hit and did most other things from the port side, but he wrote with his right hand. Cooper could indeed act him if his playing could be faked, but Menzies wouldn’t abide the old fraud of a double, shot from the rear and matched with finish shots of the lead actor. His compositions, for one, would suffer, and Wood, who had once played semipro ball (and had three broken fingers on his left hand to prove it) wouldn’t hold for it either. Like most of his fixes, Menzies’ solution to the problem was absurdly simple: Cooper would swing and catch right-handed, then they would flip the film in the lab. For such shots as these, Cooper and the other players would be dressed in uniforms on which the names and numbers were reversed, as in a mirror image.

L.A.’s Wrigley Field was where much of the outdoor filming took place, but the minor league ballpark faced northeast, making the position of the sun a big problem. One day they needed a shot of Gehrig running to first base when the baseline was in deep shadow. Forced to improvise, Menzies staged the shot on the third base line, with Cooper running from home to third, then had the film flipped. For the shot to work, the numbers on the backs of the visible uniforms had to be ones, elevens, or eights. The opposing team, Washington, reversed well because of the Ws. Another problem was the wartime shortage of male extras for shots that took in the bleachers, prompting the Screen Actors Guild to grant a waiver that permitted the company to include nonunion personnel in its $5.50-a-day calls for atmosphere players. Augmented with stills and stereos of Comiskey Park and Wrigley Field in Chicago, and stock shots made at New York’s Yankee Stadium, the movie’s fleeting ballpark scenes were thoroughly convincing, owing, in no small part, to the presence of Gehrig’s real-life colleagues on the team’s famed Murderers’ Row—Bob Meusel, Mark Koenig, and Babe Ruth, who drew a $25,000 payday and third billing behind Gary Cooper and Goldwyn contract player Teresa Wright.

Work on For Whom the Bell Tolls was grueling, by far the roughest location shoot for Menzies since The Son of the Sheik. “We climb about all day like Alpinists,” Sam Wood said at the time. “The real heroes are the grip men. They pack heavy lamps and the dead weight of cameras and sound equipment. They string cable from cliff to cliff, mount precipices, and set up block and tackle.” When the company returned to Sonora Pass to complete the bomber footage, there was still snow on the ground. Both Menzies and Wood wore visored caps and, after the first day, covered their noses and lips with camera tape. Still, their faces were raw and peeling when they got back to Los Angeles, and Menzies was so close to snow blindness he had to spend two days in a darkened room. (“With the ointment on,” Wood commented, “we look like Amos and Andy.”) The snow would be gone in July, when they would start making scenes with the principals, but then Wood had a more pressing problem with Sam Goldwyn over the matter of credits on The Pride of the Yankees.

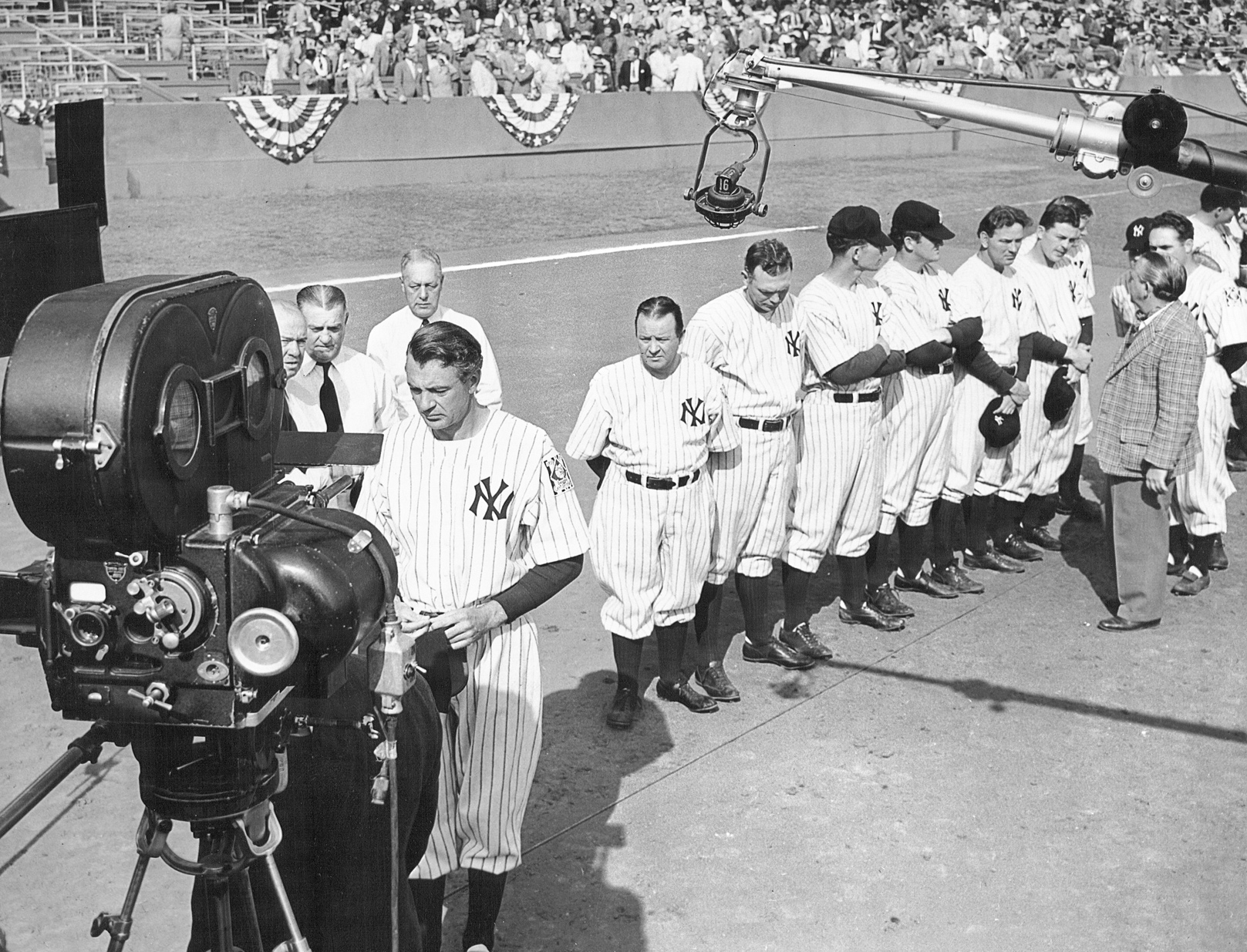

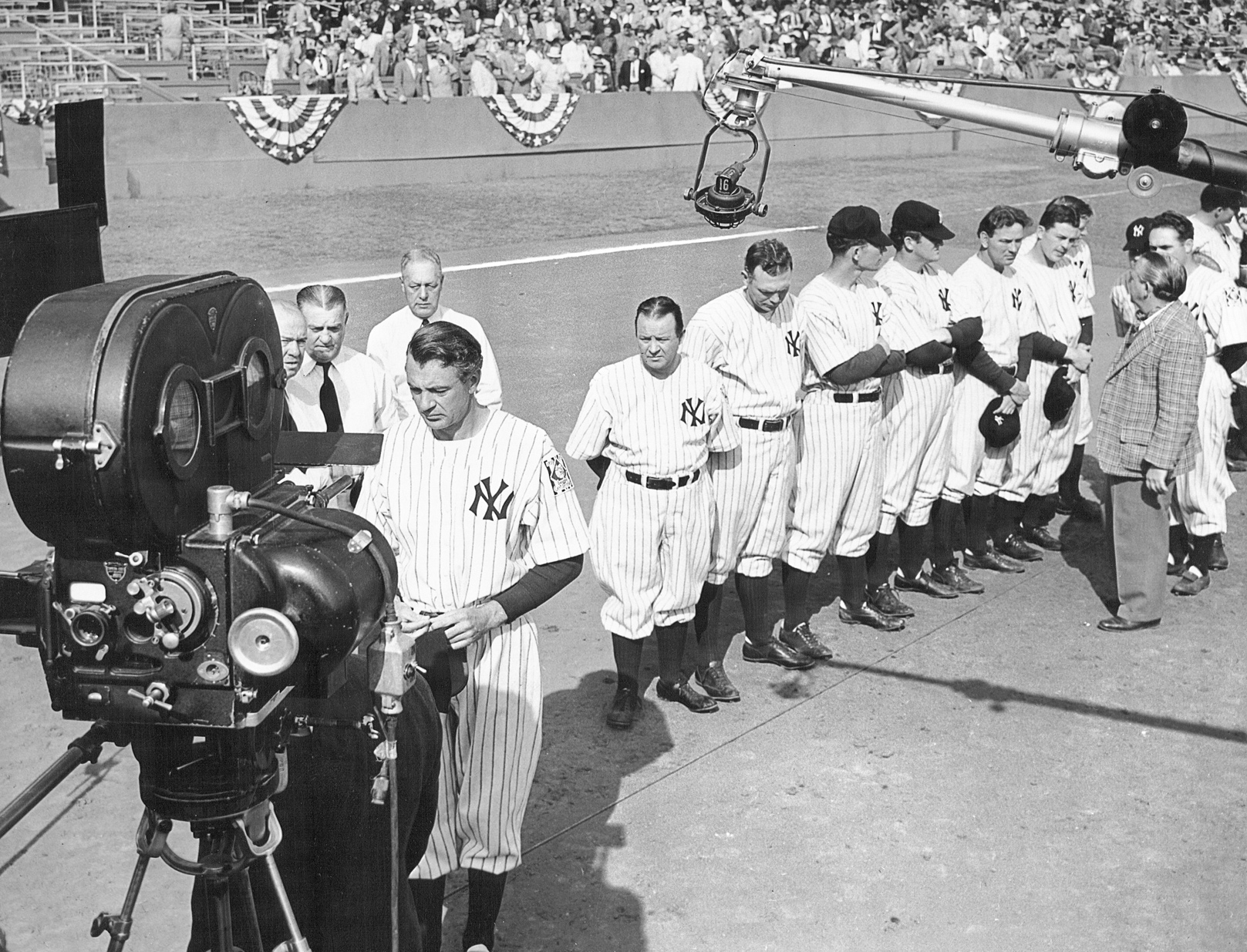

Menzies lines up a shot at L.A.’s Wrigley Field for the Lou Gehrig Appreciation Day sequence in The Pride of the Yankees (1943). Eighteen hundred extras were used for the shots that took in the stands, Gary Cooper in the extreme foreground, the Yankees extending in a diagonal line through the middle distance. “I’ve seen the episode in the newsreels,” Sam Wood said of the event, “and think it is the most dramatic scene I’ve ever witnessed.” (AUTHOR’S COLLECTION)

Goldwyn had balked at giving Menzies a card to himself, saying he had agreed to no such thing and that Menzies could share a card with cinematographer Rudolph Maté. There was, however, an understanding between Menzies and Wood that Menzies would have his own card on each of their pictures together, a matter revisited after Kings Row had been previewed while they were shooting in Sonora and Menzies’ name had been lumped in with four others. “I have been concerned about Menzies’ credit,” Wood wrote in a letter to Goldwyn, “because I have a certain obligation to give him a full card with ‘Production Designed by William Cameron Menzies’ on it. I may not have taken this up with you at the beginning of the picture. Rather than have Menzies disappointed, you may put him on half of my card.”

And so when The Pride of the Yankees had its gala opening the following month, premiering at the Astor Theatre on Broadway and simultaneously playing one-night stands at forty RKO houses in metropolitan New York, the final credit read:

Directed by

SAM WOOD

Production Designed by

WILLIAM CAMERON MENZIES

A stand-up guy, Wood was also acutely conscious of how much he needed Bill Menzies—particularly on a production as vast and as unwieldy as For Whom the Bell Tolls. “Sam leaned on him one hundred percent,” said Ray Rennahan. “Bill designed the costumes, the locations, the compositions. He drew it all out before we ever saw the sets. Of course, we would readjust everything to fit the camera when we could get on them, but Bill designed that picture one hundred percent. All interiors and exteriors and everything else.” Menzies readily acknowledged the fact that his continuity sketches, as thoughtful and as thorough as they were, could express only entrances, first groupings, and finishes, and that it was impossible to plan everything on paper. To keep the action from looking wooden or long scenes from seeming static, there was much to be worked out on the set. “Anytime there was any kind of a question about some particular angle or setup,” said Rennahan, “Bill could take a piece of paper and sketch that off so fast and say, ‘Well, that’s what I had in mind. Can you do that?’ Well, sure I could.”

With Gary Cooper now on board, For Whom the Bell Tolls resumed production on July 2, 1942. A few days later, and under protest from Sam Wood, dancer-actress Vera Zorina, her hair somewhat carelessly cropped to a length of just two inches, arrived at Sonora to assume the role of Maria, a part for which she had vigorously lobbied. “Sam refused to acknowledge her presence,” said Herbert Coleman. “Most of us liked her. She was a lonely figure. She’d come to the location every day but never near the set. We’d see her wandering around in the distance.” After a week of shooting around her, wind and rain hampering his progress, Wood made a single scene in which Zorina exchanged a short greeting with Cooper, sent the film down to Hollywood for processing, then got on the phone and threatened to resign if Ingrid Bergman was not immediately given a test.

Initially, Wood had dismissed Bergman as a “big horse.” He came around after some spirited advocacy on the part of his daughter Jeane, who had read—and loved—the Hemingway book. The matter of Zorina’s haircut had been botched, and Bergman’s own trimming, once given the part, was done under Selznick’s personal supervision. When she arrived on the set, Cooper came down the mountainside toward her. “Hallo Maria?” he said. And at once Menzies gained the most exquisite female face he would ever place before a camera. “He once said that he had always wanted to fill the screen with a woman’s face,” his daughter Suzie remembered, “but until Ingrid Bergman came along, he had never found one that could stand up to such magnification.” Menzies’ close-ups of Bergman—who, incidentally, wore no makeup—were so tight that Ray Rennahan was once heard to suggest, only half jokingly, “Let’s pull back to a long shot now and show the chin and hair.”

They were eleven long weeks on location. In a July letter penciled to his wife, Menzies described his daily routine:

Don’t think I’m complaining too much, honey, but it’s hard to write when your day consists of a little guy calling you out to breakfast at 6:30. Leave at 8. Climb a mountain at 8:30, shoot til 12:30. Climb down the mountain to lunch & I really mean a mountain. Climb back after lunch. Shoot til 6:00 then climb another mountain to pick out the shooting for the next day, to the cabin by seven or 8 or 9. Bath and shave (sometimes) & you have never seen so many rings around a bathtub in your life & so to bed.… Everyone in the troupe except Sam is swell. He is really a pain in the ass. We have yokels who tore up the hill to see the movies & Sam really gets up on top of a mountain & hams all over the place.

There was also the matter of color design for a picture that relied much more heavily on exteriors than had Gone With the Wind. Everyone agreed the location was wonderfully like the Sierra de Guadarrama, the Spanish mountain range where Hemingway’s story was set, except that the California version was considerably greener than the tawny original. Rennahan had filters to knock out the colors Menzies didn’t want, but yellow was difficult and the result on-screen was bilious. Instead, a squad of painters was sent roaming over ten acres, spraying out hot spots on trees and rocks and dusting the landscape with lampblack to bring it more in line with the grim mood of the action. “[The] hillside is bare of green, with fire-blackened pines and harsh rocks,” Sam Wood said of the palette. “If flowers spring up overnight, we pull up stakes and go where it’s bare. Painters spray paint to kill the colors in boulders and trees. For Whom the Bell Tolls has to be in a monotone. Everything looks earth-colored. The only hues are Pilar’s dress, which is dull purple, and Maria’s shirt, which is woodland green. The guerrillas and peasantry look as if they hadn’t washed in years. The fire in the cave, too, also smoked them up.”

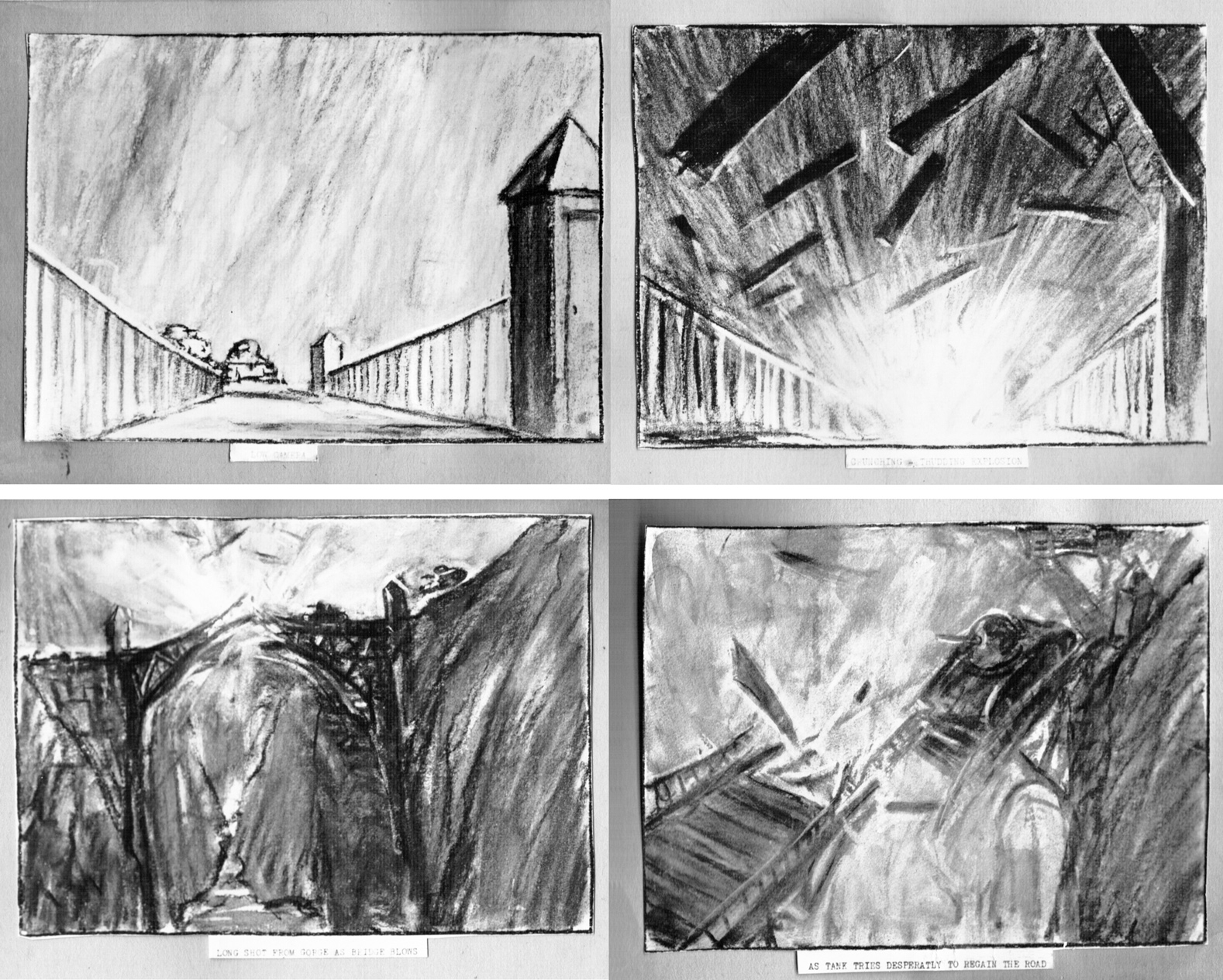

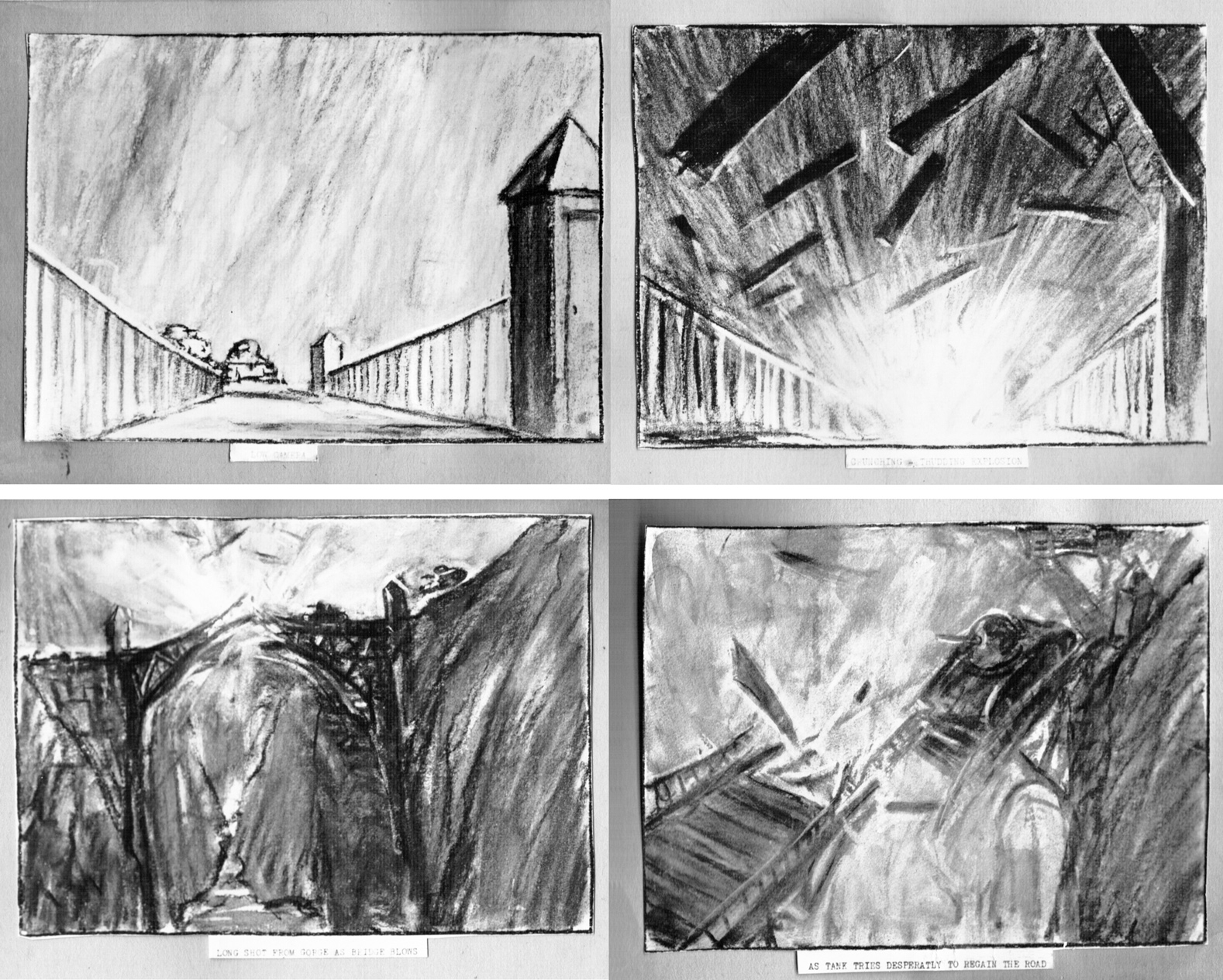

Menzies’ sketches of the bombing of the bridge in For Whom the Bell Tolls (1943). A far less dynamic version, staged in miniature, was eventually used in the film. (MENZIES FAMILY COLLECTION)

It wasn’t always easy for Menzies to get the colors he had designed into the film, even after approving the dailies shipped up from Los Angeles. “It’s almost impossible not to be scenic,” Menzies said, “but we must be powerfully scenic in this film.” Karl Struss, who spent three weeks shooting second unit work with him, lamented a complete lack of control over Technicolor’s fussy processing: “For instance, there was a scene of some prisoners coming out of a dense fog. Well, to put a little color into it, I put a #62 filter over the lights, so to put some warmth into it. This was a flashback, so it didn’t have to be so literal. Well, when I saw the dailies, it looked great; when I saw the finished picture the fog was white. Some guy in the lab with nobody to supervise him thought ‘fog doesn’t look like that’ and did what he wanted. That’s discouraging.”

Some of the men, including Herbert Coleman and assistant director Joe Youngerman, brought their families up for the summer and lived in trailers. Others paired off with the starlets routinely sent up by the studio. “They used to ship them in by the carload,” Suzie Menzies said.

Mother heard about that later; I think [sketch artist] Joe St. Armand told her about that. But I think that’s something you can dismiss. I mean, Daddy was up there for months.… I don’t know that Mother believed that, but looking back on it, she should have. I can remember saying to her, “Why don’t you divorce him?” But she would never leave him because of that. She knew he was having affairs at Universal. And there was one woman—an old friend of hers—who was kind of a constant during Gone With the Wind.… But he wasn’t a flagrant womanizer like so many were. Daddy had a lot of class, but in the movie business, it happens. And it happens to everybody.

Sam Wood had his eye on Ingrid Bergman, but according to Wood’s daughter Jeane, Gary Cooper got there first. “Every woman who knew him fell in love with Gary,” Bergman said. Wood’s younger daughter, Gloria, visited the set and discovered her father had settled on another girl, who remained his mistress for the rest of his life. “It was so primitive and romantic up there among the stars and the high peaks before the winter snows cut off the whole region,” Bergman wrote in her autobiography. “The climate was incredible. We chilled in the morning, sweated in the afternoon sun, and froze at night.” At the end of all that location work, there was another six weeks of interiors to be made at Paramount’s Hollywood studios. Gloria Wood later quoted Gary Cooper on the subject of his luminous costar: “I have never felt so loved in my life—for a short time—then after the picture was over, she wouldn’t even answer the phone.”

Though anticipation for the picture was on a par with that for Gone With the Wind, wartime restrictions on new construction would have made the set-heavy Selznick production impossible in the days following Pearl Harbor. Menzies managed to hold aside enough of the budget to pay for the fabrication of a cave back at the studio. The commodious set, constructed of plaster and chicken wire and roomy enough for a crew of fifty, would permit shots impossible to make on location, where the real cave selected for exteriors proved too small to accommodate two Technicolor cameras, sound equipment, lamps and reflectors, Menzies, Wood, Rennahan, and the company’s four principal players—a group that included Akim Tamiroff and the renowned Greek tragedienne Katina Paxinou.

For Whom the Bell Tolls finished in Los Angeles on October 31, 1942, almost a year after the first shots were made in the snows east of Sonora. As Ingrid Bergman wrote in a letter to Irene Selznick: “I am stunned at the patience, the preparation, and perfection Wood spends on the story.”

Without a break, Menzies went around the corner to RKO, where he would design a Cary Grant vehicle for producer David Hempstead. Mr. Lucky would be Grant’s first picture as a solo attraction after years of being paired with the likes of Katharine Hepburn, Irene Dunne, and Rosalind Russell. Hempstead, who had been Sam Wood’s producer on Kitty Foyle, brought Menzies onto the project with an eye toward mitigating the government conservation order that imposed a $5,000 maximum for new set materials on any one production. With old sets being pulled out and repurposed, he reasoned, how they looked was less important than how they were shot.

New conventions were already in place. Where wallpaper was formerly applied directly to wood surfaces, a layer of cheesecloth now went between the two, making the paper removable and the wall section reusable. Where the average height of a set used to be twelve feet, now they were generally only eight. A section to be burned in a given scene was now made of asbestos instead of wood, the flames supplied by strategically placed gas jets. Even nails were being straightened and used again, cutting the industry’s consumption of new ones by as much as 95 percent. In such an era, Menzies’ bold images, his dialogues staged in silhouette, his tricks with color and lighting made even better sense. His continuities, coupled with more thorough rehearsals, saved much more than the 25 percent reduction in film usage mandated to cover the extra stock needed for training films and other governmental purposes. “I’m a romanticist,” Menzies said at the time. “I was born one and educated as one. But in this motion picture business it’s also essential that I be as practical as a plumber.”

Mindful of all this, Sam Goldwyn signed Menzies to a one-picture contract in January 1943. The project at hand had long been referred to around town as the Lillian Hellman Soviet story. About the time of Menzies’ engagement, it acquired a title—The North Star. The idea of a Soviet documentary was supposedly the brainchild of Harry Hopkins, one of the president’s closest advisors, who favored Lend Lease for the Soviet Union and wanted a film to help soften up the American public. “No matter the different system; that was an internal affair,” screenwriter Walter Bernstein wrote. “The enemy of our enemy was our friend.”

The core creative team was comprised of Goldwyn contract talent: playwright Hellman, director William Wyler, cinematographer Gregg Toland. Over time, the documentary evolved into a semidocumentary and then, ultimately, a big-budget commercial feature. When Wyler accepted a commission in the U.S. Army Air Force, the Russian-born Lewis Milestone took his place. When Menzies signed on, his job, in part, would be to stretch the film’s meager construction budget in the design and fabrication of the Severnaya Zvezda collective, the Ukrainian farming village of the story’s title.

As James Vance, then a twenty-three-year-old sketch artist, recalled, “I was over at Columbia working for several art directors, doing sketches, and I got a call from [art director] Perry Ferguson, who I knew from having worked for Vincent Korda when the Kordas were based at Goldwyn. The war had depleted the ranks of experienced artists and draftsmen, and someone fairly inexperienced, as I was, could get in with someone like Ferguson. So I went over, and we talked, and he hired me. He didn’t say anything about Menzies, but I was in there one day—first week, I think—and he opened the door and said, ‘Jim, I want you to meet Bill Menzies.’ And I nearly fainted.”

Ferguson would be nominated for an Academy Award for his work on The Pride of the Yankees and Sam Wood would draw a nomination in the direction category for Kings Row. And although Milestone had a much greater hand in shaping the script, Menzies was officially associate producer on The North Star, not the production designer. When he did put pencil to paper, it was to rough in a map of the village for Ferguson, who then had it worked out in detail on an enormous drafting board several yards square. As a scale model took shape, the first of some 1,200 continuity sketches were made by Jimmy Vance.

“What I knew about Bill was that he shot low,” said Vance. “So, what did I do? I tried to shoot low. He said, ‘I want this narrow road with a wagon at the end of it, almost at the vanishing point. And I want it surrounded by birch trees.’ And, of course, I said, ‘Where are you going to get birch trees?’ He said, ‘We’ll make ’em.’ So he got cypress and he wrapped them with toilet paper. And he burned the holes. So the first sketch I ever made for him was literally like that—the steppes of Russia and this little tiny wagon. And it gets bigger and bigger until finally the horse comes up and goes underneath us and we’re on two people going to town in this wagon.”

Filming began on March 1, 1943, the face of the Goldwyn backlot having been altered considerably by the removal of the English village square from Wuthering Heights and a Washington intersection built for the Bob Hope comedy They Got Me Covered. The recovered materials went into new facades representing the relatively modern buildings of the collective—a hospital, the radio station, a school—their governmental simplicity contrasting with the thatched-roof peasant cottages in which lived the principal characters. The South Sea lagoon from John Ford’s The Hurricane was leveled and reconfigured into a tributary of the Volga river, and a rail spur—dubbed “the Goldwyn shortline”—was dressed with freight cars similarly hewn from salvaged junk and scrap lumber.

Menzies took an immediate dislike to Lillian Hellman. (“She’s the kind of woman who looks at your fly when you’re introduced to her.”) Hellman, in turn, came to regard him as the most reasonable member of the creative team, someone whose ideas invariably improved the picture. Milestone, on the other hand, submitted fifty pages of suggested script revisions, an affront that prompted her to sever her eight-year relationship with Goldwyn and buy out the remainder of her contract. With a number of minors in the cast, including seventeen-year-old Farley Granger, the film quickly fell behind schedule, many of its actors limited by law to just four hours of work a day. And the film had tonal issues, its idyllic scenes of life in the collective on its final day of peace joltingly at odds with the German air attacks and atrocities to follow. On the sixth day of shooting they were already two days behind, and on the ninth day they were four days behind. By April 1, Menzies was directing a second unit with actors Dean Jagger, Ruth Nelson, and Esther Dale. Augmenting the human players was a menagerie of farm animals—fifty sheep, six horses, six colts, ten head of cattle, two pigs, and the wranglers to keep them in line, dog and bird trainers as well. It soon seemed as if a lot of time went into checking on pigs and dogs.

In July, after a rough cut of the picture had been assembled, Goldwyn decided a critical scene needed rewriting and appealed to Hellman to return to California. Forty minutes into a screening of the assembled footage, Hellman began to cry, softly at first, then hysterically. “You let Milestone turn this into a piece of junk!” she screamed at her longtime employer. “It will be a huge flop, which it deserves to be.”

The North Star finished in October, long after the cast had been dismissed, thirty-five days over schedule and well over its $1.5 million budget. When it was released the following month, critic James Agee judged it “one long orgy of meeching, sugaring, propitiation, which, as a matter of fact, enlists, develops, and infallibly corrupts a good deal of intelligence, taste, courage, and disinterestedness.” As its author so vigorously predicted, it was indeed a huge flop.

As Menzies saw to the filming of The North Star, Sam Wood was making Saratoga Trunk, another picture that starred Gary Cooper and Ingrid Bergman, this time for Warner Bros. Although the movie—at least superficially—looked as if it had been staged by Menzies, the production design was officially the work of protégé Joseph St. Armand. The difference was plain to Eric Stacey, the first assistant on Gone With the Wind, who was now a unit manager under Warner production manager Tenny Wright. Wood, Stacey advised Wright in a memo, was “very vague about how he is going to stage scenes, and after he has done a scene, goes home and sleeps on it, gets another idea and does it again the next day.” Wood was also terribly forgetful, sometimes having to return to a set to pick up a shot he had neglected to make earlier. Said Stacey: “This bears out what I told you at the beginning of the picture—how much he misses someone like Bill Menzies to make up his mind and tell him things.” Under Wood’s direction, Saratoga Trunk finished more than forty days over schedule.

Lewis Milestone, James Wong Howe, and Menzies on the set of The North Star (1943). The artwork in the director’s hand was likely rendered by Jimmy Vance, Menzies’ illustrator on the picture. (ACADEMY OF MOTION PICTURE ARTS AND SCIENCES)

Sam Wood’s daughters both became actresses. Jeane Wood did her work primarily onstage and seemed largely content to be the wife of radio announcer and producer John Hiestand. Gloria, the younger, was more ambitious and decamped to New York, where she changed her name to get out from under her father’s shadow. An admirer of Katharine Hepburn, Gloria appeared in two early film roles as Katherine Stevens. In 1941, she proposed to legally change her name to Katie, then decided a more distinctive moniker would come from simply taking the initials K.T. and forgoing a first name altogether. “It’s just that there are so many Marys, Kates, Joans, Junes, Anitas, Bettys, Helens, Barbaras, and such that I thought I would get me something no one else has used.” Later that same year, K.T. Stevens, twenty-two, made her Broadway debut in George S. Kaufman and Edna Ferber’s oddly pitched saga of generational excess, The Land Is Bright. A few months after the show’s closing, Sam Wood acquired the film rights and entered into a contract with Columbia Pictures to produce and direct it.

Columbia was one of the smaller studios, and its prestige product was usually the result of Harry Cohn, the company’s famously explosive president, affording top-rank directors such as George Stevens and Howard Hawks an unusual degree of latitude. Thus, Sam Wood could cut a deal with Cohn and cast his own daughter in a series of pictures, something he likely would be unable to do at M-G-M or Warners. The understanding called for one picture a year with Wood producing and directing. In May 1943, while Saratoga Trunk was in production, Wood acquired a second property with his daughter in mind, an epistolary novella from 1938 called Address Unknown, a book The New York Times hailed as “the most effective indictment of Nazism to appear in fiction.”

As might be expected, it wasn’t long before Wood invited Bill Menzies into the new venture, handing him a picture to direct for the first time in seven years. “As far as I’m concerned, William Cameron Menzies is entitled to credit as associate producer on For Whom the Bell Tolls, Our Town, Kings Row, and every other movie that we have made together,” Wood told Louella Parsons. Within days, the two men had screenwriter Lester Cole at work on a script, Cole having just written None Shall Escape for Columbia, a prophetic film portraying the trial of a Nazi officer for war crimes. By the end of the month, veteran actor Paul Lukas, who was garnering terrific notices as the idealistic antifascist in Warners’ Watch on the Rhine, had been announced for the lead, and news of K.T. Stevens’ casting had been the top item in one of Hedda Hopper’s columns.

The adding of Address Unknown to Columbia’s program for the 1943–44 season caused Hollywood Reporter columnist Irving Hoffman to ponder the reluctance of producers—many Jewish—to make films depicting the plight of the Jews in Europe. “The answer, of course, is that Hollywood is afraid to. It is afraid to make pictures about Jews, about Negroes, and about other minorities because it might cause a kickback at the box office.” It was not lost on Hoffman that one studio, scrappy little Columbia, was now in the process of making two such films—None Shall Escape and Address Unknown. “From the time Address Unknown first appeared in Story magazine, we have looked forward to its cinemadaptation. Address Unknown has the authority and sincerity of its convictions, and is being produced by a man who possesses those same qualities. He is William Cameron Menzies, whose name wouldn’t cause a ripple among the screen’s cash customers, but he is certainly one of the most important creative figures in Hollywood. We believe Address Unknown has been delivered into the right hands. It is another laborious forward step in the development of that gigantic plaything known as the screen.”

Lester Cole made some essential changes to Kressmann Taylor’s original story, tailoring the part of the doomed Griselle to young K.T. Stevens by making her the daughter of the Jewish art dealer Max Eisenstein instead of his sister. He also added the character of Heinrich Schulz, the son of Eisenstein’s business partner, a gentile, to create a love interest for a tale that otherwise chronicled the relationship of two middle-aged men. The final script came from an unlikely collaboration between Menzies and a freelancer named Herbert Dalmas, whose métier at the time was westerns and serials. As Menzies would later acknowledge, the picture was essentially made on the drawing board. “The whole secret of motion picture making is in preparation,” he said. “What comes after that is hard work.” When production began on November 22, most of the creative effort had already been expended.

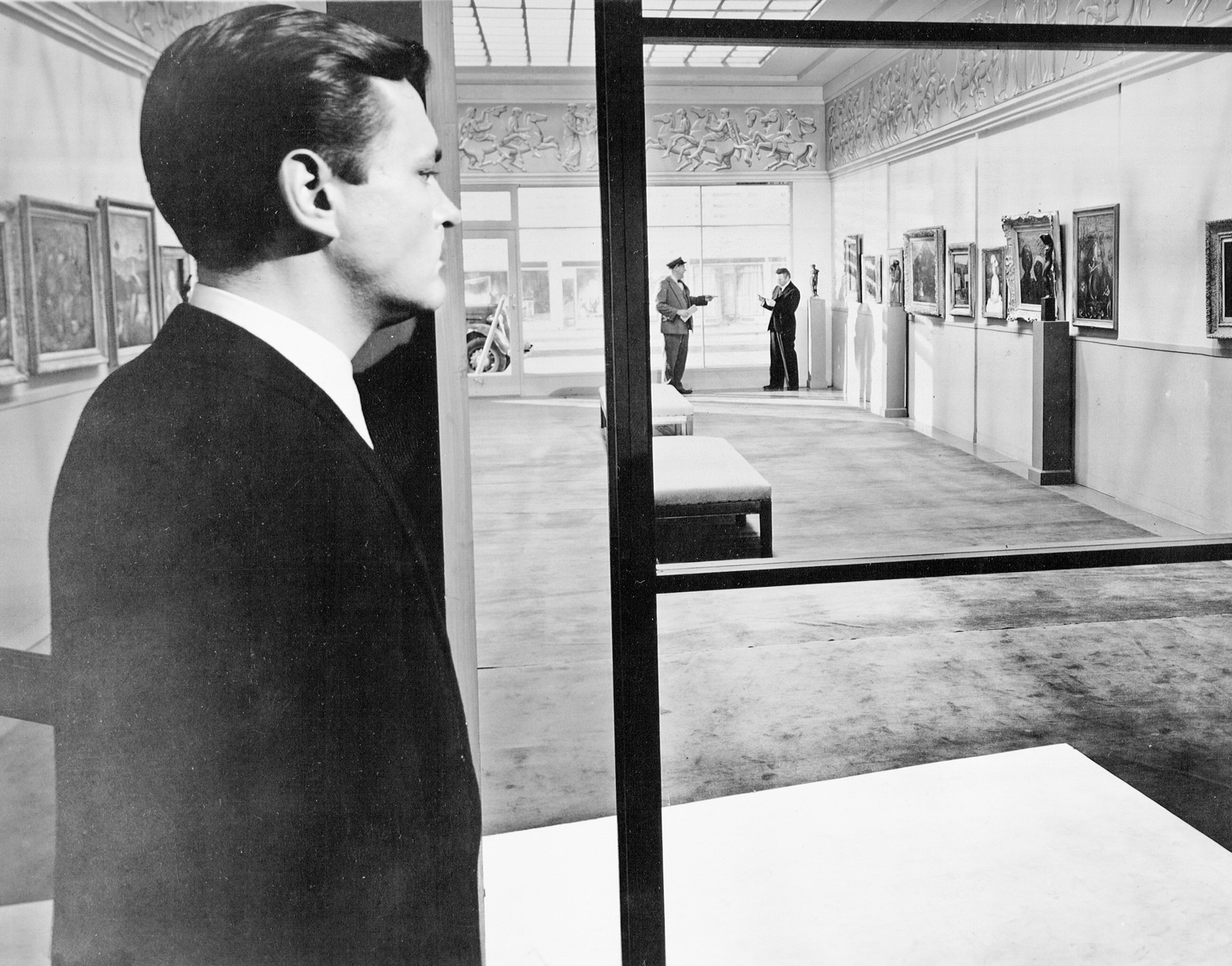

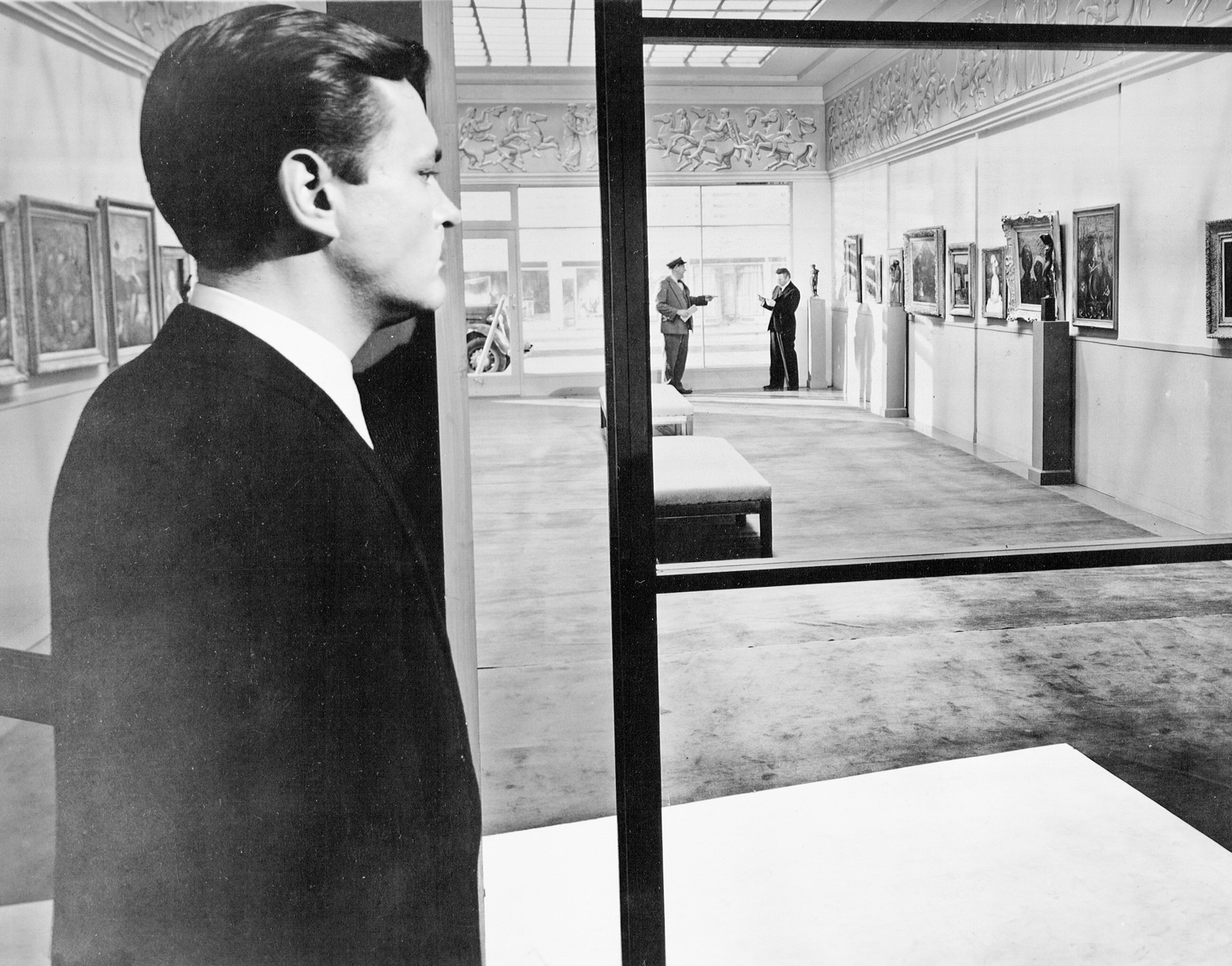

Depth creates opportunities for isolation and emptiness in the Schulz-Eisenstein Gallery, the San Francisco location for Address Unknown (1944). (AUTHOR’S COLLECTION)

Sam Wood came onto the set to pose for pictures with his daughter and actor Peter van Eyck. (“We understand one another perfectly,” Stevens once said of her father.) The first sequence to be shot was Griselle’s Berlin stage debut, where she recites the Beatitudes in defiance of state censorship and is exposed as a Jew to the belligerent audience. She manages to escape, only to have the police catch up with her on the steps of Martin Schulz’s gated house. When he refuses her entry, fearful for his own life and newfound standing with the influential Baron von Friesche, Griselle is brutally murdered by the Gestapo as Schulz listens in a dead panic from the other side of the door, his eyes fixed on a bloody handprint she has left behind.

In staging the pursuit, Menzies vowed he would not highlight the swastika armbands—an overdone device, he felt. He solved the problem by simply giving each man a lantern that could be shined into the lens of the camera, the resulting glare obliterating the familiar symbol of the fascist state whenever it came into view. Though the part of Griselle wasn’t terribly big, it was a meaty one and K.T. Stevens reveled in it. “It was worth waiting five years for,” she said.

Menzies used a sort of conspiratorial shorthand with cinematographer Rudolph Maté, the man with whom he had shot Foreign Correspondent and The Pride of the Yankees. Together they achieved a stark, unsettling look for the picture, with solid blacks and desperate, unforgiving whites, Griselle’s costume glowing like a flame in the dark alleyways of Berlin, the angry mob stalking her only yards away, the graphic tension accentuated by forced, violent perspectives that gave the picture a nightmare quality. “He knew so much about black and white and the use of mass,” said Jimmy Vance. “If something needed to be dark, he would have the decorator bring in a big black case.”

Armed with some eight hundred continuity sketches, Menzies moved the film along at an admirable pace, keeping the entire enterprise on schedule and under budget. “He was a very professional man,” said Richard Kline, the movie’s seventeen-year-old camera assistant. “I know that he and Rudy Maté had a very close relationship. It was really a film that went off very smoothly, with no interference.… I don’t recall any problems at all with the film, other than it being a smooth operation.”

The spatial distances between characters inform the compositions in Address Unknown. At Munich, Martin Schulz (Paul Lukas) urgently seeks the approval and friendship of Baron von Friesche (Carl Esmond), a well-connected nobleman who disapproves of the Jewish girl engaged to Martin’s son.“You are going to have to choose, Herr Schulz,” the baron tells him. “You cannot sit on two stools at once—at least not here in Germany.” (AUTHOR’S COLLECTION)

Address Unknown wrapped on January 13, 1944. After putting it before a preview audience, Menzies rewrote some scenes to expand the role of actor Carl Esmond, who had been borrowed from Paramount to play the sinister Baron von Friesche. With retakes done by the end of January, the picture was ready for its New York opening on April 16, scarcely a month after Paul Lukas scored a surprise win as Best Actor for Watch on the Rhine. The critical reaction was terrifically positive, with both The Hollywood Reporter and Daily Variety posting rave reviews.

“William Cameron Menzies,” led the Reporter, “offers in Address Unknown a beautifully-made picture which fairly glitters with brilliant performances, led by Paul Lukas in an unforgettable portrayal and lovely K.T. Stevens, whose delicately sensitive interpretation of her first important role marks her for stardom.” Daily Variety declared the feature a “notable success” for Menzies after years as Wood’s associate. “He builds up his situations shrewdly and handles them with an appreciation of highest dramatic values, the result being Address is a carefully contrived production of distinction.”

In New York, the Times’ Thomas M. Pryor affirmed that Address Unknown, given its only minor liberties, lacked “none of the punch” of the original story. “The tragic atmosphere of the picture has been heightened through the brilliant use of low key lighting effects by William Cameron Menzies, the director, who is better known as Hollywood’s leading production designer. Mr. Menzies, cloaking the greater part of the story in deep, brooding, shadowy photography, methodically builds the tension into one of the most spine-chilling climaxes you’ll encounter in many weeks of moviegoing.”

Columbia set a May 6 opening for Address Unknown in fifty-one cities, and after a decidedly checkered career as a director spanning fifteen years, Menzies finally found himself the author of an unqualified critical success. (“Apparently,” wrote Philip K. Scheuer, “he is one of the few pictorial craftsmen left in Hollywood—and not ashamed of it.”) Yet after striving for the very position in which he now found himself, Menzies was ambivalent and unsure if he really wanted to continue on the course that was now finally open to him. He talked wistfully of returning to England after the war and opening a pub on the outskirts of London, something he had been saying since before the attack on Pearl Harbor. “To tell the truth,” he said in an interview with the magazine U.S. Camera, “I’m not overly fond of directing. In the first place, I’m inclined to be lazy. I don’t like getting up at dawn in order to be on the set well ahead of everyone else and getting the day’s work lined up.… I imagine I get just as much pleasure out of my work as does any painter or sculptor, but I just don’t know how to take this business of being a director.”