CHAPTER 1

People live here on purpose; that’s what I’ve heard. They even cross the country deliberately and move in to the neighborhoods near the river, and suddenly their shoes are cuter than they are, and very possibly smarter and more articulate as well, and their lives are covered in sequins and they tell themselves they’ve arrived. They put on tiny feathered hats and go to parties in warehouses; they drink on rooftops at sunset. It’s a destination and everyone piles up and congratulates themselves on having made it all the way here from some wherever or other. To them this is practically an enchanted kingdom. A whole lot of Brooklyn is like that now, but not the part where I live.

Not that there isn’t any magic around here. If you’re dumb enough to look in the wrong places, you’ll stumble right into it. It’s the stumbling out again that might become an issue. The best thing you can do is ignore it. Cross the street. Don’t make eye contact—if by some remote chance you encounter something with eyes.

This isn’t even a slum. It’s a scrappy neither-nor where no one arrives. You just find yourself here for no real reason, the same way the streets and buildings did, squashed against a cemetery that sprawls out for miles. It has to be that big, because the dead of New York keep falling like snow but never melt. There’s an elevated train station where a few subway lines rattle overhead in their anxiety to get somewhere else. We have boarded-up appliance stores and nail salons, the Atlantis Wash and Lube, and a mortuary on almost every block. There are houses, the kind that bundle four families close together and roll them around in one another’s noise as if the ruckus was bread crumbs and somebody was going to come along soon and deep-fry us. Really, it’s such a nothing of a place that I have to dye my hair purple just to have something to look at. If it weren’t for those little zigs of color jumping in the corners of my eyes, I might start to think that I was going blind.

It seemed that way even before the nights started lasting such a very, very long time.

We can’t prove it. By the clock everything’s fine. The sun goes down around seven p.m. these days, right on schedule for your standard New York April, and comes up at six the next morning. The effect was so sneaky at first that it was months before anybody worked up the nerve to say anything. Then, maybe around November, I started hearing discreet wisecracks, muttered like they were something embarrassing, like, “Hey, Vassa! Long time no see!” when I walked into school in the morning. But winter was coming on then, anyway, so you could tell yourself that, hey, the nights are supposed to feel long now.

By January, though, it was getting harder to ignore. It gets to the point, when your whole family is waking up around two a.m., and eating cereal, and shuffling around, and watching a lot of old movies, and then it’s still only three thirty so you all go back to bed, where you might kind of mention that it seems a little unusual. And when it gets to be February, then March, and the nights are officially getting shorter but everyone can feel how they drag on and on, the hours like legless horses struggling to make it to the end of the darkness, then you might even start to complain. You might say that the nights feel like they’re swallowing your drab nowhere neighborhood and refusing to cough it back up again the way they ought to. And the more the nights gobble up, the bigger and fatter and stronger they get, and the more they need to eat, until nobody can fight their way through to the next dawn.

I’m exaggerating. Morning does always come around eventually. At least, it does for now.

See, to whatever degree we have magic around here, it’s strictly the kind that’s a pain in the ass.

So it’s the middle of the night—unprecedented, I know—and the kid upstairs is practicing skateboarding on some kind of janky homemade half pipe and wiping out at ten-second intervals and I’m watching a random black-and-white movie with the girls people call my sisters, though they’re sisters step and fractional. I forget, but I think Chelsea is step-half and Stephanie is third-step once removed, or something like that, or possibly it’s the other way around. Whatever they are exactly, they’ve been assigned to me by the twitching of fate, and they’re usually at least plausibly sister-esque. We even share a bedroom. The woman who it’s fair to assume must have given birth to at least one of us, but by no means to me, is off at the night shift at the pharmacy where she works in Manhattan. Seems awful to be stuck with the night shift now, but she says it’s not as bad there. She says people barely notice the difference yet in Manhattan. She says they can afford all the day they want. Maybe they’ve found some slot where you can stick a credit card and order up a new morning.

Steph whirls in with a bowl of microwave popcorn and sets it on the bed between her and Chels. She scowls a bit when I come crawling across their pink-fleeced legs to snag some, piling it on the back of my chemistry textbook and then carrying it to my own bed. However carefully I balance, there’s a fair amount of drift over the book’s sides. Popcorn is hardly ideal, too noisy, but it’ll have to do.

It’s a rotten movie for my purposes. Ingrid Bergman is kissing somebody. Personally I prefer guys who are less gray, though I guess she’s in no position to be picky. “Let’s watch something else.”

“Shut up, Vass. It’s almost the end!”

“Then you won’t be missing much, right?” But there’s no hurry. They’ll put on something nice and loud eventually. There’s a lot of squirming in the pocket of my sweatshirt and I cover it with my hand. Tiny teeth nip at my thumb, though the thick fabric keeps it from hurting much. So impatient.

Static abruptly drowns out Ingrid, forcing the issue. That happens a lot these days and then there’s nothing to do but change the channel, which Stephanie does after casting a scowl my way. Just because it’s convenient for me doesn’t make it my fault.

The next movie is tenderly devoted to chasing and shooting and blasting. When the first car goes up in a fireball I slip a puff of corn into my pocket and then start crunching loudly myself for good measure. Chels and Steph don’t seem to notice. They’re mesmerized by the flashing lights. I can hear it, though, the shrill styrofoamy nibble-squeak from my pocket. I can feel the slight vibrations against my waist as she chews. A tiny fist prodding my guts. Erg wants more. Such a little thing, but she never stops eating, and why should she? When you’re carved out of wood you never gain weight. I’ve seen her gnaw through a candy bar bigger than she is in two hours flat. I’ve seen her actually burrow under the crispy batter on a chicken leg and then pop out near the bone, leaving the skin sagging into the tunnel left by her mauling.

Erg and I have gone on this long without Chels or Steph or anyone getting wise to her. My sisters think I’m the greedy one, always stashing cookies in my pockets for later. They think I suffer from strange compulsions. All my clothes have grease stains on the right hip. Sometimes I get sick of how demanding she is. Sometimes I’ve even toyed with the idea of letting her go hungry for a few days, or even not feeding her again. She’d complain at first but eventually, I’m pretty sure, she’d just go back to being inanimate.

Instead I stuff a whole handful of popcorn in. No matter what I pretend, I’ll never actually starve her, and she knows it. She’s the only thing I have from my mother so there’s nostalgia working in her favor, and then I made a promise.

Little crunching noises squeak from my pocket. I’m way ahead on my reading for school, we all are—Chels has already moved on to college math and science textbooks, just to have something to do—but I get out Great Expectations anyway and try to concentrate.

In the window it’s night, with cottony puffs of light clinging to the streetlamps. In the window there’s no hint of dawn. It’s been 4:02 a.m. for an astoundingly long time. Then 4:03. Progress!

I look up at the TV for a moment to see a girl with big curls and a plaid cap walking past shuttered stores. The street is dark and she jumps as a rat skitters over her boot. She looks lost and lonely, hunching her shoulders to hold off the night. Then a tide of light washes her face and she looks up in rapture to see a BY’s. Wow, you can see her thinking, it’s still open! The store dances and spins and as the girl pirouettes ecstatically more BY’s stores appear around her, and more, all dancing on spindly legs of their own, until the whole dark night gets crowded out by the flash of their windows. “Turn around,” the girl sings. “Turn around and stand like Momma placed you! Face me, face me!”

We’ve all seen this ad a million times, of course. None of us can be bothered to make snide remarks anymore, or to mention that they left out the all-important ring of stakes skewering rotting human heads. All the mockery we could possibly mock is too done and too obvious and wasn’t really all that funny in the first place. We used to sing, “Turn around. Turn around and run the other way! Chop me, chop me!”

We don’t bother. Maybe it means we’re getting old. Maybe the nights are so long now that we’re only superficially kids, and we’ve lost years to the darkness.

Steph suddenly puts a hand to her throat and lets out a gasp.

“What?” Chelsea asks her. “You lost your locket?” She shoots me a significant look. The slight squirming in my pocket stops dead.

“I was wearing it! I hope—maybe I just knocked the clasp open?” Steph starts ransacking her pillows.

“It will show up soon, I’m quite sure,” Chelsea says, taking time to enunciate each word, and arches her eyebrows my way.

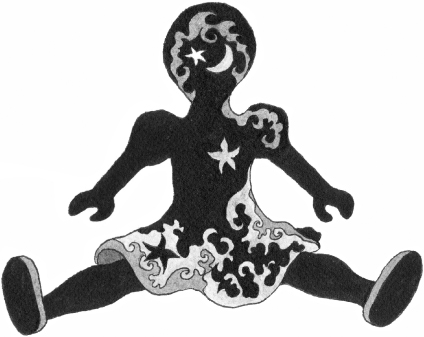

I excuse myself to the bathroom and perch on the toilet lid. The bathroom is bright pink, with this cheesy mermaid wallpaper Steph picked out when she was five; the shower curtain is stained with garish purple streaks from my hair dye. I can feel the lump in the pocket of my hoodie but it’s as still as a wad of used tissues. Erg is pretending to be asleep. I get her by one tiny wooden foot and drag her out anyway. She dangles upside down, her eyes closed, her painted black hair gleaming in its flat spit curls. She doesn’t react when I drop her in the sink, which is enough to prove that she’s faking.

I turn the water on full blast. I’m not a kleptomaniac, really. I just harbor one. Erg leaps up sputtering, water sheeting off her spherical head. Her feet clop on the pink porcelain as she leaps around but the sink is too slippery for her to climb out; she’s lacquered so she doesn’t have much traction. She lands on her carved blue rear, legs clacking. “You turn that off! Vassa! You’d better stop!”

“Are you going to give the locket back?” I’m not going to yield quite so easily. I’m sick of getting blamed for Erg’s lousy behavior.

“Probably. Eventually. If you don’t do anything to provoke me in the meantime.”

I reach toward the knob that lowers the stopper into place. “How about you do it tonight? You can put it in her bed. So there’s at least some plausible deniability in regard to my being a thieving psycho?”

Erg squeals and snaps her legs closed, wedging her feet below the metal disk that stoppers the sink. I could just pull her out of the way, though. Being fierce doesn’t get you too far when you’re an imposing four and a half inches tall. “You wouldn’t dare!”

“Oh, Erg,” I say. She reminds me of my mother more than I like to admit. “Just quit the damn stealing and we won’t have these problems. Okay? Say you’ll put it back tonight and I’ll dry you off.”

“And oil me?”

I turn off the tap. No matter how mad she makes me, Erg is still my doll. Her painted lashes flick up and down, batting droplets out of her flat blue eyes. “Sure. Just put it back.”

“You’re going to ruin my finish if you keep doing this,” Erg complains. “I might even split.” She waits for me to pick her up, buff her in a warm towel. Instead I stare at her. I know her ways. “I’ll slide it in her bed tonight, and she won’t have any reason to accuse sweet Vassa of doing anything untoward, okay? Okay?”

I pick her up between my thumb and forefinger and wrap her in a hand towel. She’s a pretty thing with her swooping violet eyelids and tiny ruby mouth, her thin arched black brows and perfect curls. She has a carved wooden dress, sky blue with white painted loops standing in for lace at the collar and cuffs. Her exposed skin is just varnished pale wood, then her legs end in white socks with more of that curly trim and black Mary Janes, all painted. Her knees, elbows, and waist are jointed and she can pivot her head. Nice workmanship. Too bad they didn’t spend more time on her personality.

In spite of myself, I kiss the top of her shiny head. She tries to bite my lip, but I yank her back in time and her little wooden jaws snap on empty air.

When I said that magical things in Brooklyn should be shunned like the plague? I’m sorry to say that’s not always an option. I was leaving Erg out of the equation although, with her being a talking doll and everything, she’d be magic by anyone’s standards. I don’t have much chance of avoiding her, since we’re bound to each other for life. And no, I didn’t name her that. It’s what she calls herself. When I was younger I tried to get her to accept names like Jasmine or Clarissa but she wasn’t having it.

I plonk Erg down on my lap and get out the bottle of lemon oil from under the sink. It’s her favorite and I always try to keep some around. Dab the oil on some toilet paper and give her a nice rub-down, working it up and down her limbs while she makes little purring sounds. Getting oiled makes her sleepy and she rolls on my black flannel pajamas and rubs her face against me like a kitten. She can be cute sometimes. She’d better be cute, really, considering all the trouble she causes.

“You don’t like Stephanie anyway,” Erg murmurs. “She’s kind of a bitch.”

“I like her fine,” I say. “You need to quit projecting.” Erg snuggles into the folds of my pajama leg, yawning and wrapping her tiny arms around the loose fabric. By the time I slip her back into my pocket she’s fast asleep.

When I get back to the bedroom Chels and Steph are both glowering at me like they have synchronized brain waves. “You were gone a while,” Chels observes coolly.

“What?” I say. I’m still standing against the door. “Like two minutes?” We all know how meaningless minutes are now, at night anyway. “Did you find your locket, Steph?”

“Yeah,” she says, then pauses. “I did.”

“So where was it?” I try to sound uninterested.

“In your shoe. One of the ones with the spikes.”

My guts tighten up just a bit. “Weird.”

“Under your bed.”

“Double weird.” Erg will be lucky if she eats again this week.

“You think that just because you can get away with murder with boys, you can mess with me, too? My mom gave me that locket, Vassa!” Maybe that’s why Erg was attracted to it. Another mom-present, like she and the locket could be comrades and start an insurrection.

“I didn’t touch it,” I say. But this is one of those times when truth is utterly worthless. They won’t stop scowling.

“Vassa,” Chelsea hazards, “if you won’t admit you have a problem then there’s no way we can even try to help. You’re basically our sister, and we both really want to be able to trust you. Right? And you’re a great person, but you have this serious issue which is making everyone feel like you’re bad news to be around. I am saying this,” she adds carefully, “out of love.”

“I appreciate the love part,” I tell her. “But I didn’t do it.”

“Then who did?”

I can’t answer that, is the problem. Everything would be so much simpler if I could just tell them the truth, and I want to. I could pull Erg out of my pocket and let her take some responsibility for once. But, well, I promised my mom, an hour before she died, that I would keep Erg completely secret forever, and feed her and take care of her, and—like three more times—that I would really, truly never tell anyone. I don’t want to lie to Chelsea, though. “Not me. That’s all I can tell you, Chels. Okay?”

“Very not okay.” Chelsea is nobody’s fool. She has huge dark eyes that could make anyone feel ashamed. “Very, extremely not. When you decide you’re ready to try some honesty, V., you let me know.”

Since there’s nothing else to say I go to my bed and curl up with my book. They both keep watching me to see if I’m embarrassed yet, which I am, so I turn my back. In a way it’s my fault that this keeps happening. If Erg can’t control herself, then it’s my job to keep her in line. I start thinking about those metal key chains that snap shut. Maybe Erg is going to get one installed around her neck, though I’m not sure if there’s a way I can attach the other end inside my pocket that she won’t be able to undo. Her hands are shaped like mittens with nothing but thin lines to show the separations between her fingers, but she does have opposable thumbs and she can work them like a fiend. You’ve never seen a human being with hands that quick and sly.

Maybe Stephanie dozes off at some point, because a while later I feel my bed sinking behind me. I roll onto my back and Chelsea is there, looking down at me with concern. “Hey,” she whispers, “I can understand if you don’t want to talk about it in front of Stephanie, V.” I just look at her. She’s trying to be sweet but there’s nothing much I can say. “Look, okay, I have a theory, Vassa? That you’re compensating for your parents being gone by stealing things that represent the love you deserve? Symbolically? And you’re right, you do deserve that love, but I’m just trying to tell you that this isn’t the way to get it. Nothing you take can make up for your mom dying or your dad being … away.”

None of us ever say directly what happened to him. The facts of the case just howl for euphemism.

“I know that,” I tell her. “Chelsea, look, I really do appreciate what you’re trying to do, or what you think you’re doing, but I’m not going to confess when I didn’t take the damn locket!”

“A present from our mother? When you lost your mom? Really?” She does a fantastic job of loading every syllable with significance. “Anyway he’s Steph’s dad, too. It’s not like you’ve got some special relationship with tragedy. Do you ever think about how all of this affects her?”

Maybe not. I maybe tend to repress the reality that Steph and I share a father.

“Not when I’m trying to read,” I tell her.

Chelsea sighs. “I’m here whenever you want to talk. Just think about what I’m telling you. Please?”

She gets up again, but she’s only going back to her own bed a few feet away.

I’ll try to break it down for you. Chelsea and Stephanie have the same mother but different fathers; Steph and I have the same father but different mothers; Chelsea is oldest, Steph is second, and I’m the youngest, but only by a week; and yes, that means my dad got both our moms pregnant at almost the same time, maybe on the same night for all I know. He spent the next ten years going back and forth between them, depending on who made him feel guiltiest, I guess, and then my mom considerately died and simplified his decision-making process. So he married Iliana, making her actually my stepmother for all of five months, and then bailed on all of us in dramatic style.

In consequence of our scrambled parentage we’re all different colors: Chelsea is chestnut brown, Stephanie is kind of beige, and I’m almost disturbingly pale. If I didn’t dye my hair I’d look a lot like a human version of Erg, all blue eyes and raven tresses. Chelsea is the smartest, due to get the hell out of here in September on a full scholarship, assuming September ever comes that is, Stephanie doesn’t have two brain cells to bang together, and I get by. So Chelsea and I aren’t actually blood but she more or less considers me a sister, and we might even love each other most of the time, but Steph, who is related by blood, definitely thinks of me as an interloper, and we maybe hate each other just a microscopic bit, though sometimes we have fun anyway.

If all of that sounds messy, well, it surely is, but to put it in perspective there are plenty of things that are messier. My own emotions, for example, which could make a city dump look like a library. And the big blue world outside of our apartment is messier and grubbier and more chaotic than anything we’ve ever personally come up with.

I say that with complete confidence.