CHAPTER ONE

SHE USED IT AS A DOORSTOP

THE TROPHY THAT Jay Berwanger wanted shares shelf space in the archives room of the College Football Hall of Fame in downtown Atlanta, sitting nearby a portrait of Desmond Howard, a bust of Woody Hayes, and a plastic wig of Brian Bosworth’s mid-1980s Mohawk/mullet (yes, they made Boz wigs).

The Silver Football, awarded by the Chicago Tribune to the Big Ten’s Most Valuable Player (though, in those days it was deemed “the most useful player to his team”), was eleven years old when the Chicago Maroons running back entered his final season in 1935.

“The Tribune award made me happier at the time,” Berwanger said fifty years later. “That was established, well known.”

The Heisman Trophy wasn’t. In fact, it wouldn’t carry that name until its namesake, John Heisman, died months after Berwanger received the Downtown Athletic Club Trophy in 1935.

But while Berwanger’s Silver Football has yet to see the exhibit floor in the HOF since it relocated from South Bend in 2014, his Heisman sits in the foyer of the Gerald Ratner Athletics Center—a $51 million, 150,000 square foot facility at the University of Chicago that opened in 2003. Encased in glass, it is displayed under the center of the rotunda, and expectedly, it has a tendency to steal attention.

Cuyler “Butch” Berwanger, Jay’s youngest son, was on campus with friends when a group of prospective students and their parents entered the facility with a tour guide.

“She says, ‘Here we are at the Ratner Center’ … and before she can even say the word ‘Heisman,’ all these people walked past her and they went right up to it,” Berwanger said. “[The tour guide] said, ‘This happens every time.’”

For years, though, that trophy lived a life that was far less spectacular.

When Berwanger returned with the DAC award from New York, where he lugged around the trinket (unlike the modern-day version, which has a wooden base, the original sat atop black onyx marble, making it upwards of forty pounds), he had no clue what to do with it.

There was no suitable place for it in his small room in the Psi Upsilon house, and it became a nuisance as Berwanger attempted to study for exams. So he called his Aunt Gussie, who lived on the north side of the city, and asked her to keep it.

But Gussie didn’t have a mantelpiece to display the hefty, stiff-armed award. She instead found a more practical use for it.

“She kept it in the hall on the floor and discovered it could be used as a doorstop,” Berwanger said in 1990. “It was a very logical thing to do.”

****

Even when Berwanger graduated and married his first wife, fellow Chicago alum Philomela Baker, in 1940, he still didn’t reclaim his prizes.

The DAC trophy would serve in its capacity at Gussie’s for fifteen years, and when Berwanger would visit “I’d toss my hat over it,” he said.

Eventually, the award, along with the aforementioned Silver Football, newspaper clippings, and one of Berwanger’s uniforms, were packed away and placed into a trunk that sat in her attic.

“Really, when we first moved to Hinsdale [Illinois] in 1950, there was nothing in the house that represented the fact that he won the Heisman Trophy or was All-American or captains of All-American teams or anything else,” said Butch Berwanger.

It wasn’t until a few years later that Butch, who estimates he was seven at the time, was even aware that his father had been the first winner of college football’s most coveted award.

His brother, John Jay—who is three years older—came home from school and Butch heard him tell their mother, “One of the teachers had said ‘Oh, Berwanger. Your dad won the Heisman Trophy.’”

“Who won the Heisman Trophy?” John asked.

“Well,” their mother replied, “your dad won it.”

He hadn’t, to Butch’s recollection, ever mentioned it before. Not once.

Even when the trunk made its way into the family’s home, the DAC trophy was either in the basement or in the attic, never displayed ostentatiously.

“That was my dad,” Butch said.

****

One of five children of an Iowa blacksmith and farmer, Berwanger’s path seemed set. He would complete the industrial track at Dubuque High School, then become—more than likely—a mechanic or something of that nature. But his exploits in wrestling, track, and football changed that.

He competed at the state championships in track and wrestling, and in football he starred as a halfback, linebacker, punter, and kicker. In the final game of his high school career, Berwanger was responsible for all the scoring in Dubuque’s 20–0 win, with three touchdown runs and two extra points.

Michigan came calling. So did Minnesota and Purdue, and in-state power Iowa. But Chicago never did.

Local businessman Ira Davenport would play a part in Berwanger landing with the Maroons, as did, inadvertently, Hawkeyes coach Burt Ingwersen.

Davenport, the owner of Dubuque Boat and Boiler Works (he was also a bronze medalist in the 800-meter run in the 1912 Olympics and former football coach at the city’s Loras College), had hired Berwanger for a summer job. A product of the University of Chicago himself, Davenport took Berwanger to the campus twice, where he met track coach Ned Merriam—another Olympian from the 1908 London Summer Games—and members of his future fraternity.

“Before I knew it, things fell into place and the university offered me a scholarship,” Berwanger told the Chicago Tribune in ’97. “I was seriously thinking about a career in business, and I thought I could make more contacts in Chicago, compared with a small town like Iowa City or Ann Arbor, Michigan. Plus, I was excited about the University of Chicago’s academics.”

He was also turned off by a speech that Ingwersen gave while speaking to Dubuque High School’s football banquet during Berwanger’s senior year in which he told the players they were traitors if they left the state of Iowa and went to another school.

“My dad just didn’t like that,” said Butch Berwanger. “He didn’t like the pressure of having to go to an Iowa school because you were from Iowa.”

Berwanger was given a full-tuition scholarship of $300, but he would still have to pay for his room and board, which forced him to work in the school’s engineer department, cleaning the gymnasium, fixing toilets, and running elevators, to meet his financial needs.

“Times were tough then,” he said in 1986.

He had expected to play for future Hall of Famer Amos Alonzo Stagg, who had been in charge of Maroons athletics for more than four decades. But during Berwanger’s freshman year (at the time, first-year players weren’t eligible to play at the varsity level), Stagg was forced to retire. He had turned seventy on August 16, 1932, and in October of that year, the school had invoked a rule that provided seventy was the age limit for members of the faculty.

In announcing the retirement of Stagg, who had a .617 winning percentage, seven Big Ten titles, two national titles, and eleven consensus All-Americans to his credit, Chicago’s board of trustees said it had created a new job, chairman of the Committee on Intercollegiate Athletics, for the outgoing coach. Instead, Stagg left to take over at Pacific.

“I’m going west and feel like I’m twenty-one years old instead of seventy-one,” Stagg would say. “I’m ready to start another career and am as happy as can be.”

Athletic director T. Nelson Metcalf turned to Clark Shaughnessy, who had success at both Loyola of the South and Tulane. The brain behind the modern T-formation, though he would never use it at Chicago given his personnel, was lured by the chance to coach in the Big Ten.

He was hired as coach and physical education professor, which enabled him to receive lifetime tenure (since all Chicago professors received it) and a $7,500 annual salary. He also inherited a player in Berwanger, whom he would give number 99. “That was as close to a perfect 100 as I could get,” Shaughnessy said.

****

Nicknamed Genius of the Gridiron, the One-Man Gang, and the Flying Dutchman (despite his German lineage), Berwanger was on the field as a halfback/receiver/defensive back/kicker for every play in Chicago’s five conference games of his sophomore year.

A year later, in 1934, Berwanger was also playing quarterback and scored 8 touchdowns on 119 carries, completed 4 passes for 196 yards, had 186 yards on 18 punt returns, and totaled 3,026 yards on 77 punts. Against eventual co-national champion Minnesota, Berwanger had 14 tackles—in the first half.

“I have never met a finer boy or better football player than Jay Berwanger,” Shaughnessy said. “You can say anything superlative about him and I’ll double it.”

Adding to the fact that at 6-foot, 195 pounds he often weighed more than any other player on the field, Berwanger wore a white single bar across his helmet. It was a necessity to protect a nose that had been broken in his final high school game and again during his freshman year, but it gave writers another nickname for him: “The Man in the Iron Mask.”

“I was told if I broke it again, I wouldn’t have any nose left to repair,” Berwanger said years later.

During his junior year, Berwanger led Chicago to a 21–0 win over Indiana that had it, for the time being, atop the Big Ten standings. He had a 97-yard kickoff return for a touchdown and threw for a 40-yard score to John Baker, and the only points he wasn’t responsible for were because of a safety that came after he had taken a seat on the bench in the third quarter.

Red Grange, the legendary Galloping Ghost, was on hand at Stagg Field that day in the press box. As the former NFL halfback told reporters, “[Berwanger] looks more like a real ghost to me, running through the rain and mud with that white mask on.”

Five days later, the syndication service Newspaper Enterprise Association published a column by Grange in which he wrote, in part, about the attributes that make the perfect running back: a “faraway look” or field vision that allows a back to run at full speed, plant, and cut without altering pace; the power to run through the line; and constant speed. But within that speed, Grange explained, one needs an extra gear when required to slip outside when a hole closes or to pull away from tacklers.

The description, Grange admitted, was inspired by what he saw out of Berwanger vs. the Hoosiers. While the Hall of Famer added the caveat that even Berwanger wasn’t all those things “[he] has a generous measure of those gifts.”

In closing the piece, Grange wrote, “Jay Berwanger can play halfback on my team.”

Berwanger did it all, basically, because he had to.

The Maroons were 3-3-2 overall and 0-3-2 in his sophomore season, finishing tied with Indiana for eighth in the Big Ten. Despite Berwanger’s exploits as a junior, and helping Chicago to a 4–0 start and wins in its first two conference games, the team dropped its last four, including 33–0 at Ohio State and 35–7 vs. the Golden Gophers to end up seventh in the standings at 2–4.

That slide began with a 26–20 loss to Purdue in which Berwanger threw two scores, caught another, and had over 200 yards of offense. But late in the game he suffered a bruised knee, and while the halfback made the trip to Columbus the following Saturday, Shaughnessy kept his star out as Chicago was outgained 266 to 130 and had half as many first downs as the Buckeyes’ 14.

As the Chicago Tribune’s French Lane wrote that day, the Maroons appeared to be waiting for “somebody like Berwanger to come along and help them out of a desperate situation. Neither Berwanger nor anybody of any ability was forthcoming, so the Maroons did the best they could.”

While Berwanger returned a week later against Minnesota, he wasn’t enough against a powerhouse that had outscored its previous two opponents 64–0. Berwanger’s double-digit tackle day, along with an interception that Barton Smith returned for a score, were among the few highlights in a game in which the Maroons managed 47 total yards.

He also handed out a souvenir to a Michigan defender who would someday be the most powerful man in the free world.

“When I tackled Jay one time, his heel hit my cheekbone and opened it up three inches,” said Gerald R. Ford, the eventual thirty-eighth president of the United States.

Berwanger would recall a later run-in, saying, “When we met again, he turned his cheek and showed me a scar on the side of his face. He told me ‘I got this trying to tackle you in the Chicago-Michigan game.’”

Berwanger wouldn’t be a consensus All-American; that honor would go to Alabama’s Dixie Howell, as Berwanger landed on the Associated Press second team, and received first-team nods via the All-American Board and Walter Camp Football Foundation.

“He is one of the finest players, one of the best defensive halfbacks I have ever seen,” Shaughnessy said that season. “He can punt with the best in the country; he is a fine passer and a horse for work.”

The coach took that final statement to heart during Berwanger’s senior year, adding signal-calling responsibilities to his plate. A reluctance to call his own number resulted in Berwanger rushing 121 times that year, compared to 184 as a sophomore when he wasn’t also serving as the quarterback.

But his average yards per carry had gone up each season, from 3.7 as a sophomore to 4.4 in his junior year and 4.8 as a senior, in totaling 577 yards. He had also improved as a passer, hitting on 26 of 68 attempts for 406 yards.

As the Maroons struggled again, going 4–4 and 2–3 in the Big Ten to tie Michigan for seventh in the standings, Berwanger’s senior season would largely be remembered for his exploits in two games.

On November 9 he ripped off an 85-yard touchdown run which the AP writer on hand described as the Chicago star “dodging and twisting in the snakiest gallop seen on Stagg Field since the famed Red Grange.”

Then, in the final game of his career, with the Maroons trailing Illinois 6–0, Berwanger took a punt at midfield in the third quarter and raced 49 yards before he was taken down from behind at the Illini 1-yard line.

On the next two plays, Berwanger called for fullback Warren Skoning, who was denied both times. Berwanger then plunged in for the touchdown himself before adding the extra point for what would be the decisive score. The Tribune headline after the win read “Berwanger 7, Illinois 6.”

Berwanger would end his career with more than a mile of yardage from scrimmage, including 1,839 yards on the ground, 50 receptions, and 22 total touchdowns.

“There wasn’t a man on the team who was jealous of Jay or who thinks he gets his just credit,” Shaughnessy would later say. “They held him in affection and were proud to play on the same team.”

A consensus All-American that season, as well as the recipient of the Silver Football he so sorely wanted, Berwanger also received a telegraph at his fraternity house from the Downtown Athletic Club telling him he’d been named the Outstanding College Football Player East of the Mississippi, beating Army’s Monk Meyer by 55 points.

“I’d won a few things that year, and I might have ignored it if it didn’t mention a plane trip to New York,” Berwanger said. “I’d never been to New York, so I went. Had a real good time, too.”

The biggest thrill, he would say many times, was his first trip on a plane as he and Shaughnessy attended a luncheon at the DAC in Berwanger’s honor. Ellmore Patterson, the 1934 Chicago captain, and College Football Hall of Fame players Pa Corbin and Hector Cowan also attended.

“The best thing about Berwanger is that he’s unspoiled by all this,” Shaughnessy said. “He’s a great kid as well as a natural athlete and good student.”

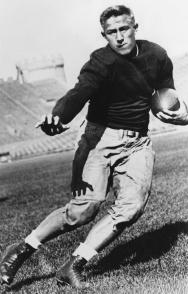

The one and only winner of the Downtown Athletic Club Award, Chicago’s Jay Berwanger beat Army’s Monk Meyer by 55 points in 1935.

(Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library)

Speculation around Berwanger’s football future was a hot topic at the ceremony, but his playing days were over.

In another first, Berwanger was the No. 1 pick in the inaugural NFL draft in 1936 and was taken by the Philadelphia Eagles. They offered him upwards of $150 a game, good money at the time given pro football’s fledgling state, but Berwanger declined.

“’I thought I’d have a better future by using my education rather than my football skills,” he would say.

His rights were traded to the Chicago Bears, and Berwanger set his demands knowing team owner-coach George Halas would never meet them. He asked for a two-year deal for $25,000 and a non-cut guarantee.

“We shook hands, said good-bye, and he and I have been good friends ever since,” Berwanger said years later. “They just couldn’t afford to pay that kind of money.”

Berwanger’s focus was on the Olympics, where he hoped to make the 1936 Berlin Games—which would be defined by Jesse Owens’s exploits under the gaze of Adolf Hitler—but Chicago president Dr. Robert Hutchins had a disdain for sports. The man who scorned schools that received more attention for athletics than academics would abolish the football program in 1939. He also refused to extend scholarships, giving Berwanger the option to graduate or focus on Berlin.

“I couldn’t try out for the Olympics and concentrate on my studies too,” Berwanger said in 1997. “If I had gone to the Olympics, I might not have ever earned my degree. Besides, I was the president of my senior class and I felt I owed it to my classmates to stick around.”

Berwanger instead graduated and took a $25-a-week job as a salesman with a Chicago rubber company. He would start Jay Berwanger Inc., a maker of plastic and sponge rubber strips for automobiles and farm machinery, after serving as an officer in the navy in World War II.

Football found a way of luring him back, as he became a coach with the Maroons months after graduating, leading the freshman team in 1936, and a year later, he added scouting duties.

He also spent fourteen years as a Big Ten official, and was at the center of controversy in the 1949 Rose Bowl between Northwestern and Cal.

During the second quarter, Wildcats fullback Art Murakowski fumbled as he lunged foward for a touchdown from one yard out. But referee Jimmy Cain signaled for a touchdown under the ruling that Murakowski’s body crossed the plane before losing the ball and Northwestern would go up 13–7 en route to a 20–14 win.

Pictures disputing the play surfaced, and the heat fell on Berwanger, who was on the goal line outside of the defensive end.

“It appears to me that Cain shifted his own responsibility onto Berwanger,” Jim Masker, the supervisor of Big Ten officials, said three days after the game. “It’s up to the official in the best position to report his observations on a touchdown play, by nod or some other sign, but the decision on whether it is a score rests solely with the referee.”

Of the dispute, Berwanger surmised, “It all depends on what part of the country you’re from as to whether I called the play right.”

But it’s a scenario that seems almost unthinkable in today’s game: an All-American running back making a call that ultimately helped his former conference win one of the most important games of the season.

Imagine Ricky Williams aiding the Big 12, Chris Weinke making a crucial call for the ACC, or Danny Wuerffel helping the SEC.

Regardless of intentions, it would be a circus.

“It doesn’t make any sense,” Butch Berwanger said. “You couldn’t have gotten away with that now.”

Jay Berwanger built his name away from the trophy, as a referee, yes, but primarily as a businessman. When he unloaded his company in the early 1990s, it was pulling in $30 million, and the Heisman was but a tool to create opportunities.

“He said that got you in the door because you could sign a picture for them or whatever, but that didn’t get the client or keep the client,” Butch said. “That just got you in the door.”

That was the humility of Berwanger, but however much humility ruled his world, his legacy was in that standing as the oldest brother of the Heisman fraternity.

****

Berwanger and his second wife, Jane, were in New York for the Heisman ceremony in 1977, when Butch Berwanger walked in the back door of the couple’s home to let their dogs out.

He turned on the little black-and-white television in the kitchen for white noise, walked into the bathroom, and when he returned, O. J. Simpson—the award’s 1968 recipient—was on the screen, giving way to Jay Berwanger.

He took the stage amid a standing ovation and his son reached for the phone, calling his siblings. None of them were watching because their father told them there was no reason to do so.

“Thank you O. J.,” he said, as he opened the envelope. “It is indeed a pleasure and an honor for me to be able to announce the 43rd Heisman winner and it goes to … Earl Campbell of the University of Texas.”

When Butch picked up Jay and Jane at the airport, he wasted little time letting him have it.

“You are in big trouble,” the son said. “When did you know that you were going to be on TV?”

“Oh, a couple days earlier,” the father replied.

During a gathering before the ceremony, Simpson was discussing the plans for the announcement itself, which would come at the end of a variety show.

The initial plan was to have a celebrity announce the winner, but Simpson had another idea.

“That’s Jay Berwanger, the first winner of the Heisman Trophy,” Simpson said to co-host and actor Elliott Gould. “He’s so admired by everybody. Have him open it.”

In the award’s first hour-long primetime event, which appeared on CBS (the network paid $200,000 for the rights), Gould and Simpson, both in tuxes, crooned “He’s a Ladies’ Man,” a cringe-worthy moment given what history would have in store for a man who stood trial for the murder of his ex-wife. Connie Stevens and Leslie Uggams performed and Reggie Jackson and Paul Hornung—the 1956 winner—handed out the first DAC Awards.

Six players—UCLA’s Jerry Robinson (linebacker), Chris Ward of Ohio State (offensive lineman), Notre Dame’s Ken MacAfee (tight end), the Fighting Irish’s Ross Browner (defensive lineman), Zac Henderson of Oklahoma (defensive back), and Campbell (running back)—were honored as the best at their position, a practice that was stopped after ’78.

After the trophy was wheeled out onto the stage on a rolling column, Simpson stated, “Now to announce the winner of this year’s Heisman, we have someone very special with us here tonight. The man who was the first recipient of the Heisman Trophy forty-three years ago … ladies and gentlemen, Mr. Jay Berwanger.”

“He never thought, for two days, of calling us,” Butch says, looking back. “[If I] was going to be on national television, [I] would tell somebody, and my dad didn’t.”

But the gesture by Simpson—beloved at the time—was indicative of the reverence the other Heisman winners had for Berwanger.

“I think we all just respected the heck out of Jay Berwanger, because he was the guy that got it started,” said 1974 and ’75 winner Archie Griffin. “Tremendous amount of respect whenever he was in the room. Everybody kind of just bowed down to him because of who he was and what he accomplished. Not just on the football field, but as a man.”

Berwanger died in 2002 in his Oak Brook, Illinois, home after a long battle with lung cancer. He was eighty-eight.

For nearly sixty years, he would rarely miss a ceremony despite running his own company and often being on the road Monday through Friday. “He was really busy with all that,” Butch said.

Yet after selling his company and enduring Jane’s death in 1998, his place as the patriarch of the Heisman—that part of him that he never shunned, but was cavalier enough with it to leave his trophy with Aunt Gussie—moved to the forefront.

“I think he really enjoyed that kind of stuff then because that’s what he had,” Butch said. “That’s what he had left.”

In his late eighties, he again donned his number 99 uniform for a photo. He was still the Genius of the Gridiron, the One-Man Gang, the Flying Dutchman. As Griffin would recount, Berwanger was known to pull aside the winners to personally welcome them in. Jay Berwanger may have been more than twenty pounds lighter than the 195 he played at, but the uniform, and his role as the Heisman godfather, all fit.

“Later in life, [so many things] kind of faded away,” Butch Berwanger said. “He really enjoyed the Heisman hype.”