CHAPTER THREE

A VOTE DRIVEN BY FOUR BIASES

A BALLOT COULDN’T GET much more simplistic, yet at the same time stand as a bigger lightning rod for criticism.

Unlike the Maxwell Award, Chuck Bednarik Award, Biletnikoff Award, Davey O’Brien Award, or any of college football’s other major prizes, which submit preseason watch lists and narrow contenders down to three finalists, the Heisman Trophy is truly an exercise in individual liberties.

The form includes three blank lines with just one disclaimer:

In order that there will be no misunderstanding regarding the eligibility of a candidate, the recipient of the award MUST be a bona fide student of an accredited college or university including the United States Academies. The recipient must be in compliance with the bylaws defining an NCAA Student-Athlete.

That’s it. Being in good standing with the NCAA is the only stated guideline placed before the hundreds of voters—in full disclosure, the author has been part of that contingent since 2008—creating a blank slate that would make it seem as if anyone from anywhere could win.

But that hasn’t always been the reality.

Unwritten rules based largely on the four predominant biases: a player’s position, class, school, and region (and for decades, the color of their skin) can exclude candidates no matter how impressive their numbers are, and set the short list of perceived favorites long before the season even starts.

Some of those limitations can and have been overcome—most notably, in recent years, the ageism of denying underclassmen—but for much of the award’s history, ceilings were constructed from biases. Neither a strictly defensive player nor any true freshman has ever won and those from outside the sport’s power conferences aren’t often viewed as legitimate contenders, with just two such recipients having been recorded thus far. It’s not meant to be a career achievement award, but there have been instances in which it has been voted on as such.

“It sure is a prestigious, highly visible award for there to be so much ambiguous criteria,” said Archie Manning in a 1997 interview. In 1970, he finished third in a race won by Jim Plunkett.

So how can we be sure the player who hoists that fabled trophy in Times Square every December truly is, as the Heisman Trust’s mission statement reads, “the outstanding college football player whose performance best exhibits the pursuit of excellence with integrity?”

We can’t.

That mere fact makes the prospect of following the annual race to New York City for the ceremony—and the responsibility of voting for it—both fascinating and maddening. Yes, at its core, we’re talking about something as inane as a college student being given a trophy, but the arguments and controversy this particular award elicits make it so captivating.

Some have argued the electorate is too large or that some of those who are a part of it don’t see enough games or are swayed by the media pushes behind players from the major conferences. They’re all valid points and, while a move to a selection committee à la the other top awards could help to educate voters and strip away some of the favoritism, it would also rob the Heisman of what makes it unlike any other award in sports.

Outstanding is truly subjective. But through the years the pursuit of defining it from season to season has shown us (though it has bent in some regards) that it can also be painstakingly exclusive.

Race isn’t the issue it once was before Syracuse’s Ernie Davis won in 1961 as the first black Heisman winner; in hindsight, it was arguably a sticking point in the 1956 vote when Paul Hornung took the trophy on a 2–8 Notre Dame team (he remains the only winner on a losing team) over the Orange’s dominant Jim Brown. Houston’s Andre Ware also broke through for black quarterbacks in ’89, leaving four distinct biases that hang over voting.

Andre Ware became the first recipient from a team that was barred from playing on TV when the Houston quarterback won in 1989.

(By University of Houston, Courtesy of Special Collections, University of Houston Libraries.)

Bias No. 1: Region

While the ballot itself remains the same as the one that Willard B. Prince developed in 1935, voting since 1977 has consisted of six regions that include 145 media votes each, giving us 870 of the 930 votes (the rest consists of former winners, as well as a single fan vote). The regions are as follows:

• Far West: Arizona, California, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, North Dakota, Nevada, Oregon, South Dakota, Utah, Washington, Wyoming

• Mid-Atlantic: Delaware, District of Columbia, Maryland, North Carolina, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Virginia, West Virginia

• Midwest: Iowa, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Minnesota, Ohio, Wisconsin

• Northeast: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New York City, New York (state), Rhode Island, Vermont

• South: Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Tennessee

• Southwest: Arkansas, Colorado, Kansas, Missouri, Nebraska, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Texas

The voting numbers that determine the winner, and those that since the practice began in 1982, are used to select the finalists who will attend the ceremony—a figure that is set by the natural break in the tallies, which is why we’ve seen as many as six players reach New York (1994 and 2013) and as few as three (ten times)—come from the overall point totals. But those aforementioned regions, and how a player performs in them in their home sector as opposed to the rest of the nation, can provide us a road map as to how someone won, or didn’t win, the trophy.

That is the foundation for one of the most oft-discussed points in the Heisman balloting: East Coast Bias.

Joey Harrington knows it all too well. Oregon ended the 2000 season with a school-record 10 wins and ranked seventh in the Associated Press Top 25, the Ducks’ highest finish ever. They achieved this success with the help of the redshirt junior quarterback, who had thrown for 2,967 yards and 22 touchdowns.

That season, Harrington helped put the Ducks back on the map, as ESPN’s GameDay descended upon Eugene, marking the first time it had ever been to the Northwest. It was just the show’s second time on the West Coast, coming in 1998 at UCLA.

“We were not the flashy Oregon team that is changing uniforms every week and little kids want to emulate,” Harrington said. “We were a bunch of nobodies that kind of made a splash and were trying to get a foothold in college football, so people weren’t exactly seeking out our games on Saturdays.”

The school made a $250,000 gamble to make sure they did, using funds from boosters for a 10-story billboard of the quarterback in Times Square that dubbed him “Joey Heisman.”

In his senior season, Harrington would throw for 2,764 yards and 27 touchdowns as well as six interceptions, including one that led to a 49–42 loss to Stanford at Autzen Stadium that ultimately kept the Ducks from playing for a national title.

It didn’t help matters that he struggled in his final regular-season game against Oregon State, completing 11 of 22 passes for 104 yards and no scores in a 17–14 win, and it didn’t aid his cause that he had a lack of national TV exposure.

Harrington would be the Pac-10 Offensive Player of the Year and earn second-team All-American honors, but it wasn’t enough to claim the Heisman.

That went to Nebraska’s Eric Crouch (770 points), with Florida’s Rex Grossman (708) and Miami’s Ken Dorsey (638) close behind, while Harrington (364) was a distant fourth in what, at the time, was the fourth-tightest race in the award’s history.

Harrington won the Far West, earning 137 of his points, but he finished no higher than fourth in any other region.

Complicating matters, just 585 of the 922 ballots were returned, with the 63.3 return rate the lowest since 53 percent (541 of 1,050) came in during the 1978 voting, when Billy Sims won. The September 11 terrorist attacks, which disrupted mail service, played its part in the low return rate, which was well below the 80 percent average at the time.

Harrington was a finalist, the first in school history, but even now he can’t help but feel like the uniform he was wearing played its part in the finish.

“I absolutely felt like if I was playing at Nebraska or Michigan or Ohio State or Texas, I definitely think people would have paid more attention,” Harrington said.

That was underscored following a 38–16 drubbing of Colorado in the Fiesta Bowl, a performance in which the Ducks quarterback threw for 350 yards and 4 touchdowns to help Oregon finish second in the AP poll.

“The thing that always struck me was, I had more people come up to me after the Fiesta Bowl and say ‘I wish I would have voted for you,’” Harrington said. “In the Fiesta Bowl we were on national television, prime time, and everybody could see it.”

“Granted, I played one of my better games that day and it coincided with Eric Crouch struggling [114 yards rushing as the Cornhuskers were held to a season-low 239 in total] against [an] incredible Miami team. But that’s what struck me more than anything is, that not that people didn’t turn in their ballots, but people didn’t look that closely or didn’t have the ability or the time and once they did see it and see the product that we put out, it was kind of an awakening.”

The following year, USC’s Carson Palmer won the Heisman, followed by Jason White (Oklahoma) and the Trojans’ Matt Leinart and Reggie Bush (though the latter was later vacated) in 2004 and ’05, giving the Far West three winners in a four-year span, as many as it had in the previous twenty-one. But it wouldn’t be until Oregon’s Marcus Mariota swept all six regions in a 2014 victory that the Far West produced its first non-USC recipient from a power conference since Stanford’s Plunkett in 1970.

“I think for a little while there, things changed in that, you saw that the next year, Carson Palmer won the Heisman … I think that a few more people were paying attention,” Harrington said.

The Far West went through an impressive stretch from 1962–70, with its first winner, Oregon State’s Terry Baker, setting off a run followed by USC’s Mike Garrett (1965), UCLA’s Gary Beban (’67), USC’s O. J. Simpson (’68), and Plunkett. But those first two victories, and the years that came before them, showed the disconnect the contenders had with some voters in other parts of the country.

In the first seventeen years after the pool of candidates expanded past the Mississippi River in 1936, no one from the Far West had finished higher than Stanford’s Frankie Albert and UCLA’s Paul Cameron, who were both third in 1941 and ’53, respectively.

Albert barely registered outside his home sector, winning there and coming in second in the Midwest, but he didn’t make another top five. It was the start of a trend, as four others—UCLA’s Donn Moomaw (’52), Cal’s Paul Larson (’54), Stanford’s John Brodie (’56), and Cal’s Joe Kapp (’58)—all won the Far West, but couldn’t mount a serious challenge elsewhere. Only Moomaw—fourth in the East and Southwest—made the top five in another region out of that group.

It made it all the more surprising then, when Baker showed a reach that went outside the Pacific Northwest in 1962, when he added a first place in the East to go with his Far West win. Baker’s outing that October against previously unbeaten West Virginia in Portland, when Baker tossed three first-half touchdowns in a 51–22 rout, certainly helped his cause.

He was third in the Southeast and fourth in the Midwest, though he didn’t even make the South’s top five.

“I was hoping, like every other football player in America does, but I certainly didn’t expect it,” Baker said days after the announcement. “I knew they’d never given it to a West Coast player before and I had some concern.”

Three years later, the Trojans’ Garrett failed to take the Midwest (second) or Southwest (fourth), despite winning the Far West, South, and East. Beban claimed those same regions in ’67, along with the Southwest, and was runner-up in the Midwest. Simpson would become the first from the region to claim all five voting sectors, a feat that Plunkett would accomplish two years later.

Those victories could have signaled that the Far West had turned the corner, and while that was true to a degree, it wound up being true for USC more than anyone.

Between Plunkett’s win and that of BYU’s Ty Detmer in 1990, the Trojans had a virtual stranglehold on the region, adding wins from Charles White (’79) and Marcus Allen (’81), along with second-places via Anthony Davis (’74), Ricky Bell (’76), and Rodney Peete (’88). In that twenty-one-year span, only three schools in the Far West region had anyone finish higher than third—Cal with Chuck Muncie in ’75, Stanford’s John Elway (’82), and BYU’s Steve Young (’83).

Maybe that had something to do with the phone call the Downtown Athletic Club received from Elway’s father, Jack, after sending a note inviting the Cardinal quarterback to the ceremony.

“Unless his son was going to win he was not going to come,” recalled then-DAC athletic director Rudy Riska. “He felt he was not there to hype the Heisman, which in all the history of it, nobody ever turned us down.”

Elway attended, finishing 695 points behind Herschel Walker, and it would be the start of an odd relationship for Stanford and the award’s voting. The Cardinal would also have a player come in second four more times, including three straight in Toby Gerhart (’09) and Andrew Luck (’10 and ’11) and, most recently, Christian McCaffrey (’15).

Gerhart had led the nation in rushing (1,736 yards at the time of voting), but lost the trophy by the smallest margin in history at 28 points. Six years later, McCaffrey broke Barry Sanders’s single-season all-purpose yardage record with 3,496 by the regular season’s end. But both lost to Alabama running backs—Mark Ingram and Derrick Henry, respectively—who played a major role in the Crimson Tide getting a shot at, and eventually claiming, national championships.

The fact that its teams often play games that don’t kick off until 10 p.m. ET always played against the Far West teams, and specifically the Pac-12. While that’s a gap that Harrington believes was narrowed for a time, advances in technology that should make for more informed voters may instead be responsible for them tuning out.

“[Contenders] were out there and [voters] were paying attention,” Harrington said, “and I think once everything because instantly accessible—you can watch just about anything you want on your phone now—people have kind of gotten lazy and fallen back into that ‘Well, I’ll just check the highlights tomorrow.’”

At first glance, Mariota’s win and McCaffrey finishing second in consecutive seasons may say otherwise, but consider that in this latest vote, McCaffrey won the Far West and finished second in the other five regions, though he had just six second-place votes more than third-place finisher Deshaun Watson of Clemson (246 to 240). It didn’t help matters that seven of Stanford’s games started after 10 p.m. ET or later.

The Far West hasn’t been alone in feeling the lack of support from other regions, specifically when it comes to battling the challenges of games played in different time zones. Five times, the Southwest—in 1939, 1941, 1945, 1954, and 1962—saw a player win its vote but fail to make another top five. But its first trophy recipient, TCU’s Davey O’Brien, came twenty-four years before Baker broke through for the West Coast, and since 1980, the Southwest has ten winners to the five recognized victors out of the Far West.

“I’m sure there is a little bit of a bias, because it’s real hard for people in the East to see all the West Coast games,” Palmer said in 2002. “Hopefully, the West Coast guys will stick behind their man.”

More than a decade after Palmer made that statement, McCaffrey is proof that there’s still more than a little truth in that sentiment. Where a player resides, though, can and has been overcome time and again in a Heisman race.

What position he plays, and more to the point, which side of the ball he plays on, makes for a different story entirely.

Bias No. 2: Position

Heading into the 1980 season, Pittsburgh’s Hugh Green was a two-time All-American and after just his sophomore season, had been named to the Panthers’ all-time team. If he were a quarterback or a running back, everyone else would have been chasing him. But Green was a defensive end, and as dominant as he was up to that point in his career, racking up 337 tackles and 36 sacks in his first three years, there was an inescapable truth.

“It’s going to go to a kid who is explosive, who can win a game,” Pitt’s defensive coordinator Foge Fazio told the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette prior to the 1980 season. “I think, being realistic, it’s a fact of life that the Heisman will go to an offensive player.”

Green would be the first defender to claim United Press International Player of the Year, and also won the Walter Camp Award, the Maxwell Award, and the Lombardi, and once again, he was a first-team All-American as the 6-foot-2, 222-pounder had 123 tackles (including 11 for loss) and 17 sacks.

“Hugh has been the best defensive player in the country the past three years in my opinion,” Pitt coach Jackie Sherrill said at the time. “Nobody can do what he can do and nobody has done what he has done at the position. He’s the best defensive player that’s been around in a long, long time. Pro scouts tell me he’s the most productive football player in America per snap.”

Despite all that, Green wouldn’t win the Heisman, though he had a theory going in. With safeties Ronnie Lott (USC) and Kenny Easley (UCLA), both like Green having been mainstays in their programs and in the national spotlight, maybe there were enough great defensive options to change voters’ mindsets.

“We had positioned ourselves defensively that if I didn’t win the Heisman someone else defensively would have won it,” Green said. “I was just one step in front of them, they had to sit and wait and they had to sit and gnaw the bone, because I was there with them in their class and doing the things that I had to do.… If you eliminate me then—BOOM!—it falls into the category of, ‘OK, if I’m not deserving, then those guys are deserving.’ One of the three.”

But the trophy, as his defensive coordinator predicted, went to an offensive player: South Carolina senior running back George Rogers. The nation’s leading rusher, Rogers won by 267 points over Green, who had to settle for second, with Georgia’s freshman running back Herschel Walker in third (that’s another contested part of this vote we’ll get into later).

Green, at least, could perhaps take solace in a 37–9 rout of Rogers and the Gamecocks in the Gator Bowl that lifted the Panthers to No. 2 in the final AP Top 25. It was just the second time the top two vote-getters in balloting had ever met in a bowl—following Archie Griffin and Anthony Davis in 1974—and stands as one of six occasions overall. While Rogers ran for 113 yards on 27 carries, he fumbled three times, losing two of them. Green was limited to 5 tackles, but South Carolina rarely ran at him and he was double-teamed for most of the night, leaving the Panthers’ other defensive end, Ricky Jackson, free to make 19 stops.

“Hands-down in that category, I wanted the competition,” Green said. “I wanted the spotlight. I wanted it to be between me and George, but again, I was mature enough to know because of offensive dictation and their respect of me, they were like ‘Well, we’re not going to run at the guy’ and they didn’t. You don’t run at me or attack me, I had to take the glory of us defensively doing what we did to shut him down and beat them like we beat them with him being the Heisman.”

The Heisman has forever been the playground of running backs and quarterbacks, with the former winning forty-two times, and the latter thirty-two. While two wide receivers—Tim Brown in 1987 and Desmond Howard in ’91—and a pair of tight ends—Larry Kelley (1936) and Leon Hart (’48)—are also a part of the fraternity, the votership has long had a narrow focus. As Ohio State’s Chris Ward said when accepting the short-lived Downtown Athletic Club’s Best Offensive Lineman Award at the 1977 Heisman ceremony, “I’d also like to accept this award on behalf of the offensive linemen in the United States, because I feel like there’s only a few keen eyes that really watch what an offensive lineman does.” Decades later, offensive linemen would still get no closer to the country’s top award than did tackle John Hicks, another Buckeye, coming in second in 1973.

Defensive linemen, cornerbacks, and then some. The list of those positions that seem to lack a chance at receiving the award seems to go on and on. A winner that doesn’t play one of those positions of power in running back or quarterback is nearly unthinkable, which has made one name stand out more than any other when it comes to truly breaking the stiff-armed mold: Charles Woodson.

The Michigan defensive back is credited as being the first defensive player to win the Heisman when he topped Tennessee’s Peyton Manning by 272 points in 1997 and won five of the six regions, with Manning taking his home sector, the South. But Woodson didn’t receive the trophy simply for his exploits at cornerback. Along with his 43 tackles, 7 interceptions, and 5 pass break-ups at the time of voting, the Wolverine had 11 receptions for 231 yards and 2 scores and returned 33 punts for 283 yards and a touchdown.

Woodson put it all on display November 22 against rival Ohio State, when he picked off a pass in the end zone, had a 37-yard reception to set up a score, and ran a punt back 78 yards for a touchdown. As he sat at the Downtown Athletic Club weeks later, Woodson said to himself, Do I really have a shot?

ESPN has taken heat over the years from Volunteers fans for the way it was believed to be waging an on-air campaign for the underdog Woodson, most notably on its College GameDay show, coming at the expense of Manning, who had thrown for 3,819 yards and 36 touchdowns in leading Tennessee to an SEC crown and over his career set 33 school records.

At the time, ESPN was showing Big Ten games and not SEC games, and after the ceremony, the network received angry telephone calls from Tennessee fans. Host Chris Fowler received a FedEx box filled with manure. Fowler responded by calling Vols fans “trailer-park trash”—he has since apologized—and further addressed the conspiracy charges years later in the oral history of ESPN, Those Guys Have All the Fun.

“People assumed Peyton Manning had the Heisman won. All I said was that this wasn’t a done deal,” he said. “I wasn’t trying to hype Charles Woodson or the show for that matter. The show was going to rate what it rated. I was just doing my job.”

Whether by design or not, Fowler and his employer weren’t alone in the perceived pushing of Woodson, as Riska was quoted as saying, “Speaking for myself, I’d like to see a player like Woodson win it. I think it would be good, not only for the Heisman Trophy, but for college football.”

He later refuted that endorsement, telling the New York Times, “I didn’t say we wanted him to win. I said if he should turn out to be the winner, it would be good for college football. It would dispel the claim that there is a wall for defensive players.

‘’That’s not saying that Peyton Manning or Ryan Leaf or Randy Moss wouldn’t be good. I didn’t mean it that way.”

After receiving the Heisman, an emotional Woodson, who received 433 first-place votes to Manning’s 281, said, “Defensive players can now go out and play their games. This has opened doors.”

Not exactly.

Woodson was, in essence, a throwback to the days before the two-platoon system, when players saw significant time on both sides of the ball. To consider him strictly a defender in regards to his Heisman Trophy win would be to undermine his impact, overestimate the voters for focusing on the other side of the ball, and demean those who couldn’t break through based solely on defense.

Green believes there was a sense of making up for bypassing him nearly two decades before.

“I just think that it was such a guilt factor in general that I didn’t get it and people felt that, ‘Oh, he should have got it. If anybody in the world [on defense] should have got it and he didn’t get it,’” Green said. “… I should have got it before him in general. All I did was just make it more serious to give it to a defensive player … but he was returning punts and doing this and doing all that. So that sort of made it easy, so in their gesture or in their half-guiltiness they felt like, ‘We should have gave it years ago [to a defender]. Now we finally ran into another guy of that breed, so let’s give it to him … and by the way, he also returns punts. He does something offensively.’”

Prior to 1965, in the one-platoon era, those who played offense always played defense, too. Hence the award’s first winner Jay Berwanger through Larry Kelley, Clinton Frank, and on and on, all saw time on both sides of the ball. Oklahoma’s Kurt Burris was second in 1954, as was Iowa’s Alex Karras in ’57, and Penn’s Chuck Bednarik finished third in ’48, but Burris was a linebacker along with center, Bednarik played those same positions, and Karras balanced defensive tackle duties by also being a right guard.

UCLA’s Moomaw won the Far West in ’52, and while he’s in the College Football Hall of Fame largely as a linebacker, like Bednarik and Burris, he was a center as well.

In the era of specialists (after the NCAA allowed teams to separate offense, defense, and special teams following the 1964 season), Nebraska’s Rich Glover was the first pure defender to truly make noise in the Heisman voting. He was third in 1972, coming in 658 points behind teammate and winner Johnny Rodgers (adding to the firsts, Rodgers was the forefather to Johnny Manziel and Jameis Winston, bringing moral character into the equation with his involvement in a service station holdup as a freshman, along with driving with a suspended license).

While Oklahoma linebacker Brian Bosworth earned the first trip to New York in 1986 after the DAC began inviting the finalists, he came in fourth that year, as did Washington defensive tackle Steve Emtman (’91). Miami defensive tackle Warren Sapp (’94), Cornhuskers defensive tackle Ndamukong Suh (’09), and LSU’s Tyrann Mathieu (’11) all made the ceremony as well, but no one could get higher than Suh’s fourth, which included claiming the Southwest.

“I started as a freshman and played every game for four years and established my credentials so I had a chance,” Green told Rivals.com in 2006. “Today for a defensive player to start as a freshman and go throughout his career, not leave early for the pros, etc. I don’t think a pure defensive player can win.”

Of that aforementioned group of finalists, only Suh was a senior (Bosworth, Emtman, Sapp, and Mathieu all would leave early for the NFL), but he was largely a backup in his redshirt freshman season. Doing what Green couldn’t would likely take a perfect storm, one that nearly came courtesy of Manti Te’o.

The linebacker had name recognition as a freshman All-American in ’09 and a second-team All-American as a sophomore and junior. He was also at one of college football’s most storied programs in Notre Dame, the launching pad for seven Heisman-winning careers, and was the poster boy for its revival under coach Brian Kelly, as the Fighting Irish earned a spot in the penultimate BCS National Championship Game.

He also had a captivating and heartbreaking narrative, with Te’o recounting to many media outlets how his seventy-two-year-old grandmother, Annette Santiago, and girlfriend Lennay Kekua—a student at Stanford—had both died on September 11, 2012. After receiving the news, he went out and racked up 12 tackles in a 20–3 upset of Michigan State.

With that backstory, 103 tackles and 7 interceptions (second most in FBS), when Heisman ballots were due, Te’o became part of a difficult choice for voters. Would they, for the first time, side with a freshman—to be clear, a redshirt—in Texas A&M’s Johnny Manziel; a player who never saw an offensive snap in Te’o; or Kansas State’s Collin Klein, the safe pick as a redshirt senior but whose campaign fell on its face in the final month?

Te’o claimed the Midwest and finished second in every other region behind 321 first-place votes, but came in 323 points behind Manziel, while Klein, the third finalist, registered just 60 firsts and was 1,135 behind the winner. Te’o didn’t leave with the trophy, but he did, however, earn 1,706 points, a record for a defender.

Though there was no solace in that for the player whom he tied for the highest finish for a defender, Hugh Green.

“I didn’t think that Manti Te’o was a player that really deserved the Heisman,” Green said. “I thought that they tried to give it to him because of where he went, which was Notre Dame, the status of them as a school. If he won the Heisman, I’d still have the same opinion that they still didn’t give the best defensive player the trophy, whereas offensively, they do.… Manti Te’o had [5] sacks. That’s not an outstanding year. The defense did some things as a team, but individually, no.”

We now know Te’o winning would have put the Heisman through an embarrassing scandal, more so than the off-the-field exploits of Johnny Football. Kekua never existed and the Notre Dame star had been “catfished,” a term stemming from the 2010 Nev Schulman documentary Catfish, about a New Yorker who tracked down a woman he met online. She turned out to be a completely different person than whom he thought he’d been involved with.

Te’o had been duped by a man, Ronaiah Tuiasosopo, who had been disguising his voice in phone calls and made the linebacker believe he was Kekua. The two had never actually met and it was later discovered that Lennay Kekua never actually existed.

On the day of the ceremony, which came two days after Te’o found out his girlfriend had been a hoax, he perpetuated the storyline, telling a group of reporters, “I don’t like cancer at all. I lost both my grandparents and my girlfriend to cancer.”

As he told Vanity Fair months later: “Put yourself in my position. I’ve just found out my girlfriend is a big prank. And I think she’s just died and people are asking me about her. And I’m just a twenty-one-year-old guy getting this question on a national stage just two days after it happens.”

Victim or not, in breaking through the glass ceiling, youth, represented by Manziel, ended up saving the Heisman from being at the center of a public relations nightmare. A funny thought given the way age has long been viewed among voters.

Bias No. 3: Age

George Rogers was a fine and rather safe pick in 1980. But like its place in the offense vs. defense debate, no Heisman race is more closely dissected than when the topic of ageism is broached.

Rogers had more rushing yards than anyone at the time of voting—1,781 off a 6.0 average per carry—and held a streak of 21 consecutive games of 100 or more yards in a period when running backs were in the midst of hoisting the Heisman in 11 consecutive years.

The South Carolina star was also a senior, and had name recognition, rushing for 1,548 yards as a junior and finishing seventh in the balloting. Rogers’s backstory didn’t hurt either, as his father—George Sr.—left home when Jr. was around six, and in 1972 was convicted of murdering a woman he was living with. As he later recounted to UPI, the two had gotten into an argument and she was shot when a gun he had in his pocket fired. Meanwhile, George Jr. and his four siblings moved around the Atlanta area, living in eight towns in all before he moved in with his great aunt.

George Sr. had been sentenced to life, but was paroled after eight years, and released just ten days before his son and the No. 14 Gamecocks took on freshman Herschel Walker and fourth-ranked Georgia on November 1. It would be the first time George Sr. had ever seen his son play.

It also marked Rogers’s first game on national television, and while the meeting of father and son in the locker room drew media attention, the day belonged to Walker and the Bulldogs.

Walker piled up 219 yards, 76 of which came on a touchdown run on the third play of the third quarter, lifting Georgia to a 13–10 win. Rogers didn’t exactly struggle–running for 168 yards–but in the spotlight for the first time, and with the storybook platform of his father watching from the stands, the South Carolina star ceded the spotlight to Walker.

What began with Larry Munson’s famous “My God, a freshman” call on the Georgia running back’s first career touchdown run in a come-from-behind 16–15 win at Tennessee, and continued with a school-record 283 yards vs. Vanderbilt in a 41–0 rout October 18 was amplified in Walker’s first test against a ranked opponent.

South Carolina provided him with a stage against a top-25 opponent and it provided him with a stage to run his season total to 1,096 yards and 10 scores through eight games, all that despite missing most of two with a sprained ankle.

“I don’t think it was a battle between George and myself,” Walker said after the win. “It was a battle between two great teams. It does not matter that I outgained George Rogers. What matters is that we won.”

In terms of the Heisman, though, it should have ultimately been all that mattered, but Walker had to settle for third behind Rogers and Green. The Gamecock won Walker’s own region (the South), while the freshman was third in the Northeast, Mid-Atlantic, and Far West and fifth in the Midwest.

“Even though Herschel outdueled him in that ballgame that we had, old George had been around for about four years,” said Georgia coach Vince Dooley. “So I think the voters’ mode of operation was to be based on not just a year, a freshman or a sophomore year, but somebody who had done it over the long haul. In light of that I was not surprised that Herschel didn’t win it, but this day and time he would probably win it.”

Walker would have to wait two more years to finally get his trophy, coming in second the following year behind 2,000-yard rusher Marcus Allen of USC. It’s that 1980 vote that sticks out, given the way he captivated a nation.

Walker’s 43 carries against the Gamecocks were a single-game Georgia record and he continued one of the finest freshman seasons in history, as he finished with 1,616 yards and 15 touchdowns, shattering the previous mark of 1,556 yards for a first-year player set by Pitt’s Tony Dorsett in 1973.

While Rogers had 278 more yards, Walker boasted four 200-yard games to Rogers’s one—two of which came on national TV—while getting just 9 carries against TCU and 11 vs. Ole Miss with the ankle injury. The phenom also powered the Bulldogs to an 11–0 record and an eventual national championship, while Rogers and South Carolina lost three games in all, including a 27–6 drubbing at the hands of Clemson (a defeat in which Rogers still had 168 yards).

The message was clear: underclassmen don’t win Heismans.

“It’s just such a stretch to believe that a freshman is going to win it, I don’t think that anybody expected that it was going to happen, but it didn’t change the feeling that he was the best player in the country,” said Georgia quarterback Buck Belue. “That’s sort of the way that the team looked at it.”

A senior won every year for the first decade of balloting, with Army’s Doc Blanchard standing as the first junior recipient in 1945, and seven seasons passed before a sophomore—Notre Dame’s Angelo Bertelli (second in ’41)—joined the top vote-getters. It was only due to freshmen being eligible because of World War II that Georgia Tech’s Frank Castleberry came in third in 1942. After 1972, the first season that freshmen were again allowed to play varsity, Walker would be the first to mount a serious challenge.

Even Dorsett in the previous record-setting season for a freshman running back made the top five in just one region—fourth in his home sector, the East—making what Walker did all the more stunning, even if he didn’t win.

“I guess I was realistic enough to understand the situation,” Dooley says in hindsight. “I was, of course, disappointed for Herschel, hoping he’d win it as a freshman, but I had a broad perspective of what was going on.”

George Rogers, by no fault of his own, became testament to the pedestal prolific juniors and seniors were placed upon, as did Oklahoma’s Jason White when the quarterback beat out Pitt sophomore wide receiver Larry Fitzgerald in 2003. Walker only tied for the best finish by a first-year player in 1980 with Castleberry (1942), a mark that would be equaled by Virginia Tech’s Michael Vick in 1999, and surpassed by Oklahoma’s Adrian Peterson in 2004 when he came in second behind USC’s Matt Leinart.

But if the last decade has been defined by any trend in voting, it’s that age has become nearly a non-issue.

The rise in the number of players leaving early for the NFL has played a part. In the first ten years after the NFL began allowing anyone who is at least three years removed from high school to declare for the draft, an average of forty-nine players left school, but in the last eleven that’s jumped to sixty-four, including a record 102 in 2014.

That’s put the onus on younger players to contribute right away, many of whom have graduated from high school and enrolled early, though it doesn’t completely account for the way Tim Tebow broke onto the national scene in 2006. While playing a part-time, but memorable, role in Florida’s 2006 championship season, the situational runner became a household name and the following year became the first sophomore winner.

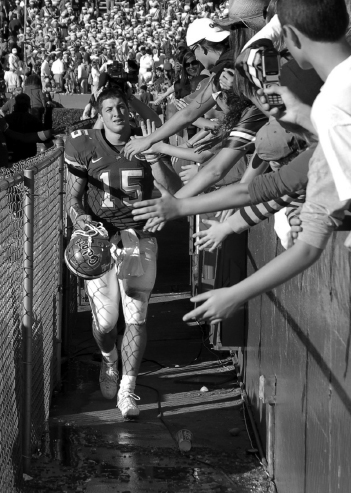

Florida’s Tim Tebow broke through for underclassmen when he became the first sophomore winner in 2007.

(By Jameskpoole, via Wikimedia Commons)

He would win five of the six regions, with the Southwest going to runner-up Darren McFadden (Arkansas), in a balloting dominated by upperclassmen, who racked up nine of the top ten spots. The first major college quarterback with 20 passing and 20 rushing touchdowns scored in a season, that 254-point margin of victory may have been even greater were he an upperclassman.

“There are a lot of great freshmen and sophomores out there,” Tebow said that night. “And I’m just glad that I get to be the first one to win this.”

The Gators quarterback started a trend, as suddenly it wasn’t just OK to crown a sophomore—with Oklahoma’s Sam Bradford and Alabama’s Mark Ingram winning the next two seasons—it was acceptable to get behind them in droves.

In 2010, redshirt junior Cam Newton won for Auburn, a victory that broke the run by second-year players. But he was followed in the voting by two redshirt sophomores in Andrew Luck (Stanford) and LaMichael James (Oregon), with another in fifth (Oklahoma State’s Justin Blackmon) and a true sophomore, Michigan’s Denard Robinson, in sixth.

Then in ’12, something happened that seemed implausible when Walker was denied in that historic 1980 campaign: Redshirt Manziel delivered for the freshman class. Then Florida State’s Jameis Winston (another redshirt) delivered another for first-years the next season.

“That barrier’s broken now,” Manziel said upon winning. “It’s starting to become more of a trend that freshmen are coming in early and that they are ready to play. And they are really just taking the world by storm.”

The run was stopped there, as Alabama junior running back Derrick Henry claimed the 2015 prize. But even that vote showed the overall power youth is holding in this current climate.

Stanford’s Christian McCaffrey came in second, with Clemson’s Deshaun Watson third, LSU’s Leonard Fournette sixth, and Florida State’s Dalvin Cook seventh, all of them sophomores. While that group helped ’15 tie the ’06 and ’10 votes for the fewest number of upperclassmen in the top 10 with six, never before had four players who were less than two years removed from high school graduation finished in the top seven.

Bias No. 4: School

At a time when nearly every college football game is available on television—either nationally or regionally—or able to be streamed on a litany of devices, the very idea of a Heisman Trophy winner that the vast majority of voters have never seen so much as a highlight of seems far-fetched.

But in 1988, the NCAA, after investigating more than 250 charges of violations in recruiting, placed Houston on three years’ probation and barred it from playing in bowl games for two. It also barred the Cougars from playing on TV for the 1989 season, creating the surreal, and somewhat ironic, scene of Andre Ware’s first appearance coming via satellite, as the Heisman winner that season.

“We’ve overcome a lot as a football team, so I’m accepting this for my teammates at the University of Houston,” Ware said during a cameo on CBS’s live telecast of the Heisman announcement. He had just led the Cougars to a 64–0 rout of Rice in which he threw for 400 yards and two scores, hence his absence from the proceedings.

“This just shows that anything is possible at the beginning of the season; who would believe I would be sitting here today accepting the Heisman Trophy?”

Ware was unseen, but the numbers largely proved too mind-boggling to ignore, even if Ware played in the kind of program that had never won before and had never been closer than when Cornell’s Ed Marinaro finished second in 1971.

Ware set twenty-six single-season NCAA records, including passing yards (4,699) and total offense (4,661) and completions (365), while throwing 46 touchdowns in leading a Cougars’ run-and-shoot offense that averaged 53.5 points per game. So dominant was Houston in rolling through the Southwest Conference that Ware sat out eight quarters with the Cougars holding massive leads.

“There’s always been the dark cloud of university probation, but I think the voters are aware now that I had absolutely nothing to do with it,” Ware told the Washington Post the day before the ceremony. “Hopefully, if they vote for someone else, it’s just because they think they are better than me.”

But Ware had his doubters and critics because of stats that were the by-product of the pass-happy Air Raid offense (and likely, because Houston was facing that TV and postseason ban), a stance that was punctuated by his pass usage in a 40–24 win over Texas Tech. That was his final outing before votes were due, and the Cougars, junior passed on 63 of the team’s 69 plays.

Nonetheless, he became the first winner on a team on probation, taking the South, Northeast, and Southwest, while Indiana running back Anthony Thompson claimed the Midwest and Far West and West Virginia’s Major Harris won the Mid-Atlantic. Thompson finished 70 points back, making it, at the time, the fourth-closest vote ever.

“We weren’t able to go to bowls this year,” Cougars coach Jack Pardee told reporters. “This was our bowl game, Andre winning for himself and for the team.”

Doc Blanchard’s win as a junior in 1946 paved the way for three more players from that class in the next five years; likewise two more sophomores immediately followed Tim Tebow, and Johnny Manziel gave way to another redshirt freshman the season after his victory.

Ware’s victory also opened the door, with Ty Detmer taking all six regions in 1990 in a season that one-upped Ware’s. The BYU junior passed for 5,188 yards and 41 scores and boasted a résumé that included a win over top-ranked Miami that September.

“You try to picture yourself in this position, but you really can’t imagine it,” Detmer told CBS. Like Ware, he appeared on the Heisman telecast via satellite with the Cougars playing in Honolulu.

Said Cougars coach LaVell Edwards, who couldn’t break through with previous quarterbacks Gifford Nielsen (sixth in 1976), Marc Wilson (third in ’79), Jim McMahon (fifth in ’80 and third in ’81), Steve Young (second in ’83), and Robbie Bosco (third in ’84 and ’85), “I think at that time it was a combination of not anybody else was really in his category and the fact that we had so many of them that were good quarterbacks, I think that helped him win the Heisman.”

But Detmer’s performances to follow that season, and the way Ware’s successor was treated in voting, helped to set the stage for a new scrutiny for players from outside the power structure.

Hours after winning the Heisman, Detmer threw four interceptions and had a season-low 48.8 completion percentage (22 of 45) in a 59–28 loss to Hawaii, and followed that by being held to just 120 yards on 11 of 23 passing and one touchdown in a 65–14 rout at the hands of Texas A&M in the Holiday Bowl. He also ceded the single-season total offense record to Houston’s new starter, David Klingler, who racked up 5,221 yards and 55 touchdowns.

Klingler was a Heisman finalist, but in a testament to how the numbers produced by the run-and-shoot were viewed, finished a distant fifth and managed just seven first-place votes to Detmer’s 316.

A year later, Detmer was third to Michigan’s Desmond Howard after a dismal start in three straight losses to Top 25 teams, drawing 445 points to the wide receiver’s 2,077, and was even third in his own voting region—the Far West—coming in behind Howard and Washington’s Steve Emtman.

Those who played on a perceived lesser stage—which included the service academies, winners of five Heismans between 1945–63—simply couldn’t break through any longer. It was a point driven home by Marinaro’s narrow loss to Auburn’s Pat Sullivan in ’71, despite the Cornell back leading the nation in rushing in back-to-back seasons; and it was there when San Diego State’s Marshall Faulk, the country’s top rusher in 1991 and ’92, was a distant second to Miami’s Gino Torretta in ’92.

Faulk’s being a sophomore may have played a part, as did the love affair with those Hurricanes teams for which Torretta was the latest poster boy, but the Aztecs’ running back was 320 points behind Torretta, earning 164 first-place votes to the quarterback’s 310.

In the years since, players from the ranks called mid-majors, and in the latest nomenclature, Group of Five, have become fixtures in the final vote tallies. Since 1994, two years—1995 and 2014—didn’t include at least one of those players in the top 10 and in that stretch, eight of them have been finalists (Alcorn State’s Steve McNair in ’94, Marshall’s Randy Moss in ’97, the Thundering Herd’s Chad Pennington in ’95, TCU’s LaDanian Tomlinson in 2000, Utah’s Alex Smith in ’04, Hawaii’s Colt Brennan in ’06, Boise State’s Kellen Moore in ’10, and Northern Illinois’s Jordan Lynch in ’13), but none have been closer than McNair’s third place.

Being a quarterback or a running back can pave the way, as can being a junior or a senior or playing in a region with start times that can get a player eyeballs. But the team, and one’s spot in the college football universe’s pecking order, has become a major force in voting for the past twenty-five years, one that has only been magnified as everything else in the game orbited around the BCS, and now the College Football Playoff. A trip to New York seems to be the new ceiling for those who don’t play in the ACC, Big Ten, Big 12, Pac-12, SEC, or don’t suit up for Notre Dame.

Biases, in all their forms, make the process of defining outstanding, as votes both past and present assure us, full of limitations.