CHAPTER SEVEN

O. J., BUSH, AND TARNISHED BRONZE

“FAME IS A vapor, popularity is an accident, and money takes wings,” O. J. Simpson told Sports Illustrated in November 1979, a quote that he was unsure of the origins of, but had heard it one night on TV in Buffalo, the words bringing him out of his chair. “The only thing that endures is character.”

The downfall of the former Southern California running back, beginning with him as the centerpiece of a shocking murder trial, stripped all that away from the 1968 Heisman Trophy recipient.

Quickly, fame turned into infamy.

On July 28, 1994, a month after the Bronco chase on Los Angeles’s 405 Freeway, USC custodians noticed that the copy of Simpson’s Heisman that was given to the school, along with his jersey from the ’68 season, were missing from the lobby of Heritage Hall.

School spokesman Rob Asghar said in a press release that “the removal of the trophy and jersey is believed to be the first incident of vandalism or theft against memorabilia located in the building.” But the student newspaper, the Daily Trojan reported in the spring of 1994 that women’s basketball coach, Cheryl Miller, had stopped the theft of Charles White’s jersey. White had won the Heisman in 1978.

This was different, though. People had flocked to the heart of the redbrick campus in the aftermath of Simpson’s arrest on a double murder charge for killing his ex-wife, Nicole Brown Simpson, and friend Ronald Goldman. When Simpson was leading police on that low-speed chase, the Los Angeles Police Department came to the football offices requesting that as a precautionary measure Simpson’s items be removed, for fear that they would be stolen.

As the only staff member in the office, kicking coach Jeff Kearin obliged, taking the trophy and jersey out of the case and hiding them.

“It has nothing to do with shame,” USC assistant Jeff Kearin told the Associated Press of the items’ removal. “He’s still a great Trojan and a great football player, a huge part of the heritage of USC football.”

Three days later the items were back on display … until workers discovered the empty Plexiglas cases. The items had previously been sitting on top of podiums, which had since been dismantled and the items gone. Los Angeles police investigators—who believed two thieves were responsible—found that the screws that were holding the display together had been removed.

“They just lifted up the Plexiglass box that covered the trophy and took it, along with the jersey,” Lt. James Kenady of USC security said to the Los Angeles Times.

USC sports information director Tim Tessalone told ESPN.com in 2009, “We waited for a while, hoping it might turn up. It never did. It’s probably in the bottom of Santa Monica Bay. You can’t fence a Heisman.”

Another piece of Simpson’s football legacy showed up on the side of Cleveland’s Interstate 77 near the East 30th Street a year later. An Ohio Department of Transportation litter crew came across a nearly 40-pound bust that had been stolen from nearby Canton’s Pro Football Hall of Fame in July 1995. The suspect, a white male estimated in his thirties, had taken it as crowds died down at the end of Hall of Fame Week.

That bust remains in the HOF, and in the wake of the trophy being stolen, the Trust would supply USC with another copy. USC continues to display it, along with those won by Mike Garrett (1965), Charles White (1979), Marcus Allen (1981), Carson Palmer (2002), and Matt Leinart (2004)—but these days the school has increased security measures, as all of the Heisman cases are alarmed.

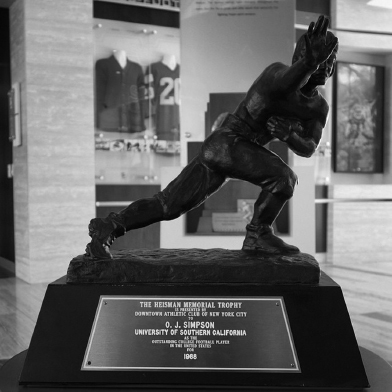

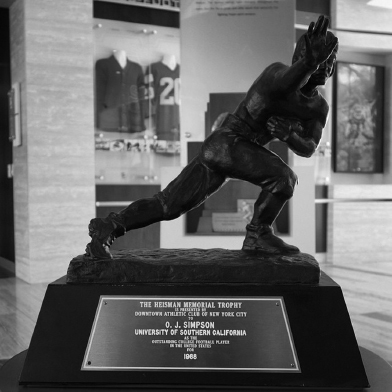

The copy of O.J. Simpson’s Heisman, which replaced the one that was stolen from USC’s Heritage Hall in 1994.

(Robert Raines/Flickr)

Simpson’s trial gripped a nation and the verdict—an acquittal—divided it. The civil suit brought by Goldman’s parents cost him his Heisman Trophy, as the former running back was forced to sell it to raise funds to pay the $33.5 million judgment. The award fetched $255,500 in auction in 1999, purchased by Tom Kriessman, the owner of a small steel company, who said he only bid to impress his then-girlfriend.

“You just get caught up in things sometimes,” Kriessman told the Washington Post in 2013. “It sort of snowballed and it happened.” He keeps the Heisman in a safety deposit box in Philadelphia, rarely visiting it.

Simpson is serving a nine- to thirty-three-year sentence in a Nevada prison for armed robbery and kidnapping stemming from a 2007 incident in the Las Vegas hotel room of collectors in which he demanded the return of memorabilia the ex-running back claimed were stolen.

His character—the only thing that endures—was tarnished long ago, but Simpson remains a recognized member of the Heisman fraternity, relaying his ballot from prison. In fact, Simpson’s not alone in that arena, as 1959 winner Billy Cannon served two and a half years for his part in the seventh largest counterfeiting scheme in US history, but what he accomplished on the field remains untouchable.

During the court-ordered auction in 1999 to begin satisfying the wrongful death judgment against him, a conservative Christian group spent upward of $16,000 on Simpson’s Hall of Fame plaque and signed USC and Buffalo Bills jerseys. The plaque—bought for $10,000—was dismantled and set on fire, the jerseys left smoldering.

“We are destroying O. J. Simpson’s property in front of the L.A. courthouse because the criminal justice system is destroying justice before our very eyes,” a Denver radio host, Bob Enyart, told the Los Angeles Times.

But as an onlooker screamed out: “You can’t take it away from him! He still earned it!”

Therein lies the harsh reality of dividing O. J. Simpson, the man at the center of one of this country’s most famous court cases, and the man known as “Juice.” As far as the Heisman’s keepers are concerned, any legal troubles have and will continue to have no impact on the player that the Trojans running back had been during his winning year of 1968.

“The rules are that the person has to be an eligible college athlete to win the trophy,” said Heisman Trust president William J. Dockery. “What happens after they win the trophy is obviously concerning to the Trust, and would prefer that there are no bumps in the road, but we don’t feel that we have any ability, once the trophy is earned by somebody legitimately, [to take it away].

“A certain segment of society makes mistakes, and probably the percentage of Heisman winners who have is probably less than the percentage of people in society who have gotten involved in things like O. J. got involved in.”

When he accepted the trophy that season, Simpson detailed his conflicting feelings on being a football star, saying, “I’m here because I’m O. J. Simpson, football star, not because I’m just O. J. Simpson. I couldn’t afford to be here any other way.” Then he added something that would seem even more impossible decades later. “Sometimes,” he said, “I just wish I could be a normal person again, to play football without having to share my life with the public.”

A year after finishing second to rival UCLA’s Gary Beban, he received 2,853 points—which, it should be noted, came when there were 1,200 registered voters, a figure that was later pared down—a total that is the most of anyone, and he still holds the record with 855 first-place votes. Even Ohio State’s Troy Smith, who sat atop 91.6 percent of ballots, the most in history, didn’t earn as many firsts (801) as Simpson did in that bloated voting environment.

Simpson remains a measuring stick for every vote, so while he may no longer have his Heisman, the Heisman—in every way that truly matters—still has him.

What it doesn’t have is Reggie Bush.

In September 2010, the giant No. 5 jersey—Bush’s number—that sat just to the right of Matt Leinart’s in the peristyle end of the L.A. Memorial Coliseum was removed. These days, hashtags and asterisks have been added to dozens of mentions of his exploits in the Trojans’ media guide, which is now littered with “Bush’s records at USC have been vacated due to NCAA penalty,” “Bush’s participation later vacated due to NCAA penalty,” and under the Heisman Salute portion of the 200-plus-page tomb, “USC TB Reggie Bush won 2005 Heisman Trophy, but award was later vacated due to NCAA penalty.”

The exorcism of Bush from Trojans football lore was swift. Just three months removed from the NCAA handing down sanctions that were its toughest since Southern Methodist’s football team was given the “death penalty” in 1986—its entire 1987 season was canceled and while it could have played an abbreviated schedule in ’87, chose not to—USC followed the governing body’s order to disassociate itself from Bush and former basketball player O. J. Mayo, both of whom were found to have received improper benefits.

The NCAA infractions committee’s sixty-seven-page report stated that from October 2004 to November 2005, Bush, his mother Denise, and his stepfather LaMar Griffin joined sports marketers Lloyd Lake and Michael Michaels to form the agency New Era Sports and Entertainment. The company then provided Bush and members of his family a rent-free home in San Diego, airfare, and a vehicle. They also supplied Bush with the suit in which he accepted his Heisman Trophy.

Lake and Michaels would later sue Bush in attempts to recoup nearly $300,000 they said they lavished on the family in hopes of signing him as their first client.

“The general campus environment surrounding the violations troubled the committee,” the NCAA infractions report said. “At least at the time of the football violations, there was relatively little effective monitoring of, among others, football locker rooms and sidelines, and there existed a general postgame locker room environment that made compliance efforts difficult.”

As a preemptive move, USC self-imposed penalties for basketball, banning itself from postseason play in 2009 and ’10, vacating 21 wins from the 2007–08 season that Mayo participated in, and it returned money it received through the Pac-10 for the 2008 NCAA tournament. It also lost two scholarships, was docked twenty recruiting days, and one coach was unable to recruit off-campus for the following summer. Plus, coach Tim Floyd had resigned the previous June after being accused of giving $1,000 in cash to middleman Rodney Guillory to help land Mayo.

The NCAA didn’t levy any further sanctions against that program, and the same with the women’s tennis team, which was cited for unauthorized phone calls made by a former player. But football was a different story entirely.

The Trojans lost thirty scholarships over three years, had to vacate 14 wins from December 2004 through the ’05 season, which included one over Oklahoma in the 2004 BCS Championship Game and Bush’s entire Heisman-winning season that ended with another national title game against Texas in the Rose Bowl.

“Elite athletes in high-profile sports with obvious great future earnings potential may see themselves as something apart from other student-athletes and the general student population,” the NCAA report said. “Institutions need to assure that their treatment on campus does not feed into such a perception.”

The NCAA also prohibited non-school personnel, outside of media and a select group of others, from practice camps and from the sidelines during games. Gone were the days of stars roaming the Coliseum. The NCAA had discussed a TV ban, but relented, saying their sanctions “adequately respond to the nature of violations and the level of institutional responsibility.”

Athletic director Mike Garrett, the school’s first Heisman winner, took a defiant stance when he spoke to a group of boosters at the USC Coaches’ Tour at the in Burlingame, California, saying, “As I read the decision by the NCAA, all I could get out of all of this was … I read between the lines, and there was nothing but a lot of envy, and they wish they all were Trojans.”

In a video statement, former Trojans coach Pete Carroll, who had left for the NFL’s Seattle Seahawks, said he was “absolutely shocked and disappointed in the findings of the NCAA.”

USC appealed the penalties and findings in 2011, asking the Infractions Appeals Committee to reduce the harshest penalties in half, arguing the bowl ban and loss of scholarships were excessive. The school pointed to NCAA decisions that were handed down after the sanctions against the Trojans, including those involving Auburn (Cam Newton was allowed to continue playing in 2010 despite the governing body ruling Newton’s father had asked Mississippi State for cash during his recruitment) and Ohio State (in the scandal that cost Jim Tressel his job, five players were banned for five games in 2011 after the NCAA ruled they sold rings, jerseys, and other items and received improper benefits from a tattoo parlor).

The NCAA denied the appeal, upholding the infraction committee’s findings.

“We respectfully, but vehemently, disagree with the findings of the NCAA’s Infractions Appeals Committee,” the university said in a statement. “Our position was that the Committee on Infractions abused its discretion and imposed penalties last June that were excessive and inconsistent with established case precedent.”

Among those initial sanctions, running backs coach Todd McNair was also hit with a one-year “show-cause penalty” that kept him from recruiting. The NCAA slammed McNair for pleading ignorance of Bush’s dealings. McNair, whose contract with USC wasn’t renewed in 2010, filed a defamation of character suit against the NCAA in ’11.

The NCAA Committee of Infractions process was at the center of the argument, which referenced emails sent between committee liaison Shep Cooper to Rondy Uphoff, a Missouri law professor who was on the 10-person committee, but was a non-voting member.

Cooper wrote on February 22, 2010, “[McNair’s] a lying, morally bankrupt criminal, in my view, and a hypocrite of the highest order.” In another email, Uphoff wrote to Cooper, “I fear that the committee is going to be too lenient on USC on the football violations.”

The NCAA asked to have the case thrown out in 2012, but a Los Angeles Superior Court denied the request. A judge wrote that those emails “tend to show ill will or hatred.”

That ruling was also appealed and in December 2015, a three-judge panel reviewed the evidence and gave the most damning take on the NCAA’s investigation.

“This evidence clearly indicates that the ensuing [NCAA infractions committee] report was worded in disregard of the truth to enable the [NCAA committee] to arrive at a predetermined conclusion that USC employee McNair was aware of the NCAA violations,” said the ruling from California’s Second District Court of Appeal. “To summarize, McNair established a probability that he could show actual malice by clear and convincing evidence based on the [committee’s] doubts about McNair’s knowledge, along with its reckless disregard for the truth about his knowledge, and by allowing itself to be influenced by nonmembers to reach a needed conclusion.”

Five years after filing suit, McNair can take his case to trial. While the judges’ ruling will likely add more fire to the arguments over USC’s treatment and the fairness of the sanctions, it may never fix what it’s done to Reggie Bush and a trophy he called “a dream come true.”

****

Vince Young doesn’t want it.

In September 2010—three months after the NCAA levied its sanctions—Bush announced that he was forfeiting the ’05 award amid pressure after that season was vacated. In a statement released by the New Orleans Saints, for whom he was playing at the time, Bush said, “I know that the Heisman is not mine alone. Far from it. I know that my victory was made possible by the discipline and hard work of my teammates, the steady guidance of my coaches, the inspiration of the fans, and the unconditional love of my family and friends. And I know that any young man fortunate enough to win the Heisman enters into a family of sorts. Each individual carries the legacy of the award and each one is entrusted with its good name.

“It is for these reasons that I have made the difficult decision to forfeit my title as Heisman winner of 2005.”

A day later, the Heisman Trust took the unprecedented step of vacating the award altogether. The season and that vote—which included a record 91.8 percent of all possible points—no longer existed.

“The Trustees of the Trust have been monitoring the NCAA investigation of Reggie Bush and USC since first announced,” the Trust said in a statement. “We determined that no action was necessary by the Trust unless and until the NCAA acted and issued its report. Since the issuance of the NCAA decision vacating USC’s 2005 season and declaring Reggie Bush an ineligible athlete, the Trustees have met, discussed and reviewed all information underlying this decision in an effort to exercise the due diligence and due process required of any decision regarding the awarding of the 2005 Heisman Trophy.

“As a result of Reggie Bush’s decision to forfeit his title as Heisman winner of 2005, the Trustees have determined that there will be no Heisman Trophy winner for the year 2005.”

But minutes before the Heisman Trust made its announcement, Texas coach Mack Brown was urging Young, his former quarterback, to say he wanted the trophy. “I told him I’d like for him to stand up and say you want it because it’s important to bring it back here,” Brown told the Dallas Morning News. “So more than anything, he’s trying to help the team, he’s listening to me and is trying to help the athletic department rather than himself.”

But Young, who lost that vote by 933 points, took an entirely different stance when asked whether he could even accept a Heisman he didn’t truly win.

“I would not want to have it, and don’t want the trophy,” Young told reporters. “Like I said, 2005 Reggie Bush is the Heisman Trophy winner. Why would I want it?”

That sentiment was echoed by Young’s mother, Felicia, who also came to Bush’s defense when she told the Morning News, “We’re not interested in having no honor and no glory out of somebody else and trying to tear them down. They did not give Vincent the Heisman when he was there, even though I know that my son, he was the one that should have had the Heisman, but God didn’t see it that way. He gave it to Reggie Bush.”

But then there was the matter of actually giving it back.

Months before he officially took over as USC president, Max Nikias announced a number of moves in a statement, among them that Pat Haden, a former Trojans quarterback under coach John McKay, would be taking over as athletic director. He ordered the removal of any image of Bush and Mayo from any murals or displays—before students arrived back on campus in August.

He closed with this: “The university also will return Mr. Bush’s 2005 Heisman Trophy to the Heisman Trophy Trust in August.”

Bush said he would follow suit in September of that year, telling the Times-Picayune after a Saints practice, “This is definitely not an admission of guilt. For me, it’s me showing my respect to the Heisman Trophy itself and to the people who have come before me and the people who’ll come after me.

“I just felt like it was the best thing to do at this time. I felt like it was the most respectable thing to do, because obviously I do respect the Heisman. I do respect everything that it stands for, and respect all the people who came before me and who will come after me … just to silence all of the talk around it, all the negativity around it. I felt like this would be the best decision right now.”

But nearly two years later, the Heisman Trust had yet to receive Bush’s trophy. He had donated his copy to the San Diego Hall of Champions, which had it in storage while a number of their exhibits were being remodeled. In July 2011, the museum made the following announcement: “The San Diego Hall of Champions today returned Reggie Bush’s Heisman Trophy to the Bush family. In doing so, the organization feels it is best to direct any further questions to the Bush family or the Heisman Trust.”

In a 2012 appearance on The Dan Patrick Show, Bush said that he had personally mailed the trophy to the Trust. He is the Heisman Winner That Never Was, and while his accomplishments were wiped from history, that won’t truly disappear.

“Everyone still knows Reggie Bush was the best player that year. Look at the runs. He was clearly the best player,” Johnny Rodgers, the 1972 Heisman winner from Nebraska, told the AP in 2010.

“O. J. Simpson got accused of a murder and they didn’t take his back. That was a far greater allegation, and they didn’t find O. J. guilty on that.”

Bush wasn’t the first Heisman recipient to turn over his award, although Frank Sinkwich’s move had nothing to with a scandal. Georgia’s first winner, in 1942, the halfback had been keeping it in an empty bedroom in the apartment of his Bulldogs teammate, George Guisler. At the urging of Loran Smith, who would spend decades working in the school’s athletic department, arrangements were made and Sinkwich gave Georgia the Heisman during halftime of a game in 1970. Because of this act, the Downtown Athletic Club would begin awarding two trophies: one for the school and one for the player.

Bush’s award now sits in a storage unit in the New York area, crammed among the memorabilia the Trust could no longer house after the Downtown Athletic Club closed its doors.

“Nobody was happy about the Reggie Bush situation,” Dockery said. “I think Reggie has gone on, he’s had a nice career, he’s done charitable work. He [just] made some bad decisions.”

****

In 1995, USC believed it had found its missing trophy. They received a call from Redondo Beach attorney Tom Loversky. As he would recount to the school, a man had come by his office and handed over what he said was O. J. Simpson’s Heisman.

But as Lt. James Kenady of USC security told the Los Angeles Times, “It doesn’t look quite right to me. I don’t know what we’ve got.”

Loversky wouldn’t disclose the name of the man, nor would he say how that man had come in possession of the faux award. It was not Simpson’s award, though, and the trail would go cold. That is, until Lewis Starks Jr. contacted USC to authenticate an award as the one Simpson won in 1968.

Starks didn’t steal the Heisman, of that he was adamant, telling TMZ in September 2015 that he acquired it and a plaque of Simpson’s in 1996 for a burgundy Honda Accord and $500 in cash. The man from whom he bought it—who was believed to have received it from a person involved in the theft—had the trophy buried in his backyard. Starks was in prison at the time of the award’s theft, having been convicted of a separate burglary.

Shortly after he purchased the Heisman, Starks became homeless, yet he kept the trophy with him and had taken the nameplate off the award’s wooden base so it could not be identified by police. He lived on street corners and storage lockers, until he called Heisman officials and later brought the items to the USC campus in 2015, asking them to authenticate the trophy.

“It’s an interesting story,” Los Angeles Police detective Donald Hrycyk told The Press Enterprise in 2015. “It illustrates taking something famous, and what are you going to do with that?”

Prosecutors would say Starks had plans of selling the Heisman in an online auction for $70,000, though as Hrycyk would later testify, “He wanted to see if he could get a finder’s fee or reward.”

The school notified the LAPD’s Art Theft Detail and on December 16, 2014, detectives obtained a search warrant for MetroPCS records of a person they believed was connected to the missing Heisman, pointing them to Starks. After a nearly yearlong investigation, Starks was charged on September 2, 2015 in case BA439447 with one count of receiving stolen property. He was accused of, per a Los Angeles District Attorney’s Office release, “being in possession of the university’s copy of the trophy and the plaque, knowing that it had been stolen.”

California statutes, outside of a few exceptions, limited the period in which someone could be charged with theft to three to four years. All Starks, fifty-seven, could be charged with was a felony count of receiving stolen property.

During a January 2016 hearing, an L.A. Superior Court judge denied a motion to dismiss the case or reduce it to a misdemeanor, and in July of that year, Starks—who had pleaded not guilty to a felony count in September 2015—changed his plea on the charge of receiving stolen property to no contest June 30. That same day he was sentenced to three years’ formal probation.

As for the trophy and plaque, they were returned to USC. The school has not made it clear what it plans to do with the additional trophy, but its first task was having it reassembled. The award came back in three pieces—the same condition authorities discovered it in back in 2014—and an ironic state given the way Simpson, by his own doing, has seen his public image ripped apart. Regardless of the verdict in that double murder trial, he sullied the trophy in a far more detrimental way than anything that led to Bush’s deletion from the award’s history.

Dockery recalls the weight of that decision that faced the Heisman Trust. Eligibility is paramount, and the Trojans running back was deemed ineligible, giving the Trust little choice in the matter.

“The rules and regulations are that the winner has to be an eligible college athlete and he was declared ineligible, which made him ineligible for the trophy,” Dockery said. “The trophy stands for achievement, for diligence, for hard work, for the pursuit of excellence with integrity, and the integrity is an important part [of] what we believe the Heisman stands for.

“We think it’s a symbol or an icon to the youth of America—or at least the football-playing youth of America—something to strive for, something to attain, but it has to be attained correctly, by complying to the rules, and with integrity.”

But then there’s this: Simpson’s trophy continues to be displayed in Heritage Hall, while Bush’s sits in a storage unit—one standing firmly as an embarrassment, the other forced from history.

What, really, is worse for USC and for the Heisman?