CHAPTER EIGHT

THE MAKING OF A MODERN CAMPAIGN

JOHN HARRINGTON AND his son were walking up a New York City street when it first appeared in the distance, growing larger and larger as they approached, an oversized, familiar face staring back at them.

“I think the best way to describe how we both felt was just overwhelmed,” the son said fifteen years later. “I remember neither one of us said very much as we got up to it.”

There, across from Madison Square Garden, plastered on the side of a building, was an 80 x 100-foot billboard of Oregon quarterback Joey Harrington, or JOEY HEISMAN, as the $250,000 massive poster proclaimed.

Really, who could blame the Harringtons for being speechless in that moment as they took it in for the first time?

Father and son simply sat and looked at it, finding a spot on the wall outside of the venerable arena, neither saying very much as they continued to look up at the billboard. They sat in silence until a man in a New York University sweatshirt walked by, coming from the Harringtons’ right to their left.

The local, upon seeing the duo staring at the giant poster, looked up as well as he passed and then turned his attention to the Ducks passer. He shot a look at the billboard and then again one toward the quarterback before turning a corner.

Then he stopped.

The man again peered at the giant poster and back at Harrington, then in a thick New York accent asked, “Hey, is that you?”

“Yeah, it is,” Harrington replied.

“Huh,” the man said. “Cool.”

Then he walked away, leaving the Harringtons alone to again bask in the glow of the billboard. “Well, I guess that’s a good way to put it,” Joey said. “Cool.”

They were taking in the idea of Ken O’Neil, a Portland businessman and Oregon alum, who was also a close friend of Nike founder and Ducks mega-booster Phil Knight. O’Neil had been in New York for the US Open tennis tournament and, while walking around the city and seeing a number of billboards, a thought struck him.

O’Neil called Oregon assistant athletic director Jim Bartko and the wheels were in motion. The school used Nike’s ad agency, Wieden-Kennedy, to buy the space for the poster.

“We never get recognized by the East Coast,” O’Neil told the Register Guard in 2001. “And to me, this is the East Coast, right here in New York. And we thought a lot of people would ask, ‘What are these guys doing? Who is this guy? Where’s Ore-gone?’ It was kind of the ultimate tickler ad.”

The price tag—which was met by eight anonymous boosters who teamed up to buy the banner—may have seemed exorbitant, but they also considered taking out a full-page ad in an issue of Sports Illustrated (also tossed around by the Ducks athletic department were footballs with Harrington’s handprint and bobbleheads). That, on its own, would have cost about $250,000, so instead of a one-off splash, the Harrington billboard, which went up in June, was scheduled to run for three months, though it would be up for five, at no additional cost. Still, it came with its critics.

“Though the billboard seems unlikely to win Harrington the Heisman, it does serve a useful purpose,” a New York Times editorial piece said. “It dramatizes the skewed priorities of high-powered college athletic programs. Athletic directors, awash in television revenues from football and basketball programs and generous alumni donations, are increasingly running their departments as independent fiefs. It is hard to believe there was no more constructive way for the University of Oregon to spend $250,000.”

Harrington heard those concerns in Eugene, Oregon, and years later, still believes they were off base.

“There’s always going to be people who said we could have used that money somewhere else,” Harrington said. “Well, the reality is it wasn’t like it was university funds. It was money that was donated by alums to push [football].”

That it did, helping to turn the Oregon Ducks into a national brand—and it did its part in making Harrington one of the biggest names in college football in 2001.

Of course, his play didn’t hurt, either. Harrington didn’t crack the top 10 in the Heisman voting in 2000 when he threw for 2,976 yards and 22 scores for the 9–2 Ducks. But coupled with a 10–1 regular season and 2,764 yards and 27 touchdowns through the air, he ended up in New York for the ceremony along with Eric Crouch of Nebraska, Miami’s Ken Dorsey, and Florida’s Rex Grossman.

“Had we played poorly, it would have been a giant flop,” Harrington said. “But instead, we kind of woke the country up to what was going on and they started paying attention.”

It didn’t deliver the Heisman, though, as Crouch won, followed by Grossman, Dorsey, and Harrington. But that fourth place amounted to the highest finish in Ducks history.

“I wholeheartedly believe that I would not have been sitting in that room as a Heisman Trophy finalist without that billboard,” Harrington said.

But that wasn’t the end for the giant poster. In June 2003, less than a year after he had been drafted by the Detroit Lions with the No. 3 pick, Harrington returned to his alma mater and unveiled the billboard’s next life. It would be cut into little bits and sold—the proceeds going to establish a scholarship fund for Oregon’s Lundquist College of Business, the program through which Harrington earned his degree in business administration—each chunk of the banner mounted next to a reproduction of the “JOEY HEISMAN” banner.

“It was nice, at least, to be able to take some of that criticism and redirect it,” Harrington said. “It was a nice way to kind of round the whole story out.”

The billboard served its purpose, both for Harrington and the Ducks. Though in the realm of trophy marketing, the lasting impact of brash and aggressive tactics may not be its success, but its standing as the zenith of excess.

By comparison, what Budd Thalman—the father of the Heisman campaign—did in 1963 seems quaint in hindsight, but at the time, it was groundbreaking. He sent out 1,000 four-page mailers—the size of index cards—that said “Meet Roger Staubach.”

“I mailed a preseason pamphlet to a lot a people,” Thalman told ESPN.com in 2000. “He was on the cover and then it had his bio, some selected statistics and quotes from people around the country. People had gathered information like that before, but I don’t think anyone had ever printed it.”

The former Naval Academy sports information director was given clear orders: mount a campaign to put the nation on notice about Staubach, the Midshipmen’s quarterback. So he sent out the cards, and once a week he’d ride a train from Annapolis to New York, statistics in hand, to attend the weekly college football writers’ meetings and discuss the quarterback.

It resulted in Staubach appearing on the cover of TIME magazine in October, and LIFE was slated to follow suit the following month, with a crew shadowing the quarterback for a week for their lead story.

“Is there anything that could derail it?” Thalman asked a LIFE magazine spokesperson.

“Only some kind of catastrophe,” they replied.

One week before the issue was to hit newsstands, the nation was faced with a catastrophe, as John F. Kennedy was assassinated. LIFE instead ran a thirty-six-page special issue, and Staubach’s cover was scrapped.

The country had more important concerns at the time, but the voters had, indeed, met Roger Staubach. He ran away with the Heisman, winning by 1,356 points over Georgia Tech quarterback Billy Lothridge.

“Someone called me ‘the Father of Heisman Hype,’ and I’ve been trying to live it down ever since,” Thalman told ESPN.com.

To be fair, a year before Staubach’s win, Oregon State SID John Eggers would copy quarterback Terry Baker’s statistics from every game on a mimeograph machine and send them out to voters. With postage at five cents, it’s doubtful that Eggers spent more than $100.

“For the eastern writers who never had seen Oregon State—and games were not on TV then like they are now—they would have known very little about what was going out here, but for what information he spoon-fed to them,” Baker told Oregon State in a 2014 Q&A. “So that was very creative at that time.”

Schools would soon up the ante. In 1967, UCLA sent out 1,000 color brochures calling quarterback Gary Beban “The Great One,” as he went on to win, and Notre Dame went so far as changing the pronunciation of a candidate’s name.

As the story goes, someone said, “There’s Joe Theismann” (saying it as Theesman), and Notre Dame’s SID, Roger Valdiserri, replied, “No, it’s Theismann, as in Heisman.”

South Bend Tribune sports editor Joe Doyle would credit Valdiserri in his column, then a year later, Sports Illustrated used “rhymes with Heisman” in its December 9, 1968 issue.

In his 1987 autobiography Theismann, the QB recalled Valdiserri calling him into his office.

“There’s the Heisman Trophy, Joe, and I think we should pronounce your name as Thighsman,” the SID told him.

Theismann called his father, who would tell him that despite their saying “Theesman,” his grandmother insisted it was “Thighsman.” The family had registered in American schools as Theismann after they had emigrated from Austria, because it was the easiest way people could read the name.

“Well, my grandmother pronounces it that way,” Theismann would tell him. “What the heck, let’s do it.”

The Heisman may have been in his name, but it wasn’t in his future, as Stanford’s Jim Plunkett beat him out during his senior season of 1970. Theismann earned 242 first-place votes to Plunkett’s 510 first-place votes, coming in 819 points behind.

No Heisman campaign would be quite that permanent—family history not withstanding—but by the 1980s, the outlandish and gimmicky was becoming more commonplace.

In 1980, Pitt mailed out life-sized posters of 6-foot-2, 225-pound defensive end Hugh Green, and four years later, Clemson would repeat the process in promoting 6-foot-3, 335-pound nose guard William “The Refrigerator” Perry (the Tigers gave a nod to that effort in 2009 with another poster, this one for running back C. J. Spiller).

BYU sprinkled rolled oats into envelopes along with information about center Bart Oates in ’81, and that same year, Richmond pushed running back Barry Redden, including T-shirts, hats, and calendars promoting him for the award to go along with its weekly reports. Georgia campaigned for Herschel Walker in ’82 by mailing out weekly updates on its running back in mailers that included “Herschel for Heisman” artwork.

West Virginia got creative in ’83 for Jeff Hostetler, celebrating the quarterback with 45-rpm records of a ballad titled “Ole Hoss,” which was put to the tune of the theme from the television show Bonanza and sung by country artists Mark Newhouse and Brad Reeves. “It’s really bad,” Hostetler said in 1983. “It sure isn’t a top 40 hit.”

Temple followed suit by creating a sixteen-page comic book about running back Paul Palmer in 1986, but the Owls’ push also included a celebrity cameo. When golf legend Arnold Palmer—a Latrobe, Pennsylvania, native—was playing in a tournament near campus, university officials took Paul to the course for a photo of the two. They mailed it out to voters with the caption: “Pennsylvania Has Two Palmers.”

Winners Andre Ware of Houston (1989) and BYU’s Ty Detmer (’90), had their own campaigns, with Houston making up for a lack of television exposure due to NCAA sanctions by sending out a weekly flier to potential voters for “Air” Ware that looked like an airline timetable; BYU mailed out cardboard ties for Detmer that opened to reveal the passer’s stats.

Washington State greeted voters with an envelope containing a single leaf for quarterback Ryan Leaf in 1997, and then five years later the school delivered a truly tongue-in-cheek promotion for another quarterback, Jason Gesser.

In retaliation of Oregon’s six-figure banner for Harrington, the Cougars put up a 25-by-15-foot poster of Gesser on the side of a 10-story grain elevator in Dusty, Washington, on the road that ran from Pullman to Seattle. The cost? A mere $2,500, or 1/100th of what it took for the Ducks to have Joey Heisman’s likeness outside MSG.

“Jason and I still laugh about that,” Harrington said.

This was largely the playground of non-traditional powers or programs promoting non-traditional candidates, especially entering the 2000s. Sure, Ohio State would make a play for offensive lineman Orlando Pace in 1996, distributing magnets that brought the pancake block to the forefront, showing a stack of flapjacks with butter melting down the side. The reality is, during this era, the Michigans, Notre Dames, and USCs of the college football world didn’t need to do much to get the word out on their players.

Said Trojans SID Tim Tessalone to the Honolulu Advertiser in 2005, a year after Matt Leinart claimed his trophy and before Reggie Bush would go on to win, “they are going to get plenty of attention, anyway.”

But the schools that didn’t already have a fraternity within the fraternity of Heisman winners could be aided by the publicity. Hence, Marshall making Byron Leftwich bobbleheads in ’02; Memphis’s die-cast cars for running back DeAngelo Williams in ’05, which ran about $8 per car (the school shrewdly recouped that expense, selling another 1,500 cars for $30 apiece); Missouri’s Chase Daniel View-Master-style slide players that included a slide of Daniel’s highlights (those came at a cost of $25,000 for 2,500 of them); Boise State sending out “Ian for Heisman” DVDs in ’06 for running back Ian Johnson (a tactic Hawaii also did in ’07 with “A Colt Following” in hyping quarterback Colt Brennan), and Rutgers’s Ray Rice binoculars in ’07 that invited voters to “See Ray Run.”

This was the world in which Oregon’s anonymous boosters forked over a quarter of a million dollars to supply the football program and its star quarterback with prime real estate in the media capital of the world. Even if it didn’t bring the Ducks their first Heisman (something that, ironically, quarterback Marcus Mariota would do in 2014 with little to no push whatsoever), it aided the program in reaching the country’s upper echelon.

“I honestly think—and I’m not just saying this because it was something personal, and because of the actual physical side of it—it was one of the biggest and best marketing campaigns, definitely in Heisman history, but maybe in college football [history],” Harrington said in 2015.

That is, until Baylor went and completely changed the game ten years after Oregon’s billboard.

****

Heath Nielsen and the rest of Baylor’s football sports information department convened in the summer of 2011 eyeing a goal that—from a purely historical standpoint—seemed as likely as a blizzard hitting the Waco, Texas campus.

“Let’s get him to New York,” Nielsen said about Robert Griffin III, the Bears’ junior quarterback. “If everything falls our way, hopefully he can get invited as a finalist.”

To be fair, their task may have been even more far-fetched than a colossal snowfall. An average of 1.2 inches had fallen on the Central Texas city in the last thirty years and in the previous seventy-six Heisman votes, the school produced just two players who were in the top 10, QBs Larry Isbell (who was seventh in 1951) and Don Trull (fourth in ’63). Neither was really a factor, with Isbell taking twenty first-place nods, in coming in 1,614 points behind Princeton’s Dick Kazmaier, and Trull received twenty-nine firsts as he trailed Staubach by 1,607 points.

But on December 31, 1946, Waco had been bombarded with twenty inches of snow. So if Mother Nature could find her way to bring the unexpected to the Heart of Texas, well, Nielsen and Co. had a chance to do the same.

“We were just young and naive enough to try pretty much anything, and to just kind of be creative and go for silly stuff,” Nielsen said.

The preseason perceptions were an uphill battle. Griffin was eleventh in oddsmaker Bodog’s initial betting line, trailing Stanford’s Andrew Luck (9/2), Oklahoma’s Landry Jones (13/2), South Carolina’s Marcus Lattimore (7/1), Michigan’s Denard Robinson (15/2), Oregon’s LaMichael James (15/2), Alabama’s Trent Richardson (12/1), Oklahoma State’s Justin Blackmon (15/1), Boise State’s Kellen Moore (15/1), Arkansas’s Knile Davis (15/1), and Oklahoma’s Ryan Broyles (15/1). That put him fifth in the Southwest voting region and fourth among Big 12 players.

There was also an internal factor playing against Griffin. His coach, Art Briles, was initially reluctant, especially with the fact that his quarterback was only a junior. “I had to get coach’s green light before the season,” Nielsen said. “He is old-school enough that he’s not big into ‘Let’s highlight an individual and if you have to, let’s make it a senior.’”

But Briles—whose tenure in Waco would come to an end amid a sexual assault scandal in May 2016—relented, understanding the value a campaign had—much like Oregon with Harrington—in utilizing Griffin as a launching pad for Baylor. It was, after all, coming off a 7–6 season under its fourth-year coach, which amounted to its first winning record in fifteen years, and had capped it by being hammered by Illinois in the Texas Bowl 38–14.

“We didn’t have the success on the field, we didn’t have the television presence. We were going to do everything in our power—and not necessarily fan-wise—but to get that name to influential, key media,” Nielsen said. “The folks who were actually doing the talking and the sharing [of] the Heisman names. We wanted them to hear about our quarterback.”

But how? In order to overcome stigmas, Baylor’s staff knew it couldn’t follow normal campaign templates and be successful; the approach was going to have to be unique. So during those summer meetings, the rule was “Don’t laugh at any idea. Let’s put it all on a piece of paper.”

They began the push at Big 12 media days with a run-of-the-mill play: handing out a reporter’s notepad. It featured a photo of Griffin with his hands held high to signal a touchdown, and included branding of an RG3 shield and was littered with quotes from writers calling the passer the “fastest man to ever play quarterback in college football,” “like a magician,” “as exciting as there is in college football,” and “breathtaking,” to pick a few.

The reaction? There were some snickers.

“Baylor quarterback Robert Griffin is not going to win the Heisman,” a Star-Telegram writer proclaimed.

The school, though, was just getting started.

“My earliest thoughts were, ‘We’ve got to be somewhere in the digital/social realm, because that’s where the eyeballs are now,’” Nielsen said. “It’s funny sitting here in 2016, thinking back that doing a Facebook page and having a Twitter account was cutting edge, but it kind of was back then.”

The night of the Bears’ season opener against No. 14 TCU—which was coming off a Rose Bowl victory over Wisconsin—the school took the first step into that realm with a website promoting Griffin, BU-RG3.com. The quarterback responded by throwing a career-best 5 touchdown passes on 21 of 27 passing for 359 yards, ran for 38 yards on 10 carries, and even had a reception for 15 yards in a 50–48 victory.

“After we beat TCU, that’s when we kind of looked at our list and said ‘OK. We’re going for this,’” Nielsen said.

Along with making Griffin available to any writer—nationally or regionally—who wanted to talk to him, they created “RG3 for Heisman” Facebook and Twitter pages and did weekly YouTube videos entitled 30 with the THIIIRD, in which teammates would ask Griffin questions in rapid-fire fashion. Baylor used Facebook to allow fans to enter to win a prize package by sharing photos on their Facebook walls, but where the school truly set off a phenomenon on the platform was after Griffin passed for a program-best 479 yards and 4 touchdowns, including a 34-yarder to Terrance Williams with eight seconds remaining, to knock off No. 5 Oklahoma 45–38 on November 19.

A 59–24 loss to third-ranked Oklahoma State on October 29 dropped the Bears to 4–3, and Nielsen remembers people asking how much longer they planned on pushing Griffin with the wheels seemingly coming off Baylor’s season. “Which is a little awkward, because, let’s say your candidate isn’t going to do so well, how do you bow out when you dove in full-force?” Nielsen said.

But as Griffin’s star rose in national consciousness after that performance against the Sooners, it proved to be perfect timing and Baylor asked fans to “Join the Third,” which entailed attaching “III” to their names.

“That’s when it went from, a kind of what the institution is putting out there and aiming it at the media, and that’s when the grassroots, groundswell fan movement started,” Nielsen said.

Thousands of fans obliged, and five years later, it’s a movement that remains one of the more impactful tactics that Baylor employed.

“That really, really took off,” Nielsen said. “To this day, I can list out twenty things we did, and that’s the one thing that people remember. It’s just the ingenious, new thing, and it’s funny, because to this day there are still some Baylor fans that still have the III on their Facebook page. They never reverted to their real name.”

It was, in essence, brand building on a level few had ever accomplished in the nascent days of social media. Fans were engaged and voters educated, but Nielsen had a nostalgic streak that he wanted fed.

With nineteen years in the sports information game, he remembered the splash BYU made with its Detmer ties, and what Washington State accomplished by mailing out leafs. He wanted to capture that bit of Heisman campaigns past by giving media members something tangible as well.

A local businessman had caught wind that Baylor’s staff was looking to create something and approached Nielsen with an idea that fit that bill. He brought in a prototype of a Wheaties box that said “Heisman” across the top in place of the cereal’s name and featured an action shot of the quarterback. Where a normal cereal box would include a rundown of its ingredients, it had football references.

Nielsen opened the box and inside was cereal, along with a prize—a small video screen that could be loaded with highlights of Griffin.

“I was like ‘Wow,’” Nielsen said. “He was really selling me on it.”

The SID already had one idea in mind from their summer brainstorming session, a series of football cards, which in taking into account printing costs, shipping, and supplies, was estimated to run $10,000. With the school working off a list of upward of 700 voters they had identified, the entire run of cards would work out to 12 to 18 cents each. As he took in the box and the working MP4 player he asked the man,

“How much would this cost?”

“Oh,” he replied, “it wouldn’t be that much. I think we could be able to produce these for about $60 each.”

“I’m not a math whiz, but my brain took a couple of seconds trying to multiply … and I’m trying to do the math of how much this would cost, and it was just crazy,” Nielsen said.

The idea wasn’t to send out the cereal boxes to hundreds of voters, just a few high-profile figures to get exposure on ESPN’s College GameDay or in the pages of Sports Illustrated—but it wasn’t that approach that Nielsen was looking for in trying to push a player at a program that had been a perennial doormat.

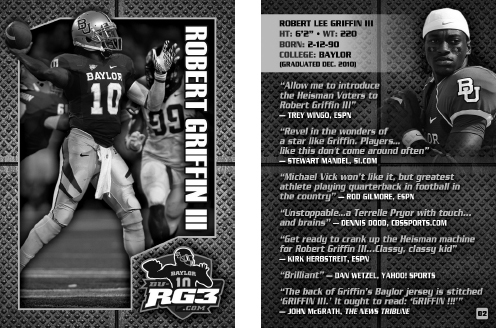

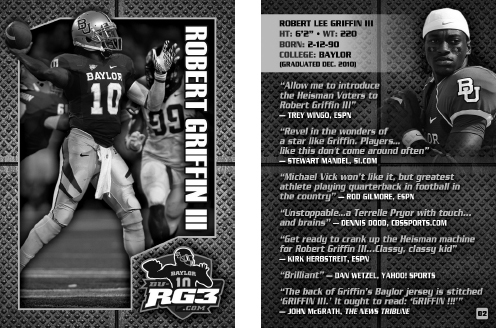

The front and back of one of the five cards that Baylor sent to Heisman voters to promote Robert Griffin III in 2011.

(Baylor Athletic Department)

“I was taking the other approach,” he said. “I wanted to hit everybody with something small rather than a big, expensive piece.”

Northwestern, another oft-overlooked school, had gone that route, putting the spotlight on quarterback Dan Persa by mailing out purple shoe-sized boxes that included two purple, seven-pound weights—he wore No. 7—that said “Persa Strong.” They arrived at the doorsteps of about seventy writers with an accompanying release that said “Persa Strong highlights Persa as the complete student-athlete. Strong on the field, in the classroom and in the community.”

Baylor would create five RG3 cards, mailed in plastic cases, with each having a different focus. The first, which was sent out days before the season opener against the Horned Frogs, was approached as a teaser of sorts, with one side featuring a close-up of the back of Griffin’s jersey and the RG3 logo. The other side said, “In the 2011 Heisman race, keep your eye on the third …”

One that included quotes from media members followed, and another was centered on Griffin’s success off the field, showing him receiving his undergraduate degree (in political science) in December 2010, and listed his academic awards. There was also a card that showcased Griffin the teammate, highlighting his offensive line and included the quote, “If I win an individual award, it’s based on what I’ve done with the guys around me. Without those guys, I’m nothing.” The final card was an action shot with the hashtag #JOINTHETHIRD.

The use of digital assets earned Nielsen and Co. acclaim, and while the football cards were another means of reaching those who maybe hadn’t embraced social media to that point, they ended up resonating more than Baylor’s SID could have expected.

“I will say, when it was all said and done, the part that surprised me the most, and I think the part that made the most impact was those physical football cards,” Nielsen said. “All it would take, you send them one in the mail, and they do their advertising for you, because they put it on their social account and then you’re getting exponential number of eyeballs seeing it, and just because you sent them a football card.… I actually think that old-school piece of it was really, really key.”

As was Griffin’s play. In throwing for 3,998 yards and 36 touchdowns to 6 interceptions, along with 644 rushing yards and 9 more scores, he was the nation’s only player with at least 3,000 yards passing and 300 rushing. His career numbers of 10,000 yards through the air and 2,000 on the ground made him the third player in FBS history to hit those numbers and the first from a major conference.

Griffin would win by 280 points over the preseason favorite Luck, garnering 405 first-place votes to 247 for the Cardinal quarterback. He also did it on a 9–3 team, tying Tim Tebow (’07) and Ricky Williams (’98) for the fewest victories by a winner since Tim Brown won at 8–4 Notre Dame in 1987.

“This is unbelievably believable,” Griffin said in his speech. “It’s unbelievable because in the moment, we’re all amazed when great things happen. But it’s believable because great things don’t happen without hard work.”

Griffin’s campaign was about fully embracing the right space at the right time. That same year, Stanford launched a microsite for Luck and also had a seven-minute presentation by coach David Shaw stumping for his quarterback, Oklahoma State had Twitter and Facebook pages for quarterback Brandon Weeden and Blackmon called “Weeden2Blackmon,” and Wisconsin had one for quarterback Russell Wilson (the Badgers would get a finalist that year, though it wasn’t Wilson, but rather running back Montee Ball).

“It wasn’t like we were breaking new ground, even though we get credit for stuff like that. I think we got a little bit fortunate timing-wise that that’s the way the world was turning,” Nielsen said. “We were on the front edge of that and were willing to push it hard. We did the Twitter, we did the Facebook, we did the full-blown website, a lot of the video portion of things.”

They also, more importantly, in helping to elevate the effectiveness of how they pushed Griffin, helped Baylor win.

That resulted in a 10 percent rise in donations to the Bear Foundation, the school’s licensing royalties rose more than 50 percent, and it saw increases in ticket sales, sponsorship deals, and its regional television contract. Per media measurement group General Sentiment, Baylor earned what amounted to $14 million in media coverage surrounding the campaign.

Baylor may not have reinvented Heisman hype, but it leveraged digital assets and the physical to set the stage for a new kind of campaign.

“[Griffin] winning that award on that evening in New York was the biggest athletic moment in Baylor sports history,” Nielsen said. “I don’t know that many would argue that it didn’t put Baylor on the map.”

These days, the brunt of campaigns are waged in digital fashion. Stanford launched WildCaff.com in 2015 for Christian McCaffrey, which included an ingenious 360-degree video experience of the running back on the field, and Oklahoma had a dancing, eight-bit version of quarterback Baker Mayfield in GIF form and used it with the hashtag #ShakeNBake. The old-school approach still has its place though, with Kansas State focusing on finalist-to-be Collin Klein’s toughness with a mailer that had an oversized Band-Aid; Northern Illinois promoted Jordan Lynch—who made it to New York in ’13—with a lunch box; Nebraska created Ameer Abdullah AA batteries (or more specifically, AA8s, to highlight the running back’s number) in ’14, with a package that included a warning label that said the Cornhusker “can cause shock to opposing defenses” and “prolonged exposure could cause an explosion on the national scene”; and in ’15, Colorado State sent out 500 packages of microwave popcorn to hype up wide receiver Rashard “Hollywood” Higgins.

“I think that is still super effective,” Nielsen said. “If everyone is going digital now, that might do a little bit more to make you stand out because of their rarity.”

If Joey Harrington represents the extremes of Heisman campaigning, Griffin is the antithesis, fueled by a largely viral push with a price tag of less than a tenth of Oregon’s in 2001.

Their paths would cross in 2014, when Griffin—on an off-day from the Washington Redskins—was back in Waco for the opening of McLane Stadium and the unveiling of his statue. Harrington, meanwhile, was part of FOX Sports 1’s broadcast team for the game.

Griffin was walking through the press box when Nielsen stopped him and took him over to meet Harrington and the rest of the TV team as they were eating and compiling pregame notes.

The two quarterbacks struck up a conversation when Harrington told him, “You went all the way and got the award I was trying for.”

“Yeah,” a nearby Nielsen chimed in, laughing. “I think he had a better SID than you did.”