4

The Forgotten Fear of Registration

The drama of the census

One of the largest protest movements in the history of West Germany took shape in early 1987. Coordinated by the Green Party, up to 1,500 “initiative groups” were formed throughout the country, and hundreds of thousands of participants gathered at demonstrations. The cause of this collective protest was the national census that was scheduled to begin on May 25 that year. “Few efforts on the part of the Bonn government have incited so much resistance and aggression,” wrote the Spiegel magazine about the plan to take stock of approximately 25 million households by means of some 600,000 official census takers.1 The acts of resistance were varied and inventive. One night before a soccer match, an unidentified group of people broke into the stadium in Dortmund and painted the words “Boycott the census” on the playing field. Because there was not enough time to remove this message before the opening whistle, officials changed it to “Don't boycott the census” in a desperate effort to promote the upcoming event. In West Berlin, activists gathered at the border of the divided city and, indifferent to the threats of fines, glued all of their survey forms to the Berlin Wall. The initiative groups distributed countless pamphlets and brochures listing strategies for sabotaging the mechanical readability of the census forms (cutting their edges, spilling coffee on them, etc.).

All of this protest energy was released because, in the eyes of many, the planned survey was at odds with the fundamental rights of the democratic state. In their preface to a book titled Was Sie gegen Mikrozensus und Volkszählung tun können [“What You Can Do Against the Micro-Census and the National Census”], which sold more than 250,000 copies by April of 1987, the editors mention, for instance, “a tightly woven surveillance network that will soon be draped over all citizens.” “The goal,” they continue, “is the total surveillance of everyone and the control of future behavior. A fundamental precondition for this is the comprehensive registration of all the data concerning the population.”2 Later on, they state in a similar vein: “The datafication of the entire population of the Federal Republic of Germany will form the material basis for total social control. And control is the first step toward manipulation.”3 All of the key words of the critique against the census can be found in this work and are repeated page after page: “registration,” “control,” “surveillance,” “manipulation.” It was the concern of the census's opponents that it would ultimately enable the police and the government administration to treat individuals as passive objects. “Almost without noticing, we are all being turned into puppets,”4 the editors point out with a frequently used metaphor: “We must defend ourselves against government measures to degrade us into externally controlled puppets.”5

The protests in 1987 were a continuation of an intense conflict that had begun four years earlier. According to the original plan, the census, which was to be the first since 1970, was scheduled to commence on April 27, 1983. Yet the unanimously ratified “Census Act,” which the West German parliament passed in early 1982, encountered unexpected popular resistance just a few months before the process was set to begin. The census, as the President of the Federal Statistical Office commented at the time, “has become an object of public debate to a greater extent than anyone involved had anticipated.”6 By March 1983, the Federal Constitutional Court had received more than 1,200 appeals claiming that the forthcoming census represented a violation of basic rights (including the right “to the free development of one's personality” and the right to “freedom of expression”). One of the latter, which had been submitted by two lawyers and a law student from Hamburg, was heard in court, and on April 13, just two weeks before the process was set to commence, the judges in Karlsruhe suspended the census on account of its unconstitutionality.

In their final ruling, which was issued in December 1983, the judges mandated that any future census activity would have to conform to the “supplementary legal regulations for the execution and organization of data acquisition.” Thus the “General Right to Personality” (Allgemeines Persönlichkeitsrecht) stipulates that “no connection can be made between collected data and any individualizable person or group of persons.” Unlike with the census of 1970, however, it was now possible to establish such connections by means of the new “technical preconditions of data acquisition and data processing.”7 Interconnected at the state and federal levels, electronic registries of the population would have made it possible to identify the personal information provided by any given citizen, and it was precisely this permeability, which the government expressly hoped to build into the new census, that the judges deemed illegal. In the ruling from December 1983, this skepticism about the census's constitutionality even led to the formulation of a new law, namely the aforementioned “right to informational self-determination,” which was intended to guarantee the protection of human dignity in the age of electronic data processing. In Germany, this basic right ultimately gave rise to the public discourse about “data protection” and provided guidelines for reformulated census procedures.

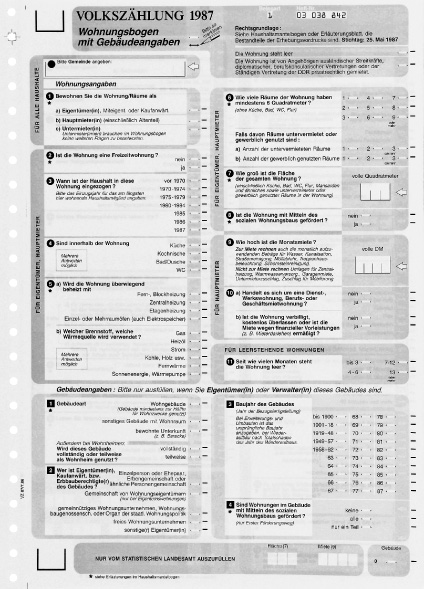

The provisions of the Federal Constitutional Court were incorporated into the census documents from 1987, which consisted of a “personal form,” a “residential form” and a “household form.” Compared with the census planned in 1983, fundamental changes were made to the way in which data would be collected and processed. The names and address of the members of a household, for instance, were no longer to be recorded on the back of the “residential form,” as had been the plan four years earlier, but rather on the new “household form,” which, after being submitted, would be separated from the other forms by officials. Its sole purpose, according to the text on the form itself, was “to ensure the comprehensiveness of the census; it will not be stored in electronic databases together with the personal form or the residential form.” In addition, citizens were now permitted to submit the forms to the authorities on their own instead of having to fill them out in the presence of a census taker, as had been expected in 1983. Finally, stricter guidelines were put in place regarding the electronic processing of the data. On the cover page of the census forms, households were now informed that, in every district, “only the specially designated data collection office” will have access to the surveys: “No other administrative authority and no other municipal or regional agency will be able to view the personal information. It will not be possible to identify any individual on the basis of the information stored at the regional office.”8 The presentation of the new forms was clearly affected by the long debates over “informational self-determination.” By 1987, the government had decided to address the people in a tone of appeasement.

Yet what, exactly, did the state want to know that aroused so much collective outrage in the 1980s? For large portions of the population, the total of 33 questions on the surveys – 18 on the “personal form,” 11 on the “residential form,” with 4 supplementary questions for the owners or managers of buildings – represented an immense threat. During the weeks before May 25, 1987, the struggle against this threat led to the bombing of government offices in which the printed forms were being stored (in Leverkusen and Freiburg, among other places). The census bureaus in the state of Hessia, according to one official involved, thus had to be fortified “like Fort Knox.”9 Looking back at these forms today, now over 30 years after the protests, one might struggle to understand what all of the fuss was about. From today's perspective, that is, the questions on the “personal form” and the “residential form” hardly seem prying at all. In addition to the sort of information contained on any piece of ID, all the state wanted to know were a few things about one's education, profession, commute to work, apartment size and monthly rent. The most intimate information requested on the “personal form” was presumably the response to Question 14: “How much time do you typically need to travel to work or school/college?” Just a decade after the census, the first social networks began to request personal information of an entirely different order. As mentioned in my first chapter, the patent application for SixDegrees specifies that new members are encouraged to create a profile listing their “e-mail address(es), last name, first name, aliases, occupation, geography, hobbies, skills or expertise.”10 Even a fleeting comparison of these two methods of data acquisition reveals the great cultural divide that I have been discussing all along. When the opponents of the census were up in arms about the “comprehensive registration of all the data concerning the population,”11 and when demonstrators occupied all the public squares in Germany to rally against the “surveillance state,” these protests in fact took place on the basis of a data set whose banality is almost laughable from today's perspective. Every new member on Facebook discloses far more information simply by creating a profile.

The “residential form” from the 1987 census in West Germany.

What happened in such a short time? How is it possible to explain this rapid and profound change in the way that people deal with registering their personal information? Today, “registration” is no longer perceived first and foremost as an act of victimization – as a show of force executed by authorities such as the “state” or the “police.” For most people, on the contrary, it has become a productive activity. What had repulsed the opponents of the census – namely, the horrifying scenario of “surveillance” – has now been revived as a social virtue of “communication.” Over the course of this transition, the concept of transparency has also undergone a complete shift in meaning. Instead of implying something threatening, transparency is now an expected feature of ethical behavior. There is no longer any talk at all about “people made of glass,” for instance, though this and similar terms had been ubiquitous in the critical discourse of the 1980s. Today, the attribute of transparency is, instead, a sign of integrity.

The police as a catalyst of electronic registration

Measured by today's standards of data circulation, the resistance to the 1987 census looks almost pathological. The agitated voices yelling from podiums and the protest marches through the streets seem like quite hysterical reactions to the government's wish to know such things as the type of heating used in one's apartment or one's preferred means of public transportation. What was the source of all this outrage? Interestingly enough, the opponents of the census did in fact discuss the pettiness of the survey questions. One critical article from 1987 pointed out, for instance, “the undeniable harmlessness of the individual census data.” Even 30 years ago, that is, the nominal value of each individual piece of information was not a cause for concern; rather, the threat was thought to lie in the menacing potential of the data set as a whole. For, as noted in the same article, the triviality of the questions “conceals … the explosive nature of their multi-functional correlative possibilities.”12 With computer-based registration, it would be possible to divide, filter, compare and recombine the data sets, and this uncontrollable proliferation was what the protesters really feared. They had no faith at all in the government's assurances that, in accordance with the fundamental right to “informational self-determination,” severe restrictions would be put in place to limit the ways in which the data could be processed. The fact that the government guaranteed the anonymity of the information provided on the personal form and the residential form, for instance, was regarded by the resistance movement as an empty gesture. The reference numbers on the forms, according to the critics, “would make it possible to identify registered respondents at any time.”13

In retrospect, this fear of registration, which seems so alien today, must have been related in some way to the media situation during the 1970s and 1980s. It was during these years that various administrative bodies began to collect formerly dispersed documents – such as files, index cards, forms and protocols – into electronic “databases,” and this activity did not escape public attention. The integration of previously heterogeneous personal data, the purpose and potential applications of which were obscure, gave rise to a diffuse sense of concern. Thus, the censuses announced for 1983 and 1987 were simply especially prominent targets of an ongoing critique that had been aimed at various administrative transitions throughout these years. Around the same time as the 1987 census, for instance, similar resentments were being voiced about the creation of computer-readable ID cards and about the police sharing information with the Department of Motor Vehicles. The protesters against the census even managed to direct hostility toward the popularity of new media technologies such as cable television and teletext. In a piece of criticism bearing the dystopian title “Schöne neue Kabelwelt” [“Brave New Cable World”], for instance, Claus Fokke Wermann proclaimed: “Whoever participates is converted into data. Or, put another way, wherever there is teletext, there are data problems.”14 The editors of the anti-census book mentioned above (“What You Can Do Against the Micro-Census and the National Census”) made a similar point with familiar diction: “In the age of cable television and teletext, consumer behavior can be monitored and controlled … and the users of such technology can be manipulated in an effective and targeted manner.”15

Why, exactly, did the concepts of “registration” and “datafication” have such negative connotations in the 1980s? What is immediately striking is how often the opponents of the census referred to the crimes of National Socialism. In 1983, the Second World War was hardly a distant memory, and thus the critical reception of the planned census made a point to emphasize the excessive use of registration by the Nazi government. In their book The Nazi Census: Identification and Control in the Third Reich, which was originally published in German in 1984, Götz Aly and Karl Heinz Roth analyzed the administrative conditions behind the Holocaust and openly associated their main thesis – namely, that optimized registration practices enabled the persecution and killing of the Jews – with the census planned for 1983. They posed the questions, for instance: “Is not the simple abstraction of humans into mere numbers a fundamental assault on their dignity? By profiling individuals, does the temptation not arise to regulate and, as statisticians like to put it, clean them up?”16 And they understood these rhetorical questions both as a summary of their historical analysis and as an expression of solidarity with those protesting against the census at hand. Their main argument against censuses – that they “constitute an assault on the social imagination”17 – could be made all the more forcefully because the authors, on account of their expertise as historians, knew where such measures could lead. For, as their research revealed, “The registration and bureaucratic isolation of the Jews in Germany began with the census of June 16, 1933.”18 In 1987, Götz Aly once again underscored the topicality of the Nazi administration to the unfolding situation by publishing a summary of his book in a brochure opposed to the forthcoming census.19 In this context, the National Socialist state seemed to be an important point of reference because it demonstrated the latent dangers of unleashing the proposed methods of registration. The numerous evocations of the Third Reich served the same purpose in the work “What You Can Do Against the Micro-Census and the National Census.” To its editors, censuses and indiscriminate data processing – which blur the boundaries between politics, the government and the police – had been characteristic features of the Nazi dictatorship. When the constitution of the Federal Republic of Germany was created, “it was unanimously agreed that such a condition would never be permitted to recur. All of this seems to have been forgotten.”20

The crimes of National Socialism reverberated clearly in the West German protests against the censuses during the 1980s. However, because censuses had already been taken in 1950, 1956, 1961, and 1970 without any noteworthy resistance, this traumatic historical parallel could not have been the primary impetus behind the rampant fear of registration. Something must have happened between 1970 and 1983 to have altered the perception of “datafication” and to have caused people to distrust registration processes. As mentioned above, the shift was related to the media-technical innovations of the time and their earliest areas of application.

In which contexts did computer-generated knowledge about human beings first emerge in the public sphere? Who were the individuals whose registration and identification first prompted the authorities to install such expensive and expansive electronic apparatuses? These questions must be kept in mind in order to understand why the disclosure of personal information had become such a sensitive issue. In 1968, Horst Herold, the newly appointed President of the Federal Criminal Police Office in West Germany, published an essay titled “Organisitorische Grundzüge der elektronischen Datenverarbeitung im Bereich der Polizei” [“Organizational Principles of Electronic Data-Processing in the Field of Police Work”), in which he stressed that “the activity of the police has always been that of generating, processing, evaluating and transferring data.”21 At that time, the West German police archives contained around 15 million files that did not communicate with one another, and for Herold this represented a scandalous fragmentation of data that made it difficult to fight crime in a productive manner. In his opinion, the future effectiveness of the police force depended on integrating all of these loose files as comprehensively as possible. This would require, as he put it, “a comprehensive survey of all data relating to crimes and criminals in a systematized and mechanized form.”22 With respect to solving crimes, that is, he believed the most important factor was neither the brilliant intuition of a detective nor the persistence of a good patrolman but rather the efficient processing of information. A criminologist with Marxist inclinations, Herold maintained that “mechanization will lead to police awareness.”23 Horst Herold's computer-based expansion of police manhunting methods and his central role in the struggle against the Red Army Faction are well documented, and so there is no need to go into the details here. For my purposes, it is crucial to underscore that, in West Germany, computer-based knowledge about individuals and the systems implemented to collect this information (such as the “Inpol” database, which was introduced in 1972) were associated from the very beginning with hunting down criminals. Registering people electronically was synonymous with optimizing police investigations and verifying suspicions. It was the police who decided whose data should be “stored,” and the criteria for this decision were exceptionally broad because Herold's electronic manhunt focused not only on what people were doing but also on what they were not doing. As of the late 1970s, his groundbreaking innovation was to use computers to filter through lists of names and seemingly mundane personal information in order to identify perpetrators who lacked criminal records. Herold himself referred to this method as a “negative dragnet investigation,” and its aim was to “reduce, by processes of elimination, the police dataset to a small remainder of potential suspects.”24 With this investigative method, however, all sorts of marginal information about any unobtrusive individual could possibly raise suspicion. It was an approach by the police that involved, much like the censuses under protest, the acquisition of large volumes of data by means of distributed surveys.

To its critics, the computerized census represented nothing less than “totalitarian forms of digitalization,”25 and this fear was amplified in the middle of the 1980s by the seemingly prophetic representation of similar processes in works of literature. It seemed as though the most well-known dystopia in twentieth-century fiction, which had been written in the years after the Second World War, was about to become reality. George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four is mentioned in just about every article and pamphlet that was written in support of the protest movement. Especially in the spring of 1983, the forthcoming census was regarded as a sign that the horrifying world imagined by Orwell was about to be realized right on schedule. “The census scheduled for April 27, 1983,” according to one collection of oppositional essays, “is a timely catalyst for the fear and anger welling up in all of us about the actualization of Orwell's vision.”26 About the success of a pamphlet titled “Computer beherrschen das Land” [“Computers Will Rule the Country”], an article in the same volume declared: “Those who claim that we should fear the coming of an Orwellian surveillance state have hit the bulls-eye.”27 On the day after the Federal Constitutional Court had suspended the planned census, the main headline in the Süddeutsche Zeitung, a popular newspaper, was “Warten auf Orwells Jahr” [“Waiting for Orwell's Year”]. The literary representation of a totalitarian state in which “telescreens,” mounted on every corner, constantly monitor the population served as a convenient model in the media's coverage of the 1983 census – and likewise in 1987, even though the novel's imagined year had passed, the book continued to be a popular reference. Writing on the eve of that census, two critics remarked: “What Orwell's novel 1984 warned us about – a world of totalitarian surveillance, a world of terror and bureaucracy, of administrative mendacity and manipulation … this has become today's concrete reality.”28

The semantics of the net

Throughout all of this, the fear of being registered was tied to anxieties about the imminent “networking” of information,29 which, as far as the protesters were concerned, was the ultimate goal of the census at hand, and which had an accurate model in Orwell's fictitious state of Oceania. During the 1980s, the words “net,” “network,” and “networking” had unmistakably threatening overtones. The terms called to mind the expansion of a sophisticated and powerful authority whose sphere of influence was unclear. Beginning in 1979, the Spiegel magazine began to publish a long-running series of articles on “the path toward the surveillance state,” and it is no coincidence that the catchphrase of the series was “The Steel Net Is Draping Over Us” (“Das Stahlnetz stülpt sich über uns”).30 Whoever got caught up in this sprawling web of computer-aided data acquisition – or so the message went – would face reduced freedoms and threats to their identity.

It is interesting that, in the popular imagination, the semantics of the “network” were still vaguely negative even during the early stages of the internet. The 1995 film The Net, for instance, revolved around the latent paranoid potential that exists in the relationship between individuals and electronic media. Played by Sandra Bullock, the main character is a software specialist named Angela Bennett whose social isolation increases as she spends more and more time online. The young woman no longer has any family connections (her dad abandoned the family long ago, and her senile mother is in a nursing home); she works at home in a jogging suit for a software company based in another city; her love life is restricted to bland online chats; and she even orders pizza on the internet, which in 1995 was not yet a sign of a mobile urban lifestyle but rather an acute indication of loneliness. A day before she is about to leave on a vacation (her “first in six years”), Bennett discovers a hoard of secret documents on one of her employer's computer disks and soon becomes the target of terrorist computer hackers who manipulate the stock market. The group has to recover the disk (mobile data storage like the “cloud” did not yet exist at the time), and when they struggle to do so, the hackers gradually begin to delete Bennett's identity in order to put pressure on her. All of her forms of identification have been stolen, and suddenly she is no longer registered at the beach hotel where she is staying in Mexico. When she goes to the consulate to request a visa, the officials there take her for another person, “Ruth Marx,” and it is only under this name that she is allowed to return to the United States. Having flown back to California, she discovers that her car is no longer parked at the airport and that her house has been cleaned out and put up for sale by a woman named “Angela Bennett.” The film plays through the thought-experiment of what an isolated person, whose existence is more or less confined to online worlds, can possibly do to prove who she really is. Angela Bennett, who is friendless and works from home, has just one personal connection in all of Los Angeles, namely with her former therapist, who thinks that the story about her swapped identity is utterly delusional. Her adversaries, who have access to police computers and hospital records, change her fingerprints and give her a criminal record. When Angela Bennett is finally arrested, her entire profile matches that of a fugitive named Ruth Marx. Even the public defender assigned to her case regards her account of events as pure paranoia.

Because The Net is a conventional Hollywood movie with a happy ending, the protagonist is able to clarify all of the confusion in the final minutes. She exposes the ring of cyberterrorists founded by her employer; the real Ruth Marx is found dead; and her own true identity is re-established. In terms of media history, however, the film is interesting because it shows that the idea of “networking” computer-generated data could still conjure up a great deal of anxiety in 1995, and because of its depiction of what will happen if people begin to immerse themselves online. Everything about the film's representation of the main character is meant to suggest that, by interacting with others exclusively through computers, a person will put his or her entire existence at stake. While sitting on the Mexican beach with her open laptop, the shy Angela Bennett is addressed for the first time by a member of the hacker cell: “Computers are your life, aren't they?” “Yes,” she replies: “Perfect hiding place.” Shortly after becoming a common component of everyday life, the internet was regarded as an anti-social network – the lives of vulnerable subjects could be destroyed by this web of data. “Our whole world is sitting there on a computer,” Bennett explains to her lawyer (in terms that call to mind the brochures produced by the census protesters): “It's like this little electronic shadow on each and every one of us, just, just begging for someone to screw with.”

The glamour of datafication

At the same time as movie-goers were able to watch Sandra Bullock struggle against her own demise, an entirely different notion of the electronic “net” was gaining ground. Far from regarding “registration” as something threatening, this latter interpretation rather associated it with the productive potential of data-driven identity. The first online dating sites were founded; the patent for the SixDegrees network was submitted; the books by Howard Rheingold, Nicholas Negroponte, and Sherry Turkle celebrated the liberating and self-determined nature of virtual communities; and the early European “net criticism” formulated by Geert Lovink, Pit Schultz, and others, though oppositional to those who praised unsullied “cyberspace” without restraint, still resembled the Californian internet pioneers to the extent that it likewise emphasized the active qualities of participating on the “net”: “Net criticism, as Pit Schultz and I have defined it,” claimed Lovink in 1996, “does not want to take the outsider's point of view. It positions itself within the Net, inside the software and wires.”31 During the dawning age of digital culture, the internet was no longer thought to produce sociophobic loners like Angela Bennett, but rather socially integrated citizens – engaged “netizens” (in the neologistic lingo of the late 1990s). While it may be true that, today, to be “networked” is no longer suggestive of external control but is rather understood as a performative act, as a communicative skill without which it would be impossible to have a career or a fulfilling social life, it should be kept in mind that these positive connotations are barely 20 years old. The “net” of electronically integrated data is no longer perceived as a threat to our existence; in both the market-oriented and critical rhetoric of digital culture, it is regarded instead as a catalyst and as a malleable piece of infrastructure. If anything, one could say that the discussions of “networks” and “registration” over the past 20 years have been characterized by their remarkable lack of paranoia.

The thoroughness of this transition becomes clear when one compares the deeply felt unease regarding methods of data circulation, which repeatedly came to the surface in Germany during the 1980s, with today's standards of behavior. In 2011, an EU-wide census was taken (the first in Germany since 1987), and it did not incite any dissent. Everyday methods of self-datafication – in the form of social-media profiles, location services on smartphones, or mobile body measurements – have become so entrenched in society that the information requested by a census hardly seems to pose a threat. As mentioned above, proponents of the quantified-self movement consider measuring and counting to be formational aspects of their identity. If Fitbit's website can openly claim that the “Flex” wristband “tracks every part of your day,”32 then ubiquitous registration is no longer a horrifying scenario but, rather, a public service.

This fundamental shift in collective mentality is undoubtedly related to the various types of entities that have demanded our registration. During the 1980s, it was the government whose requests for information, in the form of a census, engendered so much distrust in so many people. To be registered by the “state” was synonymous with forfeiting the autonomous core of one's own personality, converting human dignity into bar codes, or being “regulated” and “cleaned up,” as Götz Aly and Karl Heinz Roth put it in 1984.33 If one reads through the discreetly placed “privacy guidelines” of companies such as Facebook, Instagram, or Snapchat, which can only be discovered after a long series of clicks, it immediately becomes apparent that the information in one's profile is processed and disseminated in a number of ways that are not clearly explained. And yet the emotional response of those using social media (which is almost every single person in countries such as Germany and the United States) is the exact opposite of the registration phobia of the 1980s. To be converted into data by the global corporations of digital culture is typically not a cause of paranoia and anxiety – rather, it is associated with a sense of belonging. Here there is no risk of being caught in the cold tentacles of the state; it is really about being part of a community of users. In the history of media technology, perhaps no piece of foundational rhetoric has had a more lasting effect than the discourse about self-development and community formation during the early years of the internet – bromides that live on today in every keynote speech delivered by Mark Zuckerberg and in every cozy advertisement for Airbnb. The promise of being together with others via one's “timelines” and “stories” overshadows all of the ongoing transactions that take place between users and providers, even though the companies’ business model of acquiring and sharing personal information can be understood as a refined and opaque version of the very governmental registration practices that had incited so much resistance during the 1980s.

It is just this sort of interrelational nexus that makes Michel Foucault's analyses – from his early concept of the “microphysics of power” to his observations about “governmentality” in his later lectures – so useful for understanding the human image in digital culture. For, given that his pioneering Marxist critique, with its clear division between suppressors and the suppressed, was meant above all to draw attention to the ubiquity and placelessness of power relations, then the comprehensive expansion of registration processes over the past quarter-century – from the intermittent censuses mandated by state authorities to the omnipresent data surveys on the internet – corroborate his theories in an unexpected way. After 1989, with the collapse of the socialist states and the end of the Cold War (events that were remarkably synchronized with the rise of digital culture), the traditional agents and instances of political power in Europe and North America lost a great deal of their former visibility. During the 1990s, this diminished position was also reflected in the notable decline in protest movements against the “state.” At this same time, increasingly deregulated private corporations began to adopt the government's registration techniques and integrate them into digital communication technologies. These new relations no longer fit the understanding of power that fueled the political critique and the protest movements from 1968 until the end of the 1980s; it is no longer possible to draw a clear distinction between the suppressor and the suppressed, between the registering body and the registered. In the early 1990s, publications such as the magazine Wired helped to breed an unexpected alliance between internet activists, who came from the Californian counter-culture, and conservative liberal-market politics. These two spheres came together in their common desire to defend the establishment of digital infrastructures from government regulations.34 The computer-aided registration of human beings has thus proliferated in many ways, but the social and political dynamics surrounding the circulation of personal information have taken shape in a way that was totally unforeseen.

Nineteen Eighty-Four from today's perspective

The extent to which the current situation differs from that of the 1980s becomes especially clear when one revisits the obligatory reference from that time – George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four – from the perspective of today's media reality. Compared to the present day, it is amazing both how similar and how dissimilar Orwell's imagined world is. If, 30 years ago, the countless critics of the census who feared the imminent arrival of the fictitious “surveillance state” could have known about all of the technological developments to come, they certainly would have felt as though their fears were justified. For, in the early twenty-first century, the presence of networked screens in every apartment, in every subway station, and on every street corner reached a degree of density never achieved in Orwell's post-apocalyptic and war-torn Oceania. “The telescreen received and transmitted simultaneously,”35 the novel informs us about the monitoring devices installed all across London. News, instructions, and motivational songs from the Party are broadcast into every apartment “from an oblong metal plaque like a dulled mirror which formed part of the surface of the right-hand wall.”36 This instrument, the narrator explains, “could be dimmed, but there was no way of shutting it off completely.”37 In Nineteen Eighty-Four, every human movement is recorded by the displays – “Whichever way you turned, the telescreen faced you”38 – and this total surveillance is coupled with the government's insistence on constant social interaction. “It was assumed,” writes Orwell about the expectations of a Party member, “that when he was not working, eating or sleeping he would be taking part in some kind of communal recreation: to do anything that suggested a taste for solitude, even to go for a walk by yourself, was always slightly dangerous.”39 Unrecorded activity raises suspicion, and a “taste for solitude” is regarded as a latent pathology: in the debates from 2012 about potential mass murderers and their supposed preference to abstain from Facebook, this imperative to socialize looks awfully familiar.

In light of the present state of media technology, it is safe to say that Orwell was quite prophetic (though he was a few decades off the mark), and it is telling that sales of Nineteen Eighty-Four tend to spike during times of political crisis, as they did after the election of Donald Trump at the end of 2016. Taken on their own, however, these occasional similarities are not very significant. Of far greater interest are the fundamental differences that exist between the political context of the novel's dystopian world and the circumstances today. Today, almost everyone in North America and Europe lives in a free and democratic state (recent political developments notwithstanding). There is no totalitarian surveillance regime controlling the activities and thoughts of its subjects and punishing every transgression with drastic measures. Instead of the tyrannical state envisioned by Orwell, the center of data circulation in today's media reality is composed of an array of discrete providers: a series of publicly traded global corporations that are not perceived as being oppressive even though they presumably possess more information about people than any secret service ever could.40

In Nineteen Eighty-Four, the seats of power are visible at all times and can be located with precision. The gigantic buildings that house the “Ministries,” which resemble those of National Socialism, loom over the city of London: “So completely did they dwarf the surrounding architecture that from the roof of Victory Mansions you could see all four of them simultaneously. They were the homes of the four Ministries between which the entire apparatus of government was divided.”41 The personnel structure of this apparatus is a system of concentric circles, with “Big Brother” in the center, then a close ring consisting of the elite members of the “Inner Party,” who have access to the telescreens, and finally the marginal and oppressed bulk of the population – the so-called “Outer Party” to which the novel's protagonist, Winston Smith, belongs. Within this hierarchical system, the use of electronic media is only conceivable as a measure of control wielded by the state authorities: “With the development of television, and the technical advance which made it possible to receive and transmit simultaneously on the same instrument,” the narrator explains, “private life came to an end. Every citizen, or at least every citizen important enough to be worth watching, could be kept for twenty-four hours a day under the eyes of the police and in the sound of official propaganda.”42 Registration, recording, and police investigations are one and the same in Orwell's novel, and this conflation results in a human image of total uniformity. For, as soon as the system of telescreens was put in place, “The possibility of enforcing not only complete obedience to the will of the State, but complete uniformity of opinion on all subjects, now existed for the first time.”43

The surveillance regime in Nineteen Eighty-Four is intended to eliminate any and all sorts of individual development. Oceania is inhabited by “[t]hree hundred million people all with the same face.”44 They all eat the same cabbage soup, wear the same jacket, are awakened at the same time every morning by the telescreen, and occupy the same prescribed world of thought. In his novel, Orwell depicted a sort of fascist or Stalinist totalitarianism that has been optimized by way of media technology. Yet this horrifying vision, which seemed plausible in the aftermath of the Second World War (and still resonated in the 1980s), never came to pass. Today, ubiquitous registration is no longer perceived as something coercive but is rather a voluntary aspect of the new media reality; the decree of uniformity has been replaced by an insistence on individual self-development. Whereas the telescreens in Nineteen Eighty-Four, which are “delicate enough” to register a person's heartbeat,45 do so in the name of control, today's wearables and smart watches, which perform the same task, are used to satisfy a collective desire for self-quantification. The emblem of datafied life in Orwell's novel is the pallid and subdued Party member who is worn down by constant surveillance. Who would Winston Smith be in today's digital culture? The young man in the café taking selfies in the now-familiar pose and quickly posting these pictures on Instagram to provide his followers with new images? The man jogging in the park, with a tracking device in his shoe and a Fitbit around his wrist, who plans to upload his step count and heart rate for the whole community to see?

Instead of smothering our identities, today's processes of datafication define their shape and representation. In Orwell's novel, one of the tactics of the despotic regime is to deprive people of their personal memories. Keeping a diary, for instance, is an offence punishable by death. Without being able to call to mind your own biography, as the narrator says about Winston Smith, “even the outline of your own life lost its sharpness.”46 For Smith, the act of circumventing this memory ban and writing down his own impressions is a form of inner resistance, as are his rendezvous with his lover Julia. Because Party members are only permitted to procreate by means of artificial insemination, sexual desire is regarded as a “Thoughtcrime” in Oceania. Ultimately, sex is a form of protest: “Their embrace had been a battle, the climax a victory. It was a blow struck against the Party. It was a political act.”47 This fusion of sexual and political liberation surely contributed to the novel's success after 1968. At its core, subversion in Orwell's work means finding refuge from telescreens and microphones. According to the ethics of the novel, the sphere of humanity is unrecordable and unrecorded. After a (presumably) furtive tryst with Julia, Winston emphatically declares: “They can't get inside you. If you can feel that staying human is worthwhile, even when it can't have any result whatever, you've beaten them.”48 Referring to the Party's informers, the narrator adds: “They could lay bare in the utmost detail everything that you had done or said or thought; but the inner heart, whose workings were mysterious even to yourself, remained impregnable.”49 Individuals are only able to preserve their human dignity in areas beyond the reach of electronic data acquisition – a credo or axiom of humanity that the opponents of the West German census would adopt 35 years later. Such opposition has dissipated in the far-reaching agendas of today's digital culture. Today, human beings are chiefly defined by the extent to which they convert themselves into data and communicate this information via digital media. The ego has become a profile.

Meanwhile, the formerly horrifying world depicted in Nineteen Eighty-Four has become nothing more than an ironic reference in 21st-century popular culture. Big Brother, which debuted in the Netherlands in 1999 and became an international franchise the following year, is a surveillance show that still entices tens of thousands of auditions for every new season (even though the popularity of the program has waned to such an extent that its contestants seem to sit around attracting as much attention as Kafka's hunger artist). Another reference to Orwell concerns his portrayal, toward the end of Nineteen Eighty-Four, of the Party's torture practices in Room 101 of the “Ministry of Love,” which everyone in Oceania fears and which Winston Smith himself has to experience after his denunciation. “The thing that is in Room 101 is the worst thing in the world,” says O'Brien, the mysterious Party official, as he leads Winston into the torture chamber: “The worst thing in the world,” he goes on, “varies from individual to individual. It may be burial alive, or death by fire, or by drowning, or by impalement, or fifty other deaths. There are cases where it is some quite trivial thing, not even fatal.”50 A guard enters the room carrying “a box or basket of some kind,” and begins to prepare Winston's torture session:

It was an oblong wire cage with a handle on top for carrying it by. Fixed to the front of it was something that looked like a fencing mask, with the concave side outwards. Although it was three or four metres away from him, he could see that the cage was divided lengthways into two compartments, and that there was some kind of creature in each. They were rats.… “You can't do that!” he cried out in a high cracked voice. “You couldn't, you couldn't! It's impossible.”51

O'Brien begins to set the torture process in motion; he fastens the delinquent to his chair and places a mask over his head that is attached to a cage full of rats, which are now separated from Winston's head by two partitions. He then lifts the first partition: “Again the black panic took hold of him. He was blind, helpless, mindless.”52 It is unknown whether the creator of the popular television program I'm a Celebrity … Get Me Out of Here! had been familiar with this scene from Nineteen Eighty-Four when he came up with the show's so-called “Bushtucker Trials,” in which the heads or entire bodies of the contestants are placed in glass boxes which are in turn filled with rats, mice, or insects. The similarity of the design is uncanny, and whereas Winston is able to save himself at the last second from actually coming into contact with the rats by betraying his lover Julia, the celebrities in the jungle endure the challenge and proudly return to camp with the “stars” that they have earned for their suffering (these can be exchanged for more appetizing food and drink on the show). In Nineteen Eighty-Four, as the character O'Brien says, this sort of mechanism produces the same amount of fear as potentially burning to death, drowning, or being impaled, and although Winston Smith survives the procedure physically, it completely breaks his will to be free and extinguishes his inner life. The viewers of I'm a Celebrity, in contrast, regard the image of rats scrambling over someone's encased head as something routine, and the journalists who write about trashy television nonchalantly discuss whether this year's season is more entertaining than those of the past.

Stigmatization and self-design

In multiple ways today, previously despotic forms of empowerment function as means of expressing subjectivity – a transition that each of the chapters of this book has illustrated with various examples. Formerly a disciplinary instrument, the profile has emerged as a method of self-representation. The use of technology to locate individuals, which just ten years ago was primarily restricted to the contexts of law enforcement and criminal justice, is now an essential precondition for social transactions, popular games, and finding a romantic partner. Finally, measuring the body, which in the human sciences was likewise motivated by the desire to register deviant subjects, now promises in the form of wearables and health apps to contribute to our sovereign and self-determined existence. All of these methods of self-tracking have stripped the practice of registration, which prompted collective protests just 30 years ago, of its menacing connotations. No longer is it an authoritarian and opaque authority that collects data about the lives, locations, and bodies of individual people; the registering authority and the registered have rather melded into one, and they enhance the so-called “liquid surveillance” that Zygmunt Bauman and David Lyon have recently identified as a major feature of digital culture.53 Of course, digital culture allows us to make our own decisions. The circumstances are not those of a fictional or actual dystopian or authoritarian regime. No one is forced to create a social-media profile, use location-based services on their phone, or even to own a smartphone at all (even though the refusal to do so would result in being excluded from more and more spheres of communication and activity). As the initiatives of digital activists have shown, it is also possible to enjoy the perks of the latest media technologies while remaining vigilant against the registration, identification, and location techniques employed by large corporations. Finn Brunton and Helen Nissenbaum's 2015 book Obfuscation, for instance, offers excellent tips on how to obscure one's personal information.54 That said, the fundamental shifts that have taken place over the last 25 years in the relationship between subject-formation and registration techniques have caused these alternative options to fade into the background. Even Edward Snowden's revelations from 2013, which clearly showed that today's governments have access to previously unthinkable amounts of their citizens’ personal information, incited no more than a brief stint of public outrage. This eye-opening knowledge simply cannot compete with the universal narratives of “sharing” and being “social.” It is one of the paradoxes of digital culture that, in an era when such large amounts of personal data are being controlled by outside entities, the rhetoric of self-determination is flourishing more than ever.

This gesture of autonomy, moreover, has not been restricted to data-driven forms of subject-formation – it pertains just as well to the immediately physical phenomenon of the human body. As with the development of the profile format in digital culture, over the past 20 years the presentation of one's own body – in particular, one's own skin – has been influenced by a technique that was once used to stigmatize individuals. Of course, I am referring here to the astounding popularity of tattoos. As recently as 1984, the following remarks could be found in a reference work for police: “Tattoos are common among sailors, soldiers, workers, and prisoners. In port cities, there are often special tattoo parlors.… From the perspective of criminology, tattoos are of interest above all as identifying features in personal descriptions. Moreover, they often reveal things about the origin and social environment of those who have them.”55

Various functions have been attributed to tattoos throughout the history of law enforcement. Up until the late eighteenth century in Europe, in fact, having a tattoo was equivalent to being stigmatized; convicted criminals were given a mark of shame, such as the flower tattooed on Milady de Winter's shoulder in Dumas's novel The Three Musketeers. This form of punishment came to an end in the decades around the year 1800. The tattooed criminal body, however, gained renewed significance with the rise of criminal anthropology during the middle of the nineteenth century. At this point, they were no longer relevant as stigmatizing symbols imposed by the authorities but rather as potential clues to a criminal's motives. Cesare Lombroso, who while working as a prison doctor during the 1870s, supposedly studied the tattoos of more than 7,000 inmates,56 discusses them again and again within his intricate classification system. He associated particular patterns with particular criminal types, and he attributed the commonness of tattoos among criminals to their greater tolerance of pain and to the general tedium of prison life. Hans Gross added to this discussion in his Criminal Investigation: A Practical Handbook. It was not necessary, he thought, to “go as far as” Lombroso and his followers, who considered “tattooing the characteristic sign of habitual criminals.”57 Nevertheless, he agreed with the criminal-anthropological school in his belief that “Tattooing will generally be met with among people of an energetic disposition: … soldiers, sailors, butchers, fishermen, woodcutters, smiths, etc.” He believed that the reason for this proclivity was not their high threshold for pain but rather their heightened “sexual sensitivity”: “[I]t is for this reason that among persons of the feminine sex tattooing is in Europe generally only found among prostitutes.”58 As regards criminology, this meant that tattoos were more common among criminals of a similarly energetic sort, “such as murderers, hooligans, house-breakers, etc., and on the other hand among people of a sensual nature such as bullies, sodomites, ravishers, and others who commit crimes against morality, but not among cheats and thieves.”59

By the end of the nineteenth century, the notion of the tattoo as a violently applied mark of shame had long been rejected. Alphonse Bertillon dismissed the question of why his anthropometric system did not include such a category with the following words: “Treating tattoos as a sign of criminality would be a covert reintroduction of stigmatization, and I strongly object to such an imposition.”60 With the glaring exception of tattooing inmate numbers on the prisoners at Auschwitz, this practice was otherwise never revived in the twentieth century. Nevertheless, police investigators maintained an interest in what tattoos might reveal about criminal motives, as is evident from the 1984 reference work cited above. That article had been written toward the end of an era in which tattoos could still be treated as stigmatizations with classificatory significance. Just a few years later, the third epoch in the European history of tattoos began to take its course, and this involved their transition from signs saturated in meaning to purely aesthetic elements of self-design. Now it is no longer the criminal or prostitute, the pederast or rapist, whose skin is covered in ink; rather, tattoos can be found on anyone and in every location: the secretary at the office, the professional athlete at the stadium, the family man at the public pool. Over the past few decades, tattoos have been purely decorative; they are no longer indicative of someone's deviant background, and they certainly do not “reveal things about the origin and social environment of those who have them,” as they still did some 30 years ago.

In certain contexts, however, tattoos are still used to define identities and signify that someone belongs to one group or another. Since the middle of the 1990s, for instance, Nike has encouraged employees at its flagship stores to have the “swoosh” logo tattooed somewhere visible on their bodies – not under coercion, and not as a job requirement, but simply as a symbol of their identification with the brand.61 This request – this “covert reintroduction of stigmatization,” as Bertillon put it – illustrates the transformation that this book has attempted to delineate all along: formerly coercive methods of registration have become voluntary methods of self-styling; the constrictive procedures of the police and the criminal justice system have been refashioned into the free and cheerful tools of marketing.