OTHA TURNER’S FIFE AND DRUM PICNIC

Otha Turner’s fife and drum picnic is what you’d want to see if you could go back in time. When I feared that to find work I’d have to leave Memphis, the experience I knew I’d miss most was the summer fife and drum picnic. There were two, both in Gravel Springs, Mississippi—a town small enough not to be on most maps. One picnic was in July behind L. P. Buford’s crossroads store—I’ve lost my flyer pulled from a pole on a desolate gravel road that announced, “There will be drumming.” The other picnic was around Labor Day in the nearby side yard of fife player Otha Turner’s farm. These picnics seemed ineffable even when standing in the middle of one, like trying to touch an echo.

Otha’s picnic was decades running. His farm, with its leaning tarpaper shack, the small barn behind, a large garden for personal crops, a white horse with its tail swishing—it was like a movie set of a small independent farm. Neighboring trailers and homes were far apart, and at night in Otha’s holler, dark quiet encircled everything. When Otha played the fife—he called it a “fice”—it was just a change in the air, his breath through a piece of bamboo pushing into the dust and night that hung so close. It was like a bird’s beautiful chirp, an ascension, a dawning, and when the drums fell in, sticks beating on animal skins, the simple music assumed massive power, making listeners fall in the line that falls behind the piper, to dance with Gabe, the archangel.

Otha Turner and the barn behind his house. (Courtesy of Yancey Allison)

These notes accompanied the first album by Otha Turner and the Rising Star Fife and Drum Band. Many people assume all of Mississippi music sounds like the blues made famous in the Delta, but the north Mississippi hill country has a distinct tradition. Music is the aural expression of place, a geyser emitting sound instead of water. Time was, the way a person sang a song—“61 Highway,” “Joe Turner,” or any of what we call “folk” songs—was like a spoken accent; it told where in the area they lived. The vast, alluvial Delta sounds very different from the nearby hill country, where the land is stony and arable only in patches instead of huge swaths. Driving through the Delta, the long tilled rows and the limitless horizon have a way of suggesting Robert Johnson’s forlorn blues and Son House’s piston-fired guitar strokes. In Tate and Panola counties, Mississippi, it’s dust and trees, and the fife and drum sound seems sprung from them. (In Junior Kimbrough’s Marshall County, they drone.) And this is not your Revolutionary or Civil War martial music, even if the instrumentation is similar; the black rural fife and drum sound evokes an African connection like no other American music.

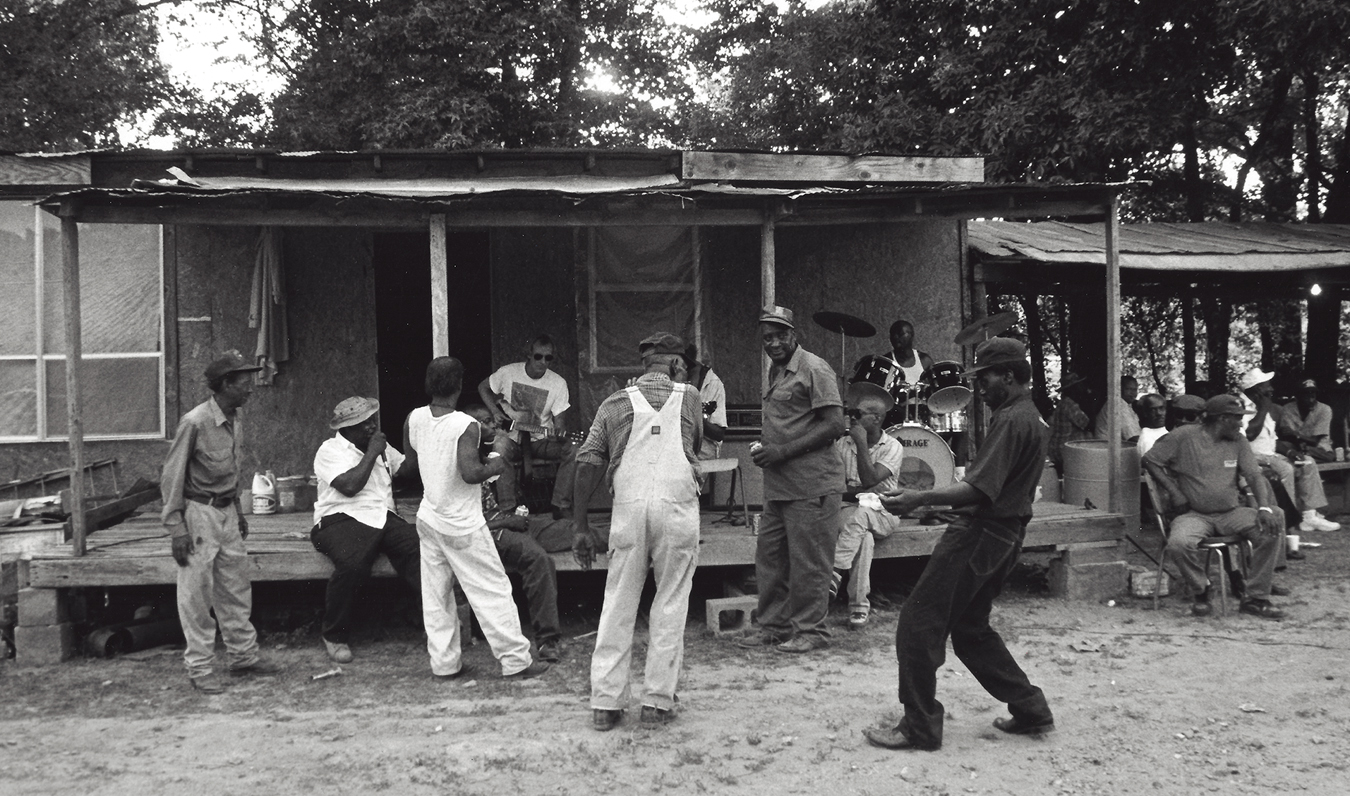

As Jim Dickinson’s sons, Luther and Cody Dickinson—the North Mississippi Allstars—grew up, they helped organize the picnics. Soon there were three stages—a flatbed for the electric bands, a porch stage for the acoustics, and the parched middle for the fife and drum. Otha wore a wireless lavalier microphone so the fife sound was amplified, piercingly pure in that night air. Guests paid a cover charge, which assured Otha’s family was getting some real return on all their effort.

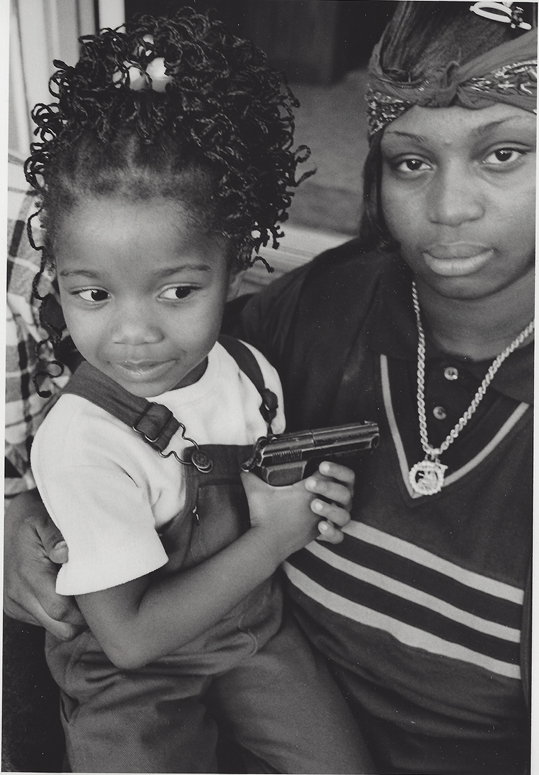

My passion dimmed after two gun incidents, both at the L. P. Buford’s location, not Otha’s. The first was at nighttime. Suddenly two men were in a tussle, their forearms locked and forming a tall triangle, a pearl-handled pistol atop like a Christmas tree star. The man on the right was trying to bring his forearm down 90 degrees so the pointed barrel could kill. The man on the left worked hard to keep that arm up, and the opposing exertions swung them circular, like clumsy dancers. Locals separated the men. Time moved thickly through the scuffle. I don’t recall a shot fired, but the party was over.

Guns in Mississippi. Guns in America. (Courtesy of Yancey Allison)

The second incident was a summer or two later, in the early 1990s, during broad daylight. Crack was at epidemic levels across America, and part of why I’d left the Northeast was the random violence the drug created in the big cities. Turns out, backwoods Mississippi was not immune. In a very big crowd in the middle of the afternoon in a wide-open field, one local walked up and put a large bullet from a loud gun into the heart of another. My friends were feet away, felt the heat of the flash, said the young man thudded to the ground, instantly lifeless. I was in the rear field, where the music was to resume, and my recollection is not of hearing the gunshot but the thunder of the dispersing crowd’s feet. The party emptied like the kid’s life left his body. It was there, then it was gone.

Otha’s picnics were nearby Buford’s, and while there’d never been a fight at Otha’s, I’d seen guns there too. Once, shooting night video, I focused on a glinting belt and didn’t realize until the later playback that it was a gun tucked in the small of someone’s back. But at Otha’s, unlike Buford’s, I never saw even a fistfight. I liked to believe this was due to Otha’s standing in the community; it’s what I told myself when I brought my three-year-old.

My passion also waned when, several years running, multiple documentary film crews descended on Otha’s. The picnic had grown by then, which meant Otha would make more money and probably sell more CDs. (For R. L. Burnside and Junior Kimbrough, popularity moved them from the area fields to the world’s stages, rewarding them with increased earnings in their later years.) The larger crowds were fine, the growth had been organic—but the film crews were different. They broke the mood. Their signs advised Otha’s longtime neighbors that they were now on a film set, and that felt like a violation of personal space—who the fuck were they, who’d never been here before, to dictate to the locals? The crews hit trouble when, on the dusty land, in the deep darkness, electricity was not readily available. There was no convenient place for their snack table. Then, the fife would pip from across the field somewhere; the fife performances occurred irregularly, and weren’t scheduled or announced. So the film crews stumbled and shoved and shouted to save their shoots, killing the feel they were trying to capture. Their refusal to listen was loud, their extension cords spread like kudzu vines.

But am I writing about myself? I’ve brought video cameras to places not usually documented. If I’ve done my work well, with pen or camera, I’ve invited the kind of growth I’m reacting against; am I disdaining my presence at many of the places in this book? Maybe. But I do think it’s possible to become enveloped in the audience, to minimize the intrusion; even a camera—which tends to objectify—can be used with tact. And I hope that has been my way, though I can’t know for certain.

At Otha’s, when he hit the fife, people would encircle him and the drummers, dancing and snaking with them. Many people took photographs. After the documentary crews, the locals with cameras seemed different, a sea of arms raised over the performers, lenses angled down and peering from all around. The whole tenor was off. The cloak of night was lifted and I felt exposed, angry that their presence had wrecked what had been a beautiful gathering. I wonder how Otha felt.

At one of those overexposed affairs—within five years the swarm departed and a local feel returned—I tried to buy some hooch from Otha. He kept it in his barn and over the course of the night I’d see him making forays there, returning to huddle close with one of his neighbors. Otha was known for his smooth white whiskey, and in the past I’d easily bought a jar. But this night, when the picnic was filled with so many strangers, he was trusting no one, the fear of being busted as old as the paths into the hills. I was glad when the picnics got smaller. Otha probably made less money, but I believe he enjoyed them more.

Liner notes to Everybody Hollerin’ Goat, 1998

A stretch of interstate. You are between two cities. It is night, and quiet, and each rural exit proposes the idea of what’s beyond, or suggests an emptiness far from your own thrumming world.

On a hot night in late August, less than an hour on the highway south of Memphis, you take an undistinguished exit onto roads so remote their names are not posted and drive less than fifteen minutes from the truckers and the travelers, passing maybe a dozen domiciles on a gravel road before you reach a sunken area off to the right and find yourself in Otha Turner’s backyard.

An old wooden barn leans. A white horse swishes its tail. Otha’s mule brays.

A fife and drum picnic. There may be five or fifty-five people milling about, blacks, whites, others. In 1970, fife and drum music was being played in Waverly Hall, Georgia, and in Otha’s area around Como, Mississippi. The tradition seems to have withered in rural Georgia, but at today’s picnics in Mississippi, when Otha Turner blows the dust from his cane with a flourish of trills, generations of Turners can, like the shamans, create spiritual music that divines the self from the self.

The side yard at Otha Turner’s during a picnic. From left, Lonnie Young, Chip Daniels (with microphone), Kenny Brown on porch with guitar, Otha Turner (overalls, back toward camera), Cedric Burnside on drums. (Courtesy of Yancey Allison)

Drums is a calling thing. The mighty pounding rings out through the dark Mississippi night, drums chasing the fife like dogs on a rabbit, and people step outside their homes and know Otha’s having a picnic.

Neighbors and friends materialize from the night, appearing first as the sound of crunching gravel, then as shadows on the dirt driveway, then fleshed beneath the electric lights that Otha has strung through his side yard. Beneath the lowest branches of giant trees, the yard has an embracing warmth, becomes a lair.

The picnics start on a Friday evening and end sometime on Sunday. On Friday, a couple goats will meet a hatchet, and the horse and the mule sigh with relief that they were not on this earth as goats to become three-dollar sandwiches at Otha’s picnics.

Friends have already started to collect, though it is just midday and the picnic hasn’t actually begun. Moonshines are compared. The goat must be barbecued, and with it a pig. A load of beers must be purchased for resale that night, some off-brand sodas, never enough ice.

Otha is ninety years old and powerful. His friends call him Gabe, like the archangel who blows the horn. His daughter Bernice has been playing since she was a child, and her teenaged sons—Andre, Rodney—and her nephew Aubrey (everyone calls him Bill)—they all blow the fife and beat the drums. But when it comes to family fife blowing, no one blows like granddaughter Sharde Thomas, who is eight and has been blowing the fife since she was five. She stands firm-footed like her granddad, holds the fife with authority, and blows “Shimmy She Wobble,” which also happens to be the first song Otha learned.

The community gathers for a fife and drum picnic. (Courtesy of Yancey Allison)

“I was about sixteen years old [making the year about 1923] when I started blowing the cane,” Otha told Luther Dickinson, his friend (and producer of this fine album). “It was an old man they called R. E. Williams, tall slim man. We would all come out of the field when it rained, too wet to pick cotton, and he’d be at his house blowing the ‘fice.’ I didn’t know what it was. I say, ‘Mr. R. E., how you make that? Will you make me one?’ He say, ‘Son, if you be a smart, industrious boy, listen to your mama and obey her, I’ll make you a fice.’ I wished it was tomorrow but it was about four weeks, he say, ‘Here your fice.’ I say, ‘I sure do thank you.’ He say, ‘You ain’t never gonna do nothing with it.’ I say, ‘But I’ll try.’ He say, ‘Well son, don’t nothing make a failing but a trying.’

“Everywhere I got a chance, I be trying to blow that cane. Mama say, ‘Put that dad-blamed cane down, I’m tired of it.’ Mr. R. E., he turned around blowing the cane and I just stood there watching him. And I learned how to blow it. I made my own songs.

“Then there’s a man called Will Edwards, he owned some drums. One day, we heard ’em, say, ‘Mama, I hear some drums.’ She say, ‘Y’all do your work, get ever’thing done so we come home tonight, I’ll give y’all a bath and carry you up there.’ We say, ‘Yes ma’am, yes ma’am.’

“We do our work, she give us a bath, and we go up there. There’s people standing around, old men down there playing drums, putting drums between their legs. They say, ‘What you looking at, son? Getting down ain’t it? You want to try it?’ I say, ‘Yes sir.’ He say, ‘Boy, don’t you bust my drum.’ I say, ‘No sir.’ I got that drum, mess around, be playing all around it. ‘Listen at him, Will, listen at him, that boy yonder playing that damn drum.’ After a while, he say, ‘All right, young man, you been raring for this, you got a job, you one of my players.’ And I started playing with other peoples. Guys found I could play the cane, they be hiring me, carrying me to different places.

“Then I say, ‘I’m gonna buy me some drums and start giving picnics.’ My kids say, ‘Daddy, you gonna do that? You got nobody to play.’ I say, ‘I’m gonna hire somebody to play.’ So I did, and my daughters, they kept a’watching me and wanting to try it. I say, ‘Don’t bust it!’

“So I was down at the field and I heard the drums at the house. I came back, asked my wife, ‘Who’s that messing with my drums.’ She say, ‘That’s your children.’ I say, ‘You mean to tell me that my children messing with my drums? Y’all go get the drums and bring it out. I wanna see can you play.’ They got them drums and played them drums. I say, ‘Well hooray for y’all!’ ”

In 1997, nearly all the fife and drum players in north Mississippi have learned from Otha Turner. Nearly all, in fact, are his kids, grandkids, some cousins, and lots of neighbors.

Every good session begins with Otha berating the drummers for playing too fast, or for playing too slow. He’s got to whip the fire into them. He assembles each lineup like a barbecue chef selecting spices. He knows the nuances between the older players and the younger, between each individual. They’ll beat the drums for a five- or twenty-minute stint, and everyone soloes and everyone plays together.

The players exchange instruments throughout the night, but performing at any one time there is usually one marching band bass drum, two snares, and a fife. Otha makes his fifes from cane the length of a bamboo segment and a half; they’re longer than a foot but not by much. He bores out the middle with a poker heated on coals, then, by sight, bores five fingerholes. The drums are shouldered with straps, allowing the players to snake slowly when playing. Otha’s fife is always kept handy in the back pocket of his overalls, at the ready like nunchucks.

The trance music begins as imperceptibly as a breeze, the sound of someone testing their instrument. Is it still there? It is still there. Another asks, Is mine still here? Mine is still here. Someone laughs loudly, buys another beer at Otha’s makeshift bar, yells, “Play that thing.”

Otha Turner made his own instruments from cane. He played smoking fife, 1998. (Courtesy of Bill Steber)

The crowd gathers, thicker suddenly, as people spill from the darkness. Otha begins to march and the drums follow. Not fast. Not slow. Snaking, people fall in behind them and beside them, arms raised overhead and swaying, hips shaking over the county line, forth and back, side to side, grinding and doing the do. Men hump the drums and women hump the drums. The crowd shouts, spurring the players to take them higher and further, spurring the dancers to shake with more abandon. A lady in her sixties throws herself in a push-up position and makes love to the earth.

The sound goes through us and reverberates off the trees and in the hollows all around. We are at the mouth of a cave. We are in Morocco with the Master Musicians of Jajouka, on a second line in New Orleans, the funereal spirit entwined with the life spirit. “The old people taught me and told me that that was African,” says Otha, “that way back in Africa, you played drums if somebody died. At the funeral, they would march behind the casket to the cemetery.”

Time blurs. The drum pounds. The fife hypnotizes, human breath through an ancient piece of wood. Serpentine goes the line behind Gabe, serpentine. “You makes a fice do what it do,” says Otha Turner, and he has the wisdom and the calluses that confirm this simple statement. “You know your cane with your fingers. You put that cane up and start to blowing, and you can put what you got through your mouth into that cane. The fice ain’t got but two whistles to it, high and low; you got to catch something yourself. Then know how to know it, then blow it. You got to be patient with it. You gots to know how to know it.”