The odds were long that Jerry Lee would be the last man standing from the Sun Records A-team. But after Johnny Cash died in 2003, no one else was left. Elvis Presley, Carl Perkins, Roy Orbison—the real wild child still reigned.

In 2005, I got word that “the Killer” was recording a new album in Memphis. I was friendly with his longtime associate and sometime manager J. W. Whitten. Jerry Lee is always a story, and when I asked about hanging around, J. W. welcomed me to the closed sessions, saying, “Just don’t get in the way.” At a Chicago signing for my Muddy Waters biography, Can’t Be Satisfied, an editor from Playboy introduced himself, said he was a fan, and invited me to write for the magazine. He liked the idea of a story on Jerry Lee.

I assumed that I’d sit down with Jerry Lee sometime during the latter half of 2005 when I was attending these intermittent recording sessions. J. W. never said no, but neither did he affirm. Gradually, as I watched Jerry Lee in action over an extended period, I realized the access I was getting was full of more truth than any interview would be. You make your story with what you get, and I got all I could ask for.

Playboy, February 2005

It’s a December night and despite the chill, Jerry Lee Lewis enters the Sam Phillips Recording Service in Memphis wearing flip-flops, green-and-blue plaid pajama bottoms, and a loose nylon jacket with a casino’s logo on the back. His band, along with the L.A. producer and engineer, have been waiting, and they gather around rock and roll’s original wild child, now seventy years old.

“You seen your mama lately?” Jerry Lee asks Kenny Lovelace, his guitar player of thirty-seven years.

“Was in Louisiana last week,” Kenny says.

“Tell your mama hello.”

Jerry’s in a good mood. Every night is different, and it can change from minute to minute, but this night, there’s a sharpness to his attitude that indicates all is right in his inscrutable world.

Some of the players are sipping beer, some grape soda. The L.A. producer, Jimmy Rip, tells Jerry that the song they cut at the previous session, a rare Jerry Lee original called “Ol’ Glory,” now has harmony vocals on it from country star Toby Keith. Jerry Lee’s in a storytelling mood, and the mention of one country star brings on a story about another. “You remember when old Waylon Jennings loaned me his fiddle?” Everyone nods and says, Yeah, yeah. “He knew my reputation on the piano and Waylon said, ‘I want it back in the same shape you’re getting it.’ ” Jerry Lee giggles a little, then says he told Waylon, “Or what?” There’s a beat and then everyone laughs, picturing these two music outlaws in a standoff.

But nothing gets past Jerry Lee. He sees everything that happens and senses everything that doesn’t. It’s a good story—told well—but it didn’t get the guffaws he expected, so he rolls on to another, one that conveys both humor and the sense of menacing hostility that always percolates below Jerry Lee’s skin. “You remember that record we cut in London?” Jerry asks Kenny, who played on The Session album. “Had all those people there and that drummer showed up, what’s his name?” The category’s too huge and no one suggests a name. “Played with that English band.” It’s slimmer now, but not by enough. Jerry Lee stammers, how to define him: “Ahh, ahh, played with the Beatles.”

“Ringo,” they all say. Oh that English band. “Yeah, Ringo. We kept him waiting there, and waiting. Not on purpose, but it just happened, until finally he couldn’t get in the room and announced, ‘Y’all can shove this record up your butts,’ and he walked out of there.” This time he gets the laughs. Ringo probably didn’t say y’all, but Jerry Lee sure did, cackling.

Half a century since the sun rose on rock and roll, Elvis and Buddy Holly are dead, Carl Perkins and Johnny Cash are dead. Little Richard is a caricature when he’s not a minister, and Chuck Berry’s going through the motions. Only Jerry Lee Lewis is still rocking.

The Killer is the unlikeliest survivor, but dying would have been the easy way out. In 1957, he created rock’s first great scandal—as an incestuous, cradle-robbing bigamist. He was twenty-two, and his wife Myra, his third wife, was thirteen. She was also his cousin. He tried to assuage the outcry by doubting the marriage’s validity, as he had never divorced his first wife. Record sales dried up. Not long past Myra’s sweet sixteen, their three-year-old son drowned in their backyard pool. A decade would pass before the public showed renewed warmth to him, and then only when he remade himself as a country singer. Tragedy stayed twinned to his triumphs; his firstborn from a previous marriage was killed in a single-car wreck in 1973.

Lewis is in the midst of divorcing his sixth wife. The onetime Miss Kerrie McCarver, however unhappy, must find relief in being the former and not the late Mrs. Jerry Lee Lewis. After nineteen years of marriage, she’s alive to tell the tale. Wife number five, the twenty-five-year-old Shawn Michelle Stevens, was not so lucky; she was found dead of an apparent drug overdose in the Nesbit, Mississippi, bedroom she’d shared with Jerry Lee for less than four months. Only a year prior, wife number four, Jaren Gunn, had also died—a swimming accident while awaiting a divorce decree. There’ve been fistfights, handguns, shotguns. On a tear in 1976, he accidentally shot his bass player in the chest (not fatally), flipped his car, and waved a handgun outside Graceland when Elvis wouldn’t come out and say hello; the next day, Elvis went to visit Jerry Lee, who was out, and wound up signing autographs on Jerry Lee’s lawn.

Jerry Lee Lewis drank more whiskey, took more pills, and had more car wrecks than most rock bands combined. He’s broken out of hospitals, fled Betty Ford Center treatment, and seen Hollywood make a cartoon of him. Newspapers have had his obituary on file at least since 1986, when he had emergency surgery for a ruptured stomach. Life, it seems, has clung to him, not he to life.

That’s unlike his peer, Elvis Presley. Elvis died like a wimp. Elvis was a girl. Wouldn’t fuck his beautiful wife? Got so fat he had to wear jumpsuits? Sang suck-ass songs like “The Impossible Dream”? And that wore him out at forty-two? “What the shit did Elvis do,” Jerry once said, “except take dope I couldn’t get ahold of?”

Survivors are the real sufferers.

But here he is, in Memphis, still recording and rocking, looking not half-bad and telling the warm-up stories of a rock and roll legend. Within thirty minutes of walking through the front door, Jerry Lee is down to business, running through tonight’s song, simultaneously simplifying it and making it more complex—Lewis-izing it. It’s a song called “Twilight,” by Robbie Robertson, a founding member of the Band, and the lyrics are about yearning for companionship while seeking the freedom of solitude. Jerry Lee really delivers on the refrain: “Don’t put me in a frame upon the mantel /’Fore memories turn dusty old and grey.”

Everyone’s familiar with the song. Now it’s a matter of the band all knowing it the same way, Lewis’s way, because he is one of music’s great interpreters—a “stylist,” he calls it. “There’s only ever been four stylists,” he’s famously stated. “Jerry Lee Lewis, Hank Williams, Al Jolson, and Jimmie Rodgers.” You can count the songs Lewis has written on one hand, but none of the hundreds of songs he’s recorded can be imitated. “Twilight” is about to metamorphose wildly.

Seated behind the piano, fooling with the progression of the song, he says to himself more than to anyone in particular, “This song’s got a lot of chords in it.” He begins the process with a sincere respect for the composer’s intentions. It’s just that Jerry’s ideas are better. “We got to play ’em. I don’t know ’em.”

The bass player pipes up. “I know ’em.”

“Show ’em to me.”

“Would you take offense?”

“C’mon.”

B. B. Cunningham strolls over to the piano. Cartoonist R. Crumb couldn’t have drawn B. B. better. He has a long, narrow face, its verticality emphasized by the ponytail that hangs to the middle of his back. His eyebrows can knit like a granny’s sewing needles, a worried look that appears when he smiles, which is often. B. B.’s father was a Sun recording artist, and in 1967, B. B.’s band the Hombres had a top-twenty hit with “Let It All Hang Out.” He first played with Jerry Lee in 1961, worked with George Clinton and Chuck Berry, and rejoined Jerry in 1997.

At the piano, B. B. runs down the chords. Jerry Lee watches, then does it himself. B. B. makes a correction near the end of the run. Jerry Lee gets it right, then states, flatly, “I don’t like it.”

“Look,” says B. B., “you can do it like this.” He runs through the chords with a variation.

“I don’t like that either.” Then Jerry’s talking just to B. B. He says, his voice low, “When I was thirteen years old, my piano teacher showed me a song. He was sitting right next to me like you are. When he got through with it, I said, ‘Wouldn’t it sound better like this?’ And reached in front of him and played my way. And the guy slapped me in the face.”

“I bet that got your attention.”

“It did more than that,” Jerry answered. “Since then I haven’t been able to learn anything from anybody. That was my last lesson. Get up and play your bass, B. B.” Jerry turns to the studio’s control room and says, “Maybe you should put one of those little things on there, ahh, ahh, what do you call them?”

“CDs,” says J. W. Whitten, Jerry Lee’s road manager, right-hand man, and mind reader.

“Yeah, play the CD.” He wants to hear the “Twilight” original again.

As B. B. returns to his position, he mutters, “I never thought I’d do that in my life, show Jerry Lee something on the piano.” (Actually, B. B. had done it once before, forty-two years ago, in 1962, at Jerry’s home when he was a guitar player in the band. He’d told him that to make a major chord into a minor chord on the piano, he had to change only one finger. Jerry Lee didn’t believe him, didn’t like the notion at all, and he chased B. B. out of the room and out the front door.)

The song’s rhythm evolves as Jerry begins playing. Producer Jimmy Rip, whose roots are in Texas and who evokes a beatnik cowboy, plays guitar. He says to the others, “He’s putting a shuffle in it.” The band feels their way and the song begins to sway. Jerry Lee’s singing, “It never crossed my mind / What’s right and what’s not,” and a yip and yodel creep into his voice. Rip and Kenny Lovelace glance at each other and laugh. On music stands before them, there’s a string of chords written out, but Jerry has simplified the song, each slew of chords summarized and expressed in the sweep of a single chord—not just that chord, but the space between that one and ones on either side of it. What’s not played is creating feeling, room for Jerry Lee Lewis to make “Twilight” his own.

“We got to come to some sort of collusion here about how we’re going to end,” says Jerry Lee. “It’s hard to end that song, it’s so pretty. “

Jimmy Rip answers with understated praise, “I love what you did to it.” Then he adds, “It’s a thrill to me giving you these songs and hearing what you give back. It’s always better.”

“If you hear something wrong,” Jerry Lee answers, “don’t hesitate to tell me so I can kill you.”

Jerry Lee Lewis was born to Elmo and Mamie Lewis on September 29, 1935, in Ferriday, Louisiana, a town that smells worse than shit. Ferriday is on the Mississippi River, across from Natchez, Mississippi, and there’s a paper plant there. The waft from a paper plant is all-encompassing. The stench is not something you just smell—you taste it, wear it, turn your face from but can’t escape it.

Tragedy first hit Jerry Lee’s life when he was three. His older brother, Elmo Jr., already displaying a strong musical talent at seven, was killed by a drunk driver. Around that same time, the Assembly of God church opened in Ferriday, and Elmo Lewis Sr. was drawn there, not just for consolation but also for the raucous music. He collected Jimmie Rodgers records and he liked to play guitar. The Assembly of God is a fundamentalist church that believes in visible manifestations of the Spirit, such as healing, visions, and everyday miracles. Their services capture the spirit of God through rapturous music, often expressed by fits in the aisles, by speaking in tongues, by shaking your nerves and rattling your brains.

Another early rock and roller was raised in a similar church. Elvis Presley got his stage moves from the Pentecostals he’d seen shaking on the pulpit. With their flailing and gyrations, neither Elvis nor Jerry Lee was doing anything he wouldn’t do on Sunday in front of his mother.

Like Elvis, whose twin died at birth, Jerry Lee was a surviving son. He was raised to be adulated. His parents risked their house to buy Jerry Lee an upright piano when he was ten. His mother, reveling in the sight of him, would run to his side, lift his arm, and call everyone close: “Look at the hairs!” she’d say to the assembled, and then to the golden-haired golden boy, “Jerry, every hair on your arm is perfect.” To which he would respond, “It certainly is.”

His style had already been formed. “The first song I learned to play was ‘Silent Night,’ and I played that rock and roll style,” he says. His influences at the time included Gene Autry, the singing cowboy whom he’d listened to from the alley behind the local movie theater (his family couldn’t afford the dime to enter), his parents’ hillbilly records, Hank Williams (since hearing Hank broadcast on The Louisiana Hayride in 1948, he’d been a committed fan), and the blues. Jerry Lee could hear the blues in Hank because he also heard it at Haney’s Big House in Ferriday, a juke joint for black field hands that Jerry Lee regularly snuck into, usually in company with his cousins Mickey Gilley, who became a country music star, and Jimmy Swaggart, later a famous television preacher, then an infamous one caught in several tangles with prostitutes.

At fourteen, Jerry Lee made his first public appearance, playing in the parking lot of Ferriday’s Ford dealership. “Drinking Wine Spo-Dee O’Dee” was a hit that year, and the audience responded to it that day; a hat was passed and it returned holding thirteen dollars. That was enough to convince Elmo to begin driving his son around the countryside, the piano in the back of a truck, stopping at crossroads, country stores, or anywhere a crowd might gather.

Soon Jerry Lee had his own car. “All the kin people would be out in the field working,” says his sister Frankie Jean, younger by nine years. “Mother would be pulling the sack, putting the cotton in it. Daddy would be right behind her, and I would be helping with Linda [baby sister and future performer Linda Gail Lewis]. He had a car, and he’d ride up—I have witnesses—he would ride up and down the gravel road along the river and he would scream, ‘Work you peasants, work! For I don’t have to work! For I’m wearing the white shirt! I am the great I am!’ ”

By the time Jerry Lee graduated from high school, he was twice married and a father. He entered his first marriage when he was sixteen, and twenty months later, prior to his divorce, he married Jane Mitchum, pregnant with his first child. With his wife and son cared for by his parents, Jerry Lee went to Waxahachie, Texas, for Bible college with plans to become a minister. He would absorb the fear of God by day, then sneak out to Dallas’s bright lights to see movies and ride the Tilt-A-Whirl at night. In assembly one day, his version of “My God Is Real” became a little too ungodly, and though the sounds of his church and his nightclub were often indistinguishable, this version was clearly over the line. Jerry Lee was expelled.

He sold vacuum cleaners and sewing machines, he played drums and piano with a local band, he auditioned in Shreveport for a country package tour in 1955. He tried his luck in Nashville, but Nashville was having none of the new sounds; Carl Perkins, another white singer who was mixing country and blues, had already been told by one corporate label rep there, “I like what you’re doing, young man, but I don’t know what you’re doing.”

That unidentifiable mix was much more suited to Memphis than to Nashville, which the Lewis family realized when they heard Johnny Cash and Carl Perkins in the summer of 1955, both on Memphis’s Sun Records, home also to Elvis Presley. To finance the trip to meet Sam Phillips, Elmo Lewis sold eggs—33 dozen—along the 350 miles north.

Working with Sam’s assistant Jack Clement, Jerry Lee cut “Crazy Arms,” his first Sun single. Though recently a country hit for Ray Price and a pop hit for the Andrews Sisters, “Crazy Arms” got infused with Jerry Lee’s personality, a country bounce that swings right to the juke house. His left hand played funky bass on the piano’s low keys, his right ran a lilting, wild-style melody. He quickly got good bookings, including a tour with Cash and Perkins.

In mid-March 1957, Sun released Jerry Lee’s second record. With Clement, the band had spent a lot of time working up a rollicking number called “It’ll Be Me.” It was a Clement original—he’d come up with it while sitting on the studio’s toilet, pondering reincarnation; the line, “If you see a turd in your toilet bowl, baby / It’ll be me and I’ll be staring at you” was changed before it was recorded, and became “If you find a lump in your sugar bowl.” The song’s feel was well-suited to Jerry Lee, but getting the romp just right was proving difficult. “I said, ‘Why don’t we come back to this later, Jerry? Let’s do something else for awhile,’ ” Clement recalls. “And ole J. W. Brown spoke up, Jerry Lee’s bass player, and said, ‘Hey, Jerry, do that song we’ve been doing on the road that everybody likes so much.’ I said, ‘Well let me go in there and turn on the machine.’ I hit play and record, sat down there, and they did ‘Whole Lot of Shakin’ Going On.’ No dry run, no nothin’. Blap! One take, there it was! Sprang forth full-blown from its mother’s womb. Then we went back to ‘It’ll Be Me.’ ”

It was the frenzy of “Whole Lot of Shakin’ ” that made Lewis a star. In a summer 1957 appearance on Steve Allen’s national TV show, Jerry Lee didn’t kowtow as Elvis had—standing awkwardly in a tuxedo and singing “Hound Dog” to a basset hound. Whipped up by his own performance, Jerry Lee hurled his piano bench offscreen, Steve Allen threw it back, and “Whole Lot of Shakin’ ” shot from regional hit to number one country and number two pop (unable to shake Debbie Reynolds’s “Tammy” from the top spot). Jerry’s next child was named Steve Allen Lewis.

A month after the “Twilight” session when B. B. Cunningham had escaped without getting slapped, Jerry Lee performs at a Christmastime benefit concert in Memphis. Hometown gigs are rare, especially in smaller venues like this club. His touring has picked up since his divorce proceedings began a couple years back. He can command sizable fees for an appearance; he and the band even flew to Switzerland for a single performance. In a Biloxi casino, he set a recent record. Tonight, he’s closing the show, and the audience stays late to see him.

Numerous acts have preceded him, and a weariness has set in, but when he’s announced, the audience greets him with a standing ovation. His crowds trend toward older, but there’s always younger people making sure their lives will include seeing this legendary performer. Entering from the side, he does a fanny-shaking shimmy to great applause. He’s wearing a leather waistcoat that he doesn’t remove before sitting at the piano. But he’s got nothing to hide—he’s slender and looking fit. He kicks off with “Roll Over Beethoven” and that bleeds into Hank Williams’s “You Win Again.” The tempo changes, the feel, the emphasis—but it’s still distinctly Jerry Lee. His voice is full of power this night, and he performs both “Great Balls of Fire” and “Whole Lot of Shakin’.” He’s conjuring the spirit from within, from the place where good meets bad and right meets wrong and the forces push and they pull and the tension is exhilarating so that you find yourself unable to stand still and unable to move—shake, baby, shake—and part of you feels like it might explode—easy now—until there’s a moment of liberation and what’s happening on stage is happening in the audience and no one can say who is leading because everyone together is joining everyone else in some kind of new freedom.

For the audience, it’s thrills and chills to follow these nonstop twists, but on stage, it’s a workout. “I always keep my eyes right on his hands,” says Robert Hall, Jerry’s drummer since 1996. “There’s twenty regular songs he draws on, and sixty or eighty backups that could come in at any time, and a solid forty that I’ve never even heard. We still get a new one every now and then.”

“He pushes you farther than you think you are willing to go,” says bassist B. B. Cunningham, who is so comfortable rolling with the punches that he once tuned Chuck Berry’s guitar to the A of a hotel telephone’s dial tone. “We try to recognize what key he’s in, then pick up what he’s doing. One night in Vegas he started playing something that even Kenny couldn’t follow, and he’s been with him for thirty-seven years. Nobody played anything, we just let him play. And all of a sudden he stopped, leaned into the microphone, ‘Are you boys going to jump in with me or just take my money?’

“He has no set list, and I think the reason he does that is it gives him the freedom to do what he feels like doing. And it’s part of the mystique: What’s going to happen tonight?”

It was a hot August day in 1957, before air-conditioning was common, when Sam Phillips gathered Jerry Lee and his band in the breezeless Sun Studio to record a follow-up to “Whole Lot of Shakin’.” Sam’s recent Carl Perkins and Johnny Cash singles hadn’t hit, and he’d sold Elvis to RCA, so Sam needed “Great Balls of Fire” just right. The song was perfect for Jerry Lee, built around the tension between sexual release and religious exaltation—two of Jerry Lee’s favorite pursuits (others include cars, motorcycles, tobacco pipes, and boots).

Sam Phillips was a master of production psychology. (Had he not gone into records, he’d have made a helluva preacher, lawyer, or therapist.) As a warm-up for the song, he and Jerry Lee were discussing theology; Jack Clement hit the record button.

“H-E-L-L!” the Killer exclaims, and he claps his hand on the piano for emphasis. “It says, ‘Make merry with the joy of God only.’ But when it comes to worldly music, rock ’n’ roll, anything like that, you have done brought yourself into the world, and you’re in the world, and … you’re still a sinner …”

“All right,” responds Sam, maintaining a cool in the heat of Jerry Lee’s passion. “Now look, Jerry. Religious conviction doesn’t mean anything resembling extremism … Jesus Christ came into this world; He tolerated man. He didn’t preach from one pulpit, He went around and did good … When you think that you can’t do good if you’re a rock ’n’ roll exponent—”

“You can do good, Mr. Phillips, don’t get me wrong—”

“When I say do good—”

“You can have a kind heart! You can help people—”

Sam stunned him: “You can save souls!”

“No! No! No! No! How can the Devil save souls? What are you talkin’ about? Man, I got the Devil in me; if I didn’t I’d be a Christian!”

A few moments later, riled and primed by the record producer, this musician achieved one of the artistic high points of his life. With apocalyptic imagery, lascivious delivery, and unbridled energy, Jerry Lee Lewis cut “Great Balls of Fire” as if announcing the End of Days.

The song was featured in a Hollywood teen-exploitation film called Jamboree; it was the movie’s only song to feature an electric bass player—Jerry Lee’s first cousin J. W. Brown.

Cousin Brown—his mom and Jerry Lee’s dad were siblings—was an electrician who opened his Memphis home to Jerry Lee, his second wife, and his young namesake. When the dads were on the road, Brown’s preteen daughter, Myra, saw that Jerry Lee Jr.’s mama was cavorting with other men. She already had a crush on her exciting older cousin, and after his divorce, the cousins eloped in December 1957. Myra had turned thirteen. Singing to her, perhaps, his next hits were “Breathless” and the forward-looking “High School Confidential.”

While their love was blooming, the relationship between the entertainer and the press was about to wither. Reviewers, critics, and writers had helped launch his career, but with the revelations of his wife’s age, their blood relationship, and his past marriages, the press took to assaulting his character. Jerry Lee came to see all journalists as murderous, a stance that he maintains to this day: He has no interest in mixing with the press, no trust that they’ll do anything but create bloodthirsty headlines.

“He’s a man of a great, contrite heart who’s just maybe messed himself up from time to time,” Sam Phillips said a quarter of a century ago. “It’s a shame he doesn’t have anyone to direct his talent—he is one of this century’s great, great talents. But he feels a lonesomeness in his talent, extreme lonesomeness, for somebody to be strong around him.”

Even at his lowest point, he still had the demeanor of an angry god. When touring in the 1960s, playing state fairs and dive bars before his Nashville comeback, he got an engagement in a Miami nightclub following a two-week stint by Conway Twitty, who’d known Jerry Lee since they were both at Sun. Twitty warned the club owner of Jerry Lee’s pounding piano style, so the owner bought a beaten upright for the gig. “Jerry showed up the afternoon he was supposed to open,” Twitty recalled, “took one look at the piano and kicked it off the stage onto the floor. He kicked it all the way out of the building, across the parking lot, and into this lake. Then came back in, blew cigar smoke in this mobster’s face, and said, ‘Now get me a goddamn piano.’ ” He got his piano.

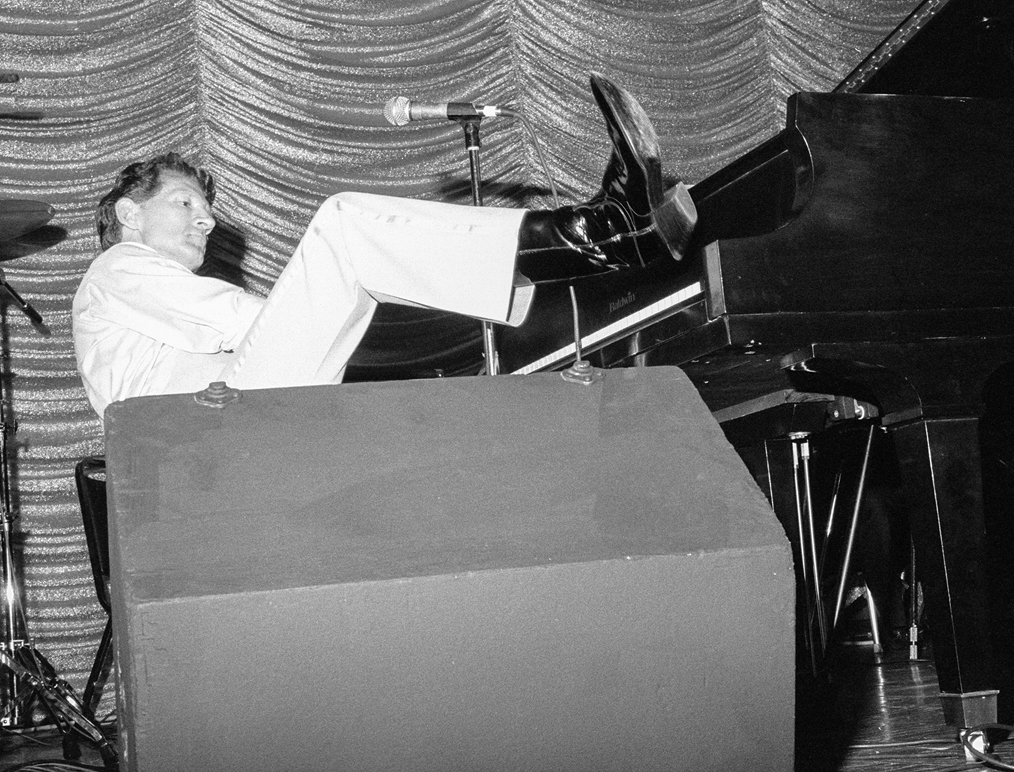

Jerry Lee Lewis, 1995. “At a show not long ago, someone passed a request to him on a cocktail napkin; without a glance, he blew his nose on it.” (Courtesy of Trey Harrison)

There’s another recording session for the new album. Jimmy Rip has flown to Memphis from Los Angeles, but there’s no band this night. They’ll record three songs, piano and vocals only, and add guest vocals and backing tracks later: “What’s Made Milwaukee Famous (Has Made a Loser Out of Me)” will get a visit from Rod Stewart; Jerry Lee’s first ever recording of Hank Williams’s “Lost Highway” will be bolstered by Delaney Bramlett’s raspy vocal; and “Miss the Mississippi and You,” a yodeling classic by Jimmie Rodgers that won’t make the album.

He’s brought to the studio by his daughter Phoebe. She drove. Used to be, he’d drive her to grade school in his Rolls-Royce—until one day he flipped that car (walking away unscathed) shortly after dropping her off. Now Phoebe’s in her early forties and, since her father’s divorce proceedings, she has stepped up to help manage his affairs.

Phoebe has long blonde hair and her father’s spirit. She speaks with a deep Mississippi twang and smokes a corncob pipe, and she’s excited about this new album. “I couldn’t believe I was hearing Led Zeppelin’s ‘Rock and Roll’ cranked up full volume blaring out of my dad’s bedroom. He was learning the song. And of course he cut it totally different.”

Rip is pleased to have Phoebe at the session. Jerry Lee is not allowed to go anywhere alone. He drinks hardly any alcohol these days, and pills, reefer, and all drugs except those prescribed by his physician are out of his life. (At a recent doctor’s visit following a teeth transplant, Jerry Lee was pronounced in perfect health. The new teeth have not affected the peculiar wet slur that has always made his speech an effort to understand.) It may be whatever he’s taking to keep him from taking anything else, it may be a life of being doted upon, or it’s that Jerry Lee feels like he owns every damn place he finds himself—but Jerry Lee needs looking after. In a hotel not long ago, he wound up alone in his room. “Hey!” he shouted, because he needed something, but there was no answer, so he shouted “Hey!” louder, and then again and again, louder and louder, until he left his room in his socks and underwear, wandering the hotel hallway, directionless, shouting, “Hey!”

Jerry’s out at the piano noodling around and without pause or introduction, he breaks into “What’s Made Milwaukee Famous.” The engineer is Roland Janes, who, besides being the house engineer at the Sam Phillips Recording Service, was Jerry Lee’s guitar player from the glory days—Roland can read Jerry and he’s missed nothing—had the tape rolling in plenty of time.

Jerry moves on to the Hank song. He’s reading the lyrics off the piano, but he’s singing with fervor. (He was reading the lyrics when he recorded “Great Balls of Fire” at Sun.) “I’m a rolling stone, all alone and lost / For a life of sin, I have paid the cost …”

“I tried to find songs that pertain to his life, things that will allow him to be really emotional and expressive and tell the story of what he’s gone through,” says Rip.

Jerry has switched from rehearsing to recording without telling anyone, and even Roland misses the turn. “Hold it,” his old friend says into the talkback, “wasn’t rolling.”

“Aww now,” says Jerry Lee. “You ruffled my feathers. Let me go get my pistol.”

A visitor in the control booth gasps and says, “Oh no, not the pistol.” After waiting a couple beats, as if he could hear the fear, Jerry adds, “Only a joke. I ain’t got a pistol.”

“Boys don’t start that stupid rambling ’round,” he’s singing, his back straight, his face stern beneath eyeglasses, beady eyes focused on the page. His profile is sharp, like a hawk’s. The piano hides his flip-flops and pajamas. Jerry Lee could be a preacher alongside his cousin Swaggart. “Take my advice …”

Jimmy Rip steps out to the studio between takes, says, “One more?”

“One? At least ten more.”

“I think one more will be enough.”

“Too bad you don’t know me,” says Jerry Lee, “as well as you think you know me.” The honesty is startling, said without pretense. With each take, he’s peeled at the song, to simplify and complicate, to reveal more of his terrifying, terrified soul.

“If you let me get this down right, you’ll have a million seller on your hands. Twenty or thirty more takes.” Jerry’s pushing, but the producer resists. Jimmy explains that from the three keeper takes he can build a single solid one on the computer. “Play it back then,” Jerry snaps. He’s willing to listen to what they’ve got, to be happy if Jimmy’s happy, but he really doesn’t feel like he’s hit his lick yet. “Don’t cover up my mistakes with the band,” he protests. “Let me get it right. He writes everything you do in the Book of Life, and He’ll hear it. Dim the lights.”

Jimmy says, “Lighting is everything.”

Jerry corrects him. “Naw, it’s a little part of it, but it means a lot.” He begins one more take—it opens completely differently from all the others. “One more,” he says again, but no longer means it, having heard what’s there and realizing he’s done a good job.

After the session, there’s small talk in the control room. Jerry’s bought his seventeen-year-old son, Lee, a big SUV and he laughs when he complains about the cost of the insurance. Phoebe laughs, then says her dad recently set his Harley-Davidson inside the living room of his ranch, where he can admire it. After several days of looking, he could resist no longer. He opened the sliding glass door so the exhaust wouldn’t kill him, mounted the beast, kicked—and unleashed mayhem. The machine roared throughout the house, the dog went crazy barking, and the fumes set off the smoke alarm.

Jerry Lee’s Nesbit home is a sprawling ranch built on thirty acres with its own lake. It’s got six bedrooms and six bathrooms, and plenty of living space. He’s lived there since 1973 and it suits him just fine. Phoebe occupies one of the suites, and their longtime helper Carolyn is often around. She cooks like Jerry’s mama—Phoebe’s given her the family recipes. He eats only one real meal a day, dinner around eight, but he’ll snack. A night owl, he’s got a suite in the back where he sleeps, bathes, and watches a big-screen TV—big, like IMAX for the home. His collections are on display there—model cars, tobacco pipes (his many boots are kept in his closet)—and so are his prizes and awards, his Grammy (not bestowed for his hits, but for Best Spoken Word or Non-Musical Recording, 1986, an album entitled Interviews from the Class of ’55 Recording Sessions), and some of the gifts he’s been given. “Little bitty things mean the most to him,” says J. W. Whitten, the road manager. “A friend will get him something and he’ll cherish it.”

Studio talk turns to Gunsmoke, an indication that the evening is going great. Gunsmoke is Jerry Lee’s favorite subject in the world. He loves television, and westerns are his favorite. Of all the westerns, he loves Gunsmoke. Of the two kinds of Gunsmoke, he prefers the episodes with Chester, the Dennis Weaver character, over the ones with Festus, his replacement. When asked why he likes Gunsmoke so much, Jerry Lee answers, “Because it’s unique, perfect, and great. I got tapes going back to 1954—Kitty was beautiful. Matt Dillon is my hero.” He freely admits that he cried when Harry Dean Stanton’s character died in the show.

Jerry Lee is legendary as a rock and roller, so it’s often forgotten that when he came to Sun, he was playing George Jones and Ray Price songs, a Carter Family number, and Jimmie Rodgers. And it was to country he turned in 1967, a decade after his meteor burned up. He signed a deal in Nashville, made classic honky-tonk comfortable in the modern era with “Another Place, Another Time,” and began a string of country hits—many in the top three, and more than several that crossed over to pop—that ran all the way through the 1970s and included “What’s Made Milwaukee Famous,” “She Still Comes Around (To Love What’s Left of Me),” “She Even Woke Me Up to Say Goodbye,” “Would You Take Another Chance on Me,” “Middle Age Crazy,” and “Thirty Nine and Holding.”

The run ended in the late 1970s, when the individualism Jerry brought to his late-1960s hits was no longer appreciated. By then, the label was shipping syrupy, finished tapes to Memphis onto which Jerry Lee simply added his part, often only a vocal. He’d come to the studio—the same one where he’s cutting this new album—so rankled that Sam’s son Knox would load blank tape onto which Jerry Lee would pour out his wrath and anger before finally he was weary enough to give Nashville the saccharine they wanted. Those tapes—those documents of rage and sorrow—remain sealed in a dark vault.

He married Kerrie McCarver in the mid-1980s, and initially they ran a nice little Jerry Lee Lewis cottage industry. His fan club was thriving, she opened his home to tours, and she took over management of his career. But storm clouds appeared. Little Richard, with whom Jerry Lee has always gotten along famously, reported to several entourage members, “That fat white girl called me a nigger to my face.” After her first European tour, contracts reportedly began having “no-Kerrie” clauses in them; she was not welcome back. “It was a relief for us,” says one entourage member.

In 1985, Jerry Lee was fifty and soon to be a daddy. “I want my unborn son to have a drug-free daddy,” he said at the Betty Ford Clinic, but two days after checking in, he checked out. “Patients are supposed to clean bathrooms, take out garbage, sweep floors, and pick up after people. Hey, that may be fine for Suzie Homemaker, but it ain’t my style.” He fled.

The new family moved to Ireland during a protracted battle with the IRS. But over time, the partnerships—the marriage and the business—soured, until Jerry Lee basically quit performing. Kerrie was evicted from the house by a judge’s decree, but the divorce, with all its attendant court appearances, lawyers, and gag orders has been ongoing since summer 2003. (The marriage ended in 2005 after 21 years.)

Upon arriving at Phillips Recording Service, it’s immediately evident that this last session for the album—tentatively titled The Pilgrim, or possibly Old Glory (and ultimately Last Man Standing)—is going to be different. There’s a tour bus parked out front, and movie lights are glowing. The lobby, usually so quiet the echo of the 1950s can be heard, is a film crew’s staging area, with a full spread of snacks and coolers of cold drinks. “When I started doing this record, it was so low-key,” says Jimmy Rip. “For this to be the end, it’s wild. A studio full of people—I don’t know who anyone is.”

A couple weeks earlier, Jerry Lee had been in Los Angeles to tape a Willie Nelson & Friends TV special alongside Merle Haggard, Keith Richards, and Toby Keith—all guests (Nelson included) on Jerry Lee’s new album. (Other guests include Mick Jagger, Eric Clapton, Jimmy Page, Buddy Guy, and Bruce Springsteen.) Jerry Lee was slated to close the show, in a duet with Kid Rock. If the pairing was unexpected, it was spiritually right, and the music would follow.

Two days before the May taping, Jerry Lee had never heard of Kid Rock. Phoebe looked him up on the Internet and the first picture they saw was Kid Rock standing atop a grand piano. “I like him already,” Jerry Lee said.

They were slated to play “Whole Lot of Shakin’,” and there was the idea of working up a take of the Stones’ “Honky Tonk Woman.” Jerry had practiced the song, but under the eyes of five cameras, seventy crew people, and the song’s co-writer—Keith Richards—Jerry couldn’t get it. The idea was scrapped. But Kid Rock and the Ferriday Kid behaved like reunited father and son. Rock never left the Killer’s side, and Jerry was digging him right back.

And thus this last session: That’s Kid Rock’s bus out front, itineraries having been aligned to record “Honky Tonk Woman.” The film crew is from DreamWorks Nashville, the label releasing the new record. The label head is James Stroud, who played drums in Jerry Lee’s band in the early 1970s. He’s playing on tonight’s session. Before the evening’s out, he’ll have had so much fun that he declares he’s making this record the company’s number one priority.

The engineer is playing the Stones’ version of the song, and the backup singers—who sang on Elvis’s “Suspicious Minds”—are working up their “gimme gimme” vocal track—not realizing that Jerry Lee might change the song a bit, a lot—entirely.

Kid Rock is wearing black: jeans, T-shirt, hat. His cigar is brown, which matches his snakeskin boots. His gold cross is bigger than his large plastic cup of whiskey and cola. Waiting for Jerry Lee, he’s inviting people onto his bus, where the Detroit Pistons are playing on a TV the size of—the side of a bus. His people are easy to spot—they’re burly as bears and they’ve got electric coils coming out of their ears and going down their backs. They’re either looking for assassins or listening to the Pistons game (they’re up at the half).

As his car approaches, Jerry Lee’s jaw drops. He steps out, says, “I gotta go comb my hair. Looks like we got an audience already.” Road manager J. W. Whitten, who’s driven him, suggests he use the bus. Kid Rock bows to show his hospitality. “They got one inside,” Jerry Lee says. “I been paying for it for twenty-nine years.” He’s not wearing pajamas tonight but rather crisp black jeans and a black shirt with gold trim that will flash in his video—but he’s still got on the flip-flops. His skin looks pastier than usual, and he’s sucking on a tobacco pipe. “I like that crease in your pants,” Kid Rock says with genuine admiration. “That’s old-school. I ain’t coming near you, you’ll cut me.”

As Jerry Lee glides through the track, his “Honky Tonk Woman” sounds appropriate for a honky-tonk. “I’m bad about changing up songs,” Jerry Lee says. “But this I want to keep about right. The guy who wrote it is a personal friend of mine, and he gets mad if you change it.”

“Let’s change it then,” Kid Rock says, an eager student in the Jerry Lee school. He suggests starting it as a slow gospel thing.

He is full of ideas—he inserts a break for the drummer, then for the whole band. He modifies Jerry Lee’s verse again, telling the multiracial background trio, “Hit on the upbeat,” slapping time on his knee. They run the song down. Jerry Lee says, “Well, you might have an idea there.” The producer agrees—these pros are ready to recognize positive input. “It’s good,” Rip says. Kid Rock answers: “It’s rock and roll.” And Jerry Lee, out of the side of his mouth and a bit under his breath, says into his mic, his voice rising like a question, “That’s rock and roll?” It’s wry and contentious, just this side of snide, and there’s a weighty pause after he says it, everyone in the room reflecting on what’s just happened. It’s not a put-down, it’s just something that the granddaddy of rock and roll is allowed to say, and it’s laden with meaning and humor.

After the session, the Killer tells the Kid, “Don’t let nobody change your style,” and the Kid replies, “I won’t.”

There’s lots of jubilant photo taking, and Kid’s standing next to Jerry Lee when he says, “Show me something on the piano.” The two share the bench and Jerry Lee pulls out Fats Domino’s “Walking to New Orleans.” But Kid’s really too excited to pay attention, and they wind up doing a duet of Hank Williams’s “Lovesick Blues.” The talk leads to Hank, then to Louisiana. “Did you ever live near a paper plant?” the Killer asks. “Auto plants,” says Kid. “Detroit.” “Man, you should live near a paper plant. It stinks.” It’s been nearly half a century since Jerry Lee lived downwind of Natchez, but there’s a lot he ain’t forgot.

At eight P.M. on a summer’s night, the band congregates in a Memphis hotel parking lot. A luxury bus will cart us all to Nashville, where Jerry Lee is closing a star-studded night hosted by Marty Stuart at the historic Ryman Auditorium—the mother church of country music. Jerry’s due to play at one in the morning. The last one to arrive, he boards and heads directly to his suite in the back, son Lee in tow. He turns on the big-screen TV, settles onto the comfortable sofa, and sits slack-jawed, rapt with a three-quarter smile for the next three or so hours. It doesn’t matter that Ronald Reagan’s funeral is the only show on; television—sitcoms, a hemorrhoid commercial, Moses coming down from the mountain—makes him oblivious to the world, and happy.

This performance is part of country music’s Fan Fair, an annual event at which fans from all over the world can meet their favorite stars. Jerry Lee’s never been totally comfortable with fans. At a show not long ago, someone passed a request to him on a cocktail napkin; without a glance, he blew his nose on it. When his bus pulls into the alley behind the Ryman—the alley that Hank Williams used to cross during the Grand Ole Opry to get a drink at Tootsie’s Orchid Lounge—fans swarm the vehicle. No one disembarks, but one elderly gentleman is let on. It’s Jerry Lee’s barber, and they talk about old times while Jerry gets a trim.

Outside, fans wait patiently and expectantly. Nashville is weird—there are no staggering drunks, no rowdy banter, just an orderly combination of grandmas, granddads, and young supple granddaughters. A ponytailed man in his sixties is holding a stack of albums (not CDs) that he’s dreaming of getting autographed. Many people have markers and pens at the ready, pick guards pulled off their guitars, autograph books open to a blank page. “Should we just get a picture of the bus?” asks one woman, tired of waiting. “Whose bus is that?” asks another. When she’s told, she repeats his name and stares, sounding surprised that he’s still living.

At one forty-five, Jerry Lee disembarks and heads to the stage. Passing through the fans, he’s anything but fair, greeting the peasants cursorily, making no real contact; he seems repulsed by the idea of touching something of theirs. He’s there to perform on the stage, not anywhere else. Strolling directly to the piano—there is great applause—he begins to play “Roll Over Beethoven.” He sits three-quarters cocked to the audience. More than half-cocked, fully loaded, bangin’ ’em out.

Jerry Lee’s hands pound out a fury. Sometimes they seem barely to rise off the piano, and other times he’s all asses and elbows, his arms flailing like a roller coaster ride. The piano is an extension of his own being, and he commands it. He pounds and strikes the keys with the seeming randomness of a child, and he makes beautiful music. He’s been known to stomp on keys with the heels of his boots, to pound them with his fists, to place his butt squarely on the ivories—and always the piano sounds perfect. He’s declared that he can stare at the piano and make it play.

Jerry Lee Lewis, 1982. (Courtesy of Pat Rainer)

Within seconds of the thirty-minute set’s last notes, Jerry Lee is back on the bus, settled on the rear suite’s sofa, mouth agape, eyes looking at the TV. A couple hours later, five in the morning, rolling down the highway, I walk back to the bathroom on the bus. It’s the last door on the left, just before his suite. He’s reclining on the sofa, framed by the doorway, his hair newly trimmed, the TV uncomfortably loud. He’s slouched, his feet planted firmly on the floor, ready to kick anyone who dares cross the threshold, who mistakes his door for the bathroom door and tries to piss on him. He looks up as I near and glares—his eyes burning through an unhealthful pallor, but burning. His skin shines like wax, but the meaning in his look is real. He glares like the devil.

Jerry Lee’s glare is as intimate and arbitrary as Elvis Presley’s gifts of Cadillacs. It’s a way to retain control of the moment. When Elvis slurred that he was buying you—a stranger, a friend—a Cadillac, he was purchasing not just the moment, but his control of you. You say no, you piss him off and the relationship is over; you say yes, you’ve lost your power of independence. So it is with Jerry Lee’s glare. Respond to the glower with a challenge—“Yeah, what do you want to do about it?”—and get thrown off the bus; tuck tail and meekly go about your business, you prove yourself a candy ass. In a business of manipulation, the glare, the Caddy, these are masterful moves that make so much middle ground inaccessible. I fumble with the door.

The TV in the back of the bus is so loud—even over the noise of a tour bus barreling seventy miles per hour on the expressway—and the day has stretched so long that someone finally slides the suite door shut. Jerry Lee—rapt at the altar of TV—doesn’t notice. Bandmembers climb into bunks, an hour of shut-eye before they can go home and sleep.

The sky is pale purple, becoming the white of day, and the bus is on city streets when there’s an angry banging and someone shouts, “Open this door.” For a minute, I am seeing the Twilight Zone image of the gremlin outside the airplane window who has hung on through the whole flight. The banging continues; it’s from the back of the bus—someone’s locked in the bathroom?—and as we get oriented from half sleep, we realize it’s Jerry Lee. “I want this door open right now!” He’s saying it with such force, the door itself must cower before him. Blam! Blam! Blam! B. B. Cunningham hustles down the aisle, sees it’s a sliding door, feels everywhere trying to find a handle for it, takes a hit as the assault on the door happens right by his head. “Somebody open this door!” There’s panic in Jerry Lee’s voice, like he’s drowning near shore, each pounding blow as strong as a victim’s flailing. B. B.’s bent at the waist, trying to get his fingernails wedged between the metal frame and the side of the door to rip it open.

Blam! Blam! Blam! “Somebody open this door right now.” There’s a syncopation to the banging and the shouting—it’s not something you’d dance to, but it sure gets your attention. The bus driver hears the commotion and yells to the back, “It’s pneumatic.” Bang! Bang! “It runs on air,” he yells, “push the button.” There’s a crowd at the door when the message reaches the back: “Push the big black button to the right of the door.” Like Batman, like Austin Powers, like Indiana Jones—the door disappears inside the wall and reveals Jerry Lee Lewis, an everyday miracle, stunned but with an aura of fire burning like a voodoo candle, a voodoo bonfire. He is silent, he speaks, he steps out of the room, back in. What he does and says is nothing to how he appears: a ball of fire, of pent-up rage. He’s a warm front of vulnerability, a cold front of anger and mistrust, the thundering fury that is Jerry Lee Lewis. Life is hell, and Jerry Lee is still paying.