Jerry McGill is the legendary outlaw of the Memphis underground, a gun-toting cowboy hero in black, the rebel who does wrong in the name of right. He’s the ugly woman who showed up at a Mud Boy and the Neutrons gig and uttered the line, “Known felons in drag,” which became the title of their first album. I’d sought information on McGill when writing It Came from Memphis and again when making the documentary from Bill Eggleston’s 1970s vérité footage, Stranded in Canton, but the only evidence of his existence was the occasional collect call from a penitentiary to Roland Janes, the house producer at the Sam Phillips Recording Service and former Sun Records guitarist. Roland didn’t mind all that much hearing from Jerry, but he didn’t love it either, because it could be a short step from a phone call to your front door. And McGill was, for many people, better a legend than a bodily presence.

For me, finding McGill was a reminder to be careful what you wish for. He remained part of my life until he died, always alerting me in subtle ways that he could find me when he wanted to. There were signs I should have seen, like the fact that when he finally surfaced in 2010, Mary Lindsay Dickinson did not want him to know even in which state she and Jim lived. There were many unpleasant days when making Very Extremely Dangerous, when the vérité footage of Jerry’s ugliness was overwhelming. For this new movie in which we followed him for about ten weeks—fresh out of prison, newly connected to his old girlfriend, and suddenly diagnosed with lung cancer—we had to make Jerry’s character at least somewhat palatable, and we’d enter the edit room saying, Time to chisel off some more hate. But there were also some experiences shooting it that were so full of humanity, my heart could barely take it—more than once he gave advice to little kids, drawing from his mistakes to improve the lives of those he didn’t know. The humanity and the venom—an outlaw’s realm.

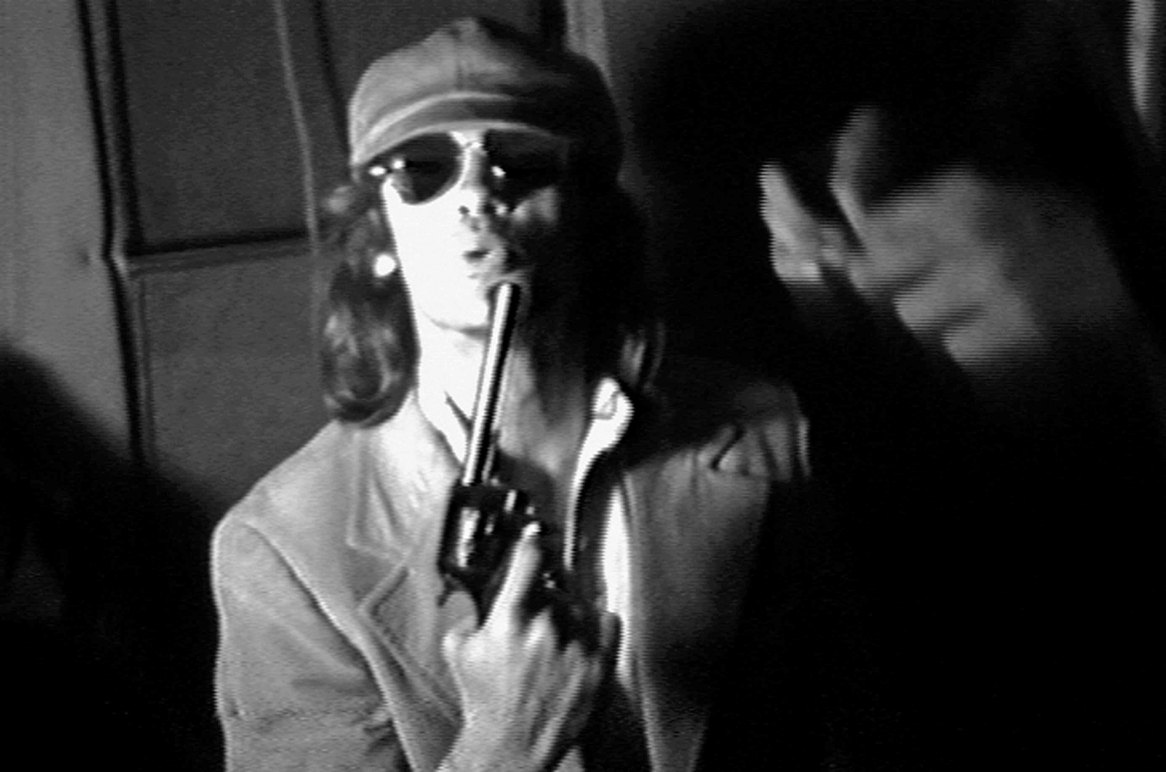

Jerry McGill, from William Eggleston’s Stranded in Canton. (Courtesy of William Eggleston)

We made this movie knowing only that McGill was a compelling character and trusting that if we stayed with him, we’d find a story. A fictional narrative filmmaker writes the story, then shoots the pieces and edits them together—easy peasy. Documentaries are much more challenging—the footage is all there, what’s the narrative? When this film’s termination sideswiped us, we found ourselves in the edit room, reviewing the material and asking, What’s the story? It is, in a way, the most exciting kind of filmmaking.

I’ve maintained contact with Jerry’s then girlfriend, Joyce. She’s a lot more stable since his demise, and she doesn’t have his temper. Or his guns.

Liner notes to Very Extremely Dangerous, 2014

I made a mistake in my first conversation with Jerry McGill that would (mis)shape our enduring relationship: I gave him my home address. Prior to this first spring 2010 phone call, I’d searched the Florida prison records for information about him, seeking both “Jerry McGill” and “Jerry Cole” (his birth name). Later I’d learn he was serving under the alias Billy Thurman. The first time McGill heard his real name during this prison stay was on his way out. As McGill, just discharged, approached the sunlight, a beefy Florida prison screw pushed open the big office door and called out, “Thurman!” McGill looked up and answered subserviently, as prison had taught him. The screw said, “Who is Jerry McGill?” McGill, smelling freedom, did not miss a beat. “That’s my BMI name, that’s the name I write songs under.” And he was free again.

Jerry McGill first came to my attention through Jim Dickinson, the Memphis record producer, Rolling Stones accompanist, and Big Star producer. Dickinson told me about the 1973 portable video footage that photographer William Eggleston shot, Stranded in Canton. Eggleston’s movie is stolen—and his life almost taken—by Jerry McGill, behaving at his most out-there (or so one would have thought, until we shot our documentary). The gun in his hand held to another man’s temple, McGill turns to Eggleston’s camera, steely behind dark shades in a dark room, and says, “I don’t care nothing ’bout that.” Talking to the camera, about the camera.

After the ensuing four decades, I learned, his sense of bravado had faded not at all.

Jerry McGill was Memphis’s homegrown Lash LaRue, our own personal outlaw. McGill traded Lash’s black whip for a .44 Magnum, kept the black hat, kited checks, attempted murder, robbed a liquor store and some banks, and stayed on the lam.

Rock and roll led him to his life of crime. He cut the only record he’d ever release at nineteen for Sam Phillips’s Sun Records in 1959. He’d play the nightclub stage, then after the spotlight’s glare, he’d meet the criminals and make a new kind of record: a sheaf of Memphis arrests and more serious issues with the Feds.

He always loved music, and during most of his thirteen years running from federal agents (the armed robbery charge), McGill was Waylon Jennings’s road manager, mostly under the name Curtis Buck. That’s how he’s acknowledged on Waylon’s albums—as rhythm guitarist and sometimes as co-writer (including of “Waymore’s Blues,” a song basically stolen from Furry Lewis, though Jerry later paid Furry)—and that’s the name he was married under on the stage of Nashville’s Exit / In while running from the FBI. His main Waylon duties were getting the man to his next gig and collecting the money due. He carried a briefcase full of cash and a very large handgun; and he drove on a driver’s license he could not show the law.

When last released from prison—his third long stint in two states under two names—his friend Paul Clements showed him a computer and said, “This is the Internet.” Jerry said, “Put my name in there,” and they did, and found him profiled on a blog, Boogie Woogie Flu. Scrolling the comments about himself, McGill saw a message from his 1959-era Memphis girlfriend, Joyce. Fresh from prison, he joined her in Alabama, and days later attended a North Mississippi Allstars gig—Jim Dickinson’s sons—letting them know he was looking for their dad. Free, in love, and playing guitar, he was dealt a sudden blow: lung cancer. He declared he’d make good music before he died and booked a day at Sam Phillips Recording Service in Memphis.

Jerry McGill, with aliases. (Courtesy of Robert Gordon)

My Irish film partner, Paul Duane, had been corresponding with Joyce for a couple years (having found her in the same comment thread on that blog). When Jerry showed up, she called Paul, and he called me. Joyce e-mailed me some stories Jerry had written—they were very well written—and I found myself on the phone with the long-lost Memphis outlaw. I told him how much I liked his writing, and he said, “Give me your address, I’ll send you more.”

Time stopped in that moment. For twenty years I’d maintained a PO box for just such occasions, but I had let it expire a while back. McGill was seventy now and, I reasoned, he couldn’t be the same dangerous man today. Was it really a risk? I gave him my address.

McGill was a professional criminal. He never let me forget that he knew where I lived, knew my routines. (Once, a few years later, he rang while I was driving. “You heading to your weekly workout?” Damn, he was good.) And he was a junkie. During the making of the film, he and Joyce got in a fight, and she kicked him out of the car and drove back to Alabama. Jerry was wandering the Memphis streets, needing a fix, with my home address. I was on my way out of town, so I showed his photo to my wife and two kids, one barely a teenager, and explained that if he showed up at the door, no matter what he said, they could not let him cross the threshold.

Paul and I and cinematographer David Leonard videotaped McGill’s final recording session, when he was joined by Memphis greats like Sid Selvidge, Jimmy Crosthwait, and Jim Lancaster, as well as Luther and Cody Dickinson. He was so good on camera—just like he’d been with Eggleston forty years earlier—that we saddled up and rode with him. He was an artist expressing himself in song. He was a budding short-story writer of considerable talent. Free again, he was establishing a home, drawing on the honeymoon feel of his renewed, deep-rooted relationship. And he was a hot-tempered man always armed with both knives and guns (including a very ornate sawed-off shotgun), despite the risk of mandatory prison as a convicted felon. He stole a cell phone off a neighboring table while dining out with us. (We made him return it through the restaurant’s mail slot.) In our presence, he threatened his best friend, his girlfriend, and people who’d never be his friend. We held tight until ten weeks later when we jumped off the Jerry McGill marauding maelstrom, fearing for our lives, our sanity, and our movie.

I remember phoning Joyce at one point, after a particularly harrowing outing with Jerry. I told her, “We had no idea that things were going to play out like this.” And she said, “I didn’t either. I hadn’t seen him in forty years. I’m as new to him as y’all are.”

McGill’s musical tracks were squirreled away by several associates, and as we found them, a larger picture of McGill’s talents emerged. The greats wanted to play alongside him. Mud Boy and the Neutrons in the 1970s sessions that Jim Dickinson produced (featuring some of their best-ever performances, with Lee Baker’s guitar on “Desperados Waiting for a Train” sounding strung with prison wire). Waylon Jennings and his Waylors joined the Memphis Horns to back him, and guitar great Travis Wammack later leapt to the call. His last session featured the North Mississippi Allstars and his first session Sun’s Little Green Men: Roland Janes, Billy Lee Riley, and J. M. Van Eaton. Paul and I found evidence of a Curtis Buck master, but we were unable to track its owner. McGill lost more master tapes than most people ever record.

Things mostly worked out for McGill. Joyce, who knew him before he was Curtis Buck, dug down to the nice guy beneath the thick skin, the one she’d known in the 1950s. After filming was complete, she saw him through his illness—with the understanding that she’d monitor the pain pills—and they lived several happy years together. The two of them were early rock and rollers who’d met in the shade of Sun Records, and they were sharing their sunset years, lying in bed with their heads together, one humming a tune and the other guessing its name.

But that happened mostly when we were done shooting. In Very Extremely Dangerous, Memphis’s real-life outlaw is battling death, and battling life itself, seeking peace, making war. Joyce demonstrated the power of love, and Jerry’s transformation was nothing less than unforeseeable. Both of them were revelatory experiences. Me and Paul, we took a thrill ride with a career criminal living his last days, and while he was someone I may not have wanted in my house, by the end, he was someone I was glad was in my life.