Chapter 10

Freddy had an alarm clock that always went off an hour earlier than it was set for. He said he liked it better that way. If he had to get up at six, he set it for seven, and then although he really knew that he would be getting up at six, he could think as he dropped off to sleep: “Seven. I don’t have to get up till seven.” It didn’t seem nearly as early doing it that way.

He set the clock for six the next morning, and at five ten he was up and out—for it doesn’t take a pig long to get dressed—and started to make a number of early morning calls. He called on Hank, and the cows, and Mr. Pomeroy, and Charles, and they all giggled and agreed to do what he wanted them to; and then he sent word to all the other animals on the farm. And after that was all settled he went down to the bank.

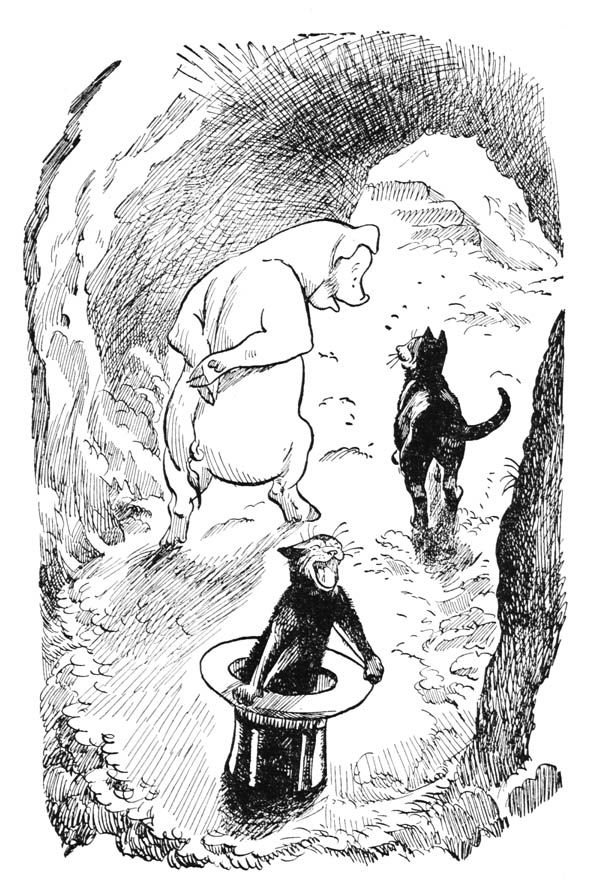

He opened the door and looked in. Jinx was curled up in one chair and Minx in the other, and Signor Zingo’s hat was in the middle of the floor. The two rabbits who were the regular night guards were at their posts on the trapdoor to the vaults. But there was no sign of Presto.

“Hey!” said Freddy. “Fine pair of jailers you are! Where’s the prisoner? Escaped, I suppose?”

The cats jumped up and both began explaining at once. Presto had vanished. He had done his disappearing act in the hat for them several times, but the last time he had refused to reappear again. “Goodbye,” he had said; “I’m going back to Centerboro,” and after that hadn’t answered when they spoke to him. “We thought he must still be in the room,” Minx said, “because even though he was invisible, he would have to open the door to get out.” But they had searched the place so thoroughly, even pawing about gingerly inside the hat, that they were sure they’d have caught him if he’d been there. He was just simply gone.

Freddy smiled to himself. He had a pretty good idea what had happened. Presto had probably got sick of hearing Minx talk, and had curled up quietly in the secret compartment of the hat. And indeed, when he spread a piece of paper over the hat and said: “Presto, change-o!” and took the paper off, there was the rabbit, sitting up and blinking sleepily at them.

Freddy went and opened the door. “All right, Presto,” he said. “Beat it!” And in three jumps Presto was out of the hat, out of the door, and in the middle of the road. And he disappeared down the highway like a small white stone being skipped across water.

“What did you let him go for?” said Jinx. “We might have made him show us how to disappear too.”

“Did I ever tell you about that conjuror I knew in India?” Minx asked. “He—”

“Sure, sure; forty times,” Freddy cut in. “Listen, anybody can disappear in that hat. I’d like to do it myself, only I’m too big to get in it. But why don’t one of you try it? How about you, Jinx?” He looked warningly at his friend and shook his head slightly, and Jinx, realizing that something was up, said: “Why, I’d like to, but—er—”

“Ladies first, eh?” said Freddy. “All right, Minx. You try.”

So Minx got in and Freddy put the paper over her. He rattled it a good deal, and under cover of the sound whispered rapidly in Jinx’s ear. Jinx’s face broke into a delighted smile, and he stood back, and then Freddy said the magic words and whisked the paper off. And there of course was Minx, sitting in the hat.

“Just as I thought,” said Freddy. “She’s vanished all right.”

“Completely gone,” Jinx agreed.

“I’m right here,” said Minx. “Do you really mean you can’t see me?”

“Did you hear anything?” said Freddy.

“Thought I heard a faint mew,” said Jinx. “Are you there, sis?” Both animals peered earnestly at a point just above Minx’s head.

“Certainly I’m here,” she said crossly. “Can’t you even hear what I say?” She jumped out of the hat and walked over to Jinx and cuffed his ear.

Jinx didn’t look at her. “Funny,” he said; “I thought something just touched my ear. Very light and delicate, though—like a butterfly’s kiss. Or I could have imagined it, I suppose.”

“Probably,” said Freddy, who was still peering into the hat, and feeling around the inside. “No, she’s not here. Queer we don’t hear her say anything, though. I could always hear Presto.”

“You big ninnies!” said Minx angrily. “I’m right here in front of your stupid noses! Look at me, can’t you?” And as they continued to gaze worriedly around into the corners of the room: “I don’t like this!” she wailed. “You let me out of here!”

Freddy had gone over and was feeling of the chair cushions. “Not here,” he said. “My goodness, Jinx, suppose she’s really vanished. I mean, not just invisible, but really—gone! Wouldn’t that be awful!”

“Terrible,” said Jinx calmly.

“Your only sister, too,” said Freddy.

“Yeah,” said Jinx.

“I tell you what,” Freddy said: “Let’s try the magic words again. Maybe she’ll come back.” And as he picked up the paper, Minx jumped back into the hat.

But the magic words didn’t work. When Freddy took off the paper, both he and Jinx professed to be unable to see her. And though she wailed and cried and protested and finally called them a lot of unladylike names, they still pretended she wasn’t there. At last Freddy said: “Well, there’s no sense staying here. We can come back later and try again.”

“Well, there is no sense staying here.”

“OK,” said Jinx. “I expect she’ll come back some time—she always does. Of course, she’s really a darned nuisance with all that everlasting gabble of hers, but I’d sort of hate to lose her entirely, at that.”

“Sure you would,” said Freddy. “Sure you would. After all, a sister’s a sister, no matter how silly.”

“Ain’t it the truth,” said Jinx.

Minx followed them up to the barnyard. She had stopped yelling by this time, because there’s not much satisfaction in bawling people out if they don’t hear you. I guess she had thought at first that Freddy and Jinx were just putting up a game on her. But when she reached the barnyard she was really convinced that she was invisible. For on his early calls that morning Freddy had warned all the other animals to pretend that they couldn’t see or hear her, and so when the three of them walked into the cow barn, the cows said good morning to Freddy and Jinx and then asked where Minx was.

“Vanished,” said Freddy sadly. “Disappeared. Dissipated into nothingness like the smoke from yesterday’s kitchen fire.” And he told them about it.

“Tut, tut,” said the cows together; “how dreadful!”

“Very sad,” said Freddy. “Can’t even have a funeral, you see.”

All the while Minx was walking up and down in front of them, lashing her tail angrily, and saying: “But I’m right here! Oh, darn you, Freddy! I wish I’d never come to this horrible farm!”

“Very sad for you, Jinx,” said Mrs. Wiggins soberly. “But we must look on the bright side of things. Minx was a charming person, but if you were with her very long you had to wear ear plugs.”

“Blessings sometimes come in disguise,” said Mrs. Wogus piously.

“Of course,” said Mrs. Wurzburger, “if there’s anything we can do, don’t hesitate to call on us.”

“Thank you, my friends; thank you,” said Jinx in a subdued voice. “You are all very kind. I suppose it will take some time for me to get used to the fact that Minx is no longer with me. Not to hear her voice going on, and on, and on …” He put a paw over his eyes.

The cows drooped their heads mournfully. Minx, with her tail sticking straight up in the air, walked past them, and the tip of her tail just brushed across their noses and tickled them. If she hadn’t been so scared and mad, she would probably have thought of some better way of bothering them, for of course they all exploded at once in a tremendous sneeze, and Minx was blown right out of the barn door.

Freddy and Jinx exploded too, in a laugh. They straightened out their faces, and Freddy said: “Pardon my unseemly merriment. Unforgiveable at a time like this.”

“Not at all, not at all,” said Jinx. “I’m sure Minx would want us to be gay.”

“I don’t know what got into us,” said Mrs. Wogus. “Touch of hay fever, perhaps.”

“Your sister is not to be sneezed at,” said Mrs. Wiggins.

All the rest of the day Minx had a pretty hard time. Wherever she went, the animals ignored her completely. She would try to break into a conversation with some bragging remark about something she had seen or done, just as she used to do, but the animals went right on talking without looking at her or giving any sign that they knew she was there. To Minx the queerest thing about it was that they were so often talking about her. That wouldn’t have surprised her so much if they had been praising her, for of course she thought that she was pretty wonderful. But the things they were saying weren’t nice at all. The first few times she heard someone say that she was a pest, and that it was a fine thing for everybody that she had vanished, she was angry and said to herself: “Pooh, they’re just jealous of my superior brains!” But after a while it began to sink in that she wasn’t nearly as popular as she had thought. And along in the afternoon she went back to the bank and curled up in a chair and tried unhappily to take a nap.

Freddy and Jinx, in the meantime, had hitched up Hank and driven down to Centerboro to get the sawing-in-two box and other magic paraphernalia. On the announcement board in front of the movie theatre was a big sign:

SIGNOR ZINGO

Formerly with Boomschmidt’s Stupendous

and Unexcelled Circus

Offers an evening of

REAL MAGIC

Conjuring, Mind-reading, Illusions

Recently on this stage an amateur performed certain simple, rather childish tricks. Now come see a professional performance.

Tuesday, Sept. 2 8 P.M.

Admission 50¢

CHALLENGE

To any person or animal who can duplicate, or explain, any feat which I perform, I will give $10 in cash for each trick so exposed.

(signed) ZINGO

The three animals read it in silence. Then they looked at one another.

“My good grief!” said Hank. “Why, that’s kind of an insult, ain’t it, Freddy? Amateur—ain’t that a fighting word?”

“Well, not really,” Freddy said. “It’s true. But he’s not a very good sport, calling my tricks childish.”

“The big yap!” Jinx snarled.

“He’s trying to make himself look like a good sport with that ten-dollar offer,” said Freddy. “But he knows I can’t duplicate his tricks. And though I can sort of guess how some of them are done, I can’t really explain them. We know the sawing-in-two trick, but of course he won’t take a chance doing that one.”

“I’d like to give him a piece of my mind,” said Hank. “With a couple of good hard iron horseshoes on the side.”

“He isn’t going to get away with it,” Jinx said. “We’ll-we’ll … what’ll we do, Freddy?”

Freddy shook his head. “I don’t know. I don’t think there’s anything we can do. We can’t explain or … Hey, wait a minute!” he said. “I bet I know! Look, are you two boys with me? I mean, it’ll be burglary, sort of, and maybe trouble if we get caught, but—”

“Burglary?” said Jinx. “Boy, I’ve always wanted to burgle. Runs in the blood; my father went into burgling when he lost his voice and had to give up singing. He could go up the side of a house like he was walking up Main Street, and he could ooze through a crack you’d swear wouldn’t accommodate a garter snake. But he oozed once too often. Lost half his tail when Mrs. McLanihan’s icebox door blew shut just as he was starting home with a couple pounds round steak. Couldn’t keep his balance on fences and roofs after that with only half a tail.”

“OK, OK,” said Freddy impatiently. “Your reminiscences of happy family life are delightful, but we’ve got a lot of work to do. How about you, horse? I don’t mean we’re going to steal anything. Just look over Zingo’s magic equipment.”

“Oh, sure,” said Hank. “Anything you say, Freddy—burglary or what not. As long as it ain’t murder. I kind of feel we ought to draw the line at murder.”

“Oh, that’s all right,” said Freddy with a grin. “You’ve got to draw it somewhere, Hank. Well, come on; let’s get that stuff. I want to go see the sheriff before we start home.”