Chapter 12

Disguised as Marshall Groper, Freddy walked into the hotel lobby. He hadn’t worn the sailor suit after all. For one thing, it was fifty years behind the style, and for another, Freddy felt that he looked foolish in it. Which of course he did. So he went into the Busy Bee Department Store and bought an Indian suit, complete with feathered war bonnet and fringed leggings and maybe he looked foolish in that too, but the war bonnet was certainly a good idea, for it partially concealed the feature that was most likely to give him away—his long nose.

Nobody paid any attention to the rather stout little boy in the Indian suit who put his suitcase down by the desk and was warmly greeted by Mr. Groper. He was shown up to a room which Mr. Groper said was “contiguous to that currently occupied by Signor Zingo.” Freddy had brought a small dictionary along, for he thought it might be useful in his conversations with his new uncle, and he got it out of the suitcase and found what contiguous meant.

Then he unpacked the suitcase and I guess a lot of people would have been surprised to see what was in it. There were four mice in it, for one thing, and they were pretty cross, for they had been shaken up quite a lot when the porter had carried the bag upstairs. Jinx was in it, too, and there were some tools (for burgling operations), and a couple of spare disguises, and a notebook and pencil (in case Freddy felt like poetry), and some magic apparatus, and a toothbrush, and a lot of other things. And the last thing Freddy took out was a small box in which were his friends, Mr. and Mrs. Webb, the spiders. Freddy let them out right away, and they went for a walk on the ceiling to stretch their legs.

As soon as he had got things unpacked and put neatly away in bureau drawers, Freddy gave his friends their instructions. He could hear Signor Zingo moving around in the next room, so he was careful to speak very low. There was a locked door between the two rooms, and he set the mice to work gnawing a hole in the lower corner. Then after the Webbs were rested, he had them try the keyhole. But the key was in it on the other side and they couldn’t get through.

“Maybe his window’s open,” said Mr. Webb. “If you’ll put up this window I’ll walk across and see.” So Freddy opened the window, and in a few minutes Mr. Webb came back. Freddy put his ear down close to the spider. “Shut,” said Mr. Webb. “But he’s there. Practicing card tricks in front of the mirror. And Presto’s asleep on the bed.”

“OK,” said Freddy. “Boys,” he said to the mice, “you’re making an awful racket with that gnawing. Maybe you’d better lay off until Zingo goes down to supper.”

The mice stopped working. “Freddy thinks, we’re too gnawsy,” said Eek, and they all laughed uproariously. Though of course there wasn’t much uproar—only squeaks.

Freddy went down early to supper. He wanted to get into the dining room before Zingo did. He sat with Mr. Groper at a table in a corner with his back to the rest of the room. But the magician, when he came in, walked straight over to their table.

“Ah, Mr. Groper,” he said, “I see you have company. Present me to your little guest.”

Mr. Groper said: “Signor Zingo—Marshall Groper, consanguineous with me on the paternal side, him being offspring of my fraternal relative.”

“Well, that’s one way of looking at it,” said the magician, and held out his hand. “How do you do, Marshall?”

“I do all ride, thag you,” said Freddy in a stuffed-up voice, and sniffed. He pretended to have a cold to disguise his voice. He didn’t shake hands, and Zingo drew his hand back and put it in his pocket.

“You don’t seem very glad to see me,” he said. “I guess you don’t know who I am, do you, Marshall?”

“Sure,” said Freddy; “I doe who you are, you’re the bagiciad that do’d ever pay by uggle adythig.”

Zingo pretended that he hadn’t understood. “I don’t ever what? Has the boy got an impediment in his speech?” he asked Mr. Groper.

Mr. Groper started to say something, but Freddy said: “I guess you’ve got an impediment in your pocketbook, haven’t you?” Only of course all his m’s were b’s, and all his n’s were d’s. When you read it you can hold your nose and it will sound the way it did when Freddy said it.

“Dear me,” said Zingo, “what a rude little boy!” He stared distastefully at Freddy who was trying to keep his face turned away. “And why, Mr. Groper, do you let him come to the table with a false face on?”

“Gee, I wonder if he has recognized me!” Freddy thought. “I guess I’d better get rid of him.” He said in a loud voice: “I should think you’d be ashamed to come in this dining room, when you don’t ever pay your hotel bill!”

Everybody in the dining room stared, and Mr. Groper said: “Ain’t you being a little contumelious, Marshall?”

Signor Zingo smiled his tight smile and put a hand on Freddy’s shoulder. “Oh, come, my little man,” he said, and pinched the shoulder viciously.

Freddy gave a loud squeal and wriggled away. “He pinched me!” he squalled. “The big bully!” And he began to cry.

Signor Zingo took his hand away quickly. He looked around at the other diners with raised eyebrows. Everyone glared, and a voice said: “Shame!”

“Aw, I never touched the big baby!” said Zingo; then he shrugged and went on to his table, where he sat with his back to Freddy, fingering his moustache.

Freddy felt that he had made a good beginning. Zingo’s temper had betrayed him, and the story of how he had maltreated a child would go all over town, for a number of Centerboro business men had witnessed the performance. As a disguise, the Indian suit had been a good idea. And the war bonnet was the best part of it, for it was built up with a circle of eagle feathers around the head and a long tail of eagle feathers down the back, and so when people looked at it they just looked at the headdress and not so much at the face under it. That was probably the reason why nobody recognized Freddy, or saw that the face under the war bonnet was a pig’s and not a little boy’s.

After dinner Freddy went up to his room. The mice had gnawed through the door, and had gone into Zingo’s room, but they hadn’t been able to look around much because Presto was still there. The Webbs, however, had gone in, and had spun themselves a little hammock up in a corner of the ceiling where they could sit comfortably and see and hear everything that went on. For the moment there wasn’t anything to be done, so Freddy took off his war bonnet, got out his pencil and paper, and settled down to a little poetry. This is what he wrote:

O the swallows fly about the sky,

And they swoop among the trees,

And they catch small bugs in their little mugs

And swallow them down with ease.

It’s fun, no doubt, to whirl about

In a swift and airy jig;

But as for me, I’d much rather be A pig.

The rabbit, at night, when the moon is bright,

Waits till it’s nearly dawn;

Then out he hops, with his friends plays cops

And robbers upon the lawn.

It’s fun, I suppose, to wriggle your nose

And live on a lettuce diet;

But it’s not my dish, and I wouldn’t wish To try it.

O cats are slim and full of vim

And they stay out late at night;

They’re merry blades, who sing serenades

On the fence, by the moon’s pale light.

It may be fun to wash with your tongue

And sing like the late Caruso,

But I’ll tell you square, I wouldn’t care To do so.

Now take the pig. His brains aren’t much big–

ger than cats’ or swallows’ or rabbits’,

But in debate his words carry weight,

And he’s formed very regular habits.

Pigs know all the answers; they’re conceded as dancers,

To be light as a bird on a twig.

So it mustn’t gall you if people call you A pig.

He was polishing up the last two stanzas, which seemed to have too many words in them, though he heartily concurred in the sentiments expressed, when Mr. Webb crawled up over the edge of the paper and began waving his feelers to attract his attention.

“News for you, Freddy,” said the spider. “Minx has just called on Zingo. She’s told him that his hat was in the bank—our bank, I mean—and he’s getting ready to go out there and break into the bank and get it.”

“Wow!” said Freddy, jumping up, and the poem fell unnoticed to the floor. It was later picked up by the chambermaid, who was so impressed by the lazy happy life led by pigs that she cried for several days because she couldn’t be one.

Jinx and the mice, who had been asleep on the bed, jumped up too, and they crowded around Mr. Webb to hear his story. Minx had wanted to get back at Freddy for the trick he had played on her, so she had told Signor Zingo that his magic hat was in the First Animal Bank.

“But I know that,” Zingo had said. “Presto saw it there.”

“But you don’t know how to get it,” Minx said.

No, the magician had said; he didn’t. He understood the place was guarded night and day. And he wasn’t going to give Freddy any hundred and thirty dollars for its return.

So Minx said she knew how to get in, and if he’d take her out there she’d help him get it.

“Well, come on,” said Freddy. “What are we waiting for?”

“You can’t beat them to it,” said Mr. Webb. “He’s getting ready to leave now, in his car.”

“Then so are we,” Freddy said. “Come on, Jinx. You others stay here.”

“Watch out for Zingo,” said Mr. Webb. “He’s got a pistol.”

They hustled down the back stairs and into the garage, and when a few minutes later Minx and Zingo came out and got into the car, the two animals were already in it, huddled together under a rug in the back seat.

As soon as they were out of town Zingo stepped on the accelerator and the car bounded swiftly up the road to the Bean farm. And Freddy and Jinx bounded with it. Freddy had thought that he could think up a plan of action on the way out, but he was too busy hanging on, and keeping from being smothered under the rug and being clawed by Jinx, to do much connected thinking. Jinx of course couldn’t see anything, and to keep from being thrown about and bruised, he dug his claws into whatever was handy, and as Freddy was a good deal handier than anything else he dug them into Freddy. Freddy said afterwards that if he could have squealed it would have been much easier.

Zingo drove beyond the Bean farm, turned around, and then drove back and stopped the car a little beyond the bank. He and Minx got out and Minx said: “If you cut that bell rope high up, next to the clapper, then if the guards get away from us they can’t reach it to ring the alarm.” And before Freddy and Jinx got disentangled and out of the car, they heard Zingo open the bank door.

“Darn it!” said Jinx disgustedly. “Are we stuck or are we stuck?”

“Yeah,” said Freddy. “We can’t capture him now. But wait! Help me get this rug out and up to where they climbed the fence.”

There was commotion in the bank and a flashlight flickered through the window as they dragged the rug up to the rail fence. Freddy whispered his instructions, and then they waited. Pretty soon the beam of the flashlight shot down towards them and was then shut off, and they heard Zingo’s footsteps. He climbed the fence cautiously and behind him a little black shadow leaped to the top rail. But as it jumped down, Freddy, with the rug spread out, fell upon it. There was a great scrabbling and thrashing as Freddy struggled to pin Minx down and wind her in the rug.

“What’s the matter?” Zingo whispered. “Don’t make so much noise!” He stopped and directed the flashlight back at the sound, but Jinx stepped forward into the light.

“Nothing,” he said. “Put out that light! I just bumped my nose in the dark.”

Of course all cats look alike at night, and even in the daytime it wasn’t easy to tell Jinx and Minx apart. Jinx was all black, while Minx had a white chest and white forepaws. But Zingo didn’t notice the difference. “Well, come along,” he said.

By the time they reached the car, Freddy had Minx well wound up in the rug, and her squalls were so muffled that nobody could hear them a few feet away. He tucked her under one arm, climbed the fence, and hid behind the bank.

Just as Zingo, with his magic hat on his head, was getting into the car, Jinx said: “Say, look! while we’re here, why don’t we take all the money that’s in the bank vaults?”

“What money?” said Zingo.

“Why, Freddy keeps all his money there—and he made a lot last year with the circus. Mr. Bean has some money deposited there, too. And all the other animals. I bet there’s more than a thousand dollars.”

“Go on!” said Zingo incredulously. “You mean all that money is in an unprotected hole in the ground under that trapdoor? You’re kidding me.”

“But I’m not,” said Jinx. “Oh well, go on if you want to. I’m not going to let this chance go,” and he started back.

Zingo hesitated a moment, then he followed. As soon as they were in the bank, Freddy crept around to the door. Zingo lifted the trap, and the rabbits, whom he had shoved down into the vaults on his previous visit, and who had been ineffectually banging on the under side of the floor in the hope that someone would hear them, skittered off down the underground passage.

“Better let me get it,” said Jinx. “That passage is a tight squeeze for you, and it goes quite a way before you get to the room where the money is.”

“No doubt,” said Zingo suspiciously. “But I prefer to go myself. Just in case,” he said with his thin smile, “there’s another way out. You might get mixed up and go out the other end with the money.”

Jinx knew that there wasn’t any other way out, but he tried to look disconcerted, as if he had really intended to sneak off with the money. So he held up the trapdoor and Zingo crawled down the passage. And as soon as the magician’s feet had disappeared, he slammed down the door with a bang, and Freddy rushed in and they piled all the furniture in the bank on top of it. And Freddy added his weight by sitting down in one of the chairs, while Jinx rushed out to climb the tree from which the bell hung, to give the alarm.

The passage to the vaults was just about big enough to let Zingo crawl along on all fours, holding the flashlight ahead of him. When he heard the bang, he knew that he had been trapped, and he tried to turn around. But he couldn’t. He had to go on until he came to the first room. So that by the time he got back to the trapdoor, the big bell was sending its clangdong-bang! out over the dark and silent fields of the Bean farm.

Up in the cow barn Mrs. Wiggins heard it. “Trouble at the bank!” she shouted. “Come on, girls!” And followed by her two sisters she dashed out into the barnyard. As they galloped down across the fields towards the bank Robert and Georgie went bounding past them, while behind them they heard the clatter and thump of Hank’s iron shoes as he backed out of his stall and followed.

On her perch in the henhouse Henrietta heard it. She popped her head out from under her wing, and pecked Charles sharply on the shoulder. “Trouble at the bank! Stop that snoring and wake up!”

“Wh-what’s that?” Charles squawked. “Who hit me? Oh, it’s you, Henrietta. What’s the idea? I was just dreaming that—”

“Well, you aren’t dreaming now,” she interrupted, “and that’s the alarm bell.”

“The bank!” shouted the rooster, who suddenly remembered the peck of shelled corn and the fifty cents in cash that he had put in the vault for safekeeping. “Henrietta, you stay with the children. You’ll be quite safe if you lock the door. I must get down there right away!”

“Oh, yes?” said Henrietta sarcastically. “And what good would you be, may I ask? You’ll stay with the children yourself!” And she fluttered down and out of the door.

Up on the edge of the woods Sniffy Wilson, the skunk, heard it. He was out hunting with two of his boys. “Trouble at the bank!” he said. “Edgar, you run back and get your mother and the other children, and Thurlow, you run over and wake up Mr. Grundy, the woodchuck. He sleeps like a log—he’ll never hear the bell.”

And up in the Big Woods Old Whibley heard it. He had just swooped on a mouse but had miscalculated the distance and had come down rather heavily among some blackberry canes, while the mouse ran off giggling, and his niece, Vera, who was hunting with him, pretended not to have noticed. “Trouble at the bank!” he hooted. “Wretched animals—always in trouble! Always coming for help—most inconvenient times. Well, come along, Vera! Don’t just sit there!” And he spread his wings and floated softly down towards the bank.

Most of the animals, as they galloped along through the dark, could see only well enough to avoid running into trees or falling over fences. By the thump and patter of hoofs and paws all about them they knew that other animals were running beside them, but they had no idea whether they were many or few. But the owls, who can see fairly well except on the very darkest nights, had the whole farm spread below them. They saw dozens and dozens of animals all converging headlong on the bank—cows and dogs; Hank, and Bill the goat, and goodness knows how many rabbits; and there were skunks and woodchucks lolloping along with their clumsy gait, and a fox or two; and they saw Peter, the bear, and his two cousins, break from the woods and streak down the hill at a dead run. And all around them in the night sky were chirps and the flutter and beat of wings, for the birds were coming too.

Up in the farmhouse Mr. Bean heard it in his sleep. He stirred uneasily and mumbled: “Dinner! Land sakes, dinner time already?” Then he woke up. “Mrs. B.! Mrs. B.!” he said. “That’s the old dinner bell down on Freddy’s bank!” He leaped out of bed, pulled on his boots, grabbed his shotgun, and in his long white nightshirt and his white nightcap with the red tassel, tumbled down the stairs and out into the darkness.

Down at the bank Freddy had lit a candle so he could see what was going on. He sat in the chair, trying to make himself as heavy as possible as the trapdoor under him shook with the heaves of the enraged magician. He still held Minx, who had stopped struggling inside the blanket. The bell clanged and bonged and made so much noise that he couldn’t hear whether his friends were coming to his rescue or not; but he didn’t need to hear them—he knew they’d come.

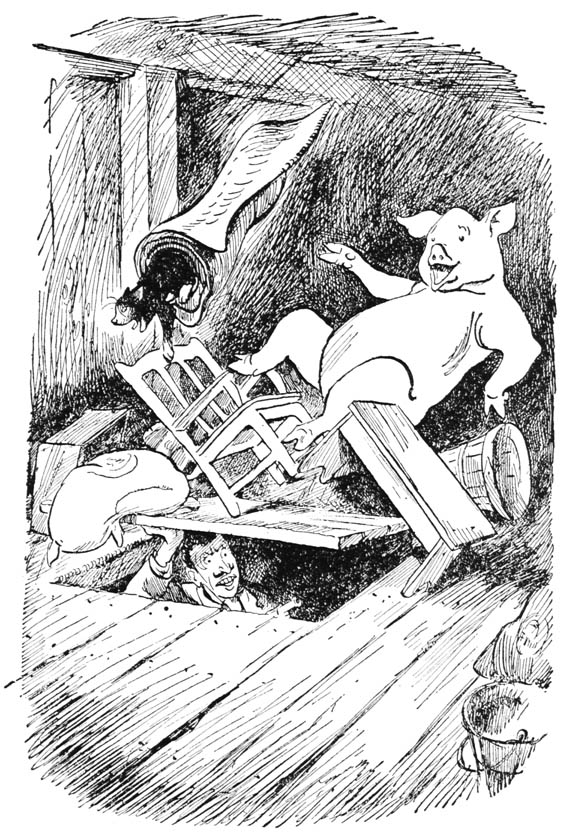

Then the scrabbling down in the passage stopped, and after a moment’s quiet there was a muffled bang, and something zipped up past Freddy and went through the roof with a click. For maybe half a second he looked up at the little round hole in the boards above his head. Then he gave a squeal and threw himself sideways so that he and the chair and Minx went over in a heap. And when presently the trapdoor was forced slowly up, and Signor Zingo’s sharp nose and a shiny pistol barrel appeared side by side in the crack, Freddy was outside peeking in.

Then he gave a squeal and threw himself sideways.

Zingo crawled out. He was covered with dirt and the expression on his face wasn’t pleasant to see. Outside, the bell had stopped ringing, and he could hear plainly the rush and trampling as the animals closed in. For a moment he hesitated; his magic hat had been knocked off in the passage and left there; but there was no time to go back for it. He ran out the door and made for the fence.

He was just in time. As he went over the fence, Robert made a snatch at him, but the collie’s narrow jaws snapped shut on the tail of the long red-lined cape. Robert held on, and Zingo went on without it, just as Mrs. Wogus and Bill, the goat, came crashing into the fence behind him.

The fence held up the pursuit just long enough for Zingo to reach his car. The smaller animals went through or over, but alone they were too weak to tackle the magician, and the bears, who could have gotten over easily, hadn’t yet come up. The two dogs got over, but the car door was shut and Zingo was inside stepping on the starter before they could reach him. And by the time Hank had turned around and kicked enough rails out of the fence so the animals could pour through, the car had begun to move.

Zingo had a terrible temper, and the thought of being done out of his hat and a thousand dollars by a lot of farm animals made him lose it completely. He glanced back and saw that the chase had been given up; the mob of animals made a darker blot on the darkness of the road behind him. He stopped the car with a jerk, leaned out, and aimed his pistol to shoot into the crowd. And Old Whibley, who had been cruising along, waiting for a chance, swept noiselessly down. His long sharp talons closed on Zingo’s hand, and the magician gave a yell and dropped the pistol. Vera swooped and picked it up, and as Zingo, grinding his teeth with pain and anger, drove on towards Centerboro, the two owls, without saying anything to Freddy, flew back to their nest.

Back in the road everyone was shouting at once and asking questions, and Freddy was trying to explain, when they heard the clump, clump of Mr. Bean’s boots coming along the road. The voices died down to a respectful silence as the farmer came up. It was like Mr. Bean not to ask any questions. He always said that if his animals needed his help, he was there to give it; otherwise he thought it was better for them to manage their own affairs.

All he said now was: “Everything all right?”

“Yes, sir,” said Freddy. “It was a burglar. We drove him off.”

Mr. Bean gave a grunt which might have meant anything. Freddy thought it meant: “Good work!” but it might just as well have meant: “Lot of fuss about nothing!” Then he said: “Pretty late. Better get to bed.” And turned and stumped off.

But the animals weren’t as easily satisfied. Freddy had to explain everything, and make a little speech thanking them all. It was nearly eleven o’clock when he and Jinx at last started back for Centerboro with the red-lined cape in a bundle under his arm.