Chapter 13

Freddy had dropped Minx when he had fallen out of his chair in the bank and nothing had been seen of her since. He and Jinx agreed that probably nothing would be seen of her for some time to come. The farm wouldn’t be a very pleasant place for her, and they both felt that she had probably started out on her travels again and that the next that would be heard of her would be a postcard from Quebec or Buenos Aires, with a line or two saying that she was being entertained by the mayor and had been given the keys of the city.

They were pretty surprised therefore when she overtook them a mile down the road.

At first they wouldn’t have anything to do with her. She begged and pleaded to be allowed to come with them. “I don’t know what got into me to do a thing like that, Freddy,” she said. “I was mad at the trick you played on me, but really and truly I am terribly sorry, and I’ll do anything if you will forgive me.”

Freddy didn’t say anything, but Jinx said: “You’d better stay invisible, sis, if you know what’s good for you. I’m your brother or I’d knock your head off; but there are a lot of animals back there that aren’t your brother, and you’d better keep away from them.”

Minx said meekly that she wished he would knock her head off—she’d feel better about it; and she followed them, weeping and wailing, until Freddy finally took pity on her. “Look here, Minx,” he said, “if you really mean it—well, I know you won’t go to see Zingo, after tonight—he thinks you shut him in the bank vault. So if you want to come along with us, and will promise to do just as we tell you, and not talk us deaf, dumb and blind …”

“Oh, I will, Freddy,” Minx said. “I mean I won’t. I won’t say a word, I promise; I’ll be just as still—you won’t hear a thing out of me, not a whisper—”

“And now,” Freddy interrupted firmly, “is the time to begin.”

So Minx stopped talking and didn’t say another word all the way to Centerboro.

When they got back to the hotel the mice told them that Zingo had come in about half an hour before and had gone right to bed. But during his absence they had ransacked the room. They had found a lot of gadgets he used in doing tricks, and they described these to Freddy, and in one of his pockets they had found a box containing a number of beetles and caterpillars.

“We let ’em out,” said Quik. “Poor things, they were almost suffocated. I hope it was all right to do that, Freddy. We thought it was cruelty to animals or something.”

“Cruelty to bugs,” said Freddy, “which is just as bad, though lots of people don’t think so. Sure it was all right. I suppose he’s collected them to drop around on people’s plates in the dining room if Mr. Groper starts talking about his bill again.”

“They were awful grateful,” said Eek. “They said if they could ever do anything to pay us back, just to call on them.”

Some people would have laughed at the idea that the assistance of a caterpillar or a beetle could be of any value, but Freddy had had extensive contacts with the insect world, and their help had at times been invaluable to him. He said: “Where are they now?”

“We opened the window for them,” said Quik, “but they said they guessed they’d stick around until you came back, just in case. They’re there on the sill.”

There were two large red-brown fuzzy caterpillars, and several smaller smooth green ones, and half a dozen assorted beetles, standing in a little group on the window sill. Freddy went over and thanked them for their offer, and then he called up Room Service and had some lettuce sent up for their supper. The fuzzy caterpillars didn’t like lettuce, and the beetles never ate it, but they didn’t like to say so when Freddy had gone to so much trouble, so they all politely ate a little. Then the caterpillars, who are not used to being out so late, curled up and went to sleep. I don’t know what the beetles did; they are like some people—it is hard to tell whether they are asleep or just thinking. But the green caterpillars liked lettuce and they sat up and ate it all night. They were quite a lot larger in the morning.

The mice also reported that several mousetraps had been set in dark corners of Zingo’s room. “He probably heard us gnawing yesterday,” said Eeny, “Or maybe Presto saw us.”

“You’d better be careful and not go fooling around there in the dark,” said Freddy.

Eeny grinned. “We put ’em where they’d do the most good. I guess he hasn’t hit the one we put in his bed yet. But there’s a couple others will get him sooner or later.”

“That gives me an idea,” said Freddy. “Remind me to buy a few tomorrow. And I think we’d better get some sleep; we’ve got a lot to do before Tuesday.”

Freddy was having breakfast with Mr. Groper next morning when Signor Zingo came into the dining room. He came straight up to their table, and Freddy was horrified to see that he had the cape with the red lining over his arm. The last Freddy had seen of it was when he had thrown it over the back of a chair in his own room when he had come in last night.

“Morning, Groper,” said the magician. “Maybe you can explain why I find this cape of mine in your nephew’s bedroom, eh? What kind of a hotelkeeper are you anyway? Serving caterpillars with the meals, and now having a sneak thief come to stay with you! If you’ve got anything to say before I call the police—”

Everybody in the dining room had stopped eating and was staring, and two guests who had come the night before got up and left the room hurriedly—presumably to check up and see if any of their belongings were missing.

Freddy said quickly: “I found this cape last night and took it to my room. It was too late to find out who it belonged to. Go ahead and call the police. I guess they’ll want to know how you got into my room—the door was locked.”

“I had a right to go in after my own property,” said Zingo. “I’ve suspected you were a crook all along, though it is hard to believe that one so young could be so depraved. But I suppose this uncle of yours put you up to it.”

Mr. Groper heaved himself to his feet. “You state,” he said, “that this here article of apparel is one of your chattels and appurtenances.” He seized the cape and examined it. “Tain’t provided with any legend, label or device that determines such ownership.” He tossed the cape back. “But I’m with you as to the advisability of summoning the representatives of the law. This young relative of mine has had his constitutional rights violated and trompled on. His private room has been burglariously and feloniously broke into. And I’m agoing to put myself into immediate telephonic communication with the sheriff.” He started for the office.

Zingo evidently realized that he had gone too far. He had found his cape in the room occupied by Mr. Groper’s nephew—but how had he got into that room? He had no wish to explain that to a judge. So he merely grumbled something about living in a den of thieves, and sat down to his breakfast pulling his moustache irritably as he ordered an extra portion of ham and eggs.

Freddy was worried. If Zingo had broken into his room, he might have discovered a good deal. He might have discovered that little Marshall Groper was just a pig in an Indian suit. And a pig who was his enemy. Freddy would have liked to go upstairs at once and find out what had happened. But he didn’t dare leave the dining room until the sheriff came. For although it would please Mr. Groper to have Zingo arrested and taken off to jail, it would mean that Freddy would probably never get his hundred and thirty dollars back. It would mean that there would be no magic show Tuesday night, and Freddy had laid very elaborate plans for that show. Also it would mean that the sheriff would have a very troublesome prisoner in his jail. For Zingo certainly wouldn’t fit in well with the other prisoners, who, as the sheriff often said, were just one big happy family.

Presently Mr. Groper came back and sat down with the remark that the representative of legal authority was momentarily anticipated.

“You mean the sheriff’s coming,” said Freddy, who was getting used to Mr. Groper’s language.

Mr. Groper smiled a slow, fat, kindly smile. “You—and—Sheriff,” he said very slowly, as if choosing his words with great care, “are about—the only ones—that ever know what—I’m talking about. You see, I’ve always had a predilection for this here sesquipedalianism. I …”

“Whoa!” Freddy interrupted. “Now you’re way beyond me.”

Mr. Groper nodded. “I mean,” he said, “big words. They were—kind of a hobby. Which it is bad. It habituates you to imperspicuity. I mean—you can’t find the little words when you want ’em. So that I ain’t able any longer to express myself in intelligible monosyllables. And though my oral communication is unambiguous, it …”

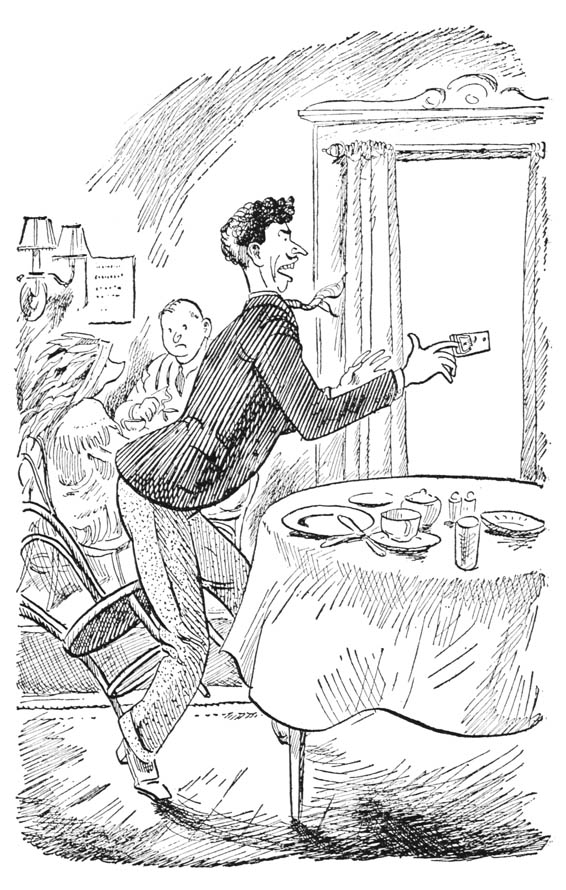

A loud yell and the scrape of a chair interrupted him. Freddy turned around. Zingo, who had put a hand in his pocket to get a cigar, had yanked it out again and jumped to his feet. From one finger dangled a mousetrap.

A loud yell and the scrape of a chair interrupted him.

“Look at that!” he shouted furiously. “That’s the kind of thing that goes on in this miserable dump you call a hotel!” He shook his fist at Mr. Groper who was slowly getting his feet under him so he could get out of his chair. “Treetoads in the orange juice, sneak thieves going through your rooms, and now practical jokes! And I know who’s responsible! If you won’t give this nasty little wretch a good hiding, I’ll do it myself, and now!” And as he advanced upon Freddy he whipped off his belt and swung it menacingly.

Freddy slid out of his chair and ducked around behind Mr. Groper, who by now was halfway up. He didn’t like the look of that belt buckle, and he knew the magician meant business. But just as Zingo reached for him, a voice from the doorway said: “What’s going on here?” It was the sheriff.

One of the guests pointed at Zingo. “That fellow got caught in a mousetrap,” he said. “He’s going to lick the boy for putting it in his pocket.”

“Caught in a mousetrap, eh?” said the sheriff. He shook his head. “Tryin’ to steal the cheese, I suppose. What some folks won’t do to get a little extra!”

“I wasn’t stealing the cheese, you fool!” snarled Zingo. “That boy put the trap in my pocket.”

“Kin you prove it?” said the sheriff. “And if so, what of it? Tain’t a hangin’ matter. Whereas this breakin’ into the boy’s room—”

“I don’t think he broke into it,” Freddy interrupted. “I remember now I left the door open, and if he saw his cape there, I suppose it was all right to go in and get it.”

The sheriff and Mr. Groper stared at Freddy in puzzlement. Why, they wondered, was he throwing away a chance to have the magician locked up? Zingo was puzzled too. But he had the good sense to go back to his chair.

The sheriff turned to Mr. Groper. “Well, Ollie,” he said, “I don’t see as there is anything for me to do here. Unless,” he said to Zingo, “you want to make charges against this wild Indian for illegally and with malice aforethought settin’ traps, gins, slings or snares with the intent of catchin’ and pinchin’ one or more digits, and thus causin’ you pain, alarm and vexation of spirit? How’s that, Ollie?” he said, grinning at the hotelkeeper.

But Mr. Groper was too disappointed at not being able to have Zingo arrested to applaud the sheriff’s elegant language. He merely shrugged and lumbered off towards the office.

The magician didn’t bother to reply either. He lit a cigar and called for another cup of coffee.

When the sheriff had gone, Freddy slipped up to his room.

“Hi, Big Chief Pretzel Tail,” said Jinx. “Take off that war bonnet: we know you. Say, there’s been a visitor to your wigwam while you were out.”

“I know it,” said Freddy. “How’d he get in?”

“With a key. We heard him try two or three, and then he got one that unlocked the door. Minx and I hid in the closet. I don’t think he came in to get his cape, because he acted surprised when he saw it. And he looked in all the bureau drawers.”

“He must suspect who I am,” said Freddy. “If he thought I was just Mr. Groper’s nephew, he wouldn’t snoop in here, and if he knew who I was, I don’t think he would either. He’s looking for evidence.”

“Well, he didn’t get much,” said Jinx. “We thought we’d better get rid of him, so we sneezed a couple of times and rattled things around in the closet, and I guess he thought the chambermaid was in there, because he sneaked right out.”

“He got enough,” Freddy said; “he got the cape. And he’s no fool; he can put two and two together. If anybody’s the fool, it’s me. I thought by coming here I’d be able to figure out some way of getting him to leave the hotel. But I haven’t accomplished anything, and …”

“Oh, you’re just breaking my heart!” Jinx interrupted sarcastically. “If we hadn’t come to the hotel we wouldn’t have known that Zingo was going to rob our bank, and he’d have cleaned the place out. We’re doing all right. Come on, chief, give ’em the old war whoop. Sharpen up your tomahawk. We’ll get Zingo’s scalp yet.”

“Oh, I’m not giving up,” said Freddy, but he didn’t say it with much conviction. If Zingo knew who he was, he might as well hang up the Indian suit in the closet and go home. For if he didn’t—well, it would be just too bad.

As a matter of fact, it was too bad—and no later than that afternoon.