This happy breed of men, this little world,

This precious stone set in the silver sea,

Which serves it in the office of a wall,

Or as a moat defensive to a house,

Against the envy of less happier lands.

Richard III, I, i, 47–51

HISTORY DOES NOT RECORD WHETHER DURING THE FIRST PERFORMANCE of Richard III, probably in late 1591, any in the audience gave a hollow laugh as John of Gaunt boasted that ‘this happy breed of men’ was safe from ‘the envy of less happier lands’. The plain fact of the matter was that during the last third of Queen Elizabeth's reign ‘this precious stone’ was plagued with war. Although the reign began fairly peacefully, by its last two decades England increasingly became involved in wars, on land and at sea, both abroad and in Ireland. In many ways the Armada of 1588 was a turning point. A great victory, it gave Englishmen both a degree of self-confidence and the recognition that they must fight a long, all-out war against Catholicism. War cost much money and many lives. Military service became the norm: about half of all adult males served in the armed forces in one capacity or another.1 England developed a highly effective military culture, which was reflected in numerous military manuals, many stage plays, and in tensions between soldiers and civilians.

Confrontation Postponed

Initially, the memory of the huge financial burden of Henry VIII's military escapades dampened any enthusiasm for war on the part of the queen and her advisers. Sir William Cecil, Baron Burghley, Elizabeth's pre-eminent counsellor, often complained of ‘the uncertainty of the charge of war’, the actual cost of operations being frequently thrice the amount that soldiers or sailors anticipated.2 Mercenaries were both expensive and unreliable. As Machiavelli warned, ‘How dangerous and pernicious it is of a Prince and his realm to be open to the trust of the service of strangers.’3 So Elizabeth tried to postpone confrontation. She gave Philip II of Spain (her late sister's widower) the impression that she was in fact a Catholic who wanted to declare her faith and even marry him, but could not do so until she was safely ensconced on the throne. Of course, this was all absurd, but it worked well enough to delay the Armada for a dozen years, during which time England grew stronger militarily.

When Elizabeth came to the throne, England could deal with weak enemies in Scotland but not powerful ones on the continent. In February 1560, two years into the queen's reign, an English army of two thousand men under the duke of Norfolk crossed the border, and after winning a skirmish besieged the French garrison at Leith. After three weeks they tried to take the castle in one last desperate assault. It failed. The scaling ladders were six feet too short. But the French had to surrender in June, having received no supplies from home.4 It was the last major Anglo-Scottish combat for seventy-nine years. Elizabeth used bribes to buy peace. ‘Money,’ declared Sir Francis Walsingham, her spymaster, ‘can do anything with that nation.’5 More important, Scotland became Protestant. The Anglo-Scots wars of the 1540s and 1550s severely weakened the Catholic Church north of the border: buildings and monasteries were destroyed, priests killed. So when John Knox returned from the Protestant reformer John Calvin's Geneva in 1559, Scotland was ripe for reformation and the spread of Presbyterianism.

While the Reformation brought peace with Scotland, it prompted wars elsewhere. In 1562, two years after the final expulsion of the French from Scotland, Elizabeth intervened in France to help the Huguenots, fellow Protestants, in rebellion against their Catholic king. She dispatched between five hundred and nine hundred English, Scots and Welsh volunteers to Normandy: for volunteers, their performance was mediocre, and they were readily defeated. Only 25 out of 120 men in Captain Henry Killigrew's company survived: those who did not die in combat or from disease were captured and executed or sent to the galleys. The debacle deterred Elizabeth from intervening on the continent for two decades.6

During this period the crown used the militia to deal with threats to internal security. The idea that all able-bodied men between sixteen and sixty were obliged to turn out to defend the realm went back to the Anglo-Saxon fyrd. In an early example of what today is called ‘cost shifting’, in the 1558 Horse and Armour Act Queen Mary's government transferred the financial burden of running the militia from the crown to its members by ordering that soldiers buy their own weapons. For instance, militiamen worth from £5 to £10 a year had to purchase an armoured jerkin, a steel helmet, and a halberd or longbow. At the other end of the scale, those worth over £1,000 a year had to provide sixteen horses, eighty suits of light armour, forty pikes, thirty longbows, twenty halberds, twenty harquebuses, and fifty helmets.7 In theory, service was compulsory for all adult males (except the clergy) from sixteen to sixty, who were required to turn up for a number of drills each year.8 To be sure, after training, the part-time soldiers might repair to a local tavern, where the entertainment must have helped foster a sense of a county community similar to that which their betters developed during the quarterly court sessions. Encouraged by a generous allowance of 8d. to 12d. a day, plus the prospect of liquid refreshments, most men were happy to train to defend their homes and families, especially when they believed that the threat was real. Within days seven hundred of Cambridgeshire's trained bands responded to the government's orders to mobilize to deal with a threatened invasion in 1599, ‘as though the enemy were at our doors’. Not everyone was as willing to leap into the breach. In 1595 William Pace explained why he could not attend the muster of Kent's cavalry contingent: ‘I am fallen into an infirmity called the piles, where I am scarce able to go much less sit upon a horse.’9

Even the least skilled militiaman had little difficulty in dealing with untrained and poorly armed rioters, who engendered an intense degree of fear and loathing.10 Far from conceding that rioters might have reasonable grievances, authors such as Edmund Spenser, Philip Sidney and William Shakespeare portrayed them as dangerous buffoons and pernicious simpletons with unconscionable demands. Shakespeare asserted that they wanted to buy seven halfpenny loaves for a penny.11

Much more dangerous than peasant revolts was the aristocratic rebellion that took place in 1569. Centred on Durham and South Yorkshire, begun by the duke of Norfolk (who had ambitions of marrying Mary, Queen of Scots), and led by the Catholic earls of Northumberland and Westmorland, the Northern Rebellion was an attempt to stop the growing centralizing power of the crown. It was also a reflection of a distinct military culture produced by centuries of border warfare, which the North's bellicose ballads reflected.12 The rebellion failed. The militia crushed it in six weeks. Although the rebellion was relatively bloodless, less than a dozen men losing their lives in combat, the queen ordered seven hundred rebels hanged, although 450 actually suffered the ultimate punishment.13

The Northern Rebellion was the last of a series of Tudor rebellions.14 The state was growing too strong, and the aristocracy was becoming too weak, to risk such desperate ventures. In the first half of her reign Elizabeth did much to bring about this change. To be sure, it took time to shape her regime. As it continued the queen ennobled fewer peers, and learned to control both parliament and the powerful men who believed that the Great Chain of Being—that divinely ordained hierarchy of class and gender—meant that they should direct a woman ruler.15 Elizabeth returned England to the Protestant faith, and became head of a Church that tried to follow the via media, the middle way that did not seek a window into any man's soul.

The Armada

Such policies stood Elizabeth in good stead in the last third of her reign when England faced its greatest military challenge. The Armada was the key event in a general European war that England fought for two decades, at sea, on the continent and in Ireland.16

The story of the Spanish attempt to invade England is so well known that it needs no long description, of how in April 1587 Sir Francis Drake ‘singed the king of Spain's beard’ by attacking the fleet he was assembling in Cadiz. Drake burned thirty ships, and destroyed vital naval supplies including wood being seasoned for making barrels. Next he blockaded Lisbon for a month, capturing Spanish merchant vessels worth £114,000. ‘It may seem strange or rather miraculous that so great an exploit should be performed with so small loss,’ Captain Thomas Fenner wrote to Sir Francis Walsingham. His explanation was simple: ‘our good God hath and daily doth make his infinite power manifest to all papists.’17 Religion was central to Elizabethan warfare.

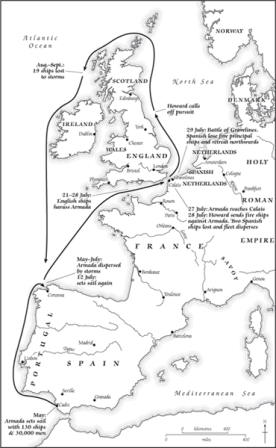

Drake's successes were not enough to stop the Armada from sailing in May 1588. It was commanded (most reluctantly) by the duke of Medina-Sidonia, a grandee who admitted ‘I have never seen war nor engaged in it.’ He was particularly loathe to serve aboard ship since he suffered sorely from seasickness. On 19 July his fleet of 130 ships weighing 58,000 tons, carrying 30,000 men and 2,431 cannon, arrived off The Lizard. They confronted about two hundred English vessels, crewed by sixteen thousand men. Although smaller, the English ships were faster, could sail closer to the wind, were better led and manned, and had twice as many long cannon, with three times the firepower. These advantages became apparent as the Spanish fleet sailed in a crescent formation up the Channel, being unceasingly harassed for nine days. On 27 July it finally reached Calais, close to the rendezvous to pick up the duke of Parma's army from the Spanish Netherlands, and transport it to conquer England. But Parma's army was not there. Worse still, the following night the English launched several fireships, panicking the Spanish. Some of their vessels caught fire, others cut their anchor lines and drifted aground on a lee shore or into each other. The next day off Gravelines the English followed up their attack by bombarding the enemy with their long-range guns.

2. The Spanish Armada, May–September 1588.

Battles are won less by killing the other side and more by destroying their will and ability to fight. In this the English succeeded. Morale broken, the Spanish were unable to face the long tack against the prevailing winds south and west back down the Channel, running a gauntlet of English cannon fire. (They did not know the English were almost out of ammunition.) So Medina-Sidonia ordered his fleet to sail north around Scotland and Ireland. Bad weather, including the remnants of an early hurricane, bad food turned putrid in barrels made from unseasoned wood, inaccurate charts, poor seamanship and plain bad luck meant that a third of Philip's ships and two-thirds of his men never made it home. Ironically, at the time many English sailors did not realize that they had won a major victory. On 8 August 1588 Henry White, captain of the fireship Talbot, which had helped win the decisive battle off Dunkirk but ten days before, complained that ‘our parsimony at home hath bereaved us of the famousest victory that ever our navy might have had at sea.’18

The Armada was not just a naval campaign. The build-up of land forces to resist a Spanish invasion has been described as ‘an administrative feat of massive scope’.19 A survey taken in November and December 1587 showed 130,000 men in the militia, of whom 44,000 were members of the trained bands, some of whom were extremely competent, being drilled and led by experienced captains and sergeants just home from the continental wars. By May 1588 the London bands were drilling weekly. To give warning of the enemy's approach, beacons were built, manned twenty-four hours a day by four men, paid 8d. a shift. Once the beacons were lit, 72,000 men could be mobilized on the south coast, with another 46,000 protecting London. In August the queen inspected her troops at Tilbury, where according to Thomas Deloney's ballad, ‘The Queene's Visiting of the Campe at Tilbury’ (1588), she told them:20

My loving friends and countrymen

I hope this day the worst is seen,

That in our wars you shall sustain

But if our enemies do assail you,

Never let your stomachs fail you

For the many Englishmen caught up in the Armada the experience must have been very profound and frightening. Some shared the intimacy of beacon watching, hoping for the best, but ready to light their warning fires in case of the worst. Deloney, a London silkweaver, played on their fears in his ‘New Ballet [Ballad] on the strange whippes which the Spanyards had prepared to whippe English men’ (1588). The political philosopher Thomas Hobbes recalled that his mother was so frightened that she prematurely gave birth to twins, of whom he was one. All were terrified about what might happen if the Spanish invaded. Stories of the sack of Antwerp in 1576, in which the Spanish—led by the aptly named Colonel Charles Fuckers—raped, tortured and murdered as many as seventeen thousand civilians, were grist for playwrights and pamphleteers such as George Gascoigne and Shakespeare. The former remembered seeing civilians at Antwerp drowned, burned, or with guts hanging out as if they had been used for an anatomy lesson.21 Few Englishmen, women and children doubted they faced similar fates had the Armada landed. A defence in depth and scorched-earth tactics would not have repulsed the Spanish, whose infantry was regarded as Europe's finest. Certainly Philip II's men would have taken the south-east and London, and perhaps captured or killed the queen. But rather than meekly accepting a Catholic occupation the English—like the Dutch—would surely have waged a long and brutal war against Spain.22

Few Englishmen doubted that their ‘scepter'd isle’ had escaped a terrible fate. Once again Thomas Deloney voiced the public's feelings. As his ‘A Joyful new Ballad’ put it:23

Our pleasant country,

so fruitful and so fair,

They do intend, by deadly war;

to make both poor and bare;

Our towns and cities

to rack and sack likewise,

To kill and murder man and wife,

as malice doth arise

And to deflower

our virgins in our sight.

Officially, the queen gave the Almighty credit for the defeat of the Armada, striking a medal proclaiming ‘Afflavit Deus et dissipati sunt—God blew and they were scattered.’24

The credit was not entirely His. The roots of the English victory went back a century or more. Elizabeth had built on naval foundations laid by her father. As we saw in the previous chapter, Henry VIII took advantage of the late medieval revolution in shipbuilding, producing new deep-hulled vessels, with three masts, and iron cannon firing through gun ports on the sides. But compared to the Dreadnought, which was launched in 1577, Henry's first battleship, Henry Grace à Dieu, and the even larger Mary Rose, were lumbering leviathans. Geoffrey Parker has written of a ‘Dreadnought Revolution’ in naval architecture that was as significant as the one that took place in the early twentieth century. Developed by Sir John Hawkins, the architect of the Elizabethan navy, the Dreadnought displaced seven hundred tons; it carried cannon weighing thirty-one tons, which amounted to 4.5 per cent of its total weight, packing a far heavier punch than Henry VIII's vessels, which had a 3.69 per cent ratio. This proportion continued to grow: averaging 6 per cent in the Armada, it reached 7.33 per cent by the queen's death.25 Shipwrights, such as Matthew Baker at Chatham, used geometric models to build longer—and thus faster—vessels with length/beam ratios of five to one. Sir Francis Drake called Baker's most famous creation, the Revenge, the ‘ideal ship of war’.26 Such vessels were remarkably seaworthy. They could sail across oceans, even around the world. During Elizabeth's reign no major Royal Naval vessel was lost at sea.27

First-rate ships required many first-rate men to man and maintain them. Sailing vessels needed large crews, not just to cover attrition due to disease and accidents, but simultaneously to ply the guns, trim sails and board the enemy. In 1562 parliament mandated the eating of fish on Wednesdays, in addition to Fridays, to encourage the growth of the fishing industry, a crucial reservoir of trained manpower. At the start of Elizabeth's reign Lord Admiral Edward Fiennes de Clinton, earl of Lincoln, and Lord Treasurer William Paulet, marquess of Winchester, developed the system of permanent warrant officers, such as boatswains, attached to each ship, to maintain her when laid up, and as a cadre upon mobilization.28 Sea fighting was a complicated task that demanded high levels of managerial and specialty skills. For instance, in 1588 the Crescent had twenty-nine officers, warrant and petty officers to command thirty-eight seamen, and three boys (as compared to an infantry company with two officers, two sergeants, and four corporals for a hundred and fifty men).29 Since the sea was such a dangerous place, it demanded competence on the part of sailors, unlike life on land where status and birth were far more important. Sometimes the two collided. At the start of Sir Francis Drake's voyage around the world in 1577–80, Thomas Doughty thought that his high birth and excellent court connections entitled him to be the squadron's commander, and so he staged a mutiny. Drake court-martialled and executed him, telling his men: ‘I must have the gentleman to haul and draw with the mariner and the mariner with the gentleman.’30

More often than not, gentlemen and mariners (who became known as tarpaulins) worked together—if only because the prospect of drowning encouraged cooperation—a stimulus that soldiers lacked. During the Armada, Lord Henry Seymour explained why a secretary was writing on his behalf: ‘I have strained my hand with hauling of a rope.’ To be sure, most naval captains had claims to gentility. Men such as John Hawkins or Francis Drake used naval careers not to join the gentry but to enhance their status within it. The sea could, as Drake put it, become ‘The path to fame, the proof of zeal, and the way to purchase gold.’31 Aristocrats who became captains were experienced sailors. Robert Dudley, the son of the queen's favourite, the earl of Leicester, studied seamanship and navigation from the age of seventeen, being the first Englishman to plot a grand-circle course, a very complicated mathematical feat. During Elizabeth's reign it first became acceptable for a gentleman's younger son to seek his fortune at sea.32

There were plenty of fortunes to be found there. Because wooden ships were relatively hard to sink and easy to capture, and were expensive prizes with lucrative cargoes, immense riches were to be made in privateering—a legalized form of piracy. Drake's voyage around the world produced a 4,700 per cent return, which did much to parry claims from the likes of Thomas Doughty that birth, not merit, made natural leaders. At sea, more than on land, in war, rather than in peace, necessity favoured not just the brave but the competent.

War at Sea after the Armada

The defeat of the Armada did not end hostilities: Spain's war machine was not broken. Indeed, during the next decade it was able to launch two more Armadas that, luckily for the English, storms turned back. Spanish raids on Cornish villages, such as Mousehole, Godolphin Cross and Newlands, were mere pinpricks. At Cawsand's Bay one man with a musket apparently drove the raiders away.33

Most Englishmen remained convinced that it would take more than a light carbine to thwart King Philip, who Sir William Cecil noted in 1590 wanted ‘to be lord and commander of all Christendom, jointly with the Pope and with no other associate’.34 To frustrate Philip's knavish tricks, England relied on sea power in three ways. First, the Royal Navy blockaded the Channel to prevent the Spanish from reinforcing their troops in the Netherlands and obtaining military supplies from the Baltic. In this the navy was remarkably successful. Less effective was the second English objective, seizing the Spanish treasure fleets from the Americas by capturing their ships at sea or in port. The third method, blockading the Spanish coast, was beyond the Royal Navy's grasp since it could not remain at sea for months, especially during the winter, lacking sufficient supply vessels to support it. So the English had to resort to privateers. One consistent theme ran through all these strategies. As Robert Devereux, second earl of Essex, put it, England's objective in fighting Philip II was to ‘cut his sinews and make war with him with his money’.35

Such was the guiding principle behind the expedition that Sir Francis Drake, as admiral, and John Norris, as general, led against Portugal in 1589. It was a large venture of eighty-three ships, sixteen thousand sailors and four thousand soldiers. Many of the latter were of poor quality. ‘The justices,’ complained Colonel Anthony Wingfield, ‘have sent out the scum of the county.’36 At first, the commanders disobeyed orders and attacked Corunna, where they believed a Spanish silver galley was moored. It was in fact in Santander, although in Corunna they did destroy three Spanish warships.37 Two weeks later Drake and Norris sailed for their original target, Lisbon, where they were equally ineffective. The Portuguese had been forewarned, and the English split their forces, failing to coordinate between the army and navy, the latter being intent on plunder. After an equally inept attempt to capture the Azores, Drake and Norris sailed for England, leaving over half their men behind dead, deserted, or prisoners. On returning to London, five hundred unpaid survivors looted St Bartholomew's Fair, prompting the city authorities to call out a thousand troops from the trained bands. All in all it had been a ‘miserable action’, thought William Fenner, one of the lucky ones to make it home. William Monson, another survivor, agreed, noting that Drake ‘was much blamed by the common consent of all men’.38 The queen concurred, hauling Drake and Norris before the privy council. Drake languished in disgrace at his Devon home until 1595, when once more he was allowed to attack the Spanish Main. He died at sea the following year.

In 1596 the English attacked Cadiz in what David Loades has called ‘one of the most efficient acts of war carried out by any Tudor government’ (see ill.8).39 For one thing the expedition's commanders—Essex, Lord Charles Howard, Lord Thomas Howard and Sir Walter Raleigh—worked well together, coordinating the efforts of seventeen Royal Navy ships, thirty Dutch vessels and seventy-three armed merchantmen. They held the town of Cadiz for two weeks, destroying twenty-four large ships, burning 1,300 buildings and inflicting £5.5 million pounds in damage. The English took booty worth £170,000 (most of which they surreptitiously appropriated, the bishop of Faro's library ending up in the Bodleian, Oxford), but failed to capture the Spanish treasure fleet. Elizabeth was outraged at the loss of so much plunder, as well as by the fact that the commanders knighted sixty men without her permission. Philip II was so angry that he dispatched another Armada of a hundred ships, which a winter gale shattered in the Bay of Biscay, sinking a quarter of the Spanish vessels.40

Afterwards the Anglo-Spanish naval war became basically a privateering conflict. Some Englishmen, such as Sir John Hippisley, used privateering as a way to get out of debt, others to make their fortunes. The capture of the Sao Phelipe in 1587 brought (after heavy looting) cargo worth a tenth of England's annual imports, while that of the Madre de Dios five years later, valued at half a million pounds, was worth 50 per cent of yearly imports. Between the Armada of 1588 and peace with Spain in 1603, privateering profits comprised 10–15 per cent of imports, while earning the queen an average of £40,000 a year, two-thirds of the cost of her navy. In sum, privateering helped build up the English merchant marine, decimated that of Spain for three hundred years, and depopulated the Caribbean.41

War on the Continent

Far less profitable were the campaigns the English fought on the continent. After the Dutch became mostly Protestant in the 1560s, the Spanish tried to root out this new heresy by using the Inquisition, which with grievances about taxation provoked a revolt in 1568 that changed the nature of European warfare. Religion became the chief cause and motivation of struggles that grew increasingly brutal. Thomas Nun, a chaplain who took part in the 1596 Cadiz expedition, saw the conflict in ideological terms as an anti-papist, anti-Spanish crusade. Thomas Churchyard, the veteran Elizabethan captain, who had witnessed its horrors first-hand on the continent, called war ‘a second hell’. George Gascoigne (see ill.7), an eyewitness of the terrible Spanish sack of Antwerp in 1576, agreed that ‘war is ever the scourge of God.’42

Acting on the principle that the enemy of my enemy is my friend, in 1572 the English first sent troops to help the Dutch, their fellow Protestants.43 All the officers, and many of the other ranks, were veterans. Landing at Flushing they fought ably, killing a hundred and fifty Spaniards for a loss of fifty men. The fifteen hundred reinforcements under Sir Humphrey Gilbert did not do as well, being ambushed near Sluys and routed at South Beveland. So cowardly was the English contingent that one observer prayed, ‘God send them old beer that they may be more stabler and not to shit in their breeches and run away as often as they have done.’44

Alcohol alone could not stiffen the backs of the badly paid, wretchedly fed, woefully led and poorly supplied reinforcements. ‘I fear I must trouble my Lord Leicester and Pembroke and yourself,’ Captain Roger Williams, one of their captains, wrote to Sir Francis Walsingham in July 1582, ‘for dinner and supper. Therefore your honours may do well to speak to her majesty to give me some.’ Vittles were not forthcoming. ‘You would not believe the poverty we are in,’ Williams wrote a week later, adding in December, ‘I never saw the like misery amongst soldiers.’ No wonder some English troops vented their frustrations on their allies. ‘When drunk they can scarcely stand,’ wrote George Gascoigne of the Dutch, adding that in their country ‘whoredom is accounted Jollytie’.45

On 20 August 1585 Elizabeth signed the Treaty of Nonsuch with the Dutch Estates General, promising to send to the Netherlands 7,400 troops under Robert Dudley, first earl of Leicester, in return for the towns of Brill, Ostend and Flushing. The expedition cost nearly half of the queen's annual income. The cold, wet climate of the Low Countries wreaked an even heavier charge on the recruits. ‘Of the band that came over in August and September more than half are wasted, dead or gone, and many of the rest sick and feeble, fitter to be at home,’ wrote Thomas Digges, master-muster general to the English forces.46 Leicester admitted in July that his men were so hungry that five hundred men had deserted in the last two days: he had hanged two hundred for trying to board ship for England.47 The sick furloughed home fared badly. Packed two to three hundred on the cold floors of parish churches, one observer described them as ‘miserable and pitiful ghosts, or rather shadows of men’.48

After this inauspicious start, the English contribution to the Dutch war effort became more effective. Their numbers averaged six thousand men a year; supplies and pay improved; the quality of recruits got better. By the end of Elizabeth's reign, small but first-rate forces under captains such as Sir Francis Vere became increasingly integrated into the Dutch Army, where they learned the latest military tactics.49 In all, Elizabeth's intervention ensured Dutch independence.

To help the Protestant Henri IV of France, who was also fighting Philip II, Elizabeth sent an expeditionary force to Brittany in 1589 and another to Normandy two years later. After destroying a Spanish army of three thousand men in Brittany, Elizabeth sent four thousand men (again, mostly conscripts) to Rouen under Essex and Sir Roger Williams. The siege began in September 1591. The fighting was callous. ‘The continual burnings of the houses are great and pitiful to behold,’ recalled Sir Thomas Coningsby.50 The fires got out of control, exploding an ammunition dump, destroying two churches and two hundred houses. Within a month the siege had halved the number of fit English troops. Compared to the help the English gave Protestants in the Low Countries, the assistance rendered to them in France was of little value, especially after Henri IV converted to Rome in 1593.

Henry VIII's break with Rome in 1533, and the subsequent Reformation, fundamentally changed the nature of Anglo-Irish relations until—some might say—even today. Ireland remained a Catholic country, which over the next half century thanks to the Counter-Reformation, became even more attached to Rome, as the English grew increasingly Protestant. Sectarian and ethnic differences made war between England and Ireland even more brutal. ‘Withdraw the sword,’ warned John Hooker, who fought against the Irish, ‘and as the dog to his vomit, and the sow to her dirt and puddle, they will return to their old and former insolency, rebellion and disobedience.’51

The English viewed Ireland much as modern Americans were to deem Cuba—as an alien threat a few miles from their shores. In 1561 Sir Christopher Hatton called Ireland ‘a postern gate through which those bent on the destruction of this country might enter’. More pithily the Jesuit Father Wolf told Philip II of Spain, ‘he that England would win, let him in Ireland begin’. Tudor Englishmen were convinced that the loss of Ireland would have a domino effect that Sir William Fitzwilliam, the Lord Deputy, explained, ‘would no doubt shake this whole state’.52 Because Catholicism helped the Irish develop a rudimentary sense of nationalism, conflict there gradually became less a revolt or even a rebellion, and more a struggle for independence, even a war of national liberation. ‘The rebels stand not as heretofore upon terms of oppression and country grievance,’ recognized the Queen's Council in Dublin in 1597, ‘but for the restoring of the Romanist religion, and to cast off England's laws and government.’53

During Elizabeth's reign, war in Ireland was an almost continuous dirge of raids, ambushes and atrocities. Four main campaigns, however, stand out.

In the first, the rebellion of Shane O'Neill (1560–67), two contestants for the earldom of Tyrone fought each other. Shane waged a long and bitter war, mainly in Ulster against the English, as well as against rival Irish chiefs, before being murdered by Scottish settlers, based in Country Antrim, with whom he had sought sanctuary.

The second campaign, the First Desmond Rebellion in Munster (1569–73), began when Sir Henry Sidney, the English Lord Deputy of Ireland, arrested Gerald Fitzgerald, fourteenth earl of Desmond, for exploiting Munster, and had him imprisoned in the Tower of London. Understandably, this provoked a revolt led by James Fitzmaurice Fitzgerald which the English brutally suppressed. The rebellion ended when the queen released Desmond from the Tower.

The third campaign, the Second Desmond Rebellion (1579–83), started when James Fitzmaurice Fitzgerald landed in Ireland with a thousand troops raised by the Pope. After they surrendered the next year at Smerwick, Earl Grey de Wilton's troops slew them in cold blood. Gerald Fitzgerald, the earl of Desmond escaped, and after leading a guerrilla campaign for three years, was murdered by the Clan Moriarty for an English reward of £1,000. His head was sent to the queen, and his body displayed in triumph on the walls of Cork Castle.

The last campaign, the Tyrone Rebellion (1594–1603), was the most significant, largely because it was fought in the context of the wider naval and continental conflict against Spain.54 By 1594 Hugh O'Neill, second earl of Tyrone, had raised six thousand well-trained troops, for whom the thousand or so men the English had at Dublin were no match. Tyrone used his men to fight a guerrilla war. Exasperated, the English sent fifteen hundred men under Sir Henry Bagenal to relieve Blackwater Fort. Tyrone ambushed them at Yellow Ford, killing their commander and most of his troops. It was the worst defeat the English ever suffered in Ireland.

To ensure it was not repeated, the queen sent her favourite, Essex, to wage what one member of the privy council warned would be ‘the longest, most chargeable, and most dangerous war’.55 He landed in Dublin in April 1599 with the largest and best equipped army yet dispatched across the Irish Sea. Essex was a proven commander. ‘By your own experience in the service of the Low Countries, Portugal and France,’ grovelled Matthew Sutcliffe in the dedication to The Practice, Proceedings, and Lawes of Armes (1593), ‘you both understand the practice of arms and the wants of soldiers.’ Essex was so confident that he boasted, ‘An army well chosen of 3,000 is able for numbers to undertake any action or fight with any army in the world.’56 But instead of obeying Elizabeth's orders to invade Ulster, the bedrock of Tyrone's support, he marched around Munster before negotiating with the rebel earl. Stung by harsh reprimands from the queen, in September Essex absented his post without leave and rushed back to the court to throw himself on the queen's mercy. (It was not forthcoming, and seventeen months later Essex was executed for leading an abortive rebellion.)

The earl's folly proved a blessing in disguise because it led to the appointment of Charles Blount, Lord Mountjoy. Born in 1563, he had seen considerable action in the Low Countries and Brittany before succeeding Essex as commander of English forces in Ireland. Even though Essex opposed the appointment, telling the Privy Council that Mountjoy was ‘too much drowned in book learning’, he proved a highly practical general.57 Before his appointment, a contemporary complained that English captains had loafed ‘in great towns, feasting, banqueting and carousing with their dames’.58 Now Mountjoy had them campaign throughout the winter, clearing vegetation from the edges of roads to thwart ambushes. He established a series of garrisons and waged several simultaneous offensives, provisioning his forces from ships, as he cut Ulster, the rebel heartland, in half. Because his soldiers were not crammed in barracks where germs easily spread, but were out in the fresh—albeit cold and wet—air, disease rates fell. To deny the enemy supplies he used a scorched-earth policy. Captain William Mostyn observed that Mountjoy beat the Irish ‘by the cruelty of famine’.59 Tyrone countered by improving the training and weapons of his troops, and sought help from Spain. But the landing of four thousand Spanish soldiers in Kinsale in September 1601 could not save Tyrone. After the Spanish capitulated the following January, the English murdered twelve hundred wounded prisoners (most of whom were Irish), and then they pursued eight hundred enemy survivors for two miles after which, one participant wrote home, the chase ‘was left off, our men being tired with killing’. By the morrow the English had recovered their energies, hanging all the prisoners they could find. Three months later Tyrone surrendered.60 He died an exile in Rome in 1619, still plotting to return to Ireland.

For many Englishmen service in Ireland was a fate worse than death. As a contemporary proverb maintained, ‘better to be hanged at home than die like dogs in Ireland’.61 Recruits were cruelly neglected. ‘Many of his soldiers die wretchedly and woefully at Dublin, some whose feet and legs rotted off for want of shoes,’ a government report noted of Sir Thomas North's company, adding ‘yet were their names retained for the muster-roll.’62 Of four thousand men sent to garrison Derry in 1566, only fifteen hundred were fit for duty after seven months: the town, a captain observed, was more ‘a grave than a garrison’. The majority died from dysentery, a disease that did not ravage the native Irish, perhaps as Fynes Moryson, Mountjoy's secretary, suggested, because they drank locally distilled whiskey.63

As the Irish wars escalated, more and more conscripts were called up. On arriving at embarkation ports, they might mutiny rather than board ship. There were four mutinies at Chester, two in Bristol and London, and one each in Towcester and Ipswich. In the capital provost marshals were authorized ‘to execute summary justice’.64 In Bristol the mayor tried the ringleaders of one group, and sentenced them to be hanged before pardoning them on the gallows. Instead of thanking him for his efforts, the following year the Privy Council reprimanded the mayor for providing rations for those about to be shipped to Ireland: the food would be wasted: seasick conscripts would only puke it up. ‘There was never beheld such strange creatures,’ reported Bristol's authorities two years later, ‘most of them either lame, diseased boys, or common rogues. Few of them have any clothes: small weak starved bodies, taken up in farms, market place and highways, to supply the place of better men kept at home.’65

At least the English saw these pathetic pressed men as men, unlike the Irish whom they thought of as subhumans (in much the same way as Germans in the Second World War thought of Jews as Untermenschen who could be exterminated without compunction). As Edmund Tremayne told the queen in his ‘Notes on Ireland’ (1571), the Irish were ‘neither Papists or Protestants but rather such as have neither fear nor love of God in their hearts’: thus there was no point in trying to win either their hearts or minds, or even treating them as fellow Christians.66 Even their allies agreed: a Spanish Catholic officer who fought at Kinsale contended that the Irish were so base that he doubted whether Christ's death on the Cross was enough to redeem them. The English view that the Irish were not really human came down from the very top. Sometimes orders to kill were clouded by euphemisms. Captain George Flower was instructed to take a company to Bantry and to ‘use all hostile prosecution upon the persons of the people as in such case of rebellion is accustomed’.67 According to Edmund Spenser, his mentor, Lord Arthur Grey, the Lord Deputy of Ireland, regarded ‘the life of Her Majesties [Irish] subjects no more than dogs’.68 He boasted of having executed fifteen hundred leading Irishmen, not counting ‘those of meaner sort’.69 The English thought Irish women behaved like whores. They went about bareheaded—as did prostitutes back home. Fynes Moryson reported seeing Irish women urinate in mixed company, and then ‘Wash their hands in cow dung.’ Worse, the sluts would grind corn stark naked, pushing into the bread sacks any flour that had stuck ‘upon their bellies, thighs or more unseemly parts’.70 The English even accused the Irish of cannibalism. It was said that old women would light fires to attract cold starving orphans so they could eat them. Surgeon William Farmer described how Sir Arthur Chichester, whilst campaigning during the Tyrone Rebellion, came across five orphans who were devouring their mother, whom they had just roasted. After they explained that the English had stolen all their food, Chichester gave them vittles as well as money.71

Such generosity was rare: over the centuries far too many atrocities have blighted Anglo-Irish relations. In their attempt to conquer Ireland the Normans committed butcheries. For instance, in 1170 they executed seventy prisoners of war, throwing their bodies off a cliff, and fifteen years later sent the heads of a hundred rebels killed in Meath as booty to Dublin.72 Through their casual cruelty the outrages of early modern Anglo-Irish wars remind one of the worst excesses of the Russian Front or the Pacific Campaign in the 1940s.73 Some atrocities were committed in hot blood, making them more understandable, perhaps even excusable. In May 1567 at the Battle of Farsetmore, Donegal, an observer recalled that both sides ‘proceeded to strike, mangle, slaughter and cut down one another’.74 After the garrison of Dunboyne Castle surrendered in 1602, they were all hanged: eighty of them—men, women and boys—jam-packed from a fifteen-foot wooden beam, there being no convenient trees nearby.75

Most cold-blooded atrocities were committed during what we would today call ‘search and destroy’ missions. Essex sent a patrol to punish Con Mackmilog who had killed thirty-five English settlers; the body of one he had boiled and fed to his dogs. The English repaid in like kind, by roasting Mackmilog to use him as dog food.76 In 1597 Sir William Russell led a force through Glann-malhur, ‘killing all that came in their way’, and personally rewarded a sergeant who brought him an Irishman's head.77 Three years later, Sergeant Major George Flower reported that near Cork his column ‘got the heads of thirty seven notorious rebels beside others of less note’.78 ‘We have killed, burned, and spoiled all along the Lough,’ Sir Arthur Chichester gloated to Mountjoy in May 1601, ‘we have killed about a hundred people of all sorts, besides such as were burnt, how many I know not. We spare none of what quality or sex soever, and it has bred much terror in the people.’79 Rather than rustle cattle, Captain Anthony Hungerford and Lieutenant Parker of the Leinster garrisons ‘preferred to have some killing’ and ‘slew many churls, women and children’.

There was a rational justification for what was in effect English state-sponsored terrorism. Thomas Churchyard defended Sir Humphrey Gilbert's practice of forcing those who came to his tent to surrender to walk though a gauntlet of the heads of dead rebels by observing ‘there was much blood saved through the terror.’80

Most atrocities, however, were the product of the nature of the war. As we have seen, the English dehumanized the enemy, making them easier to kill. The war, a vicious guerrilla struggle fought among wasteland and bogs, often in terrible rainy and chilly weather, made soldiers angry, ready to vent their spleen on the enemy or even on innocent civilians. Most English soldiers were draftees, ill-fed and equipped, often sick, usually cold and wet. They hated being in Ireland, and thus hated its inhabitants. Moreover, they did not see the Irish as real soldiers who fought fair. ‘The Wars here is most painful,’ remonstrated Captain John Zouch. ‘We shall never fight with them unless they have a will to fight with us.’81 Sir John Harrington, the political theorist, agreed, complaining that the Irish led the English in ‘a Morris dance, by their tripping after their bagpipes, than any soldier-like exercise’. For much of the queen's reign Ireland was under martial law, so there were no legal limits on soldiers’ behaviour.82 Certainly officers did little to curb abuses. Anyway, asserted English commanders, the Irish were just as bad. In 1585 in County Antrim the Irish killed a thousand Scots soldiers and as many of their women and children as they could, so they were only getting their just deserts. As a final solution to the Irish problem Captain Barnaby Rich advocated castrating all the males, while Edmund Spenser, normally the kindest of men, preferred starving them to death. As he avowed in The Faerie Queene, Ireland could be civilized only through violence. Both Rich and Sir John Davies the Attorney General for Ireland, agreed that Ireland was ‘A barbarous country [that] must first be broken by war before it will be capable of good government.’83

The Costs of War

Military statistics are notoriously hard to estimate. For instance, after the First Gulf War of 1992 the Pentagon, having used aerial photographs, electronic intercepts, computers, grave registration teams, newspaper and combat reports, had to admit that its estimate of enemy casualties was plus or minus 50 per cent. Estimates for early modern war are even more problematic. They can be given in vague terms such as ‘few’, ‘many’, or ‘several thousand’. Or else an attempt can be made to use surviving evidence and the work of other analysts to come to a logical conclusion, while admitting to the weakness of the process. Because this is the way military intelligence officers work, it may be used by military historians.84

Estimates of the number of English and Welsh men who saw foreign service during the last third of Elizabeth's reign vary, being based on incomplete records.85 We know from pretty good sources that between 1594 and 1602, 42,558 soldiers left English ports for Ireland—half of them from Chester. This figure does not include the large number of those who deserted before they arrived at the ports, nor those volunteers who made their own way to Ireland, but it does count veterans returning for additional tours of duty. Estimates of the total number of English and Welsh who actually served in Ireland range from thirty thousand to thirty-seven thousand. Because the total number of English troops in Ireland peaked at twenty thousand in 1593–1603, the top end of the range seems more likely and has thus been used.86

The most recent assessment of those who saw service on the continent is by David Trim, who estimates that between 1585 and 1603 the crown recruited 80,525 men for service there. If we reduce this figure by 10 per cent to take into account fictional soldiers listed on the roster for profit, known as ‘dead pays’, we get 72,472. In addition, according to Dr Trim, 48,066 men served mostly for the Dutch while a few fought for the Huguenots, neither of whom permitted ‘dead pays’. In 1586, 68 per cent of the infantry in the Dutch Army were British.87

At sea perhaps forty thousand sailed in the Royal Navy, including 15,925 who took part in the Armada.88 On average a hundred and fifty privateering ships with, say, an average crew of fifty left British ports each year between 1585 and 1603, giving a total of 135,000 men. Of course, the majority of these were veterans, many of them from the Royal Navy, discharged after the Armada of 1588, but assuming that a quarter were not, then it would mean that 33,750 served solely as privateers. This gives us a total of 73,750 with service at sea.89

The figures for land service in England are even more problematic. During the Armada campaign 90,000 served in the trained bands, 200,000 in the militia and another 16,000 in private feudal levies giving a total of 306,000. Duplications for domestic service are impossible to obtain. Many of those who served in the militia also served in other capacities at different times. A few of the trained bands actually fought overseas. On the other hand, since the figures for domestic service are for 1588, they do not take into account men who served and left before that date, or joined afterwards. Thus it would not be unreasonable to assume—for want of better data—that these figures balanced each other out, and that 306,000 men saw domestic service. Totals for military service in the last third of Elizabeth's reign are given in Table 1 below.

What do these rough estimates mean in terms of the proportion of men who served in the armed forces? At the end of Elizabeth's reign England had a population of 3.9 million, of whom about 975,000 were males aged 18–39. Of this military pool 23.7 per cent saw foreign service and 31.9 per cent domestic service, making a total of 55.6 per cent with some military service. While these figures are advanced with a fair degree of trepidation, I can take comfort in the fact that they support Shakespeare's contention that military service was one of the ‘seven ages of man’. It was not, to be sure, as universal as ‘mewling infancy’, ‘creeping schoolward’, or old age ‘sans everything’, but some sort of military service was a stage through which over half of the Bard's compatriots passed.90

| Foreign | Numbers | Death rate | Deaths |

|---|---|---|---|

| Irish Service | 37,000 | 50% | 18,500 |

| Continent, royal | 72,472 | 37.5% | 27,177 |

| Dutch/Huguenot | 48,066 | 37.5% | 18,025 |

| Royal Navy | 40,000 | 33.3% | 13,333 |

| Privateers | 33,750 | 33.3% | 11,250 |

| Total | 231,288 | 88,285 | |

| Domestic | |||

| Trained bands | 90,000 | 3% | 2,700 |

| Militia | 200,000 | 2% | 4,000 |

| Feudal levies | 16,000 | 2% | 360 |

| Total | 306,000 | 7,060 | |

| Total foreign and domestic | 537,288 | 95,345 | |

Whatever the real figures may be for the late sixteenth century—and we will never know for sure—one thing is certain. A huge number of people, English, Welsh, Scots and Irish, men, women and children, took part and suffered in the wars of the last third of Elizabeth's reign. How many of them died? Again there are only hints. During the Cadiz expedition of 1596, disease killed 114 of Dreadnought's three hundred crew, leaving but eighteen fit enough to dock the ship when it returned to Plymouth.91 In 1574 John Lingham listed the names of seventy-four English officers killed fighting in the Low Countries. Of a sample of 475 captains who served in Ireland, 65 (13.7 per cent) died in combat and 50 (10.5 per cent) were severely wounded; no figures have survived for those who perished of disease. Fifty-five English captains died serving the Dutch. Hiram Morgan suggests that at least fifty thousand, and perhaps as many as a hundred thousand, perished in Elizabeth's Irish Wars—most of them Irish.92 Among soldiers death from disease was ubiquitous, running as high as 50 per cent a year. Edmund Spenser, the poet who fought in Ireland as a young man, noted in 1580 that of every thousand ‘lusty able men’ who came to Ireland, half were dead from disease or poor food within six months.93 Sir John Smythe alleged that only one in forty of Essex's sick troops evacuated to England survived, so bad was their medical care. Fifteen thousand set out in the ‘counter armada’ of 1589; six thousand returned. The three thousand men whom Sir John Norris took to Brittany in 1591 required eight thousand replacements over the next three years, while the four thousand troops who landed in Normandy with the earl of Essex in 1591 needed ten thousand replacements over two years.94 After seven months only six hundred of the eleven hundred men sent to Derry in 1566 were still alive, and a quarter of the four hundred sick were not expected to survive. In three months campaigning in Ireland, Essex lost between 12,175 and 17,300 men.95

We can make better sense of these episodic figures by estimating death rates and applying them to the totals given in Table 1 above. The results are summarized in the centre and right-hand columns.

Ireland was an especially lethal place in which to serve, so a 50 per cent death rate seems reasonable to apply to the thirty-seven thousand men who soldiered there. When Lord Mountjoy estimated in 1601 that three-quarters of the Irish who left to fight as mercenaries would never return home, he was including those who died or settled overseas.96 If we assume that half of these Irish mercenaries died, we get a 37.5 per cent death rate. Applied to the 72,472 men who served on the continent in the queen's service and the 48,066 who fought there as Dutch or Huguenot mercenaries, this gives us 27,177 and 18,025 dead respectively—a total of 45,202 who perished on the continent. This death rate of 37.5 per cent seems reasonable, since Professor Rodger posits that a third of those who served at sea died.97 So when this proportion is applied to Royal Navy sailors and privateers, we get 13,333 and 11,250 dead respectively, a total of 24,583 who perished at sea. Home service on land was far safer, with perhaps a 2 per cent rate for the militia and 3 per cent for the trained bands (who tended to serve longer), and for feudal levies. Table 1 suggests that in late Elizabethan England, 95,345 died directly or indirectly as a result of military service. This is 10.2 per cent of the military pool, or 2.44 per cent of the total population. In contrast 2.59 per cent of the total population died as a result of the First World War and 0.94 per cent as a result of the Second.98

Because governments are more concerned about their money than about young men's lives, better data exist on the financial costs of Elizabeth's wars. Between 1588 and 1605 England spent roughly £4,500,000 on defence, about £300,000 a year. About £1,700,000 went on the navy. Before 1580 naval expenditures averaged about £17,000 a year. In 1588, the year of the Armada, they reached £150,057, dropping to £31,050 in 1591, before peaking at £157,602 in 1598. The conquest of Ireland was even more expensive. According to the accounts of Sir Julius Caesar, James I's Under-Treasurer of the Exchequer, £1,845,696 was spent there from October 1595 to March 1603, which would agree with a recent estimate of £1,924,000 from 1594 to 1603.99 This would make the estimate of Lord Treasurer Lionel Cranfield, earl of Middlesex, that over three million pounds were spent conquering Ireland too high. War on the continent, which required sophisticated equipment, was even more expensive. In 1588 Thomas Digges, Muster Master General of English forces in the Low Countries, reported that the annual cost of an infantry company was £1,686 10s. 3d.; of a cavalry troop, £3,700; and of an artillery train, £68,396 18s.100 No wonder the queen complained that the war in the Netherlands was ‘a sieve that spends as it receives’.101 Corruption added to Her Majesty's costs. Half of the two thousand men on the rolls of the Connaught garrison in 1597 were dead pays.102 But this was small change compared to the peculations of some of the queen's ministers. Three out of her seven Treasurers at War were infamously corrupt. One, Sir George Carey, embezzled £150,000 in eight years, in addition to the 40,000 ducats he supposedly looted during the 1596 Cadiz expedition.103 According to Fynes Moryson, Mountjoy's secretary (and thus a highly reliable source), the queen ‘was incredibly abused’ by the mendacity of the generals who fought for her in Ireland.104

A Military Culture

Considering the time and effort, the blood and money that England spent on war in the last third of Elizabeth's reign, it is not surprising that, as J. S. Nolan has put it, ‘The Militarization of the Elizabethan State’ took place.105 The change was so profound that some have—incorrectly—called it ‘a military revolution’.106 Nowhere was the growth of a military culture more obvious than on the stage, particularly when compared to painting or woodcuts, where, unlike on the continent, military themes were rare.107 There were sixteen battle scenes in the thirteen extant plays the Queen's Men put on during the 1580s and 1590s. Shakespeare's Henry V, perhaps the greatest war play ever, was written and performed during the spring of 1599, when Essex was preparing to invade Ireland.108 Shakespeare, Middleton, Marlowe, Jonson, Beaumont and Fletcher all knew that war—like patriotism—sold tickets. Christopher Marlowe is said to have used Instructions for the Warres by Raimond Fourquevaux, the French soldier and diplomat, in writing Tamburlaine. In his play, The Famous Chronicle of Edward the First (1593), George Peale has the Queen Mother boast:109

What warlike nation, trained in feats of arms

What barbarous people, stubborn and untam'd …

Erst have not quak'd and trembled at the name

Of Britain?

Stage effects—the louder the better—could bring down the house, both figuratively and literally. Crowds flocked to the theatre to see and hear them. Plays became so violent, noisy and dangerous that a 1574 proclamation condemned the ‘sundry slaughter and mayhemmings of the Queen's subjects’ caused ‘by engines, weapons, and powder in plays’.110 Such concerns about the audience's safety were not groundless. During a 1594 performance at the Rose Theatre (probably of Marlowe's Tamburlaine), an actor fired a musket that he believed was unloaded, and accidently killed a child and pregnant woman in the audience.111 In 1613, during a performance of Shakespeare's Henry VIII, pyrotechnics set fire to the thatch roof, burning the Globe down to the ground in two hours.

No playwright portrayed war better than Shakespeare. So good was he that Duff Cooper, biographer and Conservative politician, argued (without a shred of evidence and with more than a scintilla of snobbery) that the Bard must have fought with Leicester on the continent as a sergeant, the provincial lad from Stratford-upon-Avon not being well-born enough to be an officer! Shakespeare must have talked to soldiers, and read their memoirs. For instance, he lifted the plot for Twelfth Night from Barnaby Rich's Riche: His Farewell to Militarie Profession (1581).112

War made good comedy. From Shakespeare's Falstaff to television's Dad's Army, England's civilian soldiers have been portrayed, at best, as figures of fun or, at worst, to quote Barnaby Rich, ‘Drunkards and such other ill disposed persons’.113 The recruiting scenes in both parts of Henry IV are hilarious, although one suspects that Thomas Mulsho, a gentleman from Northamptonshire, would not have enjoyed them. In the summer of 1597 (at about the same time as Shakespeare was writing the play), Mulsho complained to a friend how hard it was to fulfil his quota, twenty of his draft from Finedon having run away before the recruiting officer could interview them. ‘I am at my wit's end,’ Mulsho concluded.114

An indication of the impact of Shakespeare's portrayal of war was that years after his death in 1616, soldiers on active duty repeated the rhythms and themes of his plays. In the dedicatory verses to The Master Gunner (1625) Captain John Smith wrote ‘All the world is but a martial stage’, while in the text Robert Norton observed that England was ‘strongly situated by nature, entrenched with a broad dike’. Fourteen years later, as he crossed the River Tweed at the start of the First Bishops’ War, Sir John Suckling, the poet, recalled Henry IV, Part I, written ‘by My Friend Mr. William Shakespeare’. The outbreak of the Civil War reminded Robert, the third earl of Essex, of Hotspur's soliloquy on the dangers of rebellion. (The Bard's eloquence was not enough, however, to stop the earl from accepting command of the rebel army.) ‘We are both on a stage,’ Sir Ralph Hopton, the royalist general, wrote to his friend Sir William Waller, the parliamentary commander, after the Civil War broke out, ‘and must act out the parts which are assigned to us in this tragedy.’115

The popularity of war on the stage was matched by that of military manuals, sixty-six of which were published in Elizabeth's reign.116 Obviously the main purpose of such manuals was to train troops, a subject discussed in Chapter 2. But they also shed light on the military culture. No self-help manuals, not even those on religion, sold better than those on war. For instance, Matthew Sutcliffe's The Practice, Proceedings and Lawes of Armes (1593), it was claimed, sold 1,200 copies in eight days.117 Such sales reflected a growth in the general market for books caused by the expansion of the universities and inns of court, as well as the doubling of the literacy rate for the yeomanry. Yet readers purchased military manuals for the same reason that people today read military history and novels, or watch war films or the History Channel. As Edmund Plumme wrote in his introduction to Robert Ward's Animadversions of Warre (1639), ‘Here may you fight by Book, and never bleed.’ Such works naturally appealed to young male readers. ‘I ever from my tender years have delighted to hear histories read that did treat of actions and deeds of arms,’ recalled Sir John Smythe, adding that as an undergraduate at Oxford, ‘I gave myself up to the reading of many other histories and books treating of matters of war.’118

The healthy market for military books then—as now—attracted professional authors. For professional soldiers writing frequently posed a challenge. Confessing that he was an ‘unlettered man’, Geoffrey Gates had a ghostwriter pen The Defence of the Militarie Profession in 1579.119 All too often, hacks copied from each other, or slavishly repeated the mantras of classical writers. There was ‘not a more distasteful sound’, wrote Francis Markham (who claimed thirty years’ military experience), than listening to so-called ‘book soldiers’, who asserted they were experts on war, even though they had never heard a shot fired in anger.120 In The Fruits of Long Experience (1604) Barnaby Rich likened them to ‘women's tailors’, who ‘can devise every day a new fashion’. Shakespeare dismissed pundits who wrote ‘bookish theoric’ as producing ‘mere prattle without practice’, and scorned those authors (such as himself) who had121

Never set a squadron in the field

Nor the division of a battle knows

More than a spinster.

The venom of such attacks on book soldiers may well have been the product of the paradoxes inherent in writing about war. If an amateur wrote about war without first-hand knowledge, or slavishly followed classical precedents, and got it wrong, then men could lose their lives. Because war is so loathsome and may attract ‘the scum of the earth’, some assumed that military authors were just as bad. In The Solace for the Souldier and Sailour (1591) Simon Harward, a military chaplain with combat experience, wrote that soldiers lived a ‘most wicked and dissolute life’. The same year Sir William Garrard's The Arte of Warre called ‘the profession of arms a vile and damnable occupation’. William Cecil, Lord Burghley, arguably the most powerful peer of his time, told his son that a member of the military profession ‘can hardly be an honest man or a good Christian’.122 A few writers countered such criticisms by arguing that war was divinely ordained. John Elliot, the translator of Bertrand de Loque's Discourses of Warre (1591), claimed it was ‘grounded on God's Holy word’.123 Just as God ‘hath appointed Life and Death, Summer and Winter, Day and Night,’ wrote James Achesone in The Military Garden: or Instructions for all Young Soldiers (1629), ‘so hath he made Peace and War.’ Sometimes military men countered attacks on their profession by adopting such a high moral tone that they appeared ridiculous. ‘Serve God daily, love one another, preserve your vittles, beware of fire, and keep good company,’ commanded Sir John Hawkins's standing orders for his 1562 slaving expedition. No wonder, on reading them, Queen Elizabeth sniffed, ‘God's Death! This fool went out a soldier and came home a divine.’124

The second paradox concerning war was that soldiers and sailors were conservative folk, who plied their trade in the hierarchical and deferential society of Tudor England. They studied past wars to win future ones. In their manuals writers such as Barnaby Rich, Thomas Proctor, Thomas Digges, Edward Hobby, John Smythe and Thomas Styward looked back to Greece and Rome for inspiration as well as legitimacy. At sea Sir Francis Drake compared his 1587 attack on Cadiz to Hannibal's achievements.125 Yet war is usually won by the side with the latest technology and methods. ‘Through mutation of time, and invention of man's wits the practice of war changes,’ noted Henry Barret in 1549. A generation later Thomas Lodge agreed: ‘All things change, the means, the men, the arms. Our strategies now differ from the old.’126 When a gentleman praised the old ways of fighting, Robert Barret reproved him in 1598: ‘Sir, that was then and now is now.’ The art of war had ‘greatly altered, the which we must follow,’ wrote Captain Roger Williams, ‘Otherwise we must repent it too late.’127

Like modern social scientists, military writers and practitioners tried to define war as a science with its own theoretical and historical foundations—what Captain Fluellen in Henry V called ‘the disciplines of the war’.128 ‘It is not only Experience and Practice which maketh a soldier,’ wrote ‘Captain J. S.’ in his Military Discipline and Practice, or the Art of War (1589), ‘but the knowledge most specially learned by reading History.’129

The officer corps was growing not just in expertise but in size. Whereas in 1569 there was hardly a captain ready to train the militia, within nineteen years there were at least two hundred available, all veterans of the Irish and continental wars. ‘The place of the captain is not lightly to be considered,’ wrote Giles Clayton in The Approved order of Martial Discipline (1591), ‘for that upon his skill and knowledge depends the safety or loss of men's lives.’ The—quite literally—vital need for skill and knowledge of war from self-made captains in a society that during peace valued birth and hierarchy, produced conflicts between civilians and those whom Professor Manning has called ‘the swordsmen’.130 Humphrey Barwick's experience at the Siege of Leith in 1560 illustrates these tensions. Having joined the army as a private, through hard work and merit Barwick became a captain in twelve years. During the siege he suggested to the future Lord Grey de Wilton ‘in a courteous manner’ that he had sited his camp in a dangerous position. ‘Whereat he seemed to be offended,’ telling him to mind his own business. Soon afterwards the Scots attacked: Grey was wounded and his men were routed—much to Barwick's schadenfreude.131

Notwithstanding the claims of old soldiers, such as Francis Markham, that ‘the fittest man to make a soldier is a perfect gentleman’, most officers did not enjoy great social prestige.132 The percentage of peers with military experience fell from 75 per cent in Henry VIII's reign to 25 per cent in Elizabeth's. The well-born who did serve were sometimes too arrogant or careless to take the proper professional precautions. Because Sir Philip Sidney refused to wear his armour, he died in great agony at Zutphen in 1586 three weeks after a musket bullet shattered his thigh bone.133 Thomas Moffett, who had fought with Sidney and Essex (two other puissant peers), once rhetorically asked whether the sprigs of the nobility were ‘the sons of Mars’. ‘Nay, the nephews of Venus,’ was his answer.134 No wonder Humphrey Barwick, who in 1594 described himself a ‘Gentleman, Soldier, Captain’, sardonically observed that ‘it is better for a man to be accounted a good soldier in the court than to be the best soldier in the field.’135

The queen was ambivalent towards soldiers. Personally she was very attached to John and Edward Norris, and Peregrine Bertie, baron Willoughby, adding notes to them in her own hand to state letters. She was fond of—some say in love with—Leicester, was infatuated with Essex, and charmed by swashbucklers such as Raleigh. But at the same time she resented those military men who used her purse to prove their masculinity. While Essex might boast that ‘No nation breeds a warmer blood for war’ than the English, Elizabeth was the one who footed the bill both financially and politically. So she forbad the London printers on pain of death from publishing pamphlets that Essex had hacks scribble glorifying his achievements during the Cadiz expedition.136 Occasionally, Elizabeth sympathized with the rank and file. ‘It frets me not a little that the poor soldiers who hourly venture life shall want their due,’ she wrote to Leicester on 19 July 1587.137 More common was the view she once expressed to the French ambassador that soldiers were ‘but thieves and ought to hang’.138 Soldiers filched her money, either through embezzlement or strident demands. They were uncouth. When Captain Roger Williams was allowed into court to present a claim for back pay, the queen, tiring of his arguments, cut him off. ‘Faugh, Williams, I prithee thee be gone. Thy boots stink.’

‘Tut, madam, tis my suit that stinks,’ the old soldier replied.139

After the queen's death, Sir Walter Raleigh (who had sense enough not to do so while she was alive) grumbled that if Elizabeth had ‘believed her men of war as she did her scribes’, England would have thrashed Spain. ‘But Her Majesty did all by halves.’140 Later historians and warriors have agreed. Sir John Fortescue said she did not like soldiers and treated them badly. Field Marshal Montgomery thought that ‘England's part in the history of land war in the sixteenth century was practically nil’. According to G. R. Elton the cost of war was as monumental as its benefits were meagre. He blamed the queen, who ‘displayed qualities of indecisiveness, procrastination, variability of mind, cheeseparing that went far to ensure the failure of the various enterprises attempted’.141

Recently, such negative views of the last third of Elizabeth's reign have been challenged.142 During these years England beat the Spanish, completed the conquest of Ireland, and, by helping the Dutch win independence, may well have ensured the survival of Protestantism. Englishmen recognized that the Royal Navy dominated the seas and the implications of seapower. ‘Whosoever commands the sea commands the trade,’ wrote Raleigh, ‘whosoever commands the trade of the world commands the riches of the world, and consequently the world itself.’143 Elizabeth not only laid the foundations of English hegemony, but did so remarkably cheaply—at least in comparative terms. To be sure, the £4.5 million–5.5 million that England spent on war in the last third of the queen's reign was no paltry sum. Yet it represented just 3–4 per cent of its Gross National Product, as compared to the 8–9 per cent the Spanish and the 16 per cent the Netherlands expended. During the 1540s Henry VIII spent £650,000, or 260 per cent of his annual income of £250,000, on the French war; in 1600 Elizabeth spent £320,000, or 86 per cent of her annual income of £374,000, conquering Ireland. In sum, Elizabethan warfare obtained great results at a sustainable cost—something that was to elude the queen's immediate successors.