They have a king and officers of sorts;

Where some, like magistrates, correct at home,

Others, like merchants, venture trade abroad,

Others, like soldiers, armed in their stings,

Make boot upon the summer's velvet buds.

Henry V, I, ii, 196–203

‘I STOOD IN THE STRAND AND WATCHED IT AND BLESSED GOD,’ WROTE the diarist John Evelyn on 29 May 1660, for he, like millions of his fellow subjects, was thanking his Maker for the restoration of Charles II. Five days earlier the king had sailed from Holland aboard the Naseby (hastily rechristened the Royal Charles) and landed at Dover, ending fourteen years of exile on the continent. His journey to London was a triumph. At Dover, Canterbury, Rochester, Deptford and Southwark, commoners and the quality welcomed their new king with universal enthusiasm. So crowded was London Bridge that the king and his entourage could hardly push through into the City, where the Horse Guards and five regiments of infantry were waiting to escort him to his palace at Whitehall (see ill. 14). As Evelyn watched the soldiers, their plain russet-coats being adorned with silver cloth and lace to make them look less Cromwellian, he wryly observed that the restoration ‘had been done without one drop of blood shed and by that very army that had rebelled against him’.1

This chapter will examine the role of the armed forces from the restoration of the monarchy to the Revolution of 1688. The army got little thanks for putting Charles II back on the throne, if only because many blamed it for the crises of 1659–60 that made a restoration necessary. Distrust of a standing army remained strong. Quickly, however, it was realized that the country could not survive without one, so the practice of purchasing commissions was instituted to ensure that the officer corps was tied to the establishment and would never again be tempted to take over the government. Since the navy had largely stayed aloof from politics during the Civil Wars, it did not adopt a similar system. Indeed, reforms, such as exams, were introduced to encourage the promotion of the competent, resulting in the navy's creditable performance in the Second and Third Dutch Wars. The accession of the Catholic James II in 1685 changed everything. Initially, the army was loyal to the new king, who had a stellar military record, and crushed Monmouth's rebellion. But when James packed the army with Catholic officers, and increased the size of the armed forces, fears about a standing army increased, being one of the reasons why William and Mary were invited over from Holland to restore Protestantism. They were successful, and England was saved from another Civil War because at the crucial moment the army, led by John Churchill, changed sides.

The Restoration Army

When John Evelyn noted in his diary how the same army that had executed Charles I eleven years later restored his son to throne, he added ‘It was the Lord's doing!’2

To be fair, George Monck deserved as much—if not more—of the credit. Born in 1608, the son of Sir Thomas Monck, a member of the Devon gentry, Monck had been a professional soldier for the whole of his life. He saw action during the expeditions to Cadiz in 1625 and to Rhé two years later. In 1637, in Dutch service, Monck led the ‘Forlorn Hope’ at the Siege of Breda. In 1640 he returned to England, taking part in the Second Bishops’ War, before fighting for the king in Ireland. In 1644 soon after Monck returned to England, the parliamentarians captured him at the Battle of Nantwich, and held him prisoner in the Tower for two years. They released him to fight on their behalf in Ireland. In 1650 he went with Cromwell to Scotland, being appointed commander of a regiment, which he led with great distinction at Dunbar. After a brief secondment as one of the three sea-generals of the navy, where he fought brilliantly in the First Dutch War (1652–54), Monck returned to Scotland to crush Glencairn's Rebellion. He was widely respected by the army. Cromwell thought him an ‘honest general … a simple hearted man’.3

After Cromwell died in 1658 everything unravelled. In January 1660, at the head of an army seven thousand strong, Monck marched his troops from Coldstream, on the Scottish border, to London which he entered a month later. In March he recognized that military rule was not the solution, telling a General Council of officers that ‘nothing was more injurious to discipline than their meeting in military council to interpose in civil things’.4 So after a couple of months of growing disorder General Monck opened negotiations with the king, which were completed on 1 May.

Charles II was grateful to the man who had restored him, awarding Monck the Order of the Garter, making him earl of Albemarle, Captain General and Commander-in-Chief, giving him a pension of seven hundred pounds a year, an estate in Essex, and—as if that were not enough—much of the Carolina colony. The king was not so bountiful towards the army, which had after all executed his father and forced him into exile. Indeed, the army was most unpopular. In the summer of 1660 a ballad declared:5

Make room for a honest Red-Coat

(and that you'd say's a wonder),

The Gun and the Blade

Are his tools—and his Trade

In for pay, to kill and Plunder.

Parliament disbanded the forty thousand-strong New Model Army, paying the troops their arrears of £835,819 8s. 10d. Officers and men went quietly back to civilian life. Perhaps some roundheads had had enough of war and military service; others felt it safer to lie low in case they attracted the attention of the new regime.

The restored monarch swiftly realized that he could not remain in power without an army. In November 1660 Charles II ordered the raising of the King's Regiment of Guards (now the Grenadiers), composed mostly of men who had served him on the continent. Its commanding officer, Colonel John Russell, an ultra-royalist member of the Sealed Knot, quickly recruited twelve companies of a hundred men. The rising of the Fifth Monarchists, an extreme puritan sect, in January 1661 convinced the king that these forces were not enough. In February he reconstituted Monck's New Model Regiment as the Lord General's Regiment (later the Coldstream Guards), and formed a regiment of horse (later the Life Guards). Within two years the army increased from five thousand to eight and a half thousand regular troops. It remained that size for most of Charles's reign, falling to 6,797 men in 1680. In the 1670s the army consisted of two cavalry regiments (the Life Guards and the Horse Guards), of 1,080 troopers, three infantry units, the First Foot Guard, the Coldstreams, the Marines, and Holland's Regiment (The Buffs, or East Kent), with seven thousand men, plus another thirteen hundred in thirty garrisons.

The restoration army had two main duties, internal security and external defence.

Policing was its main internal role. The army patrolled roads to suppress highwaymen, many of them reputedly cavalier officers who could not settle down after the Civil Wars. Every month a squadron of cavalry escorted gold and silver from the Naval Office in London to Portsmouth and Chatham to pay sailors and dockyard workers. Soldiers were stationed outside London theatres before and after performances, and at Tyburn and Newgate during executions. After the government ended the practice of farming out the collection of customs to private entrepreneurs, replacing it with the Board of Customs in 1671, the army was extensively used to curb smuggling.6 In Scotland an Anglo-Scots force under the duke of Monmouth, the king's illegitimate son, dispersed a rising of Glasgow covenanters at Bothwell Bridge in 1679, massacring a couple of hundred afterwards. Soldiers do not, however, make good policemen, especially when dealing with civilians, such as the Oxford undergraduates who disdained troops as their social inferiors. In May 1678 fighting broke out between soldiers, who were billeted in student housing, and undergraduates, who were affronted that the former had attacked the proctors. Happily, this unique example of student affection for the university's police did not end in death or serious injuries.7

Within two years of coming to the throne Charles dispatched troops overseas. In 1662, as part of his marriage treaty to Catherine of Braganza, Charles agreed to send (and pay for) an expeditionary force to Portugal. A year later one of its officers, Sir Henry Bennet, wrote home that ‘The English forces … do daily molder away’ for want of pay, food and accommodation. The king used foreign service to get rid of New Model Army veterans, especially officers, who might be a threat to his regime. His plan was lethally effective. Only a fifth of the five thousand British troops sent to Portugal over the next five years returned home, while 43 per cent of Thomas Dongan's regiment (most of them roundhead veterans) sent overseas as part of the British Brigade in French service, died or deserted within two months in 1678.8

Britain's involvement with Tangier—part of Catherine's dowry—was equally ruinous in men and money. When the first military governor Henry Mordaunt, earl of Peterborough, arrived there in 1662 he found a derelict town, with no defences or harbour, being invested by several thousand Berbers. Within a few months the garrison grew to two thousand foot and five hundred horse, and work started on the defences and building a harbour wall. The Tangier Regiment (Queen's Royal West Surrey Regiment) were the first long-term garrison, being sarcastically known as ‘Kirke's lambs’ after their colonel, Percy Kirke, and his banner, a paschal lamb. Maintaining Tangier was dreadfully expensive, costing £140,000 a year in 1676. When parliament refused to vote money for the garrison, it was evacuated in 1684. In some ways the Tangier garrison anticipated future imperial bases, such as Gibraltar, Malta, Suez and Aden. It was the first one that included wives on strength, as well as a schoolmaster. But unlike later imperial bases it failed, basically because it lacked an empire to support. The restoration army had bitten off more than it could chew.

The Purchase System

With too many enemies in Tangier, the restoration army lacked friends at home. For one thing it was composed of the dregs of society, who were missed little, if at all. In 1672 someone described its recruits as ‘gaolbirds, thieves and rogues’. Six years later a letter writer called soldiers the ‘scum of our nation’.9 Lord Macaulay, the historian, described the Tangier Regiment, which returned to England after the evacuation, as ‘the rudest and most ferocious in the English army’.10

Fear and loathing of soldiers lasted for a remarkably long time. Colonel Silius Titus told the House of Commons in the 1660s that ‘In peace there is nothing for an army to subdue but Magna Carta.’ ‘There is no more disagreeable thought to the people of Great Britain,’ wrote Joseph Addison in 1708, ‘than that of a standing army.’ Daniel Defoe agreed that ‘A standing army is inconsistent with free government.’ Edmund Burke declared that a disciplined army is ‘dangerous to liberty’, just as an undisciplined one ‘is ruinous to society’. Across the Atlantic the ghost of Oliver Cromwell lurked behind the Founding Fathers as they wrote the Constitution which made a civilian, not a soldier, commander-in-chief of the armed forces.11

The English gentry preferred to keep commands in the restoration army in the hands of their own sort, men whom Charles II called ‘the most ordinary fellows that could be’.12 During the Civil War the militia and trained bands had become thoroughly professionalized: some believed too much so. Afterwards the gentry, amateur soldiers, regained command, and admittedly ran their regiments and companies with a passable efficiency. ‘Our security is the militia,’ boasted Sir Henry Capel to the House of Commons in 1673, ‘that will defend and never conquer us.’13

The problem was that a part-time militia was not strong enough to protect the nation, which anyway had a standing army several thousand that, unchecked, could once again take over the government. So unplanned and haphazardly, and in spite of many objections, a solution was found in the system of purchasing commissions.

While the origins of the purchase system may be traced back to the middle ages, it did not become widespread until after the restoration.14 In 1681 Charles II spent five thousand pounds on a colonelcy in the Grenadier Guards for his illegitimate son, Henry Fitzroy, aptly ennobled as the duke of Grafton. Four years later the king ordered that to be valid all purchases of commissions should be registered with the Paymaster General, thus recognizing and regularizing the system. Even so, Charles's closest advisers opposed the process. ‘I sell no offices,’ the earl of Clarendon boasted, ‘I wish the officers of the army did not: then there would not be so much sharking from the poor soldiers as there is.’15

In spite of such protests, the purchase system took hold for several reasons. During the commonwealth many cavalier officers had served in the French Army, reputedly the finest in Europe, where purchase was the norm. Selling a commission on retirement, death or wounding provided an officer, or his widow, with a lump sum that could be used to buy an annuity. Buying commissions reduced the pool of candidates, particularly among penurious ex-roundhead officers.

The chief attraction of purchase was that it kept army officers chosen for their merit and zeal from taking over the government as they had in the commonwealth. After the restoration the nobility and gentry were determined that the army would never again turn against them. So by making commissions available only to the wealthy, the gentry and nobility ensured that their sons—usually the younger ones—dominated the officer corps, and that the army was thus no longer a threat to the political order. The two were intimately linked. For instance between 1714 and 1769, 152 or 40 per cent of all regimental commanders were also members of parliament. Money and family connections not only enabled the aristocracy (and to a lesser extent the gentry) to control the system of military promotions at the regimental level, they also permitted them to dominate the electoral system, managing British politics until the Great Reform Bill of 1832 at least.

That a generation after the abolition of the House of Lords in 1649, the peerage was able to control British politics as well as the British Army, was an amazing comeback.16 During the middle ages, through the heavily armoured knight, the aristocracy had dominated the battlefield. The development of the longbow, and then gunpowder weapons, ended their mastery. Siege artillery, which only the crown could afford, made noble castles with their vertical stone walls far more vulnerable. By Elizabeth's reign the aristocracy had become domesticated; the view that the Civil Wars were a last desperate baronial revolt is unconvincing: certainly the men who actually fought them did not think about it in such terms.17 Yet within twenty years of a standing army becoming recognized as a necessary evil, the aristocracy and gentry had taken over the officer corps. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries 23.6 per cent of English army officers were the sons of nobles. The aristocratic grip on the system increased with each rank. Between 1660 and 1701, 38 per cent of regimental commanders were peers, while many more were their sons. By 1769 over 43 per cent of regimental and 50 per cent of garrison commanders were from aristocratic families. Of a sample of 188 officers who served from 1661 to 1685, 39 were peers or sons of peers, 73 were knights or baronets, 53 were esquires or gentlemen, 89 served in the House of Commons, 69 in the Lords—while only 18 (10.4 per cent) were of humble birth. No wonder Peter Drake, the eighteenth-century soldier of fortune, complained that the gap between officers and NCOs had widened.18

Purchase was not only an insurance that the army would never take over the establishment: it morphed into a vast system of outdoor relief for the titled classes that meshed with their gentleman's code of honour. Younger sons, debarred by primogeniture from inheriting the family estates, found a rewarding career in the infantry and cavalry. Jobs for the well-born boys increased. While a Civil War regiment of foot had approximately one officer for every sixty men, by the eighteenth century this figure had risen to one in nineteen.19

The purchase system had another, less recognized advantage. By permitting a free market, it meant that the monarch could not control who became lieutenants, captains, majors and colonels. Admittedly, the king could—and did—determine appointments to general-level commands. Had the post-restoration monarchy been able to control who became an officer, and who could buy and sell commissions, and thus be promoted, then it might (as had Charles I and the earl of Strafford in Ireland during the 1630s) have created an army whose first loyalty was to the crown.20 Such armies were the norm on the continent. Charles I had been utterly opposed to surrendering his right to appoint army officers. ‘By God, not for an hour,’ he vowed in 1642 when parliament demanded that he do so.21 And it was over this immediate issue, more than any other, that he fought a Civil War. Yet his eldest son, Charles II, always the realist, gave up this right with nary a protest: when his younger son, James II, tried to regain it, he provoked yet another revolution.

For most of the 271 years the purchase system was in place it worked reasonably well. By and large the British officer corps studied its profession, and had a sincere, if distant, regard for their men.22 Of course, having to stand in rank during battle to give and receive volleys of musket fire at a range of one to two hundred yards did not demand much intelligence from an officer. (Indeed, the lack thereof might have been a distinct advantage.) During this period casualty rates for officers were similar to other ranks (unlike the wars of the twentieth century). Between 1660 and 1871 two-thirds of commissions were purchased. The proportion declined during wars when the expansion of the army increased the demand for officers. For example, it fell to 25 per cent in 1810 at the height of the Napoleonic Wars.23

In its favour the purchase system allowed younger, and thus more vigorous, men to buy regimental command in the infantry and cavalry more quickly than in the artillery or engineers where promotion was by seniority. It may have also helped produce the ‘amateur’ tradition of the British Army. This not only prevented the officer corps from becoming a caste, set apart from civilians, but encouraged the idea, perhaps the myth, that through manly pluck the British officer played up and played the game, and by muddling through the gentlemen somehow beat the players in the last innings.24

Commissions could not be purchased in the corps of artillery and engineering, where special skills were required, but had to be earned by studying at a military academy, such as Woolwich. The scientific element of these military arms was strong. From 1661 to 1687 a tenth of the projects investigated by the Royal Society related to military sciences, mostly ballistics.25

Throughout the entire army, and not just among sappers and gunners, there was, however, a growth of standardization and professionalism. In 1675, 1,800 copies were issued to both the regular army and militia of the standard drill manual, The Abridgment of Military Discipline, which among other things ordered that all drill movements were ‘to be performed with a graceful readiness and exactness’. Further editions of the manual appeared in 1680, 1685 and 1686.26 Officers were encouraged to go abroad to study foreign armies. Many had learned much from their service as mercenaries with the Dutch and Swedes, particularly about the importance of training. For instance, at Hounslow Heath a mock fort was built to make exercises more realistic.27 In 1681 Charles II founded the Royal Hospital, Chelsea, which by 1690 housed 595 army veterans. Grenadier companies developed in each infantry battalion composed of the strongest soldiers, who carried three to four bombs in addition to their flintlocks.

To augment the distinction (in both senses of that word) of officers, gorgets were introduced after the restoration. These small plates hung around the neck over the chest mimicked the armoured breastplate worn by medieval knights. A royal warrant of 1684 ordered that ‘for the better distinction of Our officers’ captains should wear gold gorgets, lieutenants black ones studded with gold, and ensigns silver. By 1702 all gorgets had the royal coat of arms engraved upon them, underscoring the officer corps’ links with the crown.28

The adoption of uniforms, which started in the Civil Wars and became standard after the restoration, also reflected the army's growing identification with the monarchy and, more so, the state. In the past only servants had worn uniforms. Thus, when the state issued them to its soldiers it claimed them as its servants. Uniforms drew a clear distinction between the military and civilians. Uniforms have other practical advantages. They might frighten the enemy by enhancing intimidating physical attributes such as height or broad shoulders. They could enhance the wearers’ self-confidence, establish a hierarchy, reinforce unit esprit de corps, and distinguish friend from foe in the gunpowder-induced fog of battle. Red coats, some have argued, were a clever choice, since their colour masked the extent of bloody wounds, limiting panic and clinical shock. Others, perhaps more familiar with the military mind, have pointed out that red may have been selected since it was the cheapest dye on the market.29

The purchase system worked astonishingly well, helping produce both Marlborough's and Wellington's armies—perhaps the best in the history of the British Army. It lasted a remarkably long time, ending in 1871, mainly because of the monumental incompetence of the officer corps during the Crimean War (1853–56). Charging Russian artillery into the valley of death—doing and dying without reasoning why—was almost as stupid an exploit as, say, marching one's infantry company like lemmings off the edge of a cliff. While no record has been found of an army captain actually doing the latter, many a naval captain has wrecked his ship on the rocks below.

The Restoration Navy

As the Royal Navy expanded after the restoration, it managed to find ways of balancing the need for competence while ensuring that the naval officer corps remained loyal to the establishment, largely through the work of Samuel Pepys.

This new navy was a mighty and growing force, consisting of vessels owned by the crown and dedicated to military service. In the past the state had often requisitioned or chartered merchant vessels, there being little structural differences between merchant and naval ships since both carried cannon. Local coastal communities might also provide vessels for their own defence (as was the original purpose of ship money), or else the state could license privateers so entrepreneurs could seize enemy ships for profit. Privateering, legalized by letters of marque, continued to be an important adjunct to naval warfare for well over a century. But the strategic responsibility for making war at sea increasingly became the task of the Royal Navy, an indication of the crown's growing monopoly of frigates and ships of the line.30 Between 1660 and 1688 the number of Royal Naval vessels over a thousand tons increased from 88 to 132, the average size of ships growing by 40 per cent.31 They required a vast complicated support system. Naval bases were the largest industry in the land, with sophisticated operations, such as rope making, food preparation and preservation, shipbuilding and repair.

The tensions between naval officers appointed for their lineage and those for their competence went back a long way. Sir Francis Drake, it will be remembered, insisted that the gentlemen and mariners must work together, since the cruel sea was no place for the dilettante no matter how blue his blood. This was in direct contrast to the land, where pedigree counted as much if not more than proficiency. In the Royal Navy the contest between lineage and competence was seen in terms of the ‘gentlemen’ and the ‘tarpaulins’, those hoary-handed and often hoary-mannered officers who had risen by ability. The dichotomy may be simplistic. ‘Gentlemen’, wrote Nicholas Rodger, was a code word for royalist officers, just as ‘tarpaulins’ was for commonwealth ones, who had been mostly been ex-warrant officers or owner-masters from the merchant marine.32 Tarpaulins often disdained gentlemen. William Bull, the master of the Hector, who started his career as a captain's apprentice, wrote that the gentlemen knew nothing about the sea, and cared less about their crew, ‘the poor sailors being made a slave and vassal to every supposed gentlemen’.33 Gentlemen ofttimes sneered at tarpaulins as parvenus. It was said that Admiral John Benbow started life as a butcher's boy, and that Admiral Shovell had been a shoemaker's apprentice, while Pepys claimed to know four or five captains who had been footmen.34 Compared to the army, few naval officers were the sons of the nobility, especially in Scotland and Ireland. During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries 6.9 per cent of Englishmen who served as officers in the navy and 23.6 per cent in the army were from aristocratic families, as compared to 6.3 per cent and 37.5 per cent of Irish officers and 1.7 per cent and 38.3 per cent of Scots. In other words, army commissions were nearly four times more popular than navy ones among English aristocratic officers, six times more so among the Irish, and twenty-three times more so with the Scots.35

Over time the gap between tarpaulins and gentlemen narrowed. In 1665 the duke of York had Lieutenant Mansell of the Rainbow court-martialled and cashiered for reproaching his captain for having been a Cromwellian, and ordered that in future no reference be made to a man's previous service.36 The public image of the naval officer as both a competent tarpaulin and courteous gentleman developed. For instance, in William Congreve's play Love for Love (1695), Captain Ben Legend is an uncouth bluff fellow. He hails the heroine, Miss Prue, as if she were a frigate several cables away, suggesting they ‘swing in a hammock together’. Understandably, she turns him down. Fifteen years later, in Charles Shadwell's play, The Fair Quakers of Deal: or the Humours of the Navy, Captain Worthy beats Captain Flip, a ‘most ignorant Whappineer-Tar’, and Captain Mizen, ‘a cynical sea fop’, to get the girl.37 The play's hero blends both breeding and gentility, a combination that in real life owed much to Samuel Pepys. Pepys was, without doubt, the greatest English diarist. Some have suggested that his importance as such may have exaggerated his significance as a naval reformer. But there is no question that he loved the Royal Navy and its honest sailors. ‘This day,’ he wrote in his diary for 12 March 1667, ‘a poor seaman, almost starved for food, lay in our yard a-dying. I sent him half-a-crown and we ordered that his ticket [for arrears of wages] to be paid.’38

Born a London tailor's son in 1633, Pepys was a bright, ambitious boy who went to St Paul's School and then Cambridge University on scholarships. Through a connection with a distant cousin, Edward Montagu, first earl of Sandwich, he sailed as the earl's secretary to the Baltic in 1659. The following year he was aboard the fleet that went to Holland to bring Charles II back for the restoration. In July 1660 he was appointed to the Navy Board at the munificent salary of £350 per annum, starting a connection with the Admiralty that, on and off, would last twenty-nine years.

Pepys was a very hard worker, often at his desk by four in the morning. He studied every detail and constantly harked back to the good old days of Elizabeth's navy.39 In 1670 he reprimanded Sir Anthony Deane, the shipwright, for using iron braces to strengthen the Royal James, a newfangled practice that soon became the norm. By the standards of his time he was honest, despising those who were corrupt. Thus Pepys dismissed Charles II as being ‘only governed by his lust, and women and rogues’.40 He had a much higher opinion of the king's younger brother, the duke of York, with whom he worked closely to reform the navy. James wrote standing orders that defined everything from petty officers to petty discipline—'those who pisseth on the deck’ were to receive ten lashes.41 So when James complained that there were no clear job descriptions for the Navy Office, Pepys drafted some, which the duke presented to the Privy Council as his own. British naval administration was more centralized and efficient than the Dutch. With the help of Sir William Penn, Pepys composed The Duke of York's Sailing and Fighting Instructions, which, it has been asserted, are ‘still the basis for naval discipline’.42 Pepys allowed pursers to claim the full value of supplies according to the ship's authorized complement, lessening their opportunities for fraud. By letting them buy local, and thus better (and cheaper) food, instead of issuing more expensive stored vittles, such as salted meats, Pepys not only saved money but many men's lives.43

His most important reform came in 1677 with the introduction of examinations for promotion to lieutenant. Naval officers had already started to think of themselves as a separate profession: since the commonwealth they had been required to keep professional journals; the first club exclusively for naval officers was founded in 1674; tables of seniority appeared in 1692.44 Exams took this sense of being a special, exclusive fellowship further. Candidates for the exam had to be at least twenty years old, with a minimum of three years sea service, including one as a midshipman. The effects were instantaneous. For one thing exams decreased the influence of the ‘gentlemen’, a group Pepys disliked; for another they lessened the number of lieutenants begging for a ship. 'I thank God,’ Pepys wrote two months after their introduction, ‘we have not half the throng of those bastard breed pressing for employment.’45

Exams did not, of course, end patronage. Friends at court were an immense help in securing employment once the minimum sea time (which was doubled in 1703) had been served and the exam passed. Patronage helped get lieutenants seagoing appointments, and promotion to command ships as captains, and fleets as admirals. Because the main foreign enemy shifted from Spain to the Netherlands, the navy became concentrated at Chatham and Portsmouth, much nearer to London than Plymouth. This meant that officers were in closer contact with the capital, although they were too far away to stage a coup d'état. Fortunately, Charles II and James II promoted competent sea officers. Admittedly, gentlemen still held a distinct advantage, because they had the social skills and familial links to impress patrons and the powerful. Gentlemen were commissioned fifteen years sooner than tarpaulins, having served less time as volunteers and midshipmen than the latter, who had worked their way up as petty and warrant officers.46 Rather like the purchase system on land, the advantages that the gentlemen enjoyed ensured that the naval officer corps remained loyal to the establishment. Nonetheless the navy remained the career most open to talents. It required neither the purchase of a commission nor (unlike the church or law) a long and expensive education at the universities or Inns of Court.

The Second and Third Dutch Wars

Recently, historians have questioned whether trade was the real cause of the Dutch Wars, suggesting that their roots might lie in domestic factions and passionately held ideological differences. Pepys had no such doubts. ‘The trade of the world is too little for us two,’ he wrote in his diary for 2 February 1664, ‘therefore one must down.’47

The Second Dutch War broke out the following year as a result of trade disputes in the East Indies. Balladeers bragged:48

Dutchmen beware, we have a fleet,

Will make you tremble when you see't.

On 3 June 1665 the English and Dutch fleets met off Lowestoft. James, duke of York, came off best, but failed to follow through his victory. A year later the Dutch secured an advantage at the Battle of the North Foreland. The following month Prince Rupert and the earl of Albemarle won the Battle of St James's Day, which they followed up with an attack on Texel, destroying 150 enemy ships. A songster urged:49

Rejoice, brave English boys,

For now is the time to speak our joys;

The routed Dutch are run away;

And we have clearly won the day;

We are

now masters of the seas

And may with safety take our ease.

Foolishly, the government took the advice of such bombastic balladeers. Overconfident, it started to demobilize, neglecting defences, such as those at Chatham, which the Dutch sacked on 8–15 June 1667, destroying several ships of the line, and towing the flagship, the Royal Charles, back home in triumph (see ill.15). The subsequent blockade of the Thames terrified Londoners. ‘I think the Devil shits Dutchmen,’ Sir William Batten, the Surveyor of the Navy, babbled to Pepys.50 John Evelyn was so scared that he removed ‘my best goods, plate, etc., from my house to another place in the country’.51 After both sides had fought themselves to exhaustion, they signed a peace treaty at Breda in 1667.

The origins of the Third Dutch War may be found in another treaty, a secret one, signed at Dover on 1 June 1670, in which Charles accepted a £200,000-a-year subsidy from Louis XIV of France in return for fighting the Dutch. Hostilities began in 1672. On 28 May Admiral Michiel de Ruyter defeated the duke of York at the Battle of Solebay, thwarting an English landing in Holland. Even though James fought with great courage, having two flagships sunk under him, the public was horrified by the defeat. ‘We hear nothing but dismal news of death about the Fleet,’ wrote a lady friend to Philip Stanhope, earl of Chesterfield.52 During the Third Dutch War Britain lost 731 merchant ships to the Dutch (90 per cent of them to privateers). But the navy's fortunes improved enough by 1673 for Charles to sign a peace treaty the following year. No one deserved more credit for the navy's success in fighting the Dutch than James, duke of York, a brave admiral and a competent administrator.

The Revolution of 1688, England

It was a pity that James did not demonstrate similar abilities after he became king in 1685. Of course, his basic predicament was apparent long before then—he was a Catholic ruling an England in which at least 95 per cent of the population were Protestants. Unlike his brother, who kept his faith ambiguous, James did not hide his Catholicism, especially after being unfairly blamed for the sack of Chatham. Parliament attempted to exclude James from the throne, but Charles thwarted their efforts by dissolving it. To further facilitate his brother's accession he even sent the duke of Monmouth (the first of his sixteen acknowledged illegitimate children) into exile.

On 6 February 1685 Charles died and James came to the throne. Four months later Monmouth returned to England, landing in Lyme Regis with eighty-two men. Monmouth, a brave and experienced soldier, marched to Taunton, where the local ladies’ seminary presented him with a Bible, and the mayor proclaimed him the legitimate king on the spurious grounds that Charles had actually married Monmouth's mother, Lucy Walter. After failing to capture Bristol, the key to the west of England, Monmouth's army, now 3,700 strong, retreated to Sedgemoor in Somerset.

Today Sedgemoor is a quiet pastoral place, much drained, with cornfields, green pastures and wedges of swans. An anodyne plaque honouring those ‘WHO DOING THE RIGHT AS THEY GAVE [UNDERSTOOD] IT FELL IN THE BATTLE OF SEDGEMOOR, 6 JULY 1685’ masks the horrors that took place. In the small hours Monmouth attempted a night attack, which lost its surprise when someone accidentally discharged a weapon. Coming within range of the royalist forces, most of whom were behind a drainage ditch, the rebels fired but with little effect. In the ensuing rout Monmouth's army lost 1,400 killed and 500 taken prisoner compared to 80 killed and 220 wounded of the 2,500–3,000 royal forces. Many of the rebels did not die in combat but were murdered in hot or cold blood afterwards. ‘Our men are still killing them in the corn and the hedges and ditches, whither they are crept,’ wrote Captain Phineas Pett three hours after the battle. Adam Wheeler, a drummer in Colonel John Windham's company, saw one rebel, who ‘was shot through the shoulder, and wounded in the belly, he lay on his back in the sun stripped naked for the space on ten or eleven hours, in that scorching hot day to the admiration of all the spectators. And as he lay a great crowd of soldiers came about him and reproached him calling him “The Monmouth dog”.’ The treatment of the rebels immediately after Sedgemoor was shameful (see ill.16). Six prisoners were stripped naked and strung up from the sign of the White Hart Inn, Glastonbury. During his ‘bloody assizes’ the notorious Judge George Jeffreys sentenced four hundred people to death (including the burning alive of a pregnant woman accused of sheltering a rebel), and twelve hundred more to transportation.53 Acting in concert with Monmouth, Archibald Campbell, marquess of Argyle, sailed from Amsterdam to land on the Mull of Kintyre, Scotland, on 20 May. He brought three hundred followers, hoping that the Highlanders would flock to his standard. Few did, and Argyle was captured within the month, to be executed soon afterwards.

The rapid collapse of the Monmouth and Argyle Rebellions, plus the apparent approval of the harsh punishment of the rebels, suggested widespread support for the new regime. Yet within three years and three months James II had squandered all the goodwill that he had enjoyed at his accession by his quest to promote, if not restore, the Catholic faith. The king started by purging and packing powerful institutions. He called a parliament whose election he had much influenced: yet, unable to work with it, James dismissed it. He turned on his natural allies, the Tory party (descendants of the cavaliers), removing members of the established church and Oxford University from high offices. Yet nothing did the king greater harm than his policy towards the armed forces. The French ambassador, Paul Carillon, an astute observer of English affairs, thought that fear of James's armies was the greatest single grievance in the nation.54

James expanded his armies’ size and increased the number of Catholic officers. By 1686, 40 per cent of officers in the Irish Army were papists, prompting John Brenan, the Catholic bishop of Cashel, to gloat that the king ‘has made the army all Catholics’.55 Similar policies were pursued in the Scottish Army, where highly Protestant units were sent on foreign service to get them out of the way. All this confirmed the widely held impression that the English army and navy were riddled with papists (particularly among the officers), and the number of Catholics was growing. The actual picture is more complicated. While the percentage of Catholic army officers increased from 10 per cent to only 11 per cent, the proportion of them rose with seniority, with 27 per cent of the field officers and most of the regimental commanders being Catholics. Of other ranks, 15 per cent were papists, many of them being Irish troops brought over to England.56 The total number of Catholic officers increased with the enlargement of the army, which, thanks to rapidly expanding customs revenues from sugar and tobacco, grew during James's reign from 8,565 men to over 34,000. In relative terms the army was as large as Louis XIV's. Many feared James yearned to become as absolute a monarch as the French king. Two decades earlier Pepys had noted that ‘The design is, and the duke of York is hot for it, to have a land army, and so make the government like that of France.’ James confirmed such fears by ordering that some cannon cast in Scotland bear the motto ‘Haec est Vox Regis’ ('Here is the Voice of the King').57

James's policies towards the army played on three of the public's profoundest suspicions: the distrust of a standing army, which went back to Cromwell; the loathing of Catholicism, which started with the reformation; and a dread of absolutism, which Louis XIV's growing power fostered. Relations between soldiers and civilians deteriorated quickly before the Revolution of 1688. One member of parliament alleged that the king's troops were allowed ‘to outrage and injure whom they pleased’. Daniel Defoe complained about ‘the unspeakable oppression of the soldiery’.58 When the London magistrates tried to curb such excesses, the soldiery called them ‘cuckolds and should be made so by them’, adding that their worships ‘were not worthy to kiss their Arses’.59 By October 1687 relations became so bad that publicans started taking down their signs to avoid the unwelcome patronage of the three and a half thousand Catholic troops the king had just brought over from Ireland.60

Matters came to a head in 1688 over the king's attempt to suspend laws that discriminated against those who were not members of the Church of England. James appointed Sir Edward Hales, a Catholic, commander of an infantry regiment, while waiving the requirement that he take the Test Oath abjuring the Bishop of Rome that the law required from all accepting office under the crown. Hales's coachman, Arthur Godden, brought suit, hoping to collect the £500 fine that the law levied on offenders. In Godden v. Hales the judges found for the master not the minion. Lord Chief Justice Sir Edward Herbert explained that the king could dispense penal laws for ‘necessary reason’, of which he ‘is the sole judge’.61 The king exercised this power when he issued a Declaration of Indulgence that suspended laws penalizing non-Anglicans, and by ordering it read aloud from the pulpit on two successive Sundays, forced every Anglican priest, deacon and bishop in England into an act of humiliating obedience. Many refused. On the second appointed Sunday, 27 April, the hated Declaration was read in fewer than two hundred out of over nine thousand churches.62 In the face of such massive disobedience James ordered the seven bishops who petitioned against the Indulgence to be tried for seditious libel. After a London jury acquitted them on 30 June 1688, they were the heroes of the hour. As they were rowed up the Thames in triumph, crowds on either bank cheered them, their enthusiasm doubtless fuelled by the free wine and beer put out in the streets by substantial citizens.

Many soldiers shared their feelings. Indeed, before the trial, as the seven bishops were being led into the Tower, many of the guards asked for their blessings. After their acquittal James's main army, camped on Hounslow Heath, celebrated. The king, who was there dining with Lord Louis Feversham, an old comrade from the Battle of Southwold Bay, asked why the men were cheering. ‘It was nothing but the joy of the soldiers at the acquittal of the Bishops,’ their commander replied. ‘And you call that nothing?’ retorted a disheartened monarch.

For a man who less than a fortnight earlier had become father to a long-awaited male heir, James was in surprisingly low spirits. On 10 June, after eleven years of failure, the king's second wife, Mary of Modena, gave birth to a son. Yet the overwhelming majority of the people could not accept the baby's legitimacy, because a male heir meant the continuance of Catholic rule for the foreseeable future. Instead, they preferred to contend that the baby was a foundling, smuggled into the royal bedchamber in a warming pan. ‘Where one believes it, a thousand do not,’ wrote Anne, James's daughter, about her stepbrother's legitimacy.63 Seven members of the aristocracy—soon dubbed the ‘Immortal Seven'—sent William of Orange, the Stadholder of the Netherlands (who was married to Mary, James's eldest daughter), a letter inviting him to invade England and free its people from papist rule.

William landed at Torbay on 5 November 1688 with fifteen hundred men, only a quarter of whom were English mercenaries in Dutch service. Initially, few locals joined his army. Eight days after the landing a correspondent explained why: ‘most of our Western people having ever since Monmouth's time been troubled with dreams of gibbets’.64 To meet William's forces, the king's marched thirty thousand men west to Salisbury, leaving another nine thousand in reserve in garrisons. The odds were on James's side.

The same, however, could not be said of James's men. As they marched west tasked with repelling the invaders, their Catholic officers could not stop them from singing the wildly popular ‘Lillibullero’, an anti-papist satire in which a comic Irishman threatens:65

But if dispense do come from the Pope,

We'll hang Magna Carta and dem in a rope.

Bishop Gilbert Burnet, the contemporary historian, observed that ‘perhaps never has so slight a thing had so great an effect’. Its author, Thomas Wharton, boasted that it ‘sung a deluded prince out of three kingdoms’.66 James was expelled in a revolution that was in England, at least, a largely bloodless one, with about 150 deaths. It was also a surprising revolution—'one of the strangest catastrophes that is in history,’ thought Bishop Burnet, adding that ‘a Great King with strong armies and mighty fleets, a vast treasure and powerful allies, fell as at once.’67 Neither James nor his army wanted to fight.

On 16 November James left London to join the bulk of his forces at Salisbury, which he reached three days later. Lord Charles Middleton, the Secretary of State, reported him ‘in perfect health’. Suddenly, the king had a copious nosebleed, which lasted for at least forty-eight hours. Nothing could stem it. The ‘prodigious bleeding’ made him lethargic and incapable of taking decisions, a condition that his doctors worsened by medical bleeding, the cure-all of the day. James's disintegration was not combat fatigue: a reaction to too many days or weeks of intense fighting. He was a proven hero, his service under the French General Henri Turenne having earned him ‘a reputation for his undaunted courage’.68 In exile James rationalized his collapse as punishment for having broken his marriage vows so often and enthusiastically, warning his son that ‘Nothing has been more fatal to men, and to great men, than the letting themselves go to the forbidden love of Women.’69

Whatever its causes, the results of James's breakdown were immediate. Early in the morning of 23 November, hours after a council of war advised the king to retreat from Salisbury to London, John Churchill, his best and most influential general, deserted to William, taking half the royal army with him. The king fled to France. William warmly welcomed—yet never fully trusted—the turncoats. Parliament—or rather the Convention House of Commons, so called because true parliaments require a sitting monarch to call them into being—had William and Mary approve a Declaration of Right, before offering them the throne, which they accepted. The new monarchs conceded that ‘the raising or keeping of a standing army within the Kingdom in time of peace unless it be with the consent of parliament’ was ‘against Law’.70 To enforce this proviso parliament, fully mindful of recent mutinies, passed the Mutiny Act, which established a system of court martials. Since the act was set to expire within twelve months, it had to be re-enacted every year. Thus, in England, parliament made a standing army, and the army made a standing parliament.

The Revolution of 1688: Scotland and Ireland

In Scotland and Ireland events were very different. North of the border during the summer of 1689 John Graham, Viscount Dundee, raised three thousand Highlanders in King James's name. On 27 July they beat General MacKay's army at Killiecrankie. Dundee, however, was killed, leaving his men without a leader, to be defeated at Dunkeld on 21 August, and finished off at Cromdale the following May.

The war in Ireland, known as the War of the Two Kings, was far more serious and brutal. Although the Catholic Irish sympathized with James (Dublin's City Council having spent fifty pounds on claret to drink the warming pan baby's health), they viewed the war as one for Irish independence. Meanwhile, James, who landed in Ireland having sailed from France in March 1689, saw war in Ireland as little more than a stepping stone to regain his English and Scots thrones. Understandably, tensions between the two sides grew. John Stevens, a captain in the Jacobite army, called the Irish ‘a people used only to follow and converse with cows’.71

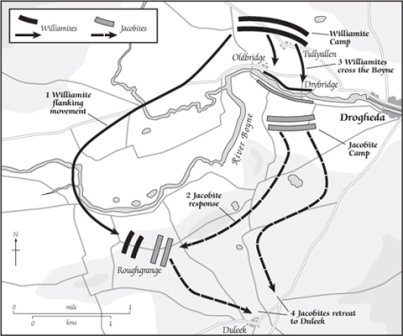

The war started in early 1689. In February Richard Talbot, earl of Tyrconnell, raised nearly forty-nine thousand troops, mostly Catholics. They invested the town of Derry, which after a siege of 105 days, the garrison having been forced to eat dogs, rats and horse flesh, was relieved on 28 July. The gallant defence of Derry helped produce the climactic Battle of the Boyne by persuading William to go to Ireland in person and confront James. Their two armies met at Oldbridge on the River Boyne, roughly a quarter of the way between Dublin and Belfast (see ill.17). Only half of William's men were British, who were neither as well equipped nor trained as his Dutch and Danish troops. Outnumbered by twenty-five to thirty-five thousand men, James was outfought by an even greater ratio. When William sent some of his forces to Rossnaree Ford, four miles to the west of Oldbridge, to cross the river and cut off James's retreat, he countered by dispatching two-thirds of his troops to stop them. It was a fatal mistake, for William had retained the bulk of his strength at Oldbridge, allowing him to cross the river and rout James's weakened army. They ran, a veteran recalled ‘like sheep flying before the wolf’. At ten that night James arrived in Dublin breathless, and after a hasty meeting of the Irish Privy Council decided to return to France. Once again he had lost his nerve. No wonder the Irish called him ‘Séamu an chaca'—'James the beshitten’.72

After being crushed at the Battle of Aughrim, 12 July 1691, the Irish made peace with William at Limerick the following October. The treaty was in fact an abject surrender, which allowed sixteen thousand troops, the so-called ‘wild geese’, to leave their native land for service in the French Army. The following year William destroyed James's last—and faintest—chance of regaining the throne when Admiral Edward Russell's fleet destroyed the French ships tasked for an invasion of England at Cap de la Hogue, near Cherbourg. From the cliffs James watched his hopes (plus several thousand French sailors) drown, exclaiming with a strange patriotic pride, ‘Ah! None but my brave English could do so brave an action’.73

7. Battle of the Boyne 1 July 1690.

Between the restoration and the Glorious Revolution, Britain's armed forces came of age. Even though many had wanted to abolish it, the standing army became institutionalized as the purchase system made it more acceptable, at least to the establishment. A large professional navy came into being, officered by competent men. As we have seen, after the accession of James II fears of a standing army grew as the king enlarged its size and the number of its Catholic officers. Ironically, the main contribution this powerful army made to the Revolution of 1688 was to do nothing. By refusing to fight for the old king, and by going over to the new one, it facilitated a largely bloodless revolution, at least in England. The Revolution of 1688 gave William what he wanted: the use of British forces against France to protect his beloved Holland. Had he lived longer he might have regretted his military achievements, for over the next half century they led to the decline of the Netherlands, while bringing together the forces that made Britain the pre-eminent world power.