Harry Potter simply wouldn’t be Harry Potter without spells and charms. There would be no Wingardium Leviosa, no Riddikulus and no charmed objects like the Marauder’s Map – not even a flying broomstick.

To become invisible, to make someone fall in love with you, to transform into another creature – these are all things that people have believed in, yearned for or feared throughout history. There’s nothing more magical than a magic charm.

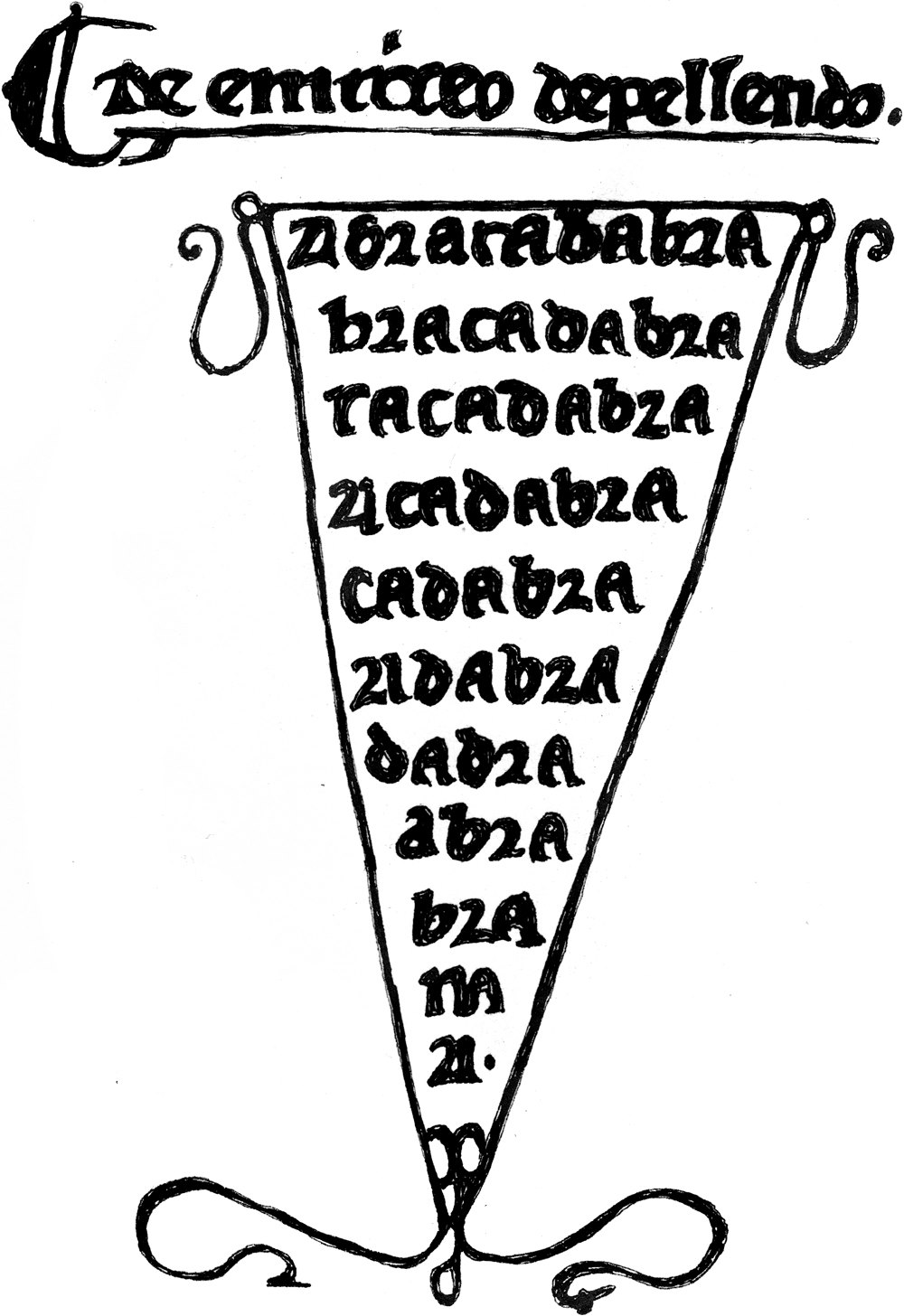

And perhaps one of the most powerful magic words of all is ‘Abracadabra!’

‘Avada Kedavra!’ Moody roared.

There was a flash of blinding green light and a rushing sound, as though a vast, invisible something was soaring through the air — instantaneously the spider rolled over onto its back, unmarked, but unmistakably dead.

Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire

Known today for its use by stage magicians when they perform illusions, ‘Abracadabra’ is probably familiar to us all. But it has more sinister connotations as well. Londoners used to paint it on their doors to ward off the plague in the 17th century. The infamous 20th-century English occultist Aleister Crowley believed it to be a word that held great power. Its power is certainly felt in the Harry Potter stories.

Its origins stretch back to Roman times. The word is first documented in the Liber Medicinalis (‘The Book of Medicine’), written by Quintus Serenus Sammonicus, who lived in the 2nd century AD and was physician to the Roman Emperor Caracalla. Sammonicus was actually executed by Caracalla in 212 AD, as part of a broader purge, but before then he’d suggested using the term he had coined as a cure or prevention against catching malaria, which he called hemitritaeos. Sufferers were instructed to write down the ‘Abracadabra’ charm repeatedly, leaving out one letter each time. This would create a ‘cone-shaped’ text, which looked like an inverted triangle standing on its point. The charm was then worn as an amulet designed to drive out fever. Who would have thought that battling mosquitoes would set the stage for the most dangerous spell in the wizarding world?

While ‘Abracadabra’ is a famous word that we know from a historically significant text, some charms have almost been lost to history. One of these was found on a tiny fragment of paper tucked inside an 18th-century magical text from Ethiopia, but it has the potential to be particularly powerful: it tells you how to turn yourself into a lion.

It was quite common in Ethiopia for magical practitioners to make collections of charms, spells and names of plants and their properties, which were copied down. The invocation to turn yourself into a lion was found hidden in one of the resulting handbooks. It was written in an ancient Ethiopian language – Ge’ez – and it’s hard to tell just how old the fragment is. It might date from the same time, or from even earlier than the manuscript in which it was found.

Although Ethiopia was declared a Christian country in the 3rd century AD, it didn’t lose its Babylonian, Egyptian and Islamic influences. The indigenous African magic tradition was vying with new influences from outside the culture. This particular talisman to change yourself into a lion or serpent is an early example of the type of Transfiguration that we know so well from Professor McGonagall’s classes.

Changing yourself into a lion was not a straightforward process: it required outside assistance. This came in the form of specialised Ethiopian magic practitioners called Däbtäras. Why you might seek them out varied, but if you wanted to transform yourself into a lion or a similar beast, it might be because you were at war – or in need of an aggressive, attacking presence.

Whether the magic worked or not was said to depend on outside circumstances. Sometimes the magic was interfered with by a witch or a counter-prayer against the spell itself. We might think today that the idea of a charm working like this is a little hard to believe, but Däbtäras have practised in Ethiopia for centuries and continue to do so.

‘Transfiguration is some of the most complex and dangerous magic you will learn at Hogwarts,’ she said. ‘Anyone messing around in my class will leave and not come back. You have been warned.’

Then she changed her desk into a pig and back again.

Professor McGonagall – Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone

Charms have the power to allow entry into Diagon Alley, and are also key to keeping its secrets. The bustling centre of wizarding retail therapy is where Harry acquires his holly and phoenix-feather wand (and other necessities) before setting off for his first term at Hogwarts.

When J.K. Rowling was planning how a wizard or witch would access Diagon Alley, she created a six-stage drawing, like a cartoon strip. The first stage shows an ordinary brick wall with an old metal dustbin in front of it. In the second, an umbrella touches a brick in the middle of the wall. In the third, the bricks start to spin. In the fourth and fifth, a round opening forms and you can begin to see the old-fashioned street. Finally, there is a fully formed archway, and Diagon Alley is revealed.

Drawing of the opening to Diagon Alley by J.K. Rowling (1990)

The brick he had touched quivered – it wriggled – in the middle, a small hole appeared – it grew wider and wider – a second later they were facing an archway large enough even for Hagrid, an archway on to a cobbled street which twisted and turned out of sight.

Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone

Underlying this delightful magical process is carefully crafted logic. It’s not simply a case of flicking a wand and, Lo! Here appears Diagon Alley. There is a specific brick that needs to be tapped, a little like a combination lock.

J.K. Rowling rooted Harry Potter in historical and folkloric traditions and brought it all into the modern world. She created a magic world that co-exists with our own, and specified the careful boundaries and techniques of how its magic worked. Her process was to figure this out visually as much as in the drafts of her writing, making the magic more vivid and real, and allowing us vanishing glimpses into what wizarding life might look like. It was clear early on that this was not your typical magical story.

We’ve seen how charms could be used for transfiguring into other creatures and transporting yourself into new magical places, but there were also charms that could be used for more malign purposes, such as getting the upper hand over your enemies.

There was a charm from the Egyptian city of Thebes, dating from the 4th century AD, which let you do just that. In the papyrus document later found that described it, there were seven pages of incantations, which included charms to discover thieves and to reveal the secret thoughts of men. The spells and charms were written in Ancient Greek and one page showed you how to transform a ring into a charm.

Spells like these weren’t supplications or prayers, but commands to demonic entities. To get a demon to obey you, you needed two things: the demon’s full and exact name, and a physical way to make sure it did as it was told. So, in this case, the magical papyrus recipe book gave you the demon’s name and the correct incantation, while the iron ring was the target of the magic that established a physical bond. It was intended that the ring be hidden in the ground in order to prevent something from happening. By inscribing and burying the ring, the owner could specify, for example, that they did not want a rival to be lucky in love.

Summoning demons was a high-risk activity. Egyptian mythology in the 4th century AD saw a huge number of gods vying with each other. Greek and Roman gods were worshipped, Christianity was starting to spread across the Roman Empire and the Ancient Egyptian gods were still in the picture. The result was that people believed in many things simultaneously and practised magic alongside their religious observance. Summoning demons into the resulting mêlée was considered perfectly normal.

‘Amortentia doesn’t really create love, of course. It is impossible to manufacture or imitate love. No, this will simply cause a powerful infatuation or obsession. It is probably the most dangerous and powerful potion in this room — oh yes,’ he said, nodding gravely at Malfoy and Nott, both of whom were smirking sceptically. ‘When you have seen as much of life as I have, you will not underestimate the power of obsessive love...’

Professor Slughorn – Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince

It’s much more fun to summon Cupid than to summon a demon. Love charms are the oldest charms of all. There are love rituals scratched on cuneiform tablets from four thousand years ago and there seem to be love charms in every place on the planet and in every moment in history.

Love charms have stretched well into the 20th century. One example found in the Netherlands is a charm between two people painted onto a beautiful oyster shell; oysters strongly symbolise love. One of the initials is ‘J’ and the other is ‘R’, with two hearts in between, connected at the tip. One of the initials is accompanied by the astrological symbol for Gemini, and the other one the symbol for Taurus. A red thread connects the two letters as well – a symbol of the couple’s love. Let’s hope the ‘R’ doesn’t stand for Ron Weasley, given his history with magical love concoctions...

‘Professor, I’m really sorry to disturb you,’ said Harry as quietly as possible, while Ron stood on tiptoe, attempting to see past Slughorn into his room, ‘but my friend Ron’s swallowed a love potion by mistake. You couldn’t make him an antidote, could you?’

Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince