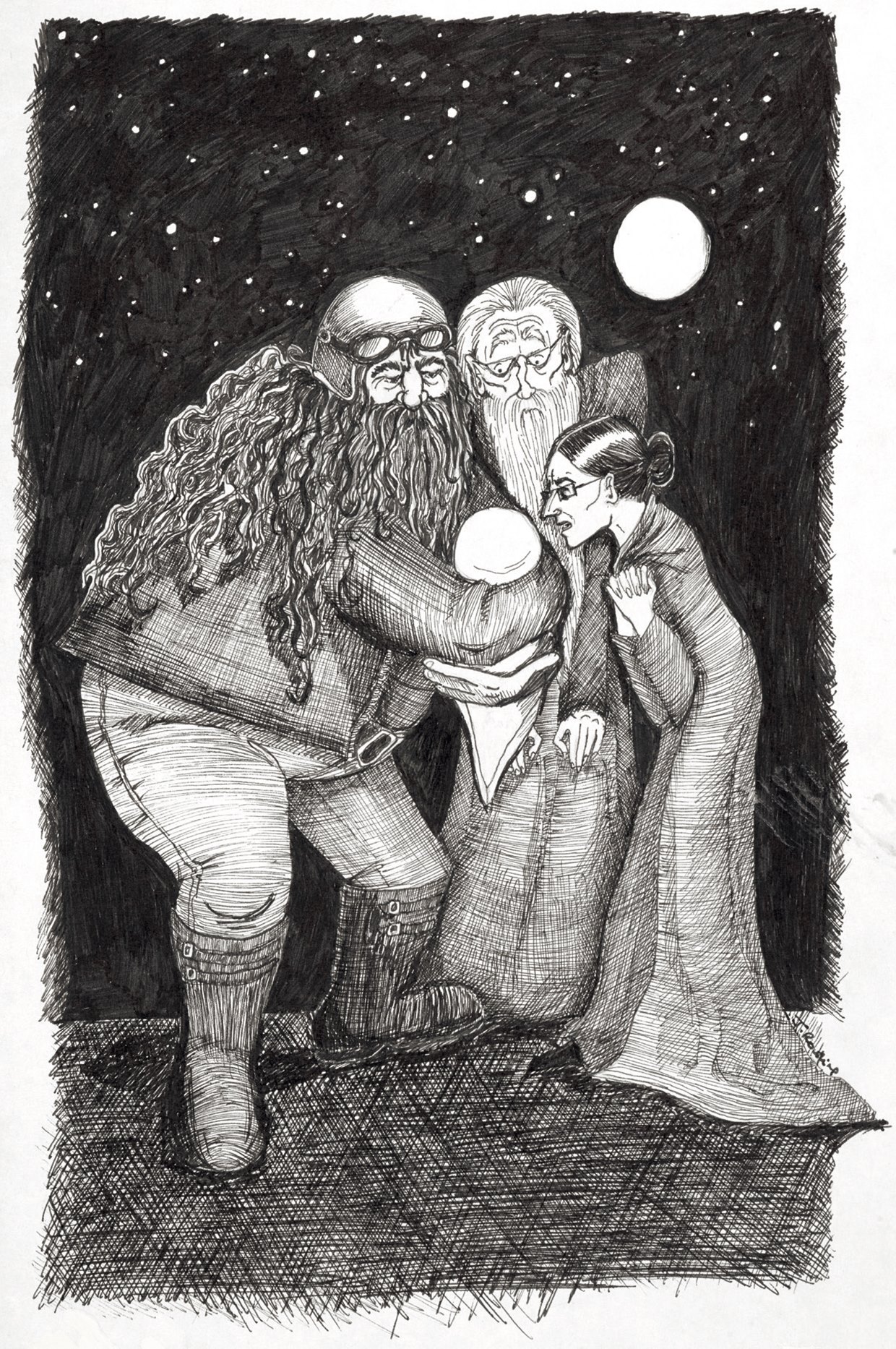

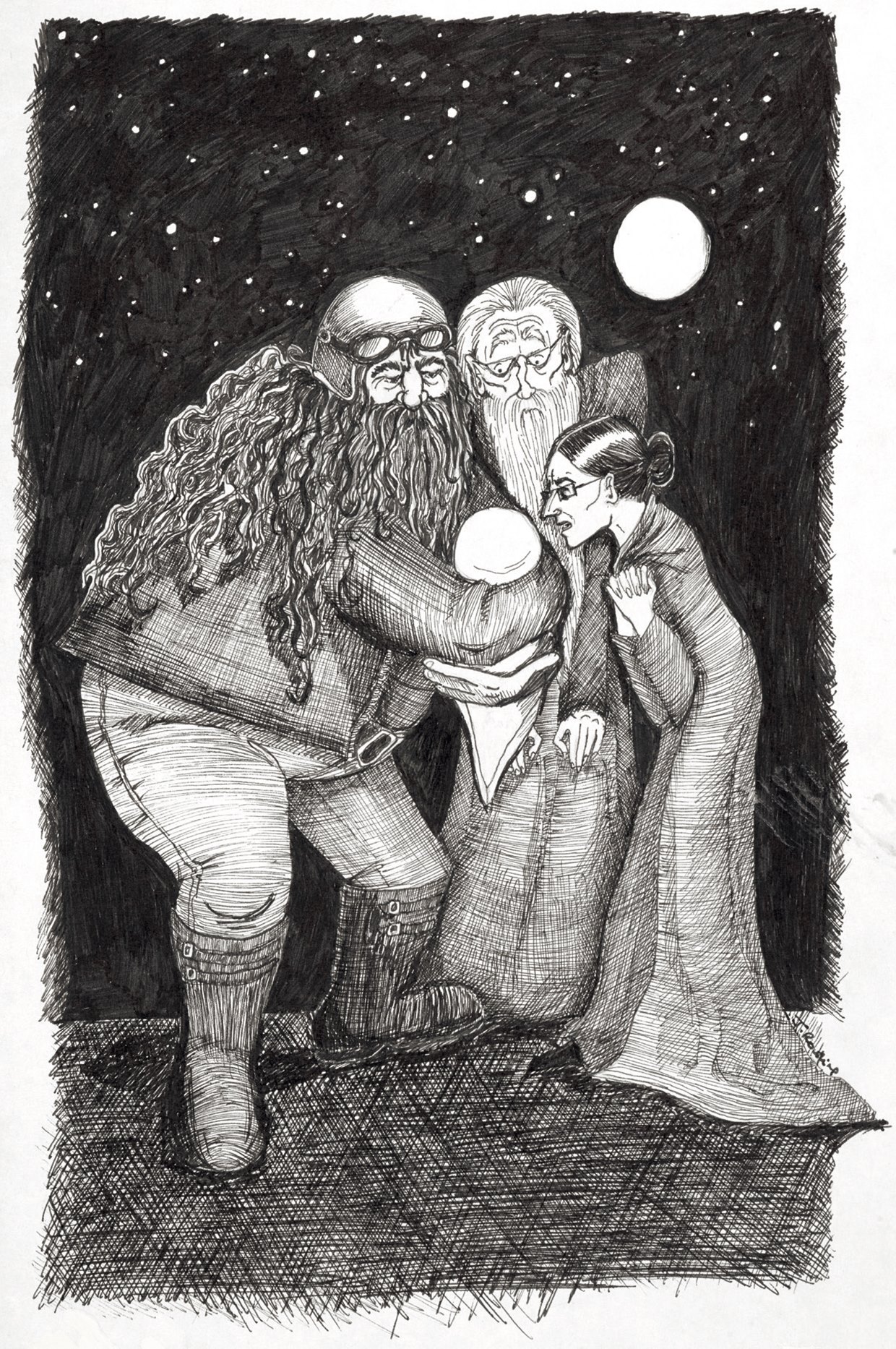

Drawing of Harry Potter, Dumbledore, McGonagall and Hagrid by J.K. Rowling

For Harry, Defence Against the Dark Arts was the most important subject at Hogwarts. It kept him alive and helped him greatly in his crusade against the Death Eaters and Dark Magic. Years before his arrival at Hogwarts, when he was just a baby, he faced its greatest practitioner, Lord Voldemort – and lived!

‘It’s – it’s true?’ faltered Professor McGonagall. ‘After all he’s done… all the people he’s killed… he couldn’t kill a little boy? It’s just astounding… of all the things to stop him… but how in the name of heaven did Harry survive?’

‘We can only guess,’ said Dumbledore. ‘We may never know.’

Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone

Harry lived, but his parents died in the confrontation. As she drafted Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, J.K. Rowling drew her own vision of the moment when we first meet Harry Potter, as a baby, fresh from his encounter with the Dark Lord, being delivered to Number Four, Privet Drive.

Drawing of Harry Potter, Dumbledore, McGonagall and Hagrid by J.K. Rowling

The sketch depicts a dark night with only the moon and stars to light the scene, after Dumbledore has extinguished all the streetlights with his Deluminator. Hagrid stoops to show the baby to Dumbledore and McGonagall. All we can see of Harry is the crown of his head wrapped in a white blanket, shining as brightly as the moon up above. The drawing is full of atmosphere and emotion, as it captures this pivotal moment in the stories: the very beginning of Harry’s story.

It’s tied to an exact moment – a paragraph where the three of them are standing looking at Harry, and McGonagall has just expressed concern about him being left with the Dursleys: ‘These people will never understand him! He’ll be famous – a legend – I wouldn’t be surprised if today was known as Harry Potter Day in the future – there will be books written about Harry – every child in our world will know his name!’

Of course, Dumbledore knew how Harry survived. He knew that the greatest defence against Dark Magic was love.

One small hand closed on the letter beside him and he slept on, not knowing he was special, not knowing he was famous, not knowing he would be woken in a few hours’ time by Mrs Dursley’s scream as she opened the front door to put out the milk bottles, nor that he would spend the next few weeks being prodded and pinched by his cousin Dudley… He couldn’t know that at this very moment, people meeting in secret all over the country were holding up their glasses and saying in hushed voices: ‘To Harry Potter – the boy who lived!’

Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone

From Red Caps they moved on to Kappas, creepy water-dwellers that looked like scaly monkeys, with webbed hands itching to strangle unwitting waders in their ponds.

Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban

If you happen to come upon a peaceful river in Japan: beware! A demon, or kappa, may be ready to drag you into the watery depths. The kappa takes its name from the Japanese for ‘river’ (which is kawa) and ‘child’ (which is wappa) – both conjoined to make ‘kappa’.

J.K. Rowling based her description of kappas on existing Japanese folklore; they look a bit like monkeys, but with fish scales instead of fur, and with webbed hands and feet (for ease of travel through water). Some say they have fangs, others that they have a beak. There are differences in opinion about their character, too. Some stories see kappas as innocent but mischievous creatures. Others tell of demons that kidnap children, eat human flesh and drown unsuspecting victims. But what everyone agrees on is that kappas have a saucer-shaped space in the top of their heads filled with water – and they love cucumbers.

In 1855, Akamatsu Sotan, doctor and local historian, published Tonegawa Zushi, which is a history of the Tone River in the Kanto region of Japan. The book explored the folklore and traditions of the people who lived along the river and included an illustration of a kappa: it is shown in black and white, with a bowl in the middle of its head and wild hair that looks like a chimney sweeper’s brush. And, according to Sotan, kappas would move along the Tone River every year, causing chaos and havoc wherever they went.

Kappas were also depicted as netsuke – a small decorative clasp used on Japanese robes. Both decorative and protective, it was probably a bit of fun as well: having a kappa on your side could prove useful.

There are ways to defend yourself against kappas. You need to remember that they’re dangerous but also incredibly polite, and that the bowl in their head is full of water, which they need in order to survive. If you ever encounter one and it looks like it wants to kidnap you and drag you away to its watery lair… bow to it! It will bow back in obedience, the water will spill out and it will die.

Should you ever want to bathe in a Japanese river, people believe to this day that kappas can be placated by writing your name, or that of your family, onto cucumbers and tossing them into the water. The cucumber is the kappa’s favourite meal and should provide a necessary distraction for you to enjoy your swim in peace!

Then, as he strode down a long, straight path, he saw movement once again, and his beam of wand-light hit an extraordinary creature, one which he had only seen in picture form, in his Monster Book of Monsters.

It was a sphinx.

Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire

The world’s most famous sphinx lives in Egypt, carved out of solid rock around 4,500 years ago. It has the head of a man and the body of a lion. But sphinxes aren’t just Egyptian: in Greek mythology, a sphinx has the body of a lion and the head of a woman – plus the wings of a bird. The sphinx is legendarily treacherous and murderous. Some think the word ‘sphinx’ has its roots in the Greek for ‘to strangle’ – which is what Greek sphinxes did to their victims.

Egyptian sphinxes were apparently much friendlier – though they still possessed ferocious strength. In both traditions, however, they’re found as guardians in front of temples, where they ask riddles of those who approach. In The Historie of Foure-Footed Beasts, published in 1607 by an English vicar called Edward Topsell, a sphinx appears alongside more common (and real) animals like rabbits, cats and even a version of German artist Albrecht Dürer’s rhinoceros.

Topsell admitted that he cribbed a lot of the information from an earlier German work, Historia animalium. But The Historie of Foure-Footed Beasts is important, as it’s the first book published in the English language explaining the animal kingdom.

In it, we’re told that toads have a ‘toadstone’ in their heads that will protect people from poison; lemmings graze in the clouds; elephants worship the sun and the moon, and become pregnant by chewing on mandrake; apes are terrified of snails and weasels give birth through their ears.

Topsell describes the sphinx as having the face of a woman, with the bottom half of the body being apelike and covered in hair, not much like a lion at all. It has a ‘fierce but tameable nature’ and can store food in its cheeks until it’s ready to eat, like a guinea pig. Its voice is that of a man: ‘sounding as if one did speak hastily with indignation or sorrow’.

Topsell describes the Riddle of the Sphinx as it appeared in Greek mythology from the story of Oedipus. That riddle asked: what is the creature that walks first on four legs, then on two legs and lastly on three? The answer is man – you start off crawling as a baby, then you walk, then you walk with a stick. It’s hard to tell whether Topsell believed these creatures really existed or not. He certainly liked to write about them as if they did.

Then she spoke, in a deep, hoarse voice. ‘You are very near your goal. The quickest way is past me.’

‘So… so will you move, please?’ said Harry, knowing what the answer was going to be.

‘No,’ she said, continuing to pace. ‘Not unless you can answer my riddle. Answer on your first guess – I let you pass. Answer wrongly – I attack. Remain silent – I will let you walk away from me, unscathed.’

Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire

Every year around a million people head to Times Square in New York City for New Year’s Eve celebrations. At midnight, a huge illuminated ball drops from a specially designed flagpole on top of 1 Times Square, a building famous for its dazzling advertising displays.

But if you go behind the advertising hoardings, the complex electrics for the LED lighting and the tangle of internet wires, you’ll find an almost deserted building.

This was once the headquarters of the New York Times and it’s the building that gives Times Square its name. The New York Times located their office there in 1905 and the owner, Adolph Ochs, had his office right at the top: an observatory – guarded by eight gargoyles. In 1908, it was Ochs who came up with the idea of the illuminated ball descending a pole as the crowd counted down to midnight.

Since he had last seen it, the gargoyle guarding the entrance to the Headmaster’s study had been knocked aside; it stood lopsided, looking a little punch-drunk, and Harry wondered whether it would be able to distinguish passwords anymore.

‘Can we go up?’ he asked the gargoyle.

‘Feel free,’ groaned the statue.

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows

Gargoyles came about from a simple need to drain water off the roofs of the massive, monumental religious structures that sprung up in northern Europe before the Protestant Reformation of the 16th century. If you have to do it, do it in style! Rainwater would run off angled or gabled roofs, drain down into gutters and then into a gargoyle – a water spout, which would deflect the water away from the building, preventing damage to it.

The New York gargoyle is not really a gargoyle at all. The word comes from the French gargouille, meaning ‘throat’, but if it’s purely decorative, it’s actually a chimaera. Both look scary and are implacable defenders against the dark arts. The reason gargoyles look so frightening – all horns, teeth and beaks – is to frighten evil spirits from religious buildings and literally regurgitate that which would damage them, in the form of water. Inside, you’re safe. In the New York skyline gargoyles are sentinels, keeping guard over cathedrals, bookstores, banks, offices and schools – all with the best vantage points in the city.

1 Times Square was only the tallest skyscraper in the world for a short time; its record didn’t last a year and the newspaper moved out within a decade. The building was sold, resold and renovated. In the Nineties, it was finally completely hidden by the advertising displays we know today. But it’s still there, unseen by the millions that pass by. As for one of the New York gargoyles – it now lives on the third floor of the New-York Historical Society museum, continuing its endless vigil.

He pushed his greying hair out of his eyes, thought for a moment, then said, ‘That’s where all of this starts – with my becoming a werewolf. None of this could have happened if I hadn’t been bitten… and if I hadn’t been so foolhardy…’

Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban

Harry’s favourite teacher of Defence Against the Dark Arts was Remus Lupin: warrior in the First Wizarding War, close friend to Harry’s departed parents, teacher of the Patronus Charm, provider of chocolate in a crisis… and werewolf.

In the wizarding world, it’s hard to be a werewolf. The monthly transformations take their toll on the body. They are largely shunned by the wizarding world, with few career options or chances of friendship. If left alone, the werewolf will injure itself in frustration, or if it gets desperate.

‘My transformations in those days were – were terrible. It is very painful to turn into a werewolf. I was separated from humans to bite, so I bit and scratched myself instead. The villagers heard the noise and the screaming and thought they were hearing particularly violent spirits. Dumbledore encouraged the rumour… even now, when the house has been silent for years, the villagers don’t dare approach it…’

Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban

Back in the 15th century, Johann Geiler von Kaysersberg was considered one of the greatest preachers of his age. His sermons were so popular that they even built him his own pulpit in Strasbourg cathedral. He was known as ‘the educator of Germany’. During a series of sermons for Lent in 1508, he (naturally!) decided to cover werewolves.

Collected in a publication called De Emeis (‘The Ants’), alongside a woodcut of a fierce wolf attacking an old, bearded man, von Kaysersberg’s sermon listed seven reasons why werewolves attack people: 1) hunger, 2) savageness, 3) old age (of the werewolf, not its victim), 4) experience, 5) madness, 6) the devil and 7) God, for reasons which aren’t immediately clear.

There was a terrible snarling noise. Lupin’s head was lengthening. So was his body. His shoulders were hunching. Hair was sprouting visibly on his face and hands, which were curling into clawed paws.

Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban

Tales of werewolves also sometimes formed a part of witchcraft trials. There were occasional accusations of lycanthropy – transforming into a wolf – along with wolf charming or wolf riding. Throughout the 16th to 18th centuries, there were sporadic trials across Europe in which men and women confessed that a demon had given them a ‘wolf skin’, which they hid under a rock when they weren’t using it.

It’s possible that Johann Geiler von Kaysersberg was aware of stories about lycanthropy, but several of his sermons were copied down and published without his approval, so there is a chance that this lupine-themed sermon was attributed to him when he never actually said it. Nonetheless, the powerful legend of shape-shifters had begun to take hold in central Europe five hundred years ago, and it still haunts popular culture today – let’s face it, it’s hard to look at a full moon without thinking about Lupin and that transformation.

You’ll need to be prepared to face a number of strange and sometimes frightening creatures such as werewolves in Defence Against the Dark Arts. The subject at Hogwarts is beset with calamity, its roll-call of teachers cursed with dark secrets or uncontrollable character traits (not to mention physical transformations!). In the beginning, the lessons teach a form of protection against Dark Magic and dark creatures, and for Harry, all of that is in aid of the best cause of all: defeating Lord Voldemort. No one said that would be easy, as the nature of the evil he embodies changes many times during the character’s development. Harry needs more than a snakelike wand to cast out that particular evil, but he succeeds – eventually.