The Preparation of Herbs

The Preparation of Herbs

Part of the art of herbal medicine is knowing what techniques to use in preparing the remedies. Various methods of using plants have developed over the centuries to enable their healing properties to be released and become active. After the right choice of herbs has been made, the best way to prepare them must be selected.

No doubt the first way in which our ancestors used herbs was by eating the fresh plant. Since then, over the thousands of years during which herbs have been used, other methods of preparing them have been developed. With our modern knowledge of pharmacology we can make conscious choices as to which process we use to release the biochemical constituents needed for healing without insulting the integrity of the plant by isolating fractions of the whole.

From what has been said so far in this book it should be clear that the property of any herb is not just the sum of all the actions of various chemicals present. There is a synergy at work that acts to create a therapeutic whole that is more than the sum of its parts. If the method of preparation destroys or loses part of the whole, much of the healing power is lost. The preparation must be done carefully and consciously.

Methods of preparation are mentioned throughout the book, but they are not described in detail each time. In this section we will give a thorough explanation of methods; however, some of the examples used may require reference to other chapters for full understanding.

For clarity we will divide the methods into those that are for use inside the body and those for external use.

Internal Remedies

From a holistic perspective, the best way of using herbs is to take them internally, since it is from within that healing takes place. The ways of preparing internal remedies are numerous, but with all of them it is essential to take care with the process to ensure you end up with what you want.

There are three basic kinds of preparations for taking internally:

1. Water-based

2. Alcohol-based

3. Fresh or dried herbs

Water-based preparations

There are two ways to prepare water-based extracts: infusions and decoctions. When the herb to be used contains any hard, woody material, decoctions are used; otherwise infusions are used.

Infusion

If you know how to make tea, you know how to make an infusion. It is perhaps the most simple and common method of taking a herb and fresh or dried herbs can be used to prepare it. However, where one part of dried herb is prescribed, it can be replaced by three parts of the fresh herb, the difference being due to the higher water content of the fresh herb. Therefore if the instructions call for one teaspoonful of dried herb, it can be substituted by three teaspoonfuls of fresh herb.

To make an infusion:

1. Take a china or glass teapot which has been warmed and put one teaspoonful of the dried herb or herb mixture into it for each cup of tea.

2. Pour a cup of boiling water in for each teaspoonful of herb that is already in the pot and then put the lid on. Leave to steep for ten to fifteen minutes.

Infusions may be drunk hot—which is normally best for a medicinal herb tea—or cold, or have ice in them. They may be sweetened with Liquorice Root, honey or even brown sugar.

Herbal teabags can be made by filling little muslin bags with herbal mixtures, taking care to remember how many teaspoonfuls have been put into each bag. They can be used in the same way as ordinary teabags.

To make larger quantities to last for a while, the proportion should be 30 grams (one ounce) of herb to half a litre (one pint) of water. The best way to store it is in a well-stoppered bottle in the refrigerator. However, the shelf life of such an infusion is not very long, as it is so full of life force that any micro-organism that enters the infusion will multiply and thrive in it. If there is any sign of fermentation or spoiling, the infusion should be discarded. Whenever possible, infusions should be prepared when needed.

Infusions are most appropriate for plant parts such as leaves, flowers or green stems, where the substances wanted are easily accessible. If we also want to infuse bark, root, seeds or resin, it is best to powder them first to break down some of their cell walls and make them more accessible to the water. Seeds for instance, like Fennel and Aniseed, should be slightly bruised before being used in an infusion to release the volatile oils from the cells. Any aromatic herb should be infused in a pot that has a well-sealing lid, to ensure that only a minimum of the volatile oil is lost through evaporation.

When we are working with herbs that are very sensitive to heat, either because they contain highly volatile oils or because their constituents break down at high temperature, we can also make a cold infusion. The proportion of herb to water is the same, but in this case the infusion should be left for six to twelve hours in a well sealed earthenware pot. When the liquid is ready, strain and use it.

As an alternative, cold milk can also be used as a base for a cold infusion. Milk contains fats and oils which aid in the dissolution of the oily constituents of plants. These milk infusions can also be used for compresses and poultices, adding the soothing action of milk to that of the herbs. There is however one contraindication for the use of milk in an infusion: if there is any evidence of an internal reaction to milk in the form of over-sensitivity or allergy, or if the skin becomes irritated when it is applied externally, then avoid such infusions.

The infusions made as directed will be the base for many other preparations described later.

Apart from the purely medicinal use of herbs with which this book is mostly concerned, herbs can make an exquisite addition to one’s lifestyle and can open a whole world of subtle delights and pleasures. They are not only medicines or alternatives to coffee, but can in their own right make excellent teas. Whilst each person will have their own favourite herbs, here is a list of some which make delicious teas, either singly or in combination. From this list you can select those which you like the taste of most, or those that also augment your health:

Barberry

Flowers: Chamomile, Elder Flower, Hibiscus, Lime Blossom, Red Clover

Leaves: Peppermint, Spearmint, Lemon Balm, Rosemary, Sage, Thyme, Hyssop, Vervain

Berries: Hawthorn, Rose Hips

Seeds: Aniseed, Caraway, Celery, Dill, Fennel

Roots: Liquorice

Decoction

Whenever the herb to be used is hard and woody, it is better to make a decoction rather than an infusion to ensure that the soluble contents of the herb actually reach the water. Roots, rhizomes, wood, bark, nuts and some seeds are hard and their cell walls are very strong, so to ensure that the active constituents are transferred to the water, more heat is needed than for infusions and the herb has to be boiled in the water.

To make a decoction:

1. Put one teaspoonful of dried herb or three teaspoonfuls of fresh material for each cup of water into a pot or saucepan. Dried herbs should be powdered or broken into small pieces, while fresh material should be cut into small pieces. If large quantities are made, use 30 grams (one ounce) of dried herb for each half litre (one pint) of water. (These are general guidelines, more specific dosages for each herb are given in the herbal section.) The container should be glass, ceramic or earthenware. If using metal it should be enamelled. Never use aluminium.

2. Add the appropriate amount of water to the herbs.

3. Bring to the boil and simmer for the time given for the mixture or specific herb, usually ten to fifteen minutes. If the herb contains volatile oils, put a lid on.

4. Strain the tea whilst still hot.

A decoction can be used in the same way as an infusion.

When preparing a mixture containing soft and woody herbs, it is best to prepare an infusion and a decoction separately to insure that the more sensitive herbs are treated accordingly.

When using a woody herb which contains a lot of volatile oils, it is best to make sure that it is powdered as finely as possible and then used in an infusion, to ensure that the oils do not boil away.

Alcohol-based preparations

In general, alcohol is a better solvent than water for the plant constituents. Mixtures of alcohol and water dissolve nearly all the relevant ingredients of a herb and at the same time act as a preservative. Alcohol preparations are called tinctures, an expression that is occasionally also used for preparations based on glycerine or vinegar, as described below.

The methods given here for the preparation of tinctures show a simple and general approach; when tinctures are prepared professionally according to descriptions in a pharmacopoeia, specific water/ alcohol proportions are used for each herb, but for general use such details are unnecessary.

For home use it is best to take an alcohol of at least 30% (60 proof), vodka for instance, as this is about the weakest alcohol/water mixture with a long term preservative action.

To make an alcoholic tincture:

1. Put 120 grams (four ounces) of finely chopped or ground dried herb into a container that can be tightly closed. If fresh herbs are used, twice the amount should be taken.

2. Pour half a litre (one pint) of 30% (60 proof) vodka on the herbs and close tightly.

3. Keep the container in a warm place for two weeks and shake it well twice every day.

4. After decanting the bulk of the liquid, pour the residue into a muslin cloth suspended in a bowl.

5. Wring out all the liquid. The residue makes excellent compost.

6. Pour the tincture into a dark bottle. It should be kept well stoppered.

As tinctures are much stronger, volume for volume, than infusions or decoctions, the dosage to be taken is much smaller, between 5 and 15 drops, depending on the herb taken (see the Herbal section for details).

We can use tinctures in a variety of ways. They can be taken straight or mixed with a little water, or they can be added to a cup of hot water. If this is done, the alcohol will partly evaporate and leave most of the extract in the water, which with some herbs will make the water cloudy, as resins and other constituents not soluble in water will precipitate. Some drops of the tincture can be added to a bath or footbath, or used in a compressor mixed with oil and fat to make an ointment. Suppositories and lozenges can be made this way too.

Another most pleasant way of making a kind of alcohol infusion is to infuse herbs in wine. Even though these wine based preparations do not have the shelf life of tinctures and are not as concentrated, they can be very pleasant to take and most effective in some conditions. There is a long history of using wine in this way, and in fact most aperitifs and liqueurs were originally herbal remedies, based on herbs such as Wormwood, Mugwort and Aniseed as aids to the digestive process.

In her book Herbal Medicine, Dian Dincin Buchman gives the following excellent recipe for a tonic wine with a very nice taste:

1 pint Madeira

1 sprig of Wormwood

1 sprig of Rosemary

1 small bruised Nutmeg

1 inch of bruised Ginger

1 inch of bruised Cinnamon Bark

12 large organic raisins

“Pour off about an ounce of the wine. Place herbs in the wine. Cork the bottle tight. Place the bottle in a dark, cool place for a week or two. Strain off the herbs. Combine this medicated wine with a fresh bottle of Madeira and mix thoroughly. Sip a small amount whenever needed. It helps settle the stomach, gives energy and makes you feel better.”

Just about any herbal wine can be made simply by steeping the herbs in a wine. Another commonly used kind is Rosemary wine:

1 bottle white wine

1 handful of fresh Rosemary leaves

Steep the leaves for about a week in the wine and then filter the herbs off. You can use it whenever needed and it will help to settle the digestion and act as a mild relaxing nervine.

You can also ferment the herbs themselves; after all, even grapes are herbs. All the aromatic herbs make exquisite wines, and Elderberry and Dandelion are especially useful as medicinal wines. To make a good Dandelion wine you will need:

2 litres (4 pints) of Dandelion Flowers

1 tablespoonful of bruised Ginger Root

the peel of 1 orange, finely cut

the peel of 1 lemon, finely cut

700 grams (1½ lb) of demerara sugar

the juice of 1 lemon

1 teaspoonful of wine yeast

Bring the 2 litres (4 pints) of water to the boil and then leave to cool. Separate the flowers of Dandelion from the bitter stalks and calyx and put them in a large bowl. Pour the cooled water over the flowers and leave for a day, stirring occasionally. Pour the whole into a large pot, add the Ginger and the rinds of orange and lemon, then boil for 30 minutes. Strain the liquid and pour it back into the rinsed bowl. Mix the sugar and the lemon juice into the bowl and allow the mixture to cool. Then cream the wine yeast with some of the liquid and add it to the bowl. Cover the bowl with a cloth and leave it to ferment in a warm place for two days, keeping a dish under the bowl to catch any liquid that may froth over the brim. After two days, pour the liquid into a cask which you have to bung with cotton wool to allow any gas to escape, or pour it into a jar that has an air lock (these bottles and airlocks are commonly available from chemists’ shops in the UK or from home brewing suppliers in other countries). Leave the mixture in the cask until all the fermentation has ceased, when gas bubbles no longer form. Then close the cask tightly for about two months. Finally siphon the clear liquid into bottles, which have to be kept for another six months before they are ready for drinking.

Vinegar-based tincture

Tinctures can also be made using vinegar, which contains acetic acid that acts as a solvent and preservative in a way similar to alcohol. Whenever you make a vinegar tincture, it is best to use apple cider vinegar, as it has in itself excellent health augmenting properties. Synthetic chemical vinegar should not be used. The method is the same as for alcoholic tinctures and if you steep spices or aromatic herbs in vinegar, the resulting fragrant vinegar will be excellent for culinary use.

Glycerine-based tincture

Tinctures based on glycerine have the advantage of being milder on the digestive tract than alcoholic tinctures, but they have the disadvantage of not dissolving resinous or oily materials quite as well. As a solvent glycerine is generally better than water but not as good as alcohol.

To make a glycerine tincture, make up half a litre (one pint) of a mixture consisting of one part glycerine and one part water, add 110 grams (4 ounces) of the dried, ground herb and leave it in a well-stoppered container for two weeks, shaking it daily. After two weeks, strain and press or wring the residue as with alcoholic tinctures. For fresh herbs, due to their greater water content, put 220g (8oz) into a mixture of 75% glycerine/25% water.

Syrup

In the case of fluid medicine—be it infusion, decoction or tincture—that has a particularly unpleasant taste, it is sometimes advisable to mask the taste by combining the fluid with a sweetener. One way to do this is to use a syrup, which is the traditional way to make cough mixtures more palatable for children, or any herbal preparation more ‘toothsome’, as Culpepper used to call it.

A simple syrup base is made as follows: pour half a litre (one pint) of boiling water onto 1.1 kilograms (2½ pounds) of sugar, place over heat and stir until the sugar dissolves and the liquid begins to boil. Then take off the heat immediately.

This simple syrup can best be used together with a tincture: mix one part of the tincture with three parts of syrup and store for future use.

For use with an infusion or decoction, it is simpler to add the sugar directly to the liquid: for every half litre (one pint) of liquid add 350 grams (¾ pound) of sugar and heat gently until the sugar is dissolved. This again can be stored for future use and will keep quite well in a refrigerator.

Since too much sugar is not very healthy, syrups are best used for gargles and cough medicines only.

Oxymel

When you have to take a particularly powerful tasting herb, such as Garlic, Squills or Balm of Gilead, the taste can best be covered by making an oxymel, which is made from five parts honey with one part vinegar. To make an oxymel base, put half a litre (one pint) of vinegar and 1 kilogram (2 pounds) of honey into a pot and boil until the liquid has the consistency of syrup.

Dr. Christopher gives the following recipe for the preparation of oxymel of Garlic: put 250 millilitres (½ pint) of vinegar into a vessel, boil in it 7 grams (¼ ounce) of Caraway Seeds and the same quantity of Fennel Seeds. Add 40 grams (1½ ounce) of fresh Garlic Root sliced, then press out the liquid and add 300 grams (10 ounces) of honey. Boil until it has the consistency of syrup.

This oxymel can either be used as a gargle or you can take about two tablespoonfuls internally.

Dry preparations

Sometimes it is more appropriate to take herbs in a dry form, with the advantage that you do not taste the herb and also that you can take in the whole herb, including the woody material. The main drawback lies in the fact that the dry herbs are unprocessed, and therefore the plant constituents are not always as readily available for easy absorption. In a process like infusion, heat and water help to break down the walls of the plant cells and to dissolve the constituents, something which is not always guaranteed during the digestive process in the stomach and the small intestines. Also, when the constituents are already dissolved in liquid form, they are available a lot faster and begin their action sooner.

A second drawback for taking some of the herbs dry, as in capsules, lies in the very fact that you do not taste the herb. For various reasons—even though they taste unpleasant—the bitter herbs work much better when they are tasted, as their effectiveness depends on the neurological sensation of bitterness. When you put bitters into a capsule or a pill, their action may well be lost or diminished.

Taking all these considerations into account, there are still a number of ways to use herbs in dry form. The main thing we have to pay attention to is that the herbs be powdered as finely as possible. This guarantees that the cell walls are largely broken down, and helps in the digestion and absorption of the herb.

Capsules

The easiest way to use dry powdered herbs internally is to use gelatine capsules (which come in various sizes and can be obtained from most chemists. Capsules not made of animal products are also produced. Ask in your area for suppliers). The size you need depends on the amount of herbs prescribed per dose and on the volume of the material. A capsule size 00 for instance will hold about 0.5 grams (1/6 ounce) of finely powdered herb.

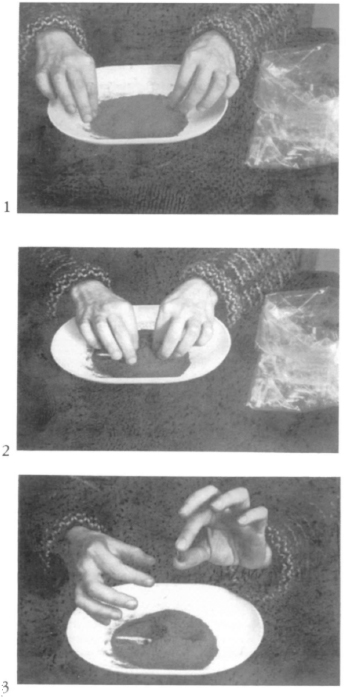

To fill a capsule is very easy:

1. Place the powdered herbs in a flat dish and take the halves of the capsule apart.

2. Move the halves of the capsules through the powder, filling them in the process.

3. Push the halves together.

Pills

There are a number of ways to make pills, depending on the degree of technical skill you possess.

The simplest way to take an unpleasant remedy is to roll the powder into a small pill with fresh bread, which works most effectively with herbs such as Golden Seal or Cayenne. Instead of using bread, the powder can be combined with cream cheese.

You can make a more storable pill by making lozenges, which can be swallowed whole if you cut them to the appropriate size.

Lozenges

The method of making lozenges is based on combining a powdered herb with sugar and a mucilage to produce the characteristic texture. Lozenges are the ideal preparation for remedies to help the mouth, throat and upper respiratory tract as this way they can work where they are most needed.

The mucilage may be obtained from Marhsmallow Root, Slippery Elm Bark, Comfrey Root or from one of the gums such as Tragacanth or Acacia.

This is how to make lozenges using Tragacanth: Bring half a litre (1 pint) of water to the boil and then mix it with 30 grams (1 ounce) of Tragacanth, which has been soaked in water for 24 hours and stirred as often as possible. Then beat the mixture to obtain a uniform consistency and afterwards force the mixture through a muslin strainer. When the mucilage is ready, mix it with the powdered herb to form a paste and, if you feel you need to, add sugar for the taste. Roll the paste on a slab, preferably on marble, which has been spread with cornstarch or sugar to prevent the paste sticking. Cut into any shape and size you like and leave the lozenges exposed to the air until dry. Then store them in an airtight container.

Instead of using dry herbs, you can also use essential oils. A good example would be Peppermint oil. Mix 12 drops of pure Peppermint oil with 60 grams (2 ounces) of sugar and then combine this with enough of the mucilage of Tragacanth to make a paste. Then proceed as above and store the product in an airtight container for later use.

External Remedies

As the body can absorb herbal compounds through the skin, a wide range of methods and formulations have been developed that take advantage of this fact. Douches and suppositories, though they might appear to be internal remedies, have traditionally been categorised as external remedies.

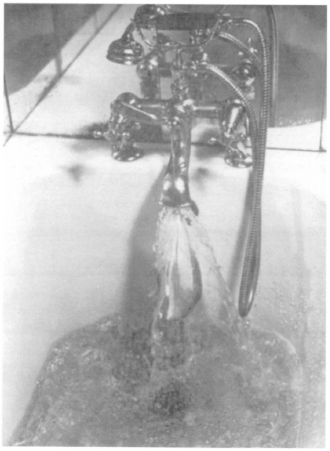

Baths

The best and most pleasant way of absorbing herbal compounds through the skin is by bathing in a full body bath with half a litre (a pint) of infusion or decoction added to the water. Alternatively, you can also take a foot or hand bath, in which case you would use the preparations in undiluted form.

Any herb that can be taken internally can also be used in a bath. Herbs can, of course, also be used to give the bath an excellent fragrance.

To give some idea of herbs that are particularly good to use: for a bath that is relaxing and at the same time exquisitely scented, infusions can be made of Lavender Flowers, Lemon Balm, Elder Flowers or Rosemary Leaves. For a bath that will bring about a restful and healing sleep, add an infusion of either Valerian, Lime Blossom or Hops to the bath water. For children with sleep problems or when babies are teething, try either Chamomile or Lime Blossom, as the herbs mentioned above may be too strong. In feverish conditions or to help the circulation, stimulating and diaphoretic herbs can be used, like Cayenne, Boneset, Ginger or Yarrow.

These are just some of the possibilities. Try out others for yourself. There are also ideas in books about aromatherapy, a healing system based on the external application of herbs in the form of essential oils. These oils can also be used in baths by putting a few drops of oil into the bathwater.

Instead of preparing an infusion of the herb beforehand, a handful of it can also be placed in a muslin bag which is suspended from the hot water tap so that the water flows through it. In this way a very fresh infusion can be made.

Douches

Anther method of using herbs externally is a douche, the application of herbs to the vagina, which is particularly indicated for local infections. Whenever possible, prepare a new infusion or decoction for each douche. Allow the tea to cool to a temperature that will be comfortable internally. Pour it into the container of a douche bag and insert the applicator vaginally. Allow the liquid to rinse the inside of the vagina. Note that the liquid will run out of the vagina, so it is easiest to douche sitting on the toilet. It is not necessary to actively hold in the liquid. In most conditions indicating a need for douching, it is advisable to use the tea undiluted for a number of days three times daily. If, however, a 3 to 7 day course of douching (along with the appropriate internal herb remedies) has not noticeably improved a vaginal infection, see a qualified practitioner for a diagnosis.

Ointments

Ointments or salves are semi-solid preparations that can be applied to the skin. Depending on the purpose for which they are designed, there are innumerable ways of making ointments; they can vary in texture from very greasy ones to those made into a thick paste, depending on what base is used and on what compounds are mixed together.

Marigold

Any herb can be used for making ointments, but Arnica Flower (note that Arnica us not advisable on open wounds), Chickweed, Comfrey Root, Cucumber, Elder Flower, Eucalyptus, Golden Seal, Lady’s Mantle, Marigold Flower, Marshmallow Root, Plantain, Slippery Elm Bark, Yarrow and Woundwort are particularly good for use in external healing mixtures. For the specific use of each herb, please refer to the Herbal section.

The simplest way to prepare an ointment is by using vaseline or a similar petroleum jelly as a base. Whilst this has the disadvantage of being an inorganic base, it also has a number of advantages. Vaseline is easy to handle so a simple ointment can be made very quickly. Besides this it has the advantage of not being absorbed itself by the skin, making it useful for instance as the base for the anti-catarrhal balm described later. Here the vaseline acts merely as a carrier for the volatile oils, which can thus evaporate and enter the nasal cavities without being absorbed through the skin.

The basic method for a vaseline ointment is to simmer 2 tablespoonfuls of a herb in 200 grams (7 ounces) of vaseline for about 10 minutes. A single herb, a mixture, fresh or dried herbs, roots, leaves or flowers can be used.

As an example, here is a recipe for a simple Marigold ointment, which is excellent for cuts, sores and minor burns: Take 60 grams (2 ounces or about a handful) of freshly picked Marigold Flowers and 200 grams (7 ounces) of vaseline. Melt the vaseline over low heat, add the Marigold Flowers and bring the mixture to the boil. Simmer it very gently for about 10 minutes, stirring well. Then sift it through fine gauze and press out all the liquid from the flowers. Pour the liquid into a container and seal it after it has cooled.

In more traditional ointments, instead of using vaseline a combination of oils were used that act as a vehicle for the remedies and help them to be absorbed through the skin, plus hardening agents to create the texture desired. The following example is the prescription for a simple ointment from the British Pharmacopoeia from 1867 for ‘Unguentum Simplex’:

White wax 2 ounces (60 grams)

Lard 3 ounces (90 grams)

Almond oil 3 fluid ounces (90 millilitres) “Melt the wax and lard in the oil on a water bath, remove from heat when melted, add almond oil and stir until cool.”

In this basic recipe, the lard and the almond oil facilitate the easy absorption of the herbal remedies through the skin. Instead of these carriers we can use one or more of lanolin, cocoa butter, wheat germ oil, olive oil and vitamin E. The wax thickens the final product, and for this effect we could also use lanolin, cocoa butter or most ideally beeswax, depending on the consistency we want to achieve.

To make a herbal ointment from a simple base like the one described above involves a number of steps:

1. Make the appropriate water extract, either an infusion or decoction, and strain off the liquid to be used in step 4.

2. Measure out the fat and oil for the base.

3. Mix the fat and oil together.

4. Add the strained herbal extract and stir it into the base.

5. Simmer until the water has completely evaporated and the extract has become incorporated into the oil. Be careful not to overheat the mixture and watch particularly for the point when all the water has evaporated and the bubbling stops. If additional thickeners (like beeswax) need to be incorporated, they can be added at this point and melted with the base, heating slowly and stirring until completely blended.

6. If a perishable base is used (such as lard), a drop of tincture of benzoin should be added for each 30 grams (ounce) of base.

7. Pour the mixture into a container.

Suppositories

Suppositories are designed to enable the insertion of remedies into the orifices of the body. Whilst they can be shaped to be used in the nose or the ears, they are most commonly used for rectal or vaginal problems. They act as carriers for any herb that it is appropriate to use, and there are three general categories of these. Firstly, there are herbs acting to soothe the mucous membranes, reduce inflammations and aid the healing process, such as the root and the leaf of Comfrey, the root of Marshmallow and of Golden Seal, and the bark of Slippery Elm.

Secondly, there are the astringent herbs that can help in the reduction of discharge or in the treatment of haemorrhoids, such as Periwinkle, Pilewort, Witch Hazel and Yellow Dock.

And thirdly there are remedies to stimulate the peristalsis of the intestines to overcome chronic constipation, in other words the laxatives. It will often be appropriate in any of these three categories to include with the above one of the anti-microbial herbs.

As with ointments, we can choose from different bases, keeping in mind that it has to be firm enough to be inserted into the orifice, while at the same time being able to melt at body temperature once inserted, to liberate the herbs it contains. The herbs should be distributed uniformly in the base—particularly important when we are using a powdered herb, the easiest form for this. To prepare a suppository: Mix the finely powdered herb with a good base, preferably cocoa butter, and mould it in the way described below.

A more complex method has to be used when we want to avoid the introduction of powdered plant material into the body: The simplest form of preparing suppositories this way uses gelatin and glycerine—both animal products—and either an infusion, a decoction or a tincture, in the following proportions:

Gelatin | 10 parts |

Water (or infusion, decoction, tincture) | 40 parts |

Glycerine | 15 parts |

The gelatin is soaked for a while in the water-based material and then dissolved with the aid of gentle heating. Then the glycerine is added and the whole mixture is heated on a water bath to evaporate the water, as the final consistency desired depends on how much water is removed. If it is removed completely, a very firm consistency will be achieved.

The easiest way to prepare a mould—for both kinds of bases—is to use aluminium foil which you can shape to the length and shape you need. The best shape is a torpedo-like, one inch long suppository. Pour the molten base into the mould and let it cool; you can then store the suppositories in the moulds in a refrigerator for a while, though it is always preferable to make them when they are needed.

Compresses

A compress or fomentation is an excellent way to apply a remedy to the skin to accelerate the healing process. To make a compress, use a clean cloth—made either of linen, gauze, cotton wool or cotton—and soak it in a hot infusion or decoction. Place this as hot as possible upon the affected area. As heat enhances the action of the herbs, either change the compress when it cools down or cover the cloth with plastic or waxed paper and place on it a hot water bottle, which you can change when it cools.

All the vulnerary herbs make good compresses, as do stimulants and diaphoretics in many situations.

Poultices

The action of a poultice is very similar to that of a compress, but instead of using a liquid extract, the solid plant material is used for a poultice.

Either fresh or dried herbs can be used to make a poultice. With the fresh plant you apply the bruised leaves or root material either directly to the skin or place it between thin gauze. Dried herbs must be made into a paste by adding either hot water or apple cider vinegar until the right consistency is obtained. To keep the poultice warm, you can use the same method as for the compress and place a hot water bottle on it.

When you are applying the herb directly to the skin, it is often helpful first to cover the skin with a small amount of oil, as this will protect it and make removal of the poultice easier.

Poultices can be made from warming and stimulating herbs, from vulneraries, astringents and also from emollients, which are demulcents that are soothing and softening on the skin, such as Comfrey Root, Flaxseed, Marshmallow Root, Oatmeal, Quince Seed and Slippery Elm Bark.

Poultices are often used to draw pus out of the skin and there are a multitude of old recipes. Some of them use Cabbage, which is excellent, others use bread and milk, some even soap or sugar. An old recipe for a Flaxseed meal poultice was as follows: “Mix a sufficient portion of the meal with hot water to make a mushy mass. Spread this with a tablespoon on a piece of thin flannel or old muslin. Then double in a half inch of the edge all round to keep the poultice from oozing out. When it is on, cover it at once with a piece of oiled silk, oiled paper, or thin rubber cloth, to keep the moisture in.”

Liniments

Liniments are specifically formulated to be easily absorbed through the skin, as they are used in massages that aim at the stimulation of muscles and ligaments. They must only be used externally, never internally. To carry the herbal components to the muscles and ligaments, liniments are usually made of a mixture of the herb with alcohol or occasionally with apple cider vinegar, sometimes with an addition of herbal oils. The main ingredient of a liniment is usually Cayenne, which may be combined with Lobelia or other remedies. The following liniment is described by Jethro Kloss (in Back to Eden): “Combine two ounces powdered Myrrh, one ounce powdered Golden Seal, one-half ounce Cayenne Pepper, one quart rubbing alcohol (70 per cent): Mix together and let stand seven days; shake well every day, decant off, and bottle in corked bottles. If you do not have Golden Seal, make it without.” Another excellent liniment that warms and relaxes muscles at the same time is made with equal parts of Lobelia and Cramp Bark plus a pinch of Cayenne. This is made into a tincture or liniment as described above.

Oils

As you can see in the Herbal section of the book, many herbs are rich in essential oils. There are herbs like Peppermint, where the oils are volatile, which makes the plant aromatic, and there are also those whose oils are not particularly aromatic, such as St. John’s Wort.

Herbal oils can be used in two forms, depending on the mode of extraction. First of all there are the pure essential oils, which are extracted from the herb by a complex and careful process of distillation. Only an expert can make these at home. These oils are best obtained from specialist suppliers (see list in the section on suppliers), who distil them as the basis for aromatherapy and as such take care that they are as pure as possible.

The second way of extracting oils is much simpler and resembles the method of cold infusion. Instead of infusing the herb in water, it is put into an oil, whereby we obtain a solution of the essential oil in the oil-base. The best oils to use are vegetable oils such as Olive, Sunflower or Almond oil, but any good pressed vegetable oil can be used and these are preferable to mineral oils.

To make a herbal oil, first cut the herb finely, cover it with oil and put in a clear glass container. Place this in the sun or leave in a warm place for two to three weeks, shaking the container daily. After that time, filter the liquid into a dark glass container and store the extracted oil.

A typical and very nice example of such an oil is St. John’s Wort oil, which makes a very red oil that can be used externally for massages and to help sunburns and heal wounds. It can also be taken internally in very small doses to ease stomach pains. To make it, pick the flowers when they are just opened and crush them in a teaspoonful of olive oil. Cover them with more oil, mix well and put in a glass container in the sun or a warm place for three to six weeks, at the end of which the oil will be bright red. Press the mixture through a cloth to remove all the oil and leave it to stand for a while, as there will be some water in the liquid which will settle on the bottom so that the oil can be decanted. Then store the oil in a well sealed, dark container.