CLIMBING THE BACK TRAIL in his automaton’s stride, Loyal rolled the mountain air through his mouth. The taste of it was a little like the ozone smell that came after a lightning strike. It flared in his lungs, started his morning cough, and he hawked up stone dust.

He heard the jingling sound of Berg’s mule up at the mine entrance. To the west the summit ridge of Copper Peak Bred with red light. The timbers of an old ore tram support reflected violet and rose. The rock blazed orange, splayed black, cut like a deck of cards.

Berg could drive up in his truck if he wanted but he rode the mule, had named it Pearlette after his oldest daughter. Every time he said ‘Pearlette’ Loyal wondered about the little daughter, imagined her as thin and sad, her reddish hair in braids, staring from an attic window onto the road that rolled away to the Mary Mugg. Did the kid mind sharing her name with a mule?

Deveaux, the shift boss, was up at the mine entrance too, squatting off to the side, making a pannikin of coffee. He could get a paper cup of coffee from the canteen, but he liked to do it this way. Showing off his gritty uranium days after the War when he wandered around the Colorado Plateau with a Geiger counter strapped to his back. He let the grounds settle, then drank it black from the pan, soot smearing his mouth, and, as he wiped it away, griming into his pasty skin and yellow beard. With his short neck and hunched shoulders there was something of the vole in Deveaux.

‘I come back to the Mary Mugg,’ he told them in his peculiar voice that was both sweet and grainy, like the meat of a pear, ‘as a relief from them red mudstone beds up on the Plateau, a relief from them headphones. I hear that click-click-click in my sleep.’ He’d returned an earth-colored man, not the miner’s wormy white. He was an old hand, had worked the Mary Mugg through the dirty thirties. When Roosevelt closed down the gold mines during the War Deveaux had gone into the Army as an explosives specialist. The mine opened again in 1948 but by then he was strapped into his Geiger counter, sleeping out uneasily with the coyotes, dreaming of the cool silences underground and the way the bed squeaked when his wife rolled over.

As compact as a jackknife, he’d been dulled by his miner’s life. ‘I spent so many years underground, Jesus Christ, off and on since I was seventeen, I felt like I was peeled down to the meat up on the Plateau. Mrs. Dawlwoody thinks I come back to do her a favor, but I swear to Christ I’d work for nothing, get out from under that sky. I seen red spots in front of my eyes all day long, squint, old eyes start to water and tear. Too bright, too hot, everything watching you. The wind never lets up, like a kid pullin’ at your sleeve all day, “Daddy, buy me some candy.” That’s what I hated about farming. I tried that five years. You set out there all day on the tractor or stringing fence and the wind throws trash in your face, whips your hair in your eyes, knocks your hat into the next county and laughs to see you run for it.’ He put his head down, murmured at his knees, ‘It’s not so bad in the mines. And I missed the old lady. Least I can go home on weekends, sleep comfortable instead of down in the dirt.’

Mrs. Dawlwoody’s maiden name had been Mary Mugg. Limp and elderly, with cold waves of white hair rolling over her ears, she came to the mine each Friday to sit in proprietorial stateliness behind the paymaster as he handed out the checks. Her husband, DeWitt Dawlwoody, was killed before the War in a car accident in Poughkeepsie, New York. He was on a money-raising visit to his cousin, the manufacturer of Kronos time-clocks. The mine needed new machinery. Mrs. Dawlwoody believed the hand of God would show the truth about new machinery. Just before an afternoon storm she had Deveaux set out two pumps on Copper Peak, one ancient hand pump with tandem iron handles, the other a new electric C. J. Brully. Let God speak whether we get new machinery, she said. Yet lightning struck neither pump for a month. At last Deveaux nailed each pump to a post set in the rocks, and then blasted the old one with a little dynamite. Showing the need for new electric pumps. But by then Mrs. Dawlwoody knew it was a stupid game.

The Mary Mugg was a hard-rock mine. An ancient stamp mill broke the low-grade ore, and the conveyor belt dragged it into the sheds where they separated the gold from the glassy rock fragments. Much gold escaped the stamp mills. The big mines had all gone over to the new ball and rod mills. The Mary Mugg wasn’t the kind of mine where high-paid Cousin Jacks worked; those stone-headed Cornishmen were all up in South Dakota at the Homestake, talking the gold out of the rock with their white sunless mouths, bending other miners to their will, making them thrash the metal out of the stone no matter if it drew blood, or they were up in Michigan at the Anaconda, battering the copper loose with their flinty rutting. Coal for hearts, granite for fists, silver-tongued and liked to see blood. None worked at Mary Mugg. They were expensive labor.

The Mugg was a little operation that attracted outlaws and cripples; 30 percent waste, gold and men, Deveaux said. But you never could tell what they might hit, never could tell who’d end up a millionaire governor. That was the trouble, said Berg when Deveaux was out of hearing; they did know. The little Mary Mugg was a cripple herself.

Berg tied Pearlette to a pine and emptied the water bags into her pan. He looked past Loyal without speaking. There was something brutal about Berg though he treated the mule gently and hummed. He had a pale mustache, like two withered beech leaves hanging from his nostrils. The pan had done double service all summer. He used it to wash in before he went down the trail in the evening. Loyal was damned if he’d want to wash up in mule slobber, but Berg had to have his scrub-up. For a man who’d farmed he was fastidious. He claimed his freckled skin plagued him after a day in the stone. Once, on a clear February afternoon with the daylight getting longer, he’d come out at the end of the shift and built a fire on a pile of rocks, then, when the fire was down he raked the coals out and propped up his poles, covered them with a couple of canvas tarps from the mule’s lean-to. The length of his naked legs and arms suggested locomotive drive shafts. They’d watched him burst out of his jury-rigged sauna into the dusk, a luminous pillar of mule-scented steam around him. He got down and rolled in the dry snow until he was as frosted as a sugar doughnut.

‘That’s the scandahoovian for you,’ said Deveaux.

Jugging engine sounds bounced back and forth between Copper Peak and the rock face under the Mary Mugg. Trucks and cars jerked up the grade from Lemon. The turnaround and the parking lot were a hundred feet lower than the mine entrance. Boots clattered on the path, there was a laugh, the sound of coughing and spitting. First their hats showed, then their heads and shoulders, bobbing as they climbed. Loyal could see the shining track of blood already running from Cucumber’s thick nostrils, see the hand holding the blood-stiff staunching rag rise and dab. Nobody could say his unpronounceable foreign name. Cucumber was close enough. Deveaux dropped his cigarette butt, stubbed it with his little shoe, but the smoke still rose upward.

‘Think he’d find some other kind of work if he can’t stand the altitude,’ said Deveaux. ‘Sick of looking at that red snot.’ He said it where Berg couldn’t hear him, dumping his coffee grounds, and wiped the inside of the pot with a wad of grass. He pitched his voice up. ‘Guys on day’s pay, up in the Red Suspenders. Contract guys know where they’re working.’

Berg and Cucumber had worked contract together for two years. Loyal was the new man, come to them from the hourly wage mucking crew. He’d talked to Deveaux.

‘I need a chance to make more money than I’m makin’. Savin’ up for a farm. Put me in with some contract guys, o.k.?’ Could not keep the insolence out of his voice. Letting Deveaux know the Mary Mugg might be here today but gone tomorrow.

‘I don’t know. Those guys choose themselves up pretty much. Anyway, you oughta do all right on what you make – no kids or wife.’ But he’d said something and Berg had nodded.

Berg would talk weather and land and season from his wheat-farm days, telling it all to buffalo-shouldered Cucumber, and the crabbed Friesian would mumble and stumble on about boats and kids and home. He had a bifid thumb, a great wide thing with two dirty nails crowding each other. Silence for Loyal.

Cucumber’s wife rarely gave him enough food to satisfy his incessant hunger. He ate slabs of pork, biscuits, wedges of cheese, then stared hungrily at their sandwiches in the humpbacked lunch boxes, swallowed and licked his mouth like a dog at a picnic. Loyal gave him one of the oatmeal cookies he bought from Dave at the boarding house. Old Dave the accordion and harmonica salesman, who’d done all right, until he got gold fever and took up prospecting. A drunk fall ended in a broken pelvis.

‘What else to do on Sadday night but fall down and break your ass?’ he demanded. The bones had welded back together stiff as metal so that he walked like a trick dog on its hind legs. He’d cook at the Lemon boarding house for the rest of his life. He put piñon nuts in the cookies. ‘An acquired taste like yer lah-di-dah stuffed olives and caviar.’

A few days later Loyal found the cookie on a shelf of stone in the face of the stope. He told himself that Cucumber had laid it there and forgotten it, but remembered some mumbled laughter between Cucumber and Berg on the way out, and a bitter name swelled in his throat. Not good enough for him! The damn foreigner.

Cucumber had a sockful of strange ways. On the way down to Lemon at the end of the shift they’d pull in at Ullman’s Post for beer to sluice the rock dust.

‘Pick me a Red Fox,’ Cucumber mumbled in an offhand voice to the backs climbing out of the car, keeping his money in his pockets with his hands. Somebody would bring one back. And Cucumber would take the beer, rest the cap on the edge of the window frame and knock it off with the heel of his thick hand, drink it in two swallows and sit, looking unfinished, holding the empty bottle between his thighs. Other times he’d charge out of the car and run in, pulling at both pockets, and come back lugging a case of bottles.

‘Take it. Take it! Don’t insult me, say no!’

And Loyal had seen him fight a man who wouldn’t drink.

Down in the stope the mine door was damp, the rucked dust tracked with footprints. The rock walls glistened. Their clothes, worn cotton denim, hung in weak folds. They listened to the faint creaking of the timber supports. The ventilator snored. Berg began to bar down, prying off loose ceiling rock that might hang overhead after yesterday’s blasting. The muckers had hauled out the ore on the second shift. As he worked, small chunks of rock showered onto the rubble, then a big slab, two hundred pounds of rock, smashed down, thrashing dust.

‘Jesus, that give you a godalmighty headache,’ Berg laughed and kept prying. The rock creaked.

‘That, that damn rock’s the main reason you want to work with a Cousin Jack,’ said Berg to Cucumber for the hundredth time. ‘They understand the ore, the rock, like it was talking to them. And when they say she’s not right, you better listen, because they know. I worked with this guy, Powys, in the Two Birds up in Michigan. Copper mine. My first job after I lost the farm. 1936. Wet, dirty, didn’t pay nothing, dangerous as hell. Powys was smart. I don’t know what he was doing in the mines. He could of been anything. Come from Cornwall. He’d quote old Shakespeare, poems. Said he’d mined since he was old enough to put his pants on by himself. Funny about them guys, how smart some of ’em are, read Latin, talk philosophy and still they go down in the mines long as they last. Oh, we was in there, drilling, you know, and there come this little cricking sound like somebody was tearing cardboard, nothing you’d pay any attention to. Powys yells, he yells—’

‘Berg, I hear this two, three hundred times. This the one he gets away by big farts? Or the one he holds up the roof with one hand and picks his nose with the other?’

‘Yeah,’ said Berg. ‘Well, let’s make some money. We got to push it today.’ Light from the yellow headlamp twitching over the rock. Loyal wore his respirator for a little while, but the awkward thing, like a rubber snout, got in his way and he let it dangle around his neck. What the hell, two guys working together, one would wear his mask every day and still get silicosis, the other never bothered and was fine. He’d seen it.

The familiar smell of wet rock, the metal taste of the charged air, the burr of the drill, the rows of deep holes extending along the rock face blurred into dim, chilled hours. Loyal looked over at Berg. Even in the mushroom-colored cone of the miner’s light he could see Berg talking to himself again. Berg had quarter-turned ideas. He believed dead miners came back from hell to the mines where they’d died, and loitered just out of sight in their faded, mangled bodies, and that sometime, if he whirled, he would catch a glimpse of some old rock rat out of the flames on a day’s excursion, posturing behind his back and pointing ironically in the direction of riches. He did that, sometimes, jump and whirl.

‘Goin pretty good?’ Loyal asked. They’d answer if he spoke first.

‘Well, lot of holes, anyhow. We’ll see tomorrow after it comes down. They ought to regrade this rock pretty soon, next week, maybe. The stuff we been seeing, I’d say they ought to grade us up to high B.’

‘I was thinking of quitting this in a couple of months,’ said Loyal. ‘Maybe try what Deveaux was doing, the uranium stuff. I got to get back outside bad as he wanted to get into the mine again. I get a feeling down here in the everlasting Christly dark.’

‘Something to that. Guys used to spend time outdoors, trapping or in the woods, they never feel good in the mines. You’re lucky you got no family. It’s kids keep you in the mine. I always thought I’d hit it, tap some sweet vein, but everything pinched out on me and here I am for life, prob’ly, working in the mines. Hey, Cucumber, Deveaux ever tell you why he quit uranium prospecting?’

Berg gave in too easy, thought Loyal.

Cucumber gobbled in his lumpy accent. ‘Heard it two ways. Heard he didn’t like country. New Mexico, Colorado, Monument Valley, Arizona, Utah. The stuff in the sandstones.’

‘Carnotite. Christ, there’s guys made millions.’ Loyal loved thinking about it, the search, the lucky strike, do what you want with the rest of your life. ‘How about Vernon Pick a couple of years ago? Nine million.’

Berg knew something. ‘Deveaux found a petrified log. It was almost pure carnotite. He made over thirteen thousand on just that one.’

‘Even if you don’t hit a big one. The government says they’ll guarantee a fixed price until 1962. There’s ore-buying stations all the hell over the place. Christ, there’s bonuses, they’ll practically stake you, give you all the help in the world.’

‘I was to make that kind of money I’d go up the northwest coast, buy me a boat and fish. Big sea salmon.’ A flickering of longing, a much-kinked wire in his talk.

Cucumber gave his pumping laugh. ‘You in boat? Only one kind of boat for you, Berg. Rowboat. Rowboat in harbor.’

‘What the hell do you know about it?’

‘Know boats good. Born on the boats. Born on Spiekeroog. You don’t know this place. Fishing boats. I worked passenger liners. Before the War.’

‘Bet you worked the Titanic, didn’t you? God, I’d ride a case of dynamite down the Yellowstone before I’d ride on a boat that you was steering, Cucumber.’

‘What’d Deveaux do with his money? The son of a bitch was rich,’ said Loyal. Furiously. The drill bucked and chewed on stone, spit dust.

‘Different stories. One thing I heard, heard he give it to Mrs. Dawlwoody, bought into the Mary Mugg. I also heard he lost it all in one hour in a blackjack game in Las Vegas. Cucumber, you ever been to them casinos?’

‘Hell, no. I got trouble makin’ it, never mind lookin for ways to throw it out.’ He went into a long coughing spell. There was a light patter of rock flakes somewhere behind them.

‘No good,’ said Cucumber. ‘Wasn’t barred down good. She don’t flake off when she’s barred down good.’ He tapped very lightly on the roof with a bar.

‘She’s barred down,’ said Berg. ‘Hey, why the hell did you ever leave Squeaky-Gut or whatever the hell it is?’

‘Island. Island in North Sea. I work on boats, o.k.? Do it for years. Happy. One day I go by fortune teller in Oslo, what they call a dukker. She say, “You die by water.” She know those things. So I come America, work in the mines.’

‘You believe that shit?’

‘Yeah, Berg, believe it. This dukker tell this guy worked on the ship, “Watch out for wine.” He laugh. He don’t drink only water, tea, coffee. In Palermo they loading, Jesus, falls on him a crate. This crate full of wine. You bet believe it.’ But did not tell deeper reasons.

‘Dinner whistle,’ said Berg, imitating the hoarse shriek of a factory whistle. They sat together under Berg’s wall. He could imitate the mule, horses, any model of car at any speed when he felt like it.

‘Hey, what’s the government pay for uranium, anyway?’

‘Heard the guaranteed maximum is seven dollars twenty-five cents a pound. How many pounds per ton depends on the strike. There’s an average of four pounds to the ton. There’s a rich Canadian strike paid out eighty pounds. I got a article in a magazine, Argosy, you want to look at it.’ Loyal shined the light over the ranks of holes drilled twelve feet into the rock.

‘Goin’ pretty good. Guess Berg’ll get his rowboat.’

‘Yeah, and you get your farm. If you’re still crazy enough to want one.’

‘I just want a little place I can work myself.’

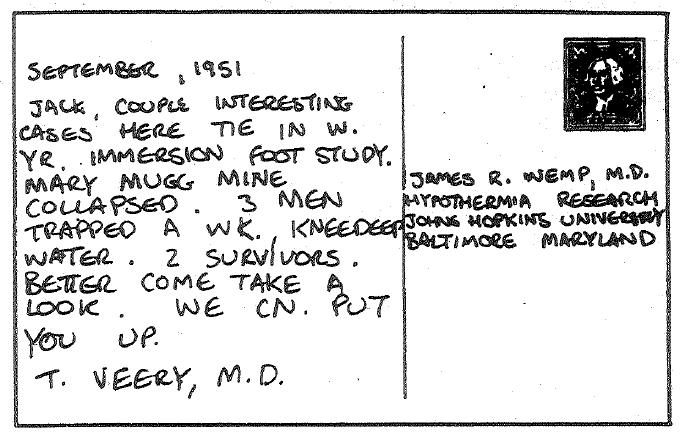

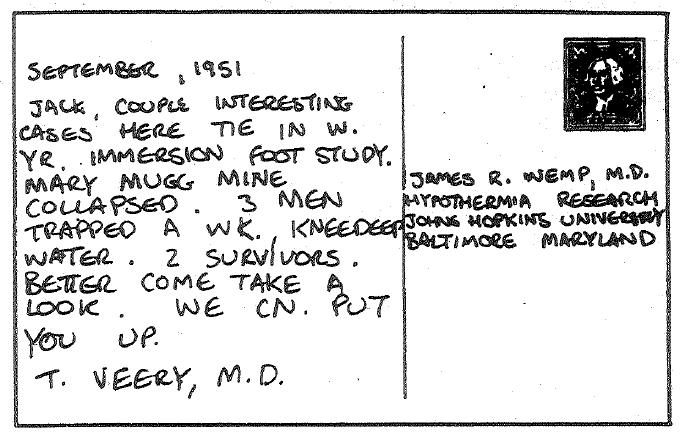

‘No such animal,’ said Berg, opening his lunch box and taking out the thermos. As he unscrewed the threaded cup they felt the floor heave beneath them, followed by a roar as the tunnel leapt into itself. The floor bucked. There was the choking dust and the tinkle of Berg’s thermos cup hitting the rock.

Cucumber’s headlamp smashed against the wall and went out. Loyal lay on his back, dust and rock flake raining onto him. Berg was swearing, his light swinging from side to side as he looked around. An icy coldness seized Loyal and he wondered if his spine was snapped; he’d heard there wasn’t much pain with a broken back; you went cold and numb. You couldn’t move. He didn’t want to try to move. Berg was splashing around, cursing, shining his light over the cave-in rubble. There was a terrible moaning. Loyal thought it was Cucumber, then knew it was coming from the ventilator as thousands of tons of rock settled on the pipe.

‘Cucumber. You o.k.? Blood?’

‘Dropped my porkchop,’ said Cucumber. ‘Porkchop down in water.’

Loyal understood then that the cold numbness was an inch of icy water, that he was lying in it.

‘Jesus Christ, where’s the damn water coming from?’ His voice sounded panicky. He got up, stood shuddering. Nothing was broken. The water was up to his ankles and his back was sopping wet. His knees stung.

The water came from everywhere. It limped and trickled from the ceiling and walls in thousands of tiny drops like sweat, fed in streams; it welled up underfoot.

‘Jesus, Jesus, Jesus,’ moaned Cucumber. ‘Ah, Jesus, drown in dark. Water.’

‘We don’t know how bad it is. They could be o.k. up there, be tryin’ to get us out right now.’ Berg’s voice was tense but controlled. They stifled their ragged breaths, listened for the chinking sound of hammers. The rock creaked. The heavy drops fell and fell, echoing in the flooding stope. Loyal felt a calm. Was it to be by drowning or crushing? Under the rock.

Berg had been in cave-ins before. He knew the drill. ‘We save our batteries. Don’t turn on your lamp. They’d last us a few days.’

‘Days!’ choked Cucumber.

‘Ah, you old son of a bitch, you can live for weeks in a cave-in as long as you got water. And have we got water. Let’s move up to the high end of the stope. Get out of the slop good as we can.’

They waded up the floor of the stope in the dark until they reached a band of dry rock at the end where they’d drilled in the morning. By groping with their hands they felt the beach of dry floor was about three feet wide, barely enough to sit down on. Loyal fished string out of his pocket and knotted off the measurement. Berg felt for the tools. The water rose gradually. All around them the patter of falling water, the deadly uniting and tonking. The water crept up the dry strip.

‘This stope is thirty foot high. It take one hell of a lot of water to fill this up,’ said Berg.

‘Yeah, what you do, climb up walls like fly and stay up? What you do, swim around? Have water race? I tell you what you do, is Dead Man’s Float. Nobody never open this up. Standing in grave, Berg. I told you, take third man, bad luck. Now you see!’ Cucumber’s voice was raw. He spit and gobbered in the dark as though Berg had tricked him into this deadly hole.

They stood with their backs to the wall, facing the water. Loyal tried not to lean against the wall. The rock sucked the warmth out of the body. When his legs knotted, he squatted down. By stretching out his hand he could feel the edge of water. The hours went along. Cucumber sucked and chewed at something. He must have found the porkchop.

‘Better save your food. We don’t know how long we’ll be down here,’ said Berg. Sullen silence from Cucumber.

Loyal woke up in a swooning fright, legs numb with pins and needles, knees billets of wood with wedges driven deep. Cucumber was bellowing what, a song, in another language. Loyal put out his hand to steady himself and there was an inch of water. It was up to the wall.

‘Berg. I’m going to put on my light. See if there’s a dry place.’ He knew there was no dry place. The headlamp’s wavering light reflected from the sea that stretched before them to where the rockfall choked the passage. Before he shut the light off again he turned it on Cucumber who leaned his forearms against the wall and pressed his head against his wet hands. The water seeped into his boots. The leather was black with wet, shone like patent leather.

‘Save the fucking light,’ Berg shouted at him. ‘You’ll kill for a light in a couple of days. Sense of wasting it now?’

There was no way to tell how long it had been since the cave-in without switching on the light. The only one with a watch was Berg. The water came over the tops of their shoes. Loyal felt his feet swelling in the slimy leather, packing the boots tight with stinging flesh. Their calves knotted, the muscles twitched against the cold. There was a raiding sound and he thought it was rock flakes before he reasoned that rock flakes would slip into the water as silently as knives. A little later he knew what the rattling was; Berg’s and Cucumber’s teeth, and he knew because the chills were racking him too, until his whole body shuddered.

‘It’s the cold of the water drawing the heat out of our bodies. The cold will kill you before you drown,’ Berg said. ‘If we can find the tools, a hammer and a chisel, we got a chance to cut out some stone and stand on it, nick out some steps or something, get up out of the water.’ They groped under the water along the wall where they had been working. The useless drills were there. Then Loyal’s lunch box, full of mushy waxed paper and bread pulp, but the slices of ham were still good and he ate one, put the other in his jacket pocket. The stone hammers, chisels and bits were in a wooden carpenter’s box with an ash dowel for a handle. They all knew it intimately, but it could not be found, even when they waded out to their knees, kicking cautiously along the bottom.

‘Even if I walked into it I couldn’t feel it,’ said Loyal. ‘My feet hurt so Christy much I can’t tell if I’m walking or standing still.’

‘Carry it in,’ said Cucumber. ‘Feel it on arm. Don’t know where put it down. Back by the rail line, maybe. Remember almost trip on it.’

Loyal felt the weight of settling rock above them, half a mile.

Cucumber mumbled. ‘Could be there. Maybe I think we don’t need today.’

In the darkness their eyes strained, unseeing, in the direction of the rail line and the tool box, buried now under the rock. The red motes and flashes that trace through total darkness skidded before them. The water rose slowly.

After a long rime, surely eight or ten hours, he thought. Loyal noticed that the pain in his feet and legs had eased to a cold numbness that crept up toward his groin. He leaned, half-fainting, against the wall because he could hardly stand. Berg was retching in the darkness, and between spasms shook so violently his voice jerked out of him ‘eh-eh-eh-eh-eh.’ Cucumber, on the other side of Berg, in the wet blackness, breathed hard and slow. A steady drip fell near him.

‘Berg. Switch on your light and tell us the time. It’ll help to keep some track of the hours.’

Berg fumbled with his crazy hands and got the switch on but couldn’t read the time on his dancing, leaping watch.

‘Christ,’ said Loyal, holding the jerking arm and seeing ten past two. Which two? Two in the morning after the cave-in or twenty-four hours later, the next afternoon?

‘Cucumber, you think it’s afternoon or 2 A.M.?’ And looked at Cucumber spraddled, arms pressed against the rock to take the weight off his feet, head down. Cucumber turned his head toward the light and Loyal saw the blood tracking from black nostrils, the wet shirt shining with blood, the water around Cucumber’s knees washed with blood. Cucumber opened his mouth and his pale tongue crept from between his bloody teeth.

‘It’s easier for you. You got no babies.’

Loyal turned the light off and there was nothing to do but stand and wait in a half swoon, listening to Cucumber bleed out drop by drop.

And now he knows: in her last flaring seconds of consciousness, her back arched in what he’d believed was the frenzy of passion but was her convulsive effort to throw off his killing body, in those long, long seconds Billy had focused every one of her dying atoms into cursing him. She would rot him down, misery by misery, dog him through the worst kind of life. She had already driven him from his home place, had set him among strangers in a strange situation, extinguished his chance for wife and children, caused him poverty, had set the Indian’s knife at him, and now rotted his legs away in the darkness. She would twist and wrench him to the limits of anatomy. ‘Billy, if you could come back it wouldn’t happen,’ he whispered.

He came awake with a shout, dipping into the water. He could not stand. His clubbed feet could not feel the ground. He knew he had to get the bursting shoes off, the leather that clamped the flesh, the tightening strings, if he had to cut them off. He crouched, gasping, in the water and felt his right shoe. The puffed leg bulged over the top of the shoe. He pulled at the laces underwater, worrying the wet knots, racked with shudders. After a long time, hours, he thought, he pulled the lace free of the eyelets and began to lever at the shoe. The pain was violent. His foot filled the shoe as tight as a piling rammed into earth. Christ, if he could see!

‘Berg. Berg, I got to put on my light. I got to get my shoes off. Berg. My feet’s swole up wicked.’

Berg said nothing. Loyal switched on his headlamp and saw Berg leaning against the wall, halfsagged into a tiny shelf where his knees rested, bearing some of his weight.

He could barely see his shoes under the cloudy water, eighteen inches deep now, and the shoe would have to be cut off. He stood up and switched the headlamp off while he fumbled for the knife in his pocket. It was hard to open it, and harder to sit back down in the water – fall down – and cut the tight leather open. He used the lamp as little as possible while he sawed and panted and moaned. At last the things were off and he threw them out into the blackness, the soft splashes, Berg to his left groaning. His feet were numb. He could feel nothing.

‘Berg. Cucumber. Get your shoes off. Had to cut mine off.’

‘Eh-eh-eh-eh-eh-too-eh-eh-eh cold,’ said Berg. ‘Fucking eh-eh-eh-eh freezing. Can’t.’

‘Cucumber. Shoes off’ Cucumber didn’t answer but they could hear the blood falling into the water.

blood bloodblood blood blood bloodblood

It became difficult to talk, to think. Loyal had long, sucking dreams that he struggled to leave. Several times he thought he was sitting in a rocking chair beside the kitchen stove, and that a child was leaning asleep against his heart, light hair stirring in the whistling wind from his nostrils. He ached with the sweetness of the child’s weight until his mother stirred the fire, and said in an offhand way that the child was not his, it was Berg’s daughter, that these things had been torn from his life like calendar pages and were lost to him forever.

Then he would rouse Berg for the time, but the headlamps were dim and it always seemed to be ten past two.

‘Stopped,’ said Berg. ‘Watch eh-eh-eh stopped.’

‘How long we been in here do you think?’ He only talked to Berg now. He stood close to Berg.

‘Days. Five or eh-eh-eh four days. If you hear them we got to tap, let them guys know we’re still alive down here. Pearlette. Hope they-eh-eh-eh-eh-ey taking care.’

‘Pearlette,’ said Loyal. ‘She your only kid?’

‘Three. Pearlette. James. Abernethy. Eh-eh call Bernie for short. Baby. Sick every winter.’ Berg directed his feeble light at the wall. The water had gone down two inches. ‘We got a-eh-eh-eh chance,’ said Berg. ‘Anyway we got a chance.’

The dying headlamps pointed in Cucumber’s direction showed nothing. They called, with clacking jaws, but he didn’t answer. Cucumber was beyond the circle of light, silent.

When at last the sound of faraway tapping came they struck wet rocks against the wall and wept. Away in the darkness Cucumber rolled in eight inches of mine water, his mouth kissing the stone floor again and again as if thankful to be home.