6

Normalcy and the Black Sox Scandal (1904 to 1922)

progressivism persisted until 1920, but President Woodrow Wilson’s reform agenda at home was interrupted by the outbreak of World War I. In April 1917, less than a month after he began his second term, Wilson asked Congress to declare war on Germany, and he used Progressive methods to manage the war. To convert the peacetime economy to one producing supplies for the war, Wilson created the War Industries Board. He also imposed travel restrictions to prevent precious resources from being wasted on unessential movement, and signed laws that made it illegal to write or utter statements denigrating the flag, the Constitution, or the military. Thousands of pacifists, socialists, and union members were arrested for opposing the war. By the time the war ended in November 1918, the carnage was horrific. The United States lost 110,000 soldiers in battle and another half million to the Spanish influenza. Wilson traveled to France when the war ended to promote his Progressive solution for keeping peace: a list of fourteen demands for the postwar world that included a provision for a League of Nations, an organization to prevent future wars. At home, though, many Americans—believing it violated the United States’ traditional role of neutrality, national sovereignty, and Congress’s authority over foreign policy—opposed the League. The Senate refused to ratify the treaty. Wilson took to the road to promote the treaty, but while in Pueblo, Colorado, the president suffered an incapacitating stroke. In 1919 the country suffered a series of crises that rocked the nation. Labor unrest increased as 20 percent of workers went on strike to protest wages that had stagnated due to wartime controls. Racial tensions escalated. Four hundred thousand African Americans fought in World War I, and many of them expected improved race relations when they returned home. Instead the number of lynchings increased in the South. In Chicago a five-day riot broke out in July when African American teenagers in Lake Michigan swam too close to a white-only beach. When the violence ended, twenty-three African Americans and fifteen whites were dead. Americans also experienced an upswing in anticommunist anxiety with the outbreak of the Red Scare, which was fueled by fear over the 1917 Russian Revolution. Racism also drove the Red Scare, as many white Americans accused Communists of stirring up racial unrest in the country. Thirty states and Congress passed laws that either made it a crime to criticize the government or to promote “radical” movements such as communism, socialism, and anarchism. Under the direction of Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer, the Justice Department arrested more than four thousand people who were accused of being revolutionaries, holding many of them in jail for weeks without charging them with a crime. More than five hundred leftists who were not citizens were deported. Progressivism had ended, and by 1920 Americans sought a “Return to Normalcy” under President Warren Harding, a Republican. Instead he ushered in an era of corruption and troubled morals. In 1920, Prohibition banned the sale and manufacture of alcohol in the United States, which gave rise to bootleggers and organized crime. Scandals also rocked the highest levels of government. A poor judge of character, Harding often appointed associates who sought to personally benefit from their position. One swindled the nation’s Veterans’ Bureau, while another sold off the country’s oil reserves, held for national security purposes, in the infamous Teapot Dome affair. As punishment for this notorious crime, Secretary of the Interior Albert Fall became the first cabinet officer in American history to go to jail. In this tense atmosphere, baseball faced its own scandal—one that nearly destroyed the sport.

On a hot afternoon in Anderson, South Carolina, in 1908, the local minor league baseball team, the Anderson Electricians of the Class-D Carolina Association, hosted a doubleheader against the Greenville Spinners. During the first game, Spinners center fielder Joe Jackson, a twenty-year-old country boy from Pickens County, South Carolina, complained that his brand-new spikes, which he had not yet broken in, were causing blisters to form on his feet. Between games Jackson discarded the shoes and played the second half of the doubleheader in his stocking feet. In the seventh inning of the nightcap, Jackson walloped a triple. As he was pulling into third, an Anderson fan noticed Jackson’s feet and shouted out, “You shoeless sonofagun!” A reporter for the Greenville News overheard the comment and immortalized it in his newspaper story. Although he never again played baseball in his socks, the young man forever became known as Shoeless Joe Jackson.

Jackson, who put together a .346 batting average with Greenville, quickly developed into the top player in the Carolina Association. By midsummer he had caught the attention of Connie Mack, the owner and manager of the Philadelphia Athletics, and on August 24 Jackson played his first game for the A’s. An unsophisticated and illiterate country boy from rural South Carolina, Jackson had trouble adjusting to cosmopolitan Philadelphia. Twice before the end of the season, he abandoned the team and headed home. For the next two years Jackson bounced back and forth between Philadelphia and the minor leagues. At the end of the 1910 season, the Athletics sold him to Cleveland, and Jackson blossomed in the more tranquil midwestern environment. He hit .387 in 1910, .408 in 1911, and .395 in 1912. Both the Washington Senators and the Chicago White Sox wanted Jackson, and in 1915 Charles Comiskey convinced Cleveland to trade him to the White Sox for three journeymen players and $31,000 in cash. Jackson thrived in Chicago. He led the White Sox to a World Series championship in 1917 and to another American League pennant in 1919, and he put together a .356 lifetime batting average, an accomplishment surpassed only by Ty Cobb and Rogers Hornsby. In 1919, however, Jackson and six of his teammates threw everything away, agreeing to take money from gamblers in exchange for losing the World Series. The episode was the biggest scandal ever to rock baseball, and it instigated major reforms in the game.

The order Ban Johnson had brought to baseball in the first decade of the twentieth century began to unravel in the 1910s and, with the disclosure that the 1919 World Series had been fixed, collapsed completely by 1920. Progressivism also broke down in that decade. With the outbreak of World War I, the United States entered a period of uncertainty in the mid-1910s, which devolved into turmoil when the war ended. The Black Sox Scandal, as the 1919 World Series fix was called, occurred at that low point.

With the stability brought by the establishment of the National Commission, the game had grown in popularity in the first two decades of the twentieth century. The annual World Series captured the public’s attention. During the early years of the century, baseball was played during the day, and without radio or television to relay the news of the game, baseball fans would gather in public places, usually outside of newspaper offices, to follow the World Series. Newspapers set up large boards, visible from the street, that featured pictures of baseball diamonds and images of base runners. As the out-of-town results were telegraphed to the newspaper, the images of base runners were advanced or removed from the diamond to indicate what was happening in the game hundreds of miles away.

Baseball players enjoyed unparalleled popularity in the early twentieth century. Stars like Detroit Tigers center fielder Ty Cobb, Boston Red Sox center fielder Tris Speaker, Pittsburgh Pirates shortstop Honus Wagner, and New York Giants starting pitcher Christy Mathewson became household names.

The Chicago Cubs, as the National League entry in America’s second- largest city was now called, dominated the first decade of the twentieth century. Led by its star-studded infield—which featured Frank Chance at first base, Johnny Evers at second base, Joe Tinker at shortstop, and Harry Steinfeldt at third—the Cubs won four pennants between 1906 and 1910. The most exciting pennant race of the era took place in 1908. On September 23, with about two weeks left in the season and the Cubs and Giants locked in a virtual tie for first place, Chicago and New York convened at the Polo Grounds for the third game of a four-game series. With the game tied 1–1 with two outs in the bottom of the ninth inning, the Giants had runners on the corners: Moose McCormick at third and Fred Merkle at first. Giants shortstop Al Bridwell hit a single to center field, which scored McCormick. Merkle, who was running from first to second, saw McCormick cross the plate and assumed the game was over. Before arriving at second, Merkle turned and ran for the dugout, which was common practice at the time when the winning run scored in the bottom of the ninth inning. Recognizing that the game was not yet over, Cubs second baseman Johnny Evers, who spent his spare time reading and rereading the baseball rule book, called for the ball. After a delay of several minutes, Evers received the ball and stepped on second. Then Evers pointed out to umpire Hank O’Day that McCormick’s run did not count because the third out of the inning had been a force out. After some thought, O’Day acknowledged that Evers’s understanding of the rules was correct. He declared the inning over and the score still tied at one run apiece. Because it was getting dark—and because the New York faithful, believing the Giants had won, had stormed the field—O’Day called the game a one-run, nine-inning tie. If necessary, the game would have to be replayed at the end of the season.

The season ended on October 7, with New York and Chicago possessing identical 98–55 records. The two teams again took the field at the Polo Grounds on October 8 for what was essentially baseball’s first tie-breaking play-in game, but in reality was a regular season makeup game. This time the Cubs won, 4–2. Chicago went on to defeat the Detroit Tigers, four games to one, in the 1908 World Series. It would be 108 years before the Cubs would win another World Series.

The Cubs won the National League pennant again in 1910, only to lose the World Series to Connie Mack’s Philadelphia Athletics. Mack, who would own the A’s during the team’s entire fifty-four-year tenure in Philadelphia and would manage the team during its first fifty years, was establishing a new dynasty in Philadelphia. Between 1910 and 1914, the Athletics won four American League pennants and three World Series championships. The Athletics lost the 1914 World Series to the Boston Braves. Boston had been in last place in the National League on July 4, but in the second half of the season, the “Miracle Braves” got hot. Boston leapfrogged the rest of the National League, finishing the season in first place. In the World Series that fall, Boston defeated Philadelphia in four games, becoming the first team ever to sweep a World Series. After its 1914 World Championship, the Braves returned to mediocrity. New England fans, however, still had a reason to cheer, as the Boston Red Sox dominated baseball during the rest of the decade, winning the 1915, 1916, and 1918 World Series.

As the popularity of baseball soared, the first real stadiums appeared. In the nineteenth century, ballparks made with wooden grandstands were always in danger of being destroyed by fire. The new twentieth-century stadiums, made of steel and concrete, were fireproof. Starting with Forbes Field in Pittsburgh, twelve major league clubs constructed new stadiums between 1909 and 1915.

Baseball was so lucrative in the early twentieth century that its success undermined its stability. In 1913 a new six-team minor league, called the Federal League, emerged. Following the end of the season, a wealthy Chicago coal dealer named James A. Gilmore took control of the league and attempted to turn it into a major league. Gilmore recruited wealthy businessmen to own Federal League clubs. Ignoring the reserve clause, the Federal League attempted to sign major league players. The existing major league teams retained most of their players, but had to offer generous salary increases to do so. Still, the Federal League managed to lure a few major leaguers, including Joe Tinker, who became the player-manager of the Chicago club, and Mordecai Brown, who became the player-manager of the St. Louis club. As a self-proclaimed major league circuit, the Federal League operated in 1914 with eight clubs: four in cities that had American or National League teams—Brooklyn, Chicago, Pittsburgh, and St. Louis—and four in top-level minor league cities—Baltimore, Buffalo, Indianapolis, and Kansas City. Competition was especially stiff in Chicago and St. Louis, which boasted clubs in all three leagues.

Table 6.1. Major League Stadiums Built between 1909 and 1915

|

Stadium |

City |

Team |

Year Built |

|

Forbes Field |

Pittsburgh |

Pirates |

1909 |

|

Shibe Park |

Philadelphia |

Athletics |

1909 |

|

Sportsman’s Park |

St. Louis |

Browns |

1909 |

|

White Sox Park (Comiskey Park) |

Chicago |

White Sox |

1910 |

|

National Park (Griffith Stadium) |

Washington |

Senators |

1911 |

|

Polo Grounds |

New York |

Giants |

1911 |

|

Redland Field (Crosley Field) |

Cincinnati |

Reds |

1912 |

|

Fenway Park |

Boston |

Red Sox |

1912 |

|

Navin Field (Tiger Stadium) |

Detroit |

Tigers |

1912 |

|

Ebbets Field |

Brooklyn |

Dodgers |

1913 |

|

Weeghman Park (Wrigley Field)* |

Chicago |

Whales (FL) |

1914 |

|

Braves Field |

Boston |

Braves |

1915 |

* The Chicago Cubs moved into Weeghman Park in 1916.

Unlike the Union Association of 1884 or the Players’ League of 1890, the Federal League did not disband at the end of the season. Instead the league entered the 1915 season with one change. Although Indianapolis had won the 1914 Federal League pennant, Harry Sinclair, an Oklahoma oilman later implicated in the Teapot Dome scandal, moved the team to Newark, New Jersey, in order to tap into the lucrative Manhattan market on the other side of the Hudson. Suffering financial losses, clubs in all three leagues cut ticket prices; a few Federal League teams admitted fans for as little as a dime. In January 1915 the Federal League filed a lawsuit accusing the major leagues of violating the Sherman Antitrust Act. The judge in charge of the case, Kenesaw Mountain Landis, had a history of ruling against monopolies. But Landis, an avid baseball fan and supporter of the Chicago Cubs, allowed the case to languish on the docket while the Federal League slowly bled to death. When the 1915 season ended, the Kansas City club, unable to pay its debts, went out of business. The rest of the Federal League entered negotiations with the major leagues. The American League allowed Phil Ball, the owner of the Federal League’s St. Louis team, to purchase the Browns, while the National League allowed Chicago Whales owner Charles Weeghman to buy the Cubs. Weeghman moved the Cubs into Weeghman Park, the ballpark he built for the Chi-Feds. Renamed Wrigley Field in 1927, it remains one of the oldest major league ballparks; the Cubs still play there today. Major League Baseball offered a $600,000 settlement to the other Federal League clubs. Angry at being denied the opportunity to purchase the St. Louis Cardinals and move them to Maryland, the owners of the Federal League’s Baltimore Terrapins rejected the offer. Instead they filed their own antitrust lawsuit, which would eventually reach the Supreme Court in 1922.

Table 6.2. The Federal League, 1914–1915

|

Federal League in 1914 |

Federal League in 1915 |

|

Baltimore Terrapins |

Baltimore Terrapins |

|

Brooklyn Tip-Tops |

Brooklyn Tip-Tops |

|

Buffalo Blues |

Buffalo Blues |

|

Chicago Whales |

Chicago Whales |

|

Indianapolis Hoosiers |

Newark Peppers |

|

Kansas City Packers |

Kansas City Packers |

|

Pittsburgh Rebels |

Pittsburgh Rebels |

|

St. Louis Terriers |

St. Louis Terriers |

The Federal League’s corpse was hardly cold when baseball encountered a new challenge. In April 1917 America had been drawn into World War I. Major league owners recognized their dilemma: The entire country had been put on wartime footing, and baseball seemed frivolous. Major League Baseball attempted to gain goodwill in wartime by selling war bonds. It also staged exhibition games, with the money going to the war effort. Such games were often played on Sundays. Although many states prohibited professional baseball games on the Sabbath, benefit games were exempt from the restriction. Major League Baseball hoped that if fans became accustomed to attending ball games on Sundays, the restriction might be lifted when the war was over. To boost morale, many baseball clubs had their players conduct military drills before games, but the ballplayers looked silly marching in baseball uniforms and carrying their bats as if they were guns. The Brooklyn Dodgers, realizing how ridiculous this looked, refused to do it.

Many major leaguers served in the war. In October 1918, former Giants’ third baseman Eddie Grant became the first major league player to die in the war; he was killed in the Argonne Forest in France. In 1921 the Giants erected a monument in Grant’s honor in deep center field at the Polo Grounds. Giants pitcher Christy Mathewson, a member of the army’s Chemical Warfare Service, also became a casualty of the war. During training, Mathewson became exposed to poison gas and, with his respiratory system weakened, developed a fatal case of tuberculosis.

Pressure mounted on baseball to shut down. In May 1918 General Enoch Crowder, the head of the Selective Service System, issued a “work or fight” order, which required men not serving in the military to work in the defense industry. Following the edict, club owners decided to end the season on September 1, a month early. The World Series opened on September 5 in Chicago, with the Cubs hosting the Red Sox. When Boston won the series six days later, no one knew if baseball would return the following year.

The war ended in November, and as the 1919 season approached, club owners expected good things. Baseball again had the full attention of the country, and club owners intended to milk it for all it was worth. On September 2, with a month left in the season, the National Commission decided to extend the World Series to a best-of-nine format. Few thought the Cincinnati Reds, who had won their first National League pennant, had a chance in the Fall Classic. The Reds appeared to be overmatched by the American League pennant–winning Chicago White Sox. The White Sox included two future Hall of Famers on their roster: third baseman Eddie Collins and catcher Ray Schalk. The team also boasted Shoeless Joe Jackson, the player with the third-highest lifetime batting average, and the Sox’s pitching staff featured two twenty-game winners: Eddie Cicotte, who won twenty-nine games while only losing seven, and Lefty Williams, who finished the season with twenty-three wins and eleven losses.

Although they were a very good team, however, the White Sox had a very tightfisted owner. Charles Comiskey paid his ballplayers less than the players on other teams: For instance, the Reds’ leading hitter, Edd Roush, made $10,000, compared to Jackson’s $6,000, even though the Chicago right fielder’s batting average was consistently 30 to 40 points higher. Comiskey also skimped on meal money—giving his players a $3-per-day meal allotment when most clubs allowed $4—and on laundry bills. Some historians have even speculated that infrequent washing of the team’s uniforms led to the moniker Black Sox being attached to the club.

Fed up with the substandard pay, late in the summer of 1919, first baseman Chick Gandil devised a plan to make extra money from gamblers. As the White Sox would be a heavy favorite to win the World Series, Gandil realized the players could make a considerable amount of money if gamblers paid them to lose; he wanted gamblers to pay $10,000 per participating player. In order for Gandil’s plan to work, he needed the team’s two best starting pitchers, Cicotte and Williams, to go along with the scheme. He also needed to recruit Jackson, Chicago’s best hitter. Gandil also persuaded center fielder Happy Felsch and shortstop Swede Risberg to participate. One other player, a utility infielder named Fred McMullin, who was unlikely to even play in the series, was cut into the deal because he learned of the conspiracy and threatened to expose the plan if he was not included. An eighth player, third baseman Buck Weaver, was not among the players in on the scam, but he was a close friend to many of them and was in the room when the deal was being made.

Gandil made contact with gamblers while the White Sox were in New York to play the Yankees. A major New York gambler named Arnold Rothstein agreed to fund the fix, but he remained in the background to avoid being traced to the scandal. All communication and money was handled by small-time gamblers from New York, Boston, Philadelphia, and Texas. The gamblers gave the players $10,000 before the first game. The money went to Cicotte, who would pitch Game 1. Before the series even started, rumors circulated that the games were fixed. No one wanted to believe the gossip, especially Comiskey, and the gamblers involved were especially upset by the rumors, because the buzz lowered the odds.

The White Sox lost the first two games of the series, but rather than pass the rest of the money along to the team, the small-time gamblers used it to make their own bets on Cincinnati. As Cicotte was the only player to be paid, the other White Sox players in on the fix felt betrayed. Not surprisingly, Chicago won Game 3, angering the small-time gamblers who had bet on the Reds. Fearing he might have a rebellion on his hands, one of the gamblers behind the fix raised an additional $20,000 for the players, and when Cincinnati won the fourth game, the money was given to Gandil, who gave $5,000 a piece to Jackson, Risberg, Felsch, and Williams.

The 1919 Chicago White Stockings. The “Black Sox”—Top Row: Shoeless Joe Jackson (far left), Chick Gandil (second from left), Fred McMullin (third from left). Middle Row: Happy Felsch (third from left), Buck Weaver (far right). Bottom Row: Swede Risberg (second from left), Lefty Williams (second from right), Eddie Cicotte (far right). National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Cooperstown, N.Y.

Williams started—and lost—Game 5, putting the Reds one win away from the World Championship. With their backs to the wall, however, the White Sox won Games 6 and 7, pulling within one game of Cincinnati. Chicago manager Kid Gleason tapped Williams to start the eighth game. After the scandal broke, reports would circulate that gamblers, fearing a Chicago comeback, sent a thug to threaten Williams at his home the evening before Game 8. These reports, however, were apparently false. Nonetheless, Williams was ineffective, giving up four runs in just the first inning. Cincinnati won the game 10–5, and with it, the World Series.

Rumors swirled all winter long that the World Series had been fixed, and accusations continued during the 1920 season. In September, while the White Sox were locked in a pennant race with the Cleveland Indians, a grand jury convened to look into the allegations. On September 28, Cicotte admitted to the grand jury that he took money to lose the series. Jackson offered a similar confession. Baseball lore maintains that as Jackson was leaving the courthouse, a heartbroken young boy begged the right fielder, “Say it ain’t so, Joe,” to which Jackson replied, “I’m afraid it is, kid.” Although the exchange appeared in newspaper reports, the story is probably apocryphal, made up by a reporter for dramatic effect. The grand jury indicted the seven ballplayers involved, plus Buck Weaver, but when the case went to trial, their signed confessions—the only evidence against the Black Sox—turned up missing. Without the evidence, all eight players were acquitted of the charges.

The Black Sox Scandal generated tremendous fallout. Baseball had encountered allegations of fixed games in the past, but this was the World Series, the nation’s most prestigious sporting event. Major League Baseball’s reputation had been tainted. The scandal also ended the often rocky, nearly thirty-year-long friendship between Charles Comiskey and Ban Johnson who blamed each other for how the scandal was handled.

With the aftermath of the scandal threatening to destroy baseball, Albert Lasker, a co-owner of the Chicago Cubs, proposed the creation of a Commissioner of Baseball, a position that would be given sweeping powers over the leagues, to be held by someone who did not have a financial interest in any club. Lasker believed the public would view the commissioner as impartial; therefore, he believed, a commissioner could restore the public’s faith in the game. Ban Johnson opposed the idea because the establishment of a commissioner would take power from the American League president. Besides, Johnson would have preferred to see Comiskey take the fall for the scandal. Five American League clubs—Cleveland, Detroit, Philadelphia, St. Louis, and Washington—supported Johnson’s position. The National League, not wanting to see its reputation destroyed because of Johnson’s stubbornness, threatened to invite the Boston Red Sox, Chicago White Sox, and New York Yankees into its circuit, and to create its own commissioner for the expanded league. Faced with the possibility of abandonment by the National League, Johnson relented and accepted the establishment of a commissioner.

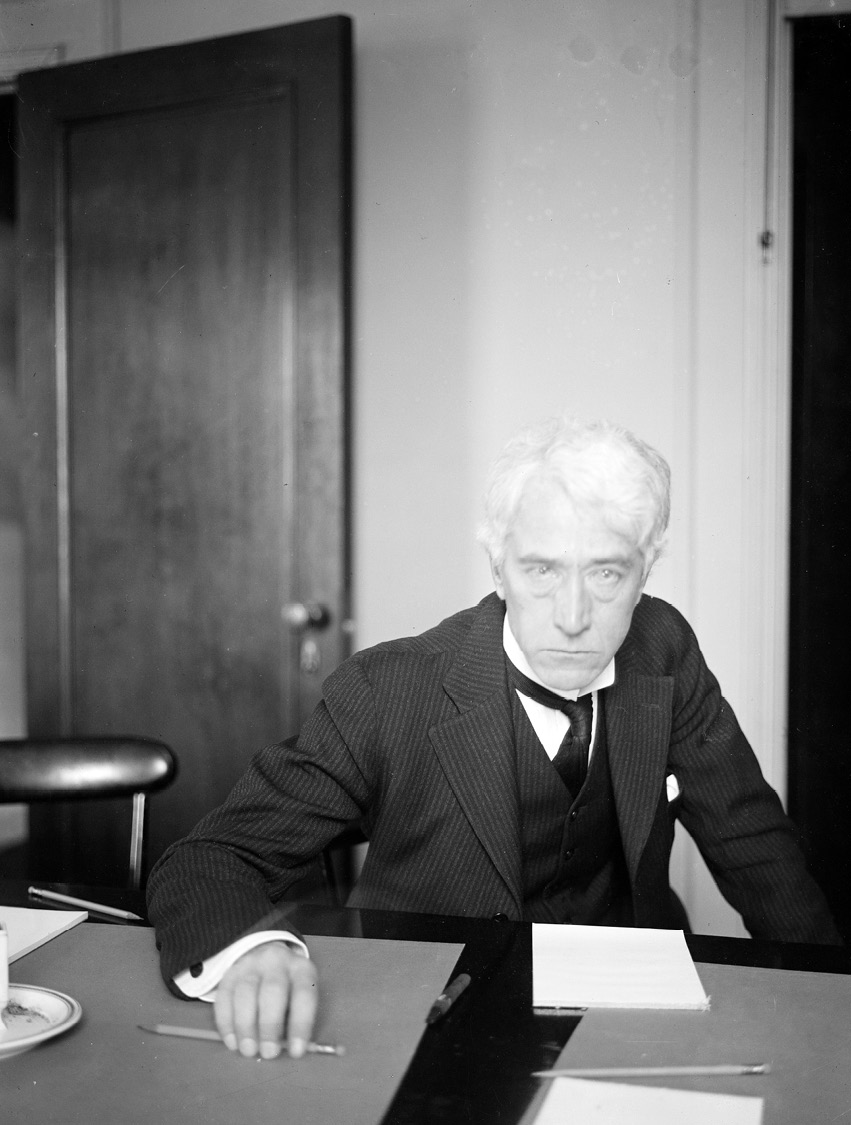

To fill the position, Major League Baseball selected federal judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis, who, not uncoincidentally, had earlier let the Federal League’s antitrust lawsuit linger on his docket until the league, drained of its resources, collapsed. Because club owners were desperate to restore the public’s confidence, they gave Landis unlimited power to act “in the best interest of baseball.” Baseball’s move was quickly copied by Hollywood. In the wake of the 1921–1922 Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle scandal, in which the silent film star was accused of raping and murdering starlet Virginia Rappe, the motion picture industry installed former postmaster general William H. Hays as the president of the newly created Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America and gave him broad powers to censor Hollywood’s films in order to improve the industry’s image.

Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis, the first Commissioner of Baseball. The Library of Congress Online Photo Archive

Landis, a tyrant at heart who ranked as one of the most arbitrary judges ever to sit on the federal bench, responded quickly to the Black Sox Scandal. Because the players implicated in the scandal were found not guilty, they all expected to return to baseball in 1921. Landis, however, issued lifetime bans on the seven players implicated in the scandal; he also banned Buck Weaver for not reporting the conspiracy. Landis extended his ban to any other baseball player who might play in a game with any of the Black Sox; thus, the banned players would never find a spot on a minor league team, a semipro team, or even an amateur team, as their presence in a game would immediately disqualify all the other participants from ever playing in Major League Baseball.

The Federal League and the First World War undermined baseball’s stability. As with other members of society, greed tempted ballplayers. In the post–World War I era, the same forces that touched off corruption in barrooms, Hollywood, and Washington, DC, caused baseball to sink into scandal. Kenesaw Mountain Landis was given enormous power to restore the public’s trust in his industry. His power grew further in 1922, when the antitrust lawsuit filed by the Baltimore Terrapins following the collapse of the Federal League finally reached the Supreme Court. In the case of Federal Baseball Club v. National League, the court, in a decision written by Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, ruled that baseball was not interstate commerce and was therefore not subject to the Sherman Antitrust Act. Essentially, the court held that baseball was a sport, not a business, a ruling that broadly expanded Landis’s power. Even today, Major League Baseball is the only sports league exempt from antitrust laws; the National Football League, National Basketball Association, and National Hockey League do not enjoy the same privilege. And, largely as a result of its harrowing experience in the Black Sox Scandal, baseball continues to fixate on gambling: In 1989 Major League Baseball imposed a lifetime ban on Pete Rose, the sport’s all-time hits leader, for gambling on the sport.