Chapter 5

The Art of Surveying the Sea

It is my duty to inform you of the excessive exertions made by Mr John Lort Stokes – Mate, and Assistant surveyor; and to request that you will represent his conduct to the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty, in the manner which you think proper. The greater part of the accompanying charts, and other documents, are his work, and I regret to say that his incessant occupation has brought upon a serious pectoral affection.

– Captain Robert FitzRoy, writing to Captain Francis Beaufort, from Monte Video, 30 November 1833

‘Officers Surveying’, watercolour by Captain Owen Stanley. Stanley portrays officers engaged in surveying from the land with various instruments. In the centre a man looks through a theodolite, and to the left a seaman crouches as he makes observations through a sextant on a fixed stand. The officer beside the tent is studying a dip circle, used for measuring magnetism.

Captain Robert FitzRoy had a dual role onboard HMS Beagle. In addition to commanding the ship he was also the senior surveyor. John Lort Stokes worked alongside him as his assistant and ship’s mate.

FitzRoy had received specialist training to create and supervise the production of the most accurate coastal profiles and views, maps and plans, for the compilation of printed Admiralty sea charts. Sea charts could be described as specific, and usually detailed, maps of the sea. The preparatory work for the charts took place on the large drafting table that dominated Darwin’s cabin. By his own admission Darwin had no drawing skills but he would have observed the work being undertaken. Unfortunately he did not write about the men’s drafting duties.

By the early 1800s large areas of South American waters remained uncharted. Substantial diplomatic benefits and trade opportunities could be gained by those countries who created, or acquired, the charts. Old Spanish charts existed for the purpose of supplying and maintaining her colonies, but few were freely available to other Europeans and the majority were inaccurate.

From the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 Britain started a concerted campaign to commission ships to investigate coastlines, inshore waters and rivers across the globe. Beagle was part of the strategy to establish an influential British presence in South America. Data was collected relating to the depth and nature of the sea or riverbeds. Sandbanks, shoals and reefs were identified and records made of currents, tides and winds. To collate this information soundings were taken, and observations were made with scientific instruments to obtain measurements afloat and from the shore.

‘Sounding Winch’, graphite drawing by Captain Owen Stanley. This winch was vital for establishing the depths of coastlines. This drawing, and the ‘Officers Surveying’, form part of an album of sketches compiled by Stanley during his command of the surveying ship, HMS Rattlesnake, 1846–9. Stanley was tasked to survey the inner route along the Great Barrier Reef and chart the southern coast of New Guinea.

Surveying parties often made coastal landings to take the various measurements and angles required for the survey. Captain Owen Stanley of the Rattlesnake created watercolours and drawings showing the survey parties at work using a variety of instruments. He also drew a picture of a type of newly invented deep-sea sounding winch that Beagle had onboard. This was used to take soundings to measure the depth of the ocean floor: from the small boats in shallower water the men would have used the traditional sounding or lead line. FitzRoy was laudatory of the benefits of the winch writing in the Narrative:

In again trying for soundings with three hundred fathoms of line, near the Island of St. Jago, we became fully convinced of the utility of a reel, which Captain Beaufort had advised me to procure. Two men were able to take in the deep sea line, by this machine, without interfering with any part of the deck, except the place near the stern, where the reel was firmly secured. Throughout our voyage this simple contrivance answered its object extremely well, and saved the crew a great deal of harassing work.

The surveyors would have been equipped with sighting telescopes and theodolites. Sextants were used to establish latitude, a ship’s distance north or south of the equator (0°), by astronomical observations. Longitude, a ship’s distance east or west on the Earth’s surface from a Prime Meridian (0°), was determined by chronometers. Thanks to FitzRoy, Beagle had an ample supply of these onboard, which enabled him to establish longitude by comparing the local time to the time at the Greenwich Meridian, used by British shipping as 0° Longitude for navigation and surveying. (Since the Washington Conference of 1884, Greenwich has been used internationally as the world’s Prime Meridian.)

To create accurate measurements the men used the established system of triangulation. The triangulation process required accurate knowledge of the distance between two of three points. Taking angular measurements from these enabled the third point to be precisely determined using theodolites or sextants. All of this data was vital to create an accurate chart.

FitzRoy noted the challenges of the survey work in his Appendix (No. 39, Notes on Surveying a Wild Coast) to the Narrative:

Our first object was to find a safe harbour in which to secure the ship. There we made observations of latitude, time and true bearing; on the tides and magnetism. We also made a plan of the harbour and its environs; and triangulations, including all the visible heights, and more remarkable features of the coast, so far as it could be clearly distinguished from the summits of the highest hills near the harbour. Upon these summits a good theodolite was used…

It was also essential for the seafarer to be able to recognize geographical locations. So in addition to the scientific data, the surveyors and other officers with artistic ability would create sketches, drawings and watercolours of ports, harbours and landfalls, headlands, hills and mountains, and any other readily identifiable topographical points of interests. Information relating to safe anchorage and the availability of water and wood was recorded. Collectively this information would feature on the charts to aid navigation.

In 1795 the British Admiralty established a specialist department, the Hydrographic Office, for the study of the surface waters of the earth and arrange the printing of the charts. Initially based in Whitehall, London, the Office is now in Taunton, Somerset, and is the world’s largest publisher of nautical charts; proudly boasting that it has been ‘charting the world for over 200 years’.

The first Admiralty Hydrographer was Alexander Dalrymple (1737–1808). He was appointed by order of George III in 1795. He set about reviewing the ‘difficulties and dangers to his Majesty’s fleet in the navigation of ships’. The work rate of producing charts was initially very slow and the first Admiralty chart of Quiberon Bay in Brittany was not published until 1800.

‘The Arctic Council’, oil painting by Stephen Pearce (1819–1904). The Arctic Council was not a formal organization, but the people were real. Seated in the centre is Captain Francis Beaufort. The ‘Council’ provided advice during the search for Sir John Franklin who disappeared searching for the North-West Passage. Some of the ‘Members’, including Frederick William Beechey, Sir James Clark Ross and Sir Edward Sabine, also had experience of sailing in southern waters.

Originally from Edinburgh, Dalrymple was an overly ambitious man with an argumentative temperament. He had gained seafaring and administrative experience in the East India Company, with whom he argued and fell out. However, some of his achievements were recognized as significant, and he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1765.

Dalrymple aggressively canvassed the Admiralty to be given charge of what in fact became Lieutenant James Cook’s first voyage to the Pacific in HM Bark Endeavour. Dalrymple was bitterly disappointed: the Admiralty were insistent that only a naval officer could take command of one of their ships. Dalrymple was adamant that the so-called Southern Continent existed and could be exploited for King and Country. His ardent beliefs featured in his An Account of the Discoveries Made in The South Pacifick Ocean, Previous to 1764, published in 1767. Since ancient times it was a widely held belief that there must be a large temperate land mass in the far south to balance the land masses in the north. Cook’s first and second voyages of discovery, ranging over the years 1768 to 1775, proved that no such land mass existed.

Cook took a copy of Dalrymple’s publication with him on his first voyage and found parts of it of great use, notably the inclusion of details of a sea-route between North Australia and New Guinea, a route discovered by the Spanish seaman Luiz Vaez de Torres in the early 1600s. Dalrymple came across Torres’ report of this voyage in Manila in 1769 and he was the first to name it the Torres Strait.

Dalrymple wrote another publication, An Historical Collection of the Several Voyages and Discoveries in the South Pacific Ocean (London, 1770), in which he continued to argue the case for the existence of a Southern Continent. Dalrymple’s cantankerous temperament was his undoing. On 28 May 1808 he was dismissed from the office of Hydrographer and in the following month he died, according to medical attendants, of ‘vexation’.

Captain Thomas Hannaford Hurd was appointed as the second Hydrographer from 1808 until his death in 1823. Born in 1747 in Plymouth he joined the navy on 1 September 1768 as an able seaman. He was of a more even temperament than his predecessor and a naval officer who had served with distinction under Admiral Lord Howe (1726–1799). He was selected for his past surveying experience (in 1789 the Admiralty had sent Hurd to make a detailed survey of Bermuda).

Hurd was given permission to sell charts to the mercantile marine and to the general public. In 1809 he was also given responsibility for the supply of timekeepers, and oversaw the production of volumes of sailing directions and the first chart catalogue.

Hurd was followed by Sir William Edward Parry (1790–1855), who was renowned as a polar explorer, although he was only in the position for six years from 1823 to 1829, covering Beagle’s first survey expedition.

Captain Francis Beaufort (1774–1857) was the fourth Hydrographer, and the one most closely associated with FitzRoy and the Beagle. He held the position for more than twenty-five years from 1829 to 1855, and was one of the most hardworking, sympathetic and supportive naval officers and administrators of his era. Originally from Navan in County Meath, Ireland, Beaufort’s father was the rector of Navan and a topographer and architect of note.

Beaufort became a gifted inventor: among his many accomplishments is the Beaufort Wind Scale, developed in 1805 to gauge wind strength. FitzRoy was tasked to test it out on the second voyage. He also introduced official Tide Tables in 1833 and in the following year Notices to Mariners, which were published updates of what the Hydrographic Office now calls ‘safety-critical navigational information’, that were used in conjunction with older charts until they were updated. By 1855, the year of Beaufort’s retirement, the Hydrographic Office’s chart catalogue listed 1,981 charts, with 64,000 copies issued to the Fleet.

Thanks to the hard work and vision of Beaufort the Admiralty became the foremost authority in the world in the techniques of hydrography and cartography. He had personal first-hand experience of undertaking survey work in South American waters. He supervised surveys of the Mediterranean, the African coast, the Pacific Ocean, South America, Australia, New Zealand and China, and various polar voyages. Among the long list of eminent naval men trained and guided by Beaufort are the names of Frederick William Beechey, Edward Belcher, Henry Foster, Phillip Parker King, Henry Charles Otter, William George Skyring, William Henry Smyth, Owen Stanley, Alexander Vidal, and Robert FitzRoy. Beaufort became an admiral and was knighted for his naval and hydrographic services.

FitzRoy and Beaufort maintained a fairly regular and revealing official and private correspondence until the latter’s death in 1857. In fact FitzRoy’s Admiralty Instructions categorically stated he ‘should keep up a detailed correspondence by every opportunity with the Hydrographer’.

In part, Beaufort was also responsible for the inclusion of someone who later became the most celebrated member of Beagle’s crew. It was through his contacts that Darwin was introduced to FitzRoy. Jordan Goodman, author of The Rattlesnake – a Voyage of Discovery to the Coral Sea, one of the expeditions commanded by Owen Stanley, aptly summarizes Beaufort’s objectives and the importance of carrying naturalists aboard survey ships:

He thought of surveying in a broad sense of scientific investigation and knowledge. To him, hydrography, was not just a matter of knowing coastlines…and so forth…but also included natural history, both of land and sea, geography and ethnography. To this end, he wanted survey ships to carry naturalists to make the necessary observations and collections to further that branch of knowledge and to fill the metropolitan, provincial and private museums with the exotic specimens of flora and fauna they encountered. He wanted discovery and explorations to be at the centre of marine surveys.

Beaufort and FitzRoy shared many common interests and personal battles with the Admiralty. The Hydrographer was a founder Member of the Royal Geographical Society in 1830. Seven years later, as a result of his successful survey work on the Beagle, FitzRoy was awarded the Society’s Gold Medal. Whenever possible Beaufort tried his best to help his colleague, although he was not always able to persuade the Admiralty in his favour.

On 26 March 1833 FitzRoy purchased the schooner Unicorn in the Falkland Islands, because he was certain that he could speed up the survey work if he acquired an additional vessel. She had been built as a private yacht and later armed and used by Lord Thomas Cochrane, the inspiration for several fictional heroes including Patrick O’Brian’s Captain Jack Aubrey. It was love at first sight, Fitztroy wrote: ‘A fitter vessel I could hardly have met with, one hundred and seventy tons burthen, oak built and copper fastened throughout, very roomy, a good sailer, extremely handy, and a first-rate sea-boat’.

FitzRoy used $6,000 (nearly £1,300) of his own money, as he did not have Admiralty approval to hire or purchase additional vessels, and paid considerably more to fit her out. She was re-named Adventure, the name of the main escort ship on Beagle’s first voyage, and according to Darwin, in deference to the ship that sailed with Captain Cook’s Resolution on his second voyage of discovery. FitzRoy wrote to Beaufort in a confident, optimistic tone: ‘I believe that their Lordships will approve of what I have done…but if I am wrong, no inconvenience will result to the public service, since I alone am responsible for the agreement…and am able and willing to pay the stipulated sum’. FitzRoy had also written directly to the Admiralty. The secretary at the Admiralty had underlined the words ‘am able and willing’ and wanted Beaufort’s opinion on the matter. Beaufort placed on record:

There is no expression in the Sailing Orders, or surveying instructions, given to Commander FitzRoy which convey to him any authority for hiring and employing any vessels whatever. On the other hand, there can be no doubt that by the aid of small craft he will be sooner and better able to accomplish the great length of coast which he has to examine – and which seems to contain so many unknown and valuable harbours; – especially if he finds it necessary to trace the course of a great river, which had been reported to him as being navigable almost to the other side of America. It may also be stated to their Lordships that the Beagle is the only surveying ship to which a smaller vessel or Tender has not been attached.

Despite Beaufort supporting his case, the Admiralty’s response was negative. FitzRoy argued his case in further correspondence, but he was ordered to sell the Adventure on 22 July 1834: the Admiralty was adamant that he should focus his command solely on the Beagle. The sale was, in his own words, ‘very ill-managed, partly owing to my being dispirited and careless’. He sold the vessel for just £1,400: the extra costs of fitting her out meant that he made a significant loss in the enterprise. Early in the voyage, in October 1833, FitzRoy had hired two considerably smaller vessels, the Paz (15 tons) and the Liebre (9 tons) to assist the survey work. They were relinquished in August 1834. FitzRoy personally paid the hire cost of £1,680. Stokes recalled that, ‘These craft did one or other of the officers survey the coast from the Rio Plata to the Straights of Magellan over a period of nearly twelve months, whilst the Beagle was engaged further south’.

FitzRoy had transformed the small boats:

No person who had only seen the Paz and Liebre in their former wretched condition, would easily have recognised them after being refitted, and having indeed almost new equipment. Spars altered, and improved rigging, well-cut sails, fresh paint, and thorough cleanliness, had transformed the dirty sealing craft into smart little cock-boats: and as they sailed out of Port Belgrano with the Beagle, their appearance and behaviour were by no means discouraging.

Perhaps because the survey work was routine rather than something extraordinary there are remarkably few expansive and detailed descriptions. FitzRoy wrote one of the most in-depth to Beaufort from Maldonado, 7 June 1833: ‘I cannot omit an opportunity of telling you how we are going on, though I have no “Documents” ready for you yet’. He continued:

In those cockleshells [the Paz and Liebre, called ‘cockleshells’ because they were small vessels] – the Coast between Port Desire and Bahia Blanca has been explored satisfactorily, and when you see the New Charts, you will say ‘I had no Idea there remained so much to be done on that Coast.’ Their work has been confined to the immediate vicinity of the land; there is still work for the Beagle near tide races and outlying shoals. They have found a new River called by the Indians ‘Chubat’ in Lat. 43 degrees 20’ S. Long. 65 degrees 15’ W., which though not large nor deep, is rapid & flows through a most fertile country with so winding a course that a succession of Islands, or ‘water meadows’, might be formed by canals, thus which would be at the same time fortified against the Indians who never cross water in their attacks upon civilized man. Lt. Wickham says the river is about 100 yards wide, and will admit vessels of thirty tons burthen.

FitzRoy reaffirmed the use to Beaufort of the Paz and Liebre:

The Labyrinth between San Blas & Bahia Blanca is partly finished. Mr Stokes is now working at that part. Off the ‘Islas de la Confusion’, the aforesaid Labyrinth, there are shoals, out of sight of land, & extremely dangerous. In the Beagle, although so small, we could not have overhauled these places well, nor half so quickly, as the cockleshells. They are but decked boats…but their work will speak for them.

‘Bivouac at the head of Port Desire inlet’, after Conrad Martens, engraved as an illustration for the Narrative (1839). This plate also includes three other views of Port Desire. Richard Darwin Keynes describes his great-grandfather’s explorations there at Christmas-time 1833. He ‘took a long walk to the north, where he found a veritable desert composed of gravel, with rather little vegetation and not a drop of water. The dryness of the country was nevertheless redeemed by the fact that it supported many guanacos’. The uppermost illustration reveals that there were plenty of rabbits.

In Life and Letters Bartholomew James Sulivan has left behind some of the most insightful observations of the survey work in the Paz and Liebre, including descriptions of their interiors, and the activities of ship’s boats:

The cabin in Stokes’ craft [Liebre] is seven feet long, seven wide, and thirty inches high. In this three of them stow their hammocks, which in the daytime form seats and serve for a table. In a little space forward, not so large, are stowed five men. The larger boat carries the instruments. Her cabin is the same size, but is four feet high, and has a table and seats.

In December 1834 Sulivan participated in a separate survey in one of Beagle’s boats of the east side of the island of Chiloe and islets in the Gulf of Ancud, a large body of water separating Chiloe Island from the mainland of Chile. He was assisted by Darwin, three officers and ten men. He revealed some of the lighter moments amidst the essential but mundane task of surveying by day and night: ‘We are all then crowded into one tent and went on singing till twelve, and I have never under any circumstances saw a more merry party. All the comic songs that any one knew were mixed up yarns of English, Scotch and Welsh’.

South West Opening of Cockburn Channel (Mount Skyring), engraving, after W. W. Wilson from the Narrative (1839). Although only the name Wilson is inscribed below this plate (he served on HMS Adventure during Beagle’s first expedition) other officers and artists, including Martens, almost certainly contributed to this multi-view sheet.

FitzRoy thought very highly of Sulivan. He was successful in recommending him for a later survey voyage. Writing after the end of his Beagle command from his land-based address at 31 Chester Street, FitzRoy gives a carefully balanced account of the strengths and weaknesses of his former officer but concludes that he ‘is up to the business completely. He is as thorough a seaman, for his age, as I know…. He is an excellent observer, calculator, and surveyor’. However, FitzRoy did note that, ‘He is not a neat draftsman, though his chart work is extremely correct. (His hand is not quick enough for his mind, or his mind is too quick for his hand)’.

The official Admiralty Instructions, compiled largely by Beaufort, offered guidance on how Beagle’s surveyors should approach the task of compiling coastal profiles. Officers were not to waste time creating artworks. There was an acknowledgment of the significant workload of each officer:

In such multiplied employments as must fall to the share of each officer, there will be no time to waste on elaborate drawings. Plain, distinct roughs, every where accompanied by explanatory notes and on a sufficiently large scale to show the minutiae of whatever knowledge has been required, will be documents of far greater value in this office, to be reduced or referred to, than highly finished plans, where accuracy is often sacrificed to beauty.

The Admiralty was clearly of the opinion that too much time was wasted on drawing hills: …which in general cost so much labour, and are so often put in from fancy or from memory after the lapse of months, if not years, instead of being projected while fresh in the mind, or while any inconsistencies or errors may be rectified on the spot. A few strokes of the pen will denote the extent and direction of the several slopes much more than the brush, and if not worked up to make a picture, will really cost as little or less time. The in-shore sides of hills, which cannot be seen from any of the stations, must always be mere guesswork, and should not be shown at all.

‘Southern Portion of South America’, map from the Narrative (1839) engraved by J. Dower, Pentonville, London. Dower was a London-based draughtsman, engraver and publisher.

Beagle’s surveyors had to provide the perpendicular height of all remarkable hills and headlands and,

All charts and plans should be accompanied by views of the land; those which are to be attached to the former should be taken at such a distance as will enable a stranger to recognize the land, or to steer for a certain point; and those best suited for the plan of a port should show the marks for avoiding dangers, for taking a leading course, or choosing an advantageous berth. In all cases the angular distances and the angular altitudes of the principal objects should be inserted in all degrees and minutes on each of the views, by which they can be projected by scale so as to correct any want of precision in the eye of the draftsman. Such views cannot be too numerous; they cost but a few moments, and are extremely satisfactory to all navigators.

The Admiralty was not paying FitzRoy’s team to paint pretty pictures. They wanted the official surveyors to produce images to improve navigation. To this end the creation of coastal profiles and views was a vital part of the production process to create accurate Admiralty charts.

The importance of creating views of the coastlines from the sea had been highlighted since the Admiralty Instructions of 1759. They contained a long list of things that were considered important to observe and record. These observations were to include: sands, shoals, sea marks, soundings, bays and harbours, times of high water and setting of tides, and, in particular, information such as the best anchoring and watering places, and descriptions of the best methods of obtaining water, fuel, refreshment and provisions. Fortifications were also to be described and their form, strength and position noted. The Instructions specifically indicated that if a ship carried any capable artists they should provide illustrations, with references and explanations attached, of this information. The material should then be submitted to the Admiralty in London.

Naming newly encountered places was a challenge for all explorers and surveyors. Beagle’s Admiralty Instructions (drawn up by Beaufort) offered advice and guidance on how to proceed:

Trifling as it may appear, the love of giving a multiplicity of new and unmeaning names tends to confuse our geographical knowledge. The name stamped upon a place by the first discoverer should be held sacred by the common consent of all nations; and in new discoveries it would be far more beneficial to make the name convey some idea of the nature of the place; or if it be inhabited, to adopt the native appellation, than to exhaust the catalogue of public characters or private friends at home. The officers, and crews, indeed, have some claim on such distinction.

Indeed, the Instructions went so far as to encourage the use of names of officers and crew, ‘which slight as it is, helps to excite an interest in the voyage’.

Completed charts, plans, views, drawings and watercolours, as well as letters and Darwin’s specimens, were sent back to England at every available opportunity that Beagle came into contact with a British naval or merchant ship on route home. Writing to Beaufort in a private letter from Valparaiso on 14 August 1834, FitzRoy confides:

A merchantman going to Liverpool tempts me to send you a short letter…as there is much material I doubt it will be ready for the Samarang [HMS Samarang]. I shall try hard. The Falkland survey is better than I had reason to expect – all the exterior is well laid down. There is much to do about the eastern entrance of the Straits of Magellan – extensive banks and very difficult tides. I do not think the present copper plates of Magellan’s Strait will allow of the new work being combined with the old – a new edition will perhaps be required. The title of the present charts stands in the way of an extensive and well sheltered port on the east coast of Tierra del Fuego.

Robert FitzRoy’s letter to Captain Francis Beaufort from Valparaiso, 2 November 1834, informing the Hydrographer that the list of charts, views and directions is inside the tin case that contains the charts.

FitzRoy wrote again to Beaufort from Valparaiso on 2 November 1834: ‘Sir, Herewith I have the honor of forwarding to you the Charts – Views – and Directions – mentioned in the enclosed list’. And, ‘Note. The list is inside the tin case which contains the charts’. Included in this consignment were twenty-three charts including the east and west coast of the Falklands, Strait of Magellan and Beagle Channel, and ninety-five views including the interior of Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego. Also ten plans including Middle Cove, part of the north side of Wollaston Island and part of Hardy Peninsular, Port William and Port Desire.

During the voyage FitzRoy was also receiving consignments of reference material from Beaufort. Two years previously on 16 August 1832 FitzRoy wrote to him requesting he be,

…furnished with the following Charts and Papers, as they will expedite the work very materially.

Charts

River Plate, two sheets, two Copies

Captain King’s Charts of these Coasts (when published), six Copies

South Sea, in three sheets, two Copies

Tracing Paper…two squires

The two copies of the River Plate, two copies of Captain King’s Charts, and two of the South Sea, are for working upon, for laying down every addition which is in our power to make, and sending them to England at different times without depriving ourselves of the only copy on board. The tracing paper is extremely useful. Having a large glass tracing frame, no opportunity of tracing Charts or Plans, printed or manuscript, which I can borrow or buy, and which promise to be of any use, is omitted; and I did not bring enough from England. The other four Copies of Captain King’s Charts are requested by me for the sole purpose of giving them away from time to time to the Local Authorities who may render us assistance in our progress, and who did materially assist the Adventure and the Beagle in their former voyage. May I beg also that the Charts and Paper may be packed in tin and rolled instead of doubled.

If FitzRoy believed that he might have a discrepancy in his chart work measurements or observations, he would retrace his steps until he ascertained the true results. He proved that the French admiral and explorer Baron Albin Rene Roussin (1781–1854) had made errors in his charts created during his 1819 exploration of the coasts of Brazil and the Abrolhos Islands. He wrote to inform Roussin of his findings but received no reply.

An open folio containing coastal profiles and views can be seen in an oil painting created by Augustus Earle, FitzRoy’s first artist. Earle’s picture portrays the interior of a midshipmen’s berth at sea and the folio is clearly visible on the deck. Some naval instructors are teaching various disciplines: as part of their on-going naval training midshipmen (trainee officers) were taught by their superiors to draw and use watercolour. The painting also portrays navigational instruments including sextants and a telescope.

‘Life on the ocean…’, oil painting by Augustus Earle. The deliberate close-cropping of Earle’s compositions and visually striking juxtaposition of objects with people allies the artist to the genre of caricature. Note the curious view of legs on the steps (upper left) and the marine’s head and upper shoulders emerging from the hatchway. But Earle also succeeds in capturing the camaraderie and cooperative activities of life afloat.

‘Divine Service…’, oil painting by Augustus Earle, almost certainly the companion picture of the painting opposite, exhibited at the Royal Academy of Arts in 1837. If this does portray Admiral Searle, his appearance certainly differs from his description in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, which describes him as being a ‘handsome, strongly built man of middle height, with black hair and dark complexion’.

In Earle’s quirky composition he plays around with conventional scale and perspective. He exaggerates the height between the decks. It is likely that this was the painting exhibited at the Royal Academy of Arts in 1837 under the title ‘Life on the ocean, representing the usual occupation in the steerage of the young officers of a British frigate at sea’.

Earle’s painting was produced in the penultimate year of his life with a companion picture entitled ‘Divine Service as it is Usually Performed on Board a British Frigate at Sea’ (also exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1837). It has been suggested by some writers (including Dr Janet Browne) that this picture portrays Darwin, FitzRoy (as the captain reading the Bible) and Fuegia Basket. This is wishful thinking. The pair of pictures certainly derive from Earle’s first-hand seafaring experiences, and more specifically relate to his time aboard HMS Hyperion. Earle’s oil paintings are now at the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, and the related preparatory watercolours are part of the Rex Nan Kivell Collection, National Library of Australia in Canberra. The watercolours contain considerably less detail, although the height of the ship’s decks is more authentic than the vast spaces portrayed in the final oil paintings. One of the watercolours has a title (originating from Earle) that indicates the date ‘1820’ and the name of the ship Hyperion inscribed on the mount: ‘130 Divine Service on board a British Frigate, H.M.S. Hyperion 1820’. Assuming that Earle’s pictures feature accurate portraits rather than tableaux, the captain of this ship at that time would have been Admiral Thomas Searle (1777–1849). Earle sailed on this ship shortly after the start of the blockade by Lord Thomas Cochrane, of Callao, the largest and most prominent port in Peru, in November 1820, during the second phase of Chile’s War of Independence 1818–26, during which Cochrane was First Admiral of the Chilean Navy. Earle returned to Rio de Janeiro on the frigate Hyperion arriving on 10 December 1820, where he remained for the next three years.

Topographical drawing to aid navigation was encouraged in specialist schools towards the end of the seventeenth century. In 1673 Christ’s Hospital received its second Royal Charter (Edward VI conferred the first one in 1553) to create the Royal Mathematical School whose original purpose was to train mathematicians and navigators for the navy and mercantile service.

Thomas Phillips (d. 1693), the military engineer and draughtsman, is arguably the earliest recorded British draughtsman to have produced coastal profiles. He worked for Charles II and produced designs of sea-battles and depictions of maritime fortifications that also incorporated coastal profiles and landscape views. In ‘A Prospect of St. Peters Port and Castle Cornett in the Island of Guernsey, 1680’ he demonstrates considerable drawing skill, and a profound knowledge of seafaring, as the shipping and craft are portrayed in convincing detail.

The eighteenth century ushered in a new systemized and regulated surveying regime. Naval officers and seamen started to produce coastal profiles and views on a regular basis in significant numbers, and some of remarkable merit. Among them Peircy Brett (1709–1781) stands out as one of the most accomplished exponents. He was also one of the earliest to effectively combine his images with descriptive text relating to his visual observations of headlands, profiles and views, and details required for safe sailing and landing.

At the outbreak of war with Spain and France in 1740 Brett accompanied Commodore George Anson (1697–1762), and became his second lieutenant, on a voyage to the Pacific with instructions to attack Spanish possessions and ships. Anson commanded the Centurion and by their return in 1744 they had circumnavigated the world. Among Brett’s pictorial work produced on this extraordinary voyage ‘A View of Streight Maire between Terra del Fuego, and Staten Island’, produced in the early 1740s, is one of several examples revealing his attention to detail that would have been of significant use to the seafarer. This profile relates to a part of the world where Beagle would spend a large part of her time undertaking survey work.

Brett’s pictures were produced for a very practical purpose and they often included extensive notes relating to location, depths, currents and wind direction, as well as other points of interest. Some of Brett’s drawings were created specifically to be engraved for the official published account of the voyage. As part of his naval training FitzRoy would have been familiar with Brett’s work.

Naval schools and colleges were established during the eighteenth century. Part of their curriculum was dedicated to teaching the cadets and trainee officers how to draw. They offered art tuition and art competitions to raise the standard of drawing for surveying.

In 1715 the Royal Hospital School was established at Greenwich to educate the sons of seamen. They were,

…instructed in Writing, Arithmetic and Navigations by a School Master appointed for that purpose; who also instructs those in Drawing who shew genius for it…. All the Boys attend the Directors, once a year to be viewed, when they bring specimens of their several performances; and three of them who produce the best Drawings after nature, done by themselves, are allowed the following premiums [prizes], according to their respective merit: First prize a Hadley’s quadrant, Second prize – a case of mathematical instruments and for the Third prize a copy of Robertson’s Treatise on Navigation.

During the early decades of the nineteenth century professional maritime artists were appointed to teach naval cadets in order to raise the standard of their work. John Thomas Serres (1759–1825) taught drawing at the Chelsea Naval School. His Liber Nauticus, and Instructor in the Art of Marine Drawings was published by Edward Orme of Bond Street, in two parts in 1805 and 1806. This was a collaborative work produced with his father, Dominic Serres (1722–1793), and was intended to aid the student of marine art (including trainee and commissioned naval officers) in acquiring the technical competence to produce authentic marine pictures.

Dominic Serres was a French emigré, born in Gascony, who settled in England. He was the only marine painter to be a founder member of the Royal Academy of Arts in London. He was well respected; in fact, so much so that he was appointed marine painter to George III. John Thomas was trained by his father and his first teaching post was at the short-lived Maritime School in Paradise Row in Chelsea, 1779–87. On the death of his father he succeeded him as marine painter to the King and also to the Duke of Clarence, the future William IV. He was also appointed as the official draughtsman to the Admiralty and in this capacity he was often away, for up to six months at a time, engaged in survey work afloat. He produced ‘drawings in the form of elevations [profiles]’ of the headlands and landfall of the coasts of France and Spain. Some of these were published in The Little Sea Torch in 1801, which contained text translated from a French sailing guide.

FitzRoy himself benefited from the tuition of a professional marine painter. In February 1818, aged 12, FitzRoy entered the Royal Naval College at Portsmouth where he excelled. As part of his naval training he received instruction from the accomplished maritime artist John Christian Schetky (1778–1874), who had been appointed as Professor of Drawing in 1811, a position he held for twenty-five years until the closure of the college in 1836.

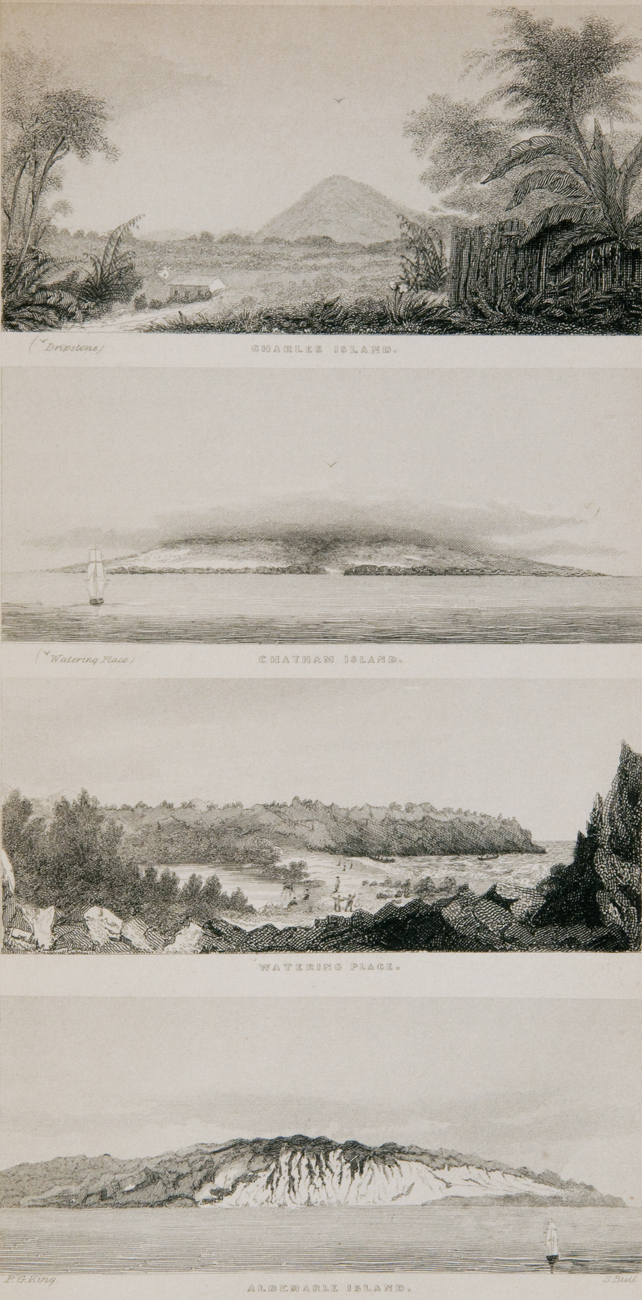

Charles Island, Galapagos by Philip Gidley King. This loosely constructed preparatory wash drawing captured the essence of the place. Under FitzRoy’s editorial eye the outline and composition have been tightened up for inclusion as an engraved illustration in the Narrative (1839).

Schetky’s daughter, Miss S. F. Ludomilla Schetky, wrote a lively biography of her father entitled Ninety years of Work and Play: Sketches from the Public and Private Career of John Christian Schetky (1877). The book reveals that he was born in Edinburgh. From an early age he had a passion to join the Royal Navy, and he served as a midshipman for two years in HMS Hind (the same ship FitzRoy later sailed on). However, his naval service was cut short because his parents disapproved of his career choice, and so he ‘consoled himself by painting the great swan-like vessels in which he longed to sail’. He was taught to draw by the Scottish landscape painter Alexander Nasmyth (1758–1840).

From the age of 14, Schetky assisted his mother in teaching drawing and painting to a class of ladies. In 1808 he taught drawing at the Military College of Sandhurst, based at Great Marlow, but after three years he applied for the position at Portsmouth ‘having all my life cherished an affectionate regard for the navy’.

Schekty was a popular professor with his naval students, many of whom went on to become captains and admirals, and was also well regarded in the mainstream art community. He was known for his carefully crafted marine subjects, especially large-scale sea-battles. The artist had a preference for using sepia, and many of his paintings have a predominant coppery-brown hue. He exhibited at the short-lived Associated Artists in Water-Colours; also at the Society of Painters in Water-Colours; and became a regular exhibiter at the Royal Academy of Arts in London.

Charles Island, Galapagos, engraving after Philip Gidley King from the Narrative (1839). The islands of Chatham and Albemarle are also featured on the same plate.

He provided sketches of naval ships for J. M. W. Turner’s vast oil painting of the Battle of Trafalgar, 21 October 1805. Turner (1775–1851) wrote to him asking,

If you will make me a sketch of the Victory…three-quarter bow on starboard side, or opposite the bow port, you will much oblige; and if you have a sketch of the Neptune, Captain Fremantle’s ship, or know any particulars of Santissima Trinidada, or Redoutable, any communication I will thank you much for.

Turner had been commissioned by George IV to paint the picture in 1822 to hang in St James’s Palace. It took about eighteen months to complete. However, even with Schetky’s assistance to ensure technical accuracy and detail, the picture failed to impress the King and the nautical fraternity, who wanted a more literal rather than high-Romantic interpretation of the battle. Vice-Admiral Sir Thomas Masterman Hardy, who commanded HMS Victory during the battle, thought the ship resembled a row of houses rather than a ship-of-the-line, as Turner had positioned her too high out of the water. The Duke of Clarence, the future ‘Sailor King’, took Turner to task and told him: ‘I have been at sea the greater part of my life, Sir, you don’t know whom you’re talking to, and I’ll be damned if you know what you are talking about’.

As Professor of Drawing at the Royal Naval College in Portsmouth Schetky maintained good relations with the Hydrographic Office and counted Admiral A. B. Becher, a former pupil and Assistant Hydrographer to the Admiralty during the tenures of Parry, Beaufort and John Washington, as a friend. Alexander Bridport Becher was born in 1796 and packed a great deal into his eighty years of life. He entered the Royal Naval College in April 1810. He spent most of his career at the Hydrographic Office but in his early years he participated in the surveying of the Canadian lakes, parts of the African coast, the Cape de Verde Islands, the whole of the Azores and the Orkneys.

During his time as Assistant Hydrographer he also issued the first edition of the Nautical Magazine, and was active in a management and editorial capacity for thirty-nine years. In its early years it was subsidized by naval and mercantile funds to about £100 per annum. The magazine was a vital reference work and included a wide range of data and observations to assist navigation. FitzRoy ordered the latest copy of it during his command of Beagle.

Becher recalled the influence of Schetky:

He brought us a new state of things altogether. We were never allowed outside the dockyard gates before he came: but he looked up the college boat directly, and got permission to take us out sketching – and such jolly expeditions as we used to have all along the coast there!

He described his teacher as, ‘A fine tall fellow he was, with all the manners and appearance of a sailor – always dressed in navy-blue, and carried his call [bosun’s whistle], and used to pipe us to weigh anchor, and so on, like any boatswain in the service’.

Schetky was generous in his artistic advice. In 1831 he wrote to another former pupil, Captain George White, who at that time was stationed in HMS Melville off the coast of Portugal. He advised:

No doubt you are sketching every day. Now let me advise you to make minute studies of every kind of boat of the country, and draw the inside of them as well as sheer and shape – ay, the inside, with all the gear you see in them – nets, crab-pots, spars, casks, sails, and everything, most carefully, marking the colours of each, and depend upon it will find the good of it hereafter. What would not I give just now for a minute study of a Lisbon bean-code for my present picture! but I have it not and therefore I am asking everybody about their style and character.

The naval art instructor also advised: ‘Draw also, and colour, the pescatori and all sorts of boatmen, and always write under each sketch where they belong to, and above all, date them: it is mighty pleasant hereafter to know where you were on such a day – it is a sort of graphic log’.

Unfortunately there are no records revealing an on-going relationship between FitzRoy and Schetky. However, as an impressionable boy it is unlikely that FitzRoy would forget his mildly eccentric and enthusiastic teacher, and he certainly appears to have benefited from his art tuition.

FitzRoy’s art training under Schetky may well have encouraged him to think beyond the creation of pictorial works for a practical purpose. Although in the eighteenth century Sir Joseph Banks had encouraged the inclusion of artists and draughtsmen onboard naval ships, it was not standard practice. Anyone onboard with a degree of artistic talent was engaged when necessary. But FitzRoy wanted the best results and this led him to personally pay for the artists who accompanied him on the Beagle voyage. They were his ‘painting men’. But he was well aware of his Admiralty Instructions and the priority that dictated that craft should be placed before art.

Although many hundreds of drawings and watercolours showing coastal profiles and views, landfalls, rocks, mountains and landmarks of note, were produced throughout the course of Beagle’s survey work, only a small number have survived. Despite the strictures of the Admiralty Instructions, some of them do have artistic merit. They were not originally intended for display or storage in archives and museums, but for most of them that has become their fate today.

Less than thirty original coastal profiles have survived by Conrad Martens that relate to the Beagle voyage, and significantly less can be attributed to Augustus Earle. Part of their brief was to assist with the survey work, although both men left the voyage before it was completed. Although FitzRoy personally paid for his shipboard artists, as a formality they were approved by the Admiralty (with Beaufort’s help) for the expedition; also accommodated and fed at public expense. Almost all of the pictorial work they created was deemed to be FitzRoy’s personal property, while the material created by his officers that directly related to the survey and chart work was the property of the Admiralty.

Admiralty chart of the Galapagos Islands (dated 1836), surveyed by Captain FitzRoy and the officers of HMS Beagle, bearing the stamp of the Hydrographic Office. Detailed surveys relating to specific island areas are arranged around the edges of the main chart. Depictions of coastal profiles, headlands and landfalls were arranged in such a manner on charts to aid navigation.

FitzRoy was very impressed with John Lort Stokes’s skill, commitment, and rapid work rate in producing the immensely valuable coastal profiles and views, although none of his work appears in the official Narrative. Beagle’s captain also thought highly of the work of John Clements Wickham and Philip Gidley King. He selected a series of four landscape views by King, including the islands of Charles, Chatham and Albemarle in the Galapagos, for the Narrative. King’s view of a location where they obtained fresh water, simply named Watering Place, was also featured.

So much time, effort and expense was dedicated to producing the original profiles, views, plans and drawings for the naval charts. The costs of funding the Hydrographic Office and the survey voyages (exclusive of the Arctic and Antarctic expeditions) in 1837–8, which was placed before Parliament, revealed the sum of £68,517 – millions of pounds in todays money.

Not everyone appreciated the original works. During the mid-Victorian period the curator of the Hydrographic Office disposed of a large number of the original views. These works were a means to an end; however FitzRoy, who had laboured for so long to create (and supervise the production of) a significant number of them, would surely have disapproved.

Photography gradually took over from the role of the ship’s artists and draughtsmen. The earliest photographic views were received by the Hydrographic Office in 1854, and by the early 1900s photographic records were commonplace. Even so, naval surveyors were still in service until halfway through the twentieth century.

After FitzRoy’s death Admiral Sir George Henry Richards (1820–1896), Hydrographer to the Admiralty, summed up FitzRoy’s contribution to naval survey work:

No naval officer ever did more for the practical benefit of navigation and commerce than he did… The Strait of Magellan, until then almost a sealed book, has since, mainly through his exertions, become a great highway for the commerce of the world – the path of countless ships of all nations; and the practical result to navigation of these severe and trying labours, which told deeply on the mental as well as the physical constitution of more than one engaged, is shown in the publication to the world of nearly a hundred charts bearing the names of FitzRoy and his officers, as well as the most admirably compiled directions for the guidance of the seamen which perhaps was ever written, and which has passed through five editions…