Alger was born in 1904, and the Hiss family was society in Baltimore, Maryland. They had a horse and carriage. There were cooks, chauffeurs, chambermaids as well as nannies and private schools for the children. But when he was two and a half years old, something went badly wrong; the only hope for the family finances was a cotton mill down south in Charlotte, North Carolina. Alger’s mother flatly refused to go. The Sunday morning after she had said so, Alger’s father shouted downstairs that she was to call the doctor.

Then he slit his throat from ear to ear with one of those old-fashioned straight-edge razors.

The horse and carriage had to go. No electricity in the house, no heat except for the kitchen stove – the kids fetching coal for it from the basement. But they kept a servant. The Hisses just might have been connected to the princely family of Hesse-Darmstadt; a tight budget can’t take away the sense of entitlement that comes with a name like that, and such people have servants. Mrs Hiss went right on preparing her children for their place in Baltimore society. After school every weekday, Aunt Lila read out loud: Coleridge, Scott, Dickens, Shakespeare, the King James Bible, some light stuff too, Edward Lear’s limericks and Alice’s Adventures. There was tennis and horse riding. Saturdays were for music lessons, art classes, German conversation. Sundays were for Sunday School and church; this was a religious family – grace and family prayers too – an Episcopalian family, the faith of the American elite.

There were five Hiss children, a happy, chattery, close-knit clan despite the family tragedy. Alger was the playful, mischievous one, just like a hero in one of those old-fashioned books for boys. He scared his younger brother Donald with bears under the bed and made him giggle in church by pretending to stick hatpins in ladies’ rumps. He was lazy at school and lousy at lessons, skiving off to lie in the sun, practice smoking, play pool. His only distinction was an athletics medal won only because he was so short – they called him “runt” – that the coach could pit him against younger kids.

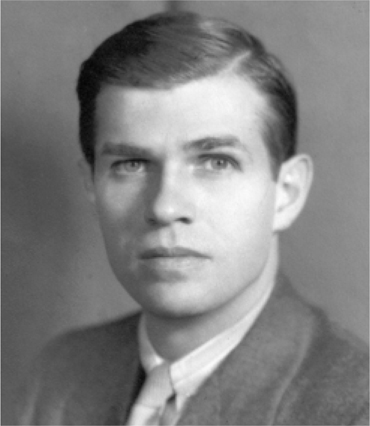

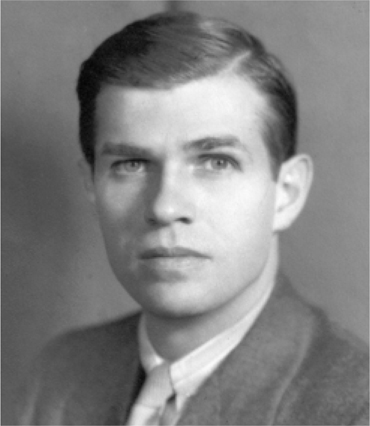

Alger Hiss as a young man.

This clearly would not do. The values of the Hesse-Darmstadts dated back to chivalry: fear God, never lie, fight injustice, protect the weak. When Alger was sixteen, his mother sent him to a prep school called Powder Point Academy, “where everything is bent toward developing self-mastery.” In two terms the runt turned into a gangly basketball player of six foot one, arms and legs all over the place but as good-looking as he was tall, deep-set eyes – very blue – dark hair, those high cheekbones, an elegant face, sharply defined, regular features. The Academy did serious work inside his head too; at the end of his time there, the yearbook said, “Alger is the epitome of success.” Johns Hopkins University followed. He took the place by storm, fanciest fraternity, president of the student council, member of Phi Beta Kappa and practically every other social and intellectual honour available to an undergraduate. He was voted the “most popular” in his class.

After that came Harvard Law School, where he shone so brilliantly that his illustrious tutor, Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter, recommended him for the job of law clerk to the even more illustrious Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes. Holmes was a popular figure, a Civil War veteran with a magnificent handlebar moustache, the most widely cited judge in US history then as now, famous for the phrase “clear and present danger” and for his courage as “The Great Dissenter”. Alger spent a year with him, “a celestial time” in his life, as he told his son long afterward. He read out loud to the great man, learned the secret of writing Supreme Court decisions. It’s like pissing, Holmes told him. “You apply pressure, a very vague pressure, and out it comes.”

That’s where he learned the deepest secret of his profession, the one he’d used to explain the basics of his case over crème brûlée at Dexter’s apartment. “This is a court of law, young man, not a court of justice.”

One of the conditions of working with Holmes was not to marry, but Alger married anyway. The woman was Priscilla Fansler Hobson, known as “Prossy”: heavy eyebrows and a strong jaw offset by gentle eyes, a widow’s peak and a lissom, graceful body made for sex. He’d been in love with her for years, but she’d married somebody else, had a child, divorced, not become available again until now.

Holmes promptly forgave the transgression and allowed them a whole weekend for a honeymoon.

The year with Holmes coincided with the 1929 stock market crash that brought on the Great Depression. Banks started collapsing so fast it makes our own shaky system look positively sturdy. Queues like the ones that stretched outside their doors at the beginning of our recent crunch, stretched outside thousands of banks all over the US. Reserves haemorrhaged at the rate of $15 million a day. The value of money lurched so erratically that global currency exchanges substituted a question mark for the dollar sign.

Nobody could keep track of unemployment either. Was it one person in six who wanted a job and couldn’t get one? One in five? One in four? Nobody knew. There were no welfare programmes to help – no unemployment benefit, no housing benefit, no health benefits – and no solution to hunger but breadlines, begging, soup kitchens, stealing, rioting, hobo jungles. With no money for food, mountains of it rotted. Farmers couldn’t earn a living; they rioted. Crime rates soared. No solution to cold either. Whole families huddled together in tar-paper shacks in ghettoes in every city, only to be moved on from plot to plot like the homeless of today. An aimless, hopeless, fearful time.

Businesses were collapsing right and left too, which meant that the need for lawyers was absolute; nobody came with better credentials than Alger Hiss. He went from Holmes to the most prestigious law firm in Boston, and he shone there as he had everywhere else. The Depression didn’t really touch him – except to bring in clients. The most important part of his life was Priscilla. He wanted her happy, and she wasn’t happy in Boston. She yearned for the excitements of New York City; in 1932 he transferred to a Wall Street firm.

As he wrote of himself later, “a not too uncharitable characterization” of his life up to this point “could well be the Progress of a Prig”. In Manhattan, richest of cities, he saw his first breadlines. He saw his first soup kitchens. He saw shantytowns in parks and vacant lots. He saw beggars on the streets. He watched the misery grow day by day, and he saw how shallow his upbringing had made him. He took on pro bono work in the hopes of using what he knew to help – only to realize how few remedies the law offered people in such a state.

The law needed changing, and Franklin Delano Roosevelt – running for President of the United States – proposed to do just that. Roosevelt was a snazzy Harvard graduate like Alger, but a seriously rich one, the only disabled person ever to come anywhere near the Oval Office. He was as spoiled as they come and almost too charming, but there was a profound optimism in him; they sang “Happy Days Are Here Again” at his rallies. He offered people a New Deal, and he captured American hearts; a third of the electorate switched parties to vote for him, the first Democrat in 80 years to win such a sweeping victory. It was in his inaugural address that he delivered that most famous line: “The only thing we have to fear is fear itself.”

Roosevelt had a wonderful brain, and his New Deal was a stroke of genius. As soon as he was in office, he had Congress enacting legislation with dozens of alphabet agencies covering every aspect of economic redevelopment. NRA: the National Recovery Administration. WPA: the Works Progress Administration. FDIC: the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. The New Deal’s extraordinary achievement is that it managed to string a tightrope between big business and the armies of young idealists, who saw communism as the only way to distribute wealth in a country where so many people were going hungry.

Maybe tightropes are dangerous, but they’re exciting. Alger’s old teacher Felix Frankfurter urged him to join. He was already euphoric over Roosevelt’s victory. He already saw that the New Deal was a crusade worthy of the chivalric code he’d grown up with, and this was a national emergency. He went to Washington in 1933 as assistant general counsel to the Agricultural Adjustment Administration, the alphabet agency AAA, set up to curb the power of the agricultural conglomerates and create a legal structure to support the individual farmers whose crops he had seen rotting in the streets. A big job, a job with serious authority, a “heady experience”. Alger himself helped draft legislation to give underprivileged Americans the legal remedies that New York had taught him they didn’t have.

He also became counsel for the Special Committee on Investigation of the Munitions Industry, chaired by Senator Gerald Nye: war-profiteering, the scandal of American businesses arming Hitler’s war machine. He did both these jobs with such ingenuity, enthusiasm and success that the Department of State came next, fulfillment of a childhood dream, assistant to the Assistant Secretary of Economic Affairs. World War II broke out. He rose to Special Assistant to the Director of the Office of Far Eastern Affairs, then to Special Assistant to the Director of the Office of Special Political Affairs, then to Assistant to the Assistant Secretary of State, then to Executive Secretary of the Dumbarton Oaks Conference.

That’s where the idea of the United Nations was born.

The Yalta Conference came in February of 1945, right near the end of the war. Yalta just has to be one of the most important conferences in modern history. The “Big Three” were all there in person: Roosevelt, Churchill and Stalin. The agenda was to coordinate strategy to defeat Hitler and Japan, decide how to divide up postwar Europe and how to punish the Nazis. Alger helped draft the treaty signed there, and he attended the conference itself as one of Roosevelt’s personal assistants. Photographs at the vast round table in one of the special “Big Three” meeting rooms show him right behind Roosevelt, three seats away from Churchill, straight across from Stalin.

They say that if you mount the wild elephant, you go where the wild elephant goes. Every one of those three was a wild elephant, and they all wanted to go in different directions. Roosevelt didn’t want Churchill to invade Japan – he’d demand more colonies when the war was over – but he did want to arrange invasion dates with Stalin. Roosevelt and Churchill wanted to ensure that Stalin didn’t make a separate peace with Germany and didn’t learn details of the atomic bomb that the US was developing. Stalin’s position was so strong he could demand almost anything he wanted from either of them; for the most part he got it, too. The atmosphere was so tense that when Anthony Eden, a mere member of the British delegation back then, went to take a pee and found Stalin in the line behind him, he sprayed the walls.

After Yalta, the peace-to-come preoccupied everybody. How to make it international? How to keep it? Alger was Secretary General of the San Francisco United Nations Conference on International Organization, which set up the United Nations itself. After the war ended, he was Director of the Office of Special Political Affairs: the search for ways to avoid World War III. He left the State Department to become President of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace: now the search was for a workable system of international law.

The Endowment was founded in 1910 by the robber baron and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie, whose Carnegie Hall is the pinnacle of any musician’s career. Nobel prizes for its two previous presidents had made the Endowment itself world famous. Its chairman John Foster Dulles was soon to be Secretary of State for President Dwight D. Eisenhower. Eisenhower himself was a board member. So was the founder of IBM. So was David Rockefeller, scion of the great Standard Oil family.

Such giddy heights belong in fairy tales. Where could such a man as Alger Hiss not go? No wonder everybody assumed that something as grand as Secretary of State had to come next.

Instead came two years of headlines like these from The New York Times:

AUGUST 4, 1948

RED ‘UNDERGROUND’ IN FEDERAL POSTS ALLEGED BY EDITOR

Ex-Communist Names Alger Hiss

DECEMBER 16, 1948

ALGER HISS INDICTED IN SPY CASE

JANUARY 22, 1950

MR. HISS FOUND GUILTY

JANUARY 26, 1950

HISS IS SENTENCED TO

FIVE-YEAR TERM