While Alger was getting ready to enter his cage at the West Street centre in New York for his first day as a Federal prisoner, posters were going up all over California:

LET’S ELECT

Congressman RICHARD NIXON

UNITED STATES SENATOR

The man who “Broke” the Hiss-Chambers

Espionage Case

Corrupt politicians and the Mafia go hand-in-hand. To this very day, wiseguys buy cops, FBI agents, judges, politicians. They control whole sections of cities and counties.

Mickey Cohen, Nixon’s mentor, wrote in his memoir that the original orders to support Nixon had come from “the proper persons back east”. These proper persons, he explained, were Meyer Lansky and Frank Costello, soon to consult Alger about his own conviction. A touching irony, but why would the Mafia choose Nixon? “If you were Meyer,” explained Senate crime investigator Walter Sheridan, “who would you invest your money in? Some politician named Clams Linguini? Or a nice Protestant boy from Whittier, California?”

In this senatorial race, our nice Protestant boy was facing Helen Gahagan Douglas, a beautiful woman pushing fifty, a Broadway star and opera singer, supporter of the New Deal and personal friend of Eleanor Roosevelt, Mr. Frank’s favourite political figure. But then as everybody knows, for the Mafia business is business: nothing personal. And that was the Fifties, the time of fluffy crinoline slips and dumb blondes, when women’s colleges in America made it clear that bagging a husband was more important than working for the degree they awarded. Helen Douglas was the first woman Democrat ever to be elected to Congress, and by the time of her race against Nixon, she’d been in government much longer than he had. She was a person of heart too. William Miller, the House of Representatives doorman who’d seen Nixon gearing up for the drama of the pumpkin, said of her, “Had she been able to stay in Congress, who knows what good things she could have done for the poor?” That was precisely the trouble. She was anti-big business, especially the oil companies. And the Mafia was heavily into oil.

Cohen reserved the Banquet Room in the Hollywood Knickerbocker Hotel. The guest list? “It was all gamblers from Vegas, all gambling money; there wasn’t a legitimate person in the room.” The aim was to raise $75,000, a considerable piece of money in those days. But while the crockery was being cleared away, Cohen’s business manager whispered in his ear, “Mick, we didn’t raise the quota. We’re short $20,000.” Cohen’s solution was to bar the exits and make an announcement: “Lookit. Everybody enjoyed their dinner, everybody happy? Well, we’re short of this quota, and nobody’s going home till this quota’s met.”

The quota was met. And then some.

The mob wasn’t alone either. The whole of corporate America wanted this woman out of California. Oil money poured into the Nixon campaign from as far afield as Texas and Indiana. Not that oil was the extent of it. Money funnelled through crooked cracks in big business all over the country, lumber money, liquor money, bank money. Documents at the Nixon Library suggest campaign funds overall ran to $200,000. But billboards alone ran to $50,000. Television, well beyond the reach of most candidates back then, was crammed with ads for Nixon. One mere fortnight saw thirty-three Nixon spots on three San Francisco stations. Some estimates put the full figure at more than $4 million, a fabulous sum, something like ten times that amount in today’s money. There was so much cash that the mob was handing out $100 bills at fundraisers for other Republican candidates.

Nixon promised another “rocking, socking” campaign based on hard work, surprise and keeping the opponent on the defensive. He gave instructions that audiences were to scream hysterically whenever he appeared. Skywriting planes wrote “NIXON” across the skies above beaches. A Nixon rally in central Los Angeles promised door prizes for everybody who attended. Blimps dropped leaflets that promised voters – as he had in his second Congressional campaign – that if they answered the telephone with the words, “Vote for Nixon”, and if the call came from Nixon headquarters, they could win

PRIZES GALORE

Electric clocks, Silex coffee makers with heating units-General Electric automatic toasters-silver salt and pepper shakers, sugar and creamer sets, candy and butter dishes, etc., etc.

Four-page ads in newspapers showed Nixon as the “ardent American” and “the perfect example of the Uncommon Man”. The Los Angeles Examiner’s editorial cartoon took up a whole half page: Nixon with bulging biceps, a shotgun in one hand, a net labelled “Communist Control” in the other. Our hero was guarding a wall called “National Security”. Behind it American farms and factories huddled. Running away in terror were rats labelled “Appeaser,” “Propagandist,” “Soviet Sympathizer”.

Its caption: “ROUGH ON RATS!”

Nixon dubbed Helen Gahagan Douglas “The Pink Lady”. He printed anti-Douglas fliers on pink paper; he said she was “pink right down to her underpants”. He advertised her as “Helen Gahagan Douglas, Alger Hiss’s pet.” An onslaught of anonymous phone calls: “Did you know that Helen Douglas is a Communist?” A Methodist minister who supported her had to take his phone off the hook; just supporting her invoked a barrage of “You’re a Communist” accusations. A second telephone campaign ran alongside the first: “Did you know Helen Douglas is married to a man whose real name is Hesselberg?” Her husband, a famous actor at the time, was a Jew. Newspapers printed pictures – many years old – of her with Paul Robeson, the “black Stalin”.

It wasn’t just a matter of words, pictures and money either. Nixon’s people seized Douglas’s fliers and dumped them in the ocean. Nixon hecklers shouted her down at every stop on speaking tours, doused her in seltzer water right as she spoke, pelted her with red ink, tossed rocks at her car.

And Nixon the Lucky struck lucky yet again with war in Korea. In summer, the communist state of North Korea had invaded the very corrupt but democratic South. UN troops, heavily supported by the US Army and Navy, forced them back across the border, but on the very eve of the California election, Communist China intervened. Or so it seemed. The picture was murky. Information conflicted. When a newspaper editor asked the senatorial candidates if under the circumstances they supported China’s entry to the United Nations. Nixon shouted, “No!” Douglas hesitated.

“This is the final straw,” Nixon thundered. “Doesn’t she care whether American lives are being snuffed out by a ruthless aggressor?”

His win was another landslide.

Another winner who owed his career to Alger was America’s Witch Finder General, Senator Joseph McCarthy of Wisconsin.

He’d been as obscure as Nixon in the pre-Alger days, a boozing, foul-mouthed Nazi-lover voted “the worst U.S. senator” currently in office by the Senate press corps. While Alger’s conviction filled the headlines, a drunken McCarthy reeled onto a stage to give a Lincoln Day speech to the Republican Women’s Club of Wheeling, West Virginia.

The Club had expected talk of housing, schools, roads. Instead they got a rant lifted straight from a speech of Nixon’s: there was a “spy ring” at the heart of government” that “permits the enemy to guide and shape our policy”. McCarthy held up a piece of paper. “I have here in my hand a list of two hundred and five: a list of names that were made known to the Secretary of State as being members of the Communist Party.”

The press went so crazy, McCarthy didn’t know how to handle it. “Listen, you bastards,” he shouted at them, “I’ve got a pail full of shit and I’m going to use it where it does me most good.” In Salt Lake City, Utah, a few days later, he lowered the number to fifty-seven. A few days after that in a Senate speech, he raised it to eighty-one, said he could present a case-by-case analysis of them all.

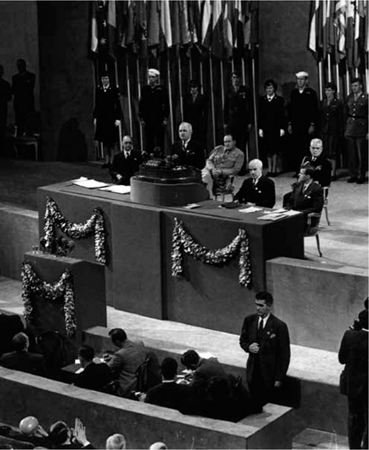

The final day of the United Nations Organizing Conference, June 26, 1945: Alger Hiss (seated on the dais, far right), Secretary General of the Conference, listens as President Harry S. Truman addresses the delegates.

McCarthy was Nixon on crack. Two hundred and five Communists? Boot them out. Eighty-one loyalty risks? Name them, shame them. Fifty seven spies? Toss them in prison. Precise numbers flew out of the Senator’s mouth: 238 witnesses, 367 and more and more. Father Cronin, Nixon’s informant on the subject, wrote of “mass espionage motivated…merely by fanatical devotion to the Soviet Union.” People were scared over their neighbourhood fences. Are the Joneses secret Reds? Are the Smiths? “Twenty years of treason” – McCarthy’s epithet for the Roosevelt and Truman administrations – had left the country diseased. J. Edgar Hoover, Director of the FBI, said American families were being “infiltrated, dominated or saturated with the virus of communism”. That’s when Nixon’s right-hand man Stripling wrote that this virus brings Soviet Communists into “complete control over the human mind and body, asleep and awake, in sickness and in health, from birth to death.” Another HUAC Republican announced that “communism would make a slave of every American man woman and child.” Children as safely across borders as Canada started going to bed at night too frightened of Communists to turn out the lights.

McCarthy easily won back his Senate seat. All the Republicans he supported won. He became one of the most powerful men in the Senate. “We Americans live in a free world,” he said in a television speech, “where we can freely speak our opinions on any subject, or on any man.”

Some 30,000 un-American books were removed from library shelves. Several libraries went all the way with public pyres just like the Hitler Youth with their unGerman books. The government in The Wizard of Oz was Marxist. The Adventures of Robin Hood advocated the Communistic idea of distributing wealth

Hundreds of teachers in New York alone lost their jobs for “disloyal” activities. Thousands of teachers across the country. Thousands of union members. McCarthy’s specially targeted victims made up a list of America’s most gifted that was even longer than HUAC’s; it included such luminaries as Albert Einstein, Thomas Mann, Leonard Bernstein, Charlie Chaplin, Sam Wanamaker, Aaron Copeland, Jules Dassin, Allen Ginsberg, Arthur Miller, J. Robert Oppenheimer, Linus Pauling, Paul Robeson, Louis Bunuel, Orson Welles. The government ordered an investigation into the loyalty of three million government workers, and terror in the State Department became a Washington joke: “A newspaperman walks up to a US diplomat and asks him what time it is. The diplomat looks over both shoulders and whispers, ‘Sorry, no comment.’”

President Truman, speaking at Detroit’s 250th anniversary celebration, told his audience that on the Fourth of July in Madison, Wisconsin, “A hundred and twelve people were asked to sign a petition that contained nothing except quotations from the Declaration of Independence and the Bill of Rights. One hundred and eleven of these people refused to sign that paper – many of them because they were afraid that it was some kind of subversive document and that they would lose their jobs or be called Communists.”

I knew three people who got caught much as these feared they might be.

The first was Kate Way, the physicist who’d co-edited One World or None with Dexter. She was a feisty, independent-minded woman who’d once told me that the best love affair she’d had in her life – she’d had many – started just after her seventieth birthday. She was a physicist, an expert in atomic spin – the way atoms dance inside molecules – and she’d been one of the few women physicists to work on the Manhattan Project that manufactured the first atom bombs. She left government work after the war, co-edited that book with Dexter, and went on to help establish and produce two magazines – Nuclear Data Sheets and Atomic Data and Nuclear Data Tables – that I remember as nothing but rows of figures like tables of logarithms. One day she received a subpoena to appear in front of a grand jury in New York to answer charges: she’d attended a Communist meeting a decade before on a given date at a given place. Kate had no interest in politics. None. She’d never attended a political meeting, this one or any other.

“It’s perfectly simple,” she said to her lawyer. “I wasn’t there.”

“Where were you?” said the lawyer.

How could she possibly remember something like that?

“Then I’m afraid it’s not so simple.” He told her that the only way she could clear herself was to find somebody else who

• had attended that meeting;

• had been a Communist at the time;

• was no longer a Communist;

• remembered who was there and who was not;

• and most important, was willing to testify on her behalf.

Kate was a determined woman. Also she’d inherited money, a lot of it. She spared no expense. She hired teams of detectives. After an intensive search, they located a potato farmer in the Midwest who fitted all the requirements. There was just one snag. He had a crop to get in. He told the detectives to get lost.

Kate went herself. She walked across an acre of newly ploughed field, stood in front of his tractor until he’d agree. He flew to New York and testified. The charge against her was dropped – only to reappear a year later in exactly the same form. Again she cajoled the potato farmer into testifying. Again the charge was dropped.

It was brought a third time the following year.

My father’s first wife, Dorothy Stahl, got caught too. She was a mathematician with the Department of Labor in Washington. Her transgression was her marriage to my father even though they’d been separated for quite some time when the FBI started questioning her about him. She defended him; a couple of her statements survive in his file. The result? She lost her security clearance and with it her government job.

My father’s own troubles began like Kate’s. An unknown somebody said he’d been present at a meeting of the Communist Party in Los Angeles on a given day more than a decade before. He was lucky here. On that very day, he’d been delivering a well-publicised speech in San Francisco.

But he didn’t stay lucky. Red-baiting brought more and more Republicans into Congress, and the Democratic administration couldn’t hold out against the tide any longer. President Truman issued Executive Order 9835 prohibiting Federal employees from “sympathetic association” with Communists. The states followed quickly with HUAC-like panels that launched into teachers, cops, firemen, longshoremen, administrators, writers, artists. Americans with FBI files in local or national offices or both soon numbered in the hundreds of thousands.

The very first university to indulge in the new frenzy was the University of California – Nixon’s home state – where my father taught economics. The Regents presented the staff with a Loyalty Oath. “Sign or get fired,” they said. The vast majority of staff saw such oaths for what they were, a frightening step in the direction of Nazi thought control. Instil fear, division, compliance. Take away the right to independent thought, and people will stay under your thumb. Nothing could be further from the ideals of a university, and back then those ideals still had a little meaning.

The staff met. My father spoke. He had a strong, resonant voice with movement in it – something of those Biblical rhythms that make Obama such a powerful speaker – and there was nothing he felt more passionate about than the encroachment of fascism in America. He proposed a solution. Stick together. Refuse to sign as a group. His audience took a vote and agreed almost unanimously. A protest began.

All of this is missing from his FBI file. There’s not a single mention of the oath despite massive press coverage of it at the time. The only hints at its existence are those threats of deportation.

The Regents remained firm; the dissenters gained ground. The protest movement faltered, then collapsed. Faculty signed in droves. “I’ve thought of a motto to put over Berkeley’s new faculty building,” said my father’s friend Max Radin, Professor of International Law. “Remember The Wind in the Willows? Mole spends a terrifying night in the forest pursued by beasts. The next day, the rabbits come out of their holes and admit that they knew all about it. ‘So why didn’t you help?’ Otter asks. ‘What, us?’ said the rabbits. ‘Do something? Us rabbits?’ Now, that’s what belongs over the new faculty building door:

“‘What, us? Do something? Us rabbits?’”

While I was working on this book, I checked a website devoted to Berkeley’s loyalty oath. Thirty-one faculty members held out against the Regents. I’d thought it was only my father and Max. What the hell, it was still very impressive. I asked my sister Judy if she’d realized the two of them weren’t alone.

“Joanie, he signed.”

“He did not.”

“Of course he did, you dope. He kept his job.”

There are matters of pride that hold a life together. This intransigence of my father’s had been one for me. The only virtue in losing it was that I had an explanation for what had been inexplicable before.

One night, he swallowed close to twenty-five grams of Phenobarbital. It’s a dose that could have killed ten men. The effect wasn’t at all what he’d planned; the barbiturates stunned his gut. He couldn’t absorb them. He survived – a miracle that made medical history – but they caused a massive stroke that paralyzed his body and destroyed his brain. He couldn’t write or read or understand, not written words or spoken ones. The only phrase he could come out with – for pain or humiliation or gratitude or love – was “a cup of coffee”.