Image Gallery

James Earl Ray was born in the basement of this two-room house in the rough blue-collar town of Alton, Illinois.

Ray (left) at fourteen. By this age, he had already been picked up by the police for petty theft and had started visiting prostitutes and bars with his uncle Earl, a convicted felon.

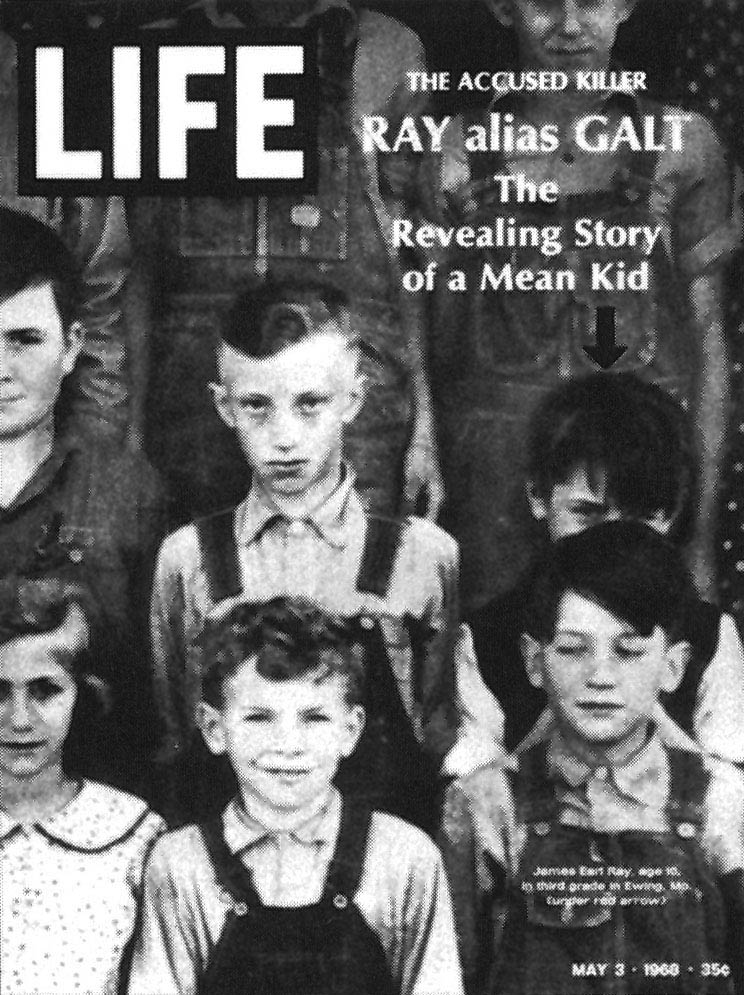

After the assassination, much of the press coverage focused on Ray’s tough upbringing in a poor white family with a nearly one-hundred-year history of criminal behavior. Life’s cover story on young Ray (partially hidden on the right, second row) was one of the harshest portraits, describing him as a young bully who could not stay out of trouble.

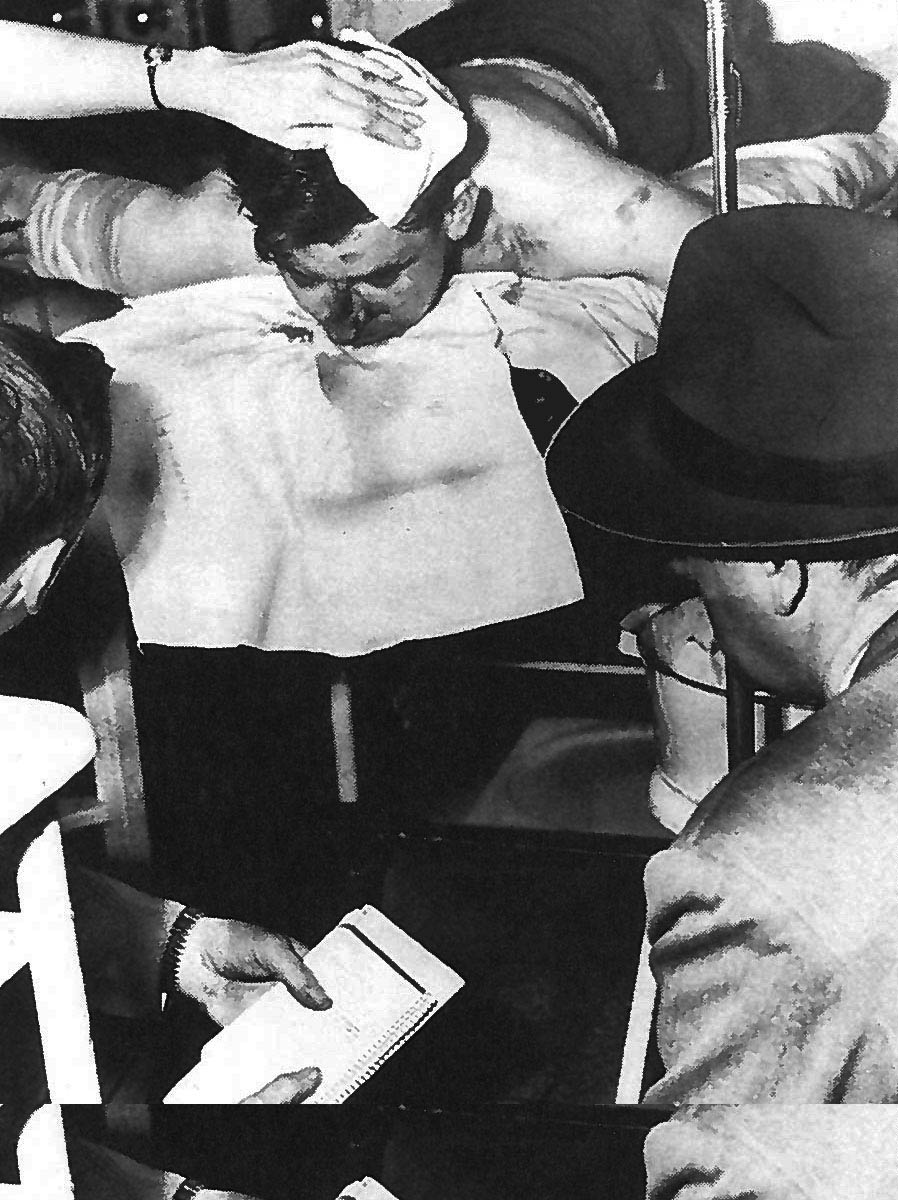

Ray botched a 1952 armed robbery of a taxicab in Chicago, and was shot in the arm by police before he surrendered after a wild chase through city streets. This was his third adult arrest, and he spent twenty-two months in state prison for the crime. (AP/Wide World Photos)

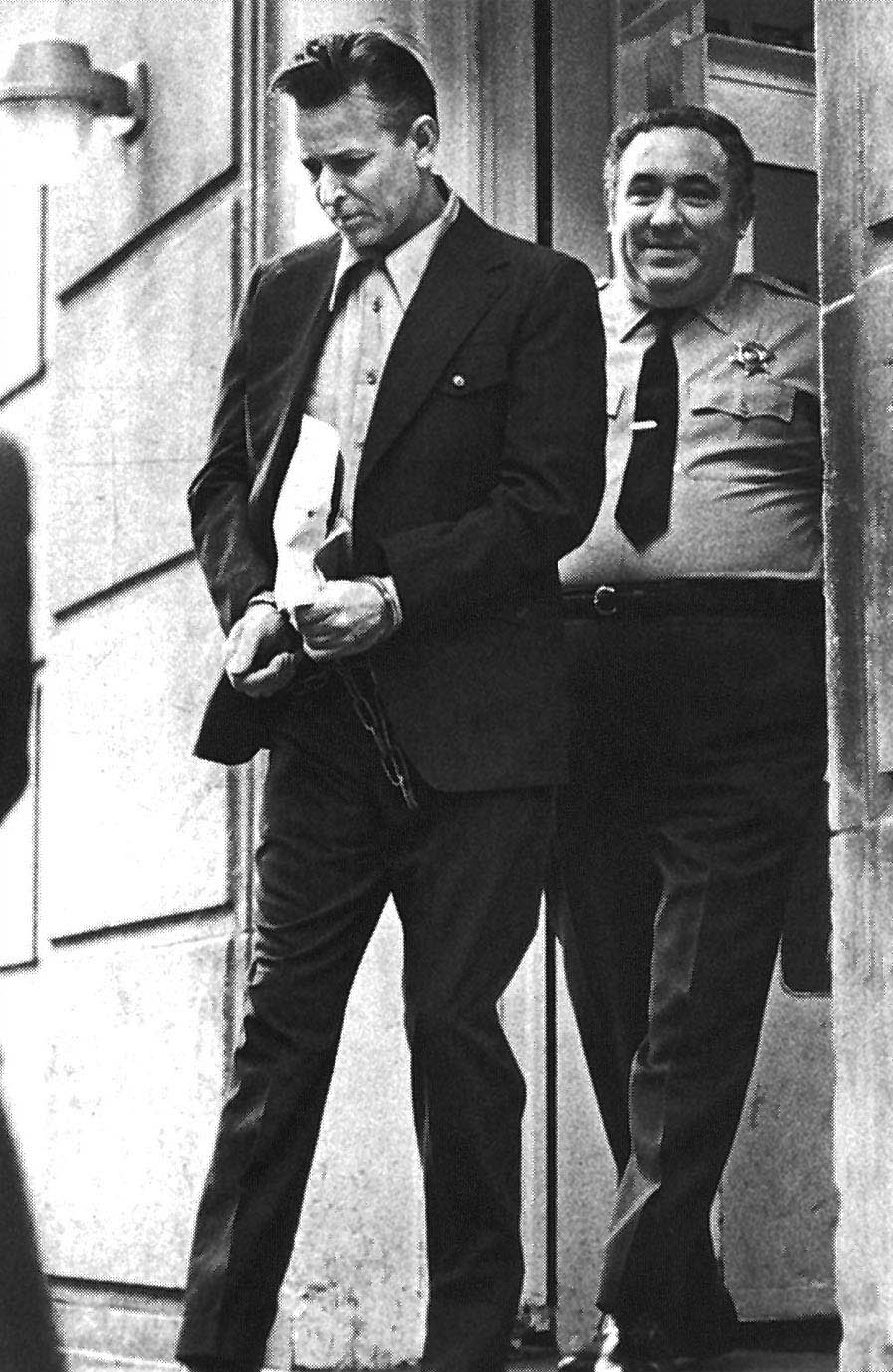

Although he pulled dozens of successful robberies during the 1950s, Ray’s luck again turned bad in 1959, when he was arrested for several supermarket robberies. Since it was his fourth major offense, the thirty-two-year-old Ray was sentenced to twenty years in prison. (AP/Wide World Photos)

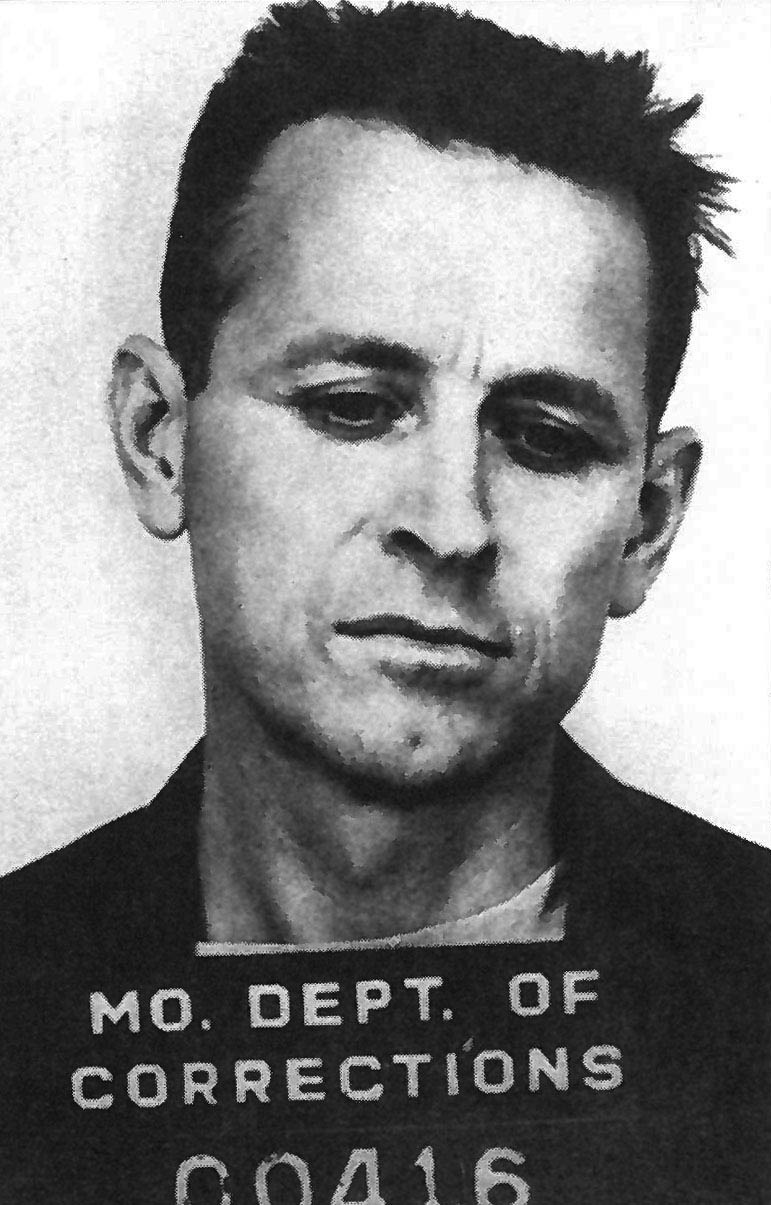

Ray as he looked in 1960 when he entered Missouri State Penitentiary, one of the toughest prisons in the United States. There he developed a reputation as a “merchant,” dealing in drugs and other contraband. He was also known as a racist who abused drugs himself, primarily amphetamines. (FBI copy of Missouri State Penitentiary photo)

Six years later, in 1966, Ray looked gaunt and haggard, perhaps from his drug abuse. That same year he made his second unsuccessful escape attempt. On April 23, 1967, Ray finally broke out. (Prison photo, Missouri Corrections)

After escaping from prison in April 1967, Ray threw police off his trail by moving frequently across the United States and Canada, as well as Mexico, where he was when this picture was taken. It was during these travels that Ray later claimed to have met a mysterious man he called Raoul, who would later be at the center of his defense in the King assassination. (AP/Wide World Photos)

While in Mexico, Ray spent most of his time in Puerto Vallarta in the company of prostitutes. Among them, Manuela Aguirre Medrano, who used the professional name Irma La Douce, was with Ray the most. According to some who met him there, he also smuggled marijuana and took racy photos of some of the women. (House Select Committee on Assassinations)

In his fugitive year leading up to the assassination, Ray spent nearly five months in Los Angeles. A habitué of local bars and flophouses, Ray also visited hypnotists and psychologists, took dance lessons, had plastic surgery, and attended bartending school. For his March 1967 graduation photo from the International School of Bartending—taken only a month before the assassination—Ray closed his eyes, with the hope that it might make him difficult to identify. An FBI sketch artist drew the eyes on the photo. (FB)

Tensions were high in Memphis after 1,300 sanitation workers, most of them black, defied the mayor’s order and went on strike in February 1968. A spontaneous February 28 demonstration for the strikers ended in violence when the police rioted, gassing and clubbing citizens. That provoked an outcry and led directly to Martin Luther King, Jr.’s decision to become involved in the Memphis strike. (Mississippi Valley Collection, University of Memphis)

Martin Luther King, Jr., and Ralph Abernathy (right) begin a march through Memphis on March 28, 1968. Young agitators in the crowd started breaking windows, and the protest soon turned violent, prompting the Tennessee governor to send in 4,000 National Guardsmen. King, sickened by the violence, vowed to return quickly to Memphis for another demonstration. (Mississippi Valley Collection, University of Memphis)

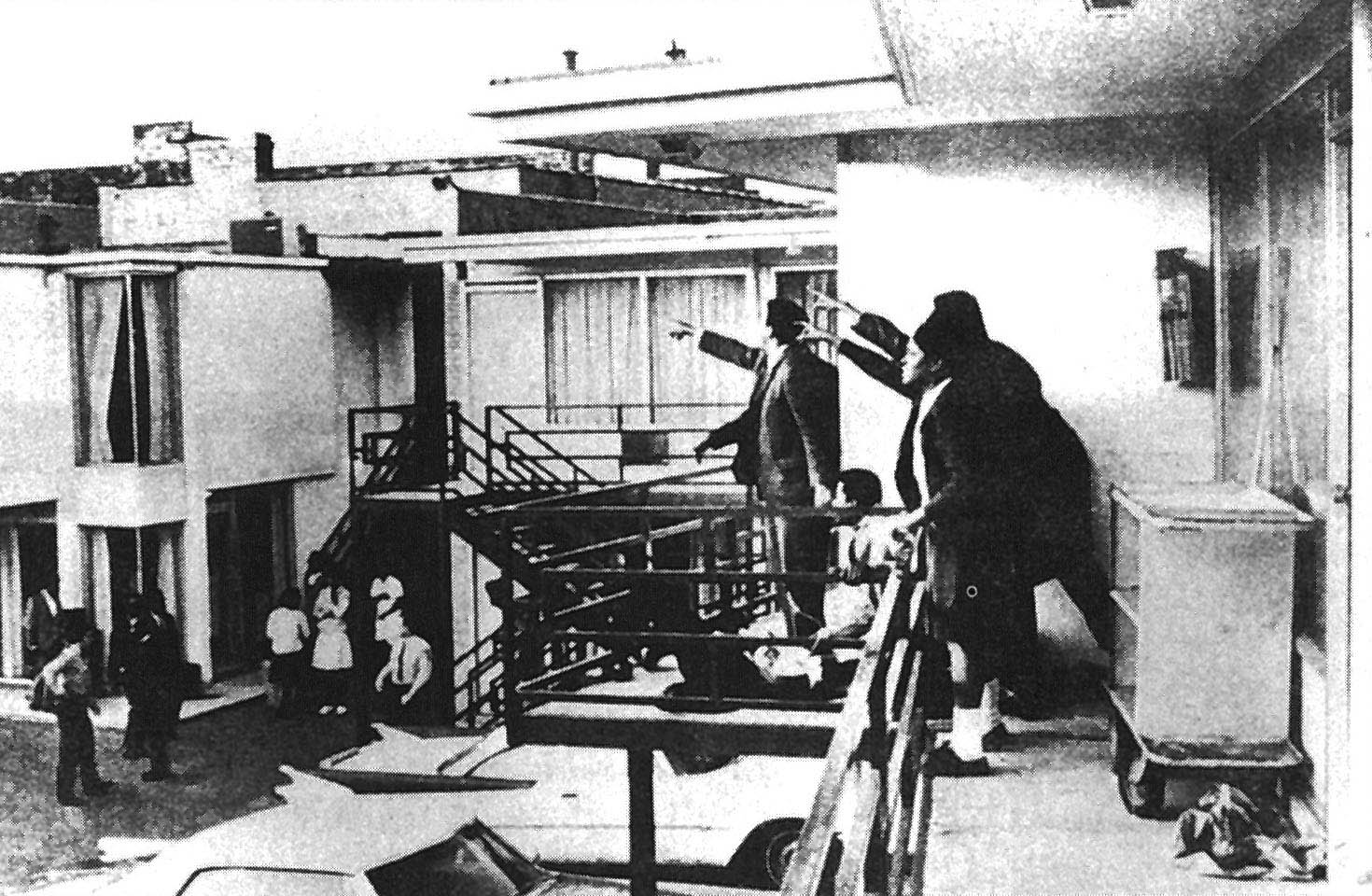

At 6:01 P.M., on April 4, 1968, Martin Luther King was shot as he leaned over the railing of the balcony that ran in front of his motel room. Within minutes of the shooting, King’s aides and friends, who had run to his assistance (King is lying on the floor), greeted police by pointing in the direction from which the shot had originated. (House Select Committee on Assassinations)

What most of the eyewitnesses immediately pointed to was the rear of two buildings, about eighty feet up a low slope across the street from the motel where King was staying. The buildings comprised separate wings of the flophouse where James Earl Ray, using an alias, had rented a room only three hours before the assassination. The window circle on the right is the bathroom from which the shot was fired. (Attorney General File)

After Ray fled the scene of the assassination, police entered his room and discovered that the dresser and mirror had been moved away from the open window and replaced by a chair. Someone leaning slightly out the window could observe Dr. King’s room at the nearby motel. (AP/Wide World Photos)

Within a couple of minutes of the assassination, the police discovered a bundle in front of a store doorway underneath the rooming house. It included a rifle bought five days earlier by Ray. His fingerprints were on the gun and telescopic site, as well as other items in the bundle. (House Select Committee on Assassinations)

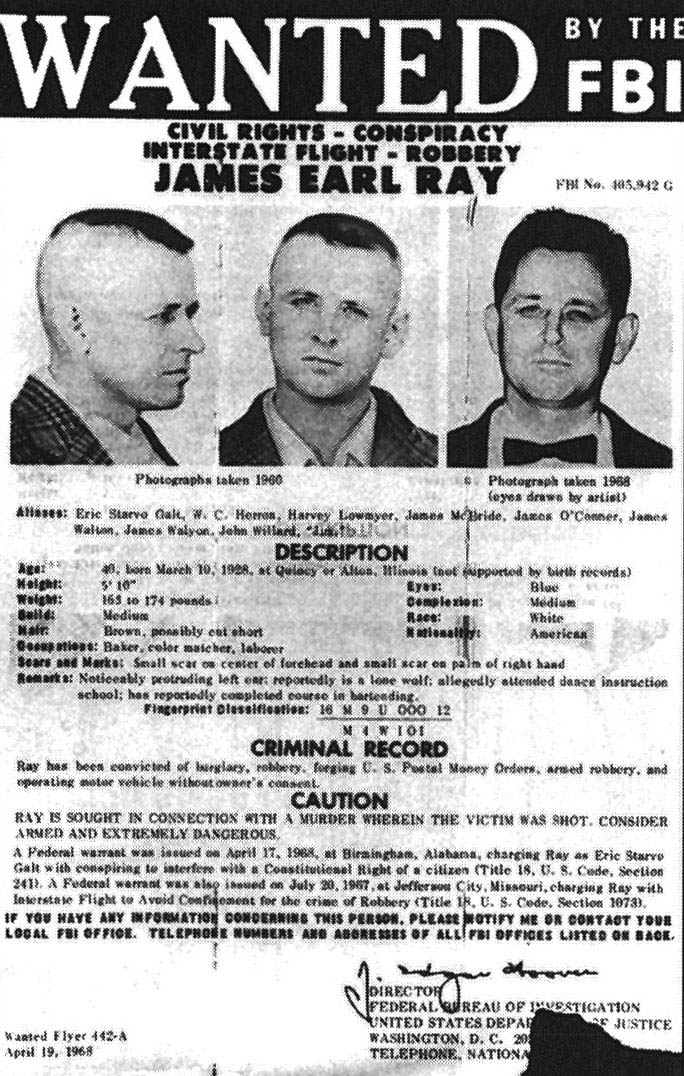

The FBI identified Ray from fingerprints and released a wanted poster for him fifteen days after the assassination. By then, he was hiding in Toronto, Canada. Ray applied for birth certificates of local Toronto residents Paul Bridgman and Ramon Sneyd. Living near those men was Eric Galt, whose name Ray had used during most of the year leading up to King’s murder. Some conspiracists have claimed that the three Canadians bore a remarkable resemblance to Ray, implying that the names were supplied to him as part of a sophisticated plot. But, in fact, beyond being middle-aged white males, they do not look much like Ray. (FBI file copy of wanted poster)

Paul Bridgman

Ramon Sneyd

Eric Galt

Ray obtained a Canadian passport in the name of Ramon George Sneyd. He then visited Portugal and England, trying in vain to join a mercenary group fighting in Africa. On June 8, 1968, sixty-five days after King’s murder, an alert British policeman spotted the name Sneyd on a watch list at Heathrow Airport as Ray tried to board a plane for Brussels. He was arrested and extradited back to the States that summer. (House Select Committee on Assassinations)

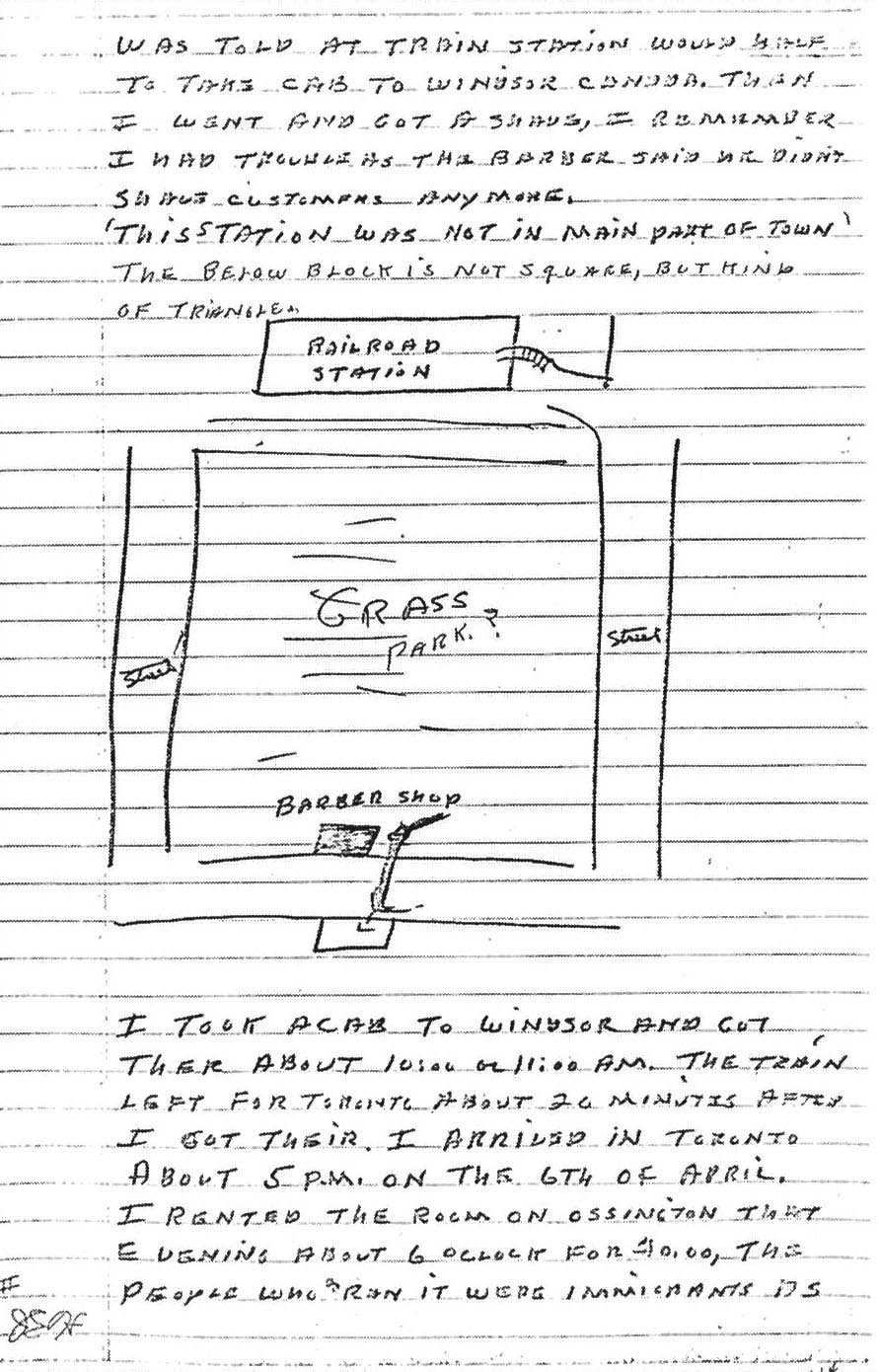

Ray’s first attorneys were Arthur Hanes, Sr., the former mayor of Birmingham, and his son, Arthur Jr. (above center). William Bradford Huie, a well-known writer (above right), signed a contract with the Haneses and Ray to obtain Ray’s exclusive story and for all of them to split any profits. Barred from interviewing him in prison, Huie received Ray’s story in handwritten notes and letters (right), which because of their cumulative size were called the 20,000 Words. Ray fired the Haneses just before his trial was to start in October 1968, and hired famed Texas trial lawyer Percy Foreman (above left). (Mississippi Valley Collection, University of Memphis; sheet of Ray’s writing: House Select Committee on Assassinations)

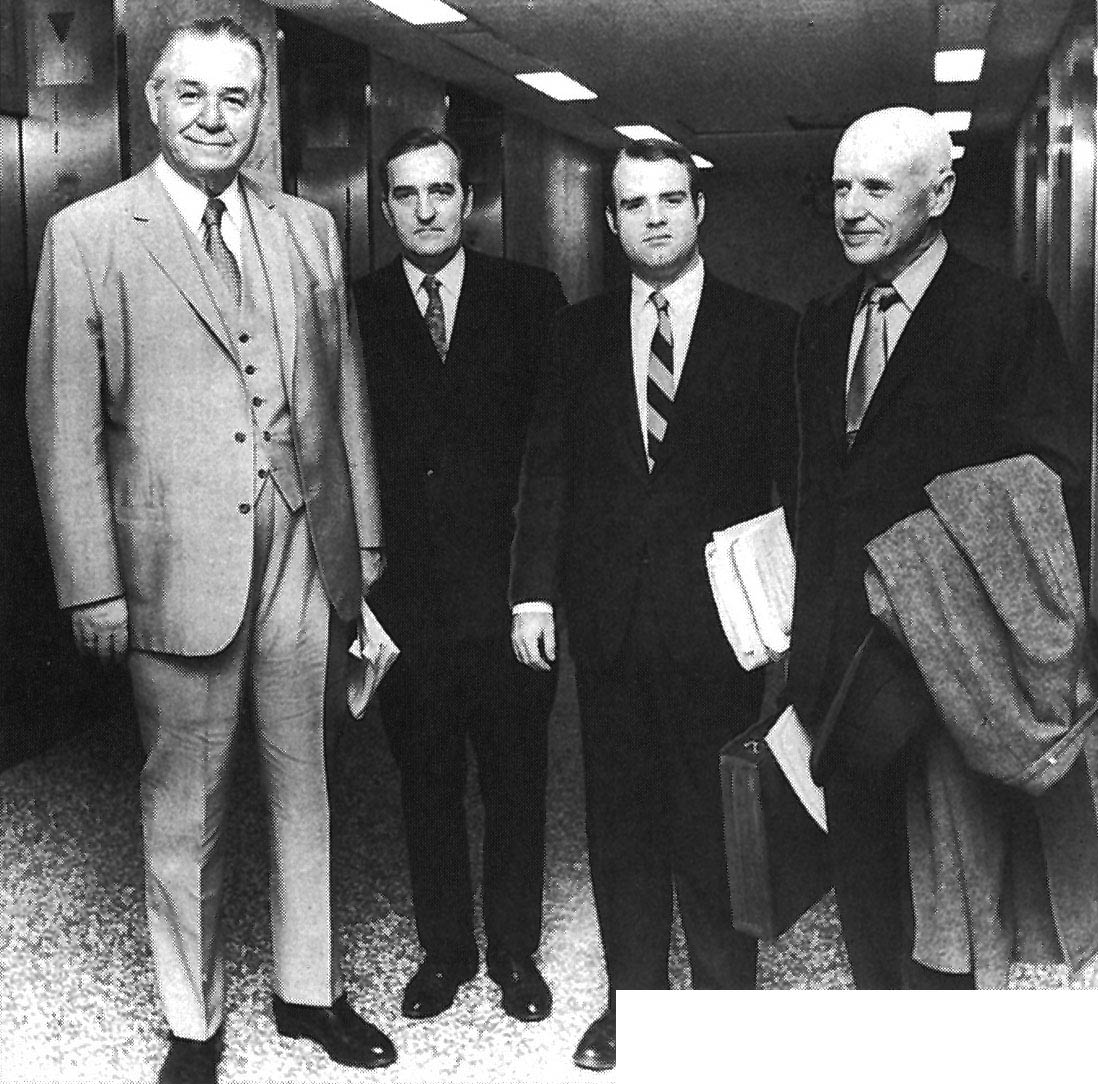

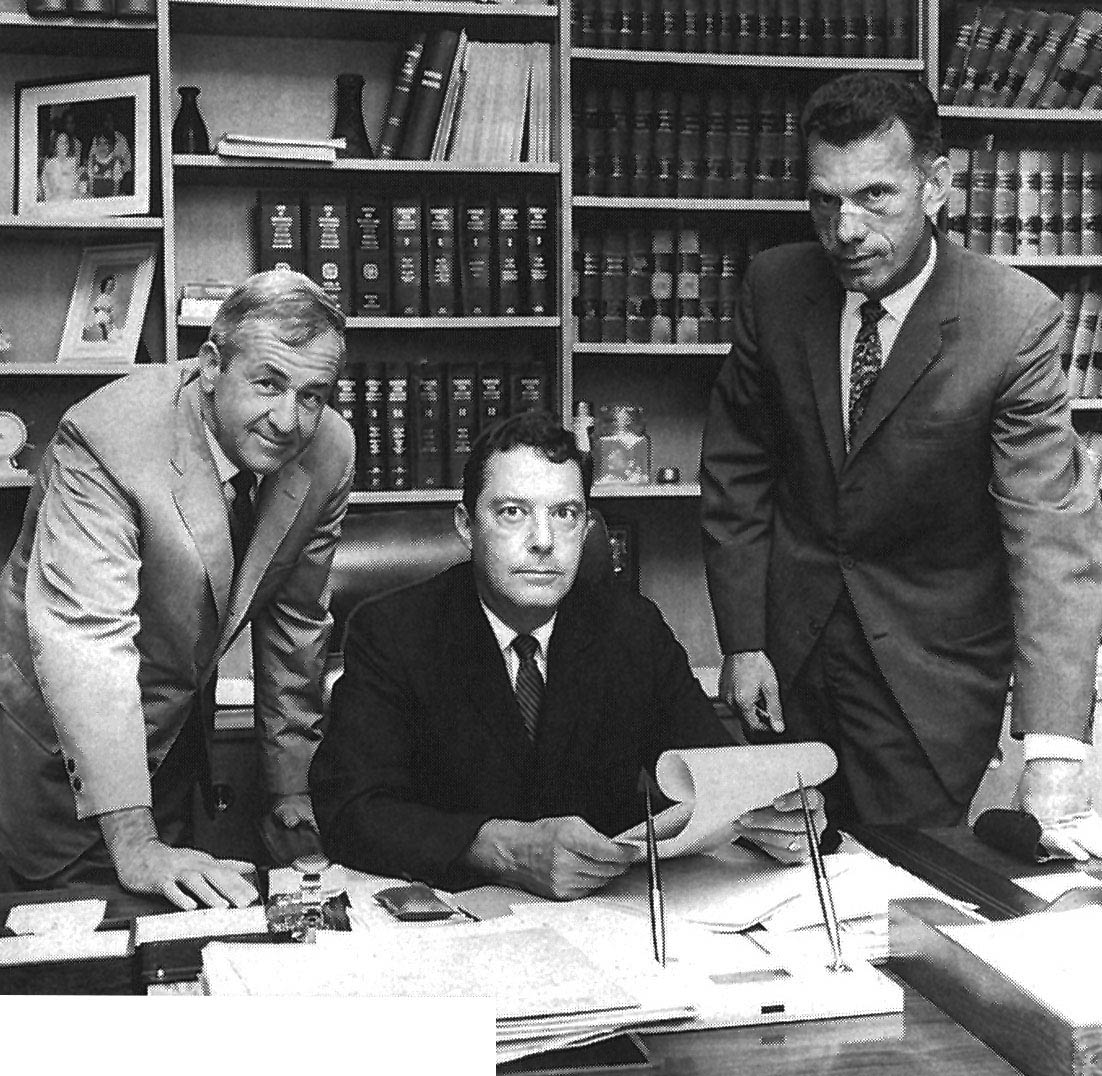

The prosecution team: District Attorney General Phil Canale (center), Executive Assistant Attorney General Robert K. Dwyer (left), and Assistant Attorney General James C. Beasley. Dwyer and Beasley were disappointed that they could not obtain a death penalty conviction. (Mississippi Valley Collection, University of Memphis)

Three days after his guilty plea, Ray wrote the trial judge, recanting the plea and asking for a new trial. It was the beginning of three decades of herculean legal efforts by Ray and a broad assortment of attorneys to win his freedom. (Mississippi Valley Collection, University of Memphis)

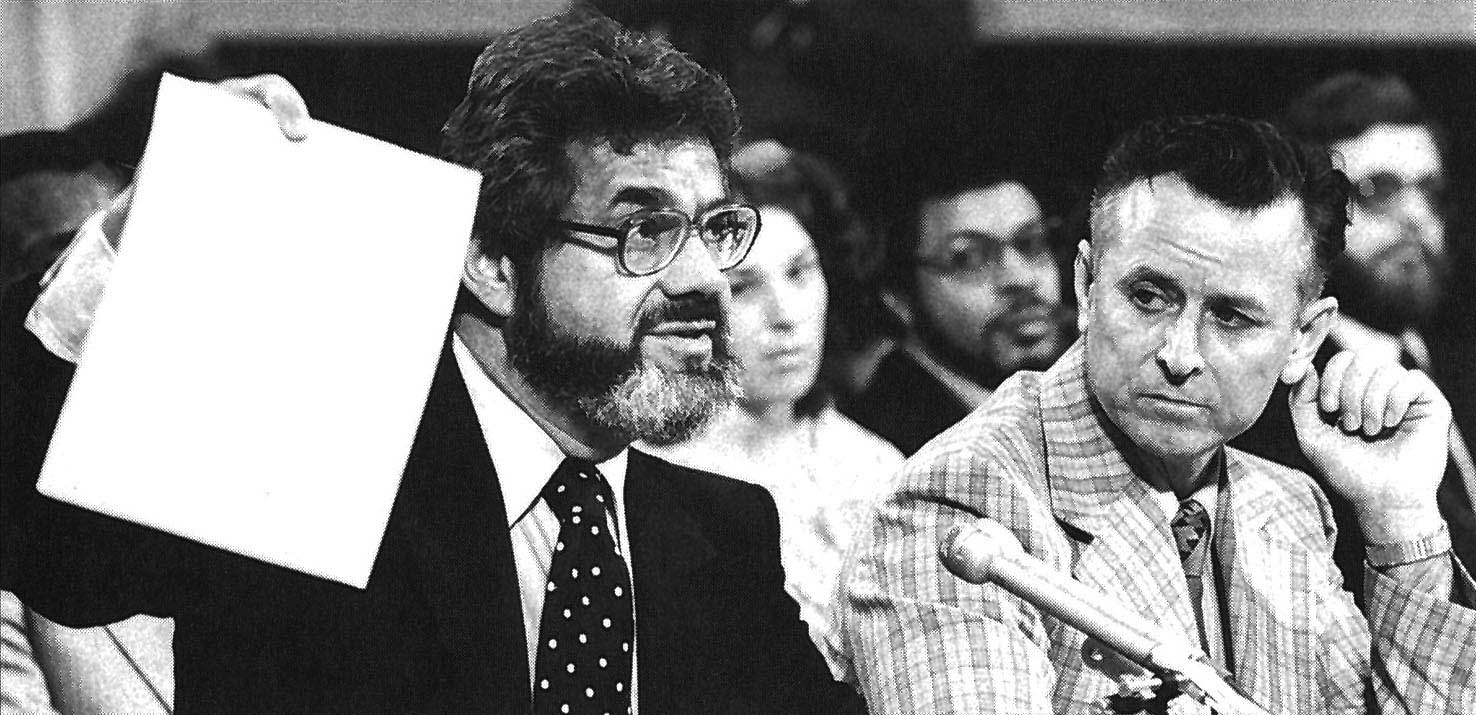

J. B. Stoner (center), one of the country’s most virulent racists, became Ray’s attorney in 1969. Ray’s brothers John (left) and Jerry (right) joined Stoner for an impromptu 1969 press conference in Memphis. The House Select Committee on Assassinations investigated whether either brother had any involvement in the assassination. (AP/Wide World Photos)

In the late 1970s, when Ray appeared before the House Select Committee on Assassinations, he was represented by Mark Lane, a caustic conspiracy buff who had earlier written a book contending that Ray was a patsy. (AP/Wide World Photos)

William Pepper (center), Ray’s latest lawyer, as he was confronted in 1997 by two retired military officers, Colonel Lee Mize (left) and Major Rudi Gresham (right), over Pepper’s charges that a military sniper team was in Memphis on the day King was killed. (Courtesy of Rudi Gresham)

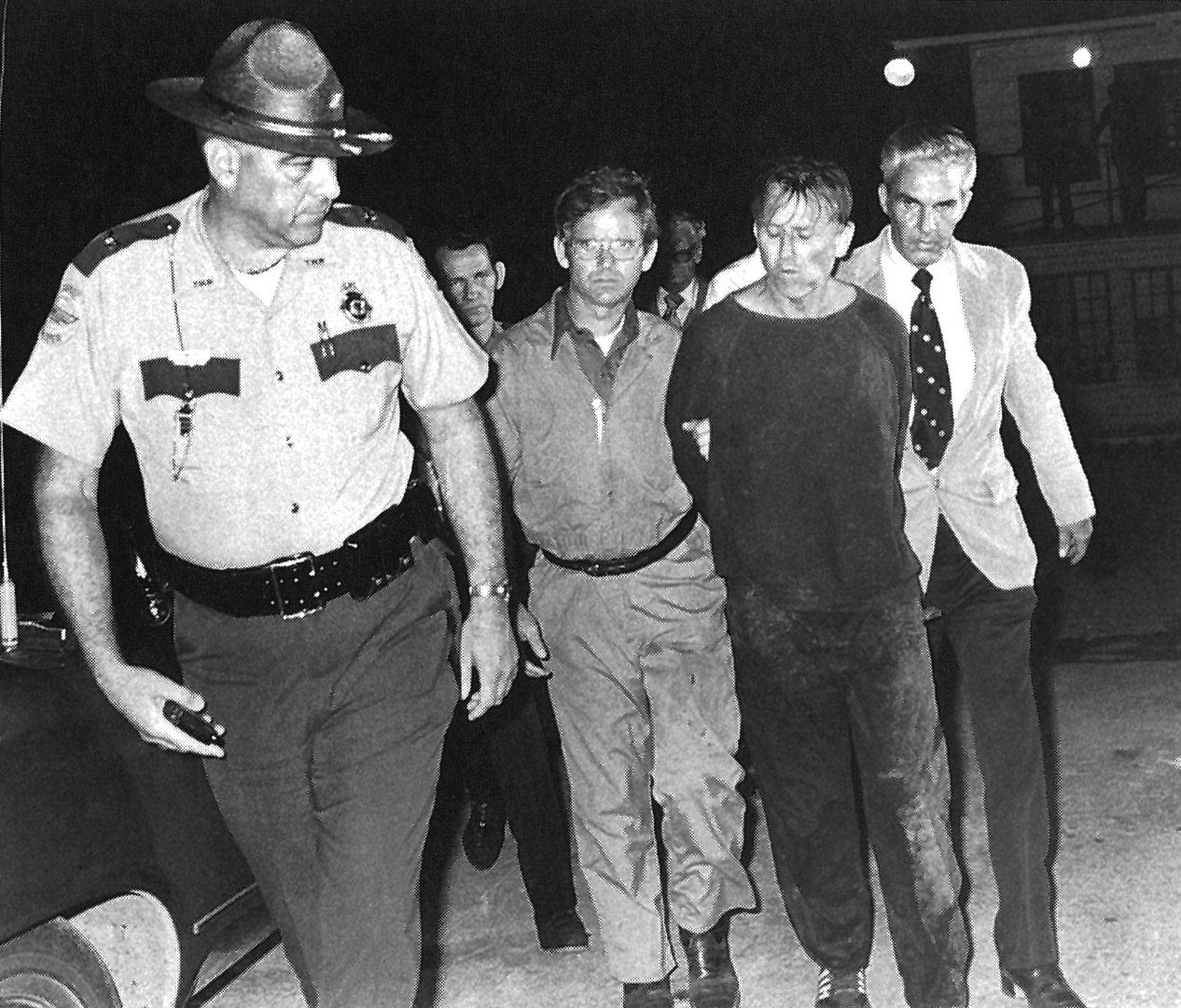

In 1977, Ray made a successful breakout from Brushy Mountain State Prison. It was his second attempt since pleading guilty to killing King. More than 125 prison guards, state troopers, and FBI agents, assisted by bloodhounds, combed through the thick wilderness in search of Ray, who was found only five miles from the prison, fifty-five hours after he escaped. (AP/Wide World Photos)

In one of the bizarre turns in Ray’s unusual life, during his 1977 trial for the escape, he met courtroom artist Anna Sandhu (right, appearing on Today with Jane Pauley in 1978). The two married, and she campaigned for his freedom—until she suddenly filed for divorce in 1990. She has said that the real reason she divorced Ray was that during a phone argument, she told him, “I’ve never believed you could have killed Martin Luther King,” and Ray yelled, “Yeah, I did it. So what?” and then slammed down the receiver. (AP/Wide World Photos)

On Thursday, March 27, 1997, Martin Luther King’s son Dexter met with James Earl Ray in his Nashville prison. Ray’s attorney, William Pepper, had urged Dexter King—who believes that a massive government conspiracy killed his father—to meet the confessed killer. During their meeting, Ray denied killing Dr. King. “I believe you, and my family believes you,” said Dexter. (AP/Wide World Photos)