SEVEN

Liquid Currency

The more bees you have, the more money you make.

Donald Smiley

Nothing but honey is sweeter than money.

Benjamin Franklin

Weather and bees permitting, with 700 hives Donald Smiley can harvest and sell about 180 barrels or 115,000 pounds of honey in a really good year. With bulk prices for tupelo averaging around a dollar-fifty per pound, one might guess that he was becoming swiftly and sweetly rich in a town where the median income is $26,000. He’s doing fine, but he’s not getting rich. Each of his hives grosses about $150 in sales, but labor and expenses per colony can be as high as $100 annually. With healthy hives and clement skies, he nets about twice the median income of Wewahitchka. “When I was just getting started, with a few hundred hives, I was barely breaking even every year,” he says. “Now I’m doing all right.” To do even better, he wants more bees. To support more bees, he’ll need more yards and equipment and a bigger honey house. “Right now I got a poor man’s honey house,” he complains with a smile. “It’s too difficult to get the bottling done at the same time as you’re harvesting. I really need a separate place to bottle my honey. Then I’ll be a big-time honey producer.” He’s started clearing the wooded lot behind the pink house to make way for the big-time facilities, although he’s not sure when he’ll have the time or money to build. When the grand new honey house is finished, he’ll use the poor man’s for bottling and storage.

To finance his expanding operation, he makes sales calls to grocery stores, produce markets, and tourist shops in the Wewahitchka area and travels as far as sixty miles north to Dothan, Alabama, distributing his wares. Business is best during July and August, when tourists from Alabama and Georgia drive through the hot, sticky panhandle on their way to the relief of the forgotten coast beaches. In the height of the season, Smiley fills his truck bed twice a month and plies his route, keeping folks well supplied with souvenir Florida tupelo honey.

Souvenirs are made in the honey house when extracting is done for the day. At his stainless-steel bottling tank, Smiley stands and dollops twelve ounces of honey into plastic bears like an expert soft-serve operator at the Dairy Queen. He fills hundreds before proceeding to one-pound bottles, then quart containers and gallon jugs. Paula sometimes helps package the comb honey, one of the more popular products. In the kitchen, she lays a large slab of honeycomb on a sheet of waxed paper and takes a knife to it as if cutting a tray of brownies. Each dripping waxy chunk is nestled into a glass jar, where it will be submerged in liquid honey. Paula smoothes blue-and-white or gold-and-brown Smiley Apiary labels on the filled bottles and loops a festive “Florida Honey” flag around every neck before warehousing it in the office or the extra bedroom. “I gotta build a bigger house to hold all this honey,” says Smiley, surveying the operation.

One morning before he starts his route, Smiley’s phone rings at about 6:30. It’s Curtis the barbecue man, in need of a delivery. Curtis is the proprietor of and cook at the Sea Breeze B-B-Que, a red-and-white trailer parked in an empty lot in downtown Wewa, across the street from Eddie’s Beauty Salon. On Thursdays, Fridays, and Saturdays year-round, Curtis sells mountainous piles of pork ribs dripping a secret-recipe honey sauce. This Friday morning, he’s worried that he won’t have enough honey to marinate and sauce his weekend ribs. Happily for Curtis and his clientele, Smiley adds the Sea Breeze to the top of the day’s itinerary.

Two hours later, he pulls up in front of the cheerful trailer. The screened and blackened smokehouse behind it wafts the delicious odor of sweet wood smoke and roasted pork throughout the intersection. Curtis emerges with a twenty-dollar bill and a wide smile. Smiley lowers the passenger side window and greets his customer with a friendly wave. From the backseat of the truck’s cab, a rumpled and sleepy George pulls up a plastic gallon jug of honey and hauls it over to Curtis in exchange for the bill. Everyone exchanges brief good mornings, and the first sale of the day is done.

Still smiling, Curtis heads back into the trailer to make his secret sauce. Smiley takes a sip of coffee from the ever-present mug and heads north up Route 71. Today, his sales and marketing uniform is a bright purple-and-green-striped polo shirt, black leather belt, and stiff new blue jeans. On his feet are shiny white running shoes and on his head a crisp new baseball cap, blue with “Alaska” in white embroidery. “I’ve always wanted to go to Alaska,” he says. “It’s the final frontier.” George is also wearing a baseball cap, pulled down over a mottled head of rusty golden hair with dark brown sideburns. He was in the middle of bleaching his cropped cut the night before when a family emergency came up and he had to abort the process. The oddly orange results are a source of amusement for both beekeepers throughout the day.

Teasing his nephew lovingly and mercilessly about his new look, Smiley drives through fields of dark green collards and cotton, where the last beige bolls of the season droop on faded stalks. The sky is a moody slate hanging low on the landscape and threatening rain. Thick airborne battalions of dragonflies escort the truck for moments at a time before darting away. Black-and-red lovebugs, joined in flying coitus, bump and smear against the windshield. In spite of the rich fertility he is driving through. Smiley complains about the weather. It has been rough and unpredictable this summer, with a cluster of hurricanes hovering off the coast. The abundance of precipitation and shortage of sun caused the nectar to come late and sparsely. Cold and rain also made the bees ornery and reclusive, so it was often difficult for him to get work done inside the hives. “I’d get all the way to the yard, get the smoker started, and then it’d start to rain, so I’d turn around and come home,” he sighs. The upside to his lament is that most local producers share it, so the crop will be smaller and prices a bit higher.

The second stop of the day is The Fruit Store in Alford, Florida. There is no sign of an actual town, just a wall-less emporium perched alone on the roadside. Signs leading up to the store and on the roof advertise LIVE GATORS, BONSAI TREES, GRAPEFRUITS, and FLORIDA T-SHIRTS. Inside, the air is heavy, moist, and still, smelling of the damp wood-chip floor and earthy boiled peanuts. Pickled eggs, relishes, grapefruits, Vidalia onions, shot glasses, and shell collections are displayed for sale under bright fluorescent lights, and wind chimes hang soundlessly from the ceiling. George goes to look at Larry, Curly, and Mo, the live gators, who are sixteen inches long and hiss at him fiercely from inside their chicken wire cage. Smiley asks a silent older man slumped in a porch swing if the boss is around. A grinning woman named Suzy appears, and Smiley says cheerfully, “Hey, boss. I thought you might need a little honey.”

Suzy eyes a shelf laden with jars of local strawberry-rhubarb jam, sorghum molasses, and Smiley’s honey and says, “We still got a pretty good bit, I’m afraid. Business is way off” They discuss the recent jump in gas prices, the faltering economy, and ways to increase tourism and sales. Suzy says the tourists are crazy for the forlorn-looking bonsai trees she has displayed in a corner, and for Smiley’s comb honey. “Mostly older folks,” Smiley says with a nod. “They remember comb from the old farm days. Younger ones don’t know what the heck it is.” He makes a mental note to start her with more of the comb next season. Suzy wants him to build a display for his honey on top of some old hive boxes. He makes a mental note of that too. If you ask Smiley what he does with all these notes, he points to his Alaska hat. “It’s all right up here.”

At the next stop, the salesclerk, an elderly man with a damp white T-shirt stretched over his ample belly, phones his boss as Smiley enters the store. “The honey man’s here,” he reports to the mouthpiece. “What do we need?” The boss orders two cases of twelve-ounce honey bears and two boxes of the one-pound jars, which George arranges on the fake grass-covered shelves next to some watermelon rind pickles. With a borrowed sticker gun, he taps the price onto each container, $3.50 and $4.50 respectively, while Smiley and the clerk swap business and fishing stories.

Later in the day, at the Piggly Wiggly supermarket in Chipley, Smiley strides into the store with his arms wide and announces to no one in particular that he has come with honey. “You guys still got most of that honey?” he asks a startled-looking clerk with a pink-and-red pig embroidered on his shirt breast. “I don’t know what we got,” the man says, looking confused as Smiley advances, passes him, and goes directly to aisle six, where the honey is. The shelf is in disarray, with bears fallen sickly on their sides, and gaping holes where rows of honey should be. “Looks like a hurricane got in here,” mutters Smiley as he begins to neaten and organize the shelves. “If there’s empty space on that shelf, I’m gonna fill it with my honey,” he announces as he makes way for his product. He sends his orange-haired deputy to the truck to get a supply of bears, which they mark at $2.89 each. The rows of Piggly Wiggly brand bears are priced at $2.79, and some other local producers are selling for as little as $2.50. “I’m only making a little bit off this packaged honey,” he complains. “It’s tough to compete with people selling for less than they should, less than store brand. They shouldn’t be doing that.”

At the end of a typical summer day on the route, they’ve made about twelve stops, delivered over eight hundred pounds of honey, and pocketed close to two thousand dollars, enough to pay some bills and buy some floor tiles and wall paint for the house. The produce markets took the bulk of Smiley’s load, while the supermarkets seemed a little slow. “Honey always seems to sell better in grocery stores in the wintertime, I wonder why that is?” muses Smiley as he stows the receipts in the console next to his coffee. George pulls his hat down over his brow and says, “More people makin’ biscuits.” Smiley nods slowly, impressed with his protégé.

On the way back to Wewa, they discuss hair, beekeeping, and business. Smiley is planning on expanding his operation to more than a thousand hives in the next year, and hiring George full-time to help him. “To be profitable, you need to have a lot of bees,” says Smiley. “If you got more than you can manage, you’re losing money. George here is going to help me manage.” He’s grooming his nephew for the production side of things, so he can devote more time to selling. “I could stand on the sidewalk and sell honey, it’s that easy,” boasts Smiley. “I just don’t have the time.”

Second to the beeyards, the sales route is the work he enjoys the most, interacting with customers and proudly, boisterously promoting his product. His enthusiasm on the route brings in almost fifteen thousand dollars a year, a tenth of his total sales. Web site business (at www.floridatupelohoney.com) is growing at about 20 percent annually and will soon account for another tenth of his income. Not quite as much fun, the bulk of his sales are made over the phone early or late in the day, when the work in the yards or on the route is done. He answers inquiries, follows leads, and calls his regular roster of bakeries, restaurants, supermarket chains, wholesalers, and distributors. After a quick report on how the honey is coming in, he can usually take or confirm an order. Customers vary from year to year, but call by call, barrel by barrel, and bear by bear, he sells out.

Tupelo sells easily, first, and for a premium price. People always want tupelo. If any gallberry or bakery-grade honey is not spoken for, he can send it to Dutch Gold, the packing company in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. If its price is right, he arranges for one of its trucks to come to Wewhitchka for a pickup. On the designated day, Smiley has the barrels stacked in the yard ready to go when a white eighteen-wheeler with pictures of honey bears and the Dutch Gold logo emblazoned on its side rumbles down Bozeman Circle. A few minutes later, Smiley has a receipt for his departed produce, and the truck is on its way again, picking up honey from other local beekeepers like a giant bee gathering nectar for the hive. When the belly of the truck is full, it begins the thousand-mile journey north to Lancaster.

Twenty hours later, the truck arrives in a landscape that is perhaps the cultural and geographic opposite of Wewahitchka. Yellow signs with black icons of a horse and buggy dot the roadside, as do pretzel shops and antique bazaars. Rolling green cornfields cradle old, orderly farms with stone barns and stenciled facades. Nestled into the heart of this Pennsylvania Dutch countryside is the Dutch Gold headquarters, a trim, modern white stucco building tucked behind an old farmhouse. Sixty million pounds of honey are processed here every year before being portioned into bears, bottles, and bulk containers for sale to food manufacturers, restaurants, warehouse clubs, and grocery stores.

Like so many honey businesses, Dutch Gold began with a few thousand bees, a backyard, and a curious beekeeper. Ralph Gamber, the founder, had a heart attack in his thirties, for which doctors suggested physical activity and a hobby. Gamber combined the two and in 1946 purchased three hives of bees for $27 at a farm sale. Over the next several years the hobby grew into a passion and then a business as the three hives multiplied into two hundred. With the help of his family Gamber harvested, bottled, and sold honey whenever he wasn’t working his full-time job at a food-packaging company. His children helped him make deliveries of pint and quart glass bottles until 1957, when their father designed a squeezable plastic bear to showcase and deliver the product. Winnie-the-Pooh was immensely popular then, in the world and at the Gamber home, and Ralph, a plastics enthusiast, thought it would be fun to incorporate the beloved icon into his sideline business. The bear was a huge hit and became the prototype for the legions lining pantry and supermarket shelves all over the world. By 1958 the container business had grown to such an extent that Gamber quit his job, abandoned his own hives, and became a full-time packager for other honey producers. His son Bill took over the booming business in the early nineties, and in 2002 passed the torch to his sister Nancy, who is now president of the company. Another sister, Marianne, runs Gamber Container, the enterprise that grew out of the original bear. Ralph died in 2001, but his widow Luella still comes in to headquarters every week to water the plants and visit with employees and friends.

Baby food jars, plastic honey bears, and dark prescription bottles arrive at Dutch Gold’s offices daily, sent by beekeepers auditioning their product. Every sample is run through the in-house lab, which resembles a brightly lit doctor’s office, stocked with gleaming equipment and jars of golden liquid samples. Flavor, moisture, and color are evaluated (drier and lighter are preferred), and the honey is screened for additives and chemicals. If the lab prognostics are good, tastes of honey are run across the discriminating and formidable tongue of Nancy Gamber, the principal buyer for the company. Passing this battery of tests, the producer earns a place on the roster of Dutch Gold suppliers and can send it honey by the truckload or the bucket.

When a truck arrives at the plant, barrels are unloaded and stacked in a warehouse with the acreage of a football field. Smiley’s barreled gallons join a towering, multicolored maze of honey from all over the world. Place of origin, flavor, moisture content, color, and quality grade (which is a combination of the latter three) are recorded in wax crayon on the outside of each barrel in the labyrinth of drums. When the processing of an order begins, a forklift driver fetches the components for each custom blend from this carefully marked liquid inventory. Like a vintner blending grape varietals or a coffee producer mixing beans, Dutch Gold combines flavor, dryness, and color to give the client the exact blend, body, and honey bouquet desired. It also packages a line of premium “monoflorals”—such as orange blossom, alfalfa, or sage—that, like fine wines from a particular grape, vineyard, and year, have not been blended at all.

Barrels for each batch are transported to the hot room, which is like a giant oven with garage doors, situated in the heart of the warehouse. The ingredients are parked here and their temperature slowly increased to 140 degrees. Heating resaturates any crystallization that might have occurred and makes the contents more manageably liquid for the blending and filtering ahead. Although the drums are sealed, the temperature sweats scent out of them, and the air around the heating room is thick and warm with sweet whiffs of honey. On days when the particularly fragrant orange blossom is heated, the warehouse smells like a humid citrus grove.

From the fragrant hot room, barrels of heated honey are transported to an elevated stainless-steel blending tub, where they are unsealed and upended two at a time. Molten honey cascades into a square metal vat below, where lazily churning paddles gently fold and mix the gallons of amber liquid. Blended batches are then piped next door to the filtering room, where their temperature is increased to the 180 degrees required to push them through a final series of cleansing filters. Not enough to cook or caramelize, the temperature renders the honey smooth and thin as water, and as easy to work with. As it exits the filters, the honey is cooled before being routed to holding tanks, where it rests at the temperature of a luxurious bath. From here, the warm river of honey is piped to the bottling room, where a fleet of bears and bottles awaits its cargo. The Dutch Gold plant is the honey version of Willy Wonka’s chocolate factory. A river of warm tawny sweetness flows through the cavernous place, plied by men and women in blue jumpsuits and white hair nets busily and cheerfully transforming golden tributaries into smiling plastic bears and shiny glass bottles.

About 40 percent of Dutch Gold honey is bottled or beared. Honey that is not packaged for retail sale is sold in bulk to food service companies and food manufacturers like Kraft and General Mills. For these customers, processed honey is shipped in “totes,” 3,200-pound plastic pillows of honey caged in metal bars. For even larger orders, 45,000 pounds are loaded, still warm, into a gleaming tanker truck before journeying to become Honey Nut Cheerios or Nabisco Honey Maid Graham Crackers. Some heated tankers drive from Dutch Gold to a portion-packing facility that divides the twenty tons of liquid into millions of little gifts from the hive, the plastic cups and squeezable half-ounce envelopes that sweeten the fare in restaurants and coffee shops.

Every bulk container that leaves the Dutch Gold warehouse has a locked red plastic security seal, which guarantees that the contents have been tested for additives and impurities. In the year 2001, trace amounts of the harmful antibiotic chloramphenicol were found in imported Chinese honey. Beekeepers there had used it to combat an epidemic of hive disease but failed to keep it from contaminating the product, which unfortunately made its way into the global supply. Chinese honey was temporarily banned, but nervous buyers demanded further guarantees of purity and safety, and the seals came widely into use. Security concerns escalated with revelations that containers of honey were being used to traffic money, drugs, and arms throughout the Middle East, where honey vendors are ubiquitous. Thick, fragrant, honorable honey had been put to a dishonorable new use: smuggling. A U.S. government official was quoted in The New York Times as saying, “The smell and consistency of the honey makes it easy to hide weapons and drugs in the shipments. Inspectors don’t want to inspect that product. It’s too messy.” When anthrax and tainted food supplies became a concern soon after September 11 of that year, security seals became regulation at Dutch Gold and other major dealers in the suddenly suspicious liquid. Even smaller suppliers like Smiley came under scrutiny. In 2003, complying with new bioterrorism regulations, he registered with the USDA, asserting the purity of his honey and his intentions. Backyard beekeepers making honey for their friends or the farm stand are thus far (and hopefully it will stay this way) unregulated and unregistered. They just give their solemn word that the product is innocent and delicious. And usually the honey speaks for itself.

From bears and bottles, totes and tankers, the National Honey Board estimates that Americans consume approximately 400 million pounds of honey each year, or about 1.3 pounds per person, twice as much as the 1,600 commercial beekeepers (defined as apiaries with over 300 hives) in this country can produce. Large distributors like Dutch Gold have to import almost a third of their annual supply from foreign producers, typically in winter, when American apiaries are dormant. Foreign honey, which is abundantly available and cheap, has turned into a year-round concern for beekeepers in the United States. Until the late 1990s, China and Argentina were the largest global exporters of honey (and two of Dutch Gold’s biggest suppliers). They exported honey for around thirty cents a pound, a third of what it cost Americans to produce the same amount. These prices devastated American beekeepers, forcing many of them out of the business. “I was getting offers for forty cents a pound,” recalls Smiley. “I had one hundred barrels of bakery honey sitting there, and I couldn’t sell it because I couldn’t compete with Chinese honey.”

While Smiley was getting offers of forty cents a pound, the American Beekeeping Federation filed a formal complaint, claiming that the cheap and often inferior foreign product being dumped on the market was deluging and destroying the American honey trade. As a result, the U.S. Commerce Department began imposing taxes of almost 200 percent on honey from China and Argentina. Antidumping tariffs reduced imports from those countries to a quarter of what they had been, and prices for American honey more than doubled. Smiley and the market recovered, but not without future foreign worries. Tariffs are temporary, and cheap competitors are always waiting to fill the American honey deficit. The president of the American Honey Producers Association has said, “We can’t produce enough honey for our own market, so we will always be an importing country. Beekeepers must understand that we are dealing with a world market and we are going to have to learn to live with it.”

Tupelo helps Smiley live with the foreign worry. It is always in demand, fetches consistently high prices, and is not threatened by foreign competitors, who don’t make it. It helps to live in Wewahitchka, tupelo Shangri-la. Thanks to the missionary with her seeds and the thief who stole and flung them, unique, plentiful acres of swampland and specialty nectar in his hometown are enough, if necessary, to take care of him for decades. “There are tupelo trees in some of the swamps so far in that no bee has ever touched them,” he marvels. Most of the swamps and trees are in state parks, so Smiley’s bees and future income are relatively well protected. “I can always sell tupelo,” he says. “Tupelo’s the thing that keeps me in business.”

Smiley’s list of business worries are: too much rain, too little rain, foreign honey, parasites, hive diseases, and pests. Smiley’s list of personal worries are: too much rain, too little rain, foreign honey, parasites, hive diseases, and pests. Small hive beetles (Aethinae tumidae) are of African origin but made their way somehow to Florida, where they were discovered in 1998. Since then, they’ve proliferated like weeds and are now found desecrating hives throughout the American South. They are about the size of a ladybug but black, ugly, hairier, and much faster. Established in a hive, the beetles consider the colony’s resources their own, consuming honey, wax, pollen, and larvae at a voracious, destructive rate. They are much less hygienically fastidious than bees and defecate in the honey, causing it to spoil and seep from the combs. Beekeepers know they have a bad beetle infestation when their honey smells and drips from the frame like rotten fruit juice.

Foulbrood is another common hive addiction, the result of bacteria that invade the hive and reduce the brood to a brown, stringy, useless soup. Two different strains of foulbrood, American and European, were the biggest problem in commercial beekeeping until foreign honey and mites came along in the early 1990s. First discovered in Indonesia in 1904, varroa mites made their way to the United States by 1986 by stowing away in worldwide shipments of bees. These ticklike parasites crawl into the bee brood cells, where they feast on the larvae and mate with abandon. When the adult bee emerges, if it is even able to do so, it is bedraggled host to several crippling mites. A colony can withstand a small mite invasion, but large marauding numbers of varroa will seriously compromise its strength and productivity. Another treacherous mite, the tracheal, sets up parasitic shop in the trachea of a worker bee, where it lays eggs and cripples the host’s ability to fly and feed. Beekeepers recognize a tracheal mite invasion when they see bees limping and crawling about the hive, unable to report to work. While foul-brood and beetles can be treated, mites have become increasingly resistant to chemotherapy; dozens of chemicals have been applied, with little long-term success. Researchers are experimenting with essential oils, screens, and mite-resistant bees with hope and some success, but 20,000 colonies in Florida, or 8 percent of the state’s commercial colony count, are still lost each year to the ravages of mites. If an effective defense is not found soon, the outlook for Smiley’s bees and his livelihood, tupelo and all, is bleak. “Mites are here to stay,” says Smiley. “They’re going to be a constant battle from here on out.”

With all of its irritations, uncertainties, and rewards, the honey business as Donald Smiley knows it has existed only since the late nineteenth century, when beekeeping innovations in Europe and the United States produced previously unimaginable surpluses. Until these advances, honey was primarily a domestic, limited, hive-to-mouth endeavor. Bees were kept close to the household, like a good laying hen or an exceptional milking cow, and their emissions were consumed within a few yards of production. In and around ancient Rome, residents embedded hives in the clay and stone fences surrounding their villas, and in India, North Africa, and Asia the mud walls of the houses themselves were studded with hives. Hollow log hives in central Africa and China were suspended beneath the eaves of thatch-roofed homes. As late as the 1850s in Europe, new houses were built with niches in the outside walls to accommodate skeps. Bees were an integral, intimate part of the household, their produce used to sweeten food and drink and illuminate the rooms within.

Discussing the best domestic arrangement for bees, Columella wrote in the first century that “It is expedient for the apiary to be under the master’s eye.” In ancient Greece and Rome, the master was often a male slave known as the melitore. Beekeeping was man’s work, and Columella advised that, to conserve their strength for the manly task, bee handlers abstain from sex for at least a day before going into the hive. Women were considered downright dangerous when it came to handling bees. Pliny the Elder warned that “If a menstruous woman do no more than touch a beehive, all the bees will be gone and never more come to it again.”

Later, the menstrual prohibitions seem to have faded away, and the task of caring for bees fell to the females of the house. John Levett wrote The Ordering of Bees in 1634, proclaiming in the foreword that “The greatest use of this book will be for the unlearned and country people, especially good women, who commonly in this country take most care and regard of this kind of commodity.” The author of The Complete Country Housewife declared the beekeeping particulars of his book “worthy of the attention of women of all ranks residing in the country.” While wild bees and honey hunting were manly pursuits, the tending of bees, chickens, cows, and the household herb garden were typically the dominion of women. Eva Crane writes, “In general, human gender roles in relation to bees and beekeeping conformed to gender roles in other activities.”

Eighteenth- and nineteenth-century houses in England were built with niches for beehives.

Skeps were part of the farm woman’s chore list from the first through the nineteenth centuries. The Dictionarium Domesticum, “A new and complete household dictionary” published in London in 1736, features illustrations of a woman going about her household tasks. She feeds chickens, churns butter, launders, cooks, bakes, and brews beer. In one tableau, the woman sits at her kitchen table and the open back door behind her reveals three busy backyard skeps, as important to her ménage as the butter or the beer. One hundred and fifty years later, bees and homemade honey were still the showpiece of an efficient housewife. A writer described a garden hive with glass collection jars “of such a size as to suit a family to breakfast, each of which may be daily introduced to the table fresh from the hive. A little honey on bread would save the use of butter on the occasion, and would be more wholesome; it is at the same time a luxury, that every family in possession of a garden, may command without expense.”

If they could, most households supported enough bees to supply the family with honey for the table and the mead vat, and wax for candles. A cottager might keep seven or eight hives, a larger household employed as many as ten or twenty, while grand estates had apiaries with dozens of hives. For most of their domestic history, bee domiciles outnumbered those of humans. The Domesday Book, compiled in England in 1086, inventoried everything of value in the king’s domain, including hives. There were 1,441 registered in rural East Anglia alone, at a time when there were fewer than ten people per square mile. William Lawson’s The Country Housewife’s Garden, published in England in 1618, offered beekeeping advice “with secrets very necessary for every housewife” and concluded, “if you have but forty stocks, shall yeeld you more commodity clearely than forty acres of good ground.”

From Dictionarium Domesticum, a housewife’s compendium and guide.

Illustration of a medieval Italian household and garden. Beehives are housed in domed niches in the wall directly in front of the house and some are also shown in the adjacent garden.

In the American colonies, the number of hives under the housewife’s command was similarly abundant. In New York, Daniel Denton noted in 1670, “You shall scarce see a house, but the south side is begirt with hives of bees, which increase after an incredible manner.” A hundred years later, a soldier in Pennsylvania observed that “every house has 7 or 8 hives of bees.” An estate for sale in nearby New Jersey included a house, barn, “valuable breeding mare, sheep, swine, several flocks of bees, household furniture, and farming utensils.”

Seven or eight hives (which, until the nineteenth century, were about half the size of today’s boxed hives) would have provided adequate honey for household baking, cooking, brewing, and sweetening. If there happened to be surpluses, they could be sold or exchanged for a variety of valuable goods and services, from bulls and bribes to brides and wine. The account books of the Egyptian pharoah Seti I indicate that one hundred pots of honey could be traded for an ass or a bull in the thirteenth century B.C. In the first century B.C., Diodorus of Sicily recorded honey being traded for protection from occupying Roman forces who were “lords of the cities for a considerable period and exacted tribute of the inhabitants in the form of resin, wax, and honey.”

A marriage contract in ancient Egypt contained a promise by the groom to deliver twelve jars of honey to his bride every year in exchange for her hand in marriage. In Africa, a single payment of twenty-five pots of honey was given to Masai fathers for matrimonial rights to their daughters. Strabo’s Geography of the first century describes Ligurian villagers who traded their surplus honey for olive oil and wine. In Strabo’s world, honey was often valuable enough to be traded equally with salt, that most precious currency.

Until the nineteenth century, in many parts of the world the rent could be paid in honey. Tax and rent laws were drafted throughout Europe specifying how much sticky tribute the landlord and sovereign could exact from each of his tenants. Eva Crane writes that in England in the eleventh century, a fine was imposed on a woman in Somerset, who “for six years has withheld her rent in honey and cash.” In some cases villages combined their honey resources and paid dues and rent to the local landowners and rulers. In South America, Mayan and Aztec warriors expected several hundred jars in honey annuities from their conquered foes, liquid rent for their own land. To sweeten his banquets (and his wallet), a greedy seventeenth-century Hungarian commissar depleted the honey supplies of the entire tiny town of Nagykoros, demanding 2,400 gallons in rent and taxes from the inhabitants. If only the IRS or MasterCard worked that way today.

When and where forest beekeeping was practiced, itinerant beekeepers often paid for the privilege by handing over dripping portions of the proceeds to the church and landowners. In parts of northern Europe, beekeepers tithed a portion of honey to neighboring farmers in exchange for letting bees forage on their property. When taking that honey home or to market, they would frequently have to pay a sweet liquid toll at the bridge or road into town.

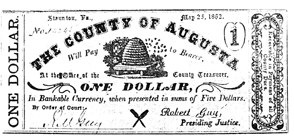

As providers of the coveted sweet, bees were themselves valuable commodities. Knowledgeable hunters could capture swarms in the wild and convert them to a steady profit stream. Aristophanes and other writers of antiquity mention a separate area in the marketplace where hives were sold. References to exact prices are scarce, but in 918 the worth of a new skep was the equivalent of two hundred eggs or twelve arrows. In the American colonies, damage claims after the War of Independence frequently inventoried bee losses, and one reported thirteen destroyed hives valued at forty-five dollars. Bees were so highly esteemed, and their honey so highly valued, that both were featured on local currencies.

One of many examples of currency graced with bees and hives.

In 1853, two hives of bees were sold for two hundred dollars to settle the estate of an American man who had been killed in a steamship explosion. A late-nineteenth-century photograph shows a bee market in Denmark, in which the smiling proprietors lounge next to a row of tied-up straw skeps, which they could sell for about seventy-five dollars each. Today, a three-pound starter package of bees with a queen, obtained from a dealer, costs around fifty dollars, and two assembled deep hive bodies with frames, bottom board, cover, and a super are another hundred and fifty. Tools to handle the bees—smoker, gloves, hive tool, and veil—will run to fifty or sixty dollars. Bee suits are optional (and extremely warm), but the security and confidence they provide the beginning beekeeper are definitely worth the sweat and the eighty-dollar price tag.

Though honey was typically a wild windfall or a limited domestic production, entrepreneurs have always procured surpluses for profit. While women usually tended the household hives, enterprising men established large apiaries to extract as much of the difficult yet lucrative yield as possible. Before 1865, however, manipulating “commercial” apiaries, unwieldy collections of logs, boxes, and baskets, was an arduous, sting-filled business. No matter how large and efficient the apiary or how expert its proprietor, yields were limited by knowledge and equipment to a few small, sticky harvests wrested from each hive each year. Langstroth’s revolutionary adaptation of bee space and Hruschka’s invention of the extractor in 1865 transformed honey from a domestic trickle or speculative sideline business into a thriving industrial flow. Other improvements helped. In 1869, not long after Langstroth’s revelation, the first transcontinental rail route was completed. With this and various other innovations in transport, massive numbers of bees and tons of their produce could be shipped quickly and cheaply to apiaries or to market. Additional advances in woodcutting machinery and plummeting lumber prices converted makeshift rural apiaries into neat rows of uniform wooden boxes that served as efficient modern honey factories.

Honey was now mass-produced via an assembly line of cheap, interchangeable, reusable parts, and surpluses and profits in beekeeping became abundant and reliable. By the end of the nineteenth century, machines and modernity surpassed centuries-old traditions and manual labors. As innovations multiplied, honey became a modern “manufactured” good that could be traded by the truckload and the ton instead of by the jar or bucket. Smiley’s vocation is thousands of years old, but the commercial honey business is just a century young.

Some of the biggest surpluses in the new industry have been realized in California. The state did not even have bees until the middle of the nineteenth century, but the climate and geography presented a rich vein of opportunity. With the excitement of miners in a gold rush, entrepreneurs imported bees to California for exploitation and riches. John S. Harbison of San Diego began receiving shipments of insects from the East by rail and in a few years was the premier honey producer in California. By 1876, the superstar beekeeper was able to ship a magnificently impressive and altogether unheard-of trainload of honey from his apiaries to New York City. In The History of American Beekeeping, Frank Chapman Pellett writes, “Harbison’s shipment of ten cars of honey to New York in 1876 created a sensation in the East. Beekeeping at that time was generally an insignificant side line and few beekeepers produced as much as a ton of honey in one year.”

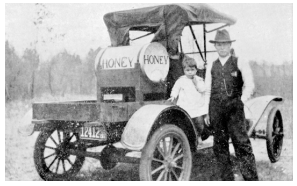

A southern beekeeper shows off his modern apiary in 1915.

A book published the next year claimed that Harbison had netted $25,000 on his 200,000-pound transcontinental shipment of honey, a considerable sum in 1876 and an unthinkable one just twenty years previously. With fame, wealth, and 3,500 hives, Harbison was one of the most successful apiarists to stake his claim in the California honey rush. According to the American Bee Journal, others were tapping into the western lode. “The crop of 1885 was about 1,250,000 pounds. The foreign export from San Francisco during the year was approximately 8,800 cases. The shipments east by rail were 360,000 pounds from San Francisco, and 910,000 pounds from Los Angeles.” Today, California still generates the most honey in America and, in 2003, produced thirty-two million pounds of honey worth $41 million.

In Florida, the race was a little slower. By 1872, when the California rush was in full swing, Florida was still a ferocious, roadless frontier where the bee business was conducted with considerable difficulty, mainly by boat. Pensacola (about an hour from Wewa) managed to support one of the first commercial apiaries in the area, although beekeepers had to move heavy boxes by ski. through swamps rife with alligators, snakes, and mosquitoes. It wasn’t easy working this landscape compared to the rolling green hillsides of California. In 1901, one of the pioneers in the area, M. W. Shepherd, described his precarious experiences in an article entitled “Beekeeping in West Florida, a Letter from a Land Flowing with Malaria and Honey.”

Twenty years later, a Canadian beekeeper named Morley Petit spent a year attempting his trade in Florida, after which he decided to hang up his veil and return home to the relative tameness and ease of Ontario.

Outside of Apalachicola districts this [the Lake Worth area] is said to be one of the best honey-producing districts of the state; but with all its uncertainties, strange pests, and the long active season, the surplus is probably no more than we get in a short sharp season and have done with it. This northern beekeeper is satisfied to raise his honey and make his money in good old Ontario, where he knows what to expect.

At about this same time, a beekeeper reported losing an entire boatload of bees to an unexpected squall in Pensacola Bay. Florida beekeeping was for swashbucklers, not the faint of heart. Census reports from 1910 indicate that the entire state of Florida eked out about 340,000 pounds of honey, close to what the city of San Francisco had shipped east twenty-five years previously. From its humble, hazardous beginnings in Pensacola and Wewahitchka, Florida, beekeeping (with the advent of citrus crops in the South) has grown in the last ninety years into the third largest producer of honey in the United States. Threats from malaria, alligators, and sudden squalls have lessened, but it’s still not the easiest place to produce honey, due to frosts, drought, beekeeper attrition, and pesticide and mite problems. Production in 2003 was down 27 percent from the year before, to fifteen million pounds worth $19 million.

Donald Smiley is part of a rich entrepreneurial tradition, but he’s not as rich as earlier entrepreneurs. In the time of Domesday or in the California glory days, seven hundred hives would have made him wealthy. He could have paid the rent and George in honey. In Egypt he could have boasted several bulls, and in Africa he might have been able to a.ord many wives. In the worrisome business of modern honey, he has one beloved wife and, weather permitting, does okay. “I’m probably not going to get rich doing this,” he says, thinking of the threat of foreign honey prices, and of the bees that need tending, the honey house that needs cleaning, product that needs selling, and a sticky pile of frames that require repairs. “It’s a lotta work and a lotta aggravation. But I love it.”

A man and a young boy in the honey business.