NINE

Medicine Ball

The Lord hath created medicines out of the earth.

Ecclesiasticus, 38:4

If the dew is warmed by the rays of the sun, not honey but drugs are produced, heavenly gifts for the eyes, for ulcers and the internal organs.

Pliny the Elder, Natural History

There proceedeth from their bellies a liquor of various color, wherein is medicine for man.

Qu’ran, 16:69 on bees

In winter, many people inaccurately suppose, bees and their keepers sleep a lot. In fact, in November and December Smiley is busily preparing for spring. His livestock is still up north, eagerly anticipating the same. There is not much to forage on anymore, so the bees feed on stored-up honey and look forward to the first awakening scents of spring. The cotton fields near where the bees are bivouacked are now acres of dark brown, prickly stalks, naked and withered except for a few stray wisps of bedraggled cotton hanging like toilet paper from trees on the day after Halloween. In lots where the plants have been trimmed to the ground, stray cotton collects in dirty tapered drifts like melting snow.

It rarely snows in the panhandle (Smiley can remember three storms in his lifetime), but it regularly gets cold enough to freeze above-ground pipes and send bees into their winter formation. They cluster loosely and casually all year, but when the temperature drops below fifty-seven degrees, they contract into a basketball-sized scrum within the hive. This tight cluster is the winter furnace for the colony, fueled by honey and the intentional shivering of the bees as they contract their wing muscles. On the surface of the ball, workers create a thick, insulating shell of live bodies that hovers at around forty-five degrees no matter how low the temperature drops. The bees forming the crust are inert, conserving their energy and accepting the heat generated by the bees within. The interior grows progressively warmer and busier toward the core, where the queen goes about her reproductive business at a constant balmy temperature of around ninety-three degrees (even if there is snow drifted on top of her hive). During long cold periods, the bee ball with its royal core moves slowly around the nest, consuming the food it has stored. Bees don’t sleep or hibernate in winter, but, like many of us, they become generally lethargic and subdued, resting and preparing themselves for the warm rigors of spring.

In the coldest months, when nectar and hive activity are at an annual low, the queen herself usually takes a holiday. She doesn’t actually get to leave the workplace but does quit her laying job for about four weeks, usually in December. In January, refreshed, she goes back to work building up the hive population for spring. Worker bees also get a reprieve of sorts in winter; they are spared the mileage and wear of forage and live up to four times longer than their summer counterparts. The monarch and her elderly crew all slow down in the cold. Their groggy mandate is to eat, stay warm, keep queen and brood comfortable, and be prepared to charge out of the hive as soon as they sense the return of nectar.

In winter, while the bees are chilling, the first nectar flows of the Florida panhandle are only a couple of months away, and Smiley has to repair old hives and build new ones to catch them. A beekeeper’s winter looks a lot like a carpenter’s. The shed and yard next to Smiley’s honey house look like an outdoor furniture factory, with drifts of sawdust on the hard-packed ground beneath an assortment of tools, paint cans, table saws, and stacks of raw pine lumber. Rolling up his long sleeves and taking a swig of coffee, Smiley flips on a saw, grabs a long board, and goes to work. Over the course of the next several weeks, between drive-bys, he and George will transform the pile of lumber into 400 new hives to house 400 new colonies of bees in the spring.

There are many ways to get new bee colonies. Swarms can be trapped in the wild (although those numbers are dwindling), ordered from a supplier, or raised in the apiary. Experienced beekeepers have many different methods of making new livestock. All involve taking brood and food frames from existing hives, borrowing some workers to service them, and adding a new queen they’ve purchased or raised to mother and multiply them. It’s like taking bread dough from different loaves, adding some royal yeast, and creating an additional bustling loaf of bees. This beekeeping baking is done all the time, but most often in early spring, so that the new colonies will be kneaded and risen, ready to chase nectar by April and May. Smiley makes boxes all winter to house the new spring loaves, called splits or increases. The boxes he builds this winter, and the bees he’ll raise in them in the spring, will increase his annual honey production by about 50,000 pounds if all goes well.

While Smiley cuts pine board into box-size lengths and uses another saw to incise carrying handles deep into them, George is nearby, at work replacing splintery wooden frame parts that were bitten and chewed in the metal teeth of the uncapping machine. In the fall construction work, there are often minor beekeeping injuries. “Me and George are always getting banged up around here,” Smiley says, inspecting a bloody scratch on his arm. Fortunately, he has a limitless supply of one of the world’s great healers at hand and can smooth honey onto most of his minor scrapes. For as long as humans have been acquainted with bees, they have been getting medicine from them in the form of honey, propolis, pollen, and even venom. The hive is an ancient apothecary, loaded with convenient, economical, and powerful remedies.

The antibacterial and moisturizing qualities that made honey invaluable in the kitchen also made it a staple of the doctor’s bag. Its hydrogen peroxide, which helped preserve meats and fruit, was also an effective cleansing treatment for wounds, aided by the osmotic thirst of honey’s sugars. When applied to an infection, the absorbent sugars in honey act as healing sponges, draining intruding organisms of their liquid essence and causing them to shrivel and die. At the same time, the sugars nourish healthy cells and encourage white blood cells in their healing battles. Antioxidants, amino acids, and vitamins in the natural ointment reduce inflammation and speed the growth of healthy tissue. A golden smear of honey across a splinter-pricked thumb or scratched arm cleans the wound and promotes healing while providing a moist protective barrier. As he saws and scrapes, Smiley often employs the world’s first self-adhering Band-Aid, complete with its own vitamin-rich antibacterial ointment.

Smiley applies his product to cuts and burns and uses it in a sore throat gargle. Using his mother’s recipe, he combines about two tablespoons of honey, an eighth of a teaspoon of alum (an astringent he gets from the grocery store), and a teaspoon of lemon juice in a pint jar. “I fill that jar with water and keep it in the fridge and gargle with it. Boy, that’ll knock the sore throat right outta you,” he says. “Make your mouth feel like you’re chewing on a cotton ball, but it works. I guaran-damn-tee it.”

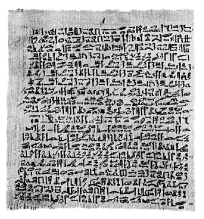

Ancient Egyptians had a similar guaran-damn-tee’d recipe for sore throats. The oldest known intact book of medicine is the Papyrus Ebers (named after the German Egyptologist who acquired it in 1873), a fifteenth-century B.C. collection of more than 800 medical problems, diagnoses, and prescriptive recipes, more than half of which employ honey. Used alone or combined with animal, vegetable, and mineral compounds, the produce of the hive was used to treat everything from head wounds to human bites. For an aching throat, the Papyrus Ebers suggested a bit of goose grease combined with honey, incense, caraway seed, and some water, rolled into a ball, and chewed nine times. To heal an eye, “when something evil has happened to it,” the papyrus calls for a human brain and some honey. “Divide it in halves. To one half add Honey and anoint the eye therewith in the evening. Dry the other half, crush, powder, and anoint the eye therewith in the morning.” To induce an abortion, or “for loosening a child in the belly of a woman, one part fresh beans and one part honey, pressed together and drunk for one day.”

Each of these remedies would have been administered by a priest, who would strengthen its effect by chanting spells and incantations as he applied his honeyed potions. Illnesses at this time were thought to be the manifest displeasure of the gods, so remedies had to both relieve symptoms and placate the deities. Physicians were priests, sorcerers, and shamans combined, and honey, with its supernatural support, was a persuasive, popular healing staple.

Classical Greece inherited much of its healing herbal repertoire from the Egyptians, the acknowledged experts. In the Odyssey, Egypt in 800 B.C. is described as the place where “There grow all sorts of herbs, some good to put into the mixing-bowl, and others poisonous. Moreover, every one in the whole country is a skilled physician.” Greeks celebrated and expanded the Egyptian pharmacopoeia, though they were less enthusiastic about the spells and sorcery. In classical Greece, illness was not a vengeful act of God but a bodily imbalance that could be remedied with knowledge. By the fourth century B.C. the Greek physician Hippocrates and his followers had catalogued the ailments of the world, enumerating over three hundred drugs and their uses while pointedly omitting magic and superstition. For the treatment of hemorrhoids, for example, Hippocrates offers advice free of hocus-pocus and full of brutal, honeyed practicality.

Have the person lie on his back, and place a pillow beneath the loins. Force the anus out as far as possible with your fingers; heat the irons red-hot, and burn until you so dry the hemorrhoids out that you do not need to anoint: burn them off completely, leaving nothing uncauterized. Let the assistants hold the patient down by his head and arms while he is being cauterized so that he does not move….After you have applied the cautery, boil lentils and chick peas in water, pound them smooth, and apply this as a plaster for five or six days. On the seventh day, cut a soft sponge as thin as possible, place a piece of fine thin linen cloth equal in size to the sponge on top of it, and smear with honey [to make a poultice for the wounds].

Oozing ulcers seem to have been a prevalent problem in classical Greece. Hippocrates suggests that a sufferer “place lumps of very dry salt in a small copper vessel or a new pottery one, and add to the salt the finest honey, estimating the amount to be twice that of the salt. Then place the little pot on the coals, and leave it there until everything is completely burnt; then sponge the lesion off clean, and attach the application with a bandage.” Honey was the enlightened doctor’s versatile salve and tonic, used throughout the Hippocratic medical repertoire.

Hot irons and salt rubs could be avoided altogether (and this sounds like a good idea) if one lived a balanced life with a healthy diet, a bit of exercise, and a lot of honey. “Wine and Honey are held to be the best things for human beings,” Hippocrates wrote, “so long as they are administered appropriately and with moderation to both the well and the sick in accordance with their constitution; they are beneficial both alone and mixed.” It is said that the philosopher Pythagoras ate a strict vegetarian diet rich in honey and lived to the age of 100. Democritus, the renowned physicist, is also believed to have lived for almost a century, perhaps double or triple the average of the day, and divulged his secret as “oil externally and honey internally.”

Chinese medical use of honey was similarly practical, reverential, and broad. Shen Nong’s Book of Herbs from the second century B.C. extolled honey as a top-grade healer that could be taken for specific ailments and general good health. “It helps to kill pain and relieves internal heat and fever and is useful to many diseases. It may be mixed with many herbal medicines. If taken regularly, one’s memory may be improved, good health ensues, and one may feel neither too hungry nor decrepit.” The first ayurvedic doctors in India admired and employed honey in many of the same ways. In Mecca, the prophet Mohammed said, “Honey is a remedy for every illness.”

Three centuries after Shen Nong’s Book of Herbs, Pliny the Elder was at work compiling his massive thirty-seven-volume Natural History. He devoted fourteen of the volumes to cataloging plants, animals, minerals, and their medical uses, concluding that “There is nothing which cannot be achieved by the power of plants.” He might have added, “and honey,” as almost every one of the healing plants he described was paired with honey to effect various cures. Olive leaves pounded with honey could be used for “suppurations and superficial abscesses.” Almonds and pomegranate rind combined with honey “is good for the ears, kills the worms in them, and clears away hardness of hearing, vague noises and singing, incidentally relieving headaches and pains in the eyes.”

Sometimes, the power of plants was mixed right into the honey cure. Bees, in their divine wisdom, are strongly attracted to medicinal plants. Like flying herbalists or perfumers, they select and mix plant essences into their healing food. Pliny was aware of these essences and suggested different honeys for particular ailments. Attic honey, for example, from the thyme-blanketed hillsides of Athens, was thought superior for treating eye problems, infused with medicinal properties whose fame was widespread. In the Papyrus of Zenon, Dromon writes to Zenon: “Order one of your people to buy me a kotyle of Attic honey, for I need it for my eyes, by command of God.” Pliny’s contemporary, the great physician Dioscorides, noted that “Honey made in Sardinia is bitter, because of the food of worme-woode, yet it is good for sunne burnings and spots on the face, being anointed on.”

Dioscorides compiled De Materia Medica, a colossal five-volume book of medicine, while traveling the world as a doctor in Nero’s army. Throughout his journeys, he assembled the first comprehensive universal medical dictionary, listing over 1,000 drugs and their uses. The first of several enthusiastic pages on honey or “mel” begins:

Attick honey is the best and of this that which is called Mymettium, afterward that of the cyclad islands and that which comes from Sicilie, called Siblium. That is best liked of, that is sweetest, and sharpe, of a fragrant smell, of a pale yellow, not liquid, but glutinous and firme when in ye drawing doth leap back to ye finger. It hath an abstersive faculty, opening the pores, drawing out of the humors, whence being infused it is good for all rotten and hollow ulcers. Being boyled and applied it conglutinates bodies that stand asunder one from the other, and being good with liquid Allum and so applied as also the noyse in the eares and ye paines, being dropt in luke-warme with sal fossils beaten small and being anointed on, it kills lice and nitts. It also cleanseth the things that darken the pupillae oculi. And it doth also heale inflammations about the throate, and about ye tonsillae, and the squinsies, being either anointed on or gargerized; it doth also move urine and cures coughs and such as are bitten of serpents.

In addition to having its own entry, Mel is found throughout De Materia Medica under uses for various herbs. Of rue (a mountain herb), for example, Dioscorides asserts: “Ye juice being anointed on with ye juice of fennel and honey it helps ye dullness of sight.” (This is first-century medicine; please do not try at home.) Of lentils, that Hippocratic hemorrhoidal favorite, he writes, “with honey doth conglutinate the hollowness of sores, it breaks scabs of ulcers round about, and cleanses the ulcers.” Of alum roots (Donald Smiley’s sore throat remedy), “They close moist gums, and with vinegar or honey they strengthen wagging teeth.” With its comprehensive nature, clinical calm, and abundance of honey, Dioscorides’s De Materia Medica was the Physician’s Desk Reference of its day and the standard medical reference for the next seventeen centuries. Even today, while there are better treatments for snake bite and wagging teeth, many of Dioscorides’s honeyed remedies, such as gargerizing the tonsillae (gargling for a sore throat and tonsils) or anointing it on sores, help soothe and heal.

Animal, mineral, and herbal cures were translated back and forth between cultures and languages throughout the Middle Ages, but their classical content did not change. Even the great tenth- and eleventh-century physicians of Arabia borrowed from Dioscorides, as did the healers in Europe. Hildegard of Bingen, a twelfth-century German abbess renowned for her healing abilities, compiled Physica, a book of remedies typical of the day and obviously indebted to Dioscorides. For a person who has “turbulent eyes,” she writes, “so that at times there is a cloud which fogs them in some way, should take the sap of rue, and twice as much pure liquid honey, and mix them with good clear wine. He should put a crumb of whole wheat bread in it, and tie it over his eyes, at night, with a cloth.”

Herbal remedies were honey-sweetened heirlooms, handed down from generation to generation, always tracing their ancestry back to Ebers and Dioscorides. A colic remedy from The Queen’s Closet Opened of 1655 is not much different from the curing plasters of ancient Egypt or Rome. A Persian manual of medicine from 1685 lists an alphabet of diseases, from apoplexy to worms, and then offers a range of honeyed herbal treatments. If one’s ailment was impotence, for example, there were a couple of sweet variations on Viagra. “For erection: the seed of the herb-rocket, and pepper with honey morning and night take as much as you can take up to two fingers. But if a man be grown old, and have a loose and hanging member, he shall do this. Of seed of rocket, cumin, pepper, and seed of purslane, being bruised and made up with honey, let him take it morning and evening. It is incomparable.”

During the nineteenth century, honey was still utilized in remedies as it had been in the temples of Egypt and the apothecaries of Greece and Rome. Lorenzo Langstroth reported that

…in Denmark and Hanover, the treatment of Chlorosis [anemia], by honey, is popular. The pale girls of the cities are sent to the country, to take exercise and eat honey…. Honey, mixed with flour, is used to cover boils, bruises, burns etc. It keeps them from contact with the air, and helps the healing. Beverages, sweetened with honey, will cure sore throat, coughs, and will stop the development of diphtheria.

Doctor John Monroe of Vermont wrote The American Botanist and Family Physician in 1824. Echoing the enthusiasm and breadth of Dioscorides, he summarizes honey as “detergent, expectorant, emollient, demulcent, and highly purgative. It powerfully promotes expectoration; deterges and resolves rigidities…temperates that acrimony of the humors; helps coughs, asthmas, disorders of the kidneys, and urinary passages, and the sore mouth and throat. It closes ulcers, purges moderately, and resists putrefaction.”

Today honey is still widely used as an emollient, detergent, and reliable resistor of putrefaction. This is especially so in poorer countries, where it is cheap and where traditional herbal healing is practiced. Kolawole Komolafe wrote recently in Medicinal Values of Honey in Nigeria that most of the 200,000 healers in his country include honey in their preparations. In his 1990 book on health sciences in India, B. L. Raina wrote, “In all parts of India, the elderly ladies in the house or neighborhood often suggest treatment of common complaints. The articles suggested for treatment are found in the kitchen, such as honey and ginger, or in the backyard, or readily available with the grocer, or growing wild in the neighborhood.”

In “progressive” Western medicine, honey and other folk remedies fell out of favor during World War II as ambitious chemical drugs were developed. Lately, however, a medical honey renaissance has occurred as trials on animals and humans have validated the natural ointment. The journal Burns published a report in 1998 comparing honey treatment on burn victims to the standard of silver sulfadiazine. Of the 52 patients doctored with the natural salve, 87 percent healed within 15 days, compared to 10 percent of those soothed with chemicals. Honey recipients also experienced less pain, wound leakage, and scarring. Peter Molan, a doctor who codirects the honey research unit at Waikato University in New Zealand, has said, “Randomized trials have shown that honey is more effective in controlling infection in burns than silver sulphadiazine, the antibacterial ointment most widely used on burns in hospitals…. At present, people are turning to honey when nothing else works. But there are very good grounds for using honey as a therapeutic agent of first choice.” Topical honey treatment is not a first choice just for burns. Doctors in India who applied honey and taped the outer incisions after a caesarean section found it to be more effective and less painful for the patient than chemical dressings and sutures. German doctors used a mixture of honey and anesthetic to treat herpes zoster, or shingles, successfully. There are many, many examples from all over the world of the ancient healer soothing a variety of modern wounds and complaints.

Taken internally, honey has been found to kill Heliobacter pylori, the bacterium that causes ulcers, and is even making inroads on staphylococcus infections. In Honey, Mud, Maggots, and Other Medical Marvels: The Science Behind Folk Remedies and Old Wives’ Tales, Robert and Michèle Root-Bernstein enumerate the ways in which honey has recently helped heal both external and internal ailments. The Root-Bernsteins report that a bacteriologist tested the antibacterial activity of honey on typhoid, pneumococci, streptococci, dysentery, and other bacteria. “Without exception, all were killed within a few days of exposure to honey, and most within a few hours.”

Even present-day eyes have resorted to the remedies of Ebers and Dioscorides. Herb Spencer, the president of the Southwest Missouri Beekeepers Association, wrote to the American Bee Journal in April 2004 to describe the benefits of dabbing honey into his ailing eyes. Experiencing blurred vision and excessive tearing when he drove at night, and familiar with the healing history of honey, he

started putting raw honey in my eye every night. I did this by putting a drop of honey on my forefinger, and pulled my right lower eyelid down and dabbed the honey on my lower eyelid which closed immediately to begin distribution all around my eyeball. It does burn a little bit, but only for a couple minutes. In about three days, I could discern a big improvement, so I started putting it in both eyes … now I can see to drive at night.

After reading Herb Spencer’s testimonial I imitated its author, and the ancients, and tucked a drop of raw honey behind each lower lid when my eyes were feeling dry and fatigued, or, in the words of Ebers, when “something bad had happened” to them. (I also swigged an oral dose for good measure.) Spencer was right about the slight burning sensation and also the rejuvenating effects. As the great Columella said of honey, “You will be amazed.”

Honey helped my tired eyes and Spencer’s night blindness. Some doctors and researchers hope it will tackle some blind spots in areas of conventional medicine. The authors of “Honey—A Remedy Rediscovered” wrote in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine that “The therapeutic potential of uncontaminated, pure honey is grossly underutilized. It is widely available in most communities, and although the mechanism of action of several of its properties remains obscure and needs further investigation, the time has now come for conventional medicine to lift the blinds off this ‘traditional remedy’ and give it its due recognition.” Hippocrates, Dioscorides and other ancient physicians would surely have agreed.

A honeyed portion of the Papyrus Ebers.

Honey was as popular in the boudoir as it was in the kitchens and pharmacies of history. It is a humectant, which means it promotes the retention of water, so a thin veneer smoothed onto the face or washed onto the body attracts and holds moisture on the skin. Nourishing and antibacterial, the bees’ emollient brew has been used to cleanse, soften, and brighten faces from Nefertiti’s day to our own. The Papyrus Ebers devotes quite a lot of hieroglyphs to cosmetics and honey, suggesting potions for everything from removing spots on the face to growing lustrous hair on the head. “To make the face smooth, take water from the qebu-plant, meal of alabaster, fresh abt-grain, Mix in honey, and anoint the face therewith.” Or, “to remedy and beautify the skin, use meal of alabaster, meal of natron, sea-salt, honey, and anoint the body therewith.”

Cleopatra, a descendant of Nefertiti, and another notorious beauty, is said to have compiled a book of grooming tips, dedicating many pages to the use of honey. As a proper Egyptian queen, she had great interest in hygiene and scent. Perfuming the body with unguents and oils and thoroughly fumigating one’s person and chambers with fragrant incense were part of the daily beauty regimen. The Ebers, if she consulted it, had many recipes for such fumigants: “In order to make pleasant the smell of the house or of the clothes, crush, grind and combine myrrh, elderberries, cypress, Resin-of-Aloes, inekuun grain, mastick, and styrax. Put into honey, cook, mix and form into little balls and fumigate with them. It is also worth while to make mouth-pills out of them to make the smell of the mouth agreeable.”

Like Cleopatra herself, the Egyptian obsession with fragrance eventually made its way to Rome. Citizens there were soon just as obsessed with banishing wrinkles and smelling good as the Egyptians. Pliny the Elder describes a popular, expensive first-century scent called metopium, made with almond-oil from Egypt, to which were added green olive oil, cardamom, rush juice, reed juice, honey, wine, myrrh, balsam seed, and the aromatic resins galbanum and terebinth. These ingredients were exotic and costly, but seduction was worth the expense. “When a girl wearing the best metopium passes, she attracts the attention even of those who should be otherwise occupied.”

The poet Ovid, who lived from 43 B.C. to 18 A.D. (during or close to the metopium craze), wrote The Art of Beauty, describing the vanities of the day and offering a few lyrical grooming tips:

Learn now in what manner, when sleep has let go your tender limbs, your faces can shine bright and fair. Strip from its covering of chaff the barley which Libyan husbandmen have sent in ships. Let an equal measure of vetch be moistened in ten eggs, but let the skimmed barley weigh two pounds. When this has dried in the blowing breezes, bid the slow she-ass break it on the rough mill-stone: grind therewith too the first horns that fall from a nimble stag. And now when it is mixed with the dusty grain, sift it all straightaway in hollow sieves. Add twelve narcissus bulbs without their skins, and let a strenuous hand pound them on pure marble. Let gum and tuscan seed weigh a sixth part of a pound, and let nine times as much honey go to that. Whoever shall treat her face with such a prescription will shine smoother than her own mirror.

Another poetic potion, claims Ovid, “will clear freckles from the face in a trice, of this about three ounces may suffice, But e’er you use it, rob the labouring bee, to mix the mass and make the parts agree.” These were popular antiaging formulas. Pliny reports on a famously vain woman, Polla, who spent her sixtieth birthday immersed in a version of Ovid’s recipe, a “poultice of honey and wine lees with finely ground narcissus bulbs.”

Poppea, the second wife of emperor Nero, lived a few decades after Ovid and surely was a fan of the honey-narcissus formula. Famously beautiful, conceited, and indulgent, she boasted of having a hundred slaves to keep her thus. Her staff bathed her body in asses’ milk and honey twice a day to preserve the luster of her skin and applied a daily facial mask of honey and herbs, washed off also with asses’ milk. (This softening, moisturizing bath can presumably be achieved with cow’s milk if asses are unavailable.) These efforts, though undoubtedly successful, were not enough to prevent her husband from tiring of her and eventually murdering her. Honey does not cure everything.

Fashionable men and women continued to primp, polish, and perfume themselves with honey for the next two thousand years. In the seventeenth century, The Queen’s Closet Opened, published in England, offered household and cosmetic hints for ladies, addressing concerns and using ingredients that had not changed from the times of Nefertiti or Poppea. “A water of flowers good for the complexion of ladies. Take the flowers of elder, a flower-de-luce, mallows and beans, with the pulp of melon, honey, and the white of eggs, and let all be distilled … this water is very effectual to take away wrinkles in the face.” In a French beauty manual of the mideighteenth century, honey was involved in a kind of moisturizing blush stain. “To make a water that tinges the cheeks a beautiful pink: take a quart of white wine vinegar, six ounces of honey, three ounces isinglass; two ounces of bruised nutmegs. Distill with a gentle fire, and add to the distilled water a small quantity of Red Sanders in order to color it.” A hundred years later, honey was still a staple for the European beauty. Toilet Table Talk, which debuted in 1850 in London, advised ladies to strain and heat a pound of honey, add a pound of white bitter paste, then two pounds of oil of bitter almonds and five egg yolks in alternate portions. Users were instructed to apply the results daily to keep the face fresh, soft, and beautiful.

With the industrialization of the late nineteenth century (and of course the rise of sugar and its sad eclipse of the beehive), beauty and personal care products were no longer made in the home with ingredients gathered from the kitchen, garden, and beehive. Beauty and hygiene increasingly sought rescue in modern science and chemistry, and grooming supplies migrated to the drug or department store. But as in holistic medicine, old-fashioned, natural, and honeyed folk remedies have lately enjoyed a renaissance in beauty. Ingredient lists on many popular products read like an ancient herbal, the contents so natural, effective, and dripping with honey and beeswax that they might have been concocted by Cleopatra herself.

Beeswax is one of the most frequently used ingredients in cosmetics new and old. When wax is emulsified, its plasticity allows it to be spread thinly on the face and body, holding scent, color, moisture, and herbal beautifiers firmly in place like a delicate scaffold or glove. Egyptians used beeswax as a foundation for many creams, including one in Ebers that calls for beeswax crushed with incense, fresh olive oil, cypress oil, and fresh milk, then applied for six days to “drive away wrinkles from the face.”

Beeswax was also important in Nile Valley hair care, where heads were shaved bare for aesthetic, hygienic, and heat reasons, making wigs a necessity for the pageantry of the temple. Wax was used to sculpt and hold these extravagant fake hairdos in place. Elaborate wigs found in tombs of the late Egyptian dynasties were made of date-palm fiber and grass styled with beeswax. Until the nineteenth century, all over the world, wigs and mustaches were curled, twirled, and set with beeswax. For most of humanity, desirable hairs, such as brows and lashes, could be polished, a8xed, and embellished with beeswax, while unwanted ones could be removed with it.

Though it is an ancient art and inquiry, the term “apitherapy” has been employed for the past few decades or so to describe the therapeutic use of hive products. Besides honey and wax, four other bee-related materials have traditionally been applied, or are just beginning to be used, in medicine and cosmetics: pollen, propolis, royal jelly, and bee venom. These compounds and their benefits are still incompletely understood by science, but as the secrets of the bee continue to be revealed, it is clear that the hive has even more magic and beauty in store.

Plant pollen collected by bees has always enjoyed a reputation as a health food. The Egyptians aptly called it “life-giving dust,” believing that it was delivered to the hive from the life-giving gods above. Aristotle described the bee as it “carries wax and bee bread round its legs.” Bee-collected pollen was often called bee bread, perhaps with the idea that the insect had fetched the loaf from some celestial bakery. The little loaves were more nourishing than bread; they were dense pellets of protein, packed by the bees and garnished with honey. Since most ancient honey was eaten in the comb or crudely strained from it, honey was infused with this life-giving substance.

Stored pollen was also scooped out of the comb, an orange waxy mash of proteins, vitamins, and sugar that could be eaten as a quick energy food. Olympic athletes were said to feast on this ambrosia before the games, and Mayans spread it on tortillas for energy, travel food, and religious ceremonies. The twelfth-century Jewish philosopher Maimonides reportedly used pollen in honey as a sedative and an antiseptic for wounds. His contemporaries in Arabia and China used it as an aphrodisiac and diuretic.

Historically, people got their pollen from the hive, sloppily mixed with honey and wax. In China, special nets were devised and dragged across lakes to harness the pollen fallen on the surface. This valuable commodity was eaten plain, added to other foods and medicinal teas, or combined with honey to make nutritious cakes in times of scarce food supply. In The World History of Beekeeping and Honey Hunting, Eva Crane relates the story of an injured U.S. Army officer in China in the 1940s. Locals fed him a mixture of fruit and wind-blown tree pollen and placed a gooey salve of honey and pollen on his injured feet. “The people stored the dry pollen in clay jars and used it as medicine, antiseptic, and food,” writes Crane. “They also kneaded honey and pollen together into flat strips which were dried … and eaten daily on hunting trips and during the monsoon season.”

Since the 1940s, pollen screens have been used to scrape some of the colorful load of protein from the bees’ hind legs as they wriggle into the hive. The harvested miniature loaves are sold in health food stores as a diet supplement, an invigorating source of vegetarian protein. Components vary according to plant sources, but the average pound of pollen has about 100 grams of protein, the same as a pound of sirloin beef. That same amount of pollen has 1,000 milligrams of calcium and 159 of vitamin C, while a steak has 46 and zero milligrams respectively. Pollen contains twice as much potassium as steak and has large multiples more of vitamin A, thiamin, riboflavin, and niacin. It can be eaten plain or as a dietary supplement, or mixed into facial masks and creams as a way to pack these nutrients onto the skin.

In recent years, pollen has proven itself to be more than a food and facial supplement. Plant allergy sufferers believe that ingesting local pollen desensitizes them to the allergens the same way that shots do (the same goes for local honey, which contains trace amounts of the allergens). Bee-collected pollen is also eaten by men who swear that it increases their libido and sexual performance, an as-yet-unproven claim. Proponents have alleged that the bee’s protein capsules can cure everything from obesity to cancer and infertility, though scientists have not found any proof to back these assertions.

A couple of years ago, I conducted an unplanned, very unscientific experiment on the effects of eating bee-collected pollen. I was interviewing a beekeeper in Georgia who sold it from a roadside stand to dieters, athletes from the local university, and men seeking a libido boost. All of his customers, he said, swore by its performance-enhancing abilities. When my visit was over, I grabbed a one-pound sample jar to take home with me and began the long drive back to the Savannah airport. As usual, I was short on time and hungry, so I started gulping pollen as if I were eating Grape Nuts from the box, in big, dry, crunchy, chewy mouthfuls. After eating about a half a cup, I didn’t feel hungry anymore. I did feel both elated and sick, stoned and manic, as if I had had about twenty cups of Smiley’s coffee. My pupils in the rearview mirror seemed huge, and my hands on the wheel were shaking. Forced to pull into a truck stop to get a drink and calm down, I was sure that two policemen, parked there on a coffee break, eyed me with suspicion. Guzzling water (and driving fast), it took me a couple of hours to metabolize my pollen excess. Now I eat an energizing spoonful in the morning or sprinkle it sparingly on toast, salads, or yogurt. It probably isn’t a cure for cancer, but it is potent stuff.

By the first century in Rome, hive watchers had noticed a sticky substance that the bees used to patch, mend, and strengthen their homes. Someone at around this time named it pro-polis, meaning “before the city,” having observed that bees used it to strengthen and protect their fortresses. Pliny accurately noted that propolis “is obtained from the milder gum of vines and poplars …with it all approaches of cold or damage are blocked.” The fragrant cement that the bees collect from the saps and resins of trees is at first sticky and malleable, and is industriously lacquered throughout the interior before hardening into a brittle rust-colored ta.y that caulks, weatherproofs, and strengthens the domicile.

Hippocrates wrote of propolis as a medicine respectfully but vaguely, as did Pliny, who reported that it was “of great use for medicaments” and that it was “used by most people as a substitute for galbanum” (a widely used astringent resin). Dioscorides describes it more specifically as “the yellow bee-glue that is of a sweet scent … and easy to spread after the fashion of mastick. It is extremely warm, and attractive and drawing out thornes and splinters. Being suffumigated it doth help old coughs and being applied doth take away the lichens. It is found about ye mouthes of hives.”

Most bee glue is about 50 percent tree resin, 30 percent wax, 10 percent essential oils, and 10 percent pollen. In addition to keeping the hive airtight and upright, the odor of the tree resins in the propolis acts as a kind of mothball, deterring pestilent invaders from the hive. Tree gums and oils also offer proven antibacterial and antiviral properties, which the bees exploit, spreading a thin layer of this defensive sheen about the hive as if varnishing their home with Lysol. At the entrance of a hive, the application is especially thick, acting as a decontamination zone for bees returning to the hygienic nest.

Propolis was traditionally harvested by scraping it from the hive, which is as laborious and unpleasant as stripping furniture in a swarm of bees. Now plastic screens are placed inside a colony, inspiring the bees to diligently solder the holes full of propolis, which can be harvested when the screens are removed. Though it is not recommended for household caulking, propolis has been found to be useful in medicine. Many of its properties have not been studied, but the superglue of the bees contains benzoic acid, ketone, quercetin, caffeic acid, acacetin, and pinostrobin, all of which have antiviral, antifungal, anti-inflammatory, and antihistamine powers. Anecdotal evidence suggests that the sticky defense of the bees can be used to combat a variety of infections and inflammations of the human fortress.

While pollen and propolis both have ancient and historic medical pedigrees, royal jelly and bee venom have begun to be exploited only in recent decades. Royal jelly is the milky pabulum that worker bees secrete and feed exclusively to a select few fertilized eggs, one of which, on this special diet, will grow into a queen. An elixir of proteins, fats, carbohydrates, fatty acids, amino acids, and vitamins (with a heavy concentration of Bs), this royal food, like many hive products, has been shown to have potent antibacterial and antifungal powers, which may be useful in treating ulcers, indigestion, colds, and infections.

Because of its phenomenal transformative role in the hive, some people have supposed that royal jelly would produce similarly wondrous makeovers in humans. Alas, it works for bee royalty only. Royal jelly packs a load of natural nutrients that strengthen and nourish both body and skin, but it won’t transform users into long-living, vastly reproductive queens. Imagine Poppea, Nero’s murdered vainglorious wife, getting her hands on a substance that created strong, beautiful, and fertile queens who lived thirty times longer than their mates!

Even the bees’ sting produces certain benefits. Charlemagne is said to have crushed live bees onto his aching arthritic limbs, and whole bees, alive and dead, were used frequently in medieval pres-criptions. In her Physica, Hildegard prescribed “for anyone on whom ganglia grow, or who has had some limb moved from its place, or who has any crushed limbs, take bees that are not alive, but which have died, in a metallic jar. Put a sufficient amount on a linen cloth, and sew it up. Soak this cloth, with the bees sewn within, in olive oil, and place it over the ailing limb. Do this often, and he will be better.” A medical dispensary from 1895 describes Apis Extract, which was produced by placing a bunch of bees in a jar and shaking it, exciting the frustrated bees to coat the inside with venom. Mixed with alcohol, the resulting liquid was used on infections, rashes, and other inflammations. What Charlemagne and Hildegard were after, though they might not have realized it, was bee venom. It stimulates the adrenal glands to produce cortisol, a powerful anti-inflammatory, which might have soothed the king’s arthritis. Apamin, a neurotoxin in bee venom, anesthetizes the sting site, which would have made it numbingly appropriate for Hildegard’s patient with a crushed limb.

Bee venom has been commercially harvested only in the last thirty years or so. At first it was squeezed from agitated bees onto an absorbent cloth. More recently a contraption involving an electrified glass plate has been used. When the bees contact the glass near a hive entrance, they receive a mild electrical shock and extend their stingers in alarm, spurting a drop of venom in surprise. Collected from the glass plates, the venom is injected or smeared in creams onto aching joints and arthritic limbs. Those who feel that the sting experience is more stimulating and effective than shots or creams have turned to live bees (purchased from local beekeepers) for their therapy. A carefully applied sting or two numbs the site and stimulates the immune, anti-inflammatory, and circulatory systems, which chain of responses may be useful in combating multiple sclerosis, arthritis, lupus, and chronic fatigue syndrome.

Edmund Hillary, the first man to summit Mount Everest in 1953 at the age of 34, was from a New Zealand beekeeping family. Perhaps his amazing health and fitness came in some part from an inadvertent lifelong program of apitherapy, eating lots of honey and pollen and receiving numerous doses of bee venom. In his autobiography, Nothing Venture, Nothing Win, Hillary describes beekeeping and his program of daily stings, which both sound a lot like Smiley’s.

It was a good life—a life of open air and sun and hard physical work. And in its way a life of uncertainty and adventure: a constant fight against the vagaries of the weather. We had 1600 hives of bees spread around the pleasant dairyland south of Auckland, occupying small corners on fifty different farms. We were constantly on the move from site to site…. We never knew what our crop would be until the last pound of honey had been taken off the hives; it could range from a massive sixty tons to a miserable twenty or less. But all through the exciting months of the honey flow the dream of a bumper crop would drive us on through long hours of hard labour; manhandling thousands of ninety pound boxes of honey comb for extracting … and grimacing at our daily ration of a dozen, or a hundred beestings.

Nearing fifty, Smiley is also in amazingly good shape, which he attributes in part to his honey consumption. “I eat honey six days out of seven,” he says, “and I definitely heal faster since I’ve been working in honey.” On the benefits of bee stings, he’s less sure. “I’ve got arthritis, and all those bee stings haven’t helped me at all.” George, smoking a cigarette as he mends hive frames, wags his hands loosely up and down, and says, “I let ’em sting me on the wrists.” He has tendonitis from lifting heavy frames out of their boxes thousands and thousands of times. “I got ’em to sting me as much as possible on my wrists, and it works,” he says “Feels much better. Until the numbness wears off.” Smiley considers this. He hasn’t specifically tried to get the bees to sting him on his back, where the arthritis hurts, or on his wrists, which are sore from beekeeping and, before that, oystering. “I know you have to put them on the right spot. I’ll try it,” he drawls. “I just don’t know if I can take the pain.” They both laugh as Smiley slaps a knee.

While the bees are resting in their big medicine ball up north, Smiley and George build hundreds of boxes, wire and repair thousands of frames, sell Christmas honey, medicate, feed, and constantly check on their clustering charges. By January he’ll bring them all back down to Wewahitchka to catch the first nectar flows. In February and March he’ll start making increases and housing his new livestock. By the middle of April he’ll be inspecting tupelo buds, trying to predict when the blossoms will spring forth. And then it all starts again. “This job is never, ever done,” says Smiley with fatigued wonder. “Every year’s different. You’re doing the same things, but every year’s different.”

Standing in the front yard on a cold winter day, he looks at the new pink house that the bees built for him. He heads toward his work area to build some new homes for them, thinking about all the new bees he’ll nurture next year and all the honey and money they’ll make for him. “You gotta take care of your bees,” he says thoughtfully. “You take care of your bees, and they’ll take care of you.”