Chapter 2

Stress Explained (In Surprisingly Few Pages)

In This Chapter

Understanding stress

Understanding stress

Looking at a model of stress

Looking at a model of stress

Finding the right balance

Finding the right balance

You’ve heard the word stress a thousand times. But if you’re pressed to explain the concept, you may find yourself a little stuck. Intuitively, you know what stress is, but explaining it isn’t easy. This chapter helps you answer the question, “What exactly is stress?” The next time you find yourself at a dinner party and someone asks, “Does anyone here know what stress is?” you can grin knowingly, raise your hand, and proceed to dazzle and delight your tablemates.

So What Is Stress Anyhow?

Defining stress isn’t easy. Professionals who’ve spent most of their lives studying stress still have trouble defining the term. As one stress researcher quipped, “Defining stress is like nailing Jell-O to a tree. It’s hard to do!” Despite efforts during the last half century to assign a specific meaning to the term, no satisfactory definition exists. Defining stress is much like defining happiness. Everyone knows what it is, but no one can agree on a single definition.

“Sorry, but I really need a definition”

Perhaps you always began your high-school English essays with a dictionary definition (“Webster defines tragedy as . . .”), and you still have to start with a definition. Okay, here’s the scientific definition:

Stress describes a condition where an environmental demand exceeds the natural regulatory capacity of an organism.

Put in simpler terms, stress is what you experience when you believe you can’t cope effectively with a threatening situation. If you see an event or situation as only mildly challenging, you probably feel only a little stress; however, if you perceive a situation or event as threatening or overwhelming, you probably feel a lot of stress. So, having to wait for a bus when you have all the time in the world triggers little stress. Waiting for that same bus when you’re late for a plane that will take off without you triggers much more stress.

This difference between the demands of the situation and your perception of how well you can cope with that situation is what determines how much stress you feel.

Stress causes stress?

Part of the problem with defining stress is the confusing way the word is used. We use the word stress to refer to the thing or circumstance out there that stresses us (stress = the bus that never comes, the deadline, the traffic jam, the sudden noise, and so on). We then use the same word to describe the physical and emotional discomfort we feel about that situation (stress = anxious, headachy, irritated, and so on). So we end up feeling stress about stress! This can be confusing. In this book I try to use “stressor” or “stress trigger” when referring to a potentially stressful situation or event, and “stress” for your emotional and physical responses. But because the term is used so loosely, I won’t be terribly consistent either. My advice? Don’t worry about it. This chapter helps you understand what stress is all about, even if you can’t spout an exact definition.

How This Whole Stress Thing Got Started

Believe it or not, you have stress in your life for a good reason. To understand why stress can be a useful, adaptive response, you need to take a trip back in time.

Imagining you’re a cave person

Picture this: You’ve gone back in time to a period thousands of years ago when men and women lived in caves. You’re roaming the jungle dressed in a loincloth and carrying a club. Your day, so far, has been routine. Nothing more than the usual cave politics and the ongoing problems with the in-laws. Nothing you can’t handle. Suddenly, on your stroll, you spot a tiger. This is not your ordinary tiger; it’s a saber-toothed one. You experience something called the fight-or-flight response. This response is aptly named because, just then, you have to make a choice: You can stay and do battle (that’s the fight part), or you can run like the wind (the flight part, and probably the smarter option here). Your body, armed with this automatic stress response, prepares you to do either. You are ready for anything. You are wired.

Surviving the modern jungle

You’ve probably noticed that you don’t live in a cave. And your chances of running into a saber-toothed tiger are slim, especially because they’re extinct. Yet this incredibly important, life-preserving stress reaction is still hard-wired into your system. And once in a while, it can still be highly adaptive. If you’re picnicking on a railroad track and see a train barreling toward you, an aggressive stress response is nice to have. You want to get out of there quickly.

In today’s society, you’re required to deal with few life-threatening stressors — at least on a normal day. Unfortunately, your body’s fight-or-flight response is activated by a whole range of stressful events and situations that aren’t going to do you in. The physical dangers have been replaced by social and psychological stress triggers, which aren’t worthy of a full fight-or-flight stress response. But your body doesn’t know this, and it reacts the way it did when your ancestors were facing real danger.

Imagine the following modern-day scenario: You’re standing in an auditorium in front of several hundred seated people. You’re about to give a presentation that is important to your career. You suddenly realize that you’ve left several pages of your prepared material at home on your nightstand. As it dawns on you that this isn’t just a bad dream you’ll laugh about later, you start to notice some physical and emotional changes. Your hands are becoming cold and clammy. Your heart is beating faster, and you’re breathing harder. Your throat is dry. Your muscles are tensing, and you notice a slight tremor as you hopelessly look for the missing pages. Your stomach feels a little queasy, and you notice an emotion that you would definitely label as anxiety. You recognize that you’re experiencing a stress reaction. You now also recognize that you’re experiencing the same fight-or-flight response that your caveman ancestors experienced. The difference is, you probably won’t die up there at that podium, even though it feels like you will.

In the modern jungle, giving that presentation, being stuck in traffic, confronting a disgruntled client, facing an angry spouse, or trying to meet some unrealistic deadline is what stresses you. These far-less-threatening stressors trigger that same intense stress response. It’s overkill. Your body is not just reacting; it’s overreacting. And that’s definitely not good.

Understanding the Signs of Stress

An important part of managing your stress is knowing what your stress looks like. Your stress responses can take different forms: bodily changes, emotional changes, and behavioral changes. This section gives you a clearer picture of what these changes look like. Although they look very different, they are all possible responses you may have when confronted with a stressful situation.

Your body reacts

When you’re in fight-or-flight mode, your physiological system goes into high gear. Often your body tells you first that you’re experiencing stress. You may notice that you’re breathing more quickly than you normally do and that your hands feel cool and more than a little moist. But that’s just for starters.

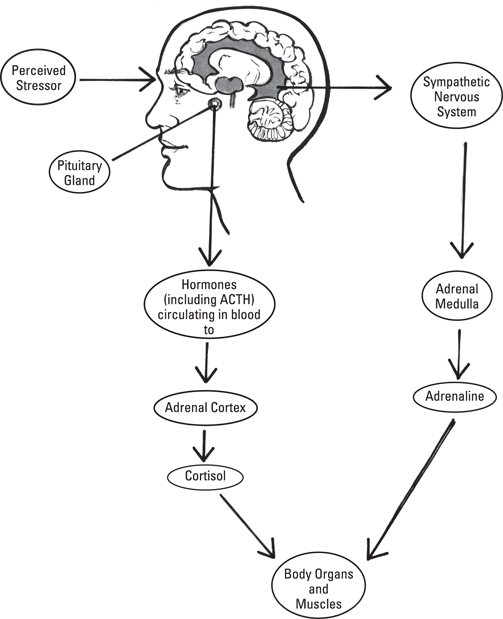

If you could see what’s happening below the surface, you’d also notice some other changes. Your sympathetic nervous system, one of the two branches of your autonomic nervous system, is producing changes in your body. Your hypothalamus, a small portion of your brain located above the brain stem, stimulates your pituitary, a small gland near the base of your brain. It releases a hormone into the bloodstream called adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). When that hormone reaches your adrenal glands, they in turn produce extra adrenalin (also known as epinephrine) along with other hormones called glucocorticoids. (Cortisol is one.)

This biochemical domino effect causes an array of other remarkable changes in your body. Figure 2-1 shows a diagram to help you see what’s going on.

Illustration by Pam Tanzey

Figure 2-1: How stress affects you.

More specifically, here are some highlights:

Your heart rate speeds up, and your blood pressure rises. (More blood is pumped to your muscles and lungs.)

Your heart rate speeds up, and your blood pressure rises. (More blood is pumped to your muscles and lungs.)

You breathe more rapidly, and your nostrils flare, causing an increased supply of air.

You breathe more rapidly, and your nostrils flare, causing an increased supply of air.

Your digestion slows. (Who’s got time to eat?)

Your digestion slows. (Who’s got time to eat?)

Your blood is directed away from your skin and internal organs and shunted to your brain and skeletal muscles. Your muscles tense. You feel stronger. You are ready for action.

Your blood is directed away from your skin and internal organs and shunted to your brain and skeletal muscles. Your muscles tense. You feel stronger. You are ready for action.

Your blood clots more quickly, ready to repair any damage to your arteries.

Your blood clots more quickly, ready to repair any damage to your arteries.

Your pupils dilate, so you see better.

Your pupils dilate, so you see better.

Your liver converts glycogen into glucose, which teams up with free fatty acids to supply you with fuel and some quick energy. (You’ll probably need it.)

Your liver converts glycogen into glucose, which teams up with free fatty acids to supply you with fuel and some quick energy. (You’ll probably need it.)

In short, when you’re experiencing stress, your entire body undergoes a dramatic series of physiological changes that readies you for a life-threatening emergency. Clearly, stress has adaptive survival potential. Stress, way back when, was nature’s way of keeping you alive.

Your feelings and behavior change

Your body isn’t the only thing that responds to a stressor. You also react to a stressor with feelings and emotions. A partial list of emotional symptoms includes feeling anxious, upset, angry, sad, guilty, frustrated, hopeless, afraid, or overwhelmed. Your emotional reactions may be minor (“I’m a wee bit annoyed” or “I’m a bit concerned”) or major (“I’m furious!” or “I’m very anxious!”).

Together your physiological responses and emotional reactions can activate changes in your behavior. These changes help you “fight” or help you “flee.” Fight or flight may not be an appropriate response to a non-life-threatening situation such as misplacing your keys or failing your driving test. The right amount of anxiety can motivate adaptive behavior, such as doing your best and working toward important goals. However, too much anxiety, too much anger, or too much of some other emotional trigger can cause you to over-react or under-react. Annoyance can become anger, and concern can turn into anxiety. Excessive emotion can result in inappropriate responses. You may act too angrily, quarrel, and later regret what you said or did. If you’re feeling anxious or fearful, you may go in the other direction. You may withdraw, avoid, and give up too quickly.

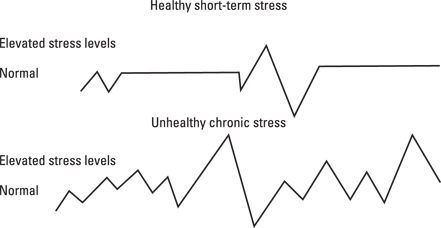

Illustration by Wiley, Composition Services Graphics

Figure 2-2: A comparison of healthy short-term stress and unhealthy chronic stress.

Understanding Stress Is as Simple as ABC

One of the best ways to understand stress is to look at a model of emotional distress elaborated by psychologist Albert Ellis. He calls his model the ABC model, and it’s as simple as it sounds:

A → B → C where

A is the Activating event or triggering situation. It’s the “stressor.”

A is the Activating event or triggering situation. It’s the “stressor.”

B is your Beliefs, thoughts, or perceptions about A.

B is your Beliefs, thoughts, or perceptions about A.

C is the emotional, physical, and behavioral Consequence or “stress” that results from holding these beliefs.

C is the emotional, physical, and behavioral Consequence or “stress” that results from holding these beliefs.

In other words,

A potentially stressful situation → your perceptions → your stress (or lack of stress).

Real-life examples make this model more understandable. Following are two situations that may seem familiar.

Consider one of the more common sources of stress in our lives: the fear of being late. You’re in a taxi headed for the airport, where you’ll board a plane for Philadelphia to interview for a job. Traffic is heavy, and you didn’t expect that. Your palms are sweaty, and your breathing is rapid and shallow. You’re feeling anxious. You are stressed out!

Using the ABC model of stress, the sequence looks something like this:

A → B → C

Late for the plane → “I’m never going to make it, and I won’t get this job!” → Anxiety and panic with sweaty palms and rapid, shallow breathing

Or consider this scenario: You’re trying to get your two kids off to school in the morning. Your husband, who is normally terrific at helping, is on his way to Philadelphia for a job interview. He normally drops off the older child at school while you take your younger daughter to day care. You have a job, too, and today you’re expected to show up for an important 9 o’clock meeting. The plan was for the three of you to leave earlier than usual so you would have time to drop them both off. But this morning your daughter woke up crying and feeling sick. You’re caught off guard. You don’t have a plan B and certainly not a plan C. You have to scramble to figure out whom to call and what to do. You feel anxious and panicky. You’re more irritable. Your breathing is off. You’re feeling very stressed.

With the ABC model, your stress looks something like this:

Important meeting this morning and daughter is not feeling well → “OMG! What do I do? I can’t skip this meeting!” → Anxiety and panic

Managing Stress: A Three-Pronged Approach

This three-pronged model of dealing with stress provides you with a useful tool to help you understand the many ways you can manage and control your stress. You have three major choices, outlined in the following sections.

1. Managing your stressors

The events that trigger your stress can range from the trivial to the dramatic. They can be very minor — a hassle such as a broken shoelace, a crowded subway, or the world’s slowest check-out line. They can be more important — losing your wallet, hearing sharp words from your boss, or getting a bad haircut a week before your wedding. The list of more serious stressors can be even more dramatic — a divorce, a serious illness, the loss of a job, or the loss of a loved one. The number of potential stressors is endless.

Changing your “A” means altering, minimizing, or eliminating your potential stressors. Following are some examples of what this may look like:

|

Potential Stressor |

Modified Stressor |

|

A crowded commute |

Leaving home earlier or later |

|

Constant lateness |

Learning time-management skills |

|

Conflict with relatives |

Spending less time with them |

|

Anger about your golf game |

Taking some golf lessons |

|

A cluttered home |

Becoming better organized |

|

Dissatisfaction with your job |

Looking for another job |

|

High credit-card bills |

Spending less |

|

Missed deadlines |

Starting projects sooner |

|

Angst about the subway |

Taking the bus |

I can hear you saying, “Give me a break! What planet does this guy live on? I can’t quit my job! I have to see my annoying relatives!” And in many cases you’re right. Often you can’t change the world or even what goes on in your own house. You want to change what other people think or do? Good luck! But you can sometimes minimize or even eliminate a potential stressor. This ability is strengthened if you have the relevant skills. In Chapters 7 and 8, I discuss how you can develop better problem-solving and time-management skills and become more organized. Changing your world isn’t always possible, but when it is, it’s often the fastest route to stress relief.

2. Changing your thoughts

Even if you can’t significantly change the situations and events that are triggering your stress, you can change the way you perceive them. What happens at “B” — your beliefs, thoughts, perceptions, and interpretations — is critical in determining how much stress you feel. Whenever you perceive a situation or event as overwhelming or beyond your control, or whenever you think you can’t cope, you experience stress. You may find that much, if not most, of your stress is self-induced, and you can learn to see things differently. So, if you’re waiting in a long line, perhaps you’re thinking, “I just can’t stand this! I hate waiting! Why can’t they figure out a better way of doing this? I hate lines! I hate lines! I hate lines!” Chances are, you’re creating more than a little stress for yourself. On the other hand, if you’re thinking, “Perfect! Now I have time to read these fascinating articles on alien babies and celebrity cellulite in the National Tattler,” you’re feeling much less stress. Your thinking plays a larger role than you may believe in creating your stress.

3. Managing your stress responses

Even if you can’t eliminate a potential stressor and can’t change the way you view that situation, you can still manage your stress by mastering other skills. You can change the way you respond to stress. You can learn how to relax your body and quiet your mind. In Chapters 4 and 5, I show you how to reverse the stress response — how to turn off your stress and recover a sense of calm.

Tuning Your Strings: Finding the Right Balance

Stress is part of life. No one makes it through life totally stress free, and you wouldn’t want to. You certainly want the good stress, and you even want some of the stress that comes with dealing with life’s challenges and disappointments. But too much (or prolonged) stress can become a negative force, and it can rob you of much of life’s joy. Too little stress means you’re missing out, taking too few risks, and playing it too safe. Finding the right amount of stress is like finding the right tension in a violin string. Too much tension and the string can break; too little tension and there is no music.

You want to hear the music, without breaking the strings.

“Oops, pardon my English!”

“Oops, pardon my English!” What makes stress such a problem — both physiologically and emotionally — is that your stress can be continuous and ongoing. Modern life demands much of us, and keeping up with these demands means lots of stress. A stressor here and there, now and then — that you can handle. If you’re stressed out only once in a while, stress isn’t really a concern. Your body and mind react, but you soon recover and return to a more relaxed state. But too often we experience a near-continuous stream of stressors. We don’t get enough recovery time.

What makes stress such a problem — both physiologically and emotionally — is that your stress can be continuous and ongoing. Modern life demands much of us, and keeping up with these demands means lots of stress. A stressor here and there, now and then — that you can handle. If you’re stressed out only once in a while, stress isn’t really a concern. Your body and mind react, but you soon recover and return to a more relaxed state. But too often we experience a near-continuous stream of stressors. We don’t get enough recovery time.