Chapter 8

Finding More Time

In This Chapter

Identifying your time-management challenges

Identifying your time-management challenges

Making time for yourself

Making time for yourself

Getting more done in less time

Getting more done in less time

Overcoming procrastination

Overcoming procrastination

Have you noticed how quickly your days fill up? You often find yourself hurried, harried, and rushing to do all that you feel has to be done. Putting out fires, dealing with last-minute crises, and taking care of unending details leave little spare time for anything else. Add to that a busy job, a family, and at least a few other obligations, and you notice that your stress level is escalating. And something else is happening: You have less and less time to spend on the things that you really enjoy and that bring you satisfaction. Fortunately, managing your time more effectively is something you can master.

This chapter gives you direction and strategies to help you manage your time more efficiently and effectively, and reduce your time-related stress.

For even more information on this topic, try Successful Time Management For Dummies, by Dirk Zeller (Wiley).

Determining Whether You Struggle with Time Management

I don’t have enough time for myself, my family, or my friends.

I don’t have enough time for myself, my family, or my friends.

I waste too much time.

I waste too much time.

I’m constantly rushing.

I’m constantly rushing.

I don’t have enough time to do the things I really enjoy.

I don’t have enough time to do the things I really enjoy.

I frequently miss deadlines or am late for appointments.

I frequently miss deadlines or am late for appointments.

I spend almost no time planning my day.

I spend almost no time planning my day.

I almost never work with some kind of prioritized to-do list.

I almost never work with some kind of prioritized to-do list.

I have difficulty saying no to others when they make demands on my time.

I have difficulty saying no to others when they make demands on my time.

I rarely delegate tasks and responsibilities.

I rarely delegate tasks and responsibilities.

I procrastinate too often.

I procrastinate too often.

Checking off only one or two items on this list suggests that your time-management skills require only a tune-up. Checking off more than four of them suggests that your time-management skills may be in need of a major overhaul.

Being Mindful of Your Time

An important step in changing the way you manage your time is becoming aware of how you use your time. Without awareness, your time management can become a victim of your time-wasting patterns. As I discuss in Chapter 6, much of your life is lived on auto-pilot. You repeat the same patterns of thinking and behavior, failing to step away and consider how you’re using your time. The price you pay ranges from the minor (lateness, procrastination, missed deadlines) to the more dramatic (missed opportunities and life experiences).

In this section, I show you how to be more mindful about time management to get the results you want.

Knowing where your time goes

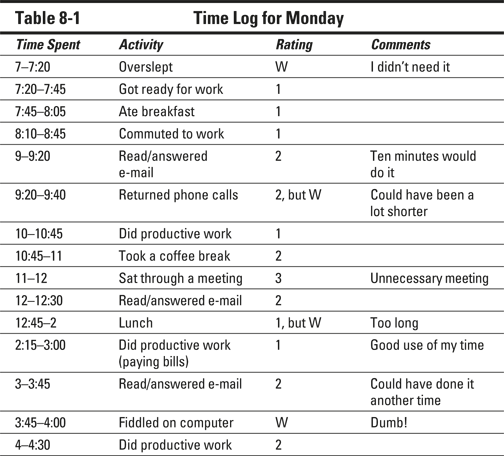

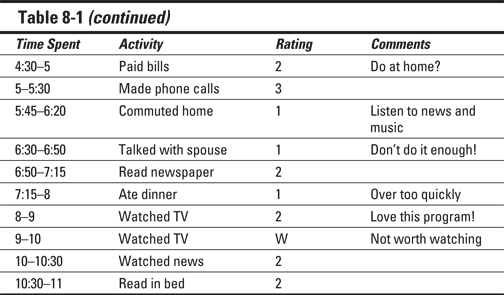

For a short period of time, perhaps a day or two, keep a simple time log. A sheet of paper will do or, if you’re more comfortable with your electronic device, use that. At convenient times during your day, enter what you did, or are doing, in the appropriate time slots. Don’t become compulsive about this; you don’t have to make it exact to the minute. However, be sure to record your electronic time usage — those times when you checked your e-mail, made or received a phone call, texted or IM-ed, visited social-networking sites, or surfed the Net. A sampling of a day or two should supply enough data to give you a rough picture of how you use — or misuse — your time. Use this simple rating code:

1 = Great use of my time

2 = Okay use of my time

3 = So-so use of my time

W = Waste of my time

Also add some comments that reflect how you feel about the way you used that time.

Table 8-1 gives you a sample of what one day may look like.

Figuring out what you want more time for

As an exercise, grab a sheet of paper and jot down activities that you would like to spend more time doing. This exercise helps you get in touch with those activities that you value and derive satisfaction from.

The following is a sample of general items you may want to consider. (You can, of course, add others.)

Spending time with your family and friends

Spending time with your family and friends

Advancing your job or career

Advancing your job or career

Pursuing a hobby or interest

Pursuing a hobby or interest

Reading

Reading

Exercising

Exercising

Nurturing your soul

Nurturing your soul

Volunteering for community activities

Volunteering for community activities

Traveling

Traveling

Sleeping

Sleeping

Knowing what you want to spend less time doing

Knowing what you want to spend more time doing is only half the battle. Knowing what you don’t want to spend time doing is just as important. Here are some things I wish I spent less time doing. Make a list of your own.

Working late at night and on weekends

Working late at night and on weekends

Doing office paperwork

Doing office paperwork

Attending events I don’t enjoy

Attending events I don’t enjoy

Cleaning the house

Cleaning the house

Doing laundry

Doing laundry

Spending time with people I don’t enjoy

Spending time with people I don’t enjoy

Surfing the Web

Surfing the Web

Watching so much television

Watching so much television

Your goal is to fill your life with more of the things you want to do — things that bring more meaning and joy to your life. This means knowing how to minimize time spent doing the things you have to do.

Minding your time with cues and prompts

One good way of becoming mindful of your time is to use naturally occurring cues and prompts as signals to stop for a moment, take a breath, and consider how you’re using your time. A prompt or cue can take various forms. It can be as simple as turning on your computer or beginning a new task. These basic behaviors prompt you to mentally step away from what you’re doing and take a more careful look at what you have done and what you will do.

You can also introduce cues or prompts that are not naturally occurring. Stick a small paper dot on your watch face or use that photograph of your last family vacation as reminders to become more mindful of what you’re doing or not doing.

Here are some other possible cues and prompts that could act as reminders:

Hanging up after a phone call

Hanging up after a phone call

Feeling the urge to check your e-mail

Feeling the urge to check your e-mail

Leaving your office or cubicle

Leaving your office or cubicle

Sending the kids off to school

Sending the kids off to school

Finishing a task

Finishing a task

Taking a bathroom break

Taking a bathroom break

Ending a meal

Ending a meal

Checking the time

Checking the time

Turning on the TV

Turning on the TV

Thinking of visiting your favorite social-media site

Thinking of visiting your favorite social-media site

So, instead of automatically checking your e-mail every ten minutes or turning on the TV every time you’re bored, use the behaviors as your cues to stop what you’re about to do, step back mentally, take a breath or two, and gain some emotional distance. When you have that distance and awareness, ask yourself some pertinent questions that can help you evaluate how you’re about to use your time.

Questioning your choices and changing behaviors

One great way of creating awareness is to have some questions ready to ask yourself. These can free you from the grip of auto-pilot and set a more productive course. Here are a few to help you get started:

“Am I making the best use of my time right now?”

“Am I making the best use of my time right now?”

“Am I procrastinating and avoiding doing something more important?”

“Am I procrastinating and avoiding doing something more important?”

“Could I be doing what I’m doing in a more efficient way?”

“Could I be doing what I’m doing in a more efficient way?”

“Could I delegate or share this task with someone else?”

“Could I delegate or share this task with someone else?”

“Do I really need to check my e-mail so frequently?”

“Do I really need to check my e-mail so frequently?”

“Do I really need to be on the Internet right now?”

“Do I really need to be on the Internet right now?”

“Should I really be watching TV right now?”

“Should I really be watching TV right now?”

Rather than answer these questions with a simple yes or no, expand your answer to include additional material that either strengthens your rationale for doing what you plan to do or provides you with strong counter-arguments motivating you to spend your time doing something else. For example, your internal dialogue might sound something like this:

“Okay, I’m about to pick up the TV remote. Is there something on now that I really want to watch? Not really. I’m a little bored and am avoiding doing stuff that I really should be doing. Watching TV is fine, but not right now. What could I be doing now that could be more important, more satisfying, or even more fun? What about hitting the gym or finishing that article? Watch TV later when there’s something good on, and use it as a reward for doing other things first.”

By introducing this “wise voice,” you create a strong ally that can defend or revise how you spend your time. This makes it more difficult to be seduced by your avoidant automatic behavior. This awareness and self-talk makes it more likely that your use of time will be productive and worthwhile.

Becoming a List Maker

Making lists might seem so obvious and sooo last century, yet lists can be one of your better time-management tools. I suggest that you work with three lists:

A master to-do list. This list is your source list, detailing all the tasks and involvements that you want to accomplish. This is your primary list.

A master to-do list. This list is your source list, detailing all the tasks and involvements that you want to accomplish. This is your primary list.

A will-do-today list. This list details how you want to spend your time today.

A will-do-today list. This list details how you want to spend your time today.

A will-do-later list. This list enables you to schedule tasks in the coming days or weeks.

A will-do-later list. This list enables you to schedule tasks in the coming days or weeks.

All these lists work together, providing you with a comprehensive time-management plan.

Starting with a master to-do list

You want to start with a master to-do list. Simply create a list of things you want to do or have to do either now or in the near future. Try to rank these items in order of importance, putting the more important ones first.

To help you rate the importance of the things on which you spend your time, try using this simple rating system:

1 = High priority (highly valued or important to me)

2 = Medium priority

3 = Low priority (not especially important to me)

D = Difficult or time-consuming

E = Easy or enjoyable

Q = Quick! Could do this in less than five minutes

Here is a sample of my current master to-do list:

|

To Do |

Priority/Rating |

|

See my patients |

1 |

|

Call plumber re: water heater |

1 |

|

Pay estimated taxes |

1 |

|

To Do |

Priority/Rating |

|

Pay phone bill |

1-Q |

|

Look into refinancing |

|

|

mortgage |

1-D |

|

Finish Chapter 8 |

1-D |

|

Buy two books |

2-E |

|

Clean bedroom |

2 |

|

Paint Katy’s room |

2 |

|

Get to the gym |

2 |

|

Call Aunt Rose |

2-E |

|

Get a haircut |

2 |

|

Do billing paperwork |

2 |

|

Pick up printing paper |

1-Q |

|

Get plane tickets for trip |

2 |

|

Pick up meds |

2 |

|

Download photos |

2-E |

|

Download new music |

3-E |

|

Pick up lunch food |

2-E |

Review and update your list daily, adding items and tasks as they come up and removing tasks when they are completed or become irrelevant.

Creating a will-do-today list

When you have your master to-do list in hand, you’re ready to create your more specific will-do-today list. Actually, this looks more like a daily planner than a usual list. It schedules how you want to spend your time today. This can be created the night before or first thing in the morning. You’ll need a day planner, either paper or electronic. Both will work well.

Working from your master list, schedule your day. Enter the activities and tasks, work and personal, that you’d like to accomplish today. Table 8-2 shows a sample of what one of my “planned” days looks like.

Table 8-2 Will Do Today: Tuesday, January 5

|

Time |

Task |

Outcome |

|

7:30 |

Create my daily to-do list; check e-mail |

|

|

8 |

See patient A |

|

|

8:45 |

Make calls; send e-mail |

|

|

9 |

See patient B |

|

|

9:45 |

Make calls; send e-mail |

|

|

11 |

See patient C (cancelled but paid estimated taxes instead) |

|

|

12 |

See patient D |

|

|

12:45 |

Eat lunch |

|

|

1 |

See patient E |

|

|

1:45 |

Make calls (Aunt Rose); check e-mail |

|

|

2 |

Do insurance billing (needs more time) |

|

|

2:45 |

Pay phone bill |

|

|

3 |

Go to the gym |

|

|

4 |

See patient F |

|

|

4:45 |

Buy plane tickets (try again tomorrow) |

|

|

5 |

See patient G |

|

|

5:45 |

Return phone calls |

|

|

6 |

See patient H |

|

|

7 |

Work on chapter at home |

|

|

8 |

Work on chapter at home |

|

|

8:30 |

Have dinner; watch news |

|

|

9 |

Have dinner; watch news |

|

|

9:30 |

Watch TV |

|

|

10 |

Read in bed |

|

|

11 |

Sleep |

|

Okay, I realize my days are pretty repetitive. Your days, I’m quite sure, are more varied, and more problematic in terms of time management.

Having a will-do-later list

As you look at your master to-do list and daily will-do-today list, you may decide that some items would be best done a day or two (or five) later. You need an extension of your will-do-today list where you can enter tasks to be done later on. Enter those tasks into your weekly or monthly planner. These may be tasks that can’t be done until an earlier part is finished or until you obtain some additional information. It may be that the person you need to deal with won’t be in the office until later in the week. It may simply be that you don’t get around to it. Whatever the reason, keeping a longer-term list gives you more flexibility and comprehensiveness.

Keeping some tips in mind as you make your lists

Here are some suggestions and ideas to keep in mind as you put your daily lists together. Remember, not every idea works equally well for everybody. Give each suggestion some thought and give it a fair try. Ultimately you’ll put together your own unique time-management ideas that best match your style and personality.

Don’t overdo it. Don’t make your to-do list so long that it becomes unwieldy. Watch the number of tasks you stick on that list.

Don’t overdo it. Don’t make your to-do list so long that it becomes unwieldy. Watch the number of tasks you stick on that list.

Don’t schedule the “guaranteed to happen” stuff. Don’t include tasks you know for certain you’ll be doing. On my daily list, for example, I don’t include activities that will automatically be done, such as commuting to and from work and eating dinner. (I actually end up with a very short list.) These tasks happen without my prompting and don’t require any special motivation or pre-planning. These are usually not time wasters for me. Again, come up with a daily plan that works best for you.

Don’t schedule the “guaranteed to happen” stuff. Don’t include tasks you know for certain you’ll be doing. On my daily list, for example, I don’t include activities that will automatically be done, such as commuting to and from work and eating dinner. (I actually end up with a very short list.) These tasks happen without my prompting and don’t require any special motivation or pre-planning. These are usually not time wasters for me. Again, come up with a daily plan that works best for you.

Do the important tasks first. Starting a new year, a new week, or even a new day often fills us with resolve. We begin our days with a higher level of motivation and determination. It probably makes sense to schedule the tougher, less desirable tasks first thing in your day. Pick a more difficult high-priority task first. Commit to staying with that task long enough to finish it or make a significant amount of progress.

Do the important tasks first. Starting a new year, a new week, or even a new day often fills us with resolve. We begin our days with a higher level of motivation and determination. It probably makes sense to schedule the tougher, less desirable tasks first thing in your day. Pick a more difficult high-priority task first. Commit to staying with that task long enough to finish it or make a significant amount of progress.

Be flexible with priorities. When you write down your daily tasks, don’t feel compelled to fill your day with all Level 1 items (the most difficult tasks). They are important and should have a place on your daily calendar. But don’t be compulsive. Plan your day knowing yourself and what will work best for you. For some, doing a challenging, difficult task first thing makes sense; for others, later in the day might work better. You can mix it up a bit, juggling the difficult tasks with the easier ones.

Be flexible with priorities. When you write down your daily tasks, don’t feel compelled to fill your day with all Level 1 items (the most difficult tasks). They are important and should have a place on your daily calendar. But don’t be compulsive. Plan your day knowing yourself and what will work best for you. For some, doing a challenging, difficult task first thing makes sense; for others, later in the day might work better. You can mix it up a bit, juggling the difficult tasks with the easier ones.

Identify your best work times. You may be a morning person. You may be a night owl. The hours right after lunch may be your least-effective working hours. Try to match your more-difficult, higher-priority tasks with your more-productive working times. Save easier tasks for times when you feel less motivated.

Identify your best work times. You may be a morning person. You may be a night owl. The hours right after lunch may be your least-effective working hours. Try to match your more-difficult, higher-priority tasks with your more-productive working times. Save easier tasks for times when you feel less motivated.

Don’t over-commit. Recognize that you may be less efficient than you expect to be. Be realistic. Be reasonable. If you do it all and have time to do more, that’s great.

Don’t over-commit. Recognize that you may be less efficient than you expect to be. Be realistic. Be reasonable. If you do it all and have time to do more, that’s great.

Break bigger tasks into smaller pieces. If you’re intimidated by the time it may take to do a major or complex task, break it up into smaller pieces and focus on one piece. It’s hard to start a task that seems overwhelming. Create smaller chunks. For example:

Break bigger tasks into smaller pieces. If you’re intimidated by the time it may take to do a major or complex task, break it up into smaller pieces and focus on one piece. It’s hard to start a task that seems overwhelming. Create smaller chunks. For example:

• Clean up the house → Clean the kitchen

• Write the chapter → Write the outline

• Pay all the bills → Pay the high-priority bills

Schedule breaks. Recognize that a break between tasks can give you a breather and even act as a reward for your impressive effort. These few minutes can be used to catch up on e-mail, make some social calls, text a friend — whatever. You can also take a quick walk, do some stretches, or do one of the many relaxation exercises I describe in Chapter 4.

Schedule breaks. Recognize that a break between tasks can give you a breather and even act as a reward for your impressive effort. These few minutes can be used to catch up on e-mail, make some social calls, text a friend — whatever. You can also take a quick walk, do some stretches, or do one of the many relaxation exercises I describe in Chapter 4.

Do the “quickies” quickly. During breaks or other down times, you may be able to knock off some easy tasks fairly quickly. Just do it. Anything that you’ve given a “Q” ranking (meaning it can be done in less than five minutes), do right away. Get it off your list.

Do the “quickies” quickly. During breaks or other down times, you may be able to knock off some easy tasks fairly quickly. Just do it. Anything that you’ve given a “Q” ranking (meaning it can be done in less than five minutes), do right away. Get it off your list.

Group similar tasks together. Save yourself a great deal of time by doing similar tasks at the same time. Grouping tasks is much more efficient and much less stressful. You can, for example:

Group similar tasks together. Save yourself a great deal of time by doing similar tasks at the same time. Grouping tasks is much more efficient and much less stressful. You can, for example:

• Pay all your bills at the same time. Designate a time to go through the bills, write the checks, address the envelopes, and mail them.

• Combine your errands. Rather than running to the store for every little item, group errands together. Keep a “Things We Need or Will Need Soon” list in a handy place and refer to your list before you dash out for that single item. An even simpler way to do this is to photocopy a master list with the common items you usually need to replace and stick it on the fridge. Check off a needed item when you notice that you’re running low. When you’ve checked off a bunch of items on the list, head to the store.

Indicate outcome. When something is completed, either cross it off your list or make a “done” comment in your outcome column. If you don’t get around to starting or finishing something, make a note about when you plan to complete the task.

Indicate outcome. When something is completed, either cross it off your list or make a “done” comment in your outcome column. If you don’t get around to starting or finishing something, make a note about when you plan to complete the task.

Update your master list. What you don’t accomplish by the end of the day should be reassessed the next day. It stays on your master list until it’s done or you deem it unimportant.

Update your master list. What you don’t accomplish by the end of the day should be reassessed the next day. It stays on your master list until it’s done or you deem it unimportant.

Use the 80/20 rule. Apply the Pareto principle, also known as the 80/20 rule, to your time-management analysis. Simply put, it states: Of the things you have to do, doing 20 percent of the most-valued tasks will provide you with 80 percent of the satisfaction you may have gotten by doing them all. In other words, skipping your lower-priority items doesn’t really cost you a whole lot in the long run. Don’t get fixated on those less-valued, less-productive activities. Ask yourself, “Would it really be so awful if I didn’t do this task?”

Use the 80/20 rule. Apply the Pareto principle, also known as the 80/20 rule, to your time-management analysis. Simply put, it states: Of the things you have to do, doing 20 percent of the most-valued tasks will provide you with 80 percent of the satisfaction you may have gotten by doing them all. In other words, skipping your lower-priority items doesn’t really cost you a whole lot in the long run. Don’t get fixated on those less-valued, less-productive activities. Ask yourself, “Would it really be so awful if I didn’t do this task?”

Minimizing your Distractions and Interruptions

It’s not only the “too much to do in too little time” that creates stress; it’s also how your time is wasted by others or yourself. Much of your time can be consumed by small interruptions or distractions that take you away from what you’re doing and thereby lengthen the time spent on the task at hand. Your distractions and interruptions may take the form of obsessively checking your e-mail while in the middle of doing something else or being sidetracked by a spouse or roommate who has “just one quick question.” Here are some suggestions to help you avoid wasted time.

Managing electronic interruptions

Whenever you can, “bundle.” Make phone calls and e-mails in batches. Rather than interrupting your schedule to make or return noncritical phone calls or send e-mails, wait until you have several items and do them all at once.

Whenever you can, “bundle.” Make phone calls and e-mails in batches. Rather than interrupting your schedule to make or return noncritical phone calls or send e-mails, wait until you have several items and do them all at once.

Just because you receive a phone call, text, e-mail, or IM doesn’t mean you have to respond to it at that moment (unless your job requires that you do!). Let things go to voicemail. Turn off the pop-up notification that alerts you to every new digital message. When you take a break or finish a task, then check your digital messages.

Just because you receive a phone call, text, e-mail, or IM doesn’t mean you have to respond to it at that moment (unless your job requires that you do!). Let things go to voicemail. Turn off the pop-up notification that alerts you to every new digital message. When you take a break or finish a task, then check your digital messages.

Respond to your messages during low-productivity times. If answering your electronic messages is critical to what you’re doing, put it on your to-do list. Build it in.

Respond to your messages during low-productivity times. If answering your electronic messages is critical to what you’re doing, put it on your to-do list. Build it in.

When you do check your digital messages, realize that you don’t have to respond to everything. Filter out the more important messages and let the less urgent stuff go until you have more time.

When you do check your digital messages, realize that you don’t have to respond to everything. Filter out the more important messages and let the less urgent stuff go until you have more time.

Whenever possible (and appropriate), use e-mail or texting rather than the telephone. It’s far more efficient and gives you more control over your time. (On the other hand, use the phone when you care about the person on the other end!)

Whenever possible (and appropriate), use e-mail or texting rather than the telephone. It’s far more efficient and gives you more control over your time. (On the other hand, use the phone when you care about the person on the other end!)

Losing the visitors

Other people can be pesky. These “others” may be family members, roommates, co-workers, or others who like to pop their heads into your space and chat whenever they get a chance. (To be fair, you may be the problem, distracting others while robbing yourself of productive time.) Some ideas:

Be polite but firm and tell your visitors that “this really isn’t a good time to talk. I absolutely have to finish this task. But I’ll get back to you.”

Be polite but firm and tell your visitors that “this really isn’t a good time to talk. I absolutely have to finish this task. But I’ll get back to you.”

Hide. If you can find a room or space that is off the beaten track and where you can do some solid work, give it a try. Sometimes a restaurant or coffee shop can work.

Hide. If you can find a room or space that is off the beaten track and where you can do some solid work, give it a try. Sometimes a restaurant or coffee shop can work.

Look unavailable. If you have a door, keep it closed. If you have an empty chair, put something on it. It can be books, files, clothing — anything that may dissuade a would-be sitter.

Look unavailable. If you have a door, keep it closed. If you have an empty chair, put something on it. It can be books, files, clothing — anything that may dissuade a would-be sitter.

Try some headphones. People tend to steer away from people with headphones on. Remember, you don’t need to be listening to anything on your headphones. Just having them on should do the trick.

Try some headphones. People tend to steer away from people with headphones on. Remember, you don’t need to be listening to anything on your headphones. Just having them on should do the trick.

Talk to your recurring interrupter. Tell the person about your problem with distractions. The person may not realize that he or she is part of your problem.

Talk to your recurring interrupter. Tell the person about your problem with distractions. The person may not realize that he or she is part of your problem.

Lowering the volume

Noise can be a subtle or not-so-subtle source of distraction. It may be a loud co-worker or street noise. Shutting your door can help, but it may not be an option. Some other suggestions:

Consider noise-canceling headphones. Use them with or without some relaxing music. Quality ear-buds can have a similar effect without your looking so anti-social.

Consider noise-canceling headphones. Use them with or without some relaxing music. Quality ear-buds can have a similar effect without your looking so anti-social.

Get a white-noise machine, which can mask a variety of distracting sounds (traffic in the street, the upstairs neighbors). You can download white-noise files and have them repeat on a playback loop.

Get a white-noise machine, which can mask a variety of distracting sounds (traffic in the street, the upstairs neighbors). You can download white-noise files and have them repeat on a playback loop.

Leave. If a task or project demands a high level of attentiveness, find a quieter place to work. Sometimes a conference room at work goes mostly unused. At home it may be another room, or possibly space in the basement or attic. Sometimes less obvious places can work. On fine days, try the park or a quiet section of a lobby in a nearby hotel. Be creative.

Leave. If a task or project demands a high level of attentiveness, find a quieter place to work. Sometimes a conference room at work goes mostly unused. At home it may be another room, or possibly space in the basement or attic. Sometimes less obvious places can work. On fine days, try the park or a quiet section of a lobby in a nearby hotel. Be creative.

Limiting your breaks

Taking a break can be a sensible and necessary part of your day. It can give you the opportunity to re-group, refresh, and start your next task with a clearer head. The problem is taking too many breaks, or taking them at the wrong times. Some suggestions:

Schedule your breaks to follow the completion of a task. This can be your reward for finishing.

Schedule your breaks to follow the completion of a task. This can be your reward for finishing.

Do something that is relaxing or even fun. It can be browsing the Internet, shopping online, or playing a digital game. Of course, it can also be listening to music, watching a video, or reading an article or a few pages of your current book.

Do something that is relaxing or even fun. It can be browsing the Internet, shopping online, or playing a digital game. Of course, it can also be listening to music, watching a video, or reading an article or a few pages of your current book.

Limit the time you take for a break. The most common trap is socializing with others for far too long. After you’ve mingled for a bit, take your coffee with you back to your space.

Limit the time you take for a break. The most common trap is socializing with others for far too long. After you’ve mingled for a bit, take your coffee with you back to your space.

Shifting your time

A more radical solution is to re-arrange the times you need to concentrate and think so as to avoid interruptions and distractions for at least part of your day. Can you get up earlier and start your day (either at home or at the office) sooner, before the distractions appear? Doing some work after the kids are in bed may be more productive than sitting at the dining-room table on a Saturday afternoon. Your office may be much quieter after most of your co-workers have left. Just consider it.

Turning it into a positive

Whenever possible, turn your interruptions into something positive. Use those interruptions as cues to step back, do some relaxing breathing, and refocus your thoughts and direction. This brief breather can be a useful reminder, making you more aware of what you were doing and what you should be doing.

Minimizing your TV time

As one of my children once commented, “Have you ever noticed how much longer the days are when you don’t watch TV?” Although some television is terrific, a lot of it is not terrific. It’s clear, at least to me, that people waste too much time watching television. I’m convinced that the quality of our lives would be greatly enriched if we watched less television.

TV reduction tactics include the following:

Use your DVR. Almost never watch a television program when it’s originally broadcast. Record the programs you like and watch them in a block, at a time you choose. You may feel left out at the water cooler, but your time management will be amazingly better.

Use your DVR. Almost never watch a television program when it’s originally broadcast. Record the programs you like and watch them in a block, at a time you choose. You may feel left out at the water cooler, but your time management will be amazingly better.

Try to cut back drastically on the time you spend watching TV. Never just randomly channel surf, sticking with the least-objectionable program. Even if you pre-record shows, watch only those shows that you really want to watch. Try to keep your TV time down to less than two hours per night.

Try to cut back drastically on the time you spend watching TV. Never just randomly channel surf, sticking with the least-objectionable program. Even if you pre-record shows, watch only those shows that you really want to watch. Try to keep your TV time down to less than two hours per night.

Make one evening a week a no-TV night. Instead of watching television, do something else. Read a book. Go to the gym. Make soup. Make love. Go to bed earlier. You can always watch that show at a later time.

Make one evening a week a no-TV night. Instead of watching television, do something else. Read a book. Go to the gym. Make soup. Make love. Go to bed earlier. You can always watch that show at a later time.

Avoid DVR pileup. When you’ve collected more recorded programs than you could possibly watch in one day of dedicated TV viewing, start winnowing. Begin deleting rather than adding to your growing collection. Use the one-month rule. If you haven’t watched it within a month, delete it.

Avoid DVR pileup. When you’ve collected more recorded programs than you could possibly watch in one day of dedicated TV viewing, start winnowing. Begin deleting rather than adding to your growing collection. Use the one-month rule. If you haven’t watched it within a month, delete it.

Winning the waiting game

You may find that much of your time is lost while waiting. It may be waiting 45 minutes for the doctor to see you; waiting for the cable guy to come for his promised 9:30 a.m. appointment (good luck with that!); waiting for your bus, subway, plane, or train to show up or depart; or waiting for that meeting to get started.

The trick to beating the waiting game is to expect that at various times you’ll find yourself having to wait — and then to put that waiting time to good use. Have some form of involvement, task, or activity easily available. This time-filling activity doesn’t have to be actual work, though it can be, but it should be something you pre-plan to do when you find yourself having to wait.

I assume that most folks these days own some form of digital device, and many automatically listen to music or play a video game. Here are some less obvious ways of putting that wait time to better use:

Read. Have a book, newspaper, magazine, or digital counterpart with you at most times. Fun reading, work-related reading, whatever.

Read. Have a book, newspaper, magazine, or digital counterpart with you at most times. Fun reading, work-related reading, whatever.

Learn. Podcasts are a welcome way to pass the time. For the last year I’ve been trying to learn Spanish via a series of podcasts. While pedaling on the elliptical or heading home from work on the subway, I master the skill of declining irregular verbs. My favorite radio shows are usually available in podcast form, too.

Learn. Podcasts are a welcome way to pass the time. For the last year I’ve been trying to learn Spanish via a series of podcasts. While pedaling on the elliptical or heading home from work on the subway, I master the skill of declining irregular verbs. My favorite radio shows are usually available in podcast form, too.

Play. Do the crossword puzzle, challenge yourself to Sudoku, or, yes, even play a computer game.

Play. Do the crossword puzzle, challenge yourself to Sudoku, or, yes, even play a computer game.

Breathe. Take this time to do some relaxation and meditation. Focus on your breathing, introduce some relaxing imagery, and turn your waiting time into a mini-vacation.

Breathe. Take this time to do some relaxation and meditation. Focus on your breathing, introduce some relaxing imagery, and turn your waiting time into a mini-vacation.

E-mail. Work on your laptop, tablet, or smartphone to read and answer your e-mail. You can also make phone calls, as long as you don’t annoy your neighbors.

E-mail. Work on your laptop, tablet, or smartphone to read and answer your e-mail. You can also make phone calls, as long as you don’t annoy your neighbors.

Work. Do actual work, whether it’s that pesky little task your boss assigned or personal tasks like balancing your checkbook.

Work. Do actual work, whether it’s that pesky little task your boss assigned or personal tasks like balancing your checkbook.

Update. Update your to-do list and daily calendar.

Update. Update your to-do list and daily calendar.

Sync. You probably own more than one digital device. By syncing your computer with your phone and tablet, you can create a continuous link with your electronic life.

Sync. You probably own more than one digital device. By syncing your computer with your phone and tablet, you can create a continuous link with your electronic life.

Getting around Psychological Roadblocks to Time Management

You probably recognize that simply knowing the tricks of time management doesn’t guarantee that you’ll put them into practice. You’re human! Your emotional and psychological dynamics come into play and can act as barriers that slow or even halt your good time-management intentions. Identifying those self-defeating patterns becomes just as necessary to effectively managing your time as is your to-do list. This section covers two of the more common time-wasting patterns. See which ones fit you and what you can do to overcome them.

Getting over your desire to be perfect

The old adage “Anything worth doing is worth doing well” is misguided. There’s nothing wrong with wanting to do something well, even very well. But when your standards are too high, and you aim for perfection, you will feel stress. Perfection is overrated. Being perfect for any longer than three minutes is hard. Whenever you strive for perfection, you fall into one of two time-wasting and stress-producing traps:

You spend more time on the task or activity than is warranted.

You spend more time on the task or activity than is warranted.

You avoid doing the task altogether for fear that you won’t do it well enough.

You avoid doing the task altogether for fear that you won’t do it well enough.

Strive for “pretty darn good” instead of “perfect.” And, sometimes, let yourself strive for “just okay.”

Overcoming procrastination

Procrastination may be one of the main time robbers and ultimate stress producers in your life. I have yet to see more than a handful of people who don’t lose time by procrastinating. By avoiding the kinds of activities that are important and valued, you wind up spending a lot of time doing activities that are less valued and less satisfying. Procrastinating on writing that letter to a loved one, updating your resume, or making that phone call to a friend almost always leads to regret.

You probably procrastinate for one of four major reasons:

Discomfort dodging. Life often involves doing things that involve some degree of effort and discomfort. When you’re experiencing low discomfort tolerance (LDT), you begin looking for ways to avoid doing that discomforting task.

Discomfort dodging. Life often involves doing things that involve some degree of effort and discomfort. When you’re experiencing low discomfort tolerance (LDT), you begin looking for ways to avoid doing that discomforting task.

Fear of failure. You’re afraid that you may not be able to do the avoided task as well as you’d like. Fear of failure and feeling bad about yourself make it less likely that you’ll do what you ought to be doing. You see failure as a reflection of your self-worth and believe that if you fail, you are a failure. You figure, mistakenly, that maybe if you avoid the task or situation, you won’t have to deal with failure. Not a great game plan for life.

Fear of failure. You’re afraid that you may not be able to do the avoided task as well as you’d like. Fear of failure and feeling bad about yourself make it less likely that you’ll do what you ought to be doing. You see failure as a reflection of your self-worth and believe that if you fail, you are a failure. You figure, mistakenly, that maybe if you avoid the task or situation, you won’t have to deal with failure. Not a great game plan for life.

Fear of disapproval. As is the case with fear of failure, you’re afraid that somebody will be displeased with your performance and disapprove of you. You over-value other people’s opinions and equate that approval or disapproval with your self-worth. Misguidedly, you avoid doing what you ought to be doing to spare yourself the bad feelings you create when you think you will be disapproved.

Fear of disapproval. As is the case with fear of failure, you’re afraid that somebody will be displeased with your performance and disapprove of you. You over-value other people’s opinions and equate that approval or disapproval with your self-worth. Misguidedly, you avoid doing what you ought to be doing to spare yourself the bad feelings you create when you think you will be disapproved.

Anger or resentment. You feel that you shouldn’t have to do the task or activity, and you’re angry at having to do it. You feel that the world, or some of the people in it, are not treating you fairly. You resent having to do that task or face that situation because of that anger and resentment.

Anger or resentment. You feel that you shouldn’t have to do the task or activity, and you’re angry at having to do it. You feel that the world, or some of the people in it, are not treating you fairly. You resent having to do that task or face that situation because of that anger and resentment.

Any or all of the preceding reasons can stop you in your tracks. If one or more of these dynamics describes you, head to Chapter 10 to find out how you can turn around this “procrastinatory” thinking.

Bite the bullet

If you find that dislike and discomfort are steering you away from doing what you should be doing, see if you can challenge your assumptions. Ask yourself, “Why must I always do the things I like and want to do?” The answer, of course, is that you don’t have to avoid difficulty and discomfort. Just do it! Then ask yourself a second question: “Wouldn’t I be better off putting up with some discomfort and getting it out of the way?” The answer: Absolutely!

Commit to a chunk of time

My son introduced me to this approach. He sets the timer app on his computer to, say, 30 minutes. (Somebody once estimated that 25 to 30 minutes is the optimal attention period for maximum performance.) He commits to working on a project or task for those 30 minutes without stopping, without being distracted. When the alarm beeps, he can stop and take a brief five-minute break. Or, if he feels like he’s on a roll, he can continue working on the task.

Motivate yourself

Sometimes your level of internal motivation doesn’t get you where you need to go. You need external motivation. You can either reward yourself for doing something or penalize yourself for not doing it.

Try the reward approach first. Create your own motivational ladder by coming up with a list of rewards that can motivate you to get the job done. Then rank them in order of their importance to you. For example:

Treat yourself to a mini-vacation.

Treat yourself to a mini-vacation.

Buy yourself something big that you’ve been dying to get but have been denying yourself.

Buy yourself something big that you’ve been dying to get but have been denying yourself.

Treat yourself to a great meal or a dessert.

Treat yourself to a great meal or a dessert.

Go to the movies, see a play, or do something fun.

Go to the movies, see a play, or do something fun.

Buy yourself a small present.

Buy yourself a small present.

However, being nice, even to yourself, doesn’t always cut it. You may respond better to the threat of pain and suffering than to a positive reward. If pain is your thing, try creating a penalty for not completing a task:

Deny yourself a favorite pleasure for a day (TV, a movie, a dessert, going out, and so on).

Deny yourself a favorite pleasure for a day (TV, a movie, a dessert, going out, and so on).

Deny yourself a favorite pleasure for a week.

Deny yourself a favorite pleasure for a week.

Send a donation to a political candidate you dislike.

Send a donation to a political candidate you dislike.

Send cash anonymously to a person you know and dislike. (Make it one week’s salary and I personally guarantee success.)

Send cash anonymously to a person you know and dislike. (Make it one week’s salary and I personally guarantee success.)

Use the smallest reward or penalty that gets the job done. If that doesn’t work, move up to the next reward or penalty on your motivational ladder. Be creative.

To make sure that you do enforce a penalty, tell a friend about your plan and ask him or her to make sure that you follow through. I find that this approach improves your chances of successfully breaking through procrastination. If money is involved, put it in an envelope, address it, put a stamp on it, and give it to a friend, telling him or her to mail it if you don’t come through on your end of the deal.

Go public

Make a public commitment. Tell a good friend about a task that you want to get done and tell him or her when you will complete it. Better yet, tell a bunch of people, perhaps in your next tweet or status update. Be sure to remind that friend or friends to ask you if you have done what you said you would.

Become more selective and assertive

After you identify those activities and tasks that have a lower priority in your life, discover ways to reduce or even eliminate them. For example, social engagements can easily eat up a good deal of your time. You probably attend many engagements out of a sense of obligation or habit. But you don’t have to attend absolutely every party or dinner you’re invited to. Nor do you have to attend every meeting posted by your church, temple, school, or any other organization you’re affiliated with. Go to those events that you truly want to attend, but be selective and assertive. Give yourself permission to say no to many other invitations. You won’t end up being hated by others or ostracized from the community.

Letting Go: Discovering the Joys of Delegating

Remember that old slogan, “If you want something done right, do it yourself”? Yes, it holds some truth. However, by doing it all yourself, you quickly discover that your stress level shoots skyward. Delegating tasks and responsibilities can save you time and spare you a great deal of stress.

You may have a problem delegating for several reasons. Here are some of the more common ones:

You believe that no one else is competent enough to do the task.

You believe that no one else is competent enough to do the task.

You believe that no one else really understands the problem the way you do.

You believe that no one else really understands the problem the way you do.

You believe that no one else is motivated quite the way you are.

You believe that no one else is motivated quite the way you are.

You don’t trust anyone else to be able to manage the responsibilities.

You don’t trust anyone else to be able to manage the responsibilities.

All these reasons can hold some truth. But in many cases, these reasons aren’t accurate at all. The reality is that other people can be taught. You may be pleasantly surprised by the level of work others can bring to a task or responsibility.

The fine art of delegating

You may be from the “Do this, and have it on my desk by tomorrow morning!” school of delegating. Here are some tips to help you delegate more effectively:

Find the right person. Make sure that your delegatees have the knowledge and skills to do the tasks asked of them. And if you can’t find a person who has the knowledge and skills, consider investing the time in training someone. In the longer run, you’ll be ahead of the game.

Find the right person. Make sure that your delegatees have the knowledge and skills to do the tasks asked of them. And if you can’t find a person who has the knowledge and skills, consider investing the time in training someone. In the longer run, you’ll be ahead of the game.

Package your request for help in positive terms. Tell the person why you selected him or her. Offer a genuine compliment reflecting that you recognize some ability or competence that makes that person right for the job.

Package your request for help in positive terms. Tell the person why you selected him or her. Offer a genuine compliment reflecting that you recognize some ability or competence that makes that person right for the job.

Be appreciative of that person’s time. Recognize that you’re aware that the person has his or her own work to do, but that you would really be grateful if he or she could help you with this task.

Be appreciative of that person’s time. Recognize that you’re aware that the person has his or her own work to do, but that you would really be grateful if he or she could help you with this task.

Don’t micro-manage. After you assign a task and carefully explain what needs to be done, let the person do it. Keep your hands off unless you clearly see that things are taking a wrong turn.

Don’t micro-manage. After you assign a task and carefully explain what needs to be done, let the person do it. Keep your hands off unless you clearly see that things are taking a wrong turn.

Reward the effort. If the person does a good job, say so. And if he or she doesn’t do it quite the way you would have but still put a lot of effort into the task, let him or her know that you appreciate the effort.

Reward the effort. If the person does a good job, say so. And if he or she doesn’t do it quite the way you would have but still put a lot of effort into the task, let him or her know that you appreciate the effort.

Delegating begins at home

You may associate the word delegating with working in an office and handing off a project to an associate or assistant. However, delegating tasks and duties at home is a major way to save a lot of time. Here are some suggestions:

Let one and all share in the fun. Everyone in the family (assuming that he or she is old enough to walk and talk) can, and should, have a role in sharing household duties and responsibilities.

Let one and all share in the fun. Everyone in the family (assuming that he or she is old enough to walk and talk) can, and should, have a role in sharing household duties and responsibilities.

Start with a list. Divvy up those less-desirable chores, such as washing dishes (or putting them in the dishwasher), doing laundry, cleaning up bedrooms, taking out the trash, and emptying the dishwasher.

Start with a list. Divvy up those less-desirable chores, such as washing dishes (or putting them in the dishwasher), doing laundry, cleaning up bedrooms, taking out the trash, and emptying the dishwasher.

Start small. Don’t overwhelm your family right off the bat. Give them one or two assignments and then add on as appropriate.

Start small. Don’t overwhelm your family right off the bat. Give them one or two assignments and then add on as appropriate.

Don’t feel guilty. In the long run, your family will come to value the experience. (Recognize that it may be a very long run, however.)

Don’t feel guilty. In the long run, your family will come to value the experience. (Recognize that it may be a very long run, however.)

Buying Time

You may subscribe to the old work ethic, “Never pay anyone to do something that you can readily do yourself.” This is a mistake. Hiring someone to help you can give you more time for the things you want to do and, in the process, make your life simpler and less stressful.

Am I being casual about your finances? I don’t think so. I realize that you may not have a lot of extra money in your pocket. However, gone are the days when only the rich hired other people to help them out. Sometimes hiring someone else is clearly wise.

Here are some questions to help you decide whether hiring someone else or paying for a service makes sense:

What chores do I absolutely hate?

What chores do I absolutely hate?

Which chores constantly provoke a battle between me and my spouse or me and my roommate?

Which chores constantly provoke a battle between me and my spouse or me and my roommate?

What chores do I merely dislike doing?

What chores do I merely dislike doing?

What chores do I not do very well?

What chores do I not do very well?

What chores do I not mind doing, but really aren’t worth my time and effort?

What chores do I not mind doing, but really aren’t worth my time and effort?

Tasks that you may want someone else to do for you include cleaning, doing laundry, grocery shopping, painting, handling pet care, mowing the lawn, and so on.

Avoid paying top dollar

Getting someone else to do less-than-desirable chores need not cost you a bundle. You probably don’t need an expensive professional. Lots of people who are “between opportunities” will be willing to do chores for you if you pay them. Go online. A number of Internet services can match you up with someone who is willing to help you out (for a fee, of course). Friends on social-networking sites can also be a source of referrals. Don’t rule out non-digital sources — supermarket billboards, neighborhood circulars, or your local newspaper. (When you find someone, be sure to check his or her references.) And don’t overlook high-school and college students. Schools often have an “employment-wanted” service, especially during the summer months. These students can be cheaper and surprisingly reliable.

Realistically assess your financial ability to hire someone to do a few or many of the items on your list. Remember, too, that the emotional relief and the extra time you gain are well worth the money in many cases. Spend the bucks.

Strive for deliverance

These days, many of the things you need can be delivered. If you live in a good-sized city, almost everything can be delivered. You can save time by dialing the right series of digits or clicking the right places on the Internet. In addition to take-out food, items that you can have delivered to your door include the following:

Groceries

Groceries

Clean laundry

Clean laundry

DVDs

DVDs

Meats from the butcher

Meats from the butcher

Sweets from the bakery

Sweets from the bakery

Liquor from the liquor store

Liquor from the liquor store

Books

Books

Actually, just about everything

Actually, just about everything

Effective time management is really all about managing your priorities. The trick is figuring out what those priorities are and making time for them to happen. Remember those wise words of Bertrand Russell: “

Effective time management is really all about managing your priorities. The trick is figuring out what those priorities are and making time for them to happen. Remember those wise words of Bertrand Russell: “ Maybe you don’t experience time-related stress. Let’s find out. Take a look at the following list and check off those items that seem to describe you:

Maybe you don’t experience time-related stress. Let’s find out. Take a look at the following list and check off those items that seem to describe you: