“LIFE IS HARD INDEED; the way has many branches” (人生實難,大道多歧). In his last years Tai Jingnong 臺靜農 (1902–1990), literary historian, fiction writer, poet, and calligrapher, liked to cite this saying in his talks, essays, and calligraphic works.1 Simple as it appears, the statement contains rich classical allusions. The first part, “life is hard indeed,” originated with the Zuozhuan 左傳,2 although it is more often associated with Tao Qian 陶潛 (365?–427); in “Zijiwen” 自祭文 (An essay of self-obituary), he summarizes the precarious nature of human life with this statement.3 Wang Can 王粲 (177–217), one of the “Seven Talents of the Jian’an Era (196–220),” also used the phrase when deploring the evanescence of life and the inevitable dissolution of any attachment.4

The second part, “the way has many branches,” is derived from a fable in the Liezi 列子 about a massive search for a missing goat, which leads all the searchers astray as they step onto endlessly forked paths. Hence the moral that “one loses the goal (the goat) as a result of the multiple branches of the Way” (大道以多歧亡羊).5 Tai Jingnong may well have had another story in mind too. Ruan Ji 阮籍 (210–263), one of the “Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove” (Zhulin qixian 竹林七賢) of the Wei era (220–265), is said to have often ridden an oxcart on excursions. He let the ox take him onto any path at its will; whenever his cart reached a dead end, he burst into profuse tears and turned back.6

Looking back at his own life, which was full of erratic adventures and unexpected sidetracks, Tai Jingnong had good reason to invest deep feeling in the quoted expression. A native of Anhui, Tai belonged to the May Fourth generation aspiring for cultural reform and national rejuvenation through literature. He came to know Lu Xun in 1925 and was later involved in leftist activities, being one of the founders of the Northern Chinese League of Leftist Writers (Beifang zuolian 北方左聯) in 1930.7 For his alleged subversive activity against the Nationalist regime, Tai was arrested three times between 1928 and 1934.8 During the Second Sino-Japanese War, he took refuge in Sichuan, where by chance he met Chen Duxiu 陳獨秀 (1879–1942), forerunner of the May Fourth Movement and the Chinese Communist Revolution.9 In 1946, Tai took a short-term teaching appointment at National Taiwan University. But the outbreak of civil war in 1949 blocked his way home, turning his sojourn on the island into a permanent stay.

Given his checkered political record, it is not difficult to imagine Tai Jingnong’s misgivings during the early years of Nationalist rule in Taiwan. That he tried to find solace in figures such as Tao Qian and Ruan Jin, both witnesses to a tumultuous time in medieval China, the Wei-Jin era (220–420), perhaps bespeaks an attempt to reconcile himself with the present in the light of history. Closer reading of Tai’s favorite saying points to even darker subtexts. In Tao Qian’s “Essay of Self-Obituary,” “Life is hard indeed” is followed by the question, “Can death offer a solution?” (siruzhihe 死如之何), and in the Liezi fable of the missing goat, the statement “One loses the goal as a result of the multiple branches of the Way” leads to the observation that “one loses his life (or active nature) as a result of the various directions of his learning” (xuezhe yi duofang sangsheng 學者以多方喪生).10

But the story of Tai Jingnong would not be so intriguing were it only about atrocity and death, leitmotifs that characterize the writing and lived experience of most literati of his generation. What distinguishes Tai’s case is his conversion from literature to calligraphy midway through his career. He won acclaim in the mid-1920s first as a realist fiction writer but did not reach his full creative power until he established himself as a calligrapher, after relocating to Taiwan. Thus Tai exhibits a peculiar politics and aesthetics of writing. Whereas he spent the first part of his career fathoming the “depths” beneath the surface of Chinese life, he directed the second part of his career to the “surface” of writing, the lines and strokes that constitute Chinese characters.

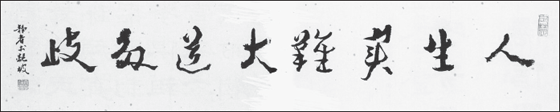

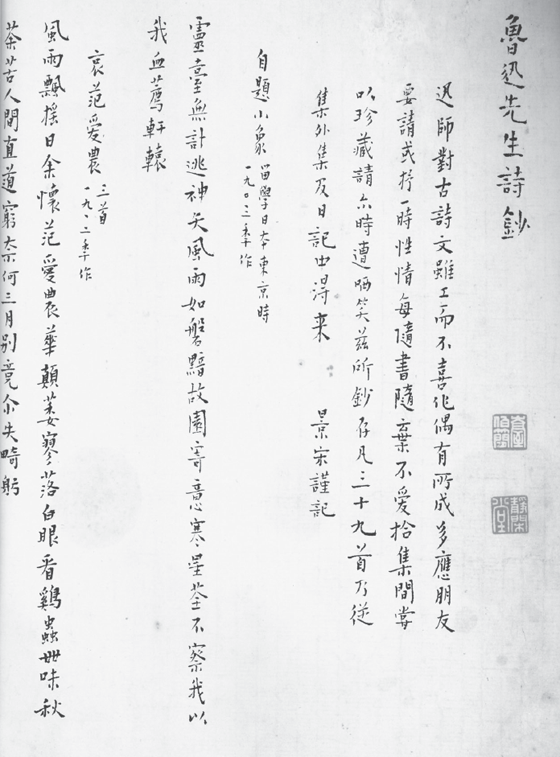

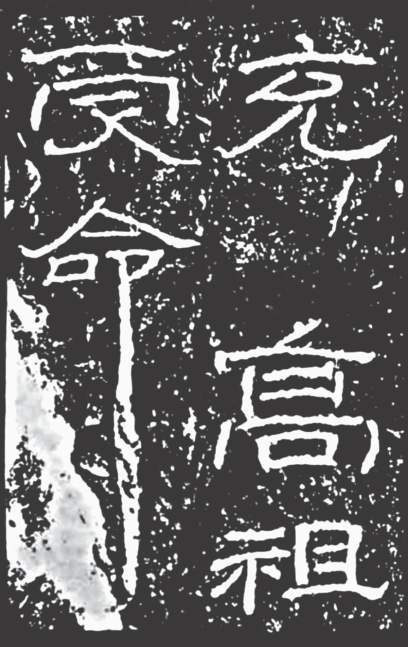

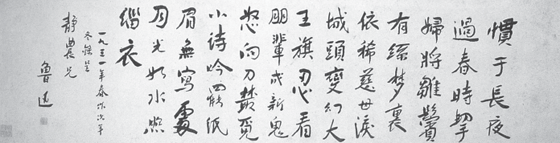

“Life is hard indeed; the way has many branches.” –Tai Jingnong. Courtesy of Ms. Feng Yeh

Tai’s transformation of course had to do with his political discretion, required by the 1949 divide. Nevertheless, a more compelling reason perhaps was that national and personal trials had led him to a different understanding of artistic agency and historical representation. By deferring literature to focus on calligraphy, he may not have resorted to a more conventional, and therefore safer, craftsmanship, as common wisdom would have it, but to a polemical vocation: whereas writing betrays its finitude, the characters drawn on the paper open up new imaginary possibilities.

Thus, as his scroll “Life is hard indeed; the way has many branches” indicates,11 Tai Jingnong registered his pathos about life forever beset by uncertainties, even after death; yet the brushwork of the eight Chinese characters demonstrates vigor and tenacity, as if the calligrapher were struggling to square his emotion with the meaning imposed by the characters. A dynamics of interpretation is created when the reader/viewer shifts between what the characters imply and how they are being displayed. Granting the strong auto-elegiac connotation of the scroll, the calligrapher appears to assert a creative force, however momentary, through his rugged lines and forceful strokes. He seems to be searching for a style with which to ruminate on the meaning of life in the shadow of death. And above all, Tao Qian and Ruan Ji, the two Wei-Jin figures Tai Jingnong identified with through the expression on the scroll, are best remembered not because of the harsh life they had been through but because of the poetic or idiosyncratic style of life they each posited, nay, created, against adversities.

Rescuing Poetry from History

Tai Jingnong started his literary career as a poet. In early 1922 he published in a Shanghai newspaper, Minguo ribao 民國日報 (National republic daily), “Baodao” 寶刀 (Precious knife), which starts:

Run out the hot blood of youth,

wipe out the devils of the world.

When the hot blood runs no more,

the seeds of the devil grow.

When the devil is destroyed,

bloody flowers blossom!

……

My precious dagger—

is the love of my life,

handed down by my ancestors,

because the devil is also my ancestors’ enemy!12

流盡了少年的熱血,

殲盡了人間的惡魔,

熱血流盡了,

惡魔的種子生長了,

惡魔殲盡了,

血紅的鮮花開放了!

…

我小小的寶刀

是我生命的情人

他是我祖先留下的,

因爲惡魔也是我祖先的仇人!

With typical May Fourth revolutionary fervor, Tai Jingnong writes here about his desire to battle “the devils of the world” at the price of bloodshed. The combined images of youth and death wish foreground the sentiment of adolescent martyrdom, which will let “bloody flowers blossom.”

At the time, Tai Jingnong was still a high school student in Hankou, where he was involved in a series of campaigns in the name of the May Fourth Movement. Later in 1922 he moved to Beijing and enrolled at Peking University. He quickly became one of the founders of the Tomorrow Society (Mingtian she 明天社), the third national organization focused on modern literature after May Fourth.13 In 1925, Tai Jingnong met Lu Xun, and they quickly formed a firm friendship. Together with four other friends,14 they founded the Unnamed Society (Weiming she 未名社), promoting foreign literature, particularly Soviet literature, in translation. Meanwhile, Tai edited Guanyu Lu Xun jiqi zhuzuo 關於魯迅及其著作 (On Lu Xun and his works, 1926), the first collection of critical essays on Lu Xun. It was at this time that Tai Jingnong took a leftist turn in politics. He and several friends called for founding the League of Leftist Writers of Northern China in the fall of 1930, and he was appointed a member of the Standing Committee when the league was established in early 1931. Under his aegis, Lu Xun was able to return to Beijing in 1932, giving the famous “Five Talks” and attending two underground forums, without being harassed by local authorities.15 Tai’s close ties with Lu Xun can also be seen in their frequent correspondence during this time as well as Tai’s lectures and essays on the master.16

Tai Jingnong’s literary works reflect Lu Xun’s influence. In the poem “Qingni” 請你 (Would you please, 1926), for instance, he writes

Would you please not spare

the gift of the precious dagger and poison;

I don’t want to speak of joy again

because my joy has been given away to this emptiness!

Would you please not remember

the bitter and miserable past;

I don’t want to have a future

because my future will be just as same as my past!17

請你不要吝惜

寶刀和毒藥的施與;

我不願再説歡欣

因爲我的歡欣都交付在這虛空裏

請你不要記憶

酸辛和淒楚的過去;

我不願再有將來

因爲我的將來依然如同我的過去!

The poem smacks of the ambiguous tone and paradoxical logic of Lu Xun’s prose poetry collection Yecao 野草 (Wild grass, 1927), produced almost at the same time. Like the master, Tai Jingnong finds joy in nihilism and treats the future only as a bitter return to the past. The interlocutory structure between the speaker and the addressee promises no communication but is underlain by four negative promptings (buyao 不要). And yet the poet renders his rejection in an inviting tone of qing 請 (please). More striking is the image of “precious dagger,” which in Tai’s earlier poem cited above refers to a weapon used to kill the enemy; now it is invoked as a tool to terminate the poet’s own life. Thus there arise multiple paradoxes between hope and despair, hospitality and hostility, self and other, lethal joy and palatable death wish.

Tai Jingnong’s talent lay more in fiction writing. His first piece, “Shoushang de niao” 受傷的鳥 (A wounded bird, 1924), a story of unrequited love, is full of Wertherian sentimentalism, but the truncated aerial image of the “wounded bird” would in many ways become the leitmotif of his career in the years to come. Tai’s style underwent a noticeable change as a result of his apprenticeship with Lu Xun. Between 1928 and 1930 he published two collections of short stories, titled Dizhizi 地之子 (Sons of the earth, 1928) and Jiantazhe 建塔者 (Tower builders, 1930). Whereas Sons of the Earth describes Chinese peasants as earthbound creatures trapped in the cycle of misery and inertia, Tower Builders highlights young revolutionaries who aspire to a lofty goal at the cost of their own lives. Together they point to two fictional trends of the time: nativist realism and revolutionary romance.

Shuttling between his “earth” and “tower,” Tai Jingnong wrote some of the best stories of 1920s China. His bent for rhetorical economy, mixing irony and melancholy, and meditation on the agency of writing all recall Lu Xun’s writing. In “Tian erge” 天二哥 (Second brother Tian), a country ne’er-do-well behaves just like Ah Q, cowering before the powerful and bullying the weak as a method of obtaining “spiritual victory.” In “Qiying” 棄嬰 (A abandoned baby), the narrator suffers from a guilty conscience after realizing that an abandoned baby died as a result of his hesitation to make a timely rescue;18 he thus reenacts the dilemma of Lu Xun’s noncommittal narrators in stories such as “Guxiang” 故鄉 (My old home) and “Zhufu” 祝福 (New year’s sacrifice). A similar case can be found in “Weibi zhufu” 為彼祝福 (God bless you), about an old itinerant worker who, having been deprived of everything, finds unlikely solace in the church at the end of his life. In his edited anthology of modern Chinese literature (Xiandai zhongguo xinwenxue daxi 現代中國新文學大系 [A compendium of modern Chinese literature]), Lu Xun features four of Tai’s stories, more than from any other writer.19

More noteworthy are the stories where Tai Jingnong shows a different take on Lu Xunesque style. In “Hongdeng” 紅燈 (Red lantern), a poor old widow learns that her sole son has been arrested and executed after a failed robbery attempt. Unable to put together even a humble funeral, the sorrowful mother finds some remnants of red paper left by her son and uses it to make “a beautiful, tiny lantern”; “her heart is filled with both pain and pleasure upon “accomplishing the grand task” by herself.20 On the evening of the Ghost Festival, she floats the red lantern on the river in accordance with the local custom of pacifying the dead, and she seems to see her son “being redeemed, moving away in a red dress, which looks beautiful, under the guidance of the red lantern.”21 In “Baitang” 拜堂 (Wedding ceremony), a poor peasant is marrying his widowed sister-in-law, already pregnant with his baby. Out of shame, they hold the wedding at midnight, with only two female witnesses in attendance. Impoverished circumstances do not keep the bride from adding a celebratory touch to her dress. But she cannot not help breaking into tears when asked to kowtow to the ghost of her first husband. “We need a good omen after all, for our own lives,” murmurs one witness.22

Despite their predicaments, these characters struggle to make sense of their suffering, above all by observing religious rituals and local customs. These formalities can be taken as exposing Chinese peasants’ superstition or stubbornness, but under Tai’s treatment they appear to dramatize less his characters’ idées fixes than their willful efforts to make do with the destitution of life. Whenever given a chance, Tai’s characters can create something against all odds, and at their most imaginative they call forth the “poesis”—in the classical sense of “making” poetry of something ordinary—of a world that otherwise would not have been worth living in. Both characters discussed above have been denied proper ceremonial observances. Nevertheless, they manage to accomplish their wishes, through either a tiny self-made lantern or a clandestine wedding, thus asserting their tact, if not tactics, in coping with communal strictures. When the mourning mother floats her lantern on the river and the peasant couple ties their knot at midnight, they can claim an abject triumph vis-à-vis reality.

Whereas Lu Xun is torn by the despair that besets his characters,23 Tai Jingnong appears more ready to lend options to his “sons of the earth.” In so doing he does not indulge a naïve humanist plea or an ironic sympathy; rather, he seems to propose that, instead of serving as mere specimens of cannibalism for enlightened writers, social underdogs are entitled to dream their own dreams and act out their own logic, however humble. Writing, reactionary and revolutionary alike, need not be a reflection of sociopolitical determinism any more than a recognition of individual longing and creativity. Yue Hengjun 樂蘅軍 has described Tai Jingnong’s stories as demonstrating in this sense “a heart of mercy” (beixin 悲心)—with a Buddhist reference to the writer’s all-embracing capacity before the trials of the human world.24

NEVERTHELESS, THIS “HEART OF MERCY” would soon be overridden by a “heart of wrath” (fenxin 憤心).25 Tai Jingnong’s Tower Builders introduces a group of young revolutionaries who suffer from merciless coercion and self-inflicted melancholia in a dark political time. In the title story, “Tower Builders,” a young woman revolutionary walks with her comrades to the execution ground chanting, “To build a tower, blood is in order.”26 In “Sishi de huixing” 死室的彗星 (Comet in the house of death), the brutally tortured revolutionaries are yearning for martyrdom so as to complete their vocation. The narrative of these stories is fragmentary in structure and elliptical in tonality, as if the truth could never be fully spelled out; the narrator appears like someone who has just returned from the scene of death to pass on the message of the unspeakable. Tai Jingnong writes in the afterword to the collection, “The characters in this volume are mostly prophets of our time. But my pen could hardly touch the depth of their souls who had found their abodes on the cross. My heart hurts. As a melancholy writer wandering amid ruins and desolate tombs, where could I find the strength to paint the light of the time?”27 He could only write to call on the “ghosts of the spring night,” as hinted by the title of “Chunye de youling” (春夜的幽靈), while turning his own narrative stance into that of a ghostly mourner.

While the shift from Sons of the Earth to Tower Builders, or from a “heart of mercy” to a “heart of wrath,” reflects the changing political and cultural circumstances between 1928 and 1930, it is underlined by a personal incident. In early 1928, Beijing authorities shut down the Unnamed Society for publishing Leon Trotsky’s Literature and Revolution; a few months later, they arrested Tai Jingnong and the two translators of Trotsky’s book, Wei Congwu韋叢蕪 (1905–1978) and Li Jiye 李霽野 (1904–1997), on the charge of disseminating leftist thought. Tai was imprisoned for fifty days and, at least for a while, his case “was rather ominous.”28 Thus there is good reason to surmise that Tai’s stories about the jailed revolutionaries were based on his own experience, and that his changed mood and style in Tower Builders resulted from a close encounter with the threat of death.

Tai Jingnong’s imprisonment marked only the beginning of his political trials, however. In late 1932, he was again arrested for allegedly keeping revolutionary materials and a bomb.29 Although both charges were dropped weeks later, Tai had lost his teaching position at Fu-jen Catholic University. A year and a half later (July 1934), he was jailed a third time and the charge remained the same, that he was a fellow traveler of the Communist Party.30 After his release in early 1935, Tai saw that it was unlikely he would find any position in Beijing. He headed south and took short-term teaching jobs in Fujian and Shangdong provinces in the following two years. The three jail experiences left a traumatic imprint; although Tai remained reticent about them for the rest of his life, they constitute the dark, elusive core of his literary and artistic works.

Tai Jingnong’s revolutionaries do not convey the Promethean heroism of Lu Xun’s martyrs, as in “Yao” 葯 (Medicine); nor do they demonstrate the solipsistic theatrics that characterize the trendy “revolution plus romance” fiction, such as Jiang Guangci’s 蔣光慈 (1900–1931) Yeji 野祭 (Memorial service in the wilderness). Rather, they are sullen figures whose will and energy have been thwarted prematurely; like “comets” or “ghosts,” they can take shape only in phantasmal traces. If “tower builders” promise solidarity and eternity, “comets” and “ghosts” betray the phantasmagoric nature of such an agency. Or by corollary, if “tower builders” are meant to be the forces that elevate the “sons of the earth” to the height of heavenly plenitude, “comets” and “ghosts” point to their spectacular fall into death and posterity.

Nevertheless, even when confined to the “house of death,” Tai was able to conjure up a space of his own, thus achieving an imaginary flight out of stifling incarceration. This imaginary flight is found not in his fiction but in his poetry. “Yuzhong jian luohua” 獄中見落花 (Seeing a fallen blossom in jail, 1929) is a poem Tai wrote while in jail.

Silently I pick the flower petals,

piously I throw them into the sky;

and I plead in a murmur;

“Please fly to her window,

tell her someone is captured by loneliness!”

The flower petals fall sadly to the ground,

as if they are unwilling to fly again;

and I ask again quietly:

“Are you from where she is,

is she sobbing alone at the window?”31

我悄悄地將花瓣拾起,

虔誠地向天空抛去;

於是我叮嚀地祈求:

“請飛到伊的窗前,

報道有人幽寂!”

花瓣淒然落地,

好像不願重行飛去;

於是我又低聲痴問:

“是否從伊處飛來,

伊孤獨地在窗前哭泣?”

The poem unfolds along a contrast of images, between the deadly pressure of prison and the delicate frailty of fallen flowers, claustrophobic fear and imaginary escape, the incarcerated poet and his beloved in longing. At the center are the fallen flower petals, which suggest love and hope as well as their denial. The poet throws the petals into the sky, wishing them to carry his romantic yearnings beyond the jail, but in vain: they only fall to the ground.

The inevitable, second descent of the fallen flowers is a poignant reminder of the Sisyphean stance of Tai Jingnong as a poet and a revolutionary. He seems to ask: Once cut off, could his political and romantic passion flower again? This brings us to the image that inaugurated Tai Jingnong’s creative writing in 1924. “A Wounded Bird” ends with the statement, “I am a wounded bird, carrying with me an arrow, pain, and blood. Without any strength, will I be able to fly toward the dismal sky?”32 As a wounded bird, a failed tower builder, or a fallen flower, Tai Jingnong’s poetic subjectivity is wrought with an Icarus-like destiny, its aerial hope doomed to be dashed in an inevitable fall.

Still, the parabolic path of the fallen flowers enacts the poet’s momentary leap of faith, even transforming his monologue into an imaginary dialogue. In a way, just like the old woman in “Red Lantern” who makes a small lantern to commemorate her son, thus rekindling hope for her life, Tai Jingnong “invents” a circuit of emotional movement through his encounter with the fallen flowers. The evocative power of poetic imagery opens a “window,” as suggested by the poem, to the world beyond the prison house of body and language. Moreover, in the incantation of “fallen flowers,” one of the most popular themes of classical poetry, he is echoing a wide range of expressions about love and dejection, loneliness and nostalgia, uttered by Chinese poets from Wang Wei 王維 to Li Bai and from Du Fu to Li Yu 李煜.33 Through this reverberation across time, Tai Jingnong demonstrates an intriguing aspect of his revolutionary literature: that an iconoclastic impulse can be conveyed in traditional sentiment, and that political volition can reveal a delicate, lyrical heart.

WHEN THE SECOND SINO-JAPANESE WAR broke out in the summer of 1937, Tai Jingnong joined the national exodus to the hinterland. He ended up in Jiangjin, Sichuan, where he served first as an editor at the National Compilation and Translation Bureau and then as a professor at the National Women’s Normal College. His political utopianism may have worn off after years of instability—imprisonment, exile, and the death of a brother en route to Sichuan—but a recalcitrant passion must still have survived somewhere in him. In fall 1938, Tai Jingong had a chance meeting with Chen Duxiu, who likewise was taking refuge in Jiangjin.34 Almost a déjà-vu, the meeting reenacted Tai’s experience of connecting with Lu Xun in the mid-twenties, and it had profound meaning for his later career. A forerunner of the May Fourth Movement and a founder of the Chinese Communist Party, Chen is one of the most prominent figures in early Chinese Communist history. He eventually was labeled a Trotskyist and expelled by the Party. When Tai came to know him, Chen Duxiu was already a poor and feeble man, released from a Nationalist prison. The two quickly found in each other a kindred spirit. Both had been practitioners of a forbidden idealism—“tower builders”—and both had fallen prematurely from the edifice of revolution. Driven by the war to a small town from where their enthusiasm had once soared high, they were “wounded birds,” so to speak, seeking remnants of warmth in each other’s company.

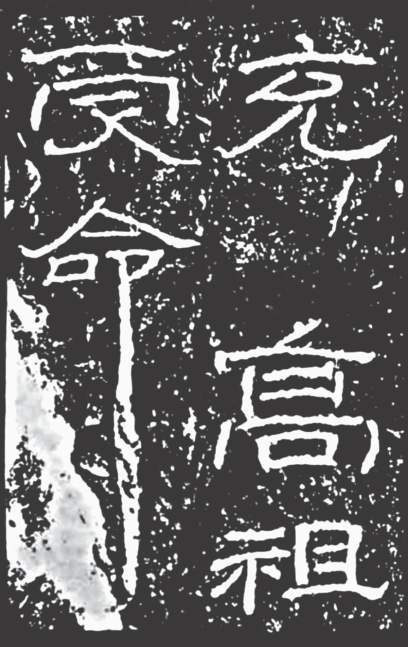

At this time, Tai Jingnong’s literary style changed again. He wrote a series of essays and stories decrying Japanese aggression; his tone was strident and his intent patriotic.35 Meanwhile, he was privately engaged in writing a novella, Wangming jiangshi 亡明講史 (The saga of the fall of the Ming). Still unpublished,36 it chronicles the events around the end of the Ming dynasty: the fall of Beijing into the hands of Li Zicheng 李自成 (1606–1645), the massive surrender of Ming officials, the suicide of Emperor Chongzhen 崇禎 (1611–1644), the massacres by rioters as well as the Manchus, the founding of the Southern Ming in Nanjing, the rise and fall of local insurrections against the Qing, the sacrifice of generals such as Shi Kefa 史可法 (1602–1645), and the court intrigues and corruption of the Southern Ming. The novella culminates in the fall of Nanjing and the capture of Emperor Hongguang 弘光 (1607–1646) by Qing troops.

At a time when China was waging a war of resistance against Japan, a work about the fall of the Ming to the Manchus easily suggests a parallel between the fates of the Ming Empire and Republican China. Tai Jingnong makes no attempt to conceal the analogy. Written in anticipation of the three hundredth anniversary of the fall of the Ming (1644–1944), his novella promotes a pessimistic outlook on the wartime Nationalist government, which he believed was in total dysfunction. Its dubious national allegory aside, The Saga of the Fall of the Ming makes a suspect case even at a rhetorical level, because it does not read like a historical saga by any conventional standard. For all the heavy, mournful aspects of dynastic cataclysm, the story unfolds in a light-hearted, even facetious tone, as if the narrator were relishing the demise of the Ming as a lugubrious farce. When emperors and invaders, courtiers and bandits all look like bigots, clowns, or imposters, then riots, battles, and even massacres seem little more than a cheap parade of bloodied circus villains. When history manifests itself as an outburst of irrationalities, the select few positive figures, such as Shi Kefa, simply appear like absurd heroes.

If Tai Jingnong’s earlier writings demonstrate his “heart of mercy” or “heart of wrath,” a work like The Saga of the Fall of the Ming points to a cynicism able to laugh away any values. Where Tai’s mercy and wrath come from his view of history as a flux of moral options, worthy of affective and political commitments, his cynicism casts doubt on any effort to change the set course of human follies. History under this view does not confer ontological prestige, and the present may appear to be a repetition of the past, or vice versa. As a result, one feels the same unbearable lightness of being in reading either about General Shi Kefa’s tragic defense of Yangzhou, which led to the bloodiest massacre after the city fell, or about Emperor Hongguang’s wanton revelry right up to the last days of his rule. In all this, Tai Jingnong’s frivolous style recalls Lu Xun’s Gushi xinbian 故事新編 (Old stories retold, 1935).37 Both employ anachronism—a mismatch of temporalities—as a way to subvert historical rationale, and both question the feasibility of (poetic) justice in the making of a grand narrative. At its most radical, their cynical humor helps unleash an anarchistic impulse, threatening to bring down any and all truth claims.

The Saga of the Fall of the Ming was written at the height of the war, and must have been completed no later than 1942, because Chen Duxiu had a chance to read it before he passed away in late May that year. In a letter to Tai Jingnong, Chen urged that Tai “try [his] best to revise [the novella], turning it from fiction into history, for historical fiction such as Lieguo 列國 [A chronicle of the kingdoms during the reign of the Eastern Zhou] and Sanguo 三國 [A romance of three kingdoms] after all becomes of no value when judged either as fiction or as history.”38 Chen’s comment may have influenced Tai Jingnong’s decision not to bring his novella to publication, but more crucially, it foregrounds the difference of opinion between the two men regarding the intelligibility of history. For Chen, history should possess a sacred power validating the meaningfulness of human engagement, which, in his case, is the project of nation-building; for Tai, however, precisely because history has lost such power, fiction, particularly in the vein of Old Stories Retold, has to be brought to bear on the “unrepresentability” of history. In other words, disillusioned by the ongoing discourse of narrating nation as history,39 Tai finds in fiction something in service of not nation but the dissemination of a negative dialectic.40

The Saga of the Fall of the Ming stands for only one end of the spectrum of Tai Jingnong’s literary engagements during wartime. At the opposite end, he was rising as a classical-style poet. That modern Chinese writers from Lu Xun to Yu Dafu and Guo Moruo were all capable of writing classical-style poetry despite their antitraditionalist stance is a subject deserving a full treatment in its own right. For our purpose, it is noteworthy that Tai took up classical poetry, a skill he acquired from traditional education in childhood, in the middle of writing his farcical saga of the late Ming. In sharp contrast to the cynical tone of his fiction, his poems showcase a melancholy mind during a turbulent time. For example, “Yeqi” 夜起 (Rising at night):

The immense cosmos sinks deep like a dream,

the desolate darkness cannot keep one from getting up at night.

Facing the wilderness, reciting the “Mountain Ghost,”

all of a sudden, a shocked bird flutters out of the cold woods.41

大圜如夢自沉沉,

冥漠難摧夜起心;

起向荒原唱山鬼,

驟驚一鳥出寒林。

The first two lines constitute a wild and gothic landscape that may also project the poet’s mindscape. Unable to sleep, the poet gets up to recite the “Mountain Ghost” (Shangui 山鬼), a chapter from Qu Yuan’s 屈原 Jiuge 九歌 (Nine songs), thereby echoing the sighs of the arch-lyrical poet of two thousand years ago who, in the persona of a longing girl, deplored his betrayal by his beloved and his sense of loss. The poet’s singing disturbs the nocturnal quietude, then is answered by a lonely bird’s sudden thrust out of the woods. A sense of precariousness permeates the poem, culminating in the bird’s abrupt motion. Why is the bird so restless and vigilant at night? Is it still the “wounded bird” from Tai’s early days?

Tai Jingnong’s best classical-style poems were mostly occasioned by his quotidian life in Jiangjin. He writes about pawning family clothes for food (“Dianyi” 典衣 [Pawn clothes], “Yexing” 夜行 [Night walk]), the muddy road he had to tramp on daily (“Nitu” 泥途 [Muddy journey]), an abject celebration of the Moon Festival (“Bingyin zhongqiu” 丙寅中秋 [The Moon Festival of the bingyin year]), and friends he had long lost contact with (“Ji qiumengan guiyang” 記秋夢盫貴陽 [For autumn dream studio in Guiyang]).42 Behind these subjects, there is always a poet brooding over the vicissitudes of life and the sense of wasted time and remote hope:

I ask Heaven but gain no answer, and I find myself drained of poetic words,

I have wasted my feeling over drinking, and my sideburns are showing silky lines.

In a whole cold mountain there goes only one traveler,

bestowed on south-facing branches is a profusion of songs and tears.43

問天不語騷難賦,

對酒空憐鬢有絲。

一片寒山成獨往,

堂堂歌哭寄南枝。

The harsh time drives the poet to ponder the meaning of existence while experiencing the first physical sign of aging. He then seeks solace in the natural scenery of a wintry mountain and plum blossoms. Upon second reading, this scenery turns out to be a coded cultural landscape: “cold mountain” is synonymous with the Tang monk poet Cold Mountain (Hanshan 寒山, after 584–before 704), and “south-facing branches” refers to both the image in Gushi shijiu shou 古詩十九首 (Nineteen old poems)44 and the painting of plum blossoms, “Nanzhi zaochuntu” 南枝早春圖 (South-facing branches in early spring), by the Yuan hermetic painter Wang Mian 王冕 (?–1359). Having realized the vacuity of life, the poet turns to nature. But this nature becomes accessible only through either religious solitude or social seclusion; its meaning is mediated by either poetry or artwork.

Tai Jingnong’s exercise of classical-style poetry may appear to be a leap backward from his early, radical days, but perhaps he was entertaining a different but equally radical agenda. With his vernacular fiction and poetry, Tai had best exemplified the “obsession with China,” in C. T. Hsia’s terminology, that characterizes the discourse of modern Chinese literature.45 This discourse equates modernity with nation building and literature with social commitment, and it generated the campaigns from literary revolution to revolutionary literature. For political as well as personal reasons, Tai Jingnong seems to have reached by the late thirties a point where neither “calls to arms” nor “wandering” could fully express his sentiments, and his cynical tone in The Saga of the Fall of the Ming signaled his crisis. Beyond the prescribed forms of modern literature, he sought via classical-style poetry a form to channel his sentiments, which were too complex to be contained by the formula “obsession with China.”

In other words, though a gesture of cultural nostalgia, Tai Jingnong’s poetic endeavor brought about an alternative engagement with Chinese modernity. The elaborate conventions and rich allusions of classical-style poetry provided a network of references through which he tried to re-orient himself vis-à-vis a civilization shattered by war. In answer to those who consider him an escapist from his early commitments, Tai could have argued that classical-style poetry “liberated” him from the bondage of national and revolutionary determinisms, throwing him into a realm where historical contingencies and individual choices, heroic deeds and collective catastrophes have left endless traces for reflection. At its most polemical, this “liberation” through classical-style poetry takes on an existential dimension, in the sense that it discloses to the poet a threateningly vast zone of temporalities, demanding that he make sense of the amorphous constellation of the past and present. Tai’s “Quzhu” 去住 (Leave or stay), written in early 1946, is a good case in point.

To leave or not to leave, a hard decision indeed,

to stay or not to stay, what is all this for?

The sage deplored: the capture of the unicorn should harm the Way,46

the dog butcher rejoiced: his humble origin should earn him a noble reward.47

The moon sets, thousands of mountains cast in the dark,

autumn wind blows, the wilderness embraced by the fall.

Clouds in the sky fold and unfold,

long sword reflects the radiant eyes.48

去住難為計,

棲遑何所求。

獲麟傷大道,

屠狗喜封侯。

月落千山墨,

商飆四野秋。

天雲看舒卷,

長劍照雙眸。

This is a poetic meditation on time and timing. At the surface level, the end of the war does not bring the poet joy but a dilemma about future prospects. This quandary quickly takes on a historical dimension. At a difficult point, the timing of things could be so skewed that a good omen (the capture of the unicorn) proves to be a curse and, by contrast, an unworthy deed (dog butchering) could be rewarded with honor. The poet wonders if he has missed his best time and if he can still make any right decision at a historical juncture bereft of logic. To that extent he finds himself caught in a predicament that could be as much modernist tribulation as a perennial dilemma of humanity. He wants to resign himself to the darkened moment of moonset, but he has not forgotten the days when his valiant eyes and the blade of a long sword illuminated each other. On top of his ruminations resounds a Buddhist connotation, as the title of the poem, “Quzhu” 去住 (Leave or stay), echoes the teaching of the Lengyanjing 楞嚴經 (Śūramgama-sūtra) that all worldly attachments are illusions and that only by recognizing the fluid nature of “leaving” (relinquishing) and “staying” (containing) can one dissipate their demonic spell.49

By trying to free himself from all attachments so as to assert individual integrity, the poet had to come to the harder question: whether he should also let go of literature, the form that first registered his attachment to the turmoil of his time. Since 1922 Tai had experimented with various forms to express his historical concerns, and his recent engagement with classical-style poetry represented an effort to redirect his focus beyond the immediate, national context. But judging by “Leave or Stay,” Tai presented a subjectivity whose feelings of disorientation and desire for redemption were so profound that they could no longer be contained by poetic evocations. When poetry seems to show its limitations, what other form can be adopted to express such a sense of historical disquiet?

And History Took a Calligraphic Turn

In the heyday of the Second Sino-Japanese War, Tai Jingnong took up a new form of artistic creation—calligraphy. Although he later claimed that it was no more than a pastime during the war, calligraphy marked a turning point in his career. Tai carried on with his calligraphic practice even after his relocation to Taiwan in 1946. By the early sixties, he had been recognized as a renowned calligrapher, and his early literary achievement was eclipsed.

Why did Tai Jingnong turn to calligraphy in the midst of national turmoil? Tai provided an answer in his eighties: “When the War against Japanese Aggression broke out, I went to Sichuan. There I passed my spare time by doing calligraphy.… Unfortunately it was turbulent times and I could not devote much of my time to this art. I came to Taipei after the War and I often felt depressed during my spare time after teaching and reading. So I took up the brush again to vent my feelings.”50 Calligraphy served as a distraction from harsh reality. This is a modest statement. For someone who had once made a radical break with traditionalism, to rediscover this time-honored art could not have meant he was seeking merely distraction. Like classical-style poetry, calligraphy offered a new way for Tai to engage with Chinese modernity, which appeared in crisis in the mid-twentieth century.

At stake were the politics and graphics of writing and their ability to represent modern China. One of the motivations of Chinese cultural modernization arose from literary reform, of which language re-form became a paramount goal. Classical Chinese was deemed obsolete and therefore should make way for the vernacular language, a more lively and democratic communication tool. This language renovation had two goals: to change the script system at both syntactic and semantic levels so as to facilitate a transparent inscription of the real; and to update the sound system in both articulation and acoustic impact so as to generate a dynamic interlocutionary circuit. At the material level, the renovation was reinforced by the rise of print technology and the introduction of Western-style writing instruments. Implied in this language project is a pedagogical mandate of reinscribing the Chinese mindset, a mimetic belief in the accuracy and immediacy of linguistic representation, and a truth claim based on seeking national solidarity.

Nevertheless, Chinese writers and literati already had doubts about the hegemonic power of this new writing project when it was first advocated. Lu Xun, for instance, wrote his “Kuangren riji” 狂人日記 (The diary of a madman) in 1918 to register the schizophrenic nature of the relationship between classical and modern script systems, as well as within each system, and throughout his career he never ceased to question the assumption of the total communicability of (vernacular) language and writing. Lu Xun’s skepticism could extend even to the material dimension of Chinese script technology. Did his Madman write his anticannibalistic message with a brush or a fountain pen? The question brings to mind Lu Xun’s own preference for the brush to compose his modern works, which had to do with his upbringing.51 Most of the manuscripts he left were written with the brush, which prods us to rethink the relationship between language and inscription, inscription and instrumentality.

Traditional critics have praised calligraphy as a “picture of the mind,”52 suggesting its visual capacity to reflect the imprints of the mind vis-à-vis the world. Thus, calligraphy is treated as part of the manifestation of wen 文, or “patternings,” of cosmic and human interactions.53 Such an assumption strongly emphasizes the pictographic root of Chinese writing despite the fact that in practice, it is a far more complex system.54 On the other hand, calligraphy has been equally known as an art that relies heavily on a tradition of imitation, copying, and transcribing. “To lean over” (lin 臨) by placing a model next to a sheet of paper and reproducing the characters freehand, and “to make a tracing” (mo 摹) by placing a sheet of paper over the model and tracing the characters stroke by stroke, have always been hailed as fundamental to any creative effort.55 In other words, the “aura” of calligraphy presupposes an acquired skill of approximating existing models. This is why various forms of inscriptions, from stone rubbings to “outline and fill-in” (shuanggou kuotian 雙鈎廓填), constitute a major portion of the calligraphic repertoire. As an art that turns the means of writing into its own end, calligraphy thus foregrounds the double bind in the Chinese writing system, between being a memento of a script system said to highlight ideographic—even pictographic—transparency and a reminder of the circuitous, mediatory traces of an ancient tradition of inscription.56

Despite its antitraditionalist agenda, the May Fourth call for renewing the Chinese script system carried on instead of doing away with the duplicitous premise inherent in calligraphy. Lu Xun was among those who noticed this, and he took issue with it. Besides writing about iconoclastic subjects with recourse to the brush, Lu Xun was fascinated with the dark realm of silence where voice is muted and writing becomes illegible. While he promoted modern-style writing, Lu Xun had a hobby of collecting and deciphering ancient stone rubbings.57 Given that his time witnessed the advent of mechanical reproduction, Lu Xun’s study of inscriptions on steles and other ritual and art objects may appear totally dated. But through re-membering the past as faded, unintelligible inscriptions, he demonstrates a critical reflection on the opacity and untenability of writing and meaning over time, and the complacency of the enlightenment project in facing the unknown territories of history.

Twenty years Lu Xun’s junior, Tai Jingnong belonged to the generation who first experienced the outcomes of the May Fourth Movement. His new-style writings attested to the fact that he could produce fine works in accordance with the prevalent literary discourse. But Tai came to realize that this new literature, together with its script and sound implications, was showing its limitations. Where it emancipated thought, it imposed more severe ideological strictures; where it incited “calls to arms,” it was ever ready to silence any rebellious echoes. When he took up classical-style poetry, Tai was already gesturing against the modern institution he had helped establish. But not until he turned to calligraphy did he find a medium that, thanks to its generic indeterminacy in visual and textual terms, could both contain his trauma and convey his resistance to the status quo. Lu Xun’s example of studying stone rubbings could have provided Tai Jingnong a model to emulate.58 But whereas Lu Xun was content with collecting and decoding duplicates of ancient inscriptions, Tai Jingnong went one step further to draw and create a graphic world of his own.

One more dimension of Tai Jingnong’s calligraphic work merits attention: inscription of the diaspora. The fact that Tai’s discovery of calligraphy paralleled his refugee experience in Sichuan makes one rethink the conditions of artistic creation amid national catastrophe. Although traceable to ancient times,59 calligraphy did not become a sanctioned form of art until after the massive migration of Chinese people from the north to the south in the fourth century, as a result of the invasion of nomad peoples.60 Although paper and brushes were available by the Eastern Han era, engravings on steles and vessels, along with writings on wood and bamboo panels, had dominated script technology in the north. It was in the hands of the émigré literati to the south that calligraphy evolved to become the form we know today, an art thriving on ink and moisture, paper and the brush. Calligraphic exercises proliferated at this time, and masters such as Wang Xizhi 王羲之 (303–361), the “Saint of Chinese Calligraphy,” arose to set the standard for centuries to come. In contrast to the northern tradition, which appears stately in style and is mostly anonymous in authorship, the southern tradition brings out individual agility and lyricism later regarded as the essence of the art. This is the contrast between the northern, “stele” tradition and the southern, “script” tradition.

The script tradition, nevertheless, is highly vulnerable thanks to both the easily perishable condition of writing materials and the importune circumstances of writing. No single original piece of Wang Xizhi’s calligraphic work has survived; the Wang canon derives its power from rubbings, copies, and imitations. But the “existential” nature of calligraphy may drive home its unique charm: that it is an art whose originality is subserved by its duplicity, and that its aesthetic intelligibility surfaces only as the content of writing gradually gives way to (or gives rise to) the form of writing over time.

Tai Jingnong’s iconoclasm had all along been underlain by a subtle recognition of the traces of historicity. He was involved in two preservation campaigns in his younger days: the project of collecting folksongs in his home province, Anhui, in 1924, and the Society of Preservation of Beijing Cultural Artifacts in 1928, in the aftermath of the warlord regime’s withdrawal from the ancient city.61 The Japanese invasion brought Tai a more poignant awareness of Chinese culture in crisis; when he picked up his brush, he could not have sought a pastime, as he claimed, any more than he set out to inscribe, to give shape and meaning to, the ruins of the present literally in light of the legible strokes and lines—“traces”—left by history.

In the midst of massive cultural vandalism and human atrocities, Tai wrote as if running a personal rescue mission to salvage the last resort of Chinese culture, its script system, from demolition. But in view of the frail material condition of calligraphy and its inherent aesthetics of duplicity, this seems perhaps a quixotic quest, especially considering his move to Taiwan after 1946. While he became more and more famous as a calligrapher, a preserver of that essential form of the Chinese script system, Tai Jingnong at the same time had to face the bitter fact that his homecoming dream grew ever dimmer. Did the representation of Chinese characters serve for him as the crystallized form of cultural essence or residual traces after the dissipation of history?

Tai Jingnong started his training in calligraphy in childhood, under the tutelage of his father. His first models were the Huashan Inscriptions (Huashan bei 華山碑, 165) and Deng Shiru 鄧石如 (1743–1805) for lishu 隸書 (official script), and Yan Zhenqing 顔真卿 (709–785) for kaishu 楷書 (regular script) and xingshu 行書 (running script). This curriculum is important in that it represents the twofold tradition of Chinese calligraphy. The Huangshan Inscriptions mark one of the greatest achievements of the “stele form” of official script for their stately and grave strokes, and Deng Shiru’s calligraphy is known for reviving this stele form in the mid-Qing dynasty. Yan Zhenqing has always been celebrated as the person who redefined the “script form” up to the mid-Tang dynasty by turning it from the slim, sloped, and sumptuous trend into upright, muscular, and more controlled strokes. That Yan was able to blend regular script techniques drawn from zhuanshu 篆書 (seal script) and official script, thus lending his brushwork a gravity suggestive of stone inscriptions, would later become an important inspiration for Tai Jingnong.

Tai did not pursue calligraphy during the post-May Fourth days, considering it “petty pleasure,” but he did not give it up either, since writing with the brush was still customary for his generation. His style at this time shows Lu Xun’s influences, relaxed in brush lines while mindful in composition.

When resuming his calligraphic work in Sichuan, Tai Jingnong first made Wang Duo 王鐸 (1593–1652) his model. A pioneer in late Ming calligraphy rejuvenation, Wang is known for his versatility and innovative, robust interpretation of the established paradigm. Tai’s teacher at Peking University, Shen Yinmo 沈尹默 (1883–1971), a renowned calligrapher in his own right, however, denigrated Wang’s style as “too ripe and [lacking in] subtlety” (Lanshu shangya 爛熟傷雅),62 and therefore urged Tai to look for a different model. Shen Yinmo’s critique may not be fair, as Wang Duo has been commonly acclaimed for rendering a raw, “dynamic force,” quite opposite to Shen’s opinion.63 The real reason for the negative critique, as scholars have pointed out, may lie in the fact that after the fall of the Ming, Wang Duo surrendered to the Qing.64 In other words, Wang’s calligraphy appears suspect because he was a disloyal subject. The characters of calligraphy were taken as an emblem of the character of the calligrapher. Shen Yinmo was not alone in recapitulating the old “phrenology” of calligraphy. It just so happened that Tai Jingnong’s new friend Chen Duxiu had criticized Shen Yinmo’s own calligraphy for “being superficial to the bone” as well as “showing no character beyond his characters.”65

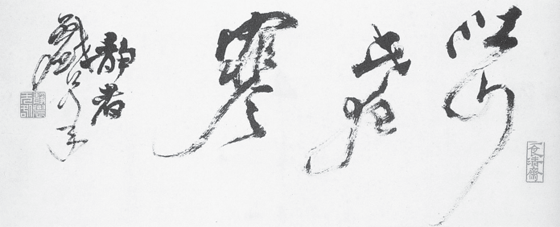

Lu Xun’s calligraphy for Tai Jingnong (1932). Courtesy of Mr. Tai Yi-kung

Tai Jingnong’s calligraphy (early 1930s). Courtesy of Mr. Tai Yi-kung

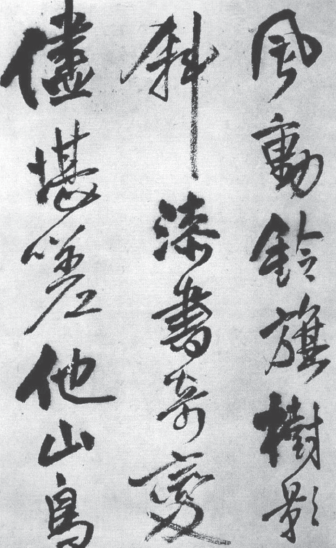

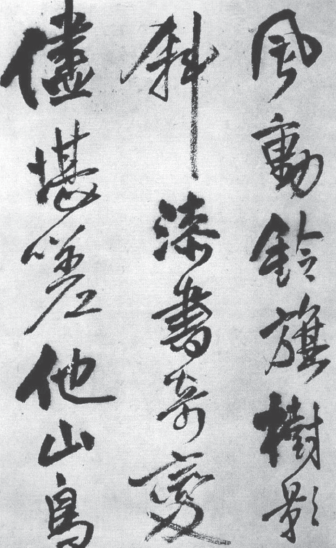

It was at this time that Tai Jingnong discovered the calligraphy of Ni Yuanlu 倪元璐 (1593–1644).66 Ni Yuanlu was Wang Duo’s colleague in Emperor Chongzhen’s 崇禎 court; like Wang, he was an experimentalist in reviving late Ming calligraphy. Ni and Wang, together with other fellow calligraphers such as Huang Daozhou 黃道周 (1585–1646), were all responding to the advocacy of Dong Qichang 董其昌 (1555–1636), the leading calligrapher of their time, that calligraphy should call forth the effect of the raw and the strange rather than complying with familiar patterns.67 While Wang Duo’s style appears to be daring and exuberant, Ni’s is distinguished by a tighter character structure and more careful modulation of muscular force. His running script shows a special angular feature at the beginning and bending strokes, as if he were wielding the brush to break away from the normal, poised rule of configuration, only to hold back his strength at the moment of its release. Because of the lengthened pause, there appears a chromatic contrast between the strokes saturated with ink and those short of it. The result is a dramatic tension that is expressive and forceful on one hand and pensive and subdued on the other.

Both Ni Yuanlu and Wang Duo belonged to the Donglin 東林 faction in political affiliation, which regained its power during the Chongzhen reign; their political influence certainly helped increase their prominence in the calligraphic art. But there is one difference between the two: Wang Duo survived the fall of the Ming and eventually chose to serve the Qing, but Ni Yuanlu hanged himself when Li Zicheng 李自成 took over Beijing. Before his death, Ni is said to have picked up a brush and written slowly on his desk: “The capital in the south still has a chance. Death is my obligation; do not coffin my body so that my pain can be inscribed.”68

Tai Jingnong first had access to Ni Yuanlu’s calligraphy in the summer of 1942,69 coinciding with his completion of The Saga of the Fall of the Ming. It is not difficult to imagine how, having spent months on a dark exposé of dynastic cataclysm, Tai would have appreciated Ni’s story of integrity and martyrdom, and more, how he found in Ni’s calligraphy a graphic testimony to the linkage between Ni’s political life and his artistic representation. One can point out that such a view reflects biographical and intentional fallacy. Just as Wang Duo’s calligraphy need not appear “disloyal” because of his surrender to the Qing, so Ni Yuanlu’s may display something other than a mere reflection of his political integrity. Nevertheless, the interplay between a calligrapher’s style and his character can be real. Insofar as it is an art whose creativity presupposes expertise in copying and transcription, calligraphy demands inquiry into its multiple layers of intention and mediation: a representation of characters that in their own turn are representations of actual and imaginary referents. Once its representational sequence is set in motion, calligraphy generates the circulatory power of “iconology.”70 This shows that the cross-reference between script and personality may be less arbitrary than overdetermined, and that any exegesis of character requires a continued shuffling of semantic and semiotic signs.

Wang Duo’s calligraphy. National Taiwan University Press

Ni Yuanlu’s calligraphy. National Taiwan University Press

I argue that by calling on Ni Yuanlu’s life and works, Tai Jingnong acted out the imaginary of loyalism (yimin yishi 遺民意識) and the discourse of “southern migration” (nandu 南渡), two major historical topics during the 1940s. Whereas loyalism refers to a former subject’s mourning the loss of cultural and political orthodoxy and desire to restore it,71 “southern migration” refers to the Chinese people’s southbound exodus as a result of political upheaval and their effort to rehabilitate their civilization. If loyalism highlights a willed anachronism in response to a rupture of history, “southern migration” points to the pathos and travail arising from displacement and exile. On the scene of writing, both are registered by a poetics of belatedness, trauma, and longing to return to the site of origin.

These two notions were made known during the war thanks to such prominent intellectuals as Chen Yinke 陳寅恪 (1890–1969) and Feng Youlan 馮友蘭 (1895–1990). Chen Yingke has lamented the exodus as follows:

Migration to the south made me mourn things past,

Return to the north may well be a wish in my reincarnation.72

南渡幾回傷往事,

北歸衹留待來生。

By contrast, Feng situated the exodus in a more optimistic perspective, calling it the “fourth southern migration” in Chinese history. The previous three southern migrations, according to Feng, happened in the Eastern Jin of the fourth century, the Southern Song of the thirteenth century, and the Southern Ming of the seventeenth century. All four migrations were caused by foreign invasions of the nomadic peoples, the Nüzhen Tartars, the Manchus, and the Japanese, and all brought Chinese civilization to a crucial point where political legitimacy, cultural and intellectual coherence, and affective authenticity threatened to collapse.73 Feng proclaimed that the fourth southern migration would end with a return to the north and a restoration of political orthodoxy.

In this light, Tai Jingnong’s historical fable The Saga of the Fall of the Ming and his calligraphic emulation of Ni Yuanlu become significant, because they represent the dialectic under the discourse of loyalism and “southern migration.” Whereas The Saga sneers at any hope of cultural and political renaissance, the calligraphy in the style of Ni Yuanlu confirms the lasting value of loyalism. Still, Tai Jingnong’s own calligraphy offers the most compelling example of the interaction of loyalism and “southern migration.”

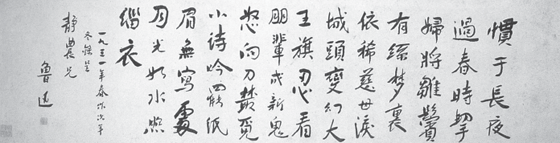

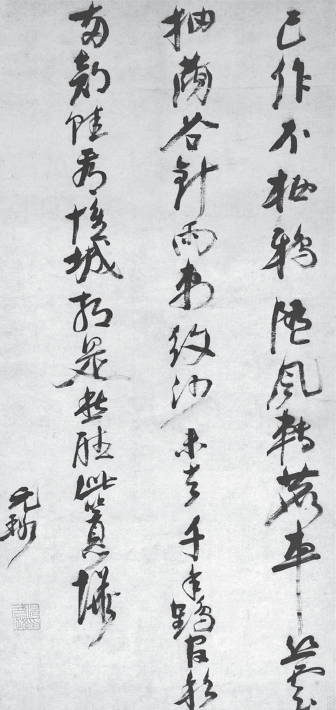

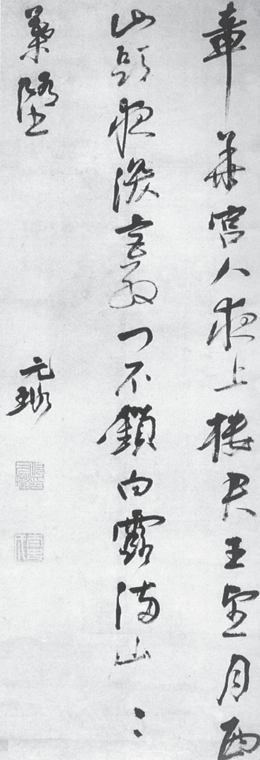

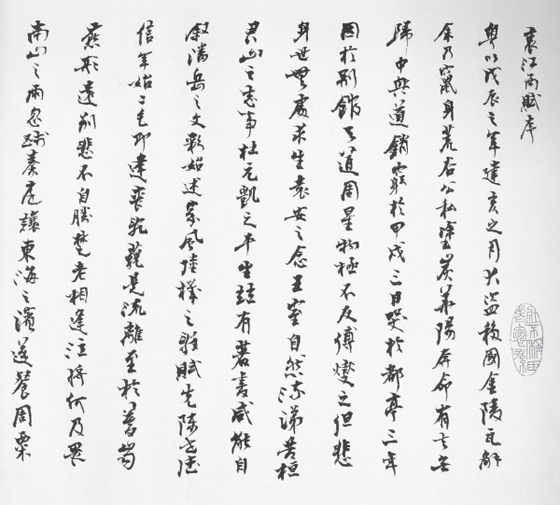

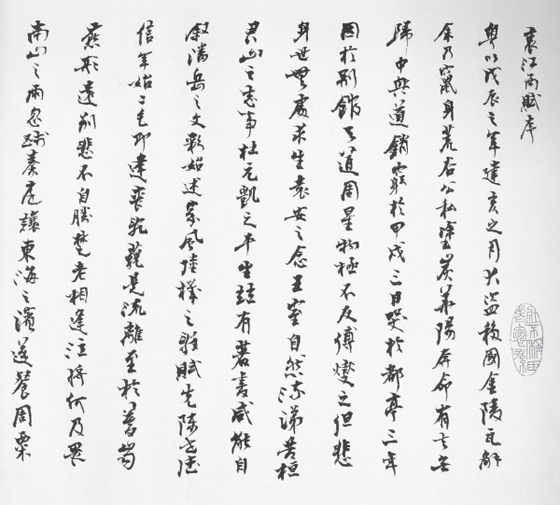

Take for example the scroll that has both Tai Jingnong’s transcription of Lu Xun’s poetry in 1937 and his postscript written in 1946. Tai transcribed all of Lu Xun’s classical-style poems on the eve of fleeing Beijing in 1937, a symbolic gesture to bid farewell to his mentor, who had passed away a year before, and to the city he would never have a chance to revisit. Executed in running script, Tai’s style appears uncongested in character structure and slender in strokes, reminiscent of Lu Xun’s style. The postscript, written nine years later, shows a marked difference. The chromatic scheme is darker and richer in the contrast of moisture and dryness; all characters display a leftward-slanting orientation, and the brushstrokes appear longer in vertical descent and resolute in laying strength—patent traits of Ni Yuanlu’s style. While the formations of characters show pointed features, with the pie 撇 and na 捺 strokes ending with small upturned hooks, the overall style shifts along with the text from regular script to running script, hinting at the calligrapher’s increasingly agitated mood.

This graphic transformation becomes more suggestive if one refers to the text and context of the writings. The transcription of Lu Xun’s poetry was done in Beijing, and it was dated August 7, 1937, which, as Tai noted in the 1946 postscript, marked the eve of Japanese troops’ occupation of the city. Three days after the fall of Beijing, Tai fled and began his exile. Looking back, he was saddened by the hardship he had been through and all the more troubled by the aftermath of the war. He wrote, “The civil war has broken out all over China. Refugees [from the previous war] still could hardly find their way home; their predicaments are worse than ever before. How could the situation have become like this?”74

A supplement to the 1937 transcription of Lu Xun’s poetry, the 1946 postscript lays bare the bitter irony that victory had taken history to a downturn, and that the fall of Beijing nine years before might well have foreshadowed a dark future yet to come. Through his changed calligraphic style, Tai brought Lu Xun into dialogue with Ni Yuanlu. If the image of Lu Xun’s poetry and calligraphy permeates Tai’s 1937 script, it is overwritten, so to speak, by that of Ni Yuanlu in the 1946 postscript, in both historical and pictorial terms. Ni Yuanlu’s style, angular in composition and sinewy in brush force, enabled Tai Jingnong to dramatize his own anguish about the worsening national fate; it also contributed an additional dimension to the melancholia of Lu Xun’s poetry regarding the political disarray of Republican China in an earlier period.

Ni Yuanlu’s calligraphy. National Taiwan University Press

Tai Jingong’s calligraphy in the Ni Yuanlu style. Courtesy of Mr. Tai Yi-kung

Tai Jingnong’s calligraphy of Lu Xun’s classical-style poetry (1937). Courtesy of Mr. Tai Yi-kung

Tai Jingnong’s calligraphy (1946), postscript to his calligraphy of Lu Xun’s classical-style poetry (1937). Courtesy of Mr. Tai Yi-kung

Moreover, underneath Tai’s imitation of Ni Yuanlu looms the latter’s suicide in defending Beijing, a martyrdom paralleled by Tai Jingnong’s surviving the fall of Beijing in another cycle of historical atrocity. Whereas Ni Yuanlu committed suicide to consummate his loyalty, Tai Jingnong survived to lead a life ever shadowed by the mourning of a loyalist. If the 1937 transcription is already a postscript—an elegiac textual and imagistic reenactment—to Lu Xun’s calligraphy, the 1946 postscript can be read as a postscript to a postscript, a belated reinscription of Lu Xun’s style via Ni Yuanlu’s. Such an elegiac thrust haunts Tai Jingnong’s calligraphy, and it drives home the aesthetics and politics of mortality embedded in his loyalism.

TAI JINGNONG MOVED TO TAIWAN in the fall of 1946 to take a professorial appointment at National Taiwan University; he was planning to stay only for a short period, so named his residence in Taipei “Hut for resting feet” (Xiejiaoan 歇腳盫). This was, however, a time when one could hardly find a place to rest. On February 18, 1947, Xu Shoushang 許壽裳 (1883–1948), Chairman of the Chinese Department of National Taiwan University and close friend of Tai Jingnong as well as Lu Xun, was found killed at his home, a murder mystery never solved.75 Xu’s successor, Qiao Dazhuang 喬大壯 (1892–1948), after a short period of service, returned to Shanghai and drowned himself that summer.76 By then, the civil war had engulfed China and made travel extremely hazardous. When the Nationalist government retreated to Taiwan in the summer of 1949 and declared martial law later, Tai found himself stranded together with a regime he had least supported during his years on the mainland.

Tai Jingnong was asked to chair the Chinese Department of National Taiwan University after the suicide of Qiao Dazhuang; thus began his legendary tenure of the next two decades.77 Although determined to concentrate on teaching, he could hardly have been undisturbed by the severe political circumstances, particularly the antileftist crackdown during the fifties. It was at this time that he again turned to calligraphy. While Ni Yuanlu remained his major model, Tai started to explore other styles, and he paid special attention to the official and seal scripts as demonstrated in ancient stele engravings. One major model was the inscriptions of “Shimen song” 石門頌 (Ode of stone gate) in official script style,78 known for vigorous but graceful, flat strokes and unassuming structures. If Ni Yuanlu’s style helped Tai Jingnong channel out a tense and melancholy disposition, the “Ode of Stone Gate” inscriptions showed him a new option of archaic poise and spontaneity.

“Ode of Stone Gate.” National Taiwan University Press

One of the earliest essays Tai Jingnong published in Taiwan is “Lun xiejingsheng” 論寫經生 (On sutra transcribers, 1950), a study of the transcribers of Buddhist texts in medieval China.79 They were preservers and transmitters of precious knowledge, as Tai observes, but they had an obscure social status and remained mostly anonymous. The essay invites an allegorical reading. Tai Jingnong seems to imply that his engagement in calligraphy is not unlike the work of those medieval transcribers, who copied rare texts day and night to the exclusion of their own identities and intents. Tai cultivated a self-erasing posture that, instead of being a writer, he was merely a copier of classical characters.80

On a closer look, nevertheless, one discerns in this posture a more profound intention. Tai’s calligraphy may “lay bare” the graphic constructs of the Chinese characters in the formalist sense, only to encrypt them by investing in the lines and curves, chromatic schemes and character structures a rich taxonomy of meanings. I argue that through his calligraphic inscription in varied styles, Tai Jingnong enacted a palimpsest politics, or an “encryptography,”81 concealing and revealing alternately the layered meanings—and feelings—of writing and transcription in the art of calligraphy.

At the core is Tai Jingnong’s diasporic condition in Taiwan, a condition that proved to be far more complex than implied by the discourse of loyalism or “southern migration” in which he engaged during the war. Located south of the traditional endpoint of southern migrations, Taiwan in the late forties was linguistically and culturally still under Japanese influence while politically subject to Nationalist hegemony. It was a “waste land” to many recent mainland émigrés. Had he not taken the teaching position in 1946 by chance, it is highly doubtful that Tai would have followed the exiled Nationalist regime, unworthy of his loyalty from the outset, to the island. If “southern migration” already implied a politics of dispersal and a poetics of loss, Tai Jingnong had to recognize the doubly poignant implications. Resonant here are Ni Yuanlu’s words before suicide: “The capital in the south still has a chance.” Could the Nationalist retreat to Taiwan be taken to mean the “fifth southern migration” in Chinese history, although the Communist regime had declared its legitimacy by reclaiming not only the north but the whole mainland? Factors of cultural and political destitution aside, as a “northerner,” Tai felt most unaccustomed to the tropical climate of the island, sometimes “so depressed and restless as to lose self-control.”82

Under these circumstances, calligraphy became a testimony to Tai Jingnong’s “tristes tropiques,” in three senses: as an aesthetic token of his nostalgia for the cultural legacy of the north and the mainland; a political alibi that kept his wavering loyalism in an ambiguous form; and a therapeutic measure used to cope with his melancholy of southern migration. But these interpretations still do not spell out the thrust of his calligraphic turn. I suggest that at his most provocative, Tai Jingnong came to realize that calligraphy did not merely “represent” his predicament; rather, his predicament helped disclose something always already inherent in calligraphy, as an art of transmigration and dissemination of topos and logos.

Of all pictorial forms of Chinese art, calligraphy has been noted for its rhythmic movement in terms of both the exercise of brushwork and the consequent formation of characters on paper. To that effect, calligraphy is frequently likened to music and dance, as an art that acquires a skill of rhythmic procession and chorographical orchestration.83 Critics have stressed that calligraphy unfolds itself along with the motion of the brush strokes, in coordination with the movement of the calligrapher’s body and mind, to the point where a harmonious display of ink work is accomplished.84 What they tend to overlook is the fact that, besides being an art of “becoming” and performing, calligraphy, like music and dance, is also an art about dissonance in time and dissolution in corporality. That is, during a finite span of time, a calligrapher engages in a compressed infinity where ink moisture dissolves into paper freely, brush tips slide into multiple configurations—almost a Dionysian flight out of the formalities of writing.85 On the dark side of his resolute force and lively rhythm there lies a continued struggle between contingency and its containment, becoming and its loss when that finite time of composition is over. In the end, calligraphy stands as a demonstration that time is also about decomposition, and writing discloses its ephemerality.

Given his elegiac modeling of Lu Xun’s and Ni Yuanlu’s style, Tai Jingnong knew better than most of his contemporaries that real calligraphy is as much about emancipation and life force as about pain and mortality. It throws the artist into the full instant at once, more completely and profoundly than the characters being drawn can ever communicate. It places the graphics and semantics of writing at the site where contradictions and repetitions, losses and redemptions of life are often plastered over by the truth claim of history. Exiled on an island south of the traditional boundary of “southern migration,” Tai Jingnong was made to learn his calligraphic lesson the hard way. More than giving forms to the characters conceived to be written down, the lines and dots of calligraphy pointed him to passages into the terra incognita of history, the heart of darkness.

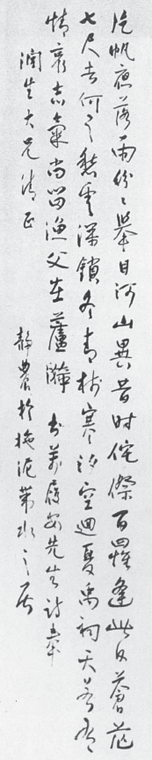

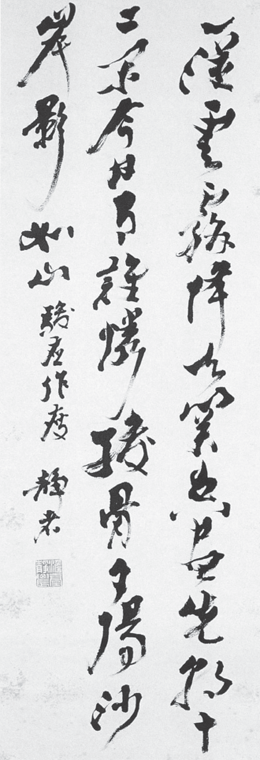

Take a look at his scroll “Jiangshan ciye han “江山此夜寒” (Mountains and rivers chill at this night). The phrase is derived from the poem by the Tang poet Wang Bo 王勃 (650–676); the last two lines read:

Loneliness looms over the pavilion of farewell

Rivers and mountains chill at this night.86

Tai Jingnong, “Rivers and Mountains Chill at This Night.” Courtesy of Mr. Tai Yi-kung

寂寞離亭掩,

江山此夜寒。

The poet describes his lonely feeling at bidding farewell to his friend, in correspondence to the desolate and chilly atmosphere amid the natural scenery. Insofar as jiangshan (rivers and mountains) refers to the conventional trope of the national landscape, we can discern Tai Jingnong’s intention to project his personal feeling of loss onto the historical canvas. His calligraphic configuration renders something more. Of the five characters, jiang (river) and shan (mountain) are set to parallel ci (this) and ye (night), thus calling forth the subtle dialogic between the seeming eternity of nature/nationhood and the momentary existentiality of one single night. Both jiangshan and ciye, however, are made to succumb to the character han (cold, chill), which appears vertically prolonged in a line of its own and outsized in proportion to both jiang/shan and ci/ye. At the visual level, both “the national landscape” and “this night” are “seen” as overpowered by the enshrouding “cold.”

Nevertheless, as if trying to rescue the characters from their grave implications, Tai Jingnong writes them in the cursory script, which unleashes a surprising momentum from their semantic and graphic boundaries. The calligrapher’s desolate feeling is thus “compensated” for by his lively strokes. Such a pictorial drama reaches its climax in the inscription jingzhe xibi 靜者戲筆 (Master quietude’s playful strokes). Whereas jingzhe (with jing referring to Tai Jingnong) is rendered in a reserved manner, suggesting the calligrapher’s self-esteem of quietude, xibi brings out his playful desire in full eruption.

This leads back to the two most conspicuous models that Tai Jingnong tried to yoke together during his Taiwan years: the “script” model represented by Ni Yuanlu and the “stele” model represented by the “Ode of Stone Gate” inscriptions. Ni Yuanlu was a southerner, and his style, forceful and recalcitrant as it appears, reflects the “script” tradition in both aesthetic and material terms. By contrast, the “stele” model is derived from the north, found mostly on the stone engravings of the Han and pre-Han periods. By turning from Ni Yuanlu to the “Ode of Stone Gate” inscriptions, Tai introduced to his “script”-oriented calligraphy a sense of solemnity and weight characteristic of the “stele” model. Beyond this shift of aesthetic taste, perhaps Tai also intended a political statement. Both chronologically and geographically, the “stele” tradition of the north preceded the “script” tradition of the south. To hark back to the “stele” tradition, therefore, indicates a search for an archaic, and therefore presumably more authentic, form of writing—a reversal of the discourse of “southern migration.”

More significantly, the mixture of Ni Yuanlu’s style and the “Ode of Stone Gate” inscriptions informs Tai Jingnong’s sober meditation on temporality and the work of mourning. Ni Yuanlu is at his best in the running script style, which shows an urgency of mood and a swift modulation of brush strokes and moisture. It implies a temporal effect of both progressiveness and changeability. The “Ode of Stone Gate” inscriptions, in contrast, appear to be stonework resurrected from centuries of oblivion, reminders of a bygone age no longer representable except for fragments of engravings. Ni Yuanlu prods one to conceive of a calligraphic aesthetics brought to consummation by political calamity and personal annihilation; his martyrdom becomes a crucial subtext of his script. By contrast, the “Ode of Stone Gate” inscriptions, scribe and engraver unknown and characters barely legible after thousands of years of damage and erosion, teach us a different lesson about the attrition of time and the inevitable fading away of any historical establishment.

We can now return to the scroll “Life is hard indeed; the way has many branches” cited at the beginning of this chapter. As has been discussed, this was Tai Jingnong’s most favorite saying in his later years, and it gives rise to multiple interpretations. “Life is hard indeed” is underlain by the skepticism that even death can hardly bring any resolution; “the way has many branches” leads to the realization that one may lose one’s life in pursuit of “the Way,” which proliferates into infinite directions. Reviewing his own life full of tortuous adventures from the north to the south, as revolutionary, fiction writer, new- and old-style poet, scholar, educator, artist, leftist, loyalist, and “postloyalist,”87 Tai Jingnong had every reason to savor the paths he had taken and those he had not. Coming to mind again is Ruan Ji’s riding an oxcart on endlessly forked paths and his forced return in tears whenever his cart reached a dead end. By reinstating the old tale in recourse to brushwork, Tai Jingnong in his last years was ruminating more vigorously than ever before on the way of his life, its multiplying branches, dead ends, and ways out. A Sisyphean gesture indeed. But insofar as with his brush he is testing repetitively the boundaries of death, Tai can also be seen as playing a subtle Freudian game of fort-da.

Examining not only what Tai wrote but also how he wrote it, one realizes the role calligraphy plays in mutely articulating his diasporic consciousness. The scroll, written in running script, bears clear features derived from Ni Yuanlu’s model: all character structures slant up toward the right, and the “flat hook” (pinggou 平鈎) of the character shi 實 (indeed) and the sweeping right strokes (na 捺) of the characters ren 人 (human), dao 道 (the way), duo 多 (many), and qi 歧 (branches) are written in a strong, sinewy manner, such that they end with upward inclinations, as if the calligrapher would not let go of the otherwise downward turn of the strokes. The characters da 大 and duo 多 appear ink-saturated, coincidentally rendering a visual counterpart to the implication of excess of both characters, while the right long stroke of ren 人 and the leftward (pie 撇) stroke of shi 實 show uncommon curvatures as a result of added brush force, thus reflecting the calligrapher’s enforcement of his understanding that “human” life is “indeed” hard.

Moreover, Tai Jingnong’s graphic illustration of the hardship of life and the multiplying branches of the Way is enriched by his consultation with the “stele” model as encapsulated by the “Ode of Stone Gate” inscriptions. The way Tai Jingnong handles his brush brings about a chiseled effect associated more with engraving than merely writing. Also, the composition of the characters is more square than that of typical Ni style; in particular, the center parts of nan 難, duo 多, and qi 歧 are given more space and therefore create an unexpected sense of relief.

Critics have pointed out that at its mature stage, Tai Jingnong’s calligraphy appears heavy and dignified at first look, but it betrays ethereal and even feminine touches wherever square strokes give way to sudden willowy twists and resolute outbursts of force come to reserved endings.88 The scroll under discussion serves as a good example. Throughout his brushwork the calligrapher seems to play with a delicate balance between the Ni Yuanlu and the “Ode of Stone Gate” models, between improvisational swiftness and premeditated gravity. He seeks for his “quirk” of eccentricity and melancholy an anchoring force of historicity, yet is wary that the deadly monumentality of any form may stump his bent for recalcitrance and individualism. Shuttling between the two styles, Tai acts out the phantasmagoric themes of his early literary works. As with “The Comet of a Death House,” he looks for a kinetic thrust to break away from a restricted place of incarceration; as with the “Phantoms of the Spring Night,” he could not inscribe anything without conjuring up the ghost from the world of ruins.

Coda

In October 1988, two years before he passed away, Tai Jingnong published a collection of personal essays titled Longpo zawen 龍坡雜文 (Miscellaneous essays of dragon slope), which reminisces about his old acquaintances, literary and artistic explorations, and personal experiences from the 1930s to date. The collection won immediate attention, for it reveals a life full of ups and downs while rendering an understated, almost casual, style—lyricism at its most subtle. The most compelling essay is “Shijing sangluan” 始經喪亂 (A first encounter with losses and disturbances, 1987), in which Tai looks back at his adventure in the summer of 1937, when the Marco Polo Bridge Incident broke out. Tai happened to be in Beijing at the time and was anxious to be reunited with his family in Anhui. However, his friend Wei Jiangong 魏建功 (1901–1980) asked him to deliver a message to Hu Shi, then in Nanjing, regarding the future of Peking University, which was already under Japanese occupation. After a harsh, tortuous trip, Tai finally arrived in Nanjing, as the Nationalist government was vacating in the midst of severe bombing. Tai recalls how bombs dropped right into his friend’s house while he was visiting, and how Nanjing was enshrouded by fear of the impending fall. But Tai’s recollection smacks of an unlikely ironic mood, as historical hindsight has taught him: “this was merely my first encounter with losses and disturbances.”89

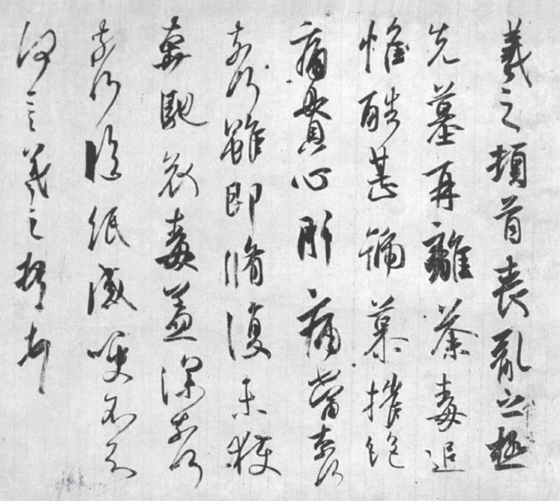

With the phrase sangluan, losses and disturbances, Tai Jingnong was echoing Du Fu, who describes his predicament in exile as a result of the riot of An Lushan: “I have been unable to fall asleep since undergoing losses and disturbances; so deeply immersed in tears over the long night” (自經喪亂少睡眠,長夜沾濕何由徹).90 Tai Jingnong also could have been thinking of Xie Lingyun 謝靈運 (385–433), who deplores that “The Middle Land used to be in losses and disturbances, but have the losses and disturbances come to an end yet?” (中原昔喪亂,喪亂豈解已).91 Even more likely is Tai’s identification with Yu Xin 庾信 (513–581), who in “Ai Jiangnan fu xu” 哀江南賦序 (Preface to the rhapsody of lament for the south) states that “losses and disturbances befall [him] at the beginning of middle age, and continue all the way to old age” (信年始二毛,即逢喪亂,藐是流離,至於暮齒).92 One of the most talented courtier poets of the Liang (one of the Southern Dynasties in medieval China), Yu Xin was sent to Western Wei (one of the northern countries established by the nomad peoples) as cultural envoy in 554, only to be detained there until his death. During the last twenty-seven years of his life, Yu Xin witnessed from afar the downfall of his own country as a result of insurgencies, barbarian attacks, internecine fights, and usurpations, while finding himself caught in no less volatile dynastic cycles in the north, from Western Wei to Northern Qi and Northern Zhou. Despite his prestigious life in the northern courts, Yu Xin was beset in his twilight years by an increased nostalgia for his homeland south of the Yangze River, and “Rhapsody of Lament for the South” conveys his most intense feeling of loss and mourning.

Tai Jingnong, calligraphy of “Rhapsody of Lament for the South.” Mr. Tai Yi-kung

There is an ironic subtext in Yu Xin’s southward posture of longing, however. Yu’s family was originally a prominent house in the north, which undertook the “first southern migration” as a result of the fall of the Western Jin (265–317) to the barbarians decades before. Yu Xin’s nostalgia for jiangnan, the land south of the Yangtze River, betrays a deeper level of the frailties of human attachments and memories: that as time passes, even one’s sense of native soil undergoes a reorientation as a result of migration and resettlement.