THE PRECEDING CHAPTERS have examined the dynamics of lyrical manifestations in mid-twentieth-century China, highlighting a group of intellectuals, literati, and artists who each took an extraordinary path in engaging a time dominated by wars, revolutions, and diasporic adventures. Amid the national call to arms and solidarity, they sought options for selfhood and aesthetic articulation and projected personal visions in spite of—or because of—their varied political convictions. At their most provocative, they injected into mid-century Chinese and world cultural politics a poetic thrust, which I have described as the lyrical in epic time.

Case studies ranging from Shen Congwen’s literary and archaeological endeavor to Feng Zhi’s and He Qifang’s poetry, Hu Lancheng’s prose, Lin Fengmian’s painting, Jiang Wenye’s music, Mei Lanfang’s theater, Fei Mu’s films, Tai Jingnong’s calligraphy, and Chen Shih-hsiang’s criticism, exemplify not only the vigor and variety of Chinese lyricism at an unlikely historical juncture but also the precarious consequences it brought about. I take issue with the conventional wisdom that associates lyricism merely with sentimentalized subjectivity and rhapsodic artifice, arguing instead that such lyrical provocation can serve as a critical index to the structure of feeling of modern China.

In addition to Western resources ranging from romantic to revolutionary poetics, these Chinese literati and artists benefited profoundly from their own legacy of shuqing, a fact hitherto overlooked by critics. The etymology of qing suggests both sensory influx and conceptual rumination, both historical circumstance and behavioral protocol. By corollary, shuqing points to a literary or artistic genre, a mood, a representational system, or even an ideology that is as much emotionally motivated as historically occasioned. The intertwined connotations of qing and shuqing enabled these writers, intellectuals, and artists to spell out complex personal responses to national upheaval. Some of the theoretical ramifications arising therefrom, such as xing and yuan, feeling/sentience and materiality, politics and histrionics, prove to be stunningly relevant even to our time.

This lyrical discourse has led me to rethink the extant paradigm of Chinese modernity. I examine the double modes of the paradigm, enlightenment and revolution, arguing that enlightenment may be propelled by a utopian vision or its disavowal, and that revolution cannot move the masses without a cause that is both inspiring and spellbinding. Moreover, the discourse offers a unique form of illumination, throwing light on the entanglement of the Chinese heart in labyrinthine choices such as solipsism versus solidarity, sincerity versus authenticity, redemption versus betrayal, and silence versus sacrifice. As a result, it challenged its own raison d’être in such a time.

Finally, I argue that the lyrical in epic time constitutes an important part of the lyrical soundings in world circulation at the time, a phenomenon including critics such as Martin Heidegger, Walter Benjamin, Theodor Adorno, Cleanth Brooks, Jaroslav Průšek, and Paul de Man. While they all call on lyricism as a way to understand history and configure the world anew, these critics’ approaches are so diverse as to foreground the contentious nature of their pursuits. The Chinese cases, as has been argued throughout the book, contribute an East Asian dimension to the dialogic, furthering our understanding of its aesthetic, ethical, and political implications.

These case studies lead to the question: If lyrical provocation once served artists and intellectuals contending with mid-twentieth-century China in crisis, could it be recapitulated to bear on the circumstances of our time? Since the late 1990s there have been waves of debates about the aftermath of China’s new Great Leap Forward in a postsocialist fashion. Intellectuals from different camps have offered various diagnoses and remedies regarding the future of new China. Whereas neoleftists deplore the “depoliticization of politics” and call for another round of revolution,1 neoliberals address the necessity of civil society and call for a new campaign for enlightenment.2 Granting the new inputs they have brought into the debates, these intellectuals appear to engage with the same paradigm of revolution and enlightenment that was initiated at the turn of the twentieth century. While their arguments may bespeak the unfinished project of China’s search for modernity, they show limited ability to open up new theoretical horizons. For one thing, they are still aspiring to a solution—or a mere discourse—in grand, epic terms. At a time when revolution is struggling with its inherent spell of involution3 and enlightenment demands more critical reflection than ever on the terms of enchantment versus disenchantment, is the epic mode of thinking not itself a residual syndrome of, rather than a remedy for, the Chinese crisis of the past century? And more polemically, will the call for the lyrical/shuqing have a new chance to prove its efficacy?

The Kantian “Double Bind” and Its Chinese Alternatives

In her recent book An Aesthetic Education in the Era of Globalization (2012), Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak reflects on the status of the humanities and arts in the face of the challenges of globalization, and calls attention to the urgency of revitalizing aesthetic education. For Spivak, aesthetic education remains the strongest resource available for the cause of judgment, empathy, and sociability, because it trains one to “imagine” rigorously the multifaceted aspects of human conditions.4 She derives her proposal, particularly the part on pedagogy and public culture, from “the German Romantic and idealist conception of art as an instrument for the moral enlightenment of a mass public in a post-revolutionary age.”5 She takes her inspiration first from what she terms the Kantian “double bind,” through which Kant differentiates philosophizing reason with “intended mistake” from philosophizing reason through transcendental deduction.6 She then moves to Schiller, who allegedly takes up the Kantian aesthetic premise in an effort to reconcile the pulls of ethics and aesthetics. Schiller finds in the arts the drive of “play” through which a human being attains the synthesis of “the sensuous” and “logical or moral” conditions: “As soon as two opposing fundamental drives are active within him, both lose their compulsion and, in the opposition of two necessities, give rise to Freedom.”7

Spivak’s critique of Kant and Schiller brings her to reflect on contemporary global life, in which inequality still prevails while leftist reactions have been dwindling. She faults Schiller’s idealist reading of the Kantian double bind, which she believes “turn[s] the desire in philosophy into its fulfillment.”8 Spivak offers a rereading by way of Wordsworth, Marx, Gramsci, Derrida, de Man, and particularly the social scientist Gregory Bateson (1904–1980), from whom she draws the term “double bind” at the outset. Bateson spells out the training of human imagination in terms of “indefinite series of mutual reflections … from passing on from solution to solution, always selecting another solution which is preferable to that which precedes it.”9 Thus, taking her cue from Bateson and other critics, Spivak describes her aesthetic education as an “imagination play,” an imaginary action that results in no Schillerian closure but an incessant double bind in engaging the “abstract” and the “concrete,” “the universality of the singular,” and “democracy.”10 She concludes that “the displacement of belief onto the terrain of the imagination can be a description of reading in its most robust sense.”11

Spivak’s endeavor to reclaim aesthetic education in the new century may raise many eyebrows, for she otherwise has been known to be a deconstructionist, a Marxian postcolonialist, and a gender critic. In view of the postcapitalist turn of the world, she nevertheless finds in aesthetics, the discipline inquiring into “the sensory equipment of the experiencing being,” a new cause to fight for. Spivak’s argument is certainly subject to debate, but she has candidly pointed out the dilemma among contemporary intellectuals when negotiating “double binds” such as thought versus action, personhood versus collectivity, and poetry and politics. She is not alone, however; scholars such as Martha Nussbaum, Richard Rorty, and Judith Butler have each pondered the role literature and aesthetics play in furthering the reasoning and action regarding public issues.12

When we bring Spivak’s reappraisal of aesthetics and aesthetic education to bear on contemporary Chinese circumstances, what kind of “imagination” can we generate, and how do we play out the “double bind” in our context? Meixue 美學, or aesthetics as a Chinese discipline, was not institutionalized in academia until the turn of the twentieth century,13 as a result of the international circulation of modern knowledge. Since being transposed to the Chinese context, aesthetics has been taken up in association with a wide range of theories, such as Wang Guowei’s reading of the Dream of the Red Chamber through Schopenhauer and Kant, Cai Yuanpei’s pedagogical campaign for aesthetic education in light of Schillerian treatises, Zong Baihua’s promulgation of qiyun shengdong 氣韻生動 (rhythmic play of life and nature) as the essence of Chinese aesthetics in terms of both the I-jing and Hegel,14 and Hu Feng’s advocacy for revolutionary poetics by means of Lukács and Soviet critics such as Lunacharsky.15 These critics have helped not only make aesthetics a humanistic discipline in modern China but also form retroactively a Chinese aesthetic tradition, including pedagogical methods, traceable back to ancient times.

A dogmatic Marxist critic can point out the social and ideological motivations behind such an aesthetic discipline. Peter Button, for instance, takes fictional realism as his case in point and critiques Chinese aesthetics as part of the global aesthetic ideology arising from nascent European capitalism.16 While Button may have raised the right question, the answer he provides betrays nothing but his own “globalizing” intention. That is, he bases his critique squarely on a few Western models,17 showing little knowledge of either the polyphony of Chinese aestheticians throughout the century or any premodern indigenous sources underlying modern Chinese aesthetics. He attempts to promote Cai Yi’s New Aesthetics, a theory known for its deterministic typology of beauty, as the new canon, but succeeds at best in projecting his fixation on socialist Orientalism.

If Spivak’s call for rethinking aesthetics and aesthetic education makes sense for our time, what would a Chinese response be like? One would expect a fairly complex answer to such a question, certainly not limited merely to rehabilitating Cai Yi. This is where we turn back to the lyrical discourse this book has surveyed. I suggest that critiques of lyricism, particularly those since the mid-twentieth century, may serve as a possible starting point. Let me reiterate that I am not equating Chinese lyricism with Chinese aesthetics in toto, nor do I intend to promote it as a universal (global) solution to all Chinese problems. As suggested in the introduction, the Chinese lyrical/shuqing can provide a critical interface for our thought, both because it carries a genealogy of promulgations over time and because it has been in dialogue with various provocations, from revolution to enlightenment, from subjectivity to sovereignty, since the burgeoning moment of modern Chinese aesthetics.

With this argument I introduce in brief the treatises of two contemporary scholars, Li Zehou and Kao Yu-kung, as a way to conclude this book. Both are known for their engagement with modern Chinese aesthetics as well as its Chinese and non-Chinese legacies. More important, both came to highlight the dialectic of qing and shuqing in the late 1970s and 1980s, when China was about to enter a new epoch. Li Zehou was already a rising star in the heyday of Maoism; he gained his fame particularly as a participant in the Great Debate of Chinese Aesthetics between 1956 and 1961, which also involved Cai Yi and Zhu Guangqian. In the debate, which hinged on the fundamental question “What constitutes beauty?”18 Zhu Guangqian tried to modify his idealist stance of the pre-1949 period by suggesting the mediatory process between the perception and reception of beauty, but he never let go of the agency of individual subjectivity, which presumably enacts the process.19 Cai Yi, by contrast, insisted on the extrinsic, objectifiable “typology” of beauty, something to be emulated and realized only through Marxist praxis. Li Zehou takes issue with both Zhu’s subjectivism and Cai’s materialism, proposing that beauty comes into existence through the “sedimentation” of human interactions with nature, which reflects the intelligence and labor of humankind over the progression of history.20

Li Zehou derived his theoretical training from both Kantian and Marxist philosophies. He admires the Kantian claim to human autonomy and judgment and is equally committed to the Marxist tenet of history and materiality.21 In his effort to yoke the two intellectual strains, Li substitutes the former’s a priori claims with a “transformative” and sensorial agenda, and negotiates the latter’s materialist objectivism in terms of human free will and imagination. The result is what Li calls an anthropological approach to the “making” of human civilization. Hence his emphasis on “practical rationality” over rationality, “humanized nature” over nature, “subjecticality” over subjectivity.22

Li Zehou won enormous popularity in the eighties thanks to his reassessment of Kant, his exegesis of the humanistic vein of Marxism, and his reflection on the aesthetic accomplishments of Chinese civilization. The blast of “culture fever” in the aftermath of the Cultural Revolution helped spread his influence. At this juncture, Li set out to proclaim the necessity of cultivating “new sensibilities” (xinganxing 新感性).23 But he did not quite spell out the theoretical premise and historical motivation of these “new sensibilities” until the nineties, when he proposed qing benti 情本體 or the original substance of feeling as the foundation of Chinese humanities.24 By benti Li means neither theological ontology nor Kantian noumenon, but rather the lived Chinese experience that gave rise to the practice and conceptualization of qing as such. Harking back to its philological and philosophical roots, Li conceives of qing as affection, circumstance, or something of a generative nature;25 whether sensuous or abstract in its manifestation, qing is always rooted in this-worldly experience. For him, although qing, or its (not so commensurable) Western counterpart, feeling/affection, has received much less attention than li 理 (reason/rationality) in both the Chinese and Western intellectual traditions, it nevertheless contains a rich repository of inspirations that may help resuscitate contemporary Chinese humanities.

Li proposes that Confucianism offers an elaborate rationale and curriculum of qing: “Confucius pays particular attention to the cultivation of human affection … treating qing as the foundation, substance, and origin of humanity and human life.” Qing helps facilitate ethical relationships and sociopolitical networks, from which emanates the pleasurable sense of beauty. The ultimate manifestation of qing is ren 仁 (benevolence), a state of fiduciary humanity. Li complements his qing with du 度, which means gauge and modulate. As opposed to li or reason, which refers to transcendental intellect, du is related to practical reasoning premised on the sensible and ceaseless reconfiguration of the given circumstance.26 Du always involves imagination and judgment in terms of experiential conditions. In this conjuncture, Li Zehou relates du to the exercise of the Golden Mean, and highlights that it can be nurtured only through aesthetic inculcation, meixue jiaoyu 美學教育 or Bildung.27

For those who were moved by his famous 1986 critique that Chinese modernity is dominated by the twin motifs of enlightenment and national salvation (in the form of revolution), Li Zehou’s subsequent espousal of qing and du may sound like an anticlimax. After all, who would not have wanted a quick fix of China in a more illuminating and “sublime” manner? Li’s turn to qing benti, nevertheless, represents a brave conceptual advance underlined by his personal reflections on history and politics. He has come a long way from the 1950s, when he heroically debated with Zhu Guangqian and Cai Yi in celebration of Marxism. In the aftermath of the Cultural Revolution and the later Tian’anmen Incident, however, he came to realize that the future of new China must not be built merely on repetitive takes of enlightenment or revolution. Through the evocative capacity of qing benti, he hopes to find a way to feel and stimulate Chinese reality, thereby anticipating the remaking of civil subjectivity. Li’s critics may sneer at his ethics and aesthetics of qing as too lofty a project in regard to China’s current status; Li would retort that his project is inspired by and grounded in none other than the sensuous, everyday experience of Chinese life, and that it cannot be implemented too soon. The postsocialist conditions of China, which both the neoleftists and the neoliberals have found undesirable, make Li Zehou’s claim all the more compelling.

Kao Yu-kung first came to engage the polemics of shuqing in recourse to analytical linguistics and formalist criticism. In 1968, together with the linguist Mei Tsu-lin 梅祖麟 (Tsu-lin Mei), Kao published “Tu Fu’s [Du Fu’s] ‘Autumn Meditations’: An Exercise in Linguistic Criticism.” They discuss Du Fu’s masterpiece by analyzing its semantic ambiguity in terms of its lexical and grammatical structure, the rhythmic tension of sound patterns, and its internal complexity of imagery. They announce at the outset that their methodology is “linguistic criticism associated with the names of William Empson and I. A. Richards,” forerunners of Anglo-American formal criticism.28 In the following decade, Kao and Mei offered two more articles on Tang poetry, expanding their methodology from Empson’s formalism to Roman Jacobson’s structuralism.29 Meanwhile, Kao had developed a project of lyrical studies on his own, and his interest quickly extended from poetry to other genres. He declared that “the aesthetics of the lyric are indeed prevalent as the highest literary value in the Chinese tradition,”30 as demonstrated by genres ranging from Sima Qian’s historiography to Zhuangzi’s philosophical treatise and Cao Xueqin’s and Wu Jingzi’s fiction. His study led to his climactic statement in 1985 that Chinese civilization excels in “lyric aesthetics,” which is manifested not only in poetry, particularly regulated verse,31 but also in music, theater, calligraphy, and literati painting. At his most polemical, he considered shuqing/the lyrical as encapsulating Chinese epistemology.32

Kao Yu-kung’s “lyric aesthetics” inevitably reminds one of Chen Shih-hsiang’s “lyrical tradition.” Both Chen and Kao are indebted to the critical tradition of Richards, and both share the conviction of aesthetic subjectivism first made popular by Zhu Guangqian. But Kao is more ambitious than Chen: he not only expands his lyrical vision to all dimensions of Chinese civilization but also develops a comprehensive framework to conceptualize his discovery. Kao describes Chinese lyrical aesthetics as emanating from the mutable dynamics between xin 心 (heart/mind) and the world, which he contrasts with the Platonic episteme of truth versus representation. This vision is best illuminated by lyrical poetry. Perfected in the form of regulated verse, the genre registers the poetic subjectivity’s introspective and reflective absorption of inner and outer experience, as well as its capacity to encode the experience in a form suggestive of both the “centripetal” and “centrifugal” movement of the heart/mind. The result, Kao claims, is an intricate interplay of “internalization” and “symbolization.”33

Kao’s analysis could not sound more formalist at first; he tries to describe, even prescribe, the mechanism of the lyrical mind at work. But he notes that the “lyrical” under treatment has to do with the articulation of the slippery entities of “self” and “present.” How to approximate the “private” and the “fleeting” moment of time in linguistic and other medial terms, how to bring the lyrical to bear on the flux of history and nature, and how lyricism can work itself out in a circuit of perception and reception constitute the fundamental questions. When he indicates that “some can attain a level of contentment or enlightenment [or lyrical vision] only through an experience which touches the recesses of their unconscious mind,”34 he gives his formalist survey a heuristic, phenomenological conclusion.

It is easy to see the difference between Li Zehou’s and Kao Yu-kung’s approaches. Whereas Li looks into the “sedimentation” of human sensibilities that entails aesthetic manifestation and the involvement of tools and labor in any artistic formation, Kao focuses on the epiphanic instant through which the mind and the world interplay with each other in the most suggestive manner. As far as lyrical representation is concerned, Li stresses the overdetermined condition of production; Kao directs his attention to the highly intensified moment of inception. Li is concerned about qing arising from relational intersubjecticality; Kao ponders shuqing as an exclusive form of individuation. Whereas Li’s mixture of Kantian, Marxist, and Confucian thought smacks of postsocialist synergism,35 Kao’s inclination to formalism cum phenomenology shows an attempt to bracket history.

Nevertheless, despite their differences in theory and methodology, Li’s and Kao’s endeavor to address qing and shuqing suggests a shared agenda. As the modern century was nearing its end, they ventured to take a less-trodden path in imagining the Chinese future, carrying on where the mid-century intellectuals, literati, and artists left off in projecting a lyrical vision onto history. Kao Yu-kung continues Chen Shih-hsiang’s aborted work of the “lyrical tradition,” expanding its terrain to the arts and endowing it with theoretical rigor. Li Zehou serves as an interlocutor with Průšek, who first claimed that the lyrical constitutes the quintessence of Chinese culture, given the socialist crusade on an epic scale. Li Zehou’s and Kao Yu-kung’s treatises thus bring home the critical and diacritical potential of Chinese lyricism in modern times. Like their mid-twentieth-century predecessors, they prove again that lyricism/shuqing is not an isolated entity but a polemical part of China’s continued exploration of the terms of selfhood and sociality. Particularly, in view of the ongoing debates in China over the twin yearning for subjectivity and sovereignty, “harmonious society” and “Chinese dream,” a critical rethinking of the lyrical in epic time becomes more compelling than ever.

Toward a Critical Lyricism in an Epic Time

To conclude my survey, I turn one final time to the figures studied in the book, reflecting on their legacies and asking if their engagements could shed new light for us in the present. First is Shen Congwen. Shen passed away on May 10, 1988, leaving the following words as his will:

Illuminate the way I think, and understand me;

illuminate the way I think, and know others.36

照我思索,可理解我,

照我思索,可認識人。

These words, originally derived from Shen’s “Abstract Lyricism,” are simple and yet subtle enough to encapsulate the poetics and even politics of Shen’s lyricism. Zhao 照 means both “follow” and, more suggestively, “illuminate” with a Buddhist connotation.37 The “I” may refer to Shen himself, but more likely to the general first-person subjective position. Accordingly, the “I” subjectivity serves as a conduit, effecting both the self-reflective understanding of one’s own identity and a fiduciary knowledge of enlightenment between self and other. More suggestive is the phrase “think” or “imagine” (sisuo 思索),38 which brings to mind the dilemma Shen described on the eve of the Communist victory. In anticipation of the revolutionary shakeup of China, Shen wrote in 1948, “[My experience] of the past two and three decades has been derived from ‘thinking’ [si 思]; but it is bound to start all over again based on ‘believing’ [xin信]” as mandated by the revolution.39 In a way, his upbringing as a native son of the Chu culture hurled him into the unending twists and turns of thoughts and whims. As much as he hoped for the transformation of China, he found it difficult to pledge unconditional belief in any telos.

Beyond cerebral engagement, think/si encompasses a wide range of mental activities, from affectionate attachment to imaginary flight.40 Judging by his literary endeavors, Shen Congwen must have understood si as not only intellectual deliberation but also wensi 文思 (literary thought) or even shensi 神思 (spirit thought), the outburst of imagination. Thus, through the way Shen Congwen engages si or suisuo, we can revisit the following statement of Liu Xie in Literary Mind and Carvings of the Dragon, one of the origins of Chinese literary thought:

The spirit goes far indeed in the thought that occurs in writing. When we silently focus on our concerns, thought may reach a thousand years in the past; and as our countenance stirs ever so gently, our vision may cross ten thousand leagues. The sounds of pearls and jade are given forth while chanting and singing; right before our eyelashes, the color of windblown clouds unfurls. This is accomplished by the basic principle of thought.41

If Shen was thinking so deeply as to let his thought “reach a thousand years in the past” and “cross ten thousand leagues,” little wonder that he should have felt alienated in the socialist quarter he was assigned to inhabit.

“Think/imagine” deeply or “believe” deeply? Shen was not unaware of the “double bind” inherent in his vocation, and his “abstract lyricism” represents an aborted attempt to construe contemporary Chinese literati’s and intellectuals’ relationship with politics. Let us rethink Shen Congwen’s plea in the essay that all thoughts and opinions of intellectuals and literati be appreciated as a lyrical exercise, and that whatever they say and write amount to no more than a lyrical expression occasioned by scene (setting) or circumstance (即景抒情 jijing shuqing). He even suggests that their thoughts and words may as well be regarded as outcomes of daydreams, therefore posing no threat to anyone. Shen could not sound more self-deprecating in regard to his and his peers’ positions and dispositions. But close reading reveals the radical overtone of his essay. Insofar as all thoughts and works of the intellectuals and literati are labeled lyrical, the lyricism thus defined must generate a magnitude of power in both political and affective terms far beyond that defined by conventional wisdom. The notion jijing shuqing, accordingly, suggests both personal sensibility and historical engagement, both artistic figuration and imaginary intervention.

Shen’s dilemma is also the dilemma of the other intellectuals and artists discussed in this book, regardless of their individual and ideological backgrounds. Lin Fengmian remained active throughout his Hong Kong period, from 1977 to 1990. Besides his favorite subjects, nothing seemed to affect him until the Tian’anmen Incident in 1989. The aged painter was so struck by the bloody crackdown that after a hiatus of almost sixty years, at the age of ninety, he created a series of paintings of political motifs. In the series, titled Emeng 噩夢 (Nightmare), is a hellish panorama of corpses and figures in pain and despair, all in protest against the bloodshed.

Another painting is titled Tongku 痛苦 (Agony), as if derived from his work The Agony of Human Beings, created in 1929. The Agony of Human Beings was inspired by the Nationalist massacre of the leftist activists demanding equality, justice, and democracy in the 1927 Communist revolution. Both Nightmare and Agony, ironically enough, were prompted by the Communist massacre of the Chinese people who took to the streets demanding equality, justice, and democracy in Beijing in 1989. If The Agony of Human Beings still suggests a strong adherence to the conventions of European expressionism, the Agony of 1989 moved far beyond that paradigm. His old expressionist strokes, now fortified by the primitivist simplicity of Chinese folk art and the symbolism of Chinese opera, carry his audience into a fractured reality that can no longer be depicted in any coherent language. Thus, Lin concluded his career by proving again that his lyricism had always been rooted in a “state of crisis.”

Feng Zhi reemerged in the eighties too, but he mostly focused on reviewing and editing his earlier works. In 1990, shortly after the Tian’anmen Incident, Feng composed his last poem, “Zizhuan” 自傳 (Autobiography), in which he looks back at the incessant transformation of his life:

In the 1930s, I negated my poetry of the 1920s;

In the 1950s, I negated my work of the 1940s;

In the 1960s and 1970s, I declared that everything in the past was wrong.

In the 1980s, I regretted how many things I had ever negated,

And thus negated all my previous negations.

It is as if I spend my whole life in “negation”;

Even in the negation of negation there exists affirmation.

What on earth should be affirmed, and what negated?

Now it is the 1990s, it takes some sobriety

To realize that the most difficult thing to achieve is “Know thyself.”42

三十年代我否定過我二十年代的詩歌,

五十年代我否定過我四十年代的創作,

六十年代、七十年代把過去的一切都說成錯。

八十年代又悔恨否定的事物怎麽那麽多,

於是又否定了過去的那些否定。

我這一生都像是在“否定”裏生活,

縱使否定的否定裏也有肯定。

到底應該肯定什麽,否定什麽?

才明白,人生最難得到的是“自知之明”。

Feng Zhi presents an ambiguous portrait of himself as undergoing lifelong self-negations. It can be read either as a reflection on his Goethean philosophy of metamorphosis or an apology for his political changeability over the decades. Either way, in a contemplative tone and sober mood, the poet writes as if composing an anticipatory self-elegy. The last lines of the poem, “What on earth should be affirmed, and what negated? …/the most difficult thing to achieve is ‘Know thyself’” paradoxically echoed Shen Congwen’s motto described above.

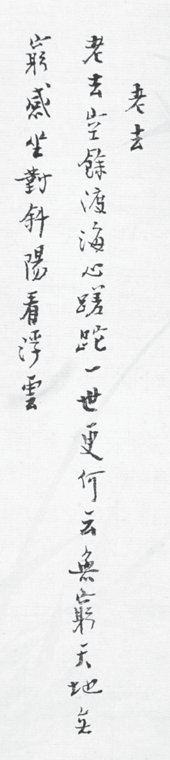

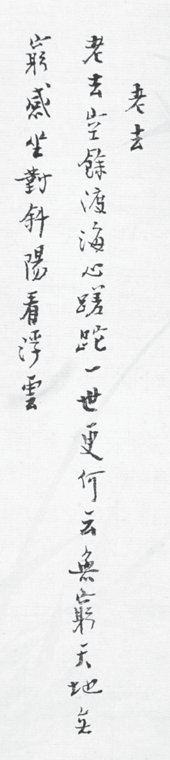

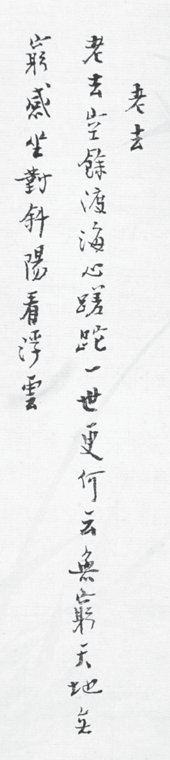

For Tai Jingnong, it was a sense of resignation rather than negation that occupied his mind in his final years. He composed his last poem one year before he passed away in 1990:

I am getting old, left with an empty wish to cross the sea,

having wasted my life, what else can I say?

Boundless heaven and earth, boundless feeling,

facing the sunset, I sit and watch the floating clouds.43

老去空餘渡海心,

蹉跎一世更何云?

無窮天地無窮感,

坐對斜陽看浮雲。

By then Tai had lived in Taiwan for more than four decades. For years he had thought of “crossing the sea” for a homecoming trip, but this wish was never realized due to the antagonism between the two Chinese regimes. When the Taiwan government finally lifted martial law in 1987 and allowed free travel to the mainland, Tai was too old and frail to make the trip. Unlike Feng Zhi, who pondered the dialectic of “knowing” oneself until the end of his life, Tai Jingnong immersed himself in “boundless heaven and earth, boundless feeling.” Having undergone all the ups and downs on the mainland and then on Taiwan as a poet, revolutionary, fiction writer, educator, and calligrapher, Tai came to the point where he made peace with himself by means of poetry.

Hu Lancheng enjoyed a posthumous comeback at the end of the century, thanks partly to the passing of Eileen Chang in 1995 and partly to his personal charm, in writing as in life. As more and more of his writings and biographical details have been unearthed since the nineties, it is no longer an exaggeration to describe Hu as a phenomenon. Among his disciples, Chu T’ien-wen stands out. In her prize-winning novel Huangren shouji 荒人手記 (Notes of a desolate man, 1995), she dramatizes her mentor’s vision of xing and lyrical subjectivism by telling a story about gay life in Taipei. Chu dazzles her readers with her narrative transvestism as well as a baroque parade of (pseudo-)knowledge. However, Chu claims that her writing, however ornate in style, is meant to flaunt the less welcome side of Hu Lancheng’s poetics, about the “erotics” of expenditure and its ultimate transcendence.44 Walking (writing) on the fine line between self-indulgence and self-irony, decadence and redemption, Chu T’ien-wen believes she has best recapitulated Hu’s philosophy of qing and its embodiment in dangzi or the vagabond. But Chu appears too dedicated to her mentor to expound the most treacherous part of Hu’s lyricism, the lyricism of (self-)betrayal.

Tai Jingnong, “Getting Old,” 1990. Courtesy of Mr. Tai Yi-kung

Fei Mu passed away in Hong Kong in 1951, and his name fell into oblivion during the Mao era. Then Spring in a Small Town was rediscovered overseas in the 1980s, and it has since been recognized as one of the best Chinese films ever made. In his recent study of ruins in Chinese art and visual culture, Wu Hung considers the film a most poignant testimony from the mid-twentieth century.45 At the turn of the new century, the renowned “Fifth Generation” PRC director Tian Zhuangzhuang 田壯壯 (b. 1952) undertook to remake the classic, and the result was Xiaocheng zhichun 小城之春 (Springtime in a small town, 2002). Tian’s doppelgänger was meant to be a meticulous homage to Fei Mu’s original, but there are conspicuous differences between the two, ranging from the former’s omission of the mesmerizing voiceover to its streamlining of shots and editing. Above all, Tian reinstates in his remake the sentimental element Fei Mu strove to take out, a decision that baffles many viewers. But Tian may have a point. As if knowing the fate of his quixotic attempt at the outset, he lays bare the sentimental nature of his labor of love, letting himself indulge in ruminations about the past, on and off the screen, and its irrecoverability. Thus, through its arguable failure, Springtime plays out a meta-cinematic pathos: a truncated nostalgia about the original, which, it will be recalled, is about truncated nostalgia.

Moreover, insofar as Fei Mu’s Spring registers the emotional and ethical ruins in the midst of mid-century crisis, Tian Zhuangzhuang’s remake in the new millennium inevitably brings about an allegorical reading of the syndrome of ruination in the postrevolutionary time.46 Another director, Jia Zhangke 賈樟柯 (b. 1970), goes even further in this regard. As Jie Li points out, Jia’s Sanxia haoren 三峽好人 (Still life, 2006) quietly observes the breakdown of human ties as huge demolition projects prevail in the postsocialist era, thereby lending Fei Mu’s aesthetics of “home and nation amid the rubble” an uncanny twist.47

Not unlike Fei Mu, Jiang Wenye was rediscovered by a group of overseas Taiwan musicians and historians in the 1980s, and he became a token figure embodying the diasporic fate of Taiwan. In the 1990s, when the island again went through a series of debates over her identity, Jiang was assigned to a series of predictable roles, as an artist wavering between colonialism and postcolonialism, between nationalism in favor of China and nationalism in favor of Taiwan, and between cosmopolitanism and nativism. Only the Taiwan director Hou Hsiao-hsien 侯孝賢 (b. 1947) came to grasp the lyricism in Jiang Wenye’s music and poetry, its flamboyance and melancholy, its historical pathos and imaginary nostalgia. Hou’s film Jiabei shiguang 珈琲時光 (Café Lumiere, 2003) was inspired by the legend of Jiang Wenye. It tells of a Japanese girl’s futile romance in Taiwan and her renewed resolution to carry on her own life in Tokyo. Café Lumiere is not a biographical movie, but Jiang nevertheless serves as the key metaphor projecting the intertwined affective relationship between Taiwan and Japan. Nothing much happens on the surface of the film, while Jiang Wenye’s music is heard in the background all the way through, a haunting reminder of the endless reverberations of melodies and memories between the past and present.

Back to the case of Shen Congwen. In 1995, his widow, Zhang Zhaohe, wrote an afterword to a collection of Shen’s correspondence from the forties to the sixties; the collection sheds much new light on his thoughts during that time. Zhang writes with regret: “I have never understood him, never completely understood him … why did we fail to discover him, understand him, and support him during his lifetime? … Now all is too late.”48 Indeed, the lyrical mode of thinking of Shen Congwen and his like has been overlooked, if not censored in socialist China, particularly during the era of the Maoist sublime. Will it gain more attention in the new millennium? In view of the recent discourses in China, from “Under Heaven” to datong 大同 (Great commonwealth), from tongsantong 通三統 (unification of three orthodoxies—Confucianism, Maoism, Dengism)49 to wangba 王霸 (kingly hegemony) and “Chinese Dream,” we can sense the popular yearning for, even belief in, the resurgence of a nation in epic grandeur. How can we critically engage these discourses in lyrical terms?

To recapitulate Shen Congwen’s thought in “Abstract Lyricism” more than half a century ago, these discourses, however grand in appearance, derive their appeal from an inherent lyrical call (for harmony, heavenly chain of being, and dream). This lyrical call reminds us of the tender, personal level at which any collective project seeks to exert its spell. It may nevertheless ignite a universalized desire as well as individual whims—a “double bind” indeed. Instead of succumbing to the thrall of these discourses, a vigorous critic in the vein of “abstract lyricism” is able to exercise shensi, an imaginary action that results in no closure but, in Spivak’s words, an incessant “double bind” in engaging the “abstract” and the “concrete,” “the universality of the singular,” and “democracy.” As Shen would have it, once we start to pay attention to the lyrical latitude of a political undertaking, exercising “the displacement of belief onto the terrain of the imagination,” we may better gauge—du, in Li Zehou’s terminology—the relationships between thought (si) and belief (xin), vision and determinism, thereby making a more sensible judgment of history. Accordingly, the challenging task is not to hurry to uphold yet another project in epic terms but to discern and debate the dialectic, the lyrical in epic time.

Above all, the most inspiring “double bind” of the lyrical in epic time is that, however much history is dominated by “actions,” there is another history, the “history with feeling,” that speaks equally if not more emphatically to us. This “history with feeling” either interplays with or, more often than not, merely survives the “history with actions.” But it is this history with feeling that inscribes, deliberates, and abstracts our actions, thus furthering our understanding of xing and yuan, materiality and affection, poetics and politics. This is the history that entertains the multifarious manifestations of Chinese humanities, therefore nurturing a subjectivity that is not bound by immediate beliefs but “reaches a thousand years in the past” and “crosses ten thousand leagues.” This is the history that finds its most powerful manifestation in poetry, in literature.

Resounding are Liu Xie’s words from more than fifteen hundred years ago:

When the sensuous colors of the physical things are finished, something of the feelings (or “circumstances”) lingers on—one who is capable of doing this has achieved perfect understanding.50

物色盡而情有餘者,曉會通也