CHAPTER FOUR

Blooming, Buzzing Babies

All human knowledge begins with intuitions, proceeds thence to concepts, and ends with ideas.

—IMMANUEL KANT,

Critique of Pure Reason (1781), p. 569

WHERE DO BELIEFS come from? I’m with the German philosopher Immanuel Kant on this one. Knowledge generates beliefs, and that knowledge comes primarily from our intuitive reasoning. Let’s examine the evidence. Most adults are so familiar with storytelling from their childhood that we assume that what we know and believe comes from what we were told. However, the picture of the passive child simply absorbing knowledge and beliefs from others, like some sponge sucking up ideas, misses an important point. Children come up with their own ideas long before anyone has told them what to think. Only in the past fifty years have scientists really begun to appreciate how this thinking emerges in the growing child. Let me be clear here, because this is the main argument of the book: children generate knowledge through their own intuitive reasoning about the world around them, which leads them to both natural and supernatural beliefs. To understand this we have to look at the beginning again—not the beginning of culture this time, but the beginning of the developing mind before culture and storytelling have started to play a major role.

The birth of my eldest daughter was a blur for me. As is typical for a first child, the labor lasted a long time, for about twelve hours through the night, and by the time she made her debut the following day around noon, exhaustion, emotion, and sheer anxiety about what was a difficult delivery had ensured that most of my memory of the occasion would be obliterated. Of course, I wasn’t the one doing the hard work. My second daughter’s arrival was much easier. Well, for me at least. This time I was less anxious, knew what to expect, and frankly was more interested in what various professionals were up to and what the machines were for. Maybe I should have been more attentive to my wife’s hardship, but instead I took time to ponder how strange an experience birth must be. I tried to imagine what it must be like to be born—to leave the intimate, warm cocoon of the human womb and enter the sterile, bleached cacophony of a hospital delivery suite, a room flooded with bright light, tubes, cold metal objects, large moving bodies, agitated voices, and machines that go ping. What does the newborn make of all this fuss? It’s enough to make you want to cry.

In 1890 William James described the newborn’s world as a “blooming, buzzing confusion” of sensations.1 No organization or knowledge was thought to be present at birth. On entering the world, we were just a bundle of reflexes and dribbles. Reflexes are those behaviors that are automatically triggered. The pupils in your eyes narrow in bright sunshine because of a reflex. When the doctor taps your knee with a hammer and your leg jerks up, that’s another. No thinking is required. In fact, you can’t stop most reflexes because they are beyond any control or thought.

Babies come packaged with many weird and wonderful reflexes. For example, if you gently stroke the cheek of newborns, a rooting reflex makes them turn their head and mouth to the source of the stroking. They do not know to turn. They are simply wired to do so. There is a sucking reflex when any nipple-sized thing causes babies to pucker up their lips. Clearly these two responses are useful for breast-feeding. There’s a stepping reflex where, if you hold the newborn upright with both feet on a surface, it will alternate lifting and placing one leg and then the next in what looks like walking. This astounds parents, because true walking is at least one year off. Then there is the grasp reflex.

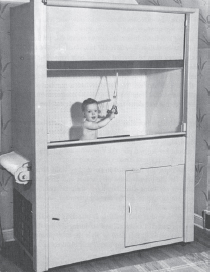

FIG. 5: John Watson demonstrating the strength of the grasp reflex in an infant, dating from around 1919. © JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY.

Their tiny little fingers clamped onto an object placed in their palm are so powerful that you can lift infants off the ground clinging to that object. John Watson and Rosalie Raynor did just this, demonstrating something that no caring parent would dream of trying.2

In the “Moro” reflex—sometimes referred to as the startle response—the baby will fling its arms outstretched, as if to hug you if you drop its supported head backwards or make a loud noise. No one is quite sure what that could be useful for. Some of these reflexes clearly support early adaptive functions, whereas others may be a legacy from evolution that we still carry today. Some argue that the Moro reflex was a mechanism by which the prehominid infant grasped onto the furry underbelly of the mother as she fled in dangerous situations.3 Most modern women with furry underbellies are unlikely to have babies today, but you can still see this primitive response when wild Rhesus monkeys scoop up their babies and scamper when threatened.

As we grow, we lose many of these reflexive behaviors and hold on to others. However, although many of these early infantile reflexes disappear, they are not truly lost, because they can reemerge in adult patients with head injuries, especially if there is damage to the frontal parts of the brain. For example, in a coma many of the higher control centers of the brain temporarily shut down, allowing behaviors like the grasp reflex to reveal themselves.4 This is a fascinating feature of our brains, and it may not be limited to simple reflexes. Maybe as we develop we do not entirely abandon all of our initial behaviors and early thoughts. In this way, the brain may be like the hard drive on your computer. Files are never truly deleted, just overwritten but ultimately recoverable.

BRILLIANT BABIES

Apart from reflexes, it was thought that newborns did not have much in the way of what we would call intelligence or knowledge. However, when scientists started to look more closely, they found that newborns are much more aware of their surroundings than simple reflexes would dictate. More striking was the evidence for learning and memory. My own work (the youngest baby I tested was twenty-three minutes old, wrinkled, and covered in afterbirth, but as bright as a button) revealed that newborns can remember and distinguish between different black-and-white-stripe patterns.5 They also have a preference for faces, as we discuss in the next chapter. This memory for stripes and penchant for faces are something more than simple reflexes could achieve. More amazingly, learning does not begin at birth. For example, if you get pregnant mothers in their third trimester to read aloud passages from Dr. Seuss’s The Cat in the Hat, their unborn babies can hear and remember this experience. When they are born, if you stick a rubber nipple in their mouth to measure their sucking, they will stop when they hear a tape-recording of their own mother reading the same passages. The only way they could have heard this was from inside the womb.6 Learning clearly takes place before birth. The unborn fetus is listening in on the world and can even remember the theme tune to the TV soap opera that Mom watched during the last months of pregnancy. In one study, the particularly irritating (sorry, memorable) theme tune for the Australian soap Neighbors got stuck in babies’ heads as much as it did in adults’ heads.7 So be careful what you say. When two pregnant women are talking, there are four individuals listening in on the conversation.

Within a year, most babies can have a conversation with their parents, share a joke, and begin wondering why people do the things they do. They babble, gesture, exchange glances, tease, mimic, and basically become sociable little members of the human race.8 This transition from the wrinkled newborn in the delivery suite to the socially savvy twelve-month-old is one of the most amazing transformations in life. Something very smart and very fast is happening. We may think computers are smart, but they are nothing in comparison to what a human infant can achieve over twelve months. It is only since engineers started to build computers that we have come to fully appreciate what being smart really is. All the simple things that babies excel at in their first year are some of the hardest problems that engineers have been trying to solve for decades; voice and face recognition, reaching and grasping, walking, reasoning, communication, understanding that others have minds, and even exhibiting humor. All the rudiments of these complex abilities can be found in human infants before their first birthday.

Fueled by the latest research, many parents in the West have come to regard their babies as miniature geniuses, born with unlimited abilities to think and learn. There is now a whole industry of preschool learning and education that taps into the parental desire to give children the best start in life. By “the best start in life” what we actually mean is to make sure that our offspring are smarter than the next kid. As they choose among products with names like “Baby Einstein,” “Baby Bach,” “Baby Da Vinci,” “Baby Van Gogh,” “Baby Newton,” and “Baby Shakespeare,” I think that parents’ expectations are being somewhat unrealistically raised. In fact, a 2007 study of baby videos and DVDs found that they are associated with impaired language development, a report that infuriated the Walt Disney Company, which owns “Baby Einstein.”9

Parents are easy pickings for those willing to sell them products to enhance their child’s future earning potential. We buy black-and-white mobiles to hang over our baby’s crib to stimulate the visual areas of the brain (not necessary), chewable toys with bells inside to enhance eye-hand coordination with multi-sensory input (not necessary), Mozart tapes to improve concentration (myth), flash cards to teach the baby to read (unlikely), and DVDs for the baby to goggle at for hours on end to feed its information-hungry brain (not necessary).10

Like gardeners nurturing little plants, we have developed a “hothouse” mentality to parenting. It’s mostly a Western obsession that has more to do with aspirations for our children’s success than hard science, but every caring parent is vulnerable. Even my wife, a highly educated medical expert, could not resist the urge to buy the black-and-white mobile.11 Yes, babies stare at them. They’re very noticeable—in the same way that anything black and white is noticeable—but such patterns are not going to accelerate normal growth.

Parents have been cajoled into thinking that natural abilities need a helping hand—or worse, that they can be made better than nature originally intended. Of course, environment is important, but you would have to raise a baby in a dark cardboard box with very little input to produce the sorts of long-term disadvantages that most parents worry about.12 A normal world with people chatting away, offering attention and affection with food and the occasional toy to play with, is sufficient for nature’s program to unfold. So if you are a first-time parent or grandparent, relax and chill. There is no need for concern when it comes to infant development. It will take care of itself in an ordinary loving household. If a child develops a problem, it’s not going to be due to a lack of parental care in a typical setting. It takes severe deprivation to alter the program of normal development. Any concern about understimulation from the environment simply reflects how little we appreciate the complexity of the day-today existence that we take for granted.

The image of the brilliant Einsteinian baby was shattered by the following shocking report published in 1997.

Study Reveals: Babies Are Stupid

LOS ANGELES—A surprising new study released Monday by UCLA’s Institute For Child Development revealed that human babies, long thought by psychologists to be highly inquisitive and adaptable, are actually extraordinarily stupid.

The study, an 18-month battery of intelligence tests administered to over 3,500 babies, concluded categorically that babies are “so stupid, it’s not even funny.”

According to Institute president Molly Bentley, in an effort to determine infant survival instincts when attacked, the babies were prodded in an aggressive manner with a broken broom handle. Over 90 percent of them, when poked, failed to make even rudimentary attempts to defend themselves. The remaining 10 percent responded by vacating their bowels.

“It is unlikely that the presence of the babies’ fecal matter, however foul-smelling, would have a measurable defensive effect against an attacker in a real-world situation,” Bentley said.

The report went on to reveal that in comparison to dogs, chickens, and even worms, babies also performed the least adaptively when left on a mound of dirt in a torrential downpour. While the other creatures sought cover, the babies just lay there gurgling.13

When I last checked, there was no UCLA Institute for Child Development, and I doubt there ever will be following this spoof article written for the satirical publication The Onion. These are not the sorts of experiments that scientists conduct on babies, though after reading in the last chapter about John Watson’s terrorizing of Little Albert, you might be forgiven for thinking that such experiments are not beyond the realm of possibility. Of course, babies cannot defend themselves from attack with a broom handle. They don’t need to. That’s what parents are for. They are the ones wired to protect their offspring from attack. The article is lampooning the 1993 cover feature for the now-defunct Life magazine, “Babies Are Smarter Than You Think.”14 The cover title went on to proclaim, “They can add before they can count. They can understand 100 words before they can speak. And, at three months, their powers of memory are far greater than we ever imagined.” Babies may not be able to defend themselves from a broom handle attack, but when it comes to brainpower, they are deceptively smart. Of course, you would be hard-pressed to recognize this. Babies seem so helpless, and yes, you would think that any creature lying there in the mud and rain is pretty dumb, but you would be wrong. In comparison to a collection of chips, circuits, and transistors, as the computer scientist Marvin Minsky graphically put it, that helpless child is the most amazing meat machine on the planet.15

INVISIBLE IDIOTS

It is reported that during the cold war of the 1960s the American CIA was developing machine speech recognition to translate English into Russian and back again.16 According to the story, on the debut test-run of one system, the head of operations decided to try out the common phrase “Out of sight, out of mind.” The computer translated this into Russian, in which it became “invisible idiot.” “Out of sight” is indeed “invisible,” and “out of mind” could mean an idiot. Similarly, “The spirit is willing, but the flesh is weak,” came back as “The vodka is okay, but the meat is rotten.” These translations make sense literally but bear very little resemblance to the meaning of the phrase in the original language, and they remind us that human understanding requires a conceptual mind, one that can think of ideas and reason over and beyond simple input. As with the colorless green dreams of Noam Chomsky that we encountered earlier, our minds contain information that helps us interpret and make sense.

Even at the basic input stage, our stored knowledge helps us interpret the world. For example, if I were to ask you, “Do you wreck a nice peach?” I expect you would look at me quizzically. Now, if you ask this question out loud rather than reading it, you hear and understand it as “Do you recognize speech?”, not as an inquiry about whether you are inclined toward destructive acts aimed at pleasurable juicy fruits. You hear one interpretation and not another. This is because destroying a peach is not a common phrase or idea that we entertain. In the same way that we saw the illusory square in chapter 1, our stored knowledge helps us hear and interpret such ambiguous input. We hear one sentence and not another. Where does this knowledge come from? It seems such an obvious answer that knowledge must come from the world of experience. Everything you know must be learned. But is it as simple as that?

Most people are familiar with the blank-slate metaphor that was originally popularized by the British philosopher John Locke in the eighteenth century.17 The idea is simple enough—children are born without knowledge, and experience shapes them by writing on their minds as though they were blank sheets of paper. Other philosophers, like Descartes and Kant, pointed out that something has to be built in, otherwise it would be impossible to extract knowledge from a cluttered world of experience.18 The brain is more like a biological computer that has an operating system we call the mind. That operating system tells us what to pay attention to and how to process information. Without the right operating system, you can’t make sense of input—like listening to a foreign language and being unable to understand a word of what is said. Where would you begin? How would you know what you were looking for without some plan? It’s like trying to build a house without foundations—you need some embedded structures in the ground to make it stable. The same is true for knowledge. You need rules built in from the start to anchor the information.19 In other words, you need to be born with some form of mind design. How else would you get beyond James’s “blooming, buzzing confusion”?

AT THE SOUND OF THE DINNER BELL

For many years the importance of mind design was largely ignored in Western psychology. This was partly because in Russia, at the turn of the twentieth century, Ivan Pavlov, working on the physiology of digestion in dogs, stumbled on something that every dog owner knows. Dogs begin to salivate just before you bring them their food. Pavlov called this “psychic secretion,” because it was a reflex behavior that seemed to be triggered before food was delivered. Dogs are not psychic. They simply learn when dinner is coming by noticing clues such as the sound of the electric can opener in the kitchen just before food arrives. This seems so trivially obvious today, but Pavlov recognized a really important discovery when he saw one—so important that he was awarded a Nobel Prize for it. He realized that animals could be trained to anticipate reward on the basis of cues. By pairing the sound of a bell with food that naturally causes dogs to slobber, eventually the dogs learned to associate the sound of the bell alone with the impending arrival of dinner. On hearing the bell, the dogs began to drool. It may be my overactive imagination, but I seem to remember a similar response in my old school playground when the bell sounded for lunch. The ringing was enough to make mouths salivate and stomachs rumble.

Pavlov had discovered “conditioning,” a mechanism that would become one of the bedrocks for a whole theory of learning based on association. The idea was that all learning is simple association of events in the environment, like a complex pattern of standing dominoes all stacked up and ready to fall. If you push one over, the others fall in a chain reaction. One event simply triggers the next because of the way the pattern has been formed by association. You do not need to think about a mind making sense of it.

This theory, which provided a way of explaining how babies learn, would dominate Western psychology for the next fifty years. By simply controlling the environment, it was thought that any behavior could be described and predicted without bothering to know what was going on inside the head. The theory became known as “behaviorism,” and those who followed it treated the mind as a “black box” that was not only unopened but also ignored. Minds were irrelevant when all behaviors could be described by a set of simple learning rules that created the patterns of mental dominoes.

One of the staunchest early advocates of behaviorism was our old friend John Watson. When he was not tormenting Little Albert, dangling newborns from pencils, or making out with his graduate student, Watson famously boasted:

Give me a dozen healthy infants, well-formed, and my own specified world to bring them up in and I’ll guarantee to take any one at random and train him to become any type of specialist I might select—doctor, lawyer, artist, merchant-chief and, yes, even beggar-man and thief, regardless of his talents, penchants, tendencies, abilities, vocations, and race of his ancestors.20

By applying the learning rules of reinforcement and punishment, you can shape patterns of behavior. If you want to encourage behavior, give a reward, and an association will be strengthened. If you want to discourage behavior, give a punishment, and the association will be actively avoided. By linking together chains of behavior through punishment and reward, it was claimed, the laws of associative learning can shape any complex pattern, be it personality, skills, or even knowledge.

These laws were even believed to explain supernatural thinking. In what was one of the first experiments in irrational behavior, the Harvard behaviorist B. F. Skinner described in 1948 how he trained pigeons to act superstitiously.21 He achieved this with a laboratory box that was wired to give out rewards randomly. For example, if the bird happened to be pecking at some part of the cage when a pellet was delivered, it soon learned to repeat this behavior. Skinner argued that this simple principle could explain the origins of human superstitious rituals. Like pigeons, tennis players and gamblers seek to reproduce success by repeating behaviors that happened at the time of a reward. Behaviorism explained how something that had long been regarded as a product of feeble thinking could be understood as a consequence of the random reinforcements that the environment occasionally tosses out.

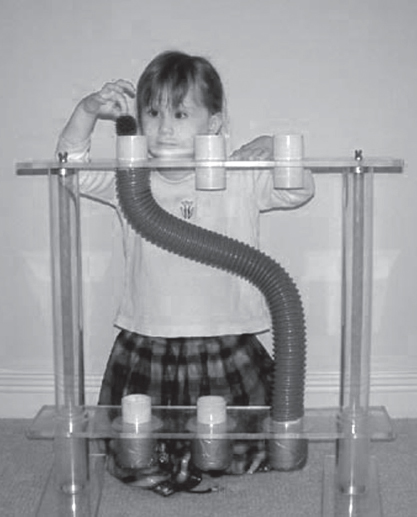

Skinner would go on to claim that all aspects of child development can be explained by associative learning. He was even accused of taking this too far when he was featured in a 1945 Ladies’ Home Journal article with his infant daughter, Deborah, pictured inside what looked like a giant box similar to the ones Skinner had used to train his animals.

FIG. 6: Deborah Skinner in her father’s “Air-Crib,” Skinner’s baby crib, in 1945. © LADIES’ HOME JOURNAL.

Actually, the box was a special thermostatically controlled crib he had designed for infants so that they did not have to wear baby clothes. In the article, he described the benefits of the “Air-Crib” as a labor-saving invention that simplified a young mother’s life and improved baby welfare. That did not stop the urban myth that circulates today of Skinner raising his own daughter like a laboratory rat.22 This reputedly led her to grow up psychotic and commit suicide by blowing her brains out in a bowling alley in Billings, Montana, back in the 1970s. Apparently that is a lie. In 2004 Deborah Skinner Buzan wrote an article in The Guardian refuting that she had ever been to Billings, Montana.23

However, Skinner did go too far with his theories. In the same way that superstitions and rituals emerge, Skinner used behaviorism to explain the uniquely human capacity for language. He proposed that babies acquire a language by a long process of learning words by association, encouraged by their parents to link them together in the appropriate manner. However, when Skinner came to publish these ideas in a book in the 1950s, scientists had already begun to change how they thought about the mind. Behaviorism might have been fine for explaining how the behavior of pigeons and people can be shaped, but not all human abilities can be taught. This change, known as the “cognitive revolution,” was to become a revolution in thinking.24

Skinner was a Harvard heavyweight, but it was a young upstart linguist from down the road at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology who lit the fuse by writing a review of Skinner’s book that would go on to become more famous than the book itself. That upstart was none other than Noam Chomsky. Using language development as his test case, Chomsky launched an attack on behaviorism. He pointed out that no association theory of learning could explain how every human child acquires language through learning for the simple reason that the rules that generate and control language are invisible to every natural speaker (unless you are a linguist, of course). Linguists had demonstrated that all the languages of the world share the same deep structures that are hidden from most of us. There is something in our mind design, Chomsky asserted, that we are not privy to but that we can tap when we need to communicate, and this is known as the universal grammar—the invisible laws that govern how language works.

If universal grammar is invisible and most of us are idiots when it comes to linguistics, how can we possibly teach our children by reinforcement and punishment? How can every child acquire language with these hidden rules at roughly the same time, at roughly the same pace, and with little evidence that associative learning plays a role? Something has to be built into the brains of all children that helps them learn language. Chomsky’s rapier-like attack dealt a fatal wound to behaviorism from which it would never really recover.

OUT OF SIGHT, OUT OF MIND

The cognitive revolution that took place in the United States did not really happen in Europe, largely because the mind had always been so central in European psychology. In adult psychiatry, Sigmund Freud talked about a fragmented mind in constant conflict with itself. In pattern perception, the German Gestalt School we met earlier, with its meaningful structures and organizations, put the mind at the forefront of human abilities. In the United Kingdom, we had Sir Fredrick Bartlett at Cambridge describing memory as a set of active mental patterns, constantly changing and shifting. But it was in theories of child development that the mind took center stage as the focus of interest, and no more so than in the theories of the Swiss child psychologist Jean Piaget.

Like Locke, Piaget also had a blank-slate view of newborns, but he thought that they possess learning rules in their tiny minds that enable them to construct knowledge from the apparently simple act of play. Learning and knowledge emerge as the child discovers the nature of the world around him in a gradual sequence of revelations. Every simple act of playing with objects—batting them, grasping them, sucking them, pushing them off the high chair—is a mini-scientific experiment for infants, the results of which help form the content of their minds.

Piaget believed that from the start young infants do not understand the world as made up of permanent, real objects but that they treat the world as an extension of their own minds. As though having a bizarre vivid dream, Piaget claimed, infants cannot tell the difference between reality and having a thought. Their world is like the world depicted in the sci-fi blockbuster The Matrix, in which evil computers keep the human race in a state of virtual reality by directly feeding experiences into their brains.25 The computers create the illusion of a normal world. In truth, all the humans are captives, harvested for the energy they produce but completely unaware of their true predicament or surroundings. They are unaware of the external reality that exists outside their minds. In the same way, Piaget’s newborns are oblivious to an external reality. They have no concept that the sensations and perceptions they experience in their minds are generated by a real, external world that continues existing even when the baby is asleep. So if some object is really out there, but out of sight, as far as the infant is concerned it does not exist. “Out of sight, out of mind” became Piaget’s signature slogan for this extreme view of the young infant’s failure to grasp the permanence of reality. A true understanding of external reality is something babies have to discover for themselves, he claimed, and to do this they need to get interactive.

SEARCHING FOR THE MIND

Somewhere around four to five months, babies get good at reaching and grasping objects.26 It soon becomes a compulsive behavior that they just can’t stop themselves doing. Any graspable object within reach will do. When my oldest daughter was about this age, I used to carry her on my back in one of those papoose baby holders that leaves their little legs dangling but their arms free to stretch out. When she was not pulling my ears or hair like some demonic monkey on my back, she was always trying to grab anything that came within reach. One day in a supermarket, unbeknownst to me, she reached out and grasped a polythene bag that was hanging from a roll next to the fruit aisle while I was preoccupied with selecting the best apples. I continued walking down the aisle, unaware that I was trailing thirty feet of bags before the smirks of other shoppers alerted me to the growing train of plastic bags behind me.

This fascination with grasping objects is something that Piaget recognized as really important. It means that babies are starting to take an interest in their surroundings. The baby is actively engaging the world. Yet the young infant still does not understand that reality is something different from their mind and independent of their actions. Piaget came to this bizarre conclusion by watching his own young children at play and noticing something peculiar that was to become one of the most famous and studied phenomena in infant psychology. You can repeat this demonstration yourself if you happen to have a six-to eight-month-old infant at hand.27

Take one baby and place a graspable object in front of him. So long as he is not already holding something, he will automatically reach out and pick it up, and then jam it in his mouth for taste evaluation. Now unclasp the object and repeat the procedure, only this time quickly cover the object with a cloth and momentarily distract the infant by snapping your fingers. Hey presto! It’s gone. It’s the easiest magic trick in the world. Most babies will stop and then look around as if the object has disappeared. They do not search underneath the cloth for it. They may pick up the cloth, but rarely as a way of retrieving the object. Because it is out of sight, it is literally out of mind. It no longer exists.

When infants do search under a cloth, a few months later, they still do not understand objects as separate from themselves. For example, if you hide an object under a cushion, a ten-month-old baby will look for it there. But if you then hide the object at a new location in full view of the baby, she will go back and search under the original cushion. The baby believes that his own act of searching will magically re-create the object at the old location. Young children behave as though their minds and actions can control the world. Only through experience do they begin to appreciate the true nature of reality as separate.

MAGICAL BABIES

As it turns out, Piaget was wrong about “out of sight, out of mind” for babies. We now know that they don’t think magically about physical objects. They are not deluded in thinking that their own thoughts make physical things materialize. Babies do know that a real world of objects exists out there. You just have to ask the question in the right way—one that obviously does not require language (because you may be waiting all day for an answer) and does not involve searching for hidden objects. How can this be done? Ironically, the ingenious answer involves a bit of magic.

Everybody likes a good magic trick. Why? Because we don’t believe in magic. If we really did think that objects can vanish into thin air, then a conjurer’s illusion would be of little surprise to us. Magic tricks work because they violate our beliefs about the world. They cause us to be surprised, to stare in wonder, to look puzzled, applaud, and then want to see it done again. The same is true to some extent with infants. They may not be able to give a round of applause and demand an encore, but they do look longer at the magical outcome of a conjurer’s trick. You can measure this simply by the amount of time they spend staring at an impossible outcome in comparison to a possible one.

Over the past twenty years, scientists have used this simple principle to reveal the workings of the baby mind.28 If babies look longer at a trick, then they must appreciate that some physical law is being broken. Somewhere inside their heads, there is some mental machinery clanking away trying to make sense of an illusion by paying more attention. For example, imagine you are a baby watching a puppet show. On the stage sits a Mickey Mouse doll. A screen comes down to hide the doll, and then a hand comes stage left to deposit another Mickey Mouse doll behind the screen. How many Mickey Mouses (or should that be Mickey Mice) are there behind the screen? Easy, you say, there are two. But when the screen is raised revealing three, you know something is amiss. The same is true for babies. They look longer at three dolls. They also look longer when only one doll is revealed, but not when there are two. They know one plus one equals two. By five months of age, babies have the basics of mental arithmetic.29

Hundreds of experiments have shown that babies can reason about similar unseen events in their head. They can think about hidden objects, where they are, how many there are, and even what they are made of. Where does this knowledge come from? Many such experiments show sophisticated and rapid learning that has led Harvard infant psychologist Liz Spelke to propose that some rules for object knowledge must be built in from birth in the same way the rules for learning language are.30 Evolution has provided babies with a set of principles to decode the “blooming, buzzing confusion” that the real world presents to us each time we open our eyes:

Rule 1: Objects do not go in and out of existence like the Cheshire Cat in Alice in Wonderland. Their solidity dictates that they are not phantoms that can move through walls. Likewise, other solid objects cannot move through them.

Rule 2: Objects are bounded so that they do not break up and then come back together again. This rule helps to distinguish between solid objects and gloop such as applesauce or liquids.

Rule 3: Objects move on continuous paths so that they cannot teleport from one part of the room to another part without being seen crossing in between.

Rule 4: Objects generally only move when something else makes them move by force or collision. Otherwise, they are likely to be living things, which, as you will see in the next chapter, come with a whole different set of rules.

How do we know that these rules are operating in babies? For the simple reason that babies look longer when each of them is broken in a bit of stage-show magic. By applying the principles of conjuring and illusion, scientists have been able to show that young infants have knowledge about the physical world that they must be discovering for themselves. And if they are figuring out the physical world by themselves, then it stands to reason that they must be thinking about other things in the world.

INTUITIVE THEORIES

The things we know best are the things we haven’t been taught.

—MARQUIS DE VAUVENARGUES

The magic trick experiments have revolutionized the way we interrogate babies about what they know. If you think about it, all the different things in the world have properties that make them what they are. Inanimate objects have inanimate object properties. Living things have living thing properties, and so on. If you can set up a magic show that violates properties of each of these things, then you can see if the baby spots the mistake.

In a game called twenty questions, you have to work out the identity of something that another player is thinking about. It starts off with the question, “Is it an animal, vegetable, or mineral?” From there the player has to phrase each question to require a yes or no response. “Is it bigger than a bread box?” “Does it come in more than one color?” If you can guess the identity within twenty questions, you win. An electronic hand-held version called “20Q” won the 2006 Toy of the Year Award from the U.S. toy industry association. It’s remarkable. It almost always can figure out whatever obscure object you might have in mind. People find this amazing, but there again, people overestimate how many different objects they think they know. The reason twenty questions starts with animal, vegetable, or mineral is that this division describes most of the different kinds of things there are in the natural world.

Babies also chop the natural world up into groups of different kinds of things. Not unlike twenty questions, they first decide whether something is an object, a living thing, or a living thing that possesses a mind. From very early on, children reason about the nature of inanimate objects as being different from living things that can move on their own and are alive.31 They also start to see living things as motivated by goals and intentions.32 In other words, they are beginning to think about the notion of what it means to have a mind. Well before young children have been taught anything at school, they are already reasoning about the physical world, the living world, and the psychological one. They are in effect little physicists, little biologists, and little psychologists.33

However, the knowledge they have in each of these areas is more than just a list of facts. Their knowledge of the world is theorylike. What this means is that when babies encounter a new problem, they try to make sense of it in terms of what they already know. This is what theories do. They give us a framework in which to make sense of something. More importantly, theories allow children to make predictions in a new situation. For example, having established that a spoon pushed off the edge of a high-chair tray falls down, the baby will theorize that other solid objects should do the same and will happily explore this by dropping everything over the edge. The baby is beginning to understand the effects of gravity.

Babies also reason about people. Having witnessed that Mom will pick up the spoon and replace it on the table, they theorize that adults are predictable whereas the family hamster is not. They are beginning to understand that actions differ between living things and to appreciate goals and intentions as mental states. From the moment babies start to pay attention and anticipate events in the world, they are forming theories about how the world works. No one has to teach them about gravity or the mind. They are figuring these out for themselves. It is not even clear that they are fully aware of exactly what they are figuring out, but their thinking is not haphazard. These organized ways of thinking are the intuitive theories that all infants develop.34

Most people are familiar with the word “theory” in the context of science, such as Einstein’s theory of relativity or Wegener’s plate tectonic theory of continental drift. These are formal scientific theories that have been worked out, discussed, written about, tested, and argued over by hundreds of educated adults. By contrast, children’s intuitive theories are spontaneous and naive. However, children do share one interesting property with scientists. Both children and scientists are stubborn when it comes to changing their minds.

CAUGHT IN THE GRIP OF A THEORY

Academics love witty titles for their scientific papers. It not only livens up what could be a very dry piece of writing, but it demonstrates that even scientists can have a sense of humor. In a paper entitled “If You Want to Get Ahead, Get a Theory,” Annette Karmiloff-Smith and Barbel Inhelder describe how children appear to reason in a theorylike way when trying to solve everyday physics problems.35 The pun is on getting “a head,” which of course can mean either get an advantage or the bony box that houses our brain. However, the paper also makes a very serious point about the role of intuitive theories in intellectual development.

In their study, four-, six-, and eight-year-olds were given wooden rods of different lengths to balance. Imagine trying to balance a ruler on a pencil. How would you go about it? I bet that you would estimate where the middle of the ruler is and balance it on the pencil at this point, which would be the correct solution. The children also balanced the rods in the middle. However, when given rods that were secretly weighted at one end so that they could not balance in the middle, something interesting happened. Initially, all of the children tried to balance these in the middle, but of course they failed. The eldest children looked confused at first, but then realized something was not quite right. They then shifted the rod until they found the point of balance. The youngest children did not seem surprised by the weighted rods and again found the point of balance by moving the rods until they balanced. In contrast, the six-year-olds failed miserably at the task.

Over and over again, six-year-olds placed the rod in the middle, and every time the rod tipped over. They were so sure that the rods must balance in the middle that they persisted with the strategy until they eventually got frustrated, threw the rods down, and stormed off saying that the task was impossible. They were so convinced by the theory that things balance in the middle that they were unable to see that there might be exceptions. This was their theory of balance, and like stubborn adults who refuse to abandon ideas when they are proven wrong, they were unable to be flexible in their behavior.

Unlike six-year-olds, the younger children did not have any theory or expectations. They just approached and solved the problem through trial and error. The older children had a theory and also predicted the rods should balance in the middle. However, on discovering this was not so, they had the mental flexibility to realize that sometimes there are exceptions in life. The inflexible six-year-olds were caught in the grip of a theory.

Ten years ago, I discovered a similar phenomenon.36 Imagine a flexible tube like the one on a vacuum cleaner. Now imagine the tube connected from a chimney to a box below. If I dropped a ball down the chimney, you would know to search for it in the box. You would predict that the ball would fall down the tube into the box. Now imagine that I put a bend in the tube so that the box is not directly below the chimney anymore. If I drop a ball down the chimney, where would you look for it now? In the box of course, because the box is connected to the chimney. What could be easier?

FIG. 7: The tubes apparatus. Children typically search directly below. AUTHOR’S IMAGE.

Remarkably, this is something that preschool children find difficult. They search for the ball directly below. They will search underneath over and over again, even though you can show them each time that it is in the box connected to the chimney by the tube. What’s going on?

This weird “gravity error” reveals some interesting things about the minds of young children. The first is that they reason in a theorylike way. They try to apply the knowledge they already possess to make sense of and predict what might happen next. Just like reticent old scientists, they don’t want to believe the evidence when it conflicts with what they expected. All that practice with pushing things off the high chair as an infant has led them to a theory that all objects fall straight down. But when objects don’t behave as expected, young children persist with the theory and think something is wrong with the setup. This is because they have trouble ignoring intuitive beliefs.

Humans share the gravity error with chimpanzees, monkeys, and dogs, which have all been tested on tubes.37 Only dogs seem to learn the correct solution relatively quickly. Are they smarter than young children and primates? Probably not. I think they are more flexible on this task because they don’t hold such a strong belief in falling objects in the first place. They are like the four-year-olds on the task of balancing the ruler—not particularly committed to one solution over another.

Eventually children can learn to ignore the gravity error, but even adults can trip up on it. This brings us back to one of the central points in this book. Early ideas may never be truly abandoned. Consider another example from the world of falling objects. What happens to a cannonball fired from the edge of a cliff? Visualize it for a moment. What path would it take? Most preschool children think that, just like Wile E. Coyote in the Road Runner cartoons, the cannonball would travel forward until it loses momentum and then drop straight down.38 Such beliefs can still operate in adults. If you ask adults what path a bomb takes when dropped from a plane, most of them think that it falls straight down, and they behave accordingly.39 In games where adults have to release a tennis ball to fall into a cup as they walk by, they typically overshoot because they try to release the ball when directly above the cup.40 In both examples, the motion is actually a curve, but our childish, naive straight-down theory still operates. These examples show that intuitive theories are not always abandoned when we become adults. If such naive physical reasoning reveals that childish beliefs lurk in adults, what happens if those beliefs are supernatural?

CHILDREN AS INTUITIVE MAGICIANS

When does supernatural thinking first appear? So far in this chapter I have been describing how infants understand the natural world. This process begins long before education has any role to play. Children chop the world of experience up into different categories of things and events. To make sense of it all, they generate naive theories that explain the physical world, the living world, and eventually the psychological world of other people. While children’s naive theories are often correct, they can be wrong because the causes and mechanisms they are trying to reason about are invisible. For example, no one can see gravity, but you can assume that something makes objects fall straight down if they are released. Or consider an example from biology. We can easily recognize when something is alive. You can tell by how it looks and more importantly by how it moves, but you can’t actually see life in something. All you can do is infer it, and sometimes you will be wrong. Sometimes things do not always fall straight down. Sometimes living things do not move, and sometimes moving things are not alive. When we misapply the property of one natural kind to another, we are thinking unnaturally. If we continue to believe it is true, then our thinking has become supernatural. This is where I think our supersense comes from. Let me unpack this important idea for you further.

Children naturally categorize the world into different kinds of things. If the child is not certain about where to draw the boundaries or misattributes properties from one area to another, the child is going to be thinking supernaturally. For example, if a child thinks that a toy (physical property) can come alive at night (biological property) and has feelings (psychological property), this would represent a violation of the natural order of things. If the child thinks that thoughts can transfer between minds, he is misunderstanding what a thought is and where it comes from. Children who mix up the properties of their naive categories are thinking supernaturally. Inanimate objects that come alive and have feelings are magical. A thought transferring between minds is otherwise known as telepathy.

In hundreds of interviews with children between the ages of four and twelve years, Piaget asked them to explain the workings of the world.41 He asked them about natural phenomena such as the sun, clouds, rivers, trees, and animals. Where do they come from? Do they have minds?, and so forth. What he discovered was recurrent supernatural beliefs, especially in the youngest children. They thought that the sun follows them around and can think. That’s why children paint smiley faces on suns. It’s much more reassuring to think of it as a friendly being who makes summer days pleasant and people smile than as an inanimate ball of nuclear energy that would frazzle us if it were not for the earth’s protective ozone layer. The children Piaget studied believed that trees have minds and can feel. In short, they thought the inanimate world is alive, something Piaget called “animism.” Animism means attributing a soul (Latin, anima) to an entity, and it can be found in many religions as well as in secular supernaturalism. Where do children get these ideas? No one tells them to think like this. It’s just the way the child makes sense of the world.

One reason children make these sorts of mistakes is that they make sense of everything from their own perspective. Piaget recognized that young children are so caught up in their own worldview that they interpret everything in the world according to the way it relates to them. Piaget called this “egocentrism” to reflect this self-obsessed perspective. The sun does appear to follow you around, as it is always there when you look over your shoulder.

Children also attribute purpose to everything in the world by assuming things were made for a reason. The sun was made for me. This is not surprising considering that modern children are immersed in a world of artifacts that have been designed and made for a reason. Young children do not readily make the distinction between things that have been created for a purpose and those that just happen to be useful for a purpose. For example, if I can use a stick for prodding, I may be inclined to see sticks as having a purpose. In other words, sticks exist as something for me to use.

This way of thinking leads the child to what has been called “promiscuous teleology.”42 Teleology means thinking in terms of function—what something has been designed for. This way of thinking is promiscuous because the child over-applies the belief of purpose and function to everything. For example, there are 101 ways to travel down a hillside, including walking, skipping, running, roller-blading, skateboarding, sledding, skiing, trail-biking, Zorb balling, and so on. But no adult would make the mistake of saying that the hill exists because of any of these different activities. Children, on the other hand, say that hillsides are for rolling down and so on.

Most seven-year-olds explain the natural world in terms of purpose. As we saw in the last paragraph, promiscuous teleology may incline the child to view the world as existing for a purpose. That’s why the creationist view of existence is so intuitively appealing.43 Most religions offer a story of origins and purpose, which is why creationism fits so well with what seems natural at seven years of age. Maybe that’s the origin of the Jesuit saying “Give me a child until he is seven and I will give you the man.”

Children are also prone to “anthropomorphism,” which means that they think about nonhuman things as if they were human. It’s easy to see this happen with pets and dolls, which children are encouraged to treat as human. However, children might also think that a burning chair feels pain or that a bicycle aches after being kicked. They imagine how they would feel if they were burned or kicked, and because of their egocentrism, they misapply this view to everything, including inanimate objects.44

Even adults easily slip into this way of thinking. Have you ever lost your temper at an object? Usually it’s one that has let you down at a critical moment. The car that dies on the way to an important meeting or, more often in my case, the computer that crashes when you have not backed up your work. Anthropomorphism explains why you talk nicely, beg, and then threaten machines when they act up. It’s just the natural way to interact with objects that seem purposeful. We know that talking to objects has absolutely no effect, but we still do it.

So the origins of supernatural beliefs are within every developing child. All of these ideas are not new. The philosopher David Hume wrote about mind design and supernatural beliefs and identified the same aspects of mind design more than two hundred years ago. Hume recognized the same childlike reasoning in adults when trying to make sense of the world. Adults too see a world of things that seem alive with human qualities.

There is an universal tendency among mankind to conceive all beings like themselves, and to transfer to every object, those qualities, with which they are familiarly acquainted, and of which they are intimately conscious. We find human faces in the moon, armies in the clouds; and by a natural propensity, if not corrected by experience and reflection, ascribe malice and good-will to everything, that hurts or pleases us. Hence…trees, mountains and streams are personified, and the inanimate parts of nature acquire sentiment and passion.45

From this perspective, we can see how an egocentric, category-confused child is going to hold beliefs that are the origins of adult supernaturalism. To begin, children have difficulty distinguishing between their own thoughts and those of others. A child who has an idea thinks that others also share the same idea. Such a notion would be consistent with telepathy and other aspects of mind-melding. Also, children may believe they can affect reality by thinking, which is the basis for psychokinesis: the manipulation of physical objects by thought alone. Children report that certain rituals, such as counting to ten, can influence future outcomes, which is equivalent to spells and superstitions. They also believe that certain objects have special powers and energies. This is sympathetic magical thinking that links objects by invisible connections. To top it all, children see life forces everywhere. Anyone holding such misconceptions could easily succumb to a supersense. This is why I think that adult supernaturalism is the residue of childhood misconceptions that have not been truly disposed of.

DO CHILDREN REALLY BELIEVE?

Do children realize that their misconceptions are supernatural? Young children do not use or understand the word “supernatural.” Rather, when faced with something inexplicable, they are more likely to say that it is “magic.” What do they mean by this? The word has lost its sinister connotation and is now used in everyday language. From “magic markers” to “Magic Johnson,” the term is synonymous with anything special. In recent years, developmental psychologists have begun to question whether children really do believe in magic. After all, they don’t try to conjure up cookies when they are hungry, and they know their imaginary friends are just make-believe. In one study, preschool children were asked to imagine that an empty box contained a pencil.46 They could do this easily, but they did not actually believe that there was a pencil inside. When another adult entered the room asking to borrow a pencil, the children did not make the mistake of offering them the one that they had imagined in the box.

If adults talk about magic, maybe children are just playing along when asked to imagine magical things.47 After all, what else would we expect them to say if we tell them that we have hired a magician for their magical birthday party who is going to do magic tricks and that all the guests should come dressed as wizards or fairies? Our whole approach to young children is to emphasize magic as part of normal experience. Magic has lost its supernatural meaning.

The Russian psychologist Eugene Subbotsky revealed magical thinking in young children with a simple conjuring trick. He placed a stamp in a box, muttered magical words in his heavily accented Russian, and then opened the box to reveal a stamp cut in half.48 Young children believed that it was the same stamp and that the Russian spell had cut it in half. Older nine-year-olds and adults always said that the stamp must have been switched, while younger children were more gullible. But are adults so sure about the world? Although they thought the whole charade was a trick, they were unwilling to put their passport or driver’s license in Subbotsky’s box. They did not want to risk being wrong.

When the stakes are high, we are less certain of our reason. It would appear that, just like the killer’s cardigan, we consider potential costs and benefits when weighing up the possible unknown. This is why rational students are unhappy to sign a piece of paper selling their soul for real money.49 Only one in five would put their signature to the contract, even though the form clearly stated that it was not legally binding. Rationally, we would expect them to have more courage in their conviction, like the atheist Gareth Malham, who sold his soul on eBay in 2002 to help pay off his $20,000 student debt. There again, his soul only went for a paltry $20, which hardly justified the effort.

Is it really so surprising that young children give magical explanations for conjuring tricks? Maybe they just use magic as the default explanation when they can’t figure something out. What we should find more remarkable is that children grow up in a world full of complex technologies and events that they cannot possibly understand and yet do not talk about them as magic. Remote controls operate machines from a distance. People can talk to others via little hand-held boxes, and so on. The modern child is immersed in a world that would amaze and possibly frighten someone from before the scientific revolution. As Arthur C. Clarke pointed out, “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.”50 So why do children not call everything magic?

Young children may start off as Piaget described, with all sorts of magical misconceptions, but with experience older children become more savvy. Children appreciate that there are some things they know and others they do not. When they see something that violates what they expect, they are more suspicious. But it is not the supernatural thinking of young children that is so remarkable, but the supernatural beliefs of adults who should know better. With experience and understanding, supernatural thinking should decline in children, but there is a paradoxical increase in supernatural beliefs in some cultures. In societies where belief in the supernatural is the norm, it increasingly plays an explanatory role in adults’ reasoning. This is the effect of environment, and this is where religion wields its influence. For example, when the anthropologist Margaret Mead asked Samoan villagers to give an explanation for why a canoe might have broken its mooring in the night, children tended to give physical reasons, whereas adults were more likely to talk about hexes and witchcraft.51 That’s because the adults had become increasingly influenced by the context of culture.

In our culture in the West, most supernatural beliefs, such as those surveyed in the Gallup poll described in chapter 2, are regarded as questionable, even though the majority of people believe at least one. Adults may even deny supernatural beliefs, but as we noted earlier, so long as no one mentions the word “supernatural,” adults are quite happy to entertain notions of hidden patterns, forces, and essences. In the 1980s, researchers interviewing British women in Manchester about their supernatural beliefs found that they had to drop the term “the supernatural,” as this was generally met with negative reactions.52 However, as soon as the term “the mysterious side of life” was used, the interviewees showed decided interest and were eager to talk. These women, mostly retired, happily went on to recount multiple experiences of ghosts, precognition, and feeling the spirits of the dead. They regarded these experiences not as supernatural but rather as mysterious.

We have become increasingly aware that supernatural thinking is something to be embarrassed about. We may even hide our superstitious behavior when there are others around. Three out of four adults will avoid walking under a ladder if they think they are unobserved.53 If they see another adult do it first, they are much more likely to walk under the ladder. If we do not think that we are being watched, we are more likely to act superstitiously. Students were even less likely to cheat when they were told casually that the exam room was said to be haunted.54

Children may not offer an imaginary pencil to an adult, but if left alone, they will check a previously empty box after they have been asked to imagine that it contains ice cream.55 Even though they know it is just a pretend game, they are still not certain that the ice cream did not somehow materialize inside the box. In another study, four- to six-year-olds were told about a magical box that could transform drawings into pictures.56 All children denied that such a magical transforming box was possible. However, several days later all of the children tried out the magical spell when left alone with the box and were clearly disappointed when they opened it to find the same drawing inside. This suggests that children do have some expectation of what is and is not possible but are open to the testimony of others. Here is where storytelling and the role of culture can influence children who are uncertain.

Children may not conjure up cookies, pencils, and imaginary friends, but that may be because they understand the limits of their own abilities. They may be less sure about the extraordinary power of others or mysterious magical boxes. This is where culture steps in to shape our beliefs. Again, others’ testimony becomes important in supporting supernaturalism, and this is particularly powerful on the playground. In one of the largest extensive surveys of beliefs, Peter and Iona Opie studied more than five thousand children of the British Isles. Among the various playground activities of games and songs were a mixture of supernatural beliefs relating to oaths and superstitions. The Opies noted that children distinguished between superstitions that were “just for fun” or “probably silly” and others that were taken as given. Here the Opies noted the presence of the supersense in those practices that were unquestionably accepted:

Others, again, are practiced because it is in the nature of children to be attracted by the mysterious: they appear to have an innate awareness that there is more to the ordering of fate than appears on the surface.57

The other remarkable finding was that children mostly shared the beliefs of their friends but as they became adolescents they increasingly took on the beliefs of their family and elders. The fragmented folklore of children gave way to the traditional beliefs of the culture as they became adults. This may partly explain the pattern of emerging religious beliefs that we saw in the last chapter, where seven-year-olds were mostly creationist in their understanding of the origins of life on earth but older children had started to migrate toward formal religious beliefs or scientific accounts, depending on the family environment.

WHAT NEXT?

So far, the proposal on the table is that the origins of supernatural beliefs can be traced to children’s misconceptions about nature. However, this picture is missing a very important piece of the puzzle. No man is an island. We are social animals adrift in an ocean of people. Modern humans have the scientific name Homo sapiens, or “thinking hominid,” but as Nick Humphrey has pointed out, the label for modern humans is more appropriately Homo psychologicus.58 Most of our brainpower and the skills that separate us from other animals derive from our capacity to be psychological—to assume that others have minds and reason. This is why we are social animals. We have evolved to coexist in groups, to predict others, to communicate, and to share ideas. All of these skills require a mind sophisticated enough to recognize that others have minds too.

Children’s misconceptions may be intuitive and not taught, but they feed into a cultural context to become folklore, the paranormal, and religion. We know that social environments are important in providing these frameworks of belief, but they only exist in the first place because of the supersense. As children discover more about the true nature of the world, they increasingly understand that many of their intuitions are wrong and would only be possible if the supernatural were real. But when others share the same sorts of misconceptions, such beliefs become socially acceptable, despite the lack of evidence or what rational science might say.

In the next chapter, I examine how the supernatural becomes increasingly plausible when we enter the social domain. As Homo psychologicus, our social nature depends on our ability to be mind-readers. Each of us is capable of understanding and predicting what others will think and do because we have an intuitive theory of mind. We understand that other people have minds that motivate what they do and what they believe. In the same way that we have intuitive theories of the physical world, humans also have an intuitive theory of the mental one. However, unlike the physical world, where science can objectively verify our beliefs, the mental world is still one of the greatest mysteries that we all take for granted on a daily basis. What is the human mind? How does it work? How does something that is not physical control a physical body? We rarely stop to ask these questions because the mind is so common. Our minds are who we are. It’s only when we lose them or they become disturbed that we become acutely aware of how mysterious the mind really is. That mystery is fertile ground for a supersense.