CHAPTER FIVE

Mind Reading 101

ONE OF THE supernatural powers that I have often thought would be handy is the ability to read other people’s minds. Imagine what fun you could have knowing what people really thought about each other. You would know who fancied you (if anyone) or which two people were having an illicit affair in the office. It could make you the most insightful judge or considerate seducer. All the secrets that we try to hide from each other would be out in the open. There again, maybe ignorance is bliss and it is better not to know what others think, especially if those thoughts of others are less flattering about ourselves than we would wish.

We can all mind-read to some extent. Not telepathy or Vulcan mind-melding. That’s the stuff of fiction. Rather, we instinctively try to figure out what’s on each other’s minds. Whether it’s winning an argument, negotiating a deal, or serving a customer, all of us recruit our mind-reading skills on a daily basis to infer what others are thinking. We consider what their beliefs might be and guess at which emotions they are experiencing. We want to know “where they’re coming from.” In this way, we anticipate and manipulate others through mind-reading even though we never have direct access to their private thoughts or feelings.

Strangers can read each other’s minds when no word has been spoken. As we watch people go about their business in public places, we automatically attribute hidden purpose to their movements. They seem to have intentions and goals. We imbue them with rich mental lives. That’s because we think they are like us. They too must experience the same anxieties, disappointments, frustrations, elations, and the whole varied tapestry of human concerns that we do. However, our mind-reading is not foolproof. We often misjudge. Nevertheless, it is easier to understand others as beings motivated by minds rather than the unsavory alternative: mindless beings, sophisticated robots, or well-dressed zombies.

Some of us are better at mind-reading than others. The Cambridge psychologist Simon Baron-Cohen has proposed that women are more accomplished at it than men.1 Mind-reading—or social empathizing, to be more accurate—is a female skill resulting from a brain designed to be social. Men, on the other hand, are poor empathizers, but really good at cataloging CD collections. According to the theory, women are good at empathizing, whereas men are better at systemizing. It’s a controversial idea and deeply “un-PC,” but it does seem to fit with much common sense.

Our mind-reading is intuitive. No one teaches us, and we start using it before we can even speak. Like language, it’s one of the things that make us human. This is because understanding other minds is so critical to the way we get on with each other. Homo sapiens may have evolved to think, but most of those thoughts are about other people. In this chapter, we examine the emergence of mind-reading in our first important relationship with our parents, and in particular our mothers. During these formative years, babies and adults engage in increasingly complex social exchanges. Are you hungry? Do you need your diaper changed? What’s she doing? What does he mean? Second-guessing each other is the art of mind-reading, and babies become expert over the early years, better than any other animal.2 They do this by understanding that bodies are motivated by minds. This understanding equips them for the more challenging role of understanding the social world of others outside the family circle. However, in becoming sociable mind-readers, children start to think about how minds are separate from bodies. That thinking prepares the ground for some very strong supernatural beliefs about the body, the mind, and the soul.

LET’S FACE IT

Our mind-reading starts with the face, and reading the eyes in particular. What do supermodels like Naomi Campbell and Kate Moss, Japanese Manga cartoon characters, and babies all have in common? My, what big eyes they have. One of the reasons we find supermodels and Manga characters so cute is that they remind us of babies. This quality is called “babyness.” It’s simply the large size of eyes relative to big heads on small bodies.3 Biologists noticed that the young offspring of many mammals share this babyness feature. Puppies, bunny rabbits, and Chihuahuas are all good examples of animals that excel at babyness. It is particularly noticeable in apes because of their large heads, which are needed to accommodate their big brains. However, babyness is more than just a quirk of physical dimensions. For example, if you ask children who have not yet reached puberty to rate faces for attractiveness, they prefer adult faces to baby faces.4 However, when they hit puberty, girls, in contrast to boys, show a marked reversal by preferring babies to adults. In this way, nature is beginning to pull the strings that shape our reproductive behavior.

Faces are like magnets to babies. They can’t keep their eyes off us. If you measure their eye movements to see where they are looking in a busy social scene, they are checking out the faces of the other people in the room. This interest in faces begins at birth.

FIG. 8: Newborns stare longer at the face image on the left. AUTHOR’S IMAGE.

For example, given the choice, newborn babies will look longer at the pattern on the left compared to the one on the right.5 The one on the left looks more like a face than the other, which is identical but upside down. The fact that this is found in babies who have had little experience of faces supports the theory that humans are born to attend to anything that looks like a face. Some argue that this reflects an evolutionary adaptation to make sure babies pay attention to their mother’s face in much the same way that young baby birds instinctively follow the first moving thing that resembles an adult as soon as they hatch.6

So faces are particularly important to humans. We can distinguish and remember thousands of faces, and yet the differences between individual faces can be so small. As we discussed in chapter 3, the fusiform gyrus of the brain (the area just behind your ears) is active whenever you look at faces.7 However, if you are unfortunate enough to suffer damage to your fusiform gyrus, you can lose the ability to recognize individual faces. The resulting disorder, known as prosopagnosia, can even produce a loss of recognition of one’s own face in the mirror.8

All this brain machinery dedicated to faces may explain why we are hardwired to see faces when there are none, and often in the most unexpected places. Dr. J.R. Harding, a radiologist in Wales, told me about the case of a man who had an undescended right testicle.9 This condition is common and usually identified during routine screening around the time a boy reaches puberty. Which reminds me of my own experience. I am not sure how the screening is done today, but in my time, before informed consent, most of us prepubescent boys were left completely terrified and perplexed as to why the school nurse asked us to cough as she cradled our scrotums.

When Dr. Harding examined the image of the man’s descended left testicle, he nearly fell off his seat when he saw what was clearly a face. He wrote the case up and published a medical paper entitled “A Case of the Haunted Scrotum” for a bit of fun, which became his “least important but most celebrated contribution to radiology.” In the report, Dr. Harding offered an explanation for the absence of the second undescended testicle: “If you were a right testis, would you want to share the scrotum with that?”

Facelike appearances can readily be found among natural and artificial objects. Boulders, knotted tree trunks, and Volkswagen Beetle cars can all look like they have faces. Because faces are so important, we tend to treat their appearances as auspicious. We think of such appearances as more than just coincidences. In his book Faces in the Clouds, Stewart Guthrie argues that our intuitive pattern-processing biases us toward seeing faces, which leads us to assume that hidden agents surround us.10 Building on David Hume’s “We find human faces in the moon, armies in the clouds” observation that we encountered in the last chapter, Guthrie presents the case that our mind is predisposed to see and infer the presence of others, which explains why we are prone to see faces in ambiguous patterns. If you are in the woods and suddenly see what appears to be a face, it is better to assume that it is one rather than ignore it. It could be another person out to get you. Seeing faces leads to inferences of minds. Those minds may have malevolent intentions against us. Why else would they be hiding in the shadows? Such a bias could be just one of the mechanisms that support a sense of supernatural agents in the world. This probably accounts for why face apparitions are often taken as evidence of supernatural activity. For example, the online casino Goldenpalace.com bought a decade-old toasted cheese sandwich said to bear the image of the Virgin Mary for $28,000,11 and the face of Jesus has appeared on several baby ultrasound scans of pregnant women.

FIG. 9: “The Haunted Scrotum.” Face image discovered by Dr. Harding. PHOTO © RICHARD HARDING.

LOVE IS THE DRUG

Faces may be the initial patterns that draw our attention, but it is the emotional experience during intimate moments with those we care about that creates a tangible sense of connectedness. For example, most newborn babies look like grumpy old men with wrinkled skin and bald heads, but to parents these miniature old codgers are beautiful. Mothers can’t help falling in love with their babies because nature has slipped them a Mickey Finn cocktail of hormones that forge a passionate bond. Fathers feel it too, but deep down nature really intended this to be a mother–baby thing. It’s not as if mothers have a choice. Their bodies are awash with chemical messengers controlling their emotions and behavior.

One chemical is the oxytocin that surges through the mother’s brain around the time of birth to trigger the uterine contractions. It’s also active during breast-feeding. Outside of mothering, oxytocin is stimulated by the physical contact of sex. It’s no surprise then that research has revealed that oxytocin plays a role in social bonding. Weirdly, we know this because of two species of vole. Prairie voles engage in an intense twenty-four-hour courtship, after which they mate for life. On the other hand, their almost genetically identical cousins, montane voles, are promiscuous and have a preference for one-night stands. They do not pair-bond for life. One explanation is that the reward center in the brain of prairie voles is sensitive to oxytocin, whereas the same center in montane voles is not.12 Oxytocin gives prairie voles that loving feeling because their reward centers are satiated when they mate, but this doesn’t happen in montane voles. As Mick Jagger sings, they can’t get no satisfaction. When sex scientists blocked reward pathways in the prairie voles, they too became promiscuous with female partners. They did not stick around in the morning or return calls. However, when an injection of a love cocktail including oxytocin was administered to prairie voles, it worked like cupid’s arrow, and they bonded again. You could say that those of us who fall deeply in love are behaving just like prairie voles.

When we say the chemistry is just right between two people, there is real alchemy taking place. Sexual attraction and falling in love are experiences enriched with emotions automatically triggered by a cascade of hormones. These are present in the very first social exchanges between babies and mothers but continue to fuel the passion of social intimacy throughout our lives. When this happens, we feel bewitched, enchanted, under a spell, charmed, and generally not in control. Something strange takes hold of us, and rational thinking seems to fly out the window. Breaking down human attraction into chemical neurotransmitters and sensory stimulus patterns may be how science describes the experience, but when Frank Sinatra sang about that old black magic called love, he was describing the supersense that there are mysterious forces at work when people fall in love.

THE RHYTHM OF LIFE

Chemicals and appearance are just two ingredients in the mix of social connectedness. Timing is everything for social relationships too. When two people don’t get on, they often say that they just didn’t click. We are rhythmic creatures who move in patterns and feel most comfortable with those who move in synchrony with ourselves. Just watch how lovers flirt during a courtship. They exchange glances, utterances, and caresses. If the timing is not right, the relationship is usually doomed.

Movement is also a fundamental way to identify whether something is alive or not. For example, aspects of movement tell us when we are dealing with an animal or an object. Objects move in a rigid fashion, whereas animals have a fluid, groovy motion. The next time you are in a shopping mall, watch how other people move. Smoothly and fluidly, shoppers steer and glide past each other to avoid collisions. Machines couldn’t negotiate a busy street full of people. Second, the type of movement is instantly obvious. If you attach luminous reflectors to a person’s forehead, elbows, wrists, knees, and ankles, then turn the room lights off, you see nine separate glowing spots in the dark. However, as soon as that person moves, you immediately see him or her as a person.13 Stop and the person becomes nine stationary points again. That’s because our brains are exquisitely tuned in to the smooth movements of living things even when we can’t see their bodies. It’s so fundamental that when shown these light point displays, even babies as young as four months see the invisible person.14

Like faces, sometimes movement can fool us into thinking that something has a mind. For example, toys that seem to come alive fascinate children. In my day, one of the popular toys was a piece of finely coiled wire called a “Slinky.” It could appear to walk by stretching and lifting up one end over another down an incline, a bit like an acrobatic caterpillar. The attraction of the Slinky on Christmas Day was the lifelike movement it had as it stepped down the stairs before someone trod on it or twisted the spring and ruined it for good. Toys that appear to be alive are curiosities because they challenge how we think inanimate objects and living things should behave. Many toys today exploit this principle to great effect, but be warned: not all babies enjoy objects that suddenly seem lifelike. This anxiety probably reflects their confusion over the question, “Is it alive or what?”

Once babies decide that something is alive, they are also inclined to see its movements as purposeful. They are beginning to infer a mind controlling the movements. In one study, twelve-month-olds faced a stuffed toy on a pedestal.15 It looked like a kind of furry brown Russian hat known as a “shapka,” with two button eyes for a face. Hardly the most convincing example of a living creature. However, unbeknownst to the baby, the shapka was remotely controlled by scientists hidden in another room. The baby watched the shapka. The shapka watched the baby. It was like the standoff in a spaghetti western. After a short uncomfortable silence, the hat suddenly beeped and moved. The baby was surprised and looked toward its mother for some explanation. None was offered. The baby pointed at the shapka and vocalized. The hat responded back with beeping. The scientists controlling the shapka made sure that it responded to every utterance and movement the infant made. Very soon the baby and hat were engaged in a meaningless but richly synchronized social exchange. When the hat swung around as if to look off to the side, the baby followed suit to see where the shapka was looking. The baby was treating the hat as if it had purpose. Simply by interacting in a synchronized way with the baby’s own responses, the shapka and baby had become the best of buddies.

Babies respond to such exchanges as if the objects are alive and have purpose. They infer intentions. However, if the shapka had simply moved randomly and had not had a face, this social connection would not have been made, and the babies would not have copied or tried to follow the hat’s lead. So movement and faces lead to the inference of intentional purpose. It’s such a powerful combination that it is almost impossible to ignore.

HERE’S LOOKING AT YOU, KID

Humans are natural people watchers, and most of the time we look at faces and eyes. The focus of another person’s gaze is a very powerful signal for us to look in the same direction. Magic Johnson was a great basketball player because he used the “no look” pass: he could pass the ball to a teammate without taking his eye off his opponent.16 He could control his gaze to hold the other player’s attention and not betray with his eyes where he was about to pass. More impressive was his ability to look toward one teammate and then pass to a completely different person, sending the defender on the opposite team in the wrong direction.

Our difficulty in ignoring the gaze of another person shows what an important component of human social interaction it is.17 They say that the eyes are a window to the soul. I don’t know about souls, but eyes are a pretty good indicator of what someone may be thinking. You can observe this yourself the next time you are standing in line at the supermarket checkout. Just watch the rich exchange of glances between people. It’s remarkable that we are often so unaware of how important the language of the eyes is. This is one reason why it is so unnerving to have a conversation with someone who is wearing sunglasses and we cannot monitor where they are looking. Police officers wear mirrored sunglasses to intimidate suspects for this very reason.

This sensitivity and need to see another’s eyes is present from birth. Newborn babies prefer that we look them in the eye. Even though their vision is so poor that they would qualify for disability insurance,18 they can still make out the eyes on a face, and they prefer the faces of adults whose gaze is directed toward them.19 Since they have little experience of people-watching, this strongly suggests that gaze-watching is another process built in at birth. People in love stare at each other, and parents and babies spend long periods engaged in mutual staring. If you look into the eyes of a three-month-old, the baby will smile back at you. Look away and the smiling stops. Look back and the baby smiles again. Mutual gaze turns the social smiling on and off.20 Not surprisingly, it works in the other direction. If the baby stares, parents smile. They really do have us wrapped around their little fingers.

Gaze is part of a general range of social skills called joint attention.21 When humans interact socially, they do so by sharing the same focus of interest. Whether it is discussing a topic, watching a basketball game, or admiring a painting, we can join in a combined effort to examine the world. Joint attention is not uniquely human; many animals use it to extend their range of potential interests or threats. Like meerkats, who watch each other for the first sign of danger, animals can gain the benefit of watching others watching the world. However, the jury is still out about whether other animals can infer the mental states that humans appear to infer.22 Consider this passage from Barbara Smuts’s “What Are Friends For?”:

Alex stared at Thalia until she turned and almost caught him looking at her. He glanced away immediately, and then she stared at him until his head began to turn toward her. She suddenly became engrossed in grooming her toes. But as soon as Alex looked away, her gaze returned to him. They went on like this for more than fifteen minutes, always with split second timing. Finally, Alex managed to catch Thalia looking at him.23

Smuts suggests that Alex and Thalia could be two novices at a singles bar. In fact, this description comes from her field notes of two East African baboons beginning a courtship. It could have been lifted straight out of a scene from Sex in the City, although I would guess that a woman suddenly grooming her toes in public might be considered a bit of a turn-off in downtown Manhattan. Are animals capable of mind-reading? Certainly they seem to follow gaze, but it is not clear that they can really get to the next stage, which is to think that others have mental states such as beliefs and desires. That is something that seems to be a particulary human quality, and one that infants achieve somewhere between their first year and second year.

THE GOOD SAMARITAN

Being able to understand others as having goals is a powerful mind-reading tool. It allows us to interpret other people’s actions as being purposeful and also allows us to anticipate what they might do next. Consider the following sequence of events as if watching a silent movie. Our intrepid climber approaches the steep hill and begins his ascent of the slope. Halfway up the hill, the climber comes to a level where he stops momentarily before resuming his journey. On top of the hill, another person is waiting. Suddenly this other person charges down the hill, blocking our climber’s progress and forcing him down the remaining slope with repeated shoving. What’s going on here? Is this about a land dispute? Or maybe they are dueling for the hand of the maiden who dwells at the top of the hill? What most people assume is that there is a clash of interest and that the two are not friends. In another version of the movie, instead of hindering our climber’s ascent, another individual comes along and helps the climber up the slope. Again, a fertile imagination could construct a feasible explanation. Is he a Good Samaritan who helps climbers up the hill?

Actually, the two events are computer animations used by Yale psychologists to investigate the origins of human morality.24 The various players in these mini-dramas—the climber, his assailant, and the Good Samaritan—are in fact geometric shapes with eyes simply moving around a computer screen. But when you watch these sequences, you cannot help but see them as purposeful individuals with goals and personality. At work here is the anthropomorphism that we described in the last chapter. Even simple geometric shapes seem alive if they move by themselves, taking paths that seem purposeful. Our anthropomorphism endows the shapes with humanlike qualities of mental states. By hijacking the rules for the movements of living things and applying them to objects, we effectively make them come alive.

Just like you or me, the twelve-month-old babies watching these sequences also judge the nature of each shape as good or bad based on the way it behaves. Long before we have a chance to teach infants about good and bad people, infants are making these judgments by simply watching social interactions. First, the climber is seen as purposeful with the desire to reach the summit. The assailant who forces the climber back down the hill is nasty, whereas the one who helps the climber is nice. We know this because if the helper or hinderer suddenly changes behavior, babies notice the switch. Babies know something about the nature of the individual players. Not only that, but when later offered a replica toy of the helper or hinderer to play with, almost all babies choose the helper doll. Babies prefer to play with the Good Samaritan.25

If, after pushing the climber downhill, the hinderer is painted so that it now looks like the Good Samaritan, babies are not fooled by the change in outward appearances. They know that deep down it is still a nasty piece of work because they are surprised if it suddenly starts helping the climber again. Babies know that appearances may be deceptive and that being bad is a deep personality flaw. As the saying goes, “A leopard can’t change it spots.”

SECRET AGENTS

Whether it’s heroic geometric shapes, animated toys, or contingent Russian shapkas, mind design forces us to treat such things as if they have purpose and goals. Our natural tendency to assume that people’s behaviors are motivated by minds allows us to predict what they might do next. This is what Dan Dennett calls adopting “the intentional stance.” When we adopt the intentional stance, we detect others as agents. An agent here is not James Bond, but rather something that acts with purpose. We attribute beliefs and desires to agents, as well as some intelligence to achieve those goals.26 This could be an adaptive strategy to ensure that we are always on the lookout for potential prey and predators. By adopting the intentional stance, you are giving yourself the best chance in the arms race of existence to find food and avoid being eaten.

However, the trouble with assuming an intentional stance is that it can be wrongly triggered. Things that don’t have intentions but seem to—because they either look as if they are alive (movements and faces) or behave as if they are alive (respond contingently)—make us think they are agents. We are inclined to think that they are purposeful and have minds. There’s a company in Somerset where I live that makes a vacuum cleaner that has a face painted on the front called a “Henry.” Actually, it’s called the “Numatic HVR 200-22 Red Henry vacuum cleaner,” but people know it as “Henry” for short. From reading the customer reviews on the Amazon website, where you can buy the vacuum cleaner online, it seems to be a fine little sucker. What is surprising is the way people describe the vacuum cleaner. Henry is not referred to as a machine but rather as a “he,” “a loyal servant,” and so on. As one customer put it: “We’ve had our Henry for about 14 years. He cleans the house, the car and DIY dust without a complaint…and he’s always smiling. How many of your household appliances do you apologize to if you accidentley [sic] bang it on a corner as you go around?” Henry clearly triggers a very strong intentional stance in his owners.

FIG. 10: The “Henry” vacuum cleaner. © NUMATIC INTERNATIONAL LTD.

I don’t think anyone really believes that Henry is alive or has feelings. But the vacuum cleaner does illustrate how easy it is to adopt the intentional stance. This may not be such a bad thing. After all, when we are trying to understand and predict events in the world, adopting an intentional stance gives us a useful way of framing information and doing things. For example, let’s say my car breaks down one day. Confronted with this, I have to plan a course of action to fix the problem. What’s troubling her? Maybe she wants a service. The old girl needs a face-lift. Dennett gives another good example.27 Gardeners trick their flowers into budding by putting them in the hothouse so that they think it is spring. The intentional stance is just a comfortable way of talking about and interacting with the natural and artificial world. But as we saw in Piaget’s animism in children, this way of thinking emerges early and may support a supersense that there are secret agents operating throughout the world. It is supernatural because it represents the over-extension of the intentional stance from real agents with minds to objects that cannot have this kind of mental life. Certainly we slip into this supernatural way of thinking remarkably easily. We may laugh it off, but as the saying goes, there is no smoke without fire. It must have some influence on our reasoning, lurking there in the back of our minds. The very same processes that led us as babies to seek out potential agents in the world continue to fool us as adults into thinking that the world is populated with purposeful and willful inanimate objects.

GHOSTS IN THE MEAT MACHINE

Whether we are reading our own mind or inferring the mind of others, we are treating minds as separate from bodies. This idea that the mind exists separately from the body is known as “dualism.” In his book Descartes’ Baby, Paul Bloom heralds an impressive avalanche of work to argue that humans are born to be intuitive substance dualists.28 Substance dualism is the philosophical position that humans are made up of two different types of substances, a physical body and an immaterial soul. Our mind is part of this soul that inhabits our body. The separation of the body and mind—or the “mind-body problem,” as it is known—is one that keeps philosophers and neuroscientists awake at night. Let me explain why.

Each of us experiences our mental life as distinct from our body. We can see how our bodies change over the decades, but we feel that we remain the same person. For example, I think I am still the same man I was in my late teens. I sometimes still behave that way. Our knowledge, experiences, ambitions, priorities, and concerns may change over the years, but our sense of self is constant. This is one of the most frustrating aspects of aging. Old people do not feel they have aged; only their bodies have. And what’s worse is that Western society is increasingly ageist. We treat old people differently and patronize them. But old people feel they are generally no different from when they were young. When we look in the mirror, we can see how the ravages of time and gravity have taken their toll on our bodies, but we still feel we are the same self. We may even change our beliefs and opinions with time, realizing that some punk music was actually pretty awful, but we don’t experience a change in the person having those beliefs or opinions. That’s because we cannot step outside of our mind to see how it looks from a different perspective. We are our minds.

In addition to the cruel injustice of youthful minds being trapped inside aging bodies, our daily experience constantly tells us that our minds work independently and in advance of our bodies. Every waking moment, we make decisions that precede our actions. It seems that our bodies are controlled by our thoughts. We feel the authorship of action. We are the ones doing the doing. This is the experience of conscious free will. However, free will—the idea that we can make whatever choices we want, whenever we want—is most likely an illusion. The experience of free will is very real, but the reality of it is very doubtful.

Cognitive scientists (those who study the mechanisms of thinking) believe that we are in fact conscious automata running a complex set of rule-based equations in our heads. We are consciously aware of some of the outputs from these processes. These are our thoughts. We experience the mental processes of weighing up evidence, considering options, and anticipating possible outcomes, but the conclusion that our minds have a free will in making those decisions is not logical.

If you doubt this (and most readers will), then consider this. If we are free to make decisions, at what point are decisions made and who is making them? Who is weighing up the evidence? Where is the “me” inside my head considering the options and doing “eeny, meeny, miny, moe?” That would require someone inside our heads, or a ghost inside the machine. But how does the ghost in the machine make decisions? There would have to be someone inside the ghost’s head making the choices. So if there is only one ghost, how does it arrive at a decision? Does it look at all the alternatives and then flip a coin? If so, flipping a coin can hardly be free will.

THE NUMSKULLS

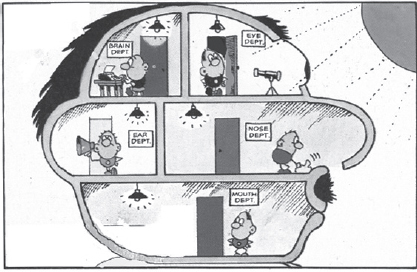

My editor tells me that these are really difficult concepts that need explaining, so rather than ghosts inside heads flipping coins, let me tell you about “The Numskulls.”

When I was a kid growing up in Dundee, Scotland, “The Numskulls” was the local comic strip about an army of little people who lived inside of the head of a man called Edd. They were workers controlling his body and brain. And like workers in a factory, sometimes they would screw up. For example, the Numskull controlling the stomach would see that reserves were getting low and send a request for more food. The Numskull responsible for feeding would pull the levers to get Edd eating. Maybe the Numskull in the tummy would fall asleep at his station because of all the food, and Edd would end up stuffing himself until he became sick. An alarm light would go off in the brain department, where the boss Numskull sat at his executive desk reading the incoming messages. Then there would be a frantic race to tell the eating Numskull to stop working. You can see how such a scenario easily generated comic story lines each week as the machine called Edd would encounter different problems arising from his internal workforce. It was one of my favorite comics, even though I did not realize that the creators were actually presenting children with a profound philosophical conundrum about free will.

FIG. 11: “The Numskulls” from my childhood. © D. C. THOMSON & CO., LTD.

The Numskulls show that decision-making is a deep problem. How are decisions arrived at? If a choice has to be made, how does that happen? We intuitively think that we make the decisions. We make up our minds. But how? Is there a Numskull boss inside my head? And if so, who is inside his head, and so on? Like an endless series of Russian dolls, one inside another, an infinite number of Numskulls becomes an absurd concept.

To cap it all, the experience of conscious decisions preceding events may also be an illusion. If I ask you to move your finger whenever you feel like it, you can sit there and then eventually decide to raise your digit. That’s what conscious free will feels like. But we know from measuring your brain activity while you’re sitting there waiting to decide that the point when you thought you had reached a decision to move your finger actually occurred after your brain had already begun to take action.29 In other words, the point in time when we think we have made a choice occurs after the event. It’s like putting the action cart before the conscious horse. The mental experience of conscious free will may simply justify what our brains have already decided to implement. In describing this type of after-the-fact decision-making, Steven Pinker says, “The conscious mind—the self or soul—is a spin doctor, not the commander-in-chief.”30 The mind is constructing a story that fits with decisions after they have been made.

As I write these heady sentences, I pause and pick up my coffee mug. This simple act is one of nature’s miracles. First, who made that decision if not me? More disturbingly, how can my mental thought cause my physical hand to move? How does mind interact with body? These are some of the most profound issues that have preoccupied thinkers for millennia, but most of us never even bother to consider how amazing these questions are. This is because we do not see a problem at all. We treat the mind and the body as separate because that is what we experience. I am controlling my body, but I am more than just my body. We sense that we exist independently of our bodies.

For most of us, it feels as if we spend our mental life somewhere resident behind our eyes, inside our heads. If we want to see what is behind us, we steer the ship around in order to look. If we want the coffee, we engage the coffee acquisition mechanisms. We feel like pilots controlling a complicated meat machine. There is only one Numskull in control inside my head, and it is I. But how can a nonphysical me control the physical body? How can a ghost inside my head pull the levers?

The dualist philosopher René Descartes proposed that the mental world must control the physical one through the pineal gland deep in the middle of the brain, which he called the seat of the soul.31 Descartes’ solution represents dualism, which requires that there be a soul that is separate from the body and yet in control of the body. But substance dualism must be wrong. The mind is not separate from the body but rather a product of that three-pound lump of gray porridge in our heads. When you damage, remove, stimulate, probe, deactivate, drug, or simply bash the brain, the mind is altered accordingly. In the last century, the great Canadian brain surgeon Wilder Penfield pioneered operations on awake patients for the treatment of epilepsy, including his own sister. He would expose the surface of the brain and then stimulate the region he was about to operate on to make sure that he was avoiding motor areas that might leave the patient paralyzed. When he stimulated the brain directly, the patients experienced movements, sensations, and vivid memories. They tasted tastes, smelled smells, and relived past experiences. Direct stimulation proved that mental life is a product of the physical brain.

Even if there were a seat of the soul that controls our body, how could we explain the relation between these two types of substance, the one immaterial and the other material? In other words, how could an immaterial substance act on a material one? It’s not clear how this could work. Descartes’ way of solving the mind-body problem, by suggesting a soul that controls the body through the pineal gland, crosses the boundaries between what we know about mental states (that they are immaterial) and what we know about physical states (that they are material). If something nonmaterial could act directly on something material, this would require a mechanism beyond our natural understanding. It would have to be supernatural.

And yet this is exactly what all of us experience on a daily basis. We don’t just believe that we are different from our bodies, but rather, as Bloom points out, that we occupy them, we possess them, we own them. Again, this is an illusion that the brain creates for us. For example, when you cut yourself, you feel the pain in your finger, but it is in fact in your brain. When you take a painkiller, it works by altering the chemistry of your brain, not your finger. And yet you feel pain in your finger. Patients unfortunate enough to lose a leg or an arm through amputation often experience their missing limb.32 Just like real limbs, these “phantom limbs” get itchy and can be tickled, but they too are an illusion. They are a product of a brain that has failed to update the loss of a body part in its overall map. As if some controller Numskull is looking at the schematic for the factory floor and has not realized that one section has been closed down. The brain areas previously responsible for receiving signals from the missing limb continue to fire away as if the limb were still connected. These examples prove something very disturbing. The brain creates both the mind and the body we experience. A physical thing creates the mental world we inhabit.

This experience of mind is personal and unavoidable. The Harvard psychologist Dan Wegner thinks that the experience of conscious free will in our minds may work like Damasio’s emotional somatic marker.33 Remember how emotions help us in our decision-making by giving us a sense of certainty? Wegner thinks that the experience of conscious free will works in a similar way. My body may tell me that it wants a slurp of coffee, but I experience the decision as my desire to have a drink. This enables me to keep track of my decisions by enriching them with a feeling of control. This is why we have the experience of purposeful decision-making and conscious appraisal. We need to take note of events for future reference. But we would be wrong in assuming that our mental experience at the time is responsible for the decisions we make.

Is all human mental life like this? What about plans for the future, such as schemes for revenge, humanitarian goals, and the need to crack jokes or write popular science books? In what sense could a conscious automaton be responsible for the whole gamut of mental life and aspirations that seems aimed at a future that has not yet happened? The fact that human activities and mental experiences are complicated is not under question. But in the same way we look at complex structures or behaviors in the animal world, such as building a spiderweb or constructing a wasp nest, and wonder how things so complicated could have evolved in creatures to which we don’t attribute minds, then we must equally entertain the possibility that humans are just more sophisticated life forms—forms that are capable of making plans and anticipating outcomes. The factors that feed into these processes that lead to complex mental lives in humans are diverse and multifaceted. The mental experiences that accompany such processing are undeniable, but we don’t need to evoke a mind that exists independent of and separate from the physical brain to explain them.

Even as a scientist aware of the problem of substance dualism and why Descartes’ solution is necessarily wrong, I still cannot ignore the overwhelming sense of my own mind as separate from my body and in control of my body, but ultimately I know it is a product of my body. How do the two interact? That’s the mind-body problem. That’s what keeps me awake at night. If all my daily conscious experience of a “me” residing in my head like a Numskull boss were actually true, then it would require a supernatural explanation to make sense of it. That’s because we have no natural explanation of how something that has no physical dimensions can produce changes in the physical world. This is why the mind-body problem is one of life’s great mysteries.

MIND MY BRAIN

The mind-body problem simply does not appear on most people’s radar. It is not a problem until someone points it out or you read books like this one. People have a vague notion that the mind and brain are somehow linked, but rarely do they stop to ponder how the two could actually talk to each other or how something nonphysical could interact with something physical. Most humans have experienced the consciousness of their own minds from an early age, even before they discovered they had a brain. Therefore, it’s not surprising that young children can tell you more about their mind than they can tell you about their brain.34 However, they rarely use the word “mind,” but rather use “me,” “my,” and “mine.” It’s a natural way to describe oneself. The brain, on the other hand, is something they have to learn about, and that comes with science education.

You can find out how much children learn about the brain by asking them a series of “Do you need your brain to…?” type questions. By the first year of school, most children, like adults, understand that brains are for thinking, knowing, being smart, and remembering. However, they still feel they have a mind in control of and separate from their brain. For example, they do not regard the brain as being responsible for feelings such as hunger, sleepiness, sadness, and fear. From the child’s viewpoint, “It is me who is sad, me who is tired, and me who is hungry.”

These responses tell us that children regard feelings as more personal than thoughts. This is because feelings affect us in a direct emotional way. When we are sad, we feel the pain, the misery, or the despair. It is “me” that suffers. When we are happy, we feel the elation, the excitement, or the contentment. Feelings are like an emotional barometer of change that we can compare from one moment to the next. It makes a lot more intuitive sense to say that I am a lot happier than I was yesterday than to say that my body and brain are producing different types of mood experiences from one day to the next.

More telling of children’s dualism is the way they consider the origin of actions. Actions are controlled by the mind. So kicking a ball or wiggling my toes is a decision made by me, not by my brain. These sorts of answers reveal that children are indeed intuitive dualists. When asked, “Can you have a mind without a brain?” all six- to seven-year-olds said yes. Science education does little to alter this belief: most fourteen- to fifteen-year-olds agree that the mind does not depend on the brain.

My hunch is that most adults also think the mind can exist without the brain. They may know the scientific position that the mind is a product of the brain, but as we saw with people’s understanding of natural selection, knowing the correct answer does not make it feel right. Adults who accept that the mind depends on the brain are likely to still make the same mistake as Descartes in thinking that the immaterial mind acts directly on the material brain.

ROBOCOP

When Officer Murphy was terminally wounded in the sci-fi film Robocop, he underwent radical reconstructive surgery to make him into a powerful cyborg.35 His brain survived, but his memories were wiped clean so that he could become Robocop. His colleagues treated Robocop as a machine, but his former partner, Officer Lewis, detected that there was still something of Murphy present. Over the course of the movie, the cyborg eventually regains traces of his memory to become Officer Murphy again. This tale of human identity is a familiar theme in fiction. A traveling salesman wakes up to find himself transformed into a giant verminous bug in Kafka’s The Metamorphosis, but he is still Gregor Samsa because he has Gregor Samsa’s mind. The replicant in the sci-fi modern classic Blade Runner is convinced that she is human because she has childhood memories, but the Tyrell Corporation, which created her, also fabricated her childhood.36 It would appear that the hallmark of human identity is a mind full of memories. Maybe that’s why most people say they would save a family album full of recorded memories from a burning house.

These examples suggest that we have some strong opinions about what makes something a unique human person, and they make for some interesting thought experiments.37 For example, imagine that Jim is involved in a terrible car crash and ends up in the hospital, where all the doctors can do is to offer a brain transplant. Consider these different scenarios. Jim’s brain is transplanted into a human donor’s body. Jim’s brain is transplanted into a donor body, but his memory is accidentally wiped clean during the operation. Or Jim’s brain is transplanted into a highly sophisticated cybernetic body. After the transplantation, Jim’s original body is destroyed. Which, if any, of these patients is still Jim?

Adults are more likely to say that Jim is still Jim if his memories are left intact, irrespective of whether his brain ends up in a human donor body or an artificial cybernetic one. Our conscious experience of our own minds and memories inclines us to think of minds being unique and the source of personal identity. We certainly don’t think our own minds and memories could belong to other people. So Jim is like Officer Murphy. He is the product of his mind and memories, and if these can be transplanted, even into an artificial body, he remains Jim. However, the patient with the brain but no memories is deemed to be more human than the cybernetic body containing Jim’s brain with memories. This pattern reveals that people consider humans in terms of a physical body and a unique mind that can exist separately.

What about minds existing independently of brains? Most laypeople think that the mind is separate from the brain. After all, the majority of humans have lived their lives never knowing that they possessed a brain, let alone knowing what it might be useful for. Also, as we will see later, people think that it might be possible to copy a body through some form of technology, and possibly even duplicate a brain, but they are less likely to think that a mind could be similarly copied. Moreover, if we could download the mind into another brain, most people assume that the identity associated with that brain would also change with the new mind. So we are naturally inclined to see minds as unique identities that can exist independently of the brain. If this distinction is drawn from an early age, it is easy to see how it leads us to the position that minds are not necessarily tethered to the physical brain. If this is so, then the mind is not subject to the same destiny as our physical bodies. Such reasoning allows us to entertain the possibility that the mind can outlive the body.

AFTERLIFE

In my experience, most Western parents don’t talk with their children about death unless they are comfortable with religious explanations. As someone who does not believe in an afterlife, I have found it very difficult to discuss death with my young daughters. It’s too painful and awkward. To begin with, you don’t have a happy ending, as you do with religion. Also, by discussing death, you are acknowledging that we are all destined to die one day. I will die, and my children will die. It’s the ultimate separation anxiety for both parent and child. This makes for a very uncomfortable reality check. All those oxytocin moments seem hollow, artificial, and ultimately pointless when faced with the prospect of death. I would imagine that most atheist parents like me probably avoid discussing death with their children to spare them the difficulty in coming to terms with an existence that has no purpose.

So young children are understandably confused by death. They do not know that all life comes to an end. They do not know that they are going to die one day. They do not appreciate that death is inevitable, universal, irreversible, and final.38 There are two main reasons for this. First, they cannot conceive of death because they lack a mature understanding of the biological cycle of life and death. As we saw earlier in discussing creationism, children conceive of life as always existing. Second, because of their intuitive dualism, they conceive of death in psychological terms, and in doing so, they can’t imagine themselves being dead. So death is understood as the continued existence of the individual, but somewhere else.

Most preschoolers think that death is like buying a one-way ticket to a new address with no prospect of return or home visits. When Grandpa has moved on, he has gone to another place. Even if the address is heaven, at least he still exists somewhere. Or they think that death is like sleeping. Certainly ideas of “departing,” “passing over,” and “resting in peace” are culturally acceptable to tell children and conceptually easier to grasp. No wonder the practice of burying someone in a box under the ground is a very disturbing notion for many preschoolers.

When kindergarten children were asked in a 2004 study about a mouse that had been killed and eaten by an alligator, they agreed that the brain was dead, but they thought the mind was still active.39 They understood that bodily functions like the need to eat and drink would stop, but most thought the mouse would still be frightened, feel hungry, and want to go home. Even adults who classified themselves as extinctivists—those who think the soul dies when the body does—said that a person killed in a car crash would know that he was dead.40 Our rampant dualism betrays our ability to understand that body and mind are tethered together in an inseparable union. When our body packs up, so should our mind. We cannot know we are dead.

Only as children start to learn about what makes something alive do they begin to understand the opposite process of what makes something dead. As we will see in the next chapter, a grounding in biology emerges late in development, and only then do children start to appreciate the mechanics of death.41 But understanding the mechanics and inevitability of death does not get rid of the belief in the immortal soul. Religion and secular supernaturalism encourage such beliefs, but we must recognize that the concept of the immortal soul originates in the normal reasoning processes of every child. For example, children raised in a secular environment may express fewer afterlife beliefs than children raised in a religious household, but they still retain notions of some form of mental life that survives death.42 We do not need to indoctrinate our children with such ideas for them to persist.43 It appeals to our supersense to think that we can continue to exist after our deaths.

WHAT NEXT?

Neuroscience tells us that the physical brain creates the mind. Our rich mental experiences, the sensations, perceptions, emotions, and thoughts that motivate us to do anything, are patterns and exchanges of chemical signals in the complex information-processing of a biological machine. But the mind has no real existence substantiated in the physical world. Psychology is the scientific study of the mind, but the mind does not exist in any material sense. Rather, the mind is the natural operating system that runs on the input and output of the brain’s activity. We can study its operations, but we would be wrong to think that the mind occupies a material existence independently of the brain.

However, that’s not what we experience when we consider ourselves. We are real, and we exist in the real world. When we think of “I,” we do so in terms of our mind. We experience our mind as an individual motivated by beliefs, desires, emotions, regrets about the past, concerns about the present, and plans for the future. We experience our mind as occupying the machine we call our body. We see our bodies as structures that can deteriorate but we rarely see the structure of our own minds. Even after mental illness, periods of delusion, or temporary intoxication, we usually explain changes in our mind as a result of “not being ourselves.” This is because we are our minds. The body does not create us. Rather, we are the one who controls it. The philosophical position of substance dualism is the natural way to experience our conscious mind as distinct and separate from our bodies.

Some consider mind-body dualism irrefutable evidence for why there must be supernatural powers operating in the world. The mind is seen as the causal agent, but for that to be true, the mental must be capable of controlling the physical. That would require supernatural powers, since such an arrangement would violate the ontological boundary between the mental and the physical. How else could nonmaterial minds control material bodies? However, most of us don’t recognize this position as dependent on the supernatural because minds controlling bodies is the intuitive default of our developing mind-reading of others, as well as our natural experience of our own minds.

The scientific position on substance dualism is that there is no separation of mind and body. It’s an illusion as false as the invisible square we saw earlier. Humans are conscious automata. Our bodies generate our minds. When our body dies, so does our mind. But the conscious automaton theory is both too unnatural and too repulsive to be accepted by most people. Furthermore, the impression that we have voluntary free will operating within our minds may also be an illusion. Free will requires someone or some ghost inside our heads making the decisions, and that simply gets us into an endless loop. Who is inside their head, and so on, and so on?

So the natural position, based on personal experience, is to assume a separate mind inside the body and not to worry about how the immaterial could control the material. Once we buy into the independent existence of mind and body, there is no limit to what the mind can do. If the mind is separate to the body, it is not constrained by the same laws that govern the physical world. It can leap great distances, travel through solid walls, never age, and travel forward and backward in time. In short, misconceiving the mind lays the foundation for many of the beliefs in both religious and secular supernaturalism. In the next chapter, we examine how misconceiving bodies also prepares the ground for our supersense.