CHAPTER SIX

Freak Accidents

ON DECEMBER 4, 1980, Stella Walsh, an innocent bystander, was accidentally caught in the crossfire of an attempted armed robbery at a discount store in Cleveland, Ohio. In her day, Stella had been the top athlete in women’s field and track events, setting twenty world records and winning both silver and gold medals for the 100-meter sprint in the 1932 and 1936 Olympics. Although resident in the United States, she represented her native Poland in the Games and was awarded that country’s highest civilian medal, the Cross of Merit. Everywhere she went, huge crowds turned out to celebrate her victories. In 1975 Stella was inducted into the U.S. Track and Field Hall of Fame. Five years later, a stray bullet in a parking lot ended the life of this once-famous sporting legend.

It was not Stella’s tragic death that was to cause a sensation, but rather the results of her autopsy. The sixty-nine-year-old former women’s athlete was not exactly who everyone thought she was. She was a he. Despite having been married and living life as a woman, Stella had male genitalia.

Initial reactions to the reports of this discovery led to outraged claims of sporting fraud and cheating. Stella was not a cheat because, technically, she was not entirely a man. She possessed both male and female chromosomes. Stella had a condition known as “mosaicism,” which makes an individual genetically both male and female. Her case was regarded as one of the reasons the International Olympic Committee decided to abandon gender determination tests prior to the 2000 Sydney Games. It’s just too difficult to distinguish between males and females, and genitals don’t maketh the man.

Mosaics such as Stella Walsh are rare, but it is not their rarity that fascinates us. It was not her sporting fame and untimely death that dominated the headlines at the time, but her being a “freak.” There are many rare and bizarre medical conditions, but only those that challenge our beliefs about what it means to be a human are called freaks. It’s a cruel term that we use to isolate those who do not fit our concepts of what it is to be a human.

During the Victorian era and early 1900s, freak shows were common. In what would now be regarded as politically incorrect entertainment, it was perfectly respectable to pay to see medical oddities. Conjoined twins, bearded ladies, microencephalics, dwarfs, giants, and albinos were all paraded as wonders of nature. Before the advent of modern medicine, many suffered gross disfigurement and physical abnormality through a variety of congenital disorders and progressive diseases, some of which are largely treatable today.

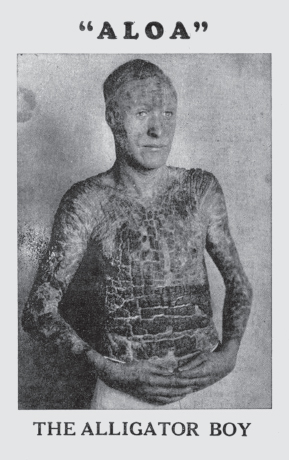

Famous freaks became celebrities, such as Joseph Merrick, “the Elephant Man,” who was a regular on the Victorian London social scene.1 Others, such as “Aloa, the Alligator Boy,” enjoyed minor fame trawling through the Dust Bowl towns of the U.S. Midwest during the Great Depression.2 Many of the acts were billed as part-human, part-animal monstrosities. They were abominations who crossed the boundaries between beast and man.

Although freak shows are now long gone, their publicity memorabilia and postcards are still highly collectible today. I keep a small collection as a poignant reminder of how the sensibilities of society have changed. While it may be no longer acceptable to gawk at physical abnormality, modern confessional TV reveals that we are still fascinated by the more deviant members of our society.

Human freaks challenge our view of the living world. We expect people to look a certain way and be a certain size and shape, and individuals who do not fit these expectations are deemed unnatural. When they have properties that violate our boundaries for grouping the world, they become freaks. For example, bearded ladies, hermaphrodites, and various transsexual combinations contradict our naive biological concepts about what it is to be a man or a woman. Our obsession with genitalia may be motivated by sexual interest, but they are also conspicuous markers for males and females. Whenever genitals are missing, diminished, shared, or on the wrong body, the individual’s identity is questionable. Likewise, those endowed with above-average sexual characteristics are judged to be more of a man or more of a woman. Size does matter in this judgment, rather than number. Those unfortunate enough to have multiple penises or vaginas and anything other than two nipples or breasts are generally regarded as freaks.3

FIG. 12: Aloa, the unfortunate “Alligator Boy.” AUTHOR’S IMAGE.

Where do we get our biological concepts? In this chapter, we are going to look at how the child constructs an understanding of the living world by applying the same intuitive theory-building we saw with minds and objects.4 Children begin by organizing the world and sorting it into categories. In trying to explain what they observe, they naturally assume that the living world is permeated by invisible life forces, energies, and patterns that define which categories things belong to. This is the stuff that animates matter and makes living things unique. Just like the intuitive theories of the mind that we saw in the last chapter, intuitive biological theories of life lead us to assume a number of ideas that lay the foundation for supernatural thinking.

Like the ancient Greek philosophers, children infer that living things have something special inside that makes them uniquely alive. They assume that there are essences5 that define what a living thing is, that there are vital life energies6 that cause things to be alive, and that everything is connected by forces. In philosophy these different but related notions are called “essentialism,” “vitalism,” and “holism.” As far as they go, they are pretty good approximations of what we know from science about life. If you open any modern biology textbook, you will find that such beliefs are in fact scientifically valid. For example, DNA is a biological mechanism for identity and uniqueness, which are core components of essentialism. Within all living cells there is a chemical reaction known as Krebs’s cycle that produces measurable quantities of energy.7 This is the vital life force that keeps the cell alive. Symbiosis is the study of the interconnectedness of biological systems. The connectedness of living systems can be found in evolutionary theory, in symbiotic physiology, and, more recently, in James Lovelock’s “Gaia” theory of ecology.8 No man—and for that matter no microbe—is an island; all must be understood as part of a complex system. Most of us are ignorant of these various discoveries and theories, but long before DNA, Krebs’s cycle, and symbiosis became mainstream science, humans naturally assumed their existence in the form of intuitive essentialism, vitalism, and holism. However, such intuitive reasoning also forms the core of the supersense because we infer essential, vital, and connected properties operating in the world that go beyond what has been scientifically proven.

Although we intuitively think of essences, life forces, and holism, we would be hard-pressed to describe what we mean. We can’t easily articulate these concepts because we often lack the appropriate terms or language. In Eastern cultures, such notions are recognized by ancient terms such as “chi” (Chinese), “ki” (Japanese), and “mana” (Polynesian). In Europe we used to have the term “élan vital” (life force), but this has been mostly abandoned. Having good or bad “vibes” is the closest that most of us come to phrasing these concepts. We may have lost our words to describe them, but our behavior and opinions reveal that essentialism, vitalism, and holism are still guiding our reasoning. When people respond negatively to wearing a killer’s cardigan, this is a reflection of their naive biological reasoning at work. The evil they think is imbued in the cloth is a reflection of the same mechanisms that children apply to infer the hidden properties of living things.

If such metaphysical beliefs are rarely discussed in the West and no one told us about them, then where did they come from? Once again, the most likely explanation can be found in the developing mind. They must come from our natural way of reasoning about life. In this way, children’s intuitive biology sows the seeds of adults’ supernaturalism, especially as our understanding about life influences much of our attitudes and beliefs.

KOSHER CATEGORIES

Jewish dietary law forbids the consumption of certain animals described in Leviticus of the Old Testament as unclean. At first, the lists seem rather arbitrary. Unclean animals include camels, ostriches, sharks, eels, chameleons, moles, and crocodiles. I have actually eaten three off this list without any ill effects. Some of the animals deemed fit for eating are even more unappetizing to modern tastes, such as gazelles, frogs, grasshoppers, and some locusts. On what basis did someone decide that sharks are unclean but most fish are acceptable? Sharks are fish after all.

Some people have suggested that avoiding certain taboo foods reduces the risk of infection. For example, there is a high risk of food poisoning from shellfish, which can spoil rapidly in hot climates. Undercooked pork can be a source of the parasitic infection trichinosis. However, such an explanation fails to account for many of the unclean animals.

One intriguing alternative is that originally the animals were deemed either clean or unclean depending on how well they fit properties of the group to which they belonged.9 In the case of mammals, it is clear that the clean or unclean judgment had something to do with how well each example fit general categories when it came to hooves and chewing the cud.

But this is what you shall not eat from among those that bring up their cud or that have split hooves; the camel, for it brings up its cud, but its hoof is not split—it is unclean to you; and the hyrax, for it brings up its cud, but its hoof is not split—it is unclean to you; and the hare, for it brings up its cud, but its hoof is not split—it is unclean to you; and the pig, for its hoof is split and its hoof is completely separated, yet it does not chew its cud—it is unclean to you. You shall not eat of their flesh nor shall you touch their carcass—they are unclean to you.

—LEVITICUS 11:4–8

Any group of animals should share more properties compared to those from another. Biologists call this grouping “taxonomy,” after the Greek taxis, which referred to the main divisions of the ancient army. Today’s modern taxonomy is based on one originally devised by the Swedish biologist Carl Linnaeus in the eighteenth century, but prior to this, taxonomies were based on animals’ different modes of movement and their habitats.

All the various animals of the land, sea, and air share very similar bodily structures and forms of locomotion. Land animals have four legs and jump or walk. Fish have scales and swim. Birds have wings and fly. One suggestion is that unclean animals tend to be those that violate these properties of the general category to which they belong. Sharks and eels live in the sea, but do not have scales. Ostriches are birds, but do not fly. Crocodiles have legs that look like hands. Maybe some of the unclean animals are the freaks of their taxonomic group. The early Jewish scholars thought that such violations were abominations of the natural world.

Our inclination to understand the world leads us to chop it up into all the different categories we think exist. By looking for the structure in the natural world, we group natural things together into their various kinds. In doing so, we acknowledge that members of a group share the majority of characteristics compared to members of a different group. However, in categorizing the natural world, we become aware that some members do not fit neatly into one category or another. Unclean animals and human freaks are violations of the natural order of things, and that order is one that we construct as part of the intuitive biology we develop as children.

IS IT A BIRD? IS IT A PLANE?

Give a twelve-month-old infant a bunch of toy birds and planes to play with. Then sit back and watch as something quite extraordinary happens. After the initial examination with eyes and then mouth, the baby will start to touch each of the birds in sequence, followed by touching each of the planes. Even though they may have similar shapes, with long bodies and stuck-out wings, the infant is treating birds and planes as different types of things.10 More remarkable is that six-month-olds shown different pictures of cats and dogs can tell the difference even though no two animals look alike.11 This simple demonstration reveals some very important things about babies. For a start, they are naturally inclined to sort out the world. They are thinking about things and forming categories. They must be thinking, This is one type of thing, whereas that is another. It’s exactly the sort of observational technique that professional scientists use when trying to understand the world. By sorting, they are telling us that they understand that dogs are members of one category whereas cats belong to another. In short, they have a rudimentary biology.

When and where does the child’s understanding of biology come from? The Harvard psychologist Susan Carey argues that children take a relatively long time to understand biology. They may be able to sort birds and planes and cats and dogs, but Carey thinks that such categorizing is only simple pattern detection that doesn’t require a deep understanding of biology. To get to grips with biology you have to appreciate life as a state of being, as well as the invisible processes associated with it. In Carey’s reckoning, it’s not until age six or seven that children begin to understand what it is to be alive.12

Also, babies may spot the difference between living and nonliving things, but they could just be making judgments based on how humanlike something is. In other words, they may be thinking nothing more than that the closer something in the natural world is to looking or behaving like a human, the more likely it is to have the same biological properties as humans. It’s anthropomorphism at work again, not reasoning about other life forms as separate categories. We can get an idea of children’s level of biological knowledge if we show them pictures of plants, insects, animals, and objects and ask them questions such as: Does it eat? Does it breathe? Does it sleep? Does it have babies? The closer things are to looking or behaving like humans, the more biological properties children give them. For example, in one study preschoolers thought that dogs and even mechanical monkeys were more likely to eat, breathe, sleep, and have babies in comparison to bees and buttercups because they resembled humans and seemed more purposeful than insects and plants.13

As far as it goes, this is not a bad strategy. It’s the preschoolers’ equivalent to the “if it looks like a duck, waddles like a duck, and quacks like a duck, then it’s probably a duck” approach to figuring out the living world. However, more recent research suggests that preschoolers do have something akin to a biological awareness that goes beyond simple outward appearances. Children think that there must be something inside animals that makes them both unique and alive. Before they reach school, children start to think like most adults in terms of essences and life forces. They are intuitive essentialists and vitalists.

THE ESSENCE OF LIFE

What is an essence? Consider the real essence of physical chemical compounds. Both flowers and cats can produce such a physical essence. In perfumery, essences are the concentrated reduced quantity of a fragrant substance after all the impurities have been removed. Chanel No. 5 is one of the world’s most successful perfumes and is very expensive because of the cost of harvesting one of its chief ingredients, jasmine blossoms. These are grown in the Provence region of France and survive for only the briefest time before losing their fragrance.

Another reason Chanel No. 5 is expensive, apart from jasmine essence, is that until recently it also contained musk secretions from the anal glands of the endangered civet cat, the same species in Asia that excretes coffee beans to produce the Kopi Luwak gourmet coffee mentioned earlier. (The civet cat is not actually a cat but a raccoonlike creature.) Musk is a sex chemical that a number of mammals use to attract partners and mark their territory. The pungent smell takes a long time to decay, and so perfumers use musk to prolong the scent of more fragile fragrances. When it became widely known that Chanel used civet cat musk in its perfumes, Chanel replaced this ingredient with a synthetic musk compound. It is not clear whether this decision was due to pressure from the animal rights groups concerned about the cruelty inflicted during the musk extraction process or, more likely, to consumers’ distaste at discovering that they had been smearing secretions from an animal’s buttock’s around their delicate wrists and necks.

In philosophy, essences are less smelly. In fact, you can’t detect them at all because they exist beyond man’s ability to perceive. Greek philosophers thought essences were some inner, invisible substance that made things what they truly were, like another dimension to reality. For example, Plato, probably the most prominent exponent of essentialism in his theory of ideal forms, argued that everything has an inner reality that we cannot necessarily perceive. Aware that appearances can be deceptive, he proposed that the world we experience is only a shadow of true reality. He likened human experience to sitting in a cave and watching reflections of reality from outside projected as shadows on the cave wall. It’s a bit like our Matrix comparison again. We glimpse only a fraction of the reality that truly exists. Plato thought that humans could never get at the true essence or form of things because of the limits of our minds.

Plato’s analogy is true in some sense—well, actually, all senses when it comes down to it. Our brains can process only the information we receive from the outside world through our senses. But our senses are limited. We know there is sound we cannot hear, light we cannot see, smell we cannot detect, and so on.14 This means that there are things in the world that we cannot directly perceive. There are microbes, viruses, particles, atoms, and all manner of teeny-weeny things that we know must exist but that are invisible to us. We are only ever glimpsing a portion of reality. Likewise, early essentialists thought that essences reside beyond our sensory range. Plato thought each essence is the core internal property that gives a thing its unique identity.

An essence is not to be confused with any unique property. For example, humans are the only mammals that have opposable thumbs. Thumbs may be unique to humans, but they are not essential. You would still be human if you were born without thumbs. Rather human essence is some invisible property that distinguishes us from nonhumans. Like the pod-people in the sci-fi classic Invasion of the Body Snatchers, alien replicants might be identical to us in every physical way, but they would lack the essential quality that makes us human.15

As comforting a notion as human essence might be—that even though our bodies wither and decay there is some enduring stuff inside us—this philosophical position is a logical non-starter. That’s because there is more than one way to define any object, including a human. The same individual human can simultaneously be a male, an adolescent, a prince, a neurotic, an artist, an athlete, an atheist, and so on. An object can be a stone, a paperweight, an ashtray, a weapon, a counterweight, or even a sculpture. And if there is more than one way to define an individual, you can’t have a unique essence of that individual. Aristotle was Plato’s student, but he realized that his teacher had been mistaken as far as essences were concerned. So the idea that there is only one true individual essence is nonsense.

When art critics and gallery owners talk about the essence of a piece of art, they are talking essential nonsense. However, just because something is nonsense doesn’t stop people believing in it. People can still hold a psychological essentialism.16 It helps us to think about uniqueness as a tangible property. This is my cup. This is my Picasso. This is my body. Psychological essentialism is the belief that some individual things, such as other people or works of art, are defined by a unique essence; as we will see in the coming chapters, such a belief would explain many of our attitudes when we think essences have been violated, manipulated, duplicated, exchanged, or generally mucked about with. Humans like to think that special things are unique by virtue of something deep and irreplaceable. When we chop nature up into all its different groups of living things, we are assuming that these are groups of things that are essentially different.

THE ESSENTIAL CHILD

Children’s essentialist thinking is amazing.17 Before they reach school age, they know that baby joeys raised by goats grow up into adult kangaroos, not adult goats. They know that apple seeds grown in flowerpots become apple trees, not flowers.18 They even know that a light-skinned baby switched at birth with a dark-skinned baby remains the original color despite being raised by the new family.19 A leaf insect may look more like a leaf than an insect, but four-year-olds know it shares properties with other bugs, not with leaves.20 When they are slightly older, they understand that if an evil scientist takes a raccoon and performs an operation to turn it into a skunk by attaching a furry tail, painting a white line down its back, and putting a bag of foul-smelling stuff between its legs, it is still a raccoon even though it looks like Pepé Le Pew.21 Essential thinking allows children to understand that the leopard literally can’t change its spots. And no one needs to teach children this. It’s part of their intuitive biological understanding.

Children’s essentialism is truly surprising, as preschoolers can often be fooled by outward appearances.22 However, once they understand what can and can’t be changed by environment, they are committed essentialists who see core properties everywhere. They think that there is something inside that cannot be changed. They don’t know what it is, and they would be hard-pressed to describe it. When it comes to understanding living things, they really seem to grasp that there is something deep inside that makes animals and plants what they are. It’s a universal belief shared by different cultures, suggesting that essentialism is a natural way of viewing the world.

Although children and most adults can’t describe exactly what an essence is, they can tell you where it is, if only indirectly. In one study, children were told about an ancient block of ice that had different animals frozen in it.23 Scientists wanted to determine what the different animals were by doing tests on small samples taken from the things inside the block. Children were asked whether it made a difference where the sample was taken from. By ten years of age, children reasoned like adults that it did not matter where the sample was taken because whatever defines an animal is spread throughout the body. In contrast, four-year-olds, the youngest children in the study, insisted that the true identity of an animal is found in only one spot and not spread out. When questioned further, these children seemed to think that the correct spot to choose was from the center of the body. What starts out as a very localized notion of essence in young children develops into a belief about something that spreads throughout the body, even though these children never mentioned scientific concepts such as DNA.

POLAR MICE AND FISHY POTATOES

Essential thinking is increasingly shaping our attitudes toward the modern world. For example, by the time the leaves on a potato plant start to wilt, the potatoes underground are already stunted in size as the plant tries to compensate for lack of water. What if the plant could tell you that it needs watering before the leaves begin to wilt? There is one such potato plant whose leaves start to glow fluorescent green when they require water. It can warn you in advance that it needs water before the underground potatoes shrivel. The plant can do this because a gene from a jellyfish has been inserted into its genetic makeup. It’s a genetically modified plant. When water levels reach the critical level, the gene in the plant’s physiology turns on the fluorescent response. A potato that can communicate its needs is truly remarkable—almost sociable. But would you eat such a fishy potato?24

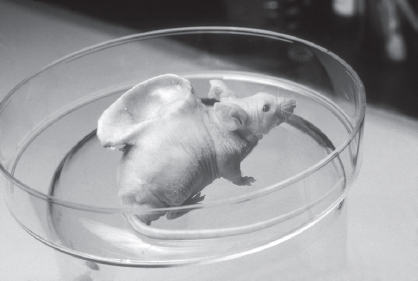

Or what about a supermouse that can survive freezing temperatures? The Alaskan flounder produces a protein that effectively produces an antifreeze in its blood to enable it to survive in subfreezing waters. Last year mice were bred with this gene that protected them from hypothermia.25 What’s more, the mice passed this gene on to their babies, demonstrating the potential to create new species of animals that cross the traditional taxonomic boundaries. In other words, these supermice were genetic freaks.

Those biological boundaries that we use to chop up the world are increasingly open to breech by new genetic engineering. There are real concerns about this technology, as it is not easy to predict exactly what unforeseen negative consequences may arise from artificially combining genetic material that would not normally occur in nature. In the remake of the sci-fi classic The Fly, the scientist Seth Brundle builds a machine that decomposes the body down into its constituent DNA particles and transports them from one pod to another where they are reassembled.26 By chance during one of his early experiments, a common housefly enters the pod with Seth. At first he notices nothing when he reemerges from the other pod, but over the course of the movie Seth is gradually transformed into a human fly hybrid, with all the disgusting dining habits that flies exhibit (and you know what I think about flies). In most people’s minds, genetic engineering has brought us to the point where Seth Brundle’s predicament is no longer a fanciful tale of the dangers of tinkering with nature.

It’s not the fact that we can do genetic manipulation that is so worrying. After all, from the very beginnings of farming and animal rearing, we have been manipulating genes through selected breeding. All modern dogs are descendants of a fifteen-thousand-year-old program of selective breeding of wolves.27 The problem is that gene insertion rapidly bypasses natural selection. There is no time to evaluate combinations that could be harmful. The potential for unforeseen consequences arising from unconstrained combinations worries the experts.

Around the world, governments are anxiously weighing up the concerns raised by genetic engineering with the potential benefits of new solutions to problems. For example, stem cells are the juvenile cells in fetuses that have the potential to replace damaged cells in adults.28 Many people suffering from illnesses and diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease would benefit if stem cells could achieve this repair. Unfortunately, there are not enough spare human eggs available to conduct this research, and so one solution has been to create animal eggs containing almost entirely human DNA. The resultant embryo, however, would still contain a small proportion of the donor animal’s original genetic material. This hybrid human-animal embryo could in principle be a potential real Seth Brundle. In truth, these embryos would never be viable, but the prospect of animal-human hybrids is simply too unacceptable for most of us. In March 2008, the British government faced a crisis as the Catholic Church urged Catholic politicians to resign over the introduction of the Human Fertilization and Embryology Bill, which allowed research inserting human DNA into animal cells. Ethics used to be a rather sleepy academic division of moral philosophy where one could ponder life’s hypotheticals. Today, advances in genetic engineering have thrust ethics into the public spotlight, with the expectation that it will provide answers to this minefield of moral dilemma. Philosophers have never been busier.

Your average member of the public has never taken courses in philosophy or genetics, but he can still be appalled by the prospect of combining species. This is because of essentialism. It’s the way we all chop up the living world into its different groups. We intuitively think that members of the same category share this invisible property that defines their group membership. For example, we think that all dogs have a “dogginess” essence that makes them members of the canine family and that all cats have a “cattiness” essence that separates them from dogs and makes them members of the feline fraternity. When we hear about scientists inserting genes of fish into mice and potatoes, we feel squeamish. It just does not seem right. It’s not natural.

FIG. 13: Mouse with an implanted bioframe. Many people have misinterpreted this image as an example of genetic engineering. © BRITISH BROADCASTING COMPANY.

Who did not feel the “yuck” factor when they first saw the picture of a hairless mouse with what looked like a human ear growing on its back, circulated around the world’s media? It wasn’t actually an example of gene manipulation but rather a demonstration of how an animal could be a surrogate host for growing an implanted bioframe.29 But it certainly looked like a hu-mouse! Our revulsion was not simply because it was a weird image. Rather, we felt simultaneously sick and fascinated because the prospect of human-animal hybrids violates the essentialist view of the world that we developed naturally as children. When I was preparing this chapter, my youngest daughter looked over my shoulder and saw the image of the mouse with the human ear. At first she let out an audible “yugh!” Then she asked if it could hear better. Apparently she is still telling her classmates about it.

MAY THE FORCE BE WITH YOU

Related to the notion of essence is the idea of a life force, something that is in living animals but not in dead ones. This is vitalism, an ancient belief that the body is motivated by an inner energy. Up until the nineteenth century, this was recognized in the West as the “élan vital,” a vital force that does not obey the known laws of physics and chemistry.30 In most conceptions of a life force, it is equated with the unique identity of the individual. In other words, it is the essential soul that many believe inhabits our bodies but departs on death to move on to another dimension/body/location/time (delete terms as appropriate depending on your afterlife belief system).

Although we cannot see the energy generated in our bodies, most of us intuitively feel it is there—not within every living cell, as Krebs’s cycle describes it, but rather as a unified whole thing that animates the body. I can relate to why people think this. On occasion, I have had to kill animals, either for food or because they have become a nuisance. I live in the country and raise my own chickens for the table. When they are ready, I pull their necks. When you kill a largish animal up close, as opposed to squashing a fly with a rolled-up newspaper, you can experience a sense that something leaves the body. A living entity that a moment ago was animated, flapping around and agitated, is now still. But there seems to be more involved than just an absence of movement.

I have seen a number of corpses in the dissection room, but I have not watched someone die in front of me. However, I have talked to friends and colleagues who have been at the bedside of a dying person, and they often report that something seems to depart. So far no one has told me that they actually saw something leave a body. Rather, they get a feeling that someone or something has left. Maybe this is what our minds create in order to makes sense of the change in the situation: suddenly there is one less person in the room. How can there be one person less in the room unless someone has left?

In popular culture, the moment of death is often depicted as a life force or energy leaving the body like some semitransparent copy of the person. This notion may be purely psychological, but there are many people who think a tangible soul exits the body at death.31 In 1907 Dr. Duncan Macdougall of Massachusetts reported that the soul weighs precisely twenty-one grams based on his careful measurement of six dying patients on a set of industrial scales.32 His findings were and have since been treated with much skepticism, with alternative explanations ranging from fraud to methodological weakness. Because the weight loss was not reliable or replicable, his findings were unscientific. When he was prevented from further human studies, Dr. Macdougall moved on to dogs that he sacrificed in his scientific search for the soul. The results of these studies showed no evidence of a weight loss at the time of death. Undeterred, Macdougall interpreted this as evidence for the Christian belief that animals don’t have souls. In which case the word “animal” is inappropriate, as it comes from the Latin anima, for soul.

Scientifically, death is another continuous stage of life. At death, the meat machine no longer functions as a unified system and begins to decompose. It starts to disassemble itself. In the absence of oxygen, the cells start to die. Krebs’s metabolic cycle shuts down, and the system starts to go into reverse. The bacteria colonies that once helped to sustain life now begin to break the body down. Like opportunistic looters, they requisition various material substances to embark on their own life cycles in isolate. It’s like the breakup of an army. Once the battle is over, the individual soldiers take what they can and then head off. The state of death is simply the process of life in different directions. With the defense systems down, all manner of microbe, insect, and beast plunder the body for resources. If we could record and play our lives out as one of those time-lapse movies of decaying fruits and animals, we would realize that composition and decomposition are continuous.

Such an account is neither comforting nor acceptable for most. Where has the person gone in this version? The body remains, but the person is absent. A departing life force that energized the body is the only sensible explanation for most people. The mind-body dualism we intuit when we are alive explains to us what happens when we are dead. And like dualism, the notion of a vital energy inhabiting the body is a concept that emerges early.

Young children understand life in terms of a vital energy necessary for keeping the body going.33 In one investigation, children were asked different biological questions, such as, “Why do we breathe?” To help them answer, the researchers offered the children three types of explanation: those based on mental goals (because we want to feel good), mechanical explanations (because the lungs take in oxygen and change it into useless carbon dioxide), or vitalistic explanations (because our chest takes vital power from the air). By six years of age, most children endorsed the vitalistic reasons, whereas older children and adults selected the mechanistic accounts. Education may have taught them about oxygen and carbon monoxide, but the explanation based on vital energy was the default position of younger children. Some children talked about blood carrying energy to the hands in order to make them move. Education provides us with new frameworks of explanation, but as we saw with naive theories of gravity and other intuitive models of the world, it’s not clear that earlier ways of thinking are abandoned. An enduring vital force seems a plausible explanation for life.

The concept of enduring life energy is not entirely flaky. A living body does generate energy in that it converts energy from one source into another. This is what metabolism is. Energy is never lost. This is the first law of thermodynamics, discovered over the last three hundred years. Energy cannot be lost but rather changes state. While very few of us are knowledgeable about the laws of thermodynamics, for many the transition from life to death is simply the movement of an energy source from one state to another. Many adults who are ignorant of the biological facts regarding metabolism and energy can nevertheless still conceive of some force that resides in a living thing but moves on at the point of death. We are intuitive vitalists.

But children do not start off as vitalists. The questions confuse them because they have not yet begun to think about their own bodies as separate from their minds. This may explain why they have a problem understanding death, as we saw in the last chapter. When five-year-old children were sorted into those who thought in terms of vital life forces and those who did not, the vitalist children were the ones who understood that death is irreversible, inevitable, and universal and applies only to living things.34 Younger, nonvitalist children were just confused. So an emerging naive vitalism helps children to appreciate the nature of death as final and something that happens to everyone. Intuitive theories don’t have to be scientifically accurate to be useful.

THE GREAT CHAIN OF BEING

The essential life force is not only an intuitive concept found in every child. It is also a belief that has survived thousands of years in different models of the human body, both religious and medical. The ancient Greeks described the essential life force in their humoral theory of how the body works. They believed that a healthy body depends on maintaining the balance of the four vital juices of blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile. However, as these bodily fluids are ultimately perishable, a fifth element, or “quintessence,” is necessary to animate the body with spirit.35 Today a similar idea is still the core component of traditional Eastern medicine and philosophy, whose treatments and rituals involve manipulating and channeling energy. The Greeks also recognized a holistic concept of life—the doctrine that unseen energies and forces connect everything in the universe. These connections are permanent, so that action on one thing in the universe has consequences further down the chain. The more closely things are connected, the stronger the consequence of action.

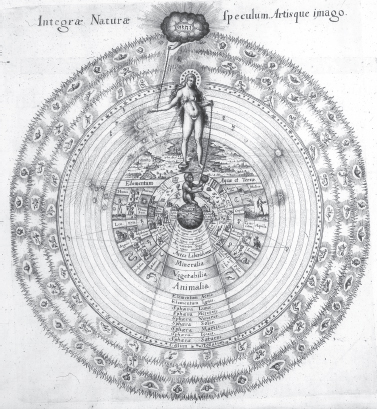

Such an idea underpinned the later dominant Western medieval theory of the universe known as God’s “Great Chain of Being.” This was the belief that all things, including animals, vegetables, and minerals, are related.36 All things originated from the same source, are organized into a hierarchy of association, and are held together by divine correspondences—invisible forces that connect the various elements. These forces could be sympathetic in that they shared common correspondences that could be combined. Or the forces could be antipathetic where the elements opposed each other and could be used to cancel each other out.

FIG. 14: Robert Fludd’s “Great Chain of Being.” PHOTOGRAPH BILL HEIDRICH. © UC BERKELEY

For example, in an illustration of God’s natural plan published in 1617, Robert Fludd’s diagram shows how man was sympathetically linked to the sun, which was linked to the grape vine, which was linked to the lion, which was linked to gold. Hence, men were noblemen. Gold was considered a noble metal, as was the name of the gold coin of this period. The vine was noble, and the mold that forms on overripe fruit and produces a characteristic rich flavor was known as the “noble rot.” The lion was a noble beast. Likewise, woman was sympathetically linked to the moon. Her menstrual cycle was clearly related to lunar activity, which was linked to wheat, which was linked to the eagle, which was linked to silver, and so on. Man was opposite to woman, and the sun was opposite to the moon. Everywhere in nature you could find evidence for sympathies and antipathies by looking for signatures of God’s hidden order. The evidence was overwhelming. You just had to look around you and see all the connections. This was trivially easy for a human mind designed to detect patterns and infer connections in the natural world.

Everywhere nature’s patterns were interpreted as reflecting a deeper causal model based on God’s hidden correspondences. Sometimes God left clues in that animals, vegetables, or minerals that shared sympathetic correspondences looked similar. This reasoning became known as the “Doctrine of Signatures” and was the basis for much alchemy and folk medicine.37 For example, because walnuts looked like the brain, they were used for headaches. The weeping willow tree was thought to be a cure for melancholy because of the clear signature of the drooping weariness of its branches. The foxglove plant (digitalis), with its spotted fingers, was originally thought to be a remedy for respiratory conditions because it was reminiscent of diseased lungs. Turmeric, the root commonly used to color Indian food yellow, was used to treat jaundice, a condition that produces a yellow skin pallor. Mandrake roots, which resembled shriveled humans, were considered to be particularly potent and, owing to their alkaloid toxins, could be used to induce altered states of consciousness for all manner of purposes. Nipplewort (lapsana communis), a tall weed with small yellow heads, was once esteemed for treating sore nipples. Pilewort (lesser celandine), with its knobbly tubers, speaks for itself.

Even today many societies value magical foods that are believed to contain essential healing or enhancing properties by virtue of their resemblance to body parts. Figs and pomegranates have properties that resemble female genitalia. The coco de mer coconut resembles a woman’s front bottom and is highly prized for fertility.38

Phallic-shaped foods like bananas and asparagus are also deemed to be potent by virtue of their resemblance to the penis. It’s not too surprising then that actual penises feature regularly as foods that can enhance male performance. The Guolizhuang in Beijing is China’s first restaurant that specializes in animal penises. Businessmen can pay up to $6,000 to eat tiger penis in the belief that it will improve their virility and life energy.39

FIG. 15: A coco de mer nut. What does it look like to you? AUTHOR’S IMAGE.

Much of traditional Chinese medicine is based on essentialist and vitalist notions of sympathies. Pregnant women are advised to eat dragon-tiger-phoenix soup, which combines the energies of snake, chicken, and our old friend the civet cat. Yes, that’s right. If it’s not enough that we drink its droppings in our coffee and smear its buttock juice on our necks, it’s also a popular ingredient in a common Chinese medicinal soup. Civets may have the last laugh against their human tormentors. The severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak that threatened a worldwide pandemic in 2003 was transferred to humans by civet cats stacked in crates in the infamous wet markets of the Far East before being shipped out to restaurants. SARS is a coronavirus. It replicates by hijacking the DNA contents of a cell and replacing it with its own genetic material. You could say that a coronavirus substitutes one essence for another. How ironic that the cherished supernatural essence of infected cats was in fact a real and deadly virile essence with a one-in-ten fatality rate.

HOMEOPATHY IS ESSENTIAL

Modern homeopathy is equally a direct descendant of sympathetic magical reasoning and logic. Much of its practice is based on the publication of the German physician Samuel Hahnemann’s (1755–1833) law of similars: similia, similibus curantur, or “like cures like.” If your baby has a diaper rash, homeopathy recommends treating it with poison ivy, a toxin that produces severe rashes. For children’s diarrhea, try a dose of rat poison. But don’t worry, the first law of similars was supplemented by the second law of infinitesimals, which states that the more dilute the dose the more effective the treatment.

Homeopathic remedies are diluted to such an extreme that it is unlikely that the liquid contains anything but pure water. This is because the practitioner adds the ingredient to a beaker of water and then takes one-hundredth of the solution and adds this to a new beaker. He or she then takes one-hundredth of that solution and repeats the process over and over again. A typical homeopathic remedy will be so dilute that it contains one particle of the original target ingredient in 1,000,000,000,000,000, 000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000, 000 particles of a liquid. You get the picture. You would have to drink twenty-five metric tons of water for there to be a remote chance that you had swallowed just one molecule of the original substance. Apparently this is not a problem. According to homeopathy, shaking the solution ten times with each dilution releases the vital energy of the active ingredient, which imprints a memory trace in the water.

Needless to say, the scientific community regards homeopathy as supernatural quackery. It is based on holist, vitalist, and essentialist beliefs. Yet it is an alternative approach to health that is increasingly popular. In 2007 the United Kingdom’s Times Higher Education Supplement reported a one-in-three increase in applications to study alternative medicine at alternative educational institutes and a corresponding decline in applications to study anatomy, physiology, and pathology at traditional universities.40 Homeopathy is available through the National Health Service, and even Bristol is home to one of five NHS homeopathic hospitals, despite the fact that the evidence for the efficacy of homeopathic treatments is at best equivocal. Boots, the United Kingdom’s largest chain of pharmacies, once rejected homeopathy but today sells a range of homeopathic remedies. It also includes a full online educational course to teach children about homeopathy, holistic healing, vital forces, and why diluted honey is good for bee stings.

What is it about modern medicine that leads people to prefer to put their faith and the care of their bodies into supernatural remedies? For one, homeopathy actually works. It works because patients believe it will. On average, one in three sick patients will improve if they believe they are receiving an effective treatment. This is the so-called placebo effect. The placebo effect is the remarkable finding that people get better if they think that they are taking a medicine or undergoing some therapy even if it has no direct active ingredient. Every drug that is regulated in the United Kingdom has to pass clinical trials that prove it is more effective than the results achieved by placebo alone. No such ruling exists for homeopathic treatments. For example, in the United States, Nicorette, a chewing gum that helps smokers give up smoking, had to pass stringent clinical evaluation before its maker gained a license to sell it. But in the same drugstore you can buy CigArrest, the homeopathic equivalent that did not have to pass any such evaluation. It would appear that the regulatory authorities are more concerned about the potential side effects of drugs with active components than treatments that are not distinguishable from pure water. Anyway, how could you prove that any homeopathic remedy did not have the appropriate active ingredient? You couldn’t find it if you looked for it!

The placebo effect is very real, and if belief improves health, then should we be concerned by supernaturalism in our health care? After all, homeopathic remedies are just water, and most practitioners refer to them as complementary medicine meant to be used in conjunction with clinically evaluated treatments. If this enhances the placebo effect, so be it. The problem occurs when complementary treatments are believed to be equally effective alternatives. This was revealed in a scandal made public last year about homeopathic anti-malarial treatments. The London School of Tropical Medicine was increasingly alarmed at travelers returning with malaria because they had not taken conventional prophylaxis. They found that of ten randomly selected homeopaths operating in London, all of them recommended taking homeopathic preventive treatments alone.41 This was despite the recommendation of the United Kingdom’s Society of Homeopaths, which concedes that there is no known effective homeopathic anti-malarial treatment.

There must be other reasons why people reject proven modern treatments in preference for supernatural cures. Over the past decades, there has been a change in attitudes toward modern medicine. For one thing, holistic treatments consider the whole of the person, and in doing so alternative therapists spend much more time listening to the patients and their problems in comparison to doctors working to a time-sensitive regime. Patient satisfaction and significant improvement in health are directly related to the amount of time the doctor listens to the patient’s problems.42 Not only is a problem shared a problem halved, but the sharing often leads to significant improvement in health.

Another reason for the rise in the popularity of alternative medicine is that we are increasingly concerned about the advances in science and treatments that seem unnatural. Have you noticed how common the word “natural” is in advertising today? In our so-called “postmodern” era, we hanker for a return to a simpler time, and a preference for natural products reflects this changing attitude and anxiety about modern science. But what exactly is a natural cure, and is it less dangerous than modern medical treatments? It turns out that nature has many more natural toxins than those synthesized by man. In fact, much of homeopathy works on the principle of a tiny bit of bad is good for you. So just because a substance is naturally occurring doesn’t make it safe.

DISGUSTING RESEARCHERS

The supernatural basis of alternative medicine sounds like the sort of mumbo-jumbo confined to the unenlightened dark ages of prescientific societies. But we should not be so quick to mock those who seek such treatments. The same laws of sympathetic magic are arguably part of daily life for all of us today, and no more so than in the peculiar human experience of disgust and our fears of contamination. Our contamination fears reflect our reluctance to come into physical contact with things that we find disgusting. We may be able to fight the urge and overcome our disgust, but it can operate at a gut level, making it difficult to control through reason.

Some things automatically trigger disgust and don’t have to be learned. Hydrogen sulphide, methane, cadaverine, and putrescine are four of the most revolting smells to the human nose. They can be found in various bodily excretions but are most concentrated in a decomposing corpse. When I trod on the stomach of that dead cat as a ten-year-old, it was this chemical cocktail that assaulted my senses. Everyone feels disgusted by the smell of putrefying bodies. However, other triggers of disgust are not so hardwired into our biology, and that is why disgust is so interesting to psychologists: sometimes it can be triggered by belief alone.

When we met Paul Rozin earlier, it was in the context of the killer’s cardigan, but this research stems from his work on the origins and development of human disgust. Rozin is one of the most disgusting researchers in the world. After reading about his studies, you would be very wary about stopping over for dinner at his place.43 For example, he measures how adults respond to various challenges that trigger the “yuck” response. Could you drink out of a glass after it has been touched with a sterilized cockroach? Could you eat a delicious piece of chocolate fudge shaped like a dog turd? Would you slurp your favorite soup after it had been stirred with a brand-new fly swatter? Why does spitting on your own food make it disgusting despite the fact that you need saliva for digestion? As you would expect, people are disgusted at the prospect of most of these challenges, even though the actual risk of contamination is minimal or nonexistent in each situation.

And then there are cultural variations. Many of us could quite happily tuck into a bacon sandwich (apparently one of the most difficult things for former meat-eaters to give up when they become vegetarian), whereas a devout Arab or Jew would consider it disgusting. In the West, we are appalled at the ease with which insects, penises, gall bladders, snakes, cats, dogs, and monkeys are consumed in the Far East. Clearly some forms of disgust are culturally determined. How can this be?

ESSENTIAL CONTAMINATION

Cultural variations prove that some triggers for disgust must be learned. When we watch others turning up their noses at particular foods or retching at certain sights, we can copy their responses. But disgust and the accompanying fear of contamination do not follow simple learning rules in the normal way. For a start, we are wired to respond automatically to others’ disgust. Simply watching someone pull a disgusted expression is sufficient to induce our own feelings of disgust. For example, if you watch somebody pull a face after sniffing a drink, this activates the insula, the same region of your brain that normally fires when you yourself smell something offensive.44 It’s one-trial learning. That’s how rapid and infectious disgust emotions can be.

For me, the really interesting aspect of disgust and the associated contamination fears is that they show all the hallmarks of supernatural thinking.45 This is because they trigger psychological essentialism, vitalistic reasoning, and sympathetic magic. For example, sympathetic magic states that an essence can be transferred on contact and that it continues to exert an influence after that contact has ceased. This is known as the “once in contact, always in contact” principle.46 Something you cherish can be ruined by coming into contact with a disgusting contaminant in exactly the same way. For example, the briefest touch of your food by someone you think is disgusting makes the dish unpalatable. There’s an old saying that a drop of oil can spoil a barrel of honey, but a drop of honey can’t ruin a barrel of oil. This is the negative bias that humans hold when it comes to contamination.47 We intuitively feel that the integrity of something good can be more easily spoiled by contact with something bad rather than the other way around.

However, it’s difficult to be reasonable about contamination once it’s occurred. It’s as if the contaminant has energy that can spread. For example, imagine that your favorite dessert is cherry pie and that you have the option of choosing between a very large slice and a much smaller piece. Unfortunately, your waiter accidentally touches the crust of the large slice with his dirty thumb. The same thumb that you just saw him pick his nose with. Which slice would you choose? Given the choice, most of us would opt for the smaller slice, even though we could cut off the crust where the waiter touched it and still end up with more pie. As far as we are concerned, the whole slice has been ruined—as well as our appetite.

THE WISDOM OF REPUGNANCE

Disgust affects more than just our attitudes toward the things we put in our mouths. It clouds our moral judgments too. Many people rely on disgust in deciding what they think is right or wrong. Leon Kass, the former chief ethical adviser to President George W. Bush, argued that disgust is a reliable barometer to what we should find morally unacceptable, the so-called knee-jerk response. In his essay “The Wisdom of Repugnance,” he makes the case that disgust reflects deep-seated notions and should be interpreted as evidence for the intrinsically harmful or evil nature of something.48 If you feel disgusted when you hear about some event, then that’s because it is wrong. The problem with this view is that what people find disgusting depends on whom you ask.

Consider incest between a consenting brother and sister. In most societies, brother and sister incest is regarded as disgusting. Why? What is wrong with two genetically related people having sex? We could argue that this response evolved because of the risks of inbreeding. For example, mating with your sibling is a genetic no-no, as there is an increased chance that any offspring would have genetic abnormalities. And yet if a brother and sister have consensual sexual intercourse in private so that no one would ever know, using birth control and basically avoiding any possible chance of pregnancy, we still consider such sex morally unacceptable. Then there are all the other weird things that people might get up to. Why is cleaning the toilet with the national flag or eating a chicken carcass you have just used for masturbation disgusting? These acts might be weird, but there is no intrinsic reason for why they are wrong.49 What’s wrong with wearing a killer’s cardigan? In fact, people are often lost for words when trying to give reasons. They are morally dumbfounded, as the psychologist Jonathan Haidt says.50 By the way, just in case you wondered about the warped state of my own mind, these disturbing examples all come from Haidt’s work. So write to him if they upset you.

Biological explanations are too limited for explaining all the things we find disgusting. Rather, the answer must be some other mechanism that uses disgust responses for some other purpose. One possibility is that disgust works as a mechanism for social cohesion. To form a cohesive group we must have sets of rules, beliefs, and practices that define our group and that each member must agree to abide by. This is how one gang distinguishes itself from another. These are the moral codes of conduct found throughout the different cultures of the world. When these rules are violated, a taboo has been broken, and a negative emotional response must be triggered. The perpetrator must feel guilt, and the rest of us must punish that person. This is how justice works. The net effect is to strengthen the cohesion of the group.

Culturally defined taboos may engender social cohesion, but they are not based on any reason other than that they define the group. This is why those individuals who are happy to touch a killer’s cardigan are outsiders. By taking a behavior and linking it to a visceral response, we can use disgust to control individual group members. We can also use disgust to ostracize others. In the next chapter, we examine how such essential thinking is at the root of bigotry directed toward people who some would rather keep at arm’s length because of their color or social background. When we say the peasants are revolting, we mean it in a disgusted way. It provides the emotional reason for treating them the way oppressors do. We can treat others badly who do not share our values because it feels right. And why does it feel right? I think the answer is that a supersense of invisible properties operating in the world makes these feelings seem reasonable, and disgust is the negative consequence of violating our sacred values.

WHAT NEXT?

In this chapter we have looked at an emerging biological understanding of the world that depends on categorization based on outward appearances and inferred invisible properties. Our mind design seems set to look for patterns and deeper causal explanations for the different kinds of things we think exist in the living world. This process leads to spontaneous untaught concepts of essences, life energies and holistic connection. Many of these beliefs can also be found in ancient models of the natural world where hidden structures and mechanisms where thought to reflect a supernatural order in the universe.

While these intuitive concepts have real scientific validity to some extent, our naive way of thinking about them leads us to attribute additional properties that would be supernatural if true. For example, supernaturalism forms the basis of belief for those who advocate the sympathetic power of diluted potions and magical foods that share some resemblance to the affliction under question. In these situations, belief alone is sometimes sufficient to produce the desired result even though there is no active ingredient in the potion or food. Like the illusion of control discussed in chapter 1, believing that you will benefit is sometimes good enough.

Such beliefs also influence the way we see ourselves as members of a group. In particular, our supersense leads us to infer something essential and integral to the group that should not be violated or contaminated by outside influences. When this happens, we feel revulsion and disgust. These are emotional states triggered by mechanisms that exhibit many supernatural properties of sympathies, antipathies and spiritual contamination. In this way, our supersense operates to unite the group members by shared sacred values.

Groups are held together by these sacred values. All humans can be disgusted and we would be very suspicious of anyone who did not experience this particular emotional response. When someone says that they could easily wear a killer’s cardigan, we identify them as an individual not prepared to share the group’s sacred values even when these values are purely arbitrary. This is because our supersense makes these values seem reasonable because of the moral indignation we experience fuelled by our intuitive emotional system. As social animals, we depend on our supersense, even when it flies in the face of reason.

In the next chapter we examine how this supersense can lead to some very bizarre beliefs and practices where we think we can absorb someone else’s essence.