CHAPTER EIGHT

Why Do Traveling Salesmen Sleep with Teddy Bears?

WHEN I LEARNED that SuperSense was to be published, one of the people I wanted to tell was Steve Bransgrove. Four years ago, I had wandered into Steve’s tiny shop on a cobbled street in the ancient nearby Somerset market town of Frome. Steve Vee Bransgrove Collectables was an Aladdin’s cave of memorabilia with items from bygone times such as postcards, tin toys, comics, medicine boxes, and all manner of common objects of no obvious worth. But people would pay good money for them, toys in particular. The objects were so evocative. If you closed your eyes, you could smell the decades pass you by. Literally, the shop had a wonderful aroma of the past, laced with the scent of Steve’s hand-rolled tobacco.

I remember the day I became addicted. I had casually flicked through some picture postcards in a box and discovered one of Tommy “Twinkle Toes” Jacobsen, the armless pianist. The publicity shot showed a jovial mustached man wearing a black tuxedo carefully balanced at a piano playing it with his bare feet! I was amazed that there was once a time when individuals like Twinkle Toes were considered celebrities. I bought the card, and that was the beginning of my brief collecting obsession. Over the next couple of years, I would visit Steve’s shop regularly. At first it was postcards from vaudeville and freak shows. Then for some reason I expanded into black-and-white postcards of beautiful 1930s movie starlets. Often on my visits to Steve’s shop I had no intention to buy, but we would chat about collecting and the people (mostly men in his experience) who follow this strange pastime. On each visit I invariably left with yet another small addition to my collection.

Steve had many wonderful tales of the obsessive collector—the wild look in the eyes, the change in expression when some coveted item was discovered, the agitated voice. He used to keep items under the counter for his regulars in the full knowledge that they would buy what he had to offer. Steve remembered each customer’s particular fetish. Like a drug pusher, he fully understood the power of the addiction, as both he and his wife Shirl were collectors too. Steve barely made a living out of the business, but he enjoyed it so much that I bet he would have worked for rent money alone.

Why do people do it? Collecting seems such an odd behavior in a world of instant upgrades, duplication, and modern innovation. Why look backward? When I entered the collector’s domain, I discovered a mirror world populated by legions of people who traipse around car trunk sales and flea markets every weekend seeking authenticity. Come rain or shine, these people were out in droves, looking for the original.

There is money to be made from collecting, but that’s not the only reason people do it. Money simply justifies the urge in most. The actor Tom Hanks, wealthy by anyone’s standards, collects pre–World War II typewriters. He sometimes spends more money repairing them than they are worth.1 Any collector can relate to this. For example, vintage cars are the folly of the extremely wealthy. It does not make financial sense to own such a collection.

Other people collect because of the joy of the pursuit of the missing piece. Such collectors are motivated to complete the whole set even if they cannot physically own the set. For example, in the United Kingdom we have people who collect train numbers. These individuals (mostly men) stand at the end of platforms of busy stations writing down the serial numbers of the different trains as they come and go. They are like bird-watchers, or “twitchers,” as they are known in the United Kingdom—the obsessed individuals (again usually men) who race up and down the country in an effort to spot as many different species of birds as they can find. This male passion for completing a set fits with Simon Baron-Cohen’s theory that we mentioned in chapter 5 about men being naturally inclined to order and systems.

However, collecting to completion is only one part of the obsession. Many collectors are motivated by the emotion generated by objects and the connection that objects make with the past. Collectors relish the sentimental feeling one can get from having and holding something from another time. If the object is associated with a significant person or event, the sense of connectedness is heightened. We recently conducted a large study of adults’ attitudes toward objects and found that, not only do we value authentic objects, but we also want to touch them.2 That’s why people will pay excessive amounts for Jackie Kennedy Onassis’s faux pearl necklace or bits of Princess Diana’s wedding dress. These authentic objects command distorted values in the mind of the collector.

Examples like these demonstrate that the urge to collect memorabilia can seem weird or strange, but Steve’s theory was that people collect memorabilia that reminds them of their own childhood or of better times when they thought they were happy. Objects are tangible, physical links with the past that can instantly transport us back to earlier days through a sense of connectedness. People don’t collect objects that make them feel sad. I am not sure what my motives were for accumulating postcards of sideshow freaks and Hollywood starlets, but I readily appreciated the pleasure in discovering a comic annual or toy in Steve’s shop that I had seen as a boy and the way it took me back over the years. Each object was like unexpectedly meeting a long-lost friend.

When I told him I was working on a book about child development and the origins of irrational behavior, Steve had promised to share tales of his more famous clients and their guilty collecting secrets. If I got a publisher, I would be back to discuss this more, as there are few things more irrational than the human obsession for collecting.

As I approached Steve’s shop to tell him the good news about the book deal, the first thing I noticed was that he was not standing in the doorway chatting to passersby with his trademark coffee mug and rolled-up cigarette. I then saw the note taped to the inside of the window. My heart sank. Had he gone out of business? Surely not, as I knew Steve ran the shop for the love of dealing in memories, not to make money.

FIG. 17: Steve Vee Bransgrove Collectables in Frome (2007), where I spent many a happy hour. AUTHOR’S IMAGE.

The truth was worse. Steve had died prematurely only weeks earlier in a sudden and rapid decline, before I even got a chance to know he was ill. In the letter taped to the window, his wife Shirl thanked everyone for all the words of kindness, but she could not continue the business without Steve and the shop would close. I returned only recently to see that the tiny premises were cleared out entirely, leaving just a shell, with the note still stuck to the window. I was surprised to see how large the shop had really been; Steve had packed it with so many objects that it had felt cozy and cluttered in a comforting way. It was like the guts had been ripped out of some big, friendly, furry animal. A bit like the man himself. I am sure such a sight would have broken Steve’s heart.

For me, the most poignant aspect of this story was not so much the loss of Steve (we all have to go) but the realization that many of us agonize and fret about possessions when we are alive. We accumulate objects over a lifetime in the belief that objects are important. We covet simple inanimate things. We invest emotion, effort, and time, and to what end or purpose? Only the very major collections survive intact, and they usually include recognized works of art with a commercial value. These are not the things that most of us could ever own. Personal possessions are often of little financial worth, and yet during our lives we are often annoyed or upset if they are damaged or lost. That’s because objects define who we think we are. We treat objects as an extension of ourselves. When someone dies, most of their possessions are distributed, sold, or handed down, but often they end up in the flea market or in the trash. It’s sobering to see how pointless a lifetime of collecting objects seems once the collector is gone. Sometimes when objects become symbols for a significant other, however, they can take on essential value.

Michel Levi-Leleu last saw his father Pierre in 1943 carrying a cardboard suitcase when he left the safety of a refuge in Avignon, France, looking for a new home for his Jewish family. Michel never saw his father again, but sixty years later the suitcase would reappear at the center of a legal battle over ownership.3

It was a terrible time when Michel’s father and suitcase went missing. The Jewish Holocaust of the Second World War was one of the most atrocious crimes against humanity in modern times. For the half-million annual visitors today, one of the most disturbing displays in the museum at Auschwitz is the pile of battered suitcases that once contained all the worldly possessions of families who would end their days in the death camp. Each case was labeled with the name of the owner in the belief that they would be reunited with their belongings again. The Nazis knew that to maintain the charade people had to think that their possessions were going to be kept safely and returned to them at some later date.

In 2005 Michel visited the Shoah Memorial Center in Paris, which was hosting a temporary Holocaust exhibit that included some of the suitcases on loan from Auschwitz. He knew his father had died during the war, but he could not believe his eyes when he spotted the suitcase with the handwritten label reading PIERRE LEVI. He asked for it to be returned. When the Auschwitz museum refused to hand over the suitcase, Michel took the museum to court. In court papers the museum stated, “The suitcases of prisoners deported to Auschwitz that are exhibited at the museum are among the most valuable objects that we have.” The Polish government backed the museum.

Museums thrive on displaying authentic items, but today many face legal battles for the return of items to the descendants or countries from which they were taken. For example, Britain has been locked in a diplomatic quarrel for some decades now to return the Elgin Marbles from the British Museum to Greece. In the United States, Native American tribes have demanded the return of sacred objects.4 Many museums now display copies and replicas without telling the public, or at least they give the impression that what you are viewing is authentic. This is because people want to make the connection with the original item. But like beauty, authenticity is often in the mind of the beholder.

Once again, this kind of reasoning is something I have experienced myself. The family expedition to the Niaux caves that I described in chapter 3 was not the first time I had visited a prehistoric cave. On a driving tour around France in 1990 I chanced upon the more famous prehistoric Lascaux caves in the Dordogne region.5 It was an unexpected opportunity, one not to be missed. At the time I was not particularly knowledgeable about or interested in prehistoric cave paintings and equally did not understand French particularly well, but I had heard of the Lascaux caves, and they were amazing. The animal drawings, all carefully lit in a remarkably accessible underground journey, were breathtaking. I was so naive that I did not realize my error. It was only when I left that I picked up a brochure explaining that the cave I had visited was in fact a reproduction of the original cave nearby that had been closed to the public since 1963 because of the problem of corrosive breath on the original paintings. I felt stupid and cheated. If I had known, I probably would not have bothered with the tour. Thankfully, the trip to the genuine Niaux cave fifteen years later, where we stumbled around in pitch-darkness, restored my sense of wonder in prehistoric art. No matter how good a reproduction is, knowing that it is not original destroys any sense of connectedness such an experience generates.

ESSENTIAL ART

In 2005 Sotheby’s in London sold Lady Seated at a Vestral for $32 million, following ten years of dispute about whether it was an original Vermeer masterpiece or a twentieth-century forgery attributed to the expert forger Han van Meegeren.6 After it was announced that the picture was an original Vermeer, its value soared. Nothing about the picture had changed—only the expert opinion about who had painted it. This proves that the appreciation of art is more than how something looks. It also depends on who you think created it. Auction houses typically charge up to 20 percent commission on sales, so it’s no surprise that the Vermeer authentication was provided by, of course, Sotheby’s own experts.

Provenance in collecting is the proof of originality. Collectors seek authentic originals with provenance because they are more valuable. But why are originals more valuable than an identical copy? One could argue that forgeries or identical copies reduce the value of originals because they compromise the market forces of supply and demand. In the same way that a prolific artist who floods the market with work undermines the value attributed to each piece, rarity means limited supply. For many collectors, however, possessing an original object fulfills a deeper need to connect with the previous owner or the person who made the item. I think that an art forgery is unacceptable because it does not generate the psychological essentialist view that something of the artist is literally in the work.

Such psychological essentialism has been taken to its logical conclusion in the world of contemporary art. This is especially true for the Young British Art movement of the 1990s. For example, one of the most notorious essentialist artworks is Tracy Emin’s piece My Bed, which was short-listed for the 1999 Turner Art Prize and sold to the collector Charles Saatchi for $300,000. The piece was simply the artist’s unmade bed surrounded by her soiled underwear, a vodka bottle, and crumpled cigarette packets taken from a time she spent several days in the bed owing to a suicidal depression. Other artists, such as living icons Gilbert & George, are equally notorious for works of art made from their bodily fluids and excrement. However, probably the most essential artwork is one that was regarded as a signature piece of the Young British Art movement.

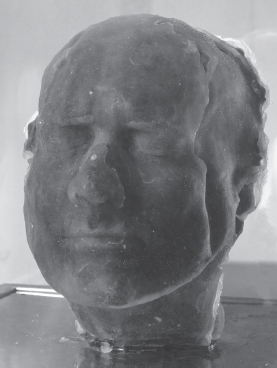

FIG. 18: Marc Quinn’s Self. © Marc Quinn. PHOTOGRAPH BY STEPHEN WHITE, COURTESY OF JAY JOPLING/WHITE CUBE GALLERY (LONDON)

Marc Quinn’s 1991 Self is a self-portrait sculpture of his head made from at least eight pints of the artist’s own frozen blood transfused over five months. Saatchi bought Self for $26,000. Interest in the piece was fueled by press reports in 2002 that workmen renovating Saatchi’s kitchen accidentally unplugged the freezer containing the head.7 However, Self was on display in the Saatchi gallery a year later, raising questions of authenticity. Because of the deteriorating nature of the material, Quinn re-makes the sculpture every five years with his own blood. Saatchi sold Self in 2005 to an American collector for $3 million. One wonders what will happen to this work of art once the source of original material runs dry. Will Quinn’s descendants be expected to replenish the supply of blood after the artist has died?

We all treasure sentimental objects from within our own lifetime that do not necessarily have an intrinsic worth other than their connection with a family member or a loved one. These objects are essentially irreplaceable. For example, engagement or wedding rings are typical sentimental items that are unique. If lost or stolen, most people would not regard an identical replacement ring as a satisfactory substitute, because these objects are imbued with an essential quality. Psychologically, we treat them as if there were some invisible property in them that makes them what they are.

But what if it were possible to make identical copies? Imagine that a machine existed that could duplicate matter down to the subatomic level, such that no scientific instrument could measure or tell the difference between the original object and the duplicate—like a photocopier for objects. If the object was one of sentimental value, would you willingly accept the second object as a suitable replacement? For most people, the answer is a simple no. Consider your wedding ring. Let’s assume that you are happily married and cherish the ring of gold on your finger. Would you accept an identical duplicate even though you could not tell the two apart? If you feel emotional, the answer is most likely not.

Identical replacements are not acceptable because psychologically we believe that individual objects cannot be replicated exactly even by a hypothetical perfect copying machine. This attitude is based on the assumption that originality is somehow encoded in the physical structure of matter. We intuitively sense that certain objects are unique because of their intangible essence. However, such a notion is supernatural. Let me explain why with a much bigger example: a whole ship.

THE SHIP OF THESEUS

Early in the hours of a Monday morning in May 2007, arsonists are believed to have set ablaze the nineteenth-century clipper the Cutty Sark, one of London’s major tourist attractions docked at Greenwich. Initial reports from the fire crews at the scene indicated that almost all of the ship had been destroyed. However, the ship was undergoing a $50 million restoration, and Chris Livett of the Cutty Sark Trust confirmed that half of the ship’s fabric had already been removed. He said that the ship had survived many potential disasters in the past and that the current crisis would be overcome.8 Even if the Cutty Sark can be restored, questions remain: Will it still be the original? When does restoration and repair become replacement? How much of the original can be replaced before it is no longer regarded as the same thing?

Whether at issue is a ship or a decaying work of art, such questions about restoration and conservation raise the philosophical problem of identity. If the material fabric of an object is replaced in its entirety, can the resulting object ever be said to be the original? What proportion of replacement is acceptable before the object ceases to be the original? What if the renovation is gradual?

Such issues raise interesting questions about how the mind represents objects in terms of originality after they have been repaired. The custodians of the Cutty Sark were quick to point out in early press releases hours after the fire that at least half the ship was already safely in storage. How did they come up with such a proportion so quickly? Was it based on weight or volume? I suspect it was based on the intuition that sudden damage to more than 50 percent of the ship would have been regarded as the catastrophic loss of the original.

This modern act of vandalism reminds us of Plutarch, the Greek historian who told of an ancient conservation project undertaken to preserve the ship belonging to the legendary Athenian king Theseus. Over the years the boat was kept in service by simply replacing the timbers that wore out or rotted with new planks, to the extent that it was unclear how much of the original ship remained. Plutarch asked whether this was still the same ship. What if the replaced planks had been kept and reassembled to form a second ship? Which ship, Plutarch asked, would be the original Ship of Theseus?

Psychologists have begun to look at these questions of authenticity and essential reasoning toward objects in the lab. For example, five- and seven-year-olds and adults were shown a picture of Sam’s “quiggle,” a nonsense object created for the purpose of the study.9 One group was told that it was an inanimate paperweight, and the other group was told that it was a type of weird pet. Participants were then told that Sam went away for a very long holiday and that while he was away various parts of the quiggle were gradually replaced. The participants were presented with a sequence of photographs showing how the quiggle changed each week. Finally, they were presented with two pictures: one of the quiggle that had been gradually transformed and now looked completely different from the first picture, and another of the quiggle made out of all the removed parts recombined to look like the original quiggle before Sam left. The question of interest was, after he returned from his journey, which was Sam’s quiggle?

Children and adults were more likely to say that the gradually transformed quiggle was the original, even though it looked very different and the reconstituted quiggle made of the replaced pieces was more similar to the picture of the original quiggle. This effect of continued identity over change was strongest when the quiggle was thought to be a type of living animal. This response fits with the intuitive biology of young children we discussed earlier. They understand that living things have something inside them that makes them what they are and that, despite outward appearances and changes, living things are essentially the same. This way of thinking is perfectly reasonable because we as individuals undergo significant change over our lifetimes as we age. Not only does our outward appearance change radically, but so do our insides. The body is continually replenishing its own structures and cells over the course of a lifetime, though few of us are aware of such biological details. For example, if you are in your middle age, most of your body is just ten years old or less.10 Now that’s a fact worth remembering when we consider our attitudes toward aging bodies!

However, for the older children and adults, even the quiggle that was described as a paperweight was regarded as the same object after undergoing radical transformation so that it no longer looked anything like the original. Younger children did not make this judgment. These findings show that with age we increasingly think of an object as being the same even though all of it is replaced with entirely new parts. In other words, there is something in addition to the physical structure of an object that makes it what it really is. What is this additional property? Where is it? It does not really exist, but we infer that it must be there. This is the essence that defines an object. As we grow older, we increasingly apply our developing intuitive essentialism to significant objects and living things in the world. I think this psychological essentialism is one of the main foundations of the universal supernatural belief that there is something more to reality. Where and when does this inclination to treat certain objects as special and irreplaceable first emerge? Remarkably, it may begin as early as in the crib.

SECURITY BLANKETS

I was listening to the radio this morning when I heard Fergie’s latest hit record, “Big Girls Don’t Cry.”11 In the chorus, she sings, “And I’m gonna miss you like a child misses their blanket.” Any parent who has raised a child attached to a blanket or teddy bear will readily know what Fergie is singing about and will be familiar with the intensity of emotion that such a loss can incur.

Estimates vary, but somewhere between half and three-quarters of children form an emotional bond to a specific soft toy or blanket during the second year of life. These items have various names, including security blankets, attachment toys, and transitional objects. They are “security blankets” because children need them for reassurance when frightened or lonely. They are “attachment items” because of the emotional connection the child forms with them. And they have been called “transitional objects” because one theory is that they enable the infant to make the transition from sleeping with the mother to sleeping alone. This may explain why such objects are more common in Western culture whereas they are relatively rare in societies such as Japan,12 where children continue to sleep with their mothers well into late childhood.

Although I was familiar with security blankets from the Linus character in the Peanuts comic strip, who is always seen carrying his blanket around with him, I did not fully appreciate the significance of such behavior until my first daughter developed an excessive attachment to her “Blankie,” a multicolored, fleecy blanket that was in her crib. Blankie went everywhere with her. If she became upset, she needed to have Blankie.

It can be disastrous when these items are accidentally lost. When I was talking about the items on radio phone-ins, I fielded calls from distraught parents who had suffered the consequences of their child losing their attachment object. It’s a fairly common tragedy, and as with lost pets, parents will post missing notices, such as the one shown here in the picture.

FIG. 19 A desperate wanted poster to return Laurel’s “Mouse,” lost in a Bristol park. IMAGE © KATY DONNELLY.

I contacted the mother of the little girl who posted this note in a local park. I was curious to discover whether her little girl’s mouse was ever found. She told me that it hadn’t been found, but remarkably, someone saw the plea and took the picture of the missing toy to their grandmother, who knitted a copy of “Mouse” using the same materials. Despite the kindness of strangers, little Laurel did not accept the replacement mouse. It did not have the essence of the original.

Around the time children begin school, most abandon their attachment objects. Still, many children grow into adults who keep their prized possession. When I began researching this phenomenon, I surveyed two hundred university students and found that three-quarters said that they had had a childhood attachment object, usually a stuffed toy or blanket. There was no difference between males and females in remembering that they had had such objects. However, most males had abandoned their attachment objects by around five years of age. In contrast, one in three female students still had their childhood object as an adult. These figures are based on a straw poll of memories from a select group of students and cannot be used to describe the general population. Most people are too embarrassed to admit that they still have their sentimental childhood objects. However, a recent survey of two thousand solitary travelers by a U.K. hotel chain revealed that one in five men slept with a teddy bear—more than the female travelers.13

Attachment to objects may be formed in childhood, but it’s a behavior that knows no age limit. Pamela Young is eighty-seven years old. On reading of my research into attachment objects, her son, Rabbi Roderick Young, got in contact to tell me about the most important possession in her life, a pillowcase from her childhood crib she calls “Billy.”

Pamela has had Billy for as long as she can remember. She sleeps every night with her head on Billy, clutching him with her right hand close to her face. Pamela has only ever been separated once from Billy—during an air raid in the London Blitz of 1944. She was staying in the Savoy Hotel with her first husband when the sirens sounded for guests to take refuge in the air raid shelters below. When she discovered that she had left Billy in her room, Pamela had to be physically restrained from returning to her room. Such is the power of sentimental objects. Roderick tells me that Pamela has requested that Billy be placed in the coffin with her, a promise Roderick intends to keep.

FIG. 20: Pamela Young with “Billy” in 2007. IMAGE © RODERICK YOUNG.

THE COPY BOX MACHINE

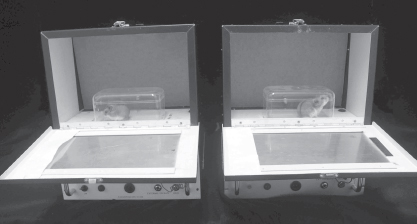

What is it about attachment objects that children cherish? Obviously, the physical properties are critically important for identification, but Paul Bloom and I suspected that the attachment ran much deeper than just the smell, sight, and feel of these objects. Why are they so irreplaceable? We decided to build the copy box machine to answer this question.

According to various physicists, duplicating machines are theoretically possible, just unbelievably improbable because they require vast amounts of energy and memory.14 Undaunted, we built a copying machine on a shoestring budget. It comprised two scientific-looking boxes with knobs and dials with flashing lights.15 Each box opened from the front so that an object could be placed inside. We showed this “machine” to four- to five-year-olds and demonstrated how it worked. We placed various toys in one box, activated the machine, stood back, and waited for several seconds. After a moment, the second box activated by itself to alert the operator that the copy had been made. It was amazing. When both boxes were opened, there was a toy in each that looked exactly the same. We copied various toys, making exact duplicates of the original. The children were convinced that the machine actually worked and did not figure out that there was a second hidden experimenter behind the machine feeding in duplicate objects. The critical test was whether or not children would allow us to copy their own toys. Of course, we could not really copy their objects because we did not have duplicate blankets and soft toys. They simply had to decide which box to open in order to retrieve an item.

We identified two groups of children: those with favorite toys but no particular attachment to them, according to their parents, and those children who needed to sleep with the object every night. Children with favorite toys thought the machine was “so cool” and happily offered their toys for duplication and even preferred to choose the box that was thought to contain the copy. In fact, they were often disappointed when we opened both boxes and confessed that the whole thing had been a trick. In contrast, the children with attachment objects either would not allow us to put their item in the machine in the first place or emphatically demanded return of the original. When we explained the setup, they were relieved to discover that their object could not be copied. Children did not want an identical copy of their attachment object. I think that they wanted the original back because a copy would lack the essential unique quality that we imbue sentimental objects with.

What about objects that did not belong to the child? Could we find evidence that they also thought others had unique possessions? Would they also treat the original and duplicates as essentially different? The copy machine was put into service again to look at the origins of authenticity and the value we put on memorabilia. We showed six- to seven-year-olds a metal spoon and a metal goblet and told them that one item was special because it was made of silver and the other was special because it once belonged to Queen Elizabeth II. This time it was easy to produce an identical copy, since we had bought two of each in advance. When we produced the second copy, we asked the children to value each item with counters. If the object had been described as special because it was made of silver, the children placed equal value on the original and the copy. It was made of the same stuff. However, if the item was said to have once belonged to the Queen, the same children valued the original over the copy. Something in the original could not be duplicated. Was it simply an association, or did children think that there was something of the previous owner in the object?

MISTER ROGERS’ CARDIGAN

The longest-running U.S. public television show was Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, which began airing in 1968 and had its final episode in 2001. It always began the same way: the congenial Fred Rogers returning home and singing his theme song, “Won’t You Be My Neighbor?” as he changed into his sneakers and a cardigan. It was a children’s show that dealt with the anxieties of growing up and coping with problems and expressing emotion, all delivered in a calm and serene formula that did not deviate over the decades. Fred Rogers, a real-life ordained Presbyterian minister, was a homely, placid, and comforting figure to the nation’s children. With almost one thousand episodes, Mister Rogers became a significant figure for millions of Americans. He received numerous awards and accolades and even had an asteroid, “26858 Misterrogers,” named after him. On receiving a lifetime achievement award at the 1997 Emmys, Mister Rogers brought the audience to tears with his simple and humble acceptance speech. On his death, the U.S. House of Representatives unanimously passed Resolution 111 honoring Mister Rogers for “his legendary service to the improvement of the lives of children, and his dedication to spreading kindness through example.” When his old car was stolen and he filed a police report, there was a public outrage. Apparently, the car was returned to the same spot with a note saying, “If we’d known it was yours, we’d never have taken it!” Whether this tale is true or not does not really matter. People would like to believe that it was true. The man was loved by generations.

The iconic symbol of Mister Rogers was his trademark cardigan. Over the course of his career, he actually wore twenty-four knitted by his mother. One of those cardigans is now on display at the Smithsonian Institution’s Museum of American History. Such is the reverence for Mister Rogers. No one could be more different from Fred West.

In a study of supernatural contagion, researchers wanted to know whether children would consider the cardigan of Mister Rogers a special garment imbued with his goodness.16 First they were shown two identical cardigans and told that one had belonged to Mister Rogers. They were then shown a picture of another child who did not know that one cardigan belonged to the famous man, and they were asked if wearing each cardigan would make the child look, feel, or behave differently. The youngest children, the four- to five-year-olds, did not think that wearing Mister Rogers’ cardigan would have any effect. Yet when asked the same questions, six- to eight-year-old children showed the beginnings of magical contagion by saying that the child would behave differently and feel more special. They also thought that something of Mister Rogers would pass from the cardigan.

The most remarkable result, however, was not from children but rather from twenty, mostly female, adult students. Most thought there would be an effect of wearing Mister Rogers’ cardigan in a child who did not know who it belonged to. Four out of five adults thought that the essence of Mister Rogers was in the garment, even though they themselves did not particularly want to wear it. This shows that there is a developing supersense when it comes to positive contamination that is a reverse of the Fred West cardigan effect. Both good and evil are perceived to be tangible essences that can be transmitted through items of clothing and contaminate them, and this belief strengthens as we grow older.

THE PRESTIGE

One of my favorite recent movies is The Prestige.17 It’s the story of two rival Victorian magicians who try to outperform each other with the ultimate stage illusion known as “the Transported Man.” Both perfect variations where the magician is apparently instantly transported from one wooden cabinet to another. “The prestige” is the illusory effect. The two men achieve this effect in different ways. One of them, Alfred Borden, uses the same principle of our copy box experiments and has his otherwise unknown identical brother appear at the second cabinet just at the right time so that it looks like the first brother has been instantly transported. The other magician, Rupert Angier, uses his wealth to recruit the brilliance of the mysterious and enigmatic Nikola Tesla, a real-life maverick genius of the time, to build him an actual copying machine that duplicates the magician at the second location.18 In the movie, Tesla achieves what our copy box only pretends to do.

Of course, it’s a work of fiction, but theoretical physicists have argued that it could be possible to teleport an object by decoding its physical information at one location and sending that information to reconfigure matter at the other end. This would create two versions of the object. Duplication is all very well and fine for inanimate objects, but what about copying real people? How would we cope with an identical copy of ourselves? In the movie, Rupert Angier solves the problem by drowning the original each time he duplicates himself. I think that this is an unlikely scenario. Not many people would willingly kill themselves so that an identical copy could live on the rest of their lives. Still, The Prestige raises really interesting questions about duplicated bodies and minds.

We cannot easily conceive of ourselves as being copied exactly. This stems from our increasing sense of dualism that I described in chapter 5. Physical states may be copied, but not mental ones. As children, we understand our own minds before we appreciate that others also have unique minds. With development, we become aware of our own minds as being unique and what makes us who we are. The possibility of exact duplication of our own minds is an affront to the sense of self. If we consider ourselves unique—and let’s face it, we all do—then the possibility that someone else shares exactly the same mind would mean that we no longer have our own unique identity. We would be exact clones. This is why having an identical twin who looks the same is a bit weird but ultimately not a problem. However, having a twin with exactly the same mind would be. We are happy to consider simple animals such as aphids as clones because we generally don’t attribute minds to insects. The difference arises with animals that we think may have minds. This is much more worrisome, and the reason human cloning is so repulsive to most.

We decided to investigate the origins of these intuitions with a live animal that we apparently instantly copied.19 We introduced six-years-olds to our pet hamster. We told the children three invisible physical things and three mental states about the hamster. We said that the hamster had a marble in his tummy, had a blue heart, and had a missing tooth. Note that we chose three properties that could not be directly seen. We did this because we wanted to compare invisible physical properties with three mental states, which are, by their very nature, invisible to others. We then induced three mental states of mind in the hamster. We asked the children to tickle the hamster, show it a picture they had drawn, and whisper their name in its ear. Each child understood that the hamster would remember each of these events. We then placed the hamster in the copy machine. When the second box activated, it was opened to reveal a second identical hamster. The question of interest was: which, if any, of the invisible states would the child think were present in the second animal?

FIG. 21: Then there were two. The copy box machine apparently duplicates a living hamster. AUTHOR’S IMAGE.

One-third of the children thought the second hamster was absolutely identical on all properties, and one-third thought it was completely different, sharing none of the same properties. The remaining children reported that while the invisible physical properties had copied (the missing tooth, the blue heart, and the marble in the tummy), the mental states had not. Children were beginning to draw a distinction between physical and mental properties and the possibility of duplication. Just to check, we repeated the study with a digital camera that recorded events such as hearing a name and seeing a picture. We also said that the camera contained blue batteries, had a marble inside, and had a broken catch. When we produced a second identical camera from the copying machine, all of the children thought that all properties had been readily duplicated. Likewise, if the original hamster was simply “transported” from one box to the other, children thought that everything remained intact. Duplication was the problem.

What do these findings tell us? First, children believe that the machine can copy objects faithfully but are less inclined to believe that this is true in the case of a living hamster. They draw a distinction between duplicates of inanimate objects and living animals. In particular, most children think that a copied animal would be different from the original. If anything is copied, it is more likely to be something physical rather than something mental. This suggests that children see living things as more unique than artifacts on the basis of nonphysical properties. This fits with the quiggle study I described earlier.

What if we had copied a real person? I bet that most of the children would not have regarded the copy as having the same mind. After all, would you? Paul and I are still considering whether we would ever be allowed to duplicate a child’s mother. Whether this study is ever conducted or not, we strongly predict that children would not readily accept a duplicated mother as a suitable replacement for the original any more than they would accept a copied attachment object. That’s because people are also seen as having a unique essential identity. Let me end with a warning about what happens when we lose our capacity to essentialize the world.

CAPGRAS SYNDROME AND THE ALIEN REPLICANTS

When I was a kid, I used to dismantle my toys to see how they worked. It’s something that many inquisitive kids do. The way something breaks down can give clues to how it works in the first place. Similarly, neuropsychologists are intrigued by how the mind works. They don’t go about dismantling minds, but they are very interested in broken minds. The way the mind disintegrates following damage or disease of the brain can be a really insightful way to gain an understanding of normal functioning. We know that damage to certain parts of the brain produces characteristic changes in the mind. It’s one of the reasons most psychologists are not dualists: they are very familiar with the idea that the mind is a product of the brain.

One of the more bizarre disorders that is relevant to thinking about the true identity of others is Capgras syndrome.20 This disorder is a delusional state in which the sufferer typically believes that family members have been abducted and replaced with identical replicants. Thankfully, the disorder is very rare; only a handful of cases have been reported in the literature. The delusion is associated with paranoia and can be very dangerous. Sufferers have been known to kill “imposters.” In one extreme case, a sufferer who thought his father had been replaced by a robot decapitated him, looking for the batteries and microfilm inside the head.21

Although the delusions usually involve significant family members, reportedly they have applied to family pets and personal inanimate objects as well. One patient thought that his poodle had been replaced with an identical dog.22 Another woman thought her clothes were replaced by items belonging to other people and would not wear them because she feared the objects would transmit an illness to her.23 When Capgras patients look in the mirror, they often don’t recognize themselves. One husband had to cover every reflective surface in the house because his wife suffered from Capgras syndrome and thought there was another woman out to replace her and steal her husband.24

I think that Capgras syndrome is what goes wrong when we lose our supersense that there are essences inside people, pets, and objects.25 It is more commonly associated with significant others because these are the individuals with whom we are most emotionally connected. One theory for the syndrome explains that our recognition systems for things work by linking the way something looks with an emotional tag.26 So you get a warm feeling when you look at your spouse, your pet dog, and maybe even your favorite car. When we look at significant others, we not only visibly recognize them but feel them as well. Like normal people, Capgras sufferers remember how they used to feel about such people and items, and they expect to get that same emotional signal.

The problem in Capgras syndrome is that this emotional tag is missing from the process, and so the sufferer is left with only the visible information. So the Capgras sufferer cannot feel that these are the same people, pets, and things that he or she used to experience before the illness. The only logical answer must be that these are not the same people, pets, or things. Rather, they must be identical copies. It’s the only way for the Capgras patient to make sense of the experience. This leads to the paranoid delusion that there is a conspiracy to replace things in the world.

Capgras syndrome is one specific illness out of a range of disorders in which patients believe things are not what they seem. These dissociated disorders reveal how important it is to have an essential perspective on the world. Without this essential sense of identity, people think that the world is a charade. It may look normal, but it lacks emotional depth. Those suffering from Fregoli’s syndrome, for instance, believe that someone else has taken on a different appearance. In the even more dissociated disorder known as Cotard’s syndrome, patients believe they must be dead because things are not what they used to feel. The world no longer seems real. Ironically, one reason why these syndromes are so rare is that brain injury to those areas that produce these disorders are usually fatal. Those who survive can have their experience of reality fundamentally distorted. The “something there” that William James talked about has gone. The supersense is part of this connectedness that we all experience, even though we are not fully aware of how it shapes the way we view the world. Without it, experience loses a vital dimension.

WHAT NEXT?

How can we best explain the emerging picture I have sketched here? As we discussed earlier, young children are essentialist in their reasoning about living things. They infer hidden energies and properties to living things from early on, even though they are not taught to think this way.

However, inanimate objects can also take on essential unique properties. In particular, the first sentimental objects may be the ones that help us through the early stages of separation and being left alone as infants. These attachment objects probably soothe children by offering some familiarity each time they are placed alone to sleep. However, over the next couple of years the child becomes emotionally attached to the object. What may have started off as a simple object soon becomes irreplaceable. In the case of attachment objects, it’s as if there is an additional invisible property that makes it unique.

Maybe this is where our sense of authenticity comes from, because around the same time children begin to appreciate that certain objects said to belong to significant others have an intrinsic value over and above their material worth. In our study it was the Queen’s cutlery and cups, but it could have been Dad’s watch or Mom’s clothing. I think that this makes sense from the psychological essentialism perspective. In the same way that children’s notions of contagion develop, their essentialist beliefs may also change from a localized focus of identity to one that spreads. Somewhere around six or seven years of age, children start to think that certain objects that were previously owned by significant others take on the properties of that person. This not only explains the origin of memorabilia collecting but also the emerging fear of coming into physical contact with killers’ cardigans or other conduits of evil. What’s more, this attitude may even intensify as we grow into adults and apply essential reasoning to others in the world.

The increasing tendency toward psychological essentialism may be a result of children developing a better understanding of what it is to be unique and an individual. Arguably, as we develop into adults, we have much more sophisticated ways of thinking about others as we form many more categories with which to pigeonhole people. Also, as we saw in chapter 5, children have an increasing sense of the importance of the mind as a unique property of the individual. This is why duplication of minds with a copying machine is so unacceptable. Our natural way of thinking about ourselves and other people leads to an increasing reliance on beliefs about identity, uniqueness, and things that can and cannot connect us.

So I would argue that the behavior of the toddler toward his grubby blanket and the obsession of a fanatical collector to own original memorabilia reflect the same human tendency to see objects as possessing invisible properties that originate from significant individuals. By owning objects and touching them, we can connect with others, and that gives us the sense of a distributed existence over time and with others. The net effect is that we become increasingly linked together by a sense of deeper hidden structures.

You may disagree with this theory. You might argue that not all of us form emotional attachments to objects or even collect. How could such a theory apply to the whole of humankind? I would reply that, like many aspects of human personality, such behaviors and beliefs probably exist on a continuum. Some of us are more inclined to this way of thinking than others, but we can all appreciate that there are hidden properties to the world. Like the supersense, we all vary in how far we are prepared to believe that there are additional dimensions to reality. And maybe these individual differences have something to do with the way our brains are wired as much as the different cultures we grow up in. Our supersense may have a biological basis, which I explain in the next chapter.