CHAPTER NINE

The Biology of Belief

SUPERNATURAL BELIEFS ARE not simply transmitted by what people tell us to think. Rather, I would argue that our brains have a mind design that leads us naturally to infer structures and patterns in the world and to make sense of it by generating intuitive theories. These intuitive theories create a supersense. I think this happens early in development even before culture can have its major influence. That effect of culture may occur much later in a child’s development. Meanwhile, there is something in our biology that leads us to belief. Yes, we can believe what others tell us, but we tend to believe what we think could be true in the first place. How can we prove such an account? The answer is to find a supernatural belief that most people hold but one that does not have its origins in culture. To do that we have to look behind us.

Have you ever felt the hairs standing up on the back of your neck, had the feeling that you were being watched, and turned around to find that someone was indeed staring at you? I don’t think there is a single person on this planet who has not had this experience. It’s so common that to not have had this experience would in itself be very strange. This sense of unseen gaze has kindled romances and saved lives. Lovers’ eyes have met across crowded rooms, and soldiers have turned around just in time to avoid the enemy sniper behind them.1 It is clearly an ability that has great adaptive value. If only it were true.

People report that they can detect someone looking at them even though there is no way that our natural senses could register this. We can’t see them, hear them, smell them, taste them, or feel the touch of their gaze, but people just seem to know when they are being watched. Around nine out of every ten people have this ability. Or at least they believe they do. Stop for one moment and consider how amazing such an ability would be if it were really true.

The sense of being stared at is an example of a common supersense that we have all experienced. In fact, it is so common that it leads to the belief that detecting unseen gaze is a normal human ability. Many educated adults who should know better do not even recognize that such a belief would be supernatural if true. This is why sensing unseen gaze is worth examining in detail as an example of a belief that emerges spontaneously over the course of development but then becomes accepted common wisdom. We don’t teach our children this common belief.

If we do not teach the belief of unseen gaze to children, where does it come from? To answer this, it is worth considering some related questions. How does vision actually work? How do we see objects in the world? Is there some energy that leaves the eyes when we gaze at something? The Greek philosopher Plato and the mathematician Euclid believed that vision involves such an “extramission” of energy from the eyes, a bit like Superman’s super-vision.2 Rays exit the eyes like a torch beam illuminating a darkened cave. Plato even talked about an essence exiting the eyes. However, we have known since at least the tenth century that vision works by light entering the eyes from the outside world as an “intromission,” not the other way around.3 Light can be reflected from our eyes, which explains the irritating “red eye” you get from flash photography and the spooky look of cats’ eyes caught in the car headlights.4 However, no modern vision scientist believes that there is energy originating and emanating from the eyes.

That’s why you can’t see anything when the room lights are turned off or the flashlight is broken. Somehow, such commonsense knowledge doesn’t seem to have affected our beliefs. We may understand that sunglasses protect our eyes from incoming harmful light, and yet we still intuitively think of vision working the other way around. Most people, including university students who have taken lessons in optics, believe that vision is the transfer of something entering the eyes at the same time as something exiting the eyes.5 This probably explains why the sense of being stared at seems so intuitively plausible. If there is something leaving the eyes, then maybe we can detect it. However, there is no current scientific framework that could explain such an ability. It is truly a supersense.

FASCINATING FORCES

“Fascination” means the enchanting power of another’s gaze that we find captivating. The psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud used the term in 1921 to describe the power of love, but he drew heavily on ideas from classical mythology and supernatural beliefs.6 For example, the Medusa was a female monster capable of turning men to stone by a look, and to this day many cultures still have beliefs in the malevolent power of “the evil eye.”7 This is the curse that someone can place on you simply by a look. Whenever he was addressing crowds and thought that someone might be giving him the evil eye, the Italian fascist dictator Benito Mussolini reputedly used to touch his testicles as a way of protecting himself. If you find this act a little embarrassing, or don’t possess a pair of testicles to touch, magical amulets are still available to protect against the evil eye in Mediterranean countries such as Turkey and Greece.8

The Italian Renaissance writers, such as Petrarch (1304–74) and Castiglione (1478–1529), described the look of love (innamoramento) as the transfer of particles from the lover’s eyes into the eyes of the beloved, which then work their way toward the heart.9 Here we have the combination of a naive theory of vision working with essences to explain fascination. Our language is peppered with such examples and metaphors that reveal how we treat gaze as something physical that exits the eyes. We talk about piercing eyes or exchanging glances as if there were some physical thing that passes between people.

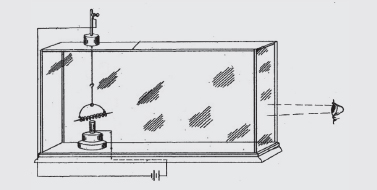

In the early days, some scientists believed that extramission was a measurable energy force that could be studied in the laboratory. In a paper published in The Lancet in 1921, Charles Russ wrote:

The fact that the direct gaze or vision of one person soon becomes intolerable to another person suggested to me that there might be a ray or radiation issuing from the human eye. If there is such a ray it may produce an uncomfortable effect on the other person’s retina or by collision with the other person’s ray; it is a fact that after a few seconds the vision of one or the other will have to be turned away at least for a short time. Numerous everyday observations and experiences seem to support the possibility of the existence of a ray or force emitted by the human eye, and in order to give my theory the support of some experimental evidence I decided to try and find or create some instrument which should be set in motion by nothing more than the impact of human vision.10

There are many things I find visually intolerable about other people that make me feel uncomfortable and in need of turning away, such as seeing someone pick his nose or clear his sinuses, but I would not make the mistake of assuming that just because another person affects me in a physical way, there is a physical energy field at work. Such logic did not dissuade Russ, who patented a box that contained a copper wire set across a magnetic field to measure this fascinating force.

FIG. 22: A reproduction of the patent for a machine to measure the energy of gaze emanating from the human eye filed by Dr. Charles Russ in 1919. AUTHOR’S IMAGE.

I could not find any evidence of replication of Russ’s findings, and so we must conclude that the rest of the scientific community abandoned this line of inquiry.

THE SENSE OF BEING STARED AT

In 1898 Edward Titchener reported in the prestigious journal Science that nine out of ten of his Harvard undergraduate psychology students believed they had the sense of being stared at.11 I repeated this survey with more than two hundred Bristol students one hundred years later.12 To my surprise, the same number of students agreed that it is possible for people to detect unseen gaze, even though these students had taken courses in vision and knew that vision is an intromission process. They should have known that such an ability is scientifically implausible, yet their intuitions told them otherwise. Nevertheless, just because we believe we can sense being stared at does not make it real.

For the record, there are studies that report significant evidence for the ability to detect unseen gaze. A typical way of measuring this is to have an observer stand behind a blindfolded participant, then either stare at the participant or keep his or her eyes closed. Some studies have even been conducted via a camera link, with the two individuals in separate rooms. (This would make Russ’s energy field explanation even more implausible.) The staring and not staring are alternated. Trials are repeated many times, and the number of correct guesses is compared to the statistical average of 50 percent that would be expected if we had no ability to detect when someone is staring at us. The largest study involved eighteen thousand trials with children, and it reported a highly significant effect.13 Something is definitely being detected here. Isn’t that proof enough of the ability?

In my opinion, one of the most interesting discoveries to emerge from these studies is not the ability to detect unseen gaze but rather the remarkable capacity of the brain to detect patterns. Studies that report a significant sense of being stared at have tended to use sequences that may not be truly random. What appears to be happening is that the blindfolded participant is learning to detect these nonrandom sequences.14 Remember the example in chapter 1 of pressing “1s” and “0s” on the keyboard? Humans are tuned to detect patterns of alternation, even when we are not consciously aware that we are doing so. We seem to be able to detect patterns of sequences if we are given feedback on every trial. If you don’t tell participants how they are getting on after each trial, the effect disappears again and performance returns to chance.15

Science cannot categorically prove that the sense of being stared at is not true or will never be true in the future, but the evidence is so weak or nonexistent that it must be regarded as unproven. There have been many failures to replicate the effect reliably, so as the saying goes, “One swallow doesn’t make a summer.” It is unscientific to keep flogging a dead horse if the effect you seek refuses to replicate reliably. Not only must scientists find evidence for their theories, but they must also abandon them when the evidence fails to stand up to scrutiny, especially if those theories would overthrow the conventional theories that up to that point have been so reliable. Why should a glimmer of some possible effect overturn a body of work that has undergone rigorous testing and validation? As the saying goes, “Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.”16 So where does this common belief in the ability to detect unseen gaze come from?

DEVELOPING A SENSE OF THE UNSEEN GAZE

I think the sense of being stared at is a supernatural belief, but one with a very natural origin that can be traced to a naive theory of how vision works. The sense develops into a full-fledged supernatural belief as we become more tuned in to the language of the eyes and our growing sense of connectedness as adults.

If you ask young children how seeing works, they respond that something leaves the eyes.17 For example, if you show them a picture of a balloon and a person and then ask children to draw “seeing,” they typically produce an arrow from the eyes to the balloon. Is this so surprising? After all, we look at things in the world. We are the source of the looking, so seeing must come from the observer. We look by moving our gaze around the world to see the different sights. We control where we look, and so the experience of vision is that it originates from within ourselves.18 Remember the Numskulls inside our heads guiding our body and controlling our eyes by moving them around to see? It is easy to understand why most of us think seeing works in this way from an early age.

Do such naive beliefs explain the sense of being stared at? Actually, the picture is much more interesting. If you ask children about whether they can sense being stared at, they generally report much lower levels than adults.19 I expect that’s because most young children are so self-centered that they are mostly oblivious to others around them. That’s something that changes as we become more self-conscious about being watched. So the sense of detecting unseen gaze actually increases as we get older! Why do more adults than children believe that they can detect unseen gaze? After all, adults should be more scientific and rational than children. I think the explanation involves our increasing social connectedness to others, our attention to their eyes, the developing mind-body dualism we discussed earlier, and the accumulation of evidence that confirms our intuitive beliefs.

THE EYES HAVE IT

Studies of child development reveal that we become much more sensitive to other people’s gaze as we get older.20 Gaze is such an important channel of communication that we automatically pay attention to it. In fact, we can’t ignore it. That’s why having a conversation with someone who repeatedly breaks fixation or glances off is so annoying: they are thwarting our attempts to read their thoughts based on their gaze. So gaze is crucially important to us.21 When someone stares at us, it directly stimulates the emotional centers deep inside our brain. Staring is not a passive act but an active event that affects us emotionally.

The amygdala and ventral striatum are the emotional structures deep within the brain that fire during social exchanges.22 They give us the feelings we experience during social interactions. Direct gaze at a distance is fine for recognizing people, but direct gaze close up can make us very uncomfortable.23 If it’s coming from a lover, direct gaze makes your heart pound and releases butterflies in your stomach. If it’s coming from a stranger, your mind races (What does he want with me?). That’s why no one stares at other people inside elevators. We prefer to look at the ceiling or the floor rather than at each other. We are too close for comfort.

Children, on the other hand, have to be told not to stare. As we saw earlier, babies look at eyes from the very beginning, but with age, we become more attuned to gaze. As we approach adulthood, we need to be able to figure out friend or foe, and so we increasingly learn the subtleties of social interaction and the meaning of a glance. We also become more self-conscious about the others around us, and our need for social approval intensifies. Anyone who has ever been to a party of adolescents cannot fail to notice the flurry of exchanged glances between the two sexes. These fledgling adults are embarking on the first stages of intimacy, and these early steps involve reading the language of the eyes.24

The emotional arousal we experience when we are being stared at simply reinforces our intuitive sense that we can detect another’s gaze as a transfer of energy (Why else would I feel this way when she stares at me?). Now put yourself in a situation where you suddenly feel uncomfortable with other people around. With this naive theory, we readily remember every occurrence when we sensed this discomfort that proved to be justified, but we conveniently forget every time when we were wrong. Like any theory, this one comes with a bias to seek out confirming evidence of what we think is true in the first place.

This tendency to look for confirming evidence is known as the confirmation bias. It’s the prejudiced reasoning we exercise whenever we make judgments that fit with our preconceptions. We rarely take things at face value but rather look for confirmation of what we believe to be true in the first place. This has been used to great comic effect by the American mortgage company Ameriquest, which has been running an ad campaign showing how easy it is to jump to unjustified conclusions when you don’t know all the facts and when you reason according to your preconceptions. My favorite is the father who is giving his daughter and her friends a lift when they stop off to buy some chewing gum. He calls her back briefly to the car to give her $20 to buy the gum. As she leans in through the window, he says, “Here’s some money.” At that moment, a police patrol car pulls up behind. “What have we got here?” says the officer as the older man is handing over money to the clearly underage girl. “I’m her daddy,” stutters the father caught in the headlights like a startled deer. The tagline is: “Don’t judge too quickly. We won’t.”

The confirmation bias reveals that preconceptions easily shape the way we interpret information. If you think that you can detect unseen gaze, then you remember every example that confirms your belief and conveniently forget all the times you were wrong.

Finally, a sense of being stared at can strengthen from the error of causal reasoning, post hoc, ergo propter hoc (after this, therefore because of this), described earlier as the basis for superstitious reasoning—in other words, assuming a cause where there is none. Imagine the situation. You are walking down the road and pass a group of youths. You get the uncomfortable feeling that they are staring at you. You stop and turn around and find out that you were right. But consider the sequence again from the perspective of one of the youths. You are hanging out with your friends and this guy walks past. You give him a glance but continue talking to your friends. Suddenly the guy stops and turns around. What do you do? You look back at him to see why he has turned around. In other words, walking down the road, we may think that we turn around because we sense others looking at us from behind but in reality, they look at us because we turned around to face them in the first place. We are so self-conscious and socially sensitive that this sort of event must happen all the time. Such episodes simply reinforce, however, our beliefs that we can detect when we are being watched.25

Of course, I may be wrong, and billions of people will disagree with me. After all, they have all had personal experience of the phenomenon and that’s why people believe in the supernatural. But like the invisible square we saw in chapter 1, just because we all experience something does not make it real. The most prominent and active advocate of the sense of being stared at is Rupert Sheldrake, who proposes that this ability reflects a new scientific theory of disembodied minds extending out beyond the physical body to connect together. I regard this as an idea originating from the dualism of mind and body that we discussed earlier, but such a notion has been rejected by conventional science. Undaunted by “scientific vigilantes,” Sheldrake proposes that the sense of being stared at and other aspects of paranormal ability, such as telepathy and knowing about events in the future before they happen, are all evidence for a new field theory that he calls “morphic resonance.” He proposes that it is similar to other examples of field phenomena in nature such as electric and magnetic fields.26 His idea is that the scientific evidence for morphic resonance will come from quantum physics, where the natural laws that govern the physical world as we know it no longer apply. This may turn out to be true, but for the moment I do not think morphic resonance qualifies as a field phenomenon.

The trouble is that, whereas electric and magnetic fields are easily measurable and obey laws, morphic resonance remains elusive and has no demonstrable laws.27 No other area of science would accept such lawless, weak evidence as proof, which is why the majority of the scientific community has generally dismissed this theory and the evidence. However, this has had little influence on the general public’s opinion. Science may be wrong about the reality of the sense of being stared at, but what is clear is that the public’s belief in the phenomenon is much stronger than the best measures obtained for its existence so far suggest.

BIG BROTHER IS WATCHING YOU!

The sense of being stared at reflects a common concern about being observed and monitored. George Orwell describes a paranoid world in his classic novel 1984, in which every action and belief of the citizens is controlled by the thought police overseen by the eyes of Big Brother.28 We tend not to engage in crime when we are being watched. For obvious reasons, we prefer to remain undetected. That’s part of the thrill of shoplifting by those individuals who steal items they can readily afford. The excitement is the reward, not the actual object. If we are being watched, we generally conform to social rules. People even become overtly social and more cooperative when they know they are being observed.29

Have you ever felt that pang of guilt when you have done something wrong and then wondered whether someone saw you doing it? It doesn’t have to be a real person watching you. For example, honesty boxes depend on the virtue of people to own up and pay for something if they have used it. Typically, these are the boxes in staff rooms and clubhouses that rely on members to make a fair contribution toward the cost of something, usually a hot drink. They generally don’t work that well unless there is someone watching the partakers. In one study, researchers posted either a set of human eyes or a picture of flowers above the honesty box for coffee and tea.30 On average, people paid almost three times more into the honesty box during the weeks when a picture of staring eyes was posted compared to the weeks when a picture of flowers was presented, even though there was no difference in how many cups of tea or coffee were poured. The eyes made people feel guilty about not paying for their drinks!

Sometimes the thought of someone watching us from beyond the grave is enough to make us behave ourselves. For example, students found they had the option to cheat on a computer-based exam when, every so often, the computer “accidentally” gave away the correct answer. In fact, the experimenters had deliberately programmed this to happen because they were really interested in whether participants would cheat by using this information as their answer or behave honestly on the exam. To put the students in the right frame of mind, an assistant casually told them before the test that the exam room was said to be haunted by a former student who had died there. Exam results showed that students who had been told the ghost story were less likely to cheat compared to students given no such story.31 Our sense of honesty is arguably policed by our feelings of guilt. Part of that guilt comes from the anticipated social disapproval we believe we would experience if we were found to be breaking some rule. Students who believed that a former student might have been present in the exam room were less willing to cheat.

This guilt trip theory has been used to explain why we so readily believe in an afterlife. The psychologist Jesse Bering thinks that the belief in ghosts and spirits may have evolved as a mechanism designed to make us behave ourselves when we think we are being watched.32 A guilty conscience works because it polices the way we behave, and if it can be easily triggered by the sense of others watching us, then we are more likely to act in a way that is for the benefit of the group. In the same way that students are less likely to cheat when told a ghost story, if we believe the ancestors are watching us, we are more likely to conform to society’s rules and regulations. Such a way of thinking, being advantageous to the group, would be likely to be passed on from one generation to the next. As we saw in chapter 5 on mind-reading, assuming the presence of others could be a good evolutionary strategy to always be on the lookout for potential enemies.33 And if we are hardwired to assume the presence of agents and spirits in the world, even the slightest example of a pattern that could be a face or a pair of eyes will readily be seen as such. Any bump in the night could be another person.

THE MAGIC OF MADNESS

Thinking that others are watching you and talking about you is a classic symptom of psychotic mental illness, most notably paranoid schizophrenia. Not surprisingly, supernatural beliefs are a major feature of the psychotic disorders of mania and schizophrenia. Mania is characterized by excessive energy and productivity as well as inappropriate social behavior. Schizophrenia takes a variety of forms but is generally a state in which one holds irrational and paranoid delusions and experiences perceptual distortions of reality, especially auditory hallucinations.

One characteristic of all these psychotic disorders is the sense that there are significant patterns of events in the world that are somehow directly related to the patient. This way of sensing meaningful patterns is known as apophenia, which refers to an abnormal tendency to see connections in the world that are considered relevant by the patient.34 Apophenia helps to explain the basis of psychotic symptoms such as paranoid delusions of persecution. For example, psychotic patients in the midst of a paranoid episode typically report that there is a conspiracy centered on them. They are certain that they are being watched, that people are talking about them, that their phone lines are tapped, and that generally there is a coordinated hostile campaign against them. For the sufferer, these delusions are very real and beyond rational control.

We can all sense patterns, but psychotic patients are more prone to do so and to interpret patterns as significant events related to them personally. This is supported by research that demonstrates a relationship between sensing patterns and symptoms of psychiatric disorder.35 Even adults who do not exhibit full-blown psychotic mental breakdowns, the so-called “borderline” cases, have been shown to hold a strong supersense. These beliefs are called magical ideation, and they can be measured by responses to statements such as:

“Some people can make me aware of them just by thinking about me.”

“I think I could learn to read others’ minds if I wanted to.”

“Things sometimes seem to be in different places when I get home, even though no one has been there.”

“I have noticed sounds on my records that are not there at other times.”

“I have had the momentary feeling that someone’s place has been taken by a look-alike.”

“I have sometimes sensed an evil presence around me, although I could not see it.”

“I sometimes have a feeling of gaining or losing energy when certain people look at me or touch me.”

“At times I perform certain little rituals to ward off negative influences.”

These statements are taken from a magical ideation questionnaire used by researchers to study the relationship between mental illness and the supersense.36 If you score highly on this questionnaire of thirty items, you are predisposed to psychosis. It does not mean that you definitely are psychotic or will have a psychotic breakdown, but rather that you may be at risk.

Such aspects of human nature are generally spread out across a population—a bit like height, for example. Some of us are very tall, and some of us are very small, but most of us are in the middle. It’s the same with thought processes. Some of us are more intelligent than others. Some are more anxious. Others are more depressed. Magical thinking is just the same. Psychosis can be regarded as one extreme of the distributed range of beliefs. We can all experience episodes of depression, anxiety, delusion, obsession, compulsion, paranoia, and all manner of psychiatric conditions. However, when these episodes start to dominate and control an individual’s life, they are said to be pathological. They become an illness that disrupts the individual’s well-being.

The items from the magical ideation questionnaire clearly reflect some of the pattern-detecting and intuitive beliefs that I have been describing throughout the book. Normally, we may briefly entertain such notions, but we can readily ignore or dismiss them as irrational. If we have an intrusive thought out of the blue, it does not faze us. We can inhibit the thoughts that form in our mind.

In contrast, psychiatric patients are unable to control these thought processes. They may even attribute such thoughts as coming from some other source. This is why schizophrenics often think their thoughts are being transmitted or invaded by outside signals. Everything is given significance. Consider this example taken from a schizophrenic nurse describing her first psychotic episode. The passage clearly reveals the supersense at work,

Every single thing “means” something. This kind of symbolic thinking is exhaustive…. I have a sense that everything is more vivid and important; the incoming stimuli are almost more than I can bear. There is a connection to everything that happens. No coincidences. I feel tremendously creative.37

The supersense is characterized by beliefs and experiences that lead us to infer hidden structures, patterns, energies, and dimensions to reality. We see ourselves as extended beyond our bodies and connected by an invisible oneness of the universe. Without adequate inhibitory control, we would be overwhelmed by our supersense. How do we stop these thoughts?

DOPAMINE: THE BRAIN’S SUPERNATURAL SIGNALER?

In this book, I have been arguing that the supersense is a natural product of the human brain. However, we all vary in the extent to which we experience the supersense. If it is not culture that can explain these individual differences in the way we interpret the world, there must be something in our biology that can explain this variation. At this point, I apologize to brain scientists around the world for the overly simplistic picture I am about to paint.

The brain works as a collection of cells wired together in networks to process incoming information, interpret that information, and then store it as knowledge. These various tasks are much more complicated than a few sentences can ever describe, but they all depend on networks of connected cells that communicate with each other through minute electrochemical activity. This is achieved by the neurotransmitters that form the signaling system of the brain.

Dopamine is one such chemical neurotransmitter. As the neuroscientist Read Montague says, “The dopamine system is hijacked by every drug of abuse, destroyed by Parkinson’s disease, and perturbed by various forms of mental illness.”38 Antipsychotic drugs that alleviate the florid delusional symptoms of schizophrenia are known to reduce the activity of the dopamine system, whereas administering dopamine to Parkinson’s patients, who already have impaired dopamine production, can induce hallucinations and supernatural experiences. For example, in one study the most common hallucination was the sense of someone else in the room.39 Abuse of illegal drugs such as amphetamines and cocaine can lead to supernatural experiences, and guess what? They affect the dopamine system. For these reasons, dopamine has been a source of interest for those trying to understand the supersense. If there is a smoking gun for the biological basis of the supersense, it seems to be firmly held by the hand of dopamine.40

The neuropsychiatrist Peter Brugger has proposed that apophenia represents abnormally excessive activity of the dopamine system that leads individuals to detect more coincidences in the world and see patterns that the rest of us miss.41 The idea is that dopamine acts like a filter. Too much dopamine-related activity in the brain and all sorts of patterns and significance are perceived. Too little and nothing is detected. If you score high on the magical ideation scale described earlier, you are also more likely to detect patterns and sequences than those who score low. In other words, skeptics and believers differ not only in their supersense but also in how they perceive the world.

Skeptics and believers may also differ in the activity of their dopamine systems. For example, imagine watching your TV when the antenna is not plugged in. The fuzzy snow on the screen is like visual noise. If you were to put a very faint image of a face against such a background, believers would be much more likely to say that a face was present compared to skeptics, who require more evidence of a face. Skeptics more often reject the presence of a target when it is really there. That’s because skeptics and believers have different thresholds.42 To test this, Brugger and his colleagues asked skeptics and believers to detect words and faces presented on a computer screen among lots of visual noise. The researchers then administered the drug levadopa to raise dopamine levels in both groups. The skeptics now saw patterns, but the believers were more conservative. The dopamine changed the setting on the filter for those in these two groups. Changing levels of the neurotransmitter had altered each participant’s perception.43

The research into the brain mechanisms of the supersense is intriguing but hardly surprising. We know that reality can be easily distorted by changing brain chemistry. Hallucinogenic drugs induce fantasy states in which all sorts of supernatural experiences can occur. That’s why mind-altering substances and rituals have been so important to religious ceremony. Whether through poisonous plants or trance-induced rapture, altering the brain alters reality.

An altered sense of reality may be the reason why psychotic mania has often been linked to creativity. The tendency to seek and perceive patterns where the rest of us see nothing may be part of the creative process. Some of the world’s most creative artists, writers, composers, and scientists have been associated with periods of mania, and many have had full-blown psychotic breakdowns. Listing some of them is like compiling a who’s who of the creative world: Van Gogh, Beethoven, Byron, Dickens, Coleridge, Hemingway, Keats, Twain, Woolf, and even Newton—all experienced episodes of mania. Creativity may be a benefit of the supersense, but the price we sometimes pay is potential mental illness.

However, we don’t have to suffer from psychiatric illness to assume that the supersense is operating in the world. Rather, sensing patterns and connections is part of the normal process, but we must also learn to ignore patterns and connections that may not really exist. Supernatural thinking may interfere with our ability to act rationally, as when we assume the presence or activity of unseen events in the world when they are not really there. To overcome this problem we need to exercise some form of mind control.

MIND CONTROL

The supersense may result from a mind designed to infer invisible structures in the world, but not all of us succumb to the idea that the supernatural is real. Many of us can ignore such intuitive reasoning. How can this be? Consider again some of the phenomena outlined in this book. Why does a child search over and over again for a fallen object directly below? Why do children have a problem understanding that things that look alive are not really so? Why are children’s intuitive theories about how vision works difficult to ignore? Why can we not ignore someone else’s gaze? Why might childish intuitive misconceptions lie dormant in the adult only to reappear later in life? Why do we fail to ignore silly thoughts? Why do psychotic patients detect all manner of significant patterns in the world? In all these situations, there is something about how the mind organizes and controls what we do and think. We need mind management to stop ourselves getting stuck in routines and thoughts.

Scientists interested in understanding how the mind works have increasingly become interested in the developing front part of the brain. In terms of sheer size, the frontal parts of the brain are enormously expanded in the human species. This explains why our foreheads are so much bigger in comparison to other primates and prehominid fossil skulls. Unlike our closest animal cousins, we stand out in our ability to plan and coordinate behavior and thoughts in a flexibly adaptive way. We can anticipate events and imagine solutions. Our frontal brains being what they are, we could easily beat other monkeys, apes, and Neanderthals at rock, paper, and scissors.44

One region of the frontal lobes has been a prime focus of interest: the dorsal lateral prefrontal cortex, or DLPC. The DLPC plays a major role in controlling a set of operations known as the executive functions of the brain, which include:

- Working memory: The ability to hold temporary thoughts in mind without necessarily committing them to memory

- Planning: The ability to anticipate future events and organize a corresponding sequence to achieve goals

- Inhibition: The ability to ignore distracting or irrelevant thoughts and actions

- Evaluation: The ability to weigh up thoughts and actions in terms of desired goals45

Working memory does exactly what the term implies.46 It allows you to work out problems by holding on to information in a temporary memory store. You use working memory every time you have to remember a new telephone number or someone’s name at a party. Information in working memory is only briefly held in store. It’s a store that is fragile and limited. That’s why it can be very hard to remember very long telephone numbers unless you rehearse them by repeating them over and over. Working memory is like a temporary back of a mental envelope we use when we want to take note of something briefly.

Planning is how you achieve your goals. It allows you to imagine and build mental models to play out different scenarios in advance. For example, consider this brain-teaser: You have a fox, a chicken, and a bag of corn to transport across a river but you only have enough space in the boat for one item on each trip. How do you transport all three across the river without losing any items? Remember foxes eat chickens and chickens eat corn, so you can never leave any of these pairs alone on the bank. To solve this you need planning.47 You can imagine the consequence of the first trip, the second trip, and so on until you work out the solution. If you don’t know the answer to this one, it requires taking the chicken back and forth over the river more than once.

Inhibition is another important operation of the DLPC. We need inhibition to cancel inappropriate thoughts and actions. For example, quickly say out loud the color of the ink—black, white, or gray—for the following words as fast as you possibly can.48

This should be relatively easy. Let’s make it easier still.

Okay, so you’re an expert now. Try to say the color of the word in the next list as fast as you can.

Did you make any mistakes? Maybe not, but I bet you had a problem and were much slower. The act of reading triggers the impulse to utter the word as read, but if the word conflicts with the correct answer, that response has to be ignored in order to state the color. On the other hand, naming a color is not automatically triggered by reading. So saying the word needs to be suppressed or inhibited in order to make the correct response. This is why inhibition is necessary for planning and controlling behavior: it enables you to avoid thoughts and actions that get in the way of achieving your goals.

Finally in order to benefit from all this executive function, we need to evaluate our performance. As we saw earlier, adaptive behavior can help us learn from past successes and mistakes. Remember Damasio’s frontally damaged patients in chapter 2 who were unable to play the gambling game successfully? They lacked the necessary evaluation of the hidden rules controlling the rewards. The system that learns from the past and helps us to make decisions about the future includes the DLPC. One of the main neurotransmitter systems of the DLPC is…yes, that’s right…dopamine. This may all be too convenient and simplistic, and it may be my supersense of connectedness at work, but there does appear to be a coherent pattern emerging.

We now think that brain changes in the DLPC have important implications for child development and advances in reasoning.49 Control of behaviors, thoughts, reasoning, and decision-making—in short, just about every aspect of higher intelligence that humans possess—is dependent on the executive functions of the DLPC. As we develop into adults, we become increasingly more in control of our urges, and that requires the activity of the DLPC. For example, do you remember falling objects? Which falls faster, a heavy object or a lighter one? We intuitively think that heavier objects should fall faster and are surprised if they don’t. When adults learn that this belief is wrong, measurements of their brains while they think about the problem reveal that their DLPC is active.50 When adults reason about the Linda problem from chapter 3 and consider whether she is more likely to be bank worker or a feminist, their DLPC is active trying to suppress the tendency to go for the most obvious intuitive answer.51 Even when they give the correct answer, the old childish naive theories are still active and must be suppressed. Bad ideas don’t go away. They hang around and have to be ignored!

However, like many functions of the human body, there is a progressive decline in executive functions toward old age. Many of the popular mind puzzles, like Sudoku or the current fad for “brain training” computer games, tap into DLPC abilities. When they claim that they can measure how old your brain is, they do this by comparing your performance on tasks dependent on the DLPC to the normal range that can be expected for people of different ages. That’s because DLPC function changes with age.

One consequence of the loss of DLPC control in an adult is reverting back to behaving and thinking like a young child. Whenever this system is impaired through aging, damage, or disease, the ability to remember, inhibit, plan, and evaluate is compromised. We forget things. We all know elderly relatives who seem to become socially embarrassing in their lack of control. Planning a trip becomes a chore. We may lose the ability to make rational, balanced judgments and leave all our inheritance money to “that nice lawyer who has been ever so helpful.” Old age does not guarantee wisdom.

THE CRUELEST DISEASE

For all too many of us entering old age, there can be a much more devastating and progressive slide into decline as we lose DLPC functions. Alzheimer’s disease is often considered the cruelest of diseases. The change in personality is the most distressing aspect of the illness. Someone you have spent your life knowing and loving turns into a complete stranger who needs the attention and care of a small child. Alzheimer’s is a neurodegenerative disorder, which means that it primarily destroys the higher functions that control behavior and thinking. It starts off with absentmindedness. Then there are unprovoked violent outbursts, and inappropriate behavior can alert family members that things are not quite right. The problem with diagnosing the onset of Alzheimer’s is that as we age we all change in our personality. We can become forgetful, disinhibited, grumpy, and so on, but Alzheimer’s disassembles the individual to the extent that he or she becomes unrecognizable to family and friends.

Recently, research on Alzheimer’s has provided unexpected evidence for the supersense. Before adults with Alzheimer’s reach a state of advanced decline, they display signs that the mind never truly abandons childish ways of reasoning.52 For example, when asked, “Why are there trees?” “Why is the sun bright?” or “Why is there rain?” patients give answers just like young children. They say trees are for shade, the sun is bright so that we can see, and rain is for drinking and growing. They have gone back to the teleological thinking of the seven-year-old we saw in chapter 5. They also become animists again, attributing life to nonliving things like the sun. It’s not the case that they have forgotten everything they know.53 Rather, the errors they make reflect the intuitive theories of children. Dementia shows that intuitive thinking is not abandoned but suppressed by the higher centers of the brain as we grow into adults. When that ability to inhibit is lost, the intuitive theories reappear.

BEING IN TWO MINDS

Psychologists have come to the conclusion that there are at least two different systems operating when it comes to thinking and reasoning.54 One system is believed to be evolutionarily more ancient in terms of human development; it has been called intuitive, natural, automatic, heuristic, and implicit. It’s the system that we think is operating in young children before they reach school age. The second system is one that is believed to be more recent in human evolution; it permits logical reasoning but is limited by executive functions. It requires working memory, planning, inhibition, and evaluation. This second reasoning system has been called conceptual-logical, analytical-rational, deliberative-effortful-intentional-systematic, and explicit. It emerges much later in development and underpins the capacity of the child to perform logical, rational problem-solving. When we reason about the world using these two systems, they may sometimes work in competition with each other.

The supersense we experience as adults is the remnant of the child’s intuitive reasoning system that incorrectly comes up with explanations that do not fit rational models of the world. One might assume that those prone to the supersense and belief in the paranormal are lacking in rational thought processes, but that would be too simplistic. Studies reveal that the two systems of thinking, the intuitive and the rational, coexist in the same individual. There are, in effect, two different ways of interpreting the world. In fact, when we measure reliance on intuition, no relationship has been found with intelligence. Intuitive people are not more stupid.55 They are, however, more prone to supernatural belief. One recent study found that mood is an important factor in triggering supernatural beliefs in those who score more highly on measures of intuition.56 For example, happy, intuitive adults are more likely to sit farther away from someone they believe is contaminated, a response that reflects the psychological contamination we described in chapter 7. They are also less able to throw darts at pictures of babies; this measure reflects the sympathetic magical law of similarity by which objects that resemble each other are believed to share a magical connection. Even though individuals may not be consciously aware of the thought processes guiding such behavior, these effects reveal a deep-seated notion of sympathetic magical reasoning. The supersense lingers in the back of our minds, influencing our behaviors and thoughts, and our mood may play a triggering role. This explains why perfectly rational, highly educated individuals can still hold supernatural beliefs.

Marjaana Lindeman at the University of Helsinki has recently tested this dual model of belief and reason and the role of naive intuitive theories.57 She investigated intuitive reasoning and the supersense in more than three thousand Finnish adults. First, she asked them about their supernatural beliefs, both secular and religious. Then she assessed their intuitive misconceptions. She asked them questions about animism, teleological reasoning, anthropomorphism, vitalism, and core conceptual confusions they had about physical, biological, and psychological aspects of the world—all the sorts of areas that children naturally reason about by themselves that sometimes lead to misconceptions. She asked questions like, “When summer is warm, do flowers want to bloom?” or “Does old furniture know something about the past?” Finally, she asked them which style of thinking they preferred—intuitive gut reactions or well-thought-out analytical reasoning.

When she compared adults with a strong supersense with those who were more skeptical, Lindeman found that believers were more likely to misattribute properties of one conceptual category to another. For example, they were more likely to say that old chairs know something about the past (attributing mental property to inanimate objects) or that thoughts could be transferred to others (attributing physical properties to mental states). They were teleologically more promiscuous and inclined to animism as well as anthropomorphism. They were also more vitalist and had a sense that things are connected in the world. Were they less educated? No. These were university students. What’s more, they scored just as high as the skeptical students on other measures of rationality. Rationality and supernatural beliefs can coexist in the same individual. These students were SuperBrights who simply preferred, or were more inclined to rely on, their intuitive ways of thinking.

Finland may have one of the highest rates of atheism in the world, but this large study of adult students proves that educated people do not neatly divide into those with a supersense and those without one. When people rely on their fast, unlearned gut responses, they are inclined to use their supersense, and it’s something that is easily triggered in most of us.

WHAT NEXT?

When I was a child, I spoke as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child: but when I became a man, I put away childish things.

—CORINTHIANS 13:11

Throughout this book, I have been arguing that beliefs in the supernatural are a consequence of reasoning processes about natural properties and events in our world. This includes a mind design for detecting patterns and inferring structures where there may be none. Our naive theories form the basis of our supernatural beliefs, and culture and experience simply work to reinforce what we intuitively hold to be correct. This is why the sense of being stared at is such an interesting model for the origin and development of supernaturalism. Children are not told that humans can detect unseen gaze. In fact, it’s not something they readily report that they can do. Nevertheless, young children and many adults think that vision works by something leaving the eyes. So when they experience episodes of seeming to detect unseen gaze, this belief simply emerges naturally as an unquestioned ability. It is not even considered supernatural by most people. Children were not told to think this. This model shows how the combination of intuitive theories, pattern detecting, and eventual support from culture produces a universal supernatural belief.

I think that something very similar may be going on for other supernatural beliefs. The notion of psychological contamination we examined in earlier chapters emerges naturally out of psychological essentialism, which has its roots in our naive biological reasoning. Again, this way of thinking is not something that we teach our children. Intuitive dualism and the idea that the mind can exist independently of the body is another. All of these ways of thinking are both naturally emerging and yet supernatural in their explanations of the world.

As we noted earlier, some have argued that adult supernaturalism is a product of religious indoctrination of our children. However, I hope I have convinced you that the various secular supernatural beliefs we have examined throughout this book seem to arise spontaneously without necessarily being started by religion. Most importantly, some beliefs remain dormant, whereas others that are not regarded as supernatural grow in strength. This occurs even in highly educated adults. We can all entertain weird and wonderful beliefs about the world.

We may put away childish things, as Corinthians suggests, but we never entirely get rid of them. Education can give us a new understanding and even progress to a scientific viewpoint, but development, distress, damage, and disease show that we keep many skeletons in our mental closet. If those misconceptions involve our understanding of the properties and limits of the material world, the living world, and the mental world, there is a good chance that they can form the basis of adult supernatural beliefs.

As children discover more about the real world, they should progress to a more scientific view of the world. Clearly, this does not necessarily happen. Most adults hold supernatural beliefs. The supersense continues to influence and operate in our lives. It may even give us a sense of control over our behaviors. As we saw in the opening chapters, many of our actions, whether we are avoiding a cardigan, demolishing a house, touching a blanket, or engaging in exam rituals, give us a psychological way of dealing with things. Without these beliefs, we may feel vulnerable. We may not even be aware that a supersense is influencing our lives, and yet it clearly does.

So, can we ever evolve out of irrationality? Why would such a way of viewing the world continue to flourish in this age of reason? Will the human race ever become ultimately reasonable?

I don’t believe so. There is one final piece of the puzzle that I have been hinting at throughout the book that now needs to be considered. It moves beyond the question of origins and asks: are they any benefits of the supersense? After all, if science has the potential to elevate the human species to new levels of achievement, why do we still succumb to a supersense? Part of the answer is that it may be unavoidable, as I hope you will now appreciate. Another reason is that the supersense makes possible our capacity to experience a deeper level of connection that may be necessary for humans as social animals.

Even though humans have the capacity to reason and make judgments, I think that we will always regard some things in life as not reducible to rational analysis. That is because society needs supernatural thinking as part of a belief system that holds members of a group together by sacred values. In the final pages, I will explain how this supersense forms the intuitive rationale for the sacred values that bind our society together.