Three

RAISING THE RANGERS, 1776

ROGERS DID NOT WASTE TIME IN RAISING HIS BATTALION, WHICH HE named the Queen’s American Rangers. It was intended for active service in the field and not for local self-defense, which was the purpose of several other Loyalist battalions being raised at the same time. He followed the colonial system of awarding commissions based on the number of recruits that aspirants brought in. Generally, warrants were issued to those who wanted commissions, giving them the authority to recruit for His Majesty’s service. This included promising a forty-shilling bounty to each new recruit, plus a proportionate share of rebel lands at the conclusion of the rebellion. But this system of recruiting provided no assurance that the men who were commissioned in this manner possessed the quality and character to become effective officers. Very few of them even had any prior military service.1

There were many Loyalist refugees on Staten Island in August 1776. At least half the battalion was complete by August 27 when the British army, which had started crossing over to Long Island on August 22, launched their attack on the American army encamped on the island. John Brandon, proprietor of a New York City tavern and former soldier in the French and Indian War, received a commission as captain on August 20. He fled the city in May 1775 due to mob action and went to Boston, where he was commissioned as a lieutenant by Lieutenant General Thomas Gage, in the Loyal Irish Volunteers. He went with the British to Halifax upon the evacuation of Boston and followed them back to New York City in July 1776. Ephraim Sanford, former resident of Salem in Westchester County, received his commission as captain on August 21. John Griffiths, former resident of Pills Town, near Albany, New York, and more recently the proprietor of a dram ship in New York City, was commissioned a captain on August 23. He had some prior military experience as captain of a volunteer company during the previous war. John Eagles, a former resident of White Plains in Westchester County, became a captain on August 25. Daniel Frazer, a sergeant in the 46th Regiment of Foot, and a veteran of twenty-three years of service, was recommended for a lieutenancy in the rangers by Major General Sir John Vaughan. Since he subsequently raised a full company, he received a captain’s commission instead on August 26. Patrick Walsh, veteran of twenty-three years in both regular and provincial service, was a New York City constable at the time of his appointment as lieutenant and adjutant on August 19. Rank-and-file for the newly raised companies were obtained not only on Staten Island itself but through furtive recruiting on Long Island, New York, Connecticut, and New Jersey shores. After the American army retreated across the East River to New York, following their disastrous defeat on August 28, the rangers moved over to Long Island and encamped in the general vicinity of Jamaica and Flushing. There, recruiting and training continued.2

Recruiting could be a dangerous business, sometimes leading to capture or death. One man, William Lounsbury of Westchester County, with a warrant from Rogers authorizing him to recruit a company, was killed near Mamaroneck on August 30, and fourteen of his new recruits were captured. He was betrayed by an associate who informed the local Patriot militia of his presence.3

The ranger recruits were a mixed breed, most without any prior military experience. Some were men of principle, who refused to abandon their loyalty to Great Britain. Others were adventurers looking for gain or excitement. Some were even obtained from jails, such as the one in Flatbush, Brooklyn; others were tricked into enlisting, such as young Timothy Resseguie, of Connecticut. He and several others of Loyalist persuasion were told by a secret recruiting agent that the latter would make arrangements for them to be taken over to Long Island to be safe under British protection and away from rebel harassment. They were instructed to write their names in a book, ostensibly for the purpose of providing evidence to show the British authorities how many boats would be needed to bring the Loyalists across. Later, the agent wrote enlisting orders over their names and turned them over to Rogers upon their arrival on Long Island. Such tactics were resorted to because, in the early days at least, many deserted after collecting their bounty of forty shillings, and replacements were constantly necessary to maintain company strength. If replacements were not recruited, the unit risked being dissolved. Rogers could not let this happen. This command would likely be his last opportunity to redeem himself from the failures he had encountered over the past several years.4

Refugee Loyalists from Connecticut and Westchester usually landed at Lloyd’s Neck, near Huntington, where a post was maintained to receive them. Patriot governor Trumbull of Connecticut feared that Rogers might attack the towns of Greenwich, Stamford, and Norfolk, since many of these Connecticut Loyalists knew every inlet and avenue into these towns.5 Rogers’s reputation from the French and Indian War was that of an aggressive and determined fighter. His name still conjured visions of waylaying, ambuscade and sudden attack.

On September 15, the British crossed over from Newtown Creek on the Long Island shore and landed at Kip’s Bay (east end of 34th Street). The rangers stayed behind at Jamaica. The skirmish at Harlem Heights occurred on September 16, and ended in a draw. The Americans entrenched themselves on the Heights while the British set themselves up in the city, which in 1776 occupied an area of only a square mile.6

Between midnight and one o’clock in the morning on September 21, a fire broke out in New York. It started in a small wooden house on a wharf near the Whitehall Slip and spread quickly to nearby buildings. Many of the houses in the area were of wood and covered with cedar shingles. The burning flakes of the shingles, being light, were carried by the wind some distance and, falling on the roofs of other houses, kindled the fire anew. The venerated Trinity Church on Broadway caught fire and was completely destroyed. St. Paul’s Chapel, farther north on Broadway, however, was spared. Attempts to fight the fire were unsuccessful, as the fire companies were undermanned and much of the fire equipment was out of order. British soldiers and sailors were pressed into service to pull down such buildings as would conduct the fire. At about 2 A.M., the wind veered from the southwest to the southeast and drove the fire away from the main part of the city. By the time the fire was finally checked, between ten and eleven o’clock, a total of 493 houses had been destroyed. This loss of quarters for soldiers and civilians put a great hardship on the city for the remainder of the war. New York became a tent city, not only to house much of the existing population, but also the many future refugees that were to escape from the American rebels to the protection of the city and the British army. Many British soldiers and Loyalists believed the fire had been started by the Americans, though to this date there is no clear evidence to indicate who was responsible or how it started. All outposts were put on alert to look for suspicious individuals.7

The Queen’s American Rangers patrolled the north shore of Long Island. They worked in conjunction with the British ten-gun brig Halifax, commanded by Lieutenant William Quarme, which patrolled the Sound. While patrolling the shore, Rogers kept his eye out for any suspicious individuals who might be rebel spies or agents. One particular individual, a young man, came to his attention. He had recently appeared asking many questions of the local inhabitants. Rogers therefore decided to pay a visit to this young man’s quarters at a local tavern, and struck up a conversation with him concerning the war. Rogers intimated that he was “upon the business of spying out the inclination of the people and the (movements) of the British troops.” He must have been a very naïve individual, for he accepted Rogers’s statement at face value and indicated he had similar reasons for being on Long Island. This revelation confirmed Rogers’s suspicions that the young man was an American spy.

Rogers extended an invitation for the young man to dine with him the following day, September 21, at Rogers’s own quarters, and the invitation was accepted. When the young man showed up the next day, he met Rogers. The latter was accompanied by three or four associates, intended to serve as witnesses, whom Rogers introduced as fellow American sympathizers. They all sat down to dine, and the conversation again returned to what the young man and Rogers had discussed the previous day. At the height of the conversation, Rogers apparently gave some signal, and a detachment of rangers entered the tavern and placed the young man under arrest. The young man denied the accusations made against him, but to no avail, as the disturbance drew the attention of some Loyalist refugees from Connecticut, who recognized the young man as also being from Connecticut and identified him as Captain Nathan Hale of the Continental Army. Hale was taken to New York the following morning, convicted as a spy, and hanged at eleven o’clock in the morning in Battery Park.8

By the end of September, the battalion was relatively complete, and an executive officer, belonging to the Virginia gentry, was posted to the rangers on September 25 with the provincial rank of major. His name was John Randolph Grymes. This individual raised a small cavalry troop to assist Lord Dunmore, the last royal governor of Virginia, in the latter’s failed attempt to keep Virginia in the royal camp. He arrived on Staten Island, along with Dunmore and other refugee Virginia Loyalists, just prior to the Battle of Long Island. It was probably with Dunmore’s influence that he was posted to the battalion.9

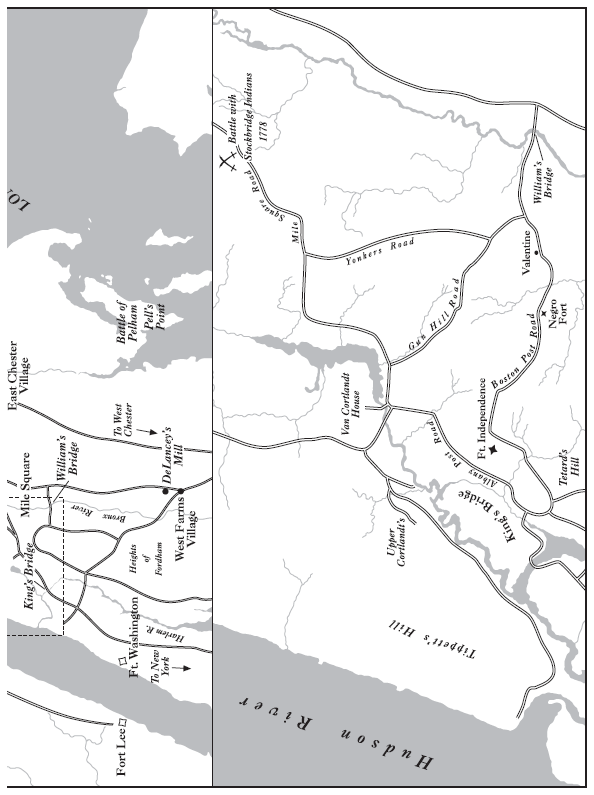

The rangers continued to remain on patrol duties on the North Shore until Saturday, October 12. On that date, General Howe embarked a force consisting of the Light Infantry, 1st, 2nd, and 6th British Brigades, two Hessian brigades from Manhattan, the 71st Highlanders, the eight companies of Rogers’ Rangers, and one company of the New York Volunteers, under Captain Alexander Grant, from Long Island. A total of about eighty vessels were used to convey the expedition. They landed on Throg’s Neck at 9 A.M. without the smallest opposition.10

The British force marched about three miles to a causeway and bridge that led from the neck (actually a peninsula) to the Bronx mainland. This bridge and causeway were situated about a mile from Westchester Village (today the Westchester Square section of Bronx County). The British advance guard was met by rifle fire from a detachment of the 1st Pennsylvania Rifle Regiment, who took up the planks of the bridge and concealed themselves behind a woodpile. The American detachment was quickly reinforced until it totaled about one thousand eight hundred men. Both sides dug in and engaged in repeated skirmishing across Westchester Creek for six days.11

On October 16, Howe decided to re-embark his forces and proceed to a new landing at Pell’s Point (today part of Pelham Bay Park). The British and Hessian regiments were ordered to strike their tents at 3 A.M., load their wagons, and be in readiness to march immediately. The rangers and Grant’s Company were to form in the rear of the 42nd Highlanders. On the following day, seventy-two rangers were temporarily detached to serve with the artillery attached to the light infantry and grenadiers. Three men each were assigned to handle each three-pounder and eight men each to handle each six-pounder. In addition, another one hundred twenty rangers were to carry a hundred fascines (a bundle of sticks tied together and used in building earthworks), plus forty entrenching tools, under the direction of a British engineering officer.12 They were undoubtedly detailed to this duty, as they were green troops and the British were reluctant to use their own experienced soldiers for this effort.

The landing at Pell’s Point was made on October 18. On this same date, the main body of the American army evacuated Harlem Heights and headed north to White Plains, leaving a garrison of two thousand men at Fort Washington (eastern site of the George Washington Bridge). The only American force at Pell’s Point to oppose the British landing was a small brigade commanded by Colonel John Glover, consisting of about seven hundred fifty men with three field pieces. Glover was posted at Eastchester Village (today’s Mount Vernon), and marched his men forward to meet the British landing force.

About a mile from the Point, the Americans took position behind stonewalls lining the road. Their advance guard met with the British advance guard, and firing issued. The British subsequently withdrew to wait for their main body. When the latter arrived at the Americans’ position, they were greeted by repeated volleys from behind the stonewalls. The Americans fired by platoons and each platoon retreated and took position farther back, where they had a chance to reload and continue firing at the advancing British. The Americans eventually broke off the action under heavy fire of British musketry and retreated to a nearby hill. Both sides engaged in an artillery duel until nightfall, and the Americans slipped away after dark. The Americans reported eight killed and thirteen wounded. The British reported three killed and twenty wounded.13

The British army encamped at Eastchester Village on the night of October 19, 1776. Howe set up his headquarters in Pelham Manor opposite to Eastchester. The right wing of the army was extended toward New Rochelle.14

On October 20, the one hundred twenty men of the rangers, on duty with the British engineers, were returned to Rogers. At 6 A.M. on October 21, the British army marched three miles to New Rochelle. The rangers were in the vanguard, and Captain John Eagles’s company was the first to enter the town. After the rest of the army arrived, Rogers was ordered to take his rangers (exclusive of the seventy-two men with the British artillery) up the Boston Post Road to Mamaroneck to destroy a supply of provisions that the Americans had abandoned on their retreat to White Plains. A company of British grenadiers and a company of Hessian jägers were sent along with the rangers as additional reinforcements in case of resistance. When Rogers arrived at Mamaroneck, he detached part of this force to take possession of the high ground, where they could guard the rest of the force against any sudden surprises. He took the remainder into the village, and the militia, guarding the stores, fled at his approach. The rangers then began destroying great quantities of rum, flour, pork, etc., in the houses and barns located on the landing near the waters of Long Island Sound. After the mission of destruction was completed, the Hessian and British companies returned to the British army encamped at New Rochelle.15

The rangers remained at Mamaroneck on outpost duty, and Rogers decided to set up his encampment on level ground atop Heathcote’s Hill. The latter was the site of a fine mansion built by Colonel Caleb Heathcote, Lord of the Manor of Scarsdale and a member of the Royal Council for the province of New York, who had died in 1721. The campsite had formerly been part of an ornamental garden that had been abandoned.16

The rangers had no tents, and bivouacked around fires made from the rails of neighboring fences. Rogers posted several sentries on the Mamaroneck Road (now Mamaroneck Avenue) leading northwest to White Plains to guard against possible attack from that direction. One sentry was posted to guard the southwest approach, which consisted of open fields. Rogers himself set up his headquarters in a schoolhouse just west of the Boston Post Road and south of Heathcote Hill.17

News of the presence of the Queen’s American Rangers at Mamaroneck was reported to Brigadier General William Alexander, commanding the advance force of the American army at White Plains. The report was made by Colonel Rufus Putnam, chief engineer of the American army, who had been on a scouting mission in the vicinity of New Rochelle. Alexander decided to send Colonel John Haslet with his Delaware Regiment of six hundred men, plus a detachment of one hundred fifty men from the 1st and 3rd Virginia Regiments under Major John Greene of the 1st Virginia, to attack Rogers.18

Sometime after midnight on Tuesday, October 22, Haslet and his force of seven hundred fifty men departed the American encampment at White Plains and proceeded, by forced march, to Mamaroneck, a distance of six miles. They came down the White Plains–Mamaroneck Road but took a detour halfway, still going southeast but south of the rangers’ position. They entered onto a parallel road called the Quaker Meeting House Road (now Weaver Street). They followed this road to within a half mile of the Boston Post Road and then turned northeast, advancing across an open field for three-quarters of a mile until they came onto a lane, which led into the fields from the Boston Post Road. This lane was normally only used by farmers for bringing their cattle into the fields for grazing. A lone ranger picket was stationed near this lane, west of the camp.

The picket was seized before he could give an alarm. The vanguard of Virginians, under Major Greene, then charged into the camp taking the rangers completely by surprise. Captain Eagles’s company, which was stationed on the southwest portion of the camp, bore the brunt of the attack. Eagles himself was absent, as he had remained behind at New Rochelle, and the acting commander was an Ensign Hughson, a Loyalist from Dutchess County.

Some of the rangers quickly surrendered, but others seized their muskets and fought back. The darkness, and the fact that many on both sides still had no uniforms but were dressed in plain clothes, caused much confusion and made it difficult to distinguish friend from foe. Rogers quickly came from his headquarters at the schoolhouse when the firing first started and immediately started mobilizing his men to meet the attack. Eagles’s company was completely overrun, and the triumphant Americans pressed on only to be met by heavy musket fire from the rest of the now rallied rangers. Rogers directed the defense by instructing his men to hold their fire until the enemy got closer. Colonel Haslet subsequently decided to withdraw, since the rangers had recovered from their initial surprise and further fighting would yield no beneficial results.19

The Americans retreated back along the same route by which they had come. Their attack had only cost them two killed and twelve wounded, including Major Greene among the latter. The more seriously wounded had to be left behind, and some of them later died. They took with them thirty-six prisoners, about sixty stand of arms, and a pair of colors.20

The rangers suffered more heavily. Captain Eagles’s company, for practical purposes, ceased to exist. At least twenty-five of the rangers taken prisoner were from his company, and twenty-three of the others were either dead or seriously wounded. Ensign Hughson himself, the acting company commander, was killed in action.21

No pursuit was made after the retreating Americans. The green rangers were still too shook up to go on the offensive. The wounded, of both sides, required care. The wounded men remained on Heathcote Hill for the balance of the night and part of the next day, until wagons and carts could be obtained from the local farmers to relocate them to a church in New Rochelle, where medical attention could be administered. Many were beyond saving. The cries of the wounded were dreadful, with many crying out for water, screaming in pain, or burning with fever. The rangers had suffered their first baptism of fire, and it was only due to Robert Rogers’s command and encouragement that they had not broken completely.22

When Colonel Haslet’s command got back to General Alexander at White Plains, they were publicly thanked for their success. Three of the ranger prisoners, who were deserters from the American army, were hanged at noon on October 22. Twenty-eight of the remainder, being inhabitants of New York, were sent by order of the New York Convention, to Exter, New Hampshire, on November 3 for confinement.23

The inhabitants of Mamaroneck, after the withdrawal of the rangers from Heathcote Hill, subsequently found themselves with the unpleasant task of reburying the dead of both sides. The graves were not dug very deep, and roaming dogs had uncovered the dirt and begun to eat the bodies. New graves were dug and heavy stones placed upon them, to protect the remains from further violation.24

The aftermath of the affair at Heathcote Hill resulted in criticism of Robert Rogers by certain British officers, for permitting himself to be surprised by the enemy. His reputation as a partisan fighter suffered some damage, and the fact that he was not considered a gentleman by most of the British officer corps led to demands for his removal. Nevertheless, Lieutenant General William Howe kept him in command, since he had successfully defended his position against a superior force.

Rogers continued to remain at Mamaroneck, and the seventy-two men detached to the artillery were returned to him. The British army subsequently advanced on October 25 from New Rochelle to Eastchester on White Plains Road. Howe requisitioned the house of Stephen Ward, an American sympathizer, as his headquarters. Rogers received orders to take his battalion of rangers to Bedford, Connecticut, to recover British naval personnel being held captive in that town. This he successfully accomplished on October 26, bringing back six or eight officers and men.25

In addition to this rescue, he also raised upward of one hundred twenty new recruits to replace his losses and create a new company, giving him a total of nine companies numbering about four hundred fifty men.26 However, this number would constantly fluctuate, as desertions were frequent and constant recruiting was necessary to maintain strength. Many only enlisted to collect the bounty and then desert at the earliest opportunity. The Queen’s American Rangers still had a long way to go before they could be considered a disciplined military force. The provincial forces were currently left to their own devices as far as military training was concerned. Since both officers and men were basically civilians, Rogers himself saw that his men received only the rudiments of training. He himself, a fierce individualist, did not set any great store on formal military training. He believed in personal leadership and example in guiding men. However, as events would subsequently prove, he had little of this left to give.

On the morning of October 28, the British and American armies clashed at White Plains. The American army had recently been divided into seven divisions. Six of these divisions, numbering about fourteen thousand five hundred men, were stationed on a series of hills overlooking the village of White Plains. The 7th division, about three thousand five hundred men, under Major General Nathanael Greene, had been left at Fort Lee, across from Fort Washington, which was garrisoned by American colonel Robert Magaw with two thousand men.

The first firing occurred between the British advance, consisting of Hessian colonel Johann Rall’s regiment, and the division of American brigadier general Joseph Spencer, with some assistance from Major General Charles Lee’s division, which had been sent out to meet them. The Americans fought a delaying action, withdrawing each time they were in danger of being outflanked. Rall’s Hessians succeeded in driving Spencer’s troops back across the Bronx River to Chatterton’s Hill, where the former stopped when they ran into fire from other American troops encamped on that hill.

Washington’s line of defense extended from Purdy Hill on the east to Chatterton Hill, just across the Bronx River on the west. Howe elected to make his attack on Chatterton, which commanded the entire plain, being one hundred eighty feet over the river. The side was steep and heavily wooded. The top was divided by stonewalls into cultivated fields. The hill was defended by about one thousand six hundred men under Brigadier General Alexander McDougall, consisting of his own brigade, plus Colonel John Haslet’s Delaware Regiment and two militia regiments from New York and Massachusetts. In addition, the Americans had two light guns under the command of Captain Alexander Hamilton.

The British army, halted in the plain below Washington’s position, presented a brilliant and formidable spectacle to the Americans watching and waiting for the British to make their assault. It was not long in coming. The 2nd British Brigade, under Brigadier General Alexander Leslie, assisted by Colonel Carl Von Donop’s battalion of Hessian grenadiers, and the Hessian regiment of Lossberg, were assigned the task of taking Chatterton’s Hill. This force of four thousand men began forming into lines of battle, and the British artillery started bombarding the hill as a prelude to the attack.

The Hessians led the advance, and when they reached the Bronx River, they tried to construct a makeshift bridge across it but were hindered by musket fire from the defending Americans. A ford was found downstream, and the bulk of the British and Hessians crossed the Bronx at that point.

Leslie marched his men north to the base of the hill and started up the steep slope. The first attack was thrown back, but the British and Hessians reformed and started up again pushing the Americans before them. The artillery fire had ceased now that the movement up Chatterton’s Hill had started. Rall’s regiment of Hessians, which had driven back Spencer’s force, forded the Bronx and attacked the west side of the hill defended by the two militia regiments. Rall’s attack was supported by the 17th Light Dragoons, and the combination of the two broke the militia, who fled from their position. While the dragoons pursued the fleeing militia, Colonel Rall turned his attack on Colonel John Haslet’s Delaware Regiment.

The combination of attacks from Leslie in front and Rall on their flank persuaded the American general Alexander McDougall that further resistance was hopeless. The Americans retreated back across the Bronx River to the main camp, with Haslet fighting a rearguard action. No attempt, however, was made by the British to pursue them back across the river.

Reports of American casualties varied, but most returns and contemporaneous letters fix the number at about one hundred thirty. The British and Hessians suffered 231 casualties, of which 154 were British.

Lieutenant General Howe made no further move against the Americans’ pending arrival of additional reinforcements from New York. During the interval, Washington moved his sick and wounded, as well as his baggage and equipment, to a safer place in the rear. On October 30, the four regiments of the 3rd Brigade and two regiments from the 4th Brigade arrived and gave Howe a force of about twenty thousand men, exclusive of about four thousand seven hundred Hessians, under Lieutenant General Wilhelm Knyphausen. This force, which had landed at New Rochelle on October 22, and had stayed there to protect Howe’s rear, was ordered on October 29 to take possession of the abandoned Fort Independence near Kingsbridge.27

Howe prepared for an attack on Washington’s lines on October 31. However, a heavy rain began falling in the early morning, and the attack was suspended until the storm abated. The storm lasted for twenty hours, and after darkness fell on the night of October 31, Washington withdrew his army to North Castle Heights, about five miles northeast near Rye Lake. There the Americans started throwing up fresh entrenchments to meet future British attacks.28

The advance guard of the British army engaged the retreating Americans during the night of October 31 and the early morning hours of November 1. The rangers were part of the advance force, and engaged in skirmishing with elements of American brigadier general George Clinton’s brigade of Major General William Heath’s division. Ranger lieutenant John Dean Whitworth, a native of Waltham, Massachusetts, was captured on October 31 and subsequently sent to Boston for confinement. During the early morning hours of November 1, some of the rangers, advancing through the village of White Plains, fell in with a detachment of American rangers under a Captain Van Wyck on North Street. During the ensuing fight, the American captain was killed with a musket shot through the head, but his assailant was in turn shot by other Americans. The rangers subsequently forced the withdrawal of the rest of the American detachment. At 9 A.M., the village of White Plains was in full possession of the British army.29

General Howe moved his headquarters from Ward’s House to White Plains. For five days, the British army remained encamped in the vicinity while Howe tried to decide whether to attack the new American lines. These lines were not formidable and could have been overrun with determined effort. But Howe, always cautious, decided not to launch an assault, and on November 5 gave orders for the army to march instead to Dobbs Ferry near the Hudson.30 The Westchester campaign was over, with no victory having been achieved by either side. Washington was again given the necessary time to regroup his army in order for it to continue the fight another day.