Thirty

THE SIEGE OF YORKTOWN AND GLOUCESTER

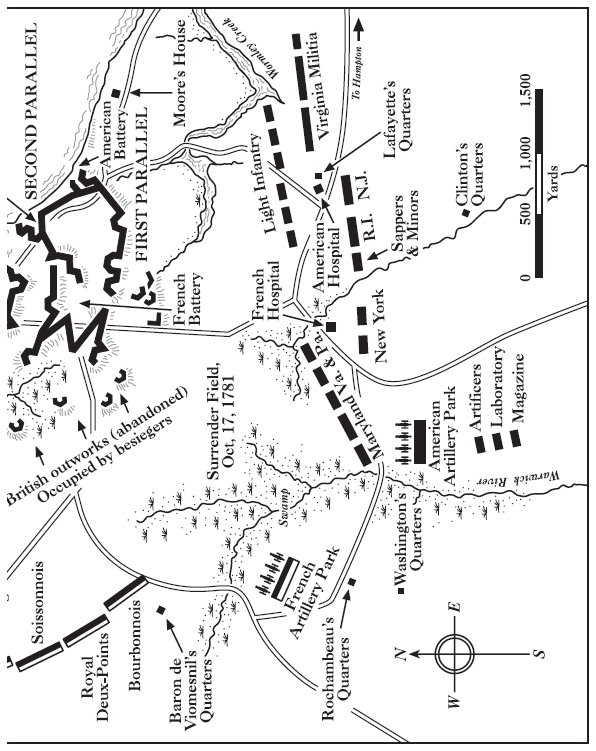

ON SEPTEMBER 28, 1781, WASHINGTON AND ROCHAMBEAU STARTED their advance from Williamsburg toward Yorktown, just twelve miles away. The French moved forward at about 5 A.M. organized into three separate brigades, with the French grenadiers and chasseurs in the van. They followed behind the Americans organized into three Continental divisions of two brigades each plus two small brigades of Virginia militia. The Americans took a position on the right, southeast of the town, with two divisions on each side of the road from Hampton. The third division positioned themselves along Beaver Dam Creek. The French positioned themselves on the left, with one French brigade occupying a position north of the road to Williamsburg and the other two brigades just south of the same road, all facing Yorktown on the east. Major General Benjamin Lincoln commanded the American right wing (8,845 rank and file) with Rochambeau commanding the French left wing (7,800 rank and file).1

The aforementioned encirclement started around noon but was still incomplete by evening. Tarleton, who was on the east side of the road from Hampton with his British Legion cavalry and attached mounted infantry, organized his men into three squadrons to dispute Lafayette’s division, which was facing him. However, no opportunity offered itself that might enable him to seriously hinder Lafayette, and Tarleton subsequently withdrew his cavalry to the Moore House, located south of the town on the York River, to await further developments.2

On the following morning, the encirclement was complete. Causeways had been constructed over the various morasses during the night, enabling the Americans to reach their assigned positions. No offensive moves were made that day by the British other than a few cannon shot from the British field battery on the Hampton Road and skirmishing by pickets belonging to the British light infantry and Anspach battalions.3

On the evening of September 29, Cornwallis received another communication from Clinton, dated September 24, again reassuring Cornwallis of eventual reinforcement, which hopefully would leave New York on October 5. Cornwallis chose that same night to abandon his outer works, except for the Fusilier’s Redoubt, and withdraw to the inner ones in order to more easily prolong the defensive until relief arrived. Those abandoned works were then occupied by the French and Americans the next morning, and enabled them to approach even closer toward Yorktown. Tarleton was quite critical of this action by Cornwallis, and considered that holding the outer works would have better facilitated the defense of the town, by holding up the allied army and permitting the inner redoubts to be placed in a greater state of defense.4

September 30 was spent by the French and Americans in moving up to and just past the main road from Williamsburg. An advance by the French light infantry toward the Fusilier’s redoubt, held by the 23rd Regiment, was repulsed with light casualties. The only other action of the day was a reconnaissance by Lieutenant Allen Cameron of the British Legion, with a detachment of same, who skirmished with a similar party of American light infantry–which he successfully dispersed, taking a number of prisoners, including Colonel Alexander Scammel of New Hampshire, who was mortally wounded in the process. He was taken back to Yorktown for treatment of his wound. He was later released on parole to Williamsburg but died the following day.5

The opposing armies were now less than two miles apart. On the night of September 30, ground was broken for the building of additional French and American redoubts. These redoubts were to become part of the first parallel or siege line, and were completed by the night of October 6, six hundred yards (one-third of a mile) from the British works. It extended for one to two thousand yards from some high ground above the York River south of the town to just west of the road to Hampton, connecting with the abandoned British outer works.6

Trenches connecting the redoubts were occupied by the French and Americans as soon as they were completed. British artillery kept up a frequent, if not constant, fire on allied working parties, to impede the building of the parallel and the setting up of batteries. Nevertheless, by the afternoon of October 9, the French and Americans completed their preparations and were ready to start the cannonade of Yorktown, which up to now had been spared from any physical destruction.7

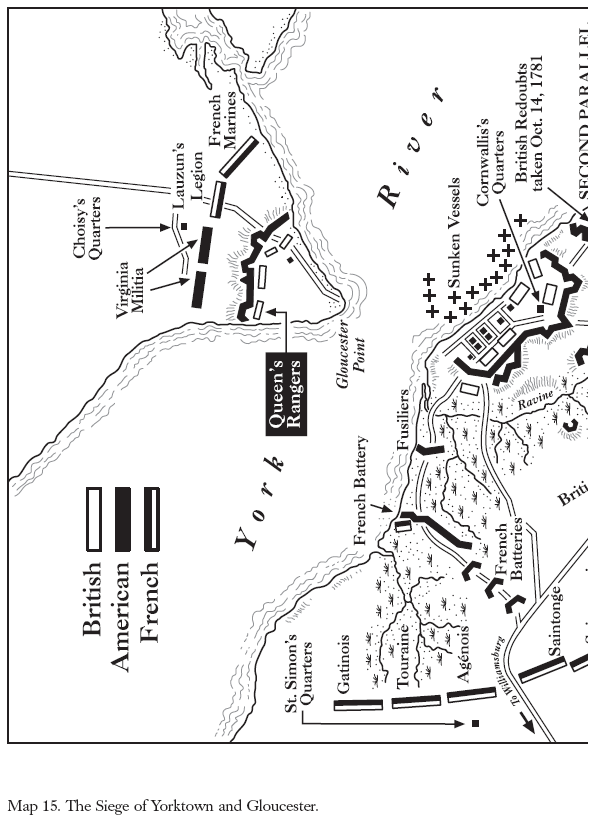

Three days before the completion of the first parallel at Yorktown, Brigadier General Marquis de Choisy, over at Gloucester Point, moved his troops closer to the British redoubts on Gloucester. Unknown to him, the garrison at Gloucester was reinforced the night of October 1 by Tarleton with his British Legion and mounted light infantry numbering close to three hundred men. Cornwallis considered that cavalry would subsequently be of more use on the Gloucester side, in keeping open his only possible route of escape.8

On the morning of October 3, Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Dundas, commanding at Gloucester, decided to personally lead a detachment of combined infantry and cavalry on the first foraging expedition since September 24, out into the countryside in the direction of the distant French and American lines. After proceeding about three miles from Gloucester, the wagons and bat-horses were finally loaded with Indian corn, and at about 10 A.M. the return trip was started. The infantry of the detachment provided close escort to the wagons and bat-horses, while the cavalry under the command of Tarleton served as rear guard some distance behind. The return march did not proceed far before Lieutenant Allen Cameron, patrolling with some Legion dragoons in the rear of the march, sent a message that several mounted militiamen had been spotted. This was followed a short time thereafter by another report that a large party of French hussars was sighted and moving up fast.9 The cavalry of the Duke de Lauzun’s Legion (three hundred dragoons) moving in two detachments, led the advance of de Choisy’s march toward Gloucester. About four miles from the town, a detachment of mounted militia dragoons, on scouting duty, rode up and announced the British presence less than a mile away. Lauzun and his hussars, some armed with spears rather than swords, galloped forward to meet the British cavalry.10

At the time Lauzun and his cavalry received the above news, they reached a road with a lane in front, near a mile in extent. At the end of this lane, Lauzun saw on his left a wooded area, which extended for about a mile, at the end of which was a small advanced redoubt commanding the road. On his right was an open field, at the end of which, at a right angle with the main road, was a post and rail fence. In advance of this redoubt and fence was Tarleton’s cavalry, plus three attached troops of about a hundred Queen’s Rangers cavalry under Captain David Shank. Simcoe himself was not with his cavalry as his health had deteriorated to such an extent that he was no longer able to take the field.11

Tarleton quickly formed his cavalry command of about four hundred horsemen to meet an attack as soon as the French cavalry was seen. The Queen’s Rangers formed the left of Tarleton’s line with the British Legion on the right and the mounted infantry in the center. After the line had been formed, Tarleton rode forward with Lieutenant Allen Cameron’s party of Legion dragoons, to reconnoiter the situation.12

The hussars of the Duke de Lauzun’s legion charged forward to strike at this tempting target. Lauzun and Tarleton caught sight of each other and attempted to personally come to blows. However fate intervened. A British Legion horseman riding alongside Tarleton had his horse struck by a lance, which caused the wounded animal to fall against Tarleton and his mount, knocking them both to the ground.13 Seeing Tarleton fall, the rest of the British cavalry moved forward to join battle with the French and to attempt to rescue their commander. They arrived in such disorder, however, that they were unable to achieve any real success against Lauzun’s men. Tarleton, after seizing and mounting another riderless horse, took stock of the situation and ordered a withdrawal in order to regroup.14

The French continued to follow and in order to hold them up, Tarleton ordered about forty of the mounted infantry to dismount, take a post in the nearby wood and temporarily hold up the French until the British cavalry could complete their regrouping. The party of dismounted infantry under Captain Forbes Champagne of the 23rd Regiment, aided by other regular infantry, concealed themselves behind the post and rail fence. They managed to halt the French cavalry and force them to fall back.15

Lauzun withdrew his cavalry back to the vicinity of the enclosed field in order to regroup his own men to make another charge. They fell behind a small battalion of about one hundred sixty Virginia militia raised and trained by its commander Lieutenant Colonel John Mercer, which just arrived on the scene. Mercer deployed part of his command in the woods, and prepared to dispute the British infantry and cavalry if they decided to charge before Lauzun could make his own cavalry attack.16

Tarleton formed up one hundred fifty cavalry to hit the French in the front. The light infantry were assigned to make a flanking attack. The infantry advanced through a wooded area, which provided some concealment of their approach. A withering burst of fire hit them when they came within one hundred fifty yards of Mercer’s position. The cavalry in turn were also hit when they were within two hundred fifty yards from where the militia had positioned themselves. The order for the British cavalry to charge the French and American line was never given by Tarleton.17 Instead he ordered a retreat on the mistaken assumption that the newly arrived militia force was much larger than it actually was. Tarleton did not want to risk his command in attacking what he believed was a large body of infantry coming to the support of Lauzun’s cavalry. This action was Banastre Tarleton’s last of the war, and the only one where he exercised any discretion, though it was mistaken. His defeat at Cowpens may have left him cautious against making headstrong charges with no reasonable guarantee of success.

The British loss in this affair was one officer and eleven rank-and-file killed or wounded. The French loss was three rank-and-file killed and two officers and eleven rank-and-file wounded. Whether Mercer’s militia incurred any casualties remains unknown, as none were officially reported.18

Dundas and Tarleton retired within the works at Gloucester. The infantry of Lauzun’s Legion arrived at the scene of battle a half-hour after the last shot had been fired. The French marines and the remaining militia came up later. That evening one hundred fifty French and one hundred fifty Americans took possession of the advance redoubt, and de Choisy’s advance forces encamped within a mile and a half of the main Gloucester redoubts. De Choisy restricted future activity to intermittent skirmishing and frequent patrols to prevent anyone from attempting to escape the tightening net.19

Several days later, on October 12, Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Dundas crossed the York River over to Yorktown with his 80th Regiment. He left behind a detachment of eighty-four men to help man Redoubt Number Three. The rangers were at Redoubt Number One, the British Legion at Redoubt Number Two, and the Hessian jägers were at Redoubt Number Four. Tarleton assumed command of the Gloucester garrison, in lieu of Simcoe, his senior in rank, who was too ill to take over this duty. Simcoe felt great concern for his rangers, many of whom, among the rank-and-file, were deserters from the American forces. Uncertain as to what fate might be in store for this particular group, and harboring a general dislike of having to possibly surrender a corps into which he had invested much time and effort, Simcoe hoped to lead his men in a breakout before the latter became a certainty. He discussed this desire with Cornwallis, but the latter refused permission, stating that the army must share one fate.20

On the Yorktown side of the river, the siege had begun in earnest with the start of the French and American artillery barrage on the afternoon of October 9. The allied batteries, along this first parallel, opened up about five o’clock in the afternoon and continued intermittently for the next two days. The British works and fortifications received considerable damage and many buildings in the town itself were destroyed. The ricocheting of bombs and howitzers caused many deaths and inflicted serious injuries. Cornwallis reported to Clinton on October 11 that he had lost a hundred killed or injured in the first forty-eight hours of the bombardment.21

On October 10, Cornwallis received the last letter sent to him by Clinton during the siege. It was written on September 30 and stated that reinforcements were expected to sail on October 12, if the winds should permit. The letter was brought to Cornwallis by Major Charles Cochrane, former commander of the British Legion infantry and presently an aide to Cornwallis. Cornwallis wrote back on October 11 that time was of the essence, and that he could not expect to hold out for very long against the heavy allied artillery.22

During the night of October 11, the barrage declined in intensity in order for the French and Americans to begin building the second parallel three hundred yards from the British works. The British artillery resumed limited firing in order to hinder this activity as much as possible. Cornwallis was convinced that, once the second parallel was opened and the allied batteries brought close, it would only be a matter of hours before his defenses would be completely destroyed. On October 12, while both Cornwallis and Cochrane were viewing the allied lines, the latter was killed by artillery fire and became the only British field officer killed at Yorktown. A retreat across the York River to Gloucester had been urged on Cornwallis by some of his officers, since the expected reinforcements had not yet arrived.

Tarleton stated that sufficient boats were available to transport up to two thousand troops in one trip and that this would be enough to handle de Choisy’s inferior force of French regulars, if they tried to dispute the British retreat. Cornwallis however deferred a decision in this matter, still hoping to hold his present position until Clinton could arrive.23 The former was still gripped in a state of lassitude, unable to do anything except hold fast with fingers crossed, hoping that his luck would change.

Of the ten British redoubts and fourteen batteries at Yorktown, Redoubts Six to Ten and Batteries Ten to Fourteen directly faced and subsequently were closest to the first parallel. This particular line was manned, west to east, by about three thousand British and Hessian rank-and-file. Redoubts Nine and Ten were advance redoubts, situated three hundred yards in advance of the main line of redoubts in order to protect the British left flank.24

On the evening of October 14, the Americans had completed their second parallel to within two hundred yards of Redoubt Nine. In order to complete the parallel to the York River, it was necessary to capture Redoubts Nine and Ten from the British. The capture of Redoubt Number Nine was given to about four hundred French grenadiers and chaussers under the Count de Deux Ponts, and that of Redoubt Number Ten to the light infantry of Lafayette’s division. Both redoubts were taken successfully, with a reported allied loss of 142 killed or wounded.25

The day of the assault on the Yorktown Redoubts Nine and Ten also saw some minor action at Gloucester. De Choisy was directed by Rochambeau to make a feint toward Gloucester but the former decided to launch a real one instead. Hatchets were given to part of Weedon’s militia for them to cut down the abatis in order for the French infantry to more readily storm the redoubts. The attack was launched but half the militia lost their nerve after firing started and fled the field. De Choisy called off the attack, having lost a dozen men.26

Work to complete the second parallel at Yorktown occupied the whole of October 15. Cornwallis, recognizing that the end was almost near, ordered a sortie on the morning of October 16, in an attempt to spike some of the allied artillery brought up to the second parallel and thus delay the opening of the allied batteries in their new position. This task was assigned to Lieutenant Colonel Robert Abercrombie.27

Cornwallis ordered an attack on the two allied batteries that lay directly across from British Redoubt Number Six. Two attacking parties were formed totaling about three hundred fifty men. The move started about four o’clock in the morning. The French battery crew of about fifty men was surprised by a party of grenadiers, led by Lieutenant Colonel Gerard Lake of the guards, and fled in panic. The American battery crew, of about a hundred Virginia militiamen, attacked by a light infantry detachment, commanded by Major Thomas Armstrong, also fled. No pursuit was made, as the spiking of the guns took first importance. Unfortunately, they were only able to spike six large pieces and five small ones before a French counterattack forced them to withdraw. The whole effort turned out to be worthless, as the cannon were quickly un-spiked and put back in service. The British loss was about seven killed or wounded and five captured. The allied loss was seventeen killed or wounded.28

Cornwallis was now left with three choices: he could surrender before the cannonade started and thereby prevent any further loss of life; he could continue to hold his ground taking high losses and continue to await the promised help from Clinton, which still had not arrived from New York; or he could try to evacuate his army across the York River to Gloucester Point–a step long advocated by many of his officers.

Cornwallis decided on the last step. A messenger was sent to Tarleton at Gloucester to have his command ready to cooperate with the advance troops, to be sent over that evening to disperse de Choisy’s force of 1,750 regulars. Simcoe believed that there was a very good chance of doing this, as a spy had recently come in with information about a path that led to the rear of the French.29

Tarleton reinforced his outposts and sent several officers forward to insure no news of the forthcoming embarkation across the York River leaked out to the French and Americans. Sixteen large boats were obtained and sometime between ten and eleven o’clock at night the light infantry, the greater part of the Brigade of Guards, and that of the 23rd Regiment crossed over to Gloucester. It was estimated that three trips would be necessary to complete the embarkation. The sick and wounded were already at Gloucester, where they were earlier transported for safety to avoid the dangers of the Yorktown bombardment.30

Sometime before midnight, after part of the second embarkation had left, a violent storm came up and scattered the boats, both loaded and unloaded. It ended about 2 A.M. on October 17, with some of the boats still downstream. For reasons not entirely clear, but at least in part due to a loss of nerve, Cornwallis cancelled any further embarkation and ordered all the loaded boats still on the river to return to Yorktown. After daybreak, the scattered empty boats having returned, Cornwallis ordered their crews to bring the infantry of the first embarkation back to Yorktown. This was completed by mid-morning of October 17.31

The cannonade from the second parallel started early that morning. Cornwallis saw his works going to ruin and lacked any further means to strengthen them. He believed himself running low on artillery ammunition, and that his troops were too weak to sustain an assault. Rather than risk the loss of more lives waiting for help, which was not yet anywhere in sight, he decided to capitulate.32

Sometime about 10 A.M., on October 18, a drummer beat a parlay. A messenger was subsequently sent to propose a cessation of hostilities. General Washington agreed to the proposal. Two officers were appointed by each side to settle the terms of surrender. The guns finally fell silent for the last time in Virginia.33