A few days later, the morning stampede into the kitchen was halted by a new presence, a new sound in the air. The children slid to a standstill. The new sound came from the table, where a small box hissed and popped. Papa stood beside it, grinning. Bending over, he dialed a couple of knobs this way and that way.

Mother was adding milk to her flapjack batter. Papa twirled the dials and watched the gentle swing of her hips. A trace of a grin played about her face too. Her body was turned away from the noise and action around the table. Papa released the knobs.

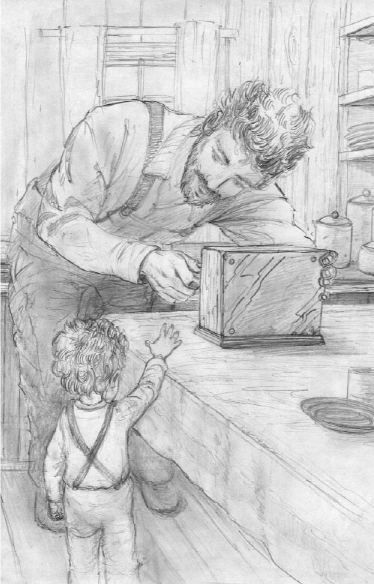

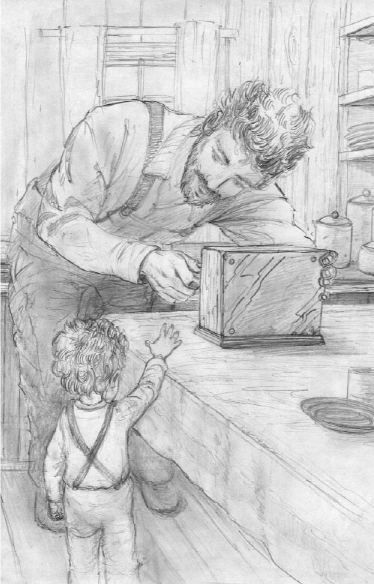

Closest to the box was Joseph. He reached a pudgy hand up to one of the knobs. Quick as a hen striking a seed, Papa slapped the hand away. Joseph drew back his hand with equal speed. Rubbing his knuckles absently, he said, “But why, Papa? What is it?”

“This is not a toy for you children to play with.” Papa looked at each of them in turn, wagging his finger sternly.

“Isn’t that the truth?” said Mother. “This is your father’s toy. Make sure you let him play with it.” She looked out the window, which was clear, and went back to work with her wooden spoon.

“That’s right,” he said, nodding. “It’s my toy. Mine. Get it?” But then Papa grinned. He never could remain stern for long.

A strange crackling sound kept leaking from the box. Papa fiddled with a dial. More noises came in, faded away, came back. The noises became a man’s voice: “…walked up to me while I was speaking with my friend, Bill Aberhart, and this man says to me, ‘Preacher, God is my field, all blown away. Everyone knows that but you.’ But do you know that, radio friend? How can you blow away God?” The voice sputtered, faded out.

“Goldarn signal anyway.” Papa turned the dials.

Then another voice: “And this just in. General Motors has capitulated to worker demands and recognized the United Auto Workers’ union. This has occurred after a forty-four-day occupation of GM factories involving violent clashes between police and strikers, and the stationing of machine-gun nests in Flint, Michigan streets by the National Guard.”

“Wash up and get ready to eat,” Mother said.

Sighing, Papa spun the left knob till it clicked. The crackling stopped, and the unknown voices left the kitchen, leaving them all in a stunned silence.

Mary had been holding Jessy up to let her see Papa’s new toy, and he looked the doll full in her dirty face. “Well, Jessy,” he said with a smirk, “you’ve come into quite a world. The people are either being gunned down to save a few measly bucks on wages, or they’re pleading with heaven to end all their troubles. Both great solutions, let me tell you.”

“Raynold,” said Mother, pouring warm water into a basin, “don’t infect the children.”

“The day our troubles end is the day this here doll wakes up and helps out with chores.” Papa looked at Mary more fiercely than she was used to. “I mean really helps out, not just pretend.”

Were they planning to fight again? Mary hoped not. Papa tapped the box, drumming his big blunt fingertips on it. The hissing sound started again. The children studied the noisy box intently. What would it say now?

Papa laughed. “That’s Mother’s pan, not the radio, you silly kittens!”

Sure enough, a spoonful of batter had dropped into the hot grease of the frying pan. The children smiled at him sheepishly.

“You weren’t always such a cynic,” Mother said wearily. More than a tinge of sadness showed in the slump of her shoulders.

Papa washed and dried his hands and sat down. He rubbed his eyes with his palms, and Mary studied the very large veins in his square hands. “At least I’m not doing myself in, am I, like some have.” He grabbed the pitcher and poured milk into all the children’s glasses. Judith scowled because she usually poured her own. “There’s a thing, now. A drought always gets you a good crop of suicides, at least.”

“Maybe we haven’t lost as much as them.”

“No, but maybe we haven’t kept enough to get by neither. Six, seven years ago we made five hundred dollars a year. Less than a hundred now. I hate to think how much less.”

“The times will turn.” Mother’s words were firm, but her voice had that tone again that Mary hadn’t heard since Christmas. “Until then, we’ve got the eggs and milk to keep us afloat.”

“Not at sixty cents to the bushel. And not if we don’t get a crop. No, Ruthie, times won’t turn!” Papa still held up the jug, oblivious to this weight that Mary could hardly lift.

Those big veins in Papa’s arms and hands looked like the wrought-iron steps of the old buggy. Mary knew by experience that they were hard too. Why did his hands look like tree roots and Mother’s stay slender, although red and chapped? Was outside work so hard that it turned a man’s hands to roots? She studied Joseph’s baby arms and hands. Had Papa’s arms ever been so smooth? The next time they saw Johnson, she decided, she would check to see if his hands were hard as roots too, or if it was just Papa.

Before long, Mother set the first steaming flapjacks on the table. “Well, look at this: We can feed ourselves. We’re not on Relief like some of our neighbors. That’s something, isn’t it?”

Every few weeks, usually when he’d seen a public notice that potatoes could be picked up at such and such a place, Papa would flutter and shake his out-of-date newspaper and swear he’d never take Relief. A government handout wasn’t something to be ashamed of, he said, but it wouldn’t chase away your troubles either. Now he frowned, forked a flapjack onto his plate, added a dollop of butter and, looking down at his plate, said, “I’m thinking of joining the CCF. They’ll get us a decent market. Then we’ll only have to worry about getting us a crop to sell.”

“Mary, don’t play with your food,” Mother said.

Mary stopped burbling her milk. “What’s a CCF?” she asked as white bubbles popped all the way from her lip to her nose.

Papa gazed at his plate, deep in thought. “And don’t go telling me what I used to say about running with lemmings, neither,” he said finally. “Us in a good market— that’s all I care about.”

“I’ll run with lemons, Papa,” Joseph said eagerly.

“Lemmings, not lemons. And if you do, you’ll have to jump off a cliff.”

“Maybe I’ll just stay here then.” Joseph shoved a finger into a flapjack.

“Cooperative Commonwealth Federation,” Judith announced. She turned toward Mother as if awaiting some reward for this tardy information.

“Whatever makes you happy,” said Mother, seating herself. “Judith, grace.”

“God is great, God is good. Let us thank him for our food.”

Except for Joseph smacking his lips, they ate their meal in silence. Judith had said the right words, Mary was sure. The food was good. Nobody had done the least bit of wrong. There did not seem to be any reason for such silence.

After breakfast all three children went out to the barn to watch their father muck out the pigsty. It was a muddy Saturday, and warm. Mary allowed Jessy to come but held onto her tight. They were playing in a sunny protected spot between the open barn doors when Papa came out, pushing the wheelbarrow. He set it down, leaned against a big doorpost, breathed deeply and shoved his hands in behind the bib of his overalls.

“See, Jessy?” Mary ran her fingers along the bulging veins on Papa’s forearms. She felt Jessy’s smooth arms. “Isn’t it a lovely day, Papa?”

“Sure is, sweetheart,” he said. “Though I think by the looks of that sky, we’re about done with this lovely spell.”

“And we need that snow back quick, right, Papa?” Judith asked. Copying his actions, she leaned on the door. She raised up her face to gape at him.

“Yup. Sure do.” He scoured the sky overhead.

“Why’s that sky so yellow?” Mary asked. Not that it was so very yellow this morning, but Mary wanted to hear her father talk. Despite his anger at the drought, Papa liked to tell her about the prairie turning to dust and rising over itself like a great yellow ghost. When he described drying sloughs and creeks and the homeless waterfowl and the parched land broken by huge cracks and the hot windblown dirt collecting in summer drifts behind every fence-post and rock, Mary saw it all more clearly than she ever did in real life. Now, with all this wet mud around them, Papa might tell her the story of dry dirt, which was jailed in ice every winter, then released in spring to drift and wiggle and creep toward the house with one intention: to foil Mother’s best housekeeping efforts.

But Papa only sighed. “You been told why your whole life, young lady.”

“I forgot.”

“How I wish you could see an honest-to-goodness blue sky for once.”

Mary looked over at Judith, whose eager face was drooping. Her eyes were falling away from Papa’s uplifted face. Worse, Judith had the beginnings of that look. She’d be in a monster mood tonight. And Mary had done nothing to deserve it.

“Train!” Joseph called. A faint moan came down from the western edge of their shallow valley. Only Joseph paid attention to it.

“Why aren’t you happy, Papa?” asked Mary. “Is it the Depression?” She’d heard this word often. Usually given by Mother as the reason for people’s misfortunes, it was an all-purpose word, good for anything from blights of grasshoppers to moments of sadness.

Papa glanced down at her and said, “I’m not sure you’d understand.” He looked up at the sky and smiled sadly. “When Judith was born…”

Judith jerked her head up.

He watched a raven flap across the sky. “Well, things looked not so bad back then. But we already lost our first baby. I mean, Mother made an angel, and we lost her. This is hard to describe to someone like you. You’ve never been betrayed, Meadow Muffin. The next year was the year before the big crash, and Judith was born. Anybody with open eyes could see that things had to go sour, not that I saw. You were born out here. Opa died and we buried him in town. We lost our savings on October 29. Then we found out about the hole in your heart. There seemed to be no end to what a man could lose, and that was just the beginning.”

“I know what a crash is,” Judith said. The small knowing grin on her face told Mary this would be a joke of some kind, or a trick.

Mary didn’t know. She suspected, though, that crash and depression had practically the same meaning. But she wasn’t going to ask and give Judith any satisfaction.

Joseph swung on the handle of the heavily loaded wheelbarrow. He had a single intention: to tip the wheelbarrow and spill the pig manure, which reeked and dripped through the plank sides. Judith, done waiting for anyone to ask her what a crash might be, kicked at the barn door. When Papa remained lost in his reflections, she ran out into the yard to stand by the iron pump at the well.

Papa thought for a moment, then fingered his knee, where the patch was coming loose. “Then I got me a hole in my heart too, somehow, and lost what little faith I had. Watch out, son!” The wheelbarrow was ready to spill as its legs sank into the soft soil. “Can’t you leave that manure alone? Go help Judith, will you?” Papa pulled Joseph off the handle, shook his head sternly and moved the dripping reeking mess to solid ground. Leaning against the doorpost again, he added, “A crash, by the way, is what we’re living here. When you lose your shirt, and nobody’s interested because they lost theirs too.”

“Will we crash again, Papa?” Mary asked.

“Can’t say.” He scanned the yard till his eyes rested on Judith. “I guess we ought to get ourselves uncrashed first.”

Judith was filling a pail with water, pumping at a pump handle as high as her head. Its metallic squealing filled the yard.

“It ain’t right,” whispered Papa, “but every time I look at her I see a parade of all the things I lost.” He spoke as if he were telling Mary a secret, and a thrill ran through her at his new, confidential tone.

Releasing the handle, Judith turned to the right. She raised her arm. With her palm up and fingers extended, she might have been summoning someone nobody else could see.