Midsummer, the Sun,

and the Fairy Folk

The summer solstice is a truly magickal occasion. It’s a celebration of the year’s shortest night and the power of the Sun. Over the centuries it has been associated with the Fey (fairy folk) and epic battles between the Oak and Holly Kings. It might also be the original magickal holiday, with some of those magickal traditions being passed down for millennia.

One of the oldest representations of the Sun is the solar wheel, a perfect circle with two intercrossing lines running through its center. Solar wheels appeared in a variety of different ways in ancient art. Most often they served as the wheels of chariots driven by solar deities, but they also sometimes appeared on the decks of ships when a boat was used to illustrate how the Sun made its daily journey through the sky.

What’s most interesting about the solar wheel is just how long it’s been venerated in summer solstice celebrations. In the 1400s written accounts of people lighting wheels on fire and rolling them down hills on the summer solstice began to show up in Northern Europe and Great Britain, but the practice is probably much older. Accounts of flaming wheels have been a part of the historical record since the fourth century CE and seem to be an ancient pagan tradition.

A good harvest was thought to be assured if the flaming solar wheel made it down the hill without toppling over. To ensure the wheel actually made it down the hill a long pole was inserted into its center with two people then holding each end and running with the wheel as it went down the hill. But that wasn’t the only time fire was a part of Midsummer celebrations.

Ancient pagans believed that fire could be used for both purification and protection, and both of those ideas were incorporated into how fire was used on the summer solstice. To drive out negativity, bad spirits, and to ensure a bountiful harvest, people would run through their fields of crops with lit torches, the fire and smoke doing the heavy magickal lifting. Bonfires were a part of Midsummer celebrations, too, and were used to chase bad spirits and fairies away. The bonfire as a way of celebrating the solstice lasted well into modern times as well, though today they are often lit by Christians on the Feast of Saint John.

These ancient practices can be easily adapted for use in modern solstice celebrations. Lighting a “bonfire” in a grill or portable fire pit (and if you live in a spot where you can light a real bonfire, all the better!) is an easy way to practice a little ancient magick. Simply throw whatever you’d like to get rid of in your life into the fire and ask your favorite solar deity for assistance in manifesting that change. If what you want to get rid of can’t be easily represented by a physical item, simply write whatever it is down on a piece of paper and burn that.

Like pagans of old, I like to use Midsummer for cleansing, though I often cleanse my house instead of crops. As the Sun sets on the year’s shortest night, I light up a big bundle of sage and use the smudge smoke to purify the biggest problem areas of my home. Some of those problem areas are mundane (my television makes me lazy) and some are a bit more magickal. My ritual room tends to attract spectral “visitors.” Many of them are unwelcome, and a little purifying smudge will generally get rid of them.

My wife won’t let me run with any flaming solar wheels, but I’ve thrown paper ones into our Midsummer fires over the years while asking for a productive year. An alternative idea is to bake a loaf of bread in the shape of a solar wheel. While eating the “solar bread,” think of the Sun’s power entering your body and powering you through the next six months. Solar loafs also make nice offerings, and I always share a little bit with the Goddess and God and the fairy folk who live in my backyard.

The Fey

The Fey have long been associated with Midsummer, and in both a positive and a negative way. Until relatively recently the fairy folk were seen as a “bad presence,” and fires were lit on the summer solstice to keep them away from people and crops. As time passed the Fey were increasingly seen in a positive light, and while their presence wasn’t always requested, they came to be associated with Midsummer celebrations. Much of that association is probably due to Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream (which dates back to the 1590s).

There are some disagreements on just who or what the fairy folk are. Some people see them as an ethereal race of beings existing parallel to humankind. Others see them as “nature spirits,” but no matter how you perceive them, Midsummer is a great opportunity to interact with them and pay them homage. The Fey are said to live anywhere there is a bit of nature—for most of us that probably means our backyards or a local park—and they usually exist in secluded spots. In my backyard they occupy a space between our fence and lemon tree. Figuring out where the Fey call home in any specific place is a matter of belief and intuition. They aren’t going to tell you where they are: you just have to trust your instincts.

At Midsummer my Witch coven often leaves them small shiny gifts; glass beads seem to be a favorite. They also like sweets, so instead of ritual bread, we generally have ritual cupcakes on the summer solstice. Alcoholic libations, especially wine, are another good choice. Midsummer is also a good night to present them with even more substantial gifts, such as a fairy house. (You can either make your own or buy a small wooden dollhouse at an arts and crafts store.)

We also sometimes ask for their assistance near Midsummer. On the night before the sabbat we leave small trinkets outside next to their spot in our yard and ask for their blessings upon them. If you choose to ask the fairy folk for a favor be sure to leave them a small gift. While it’s unlikely that they are going to destroy this year’s harvest, they can be mischievous and even a bit spiteful. It’s always best to say thank you just in case.

The Sun: A Companion in Magic

Most modern books about magick spend a great deal of time on Moon magick. Such tomes will tell you that if you are putting a spell together for gain you should wait until the Moon is waxing (getting bigger) in the sky. For operations such as getting rid of a bad habit they advise to wait until the Moon is waning to begin your spellwork. The Moon is a mighty companion in magick, so I understand the emphasis, but the Sun is just as strong. It’s just a little bit different.

The power of the Moon is subtle. Over the course of twenty-eight days its light gradually grows and shrinks in the sky. This cycle is then repeated about eleven more times a year. The Sun is something else entirely and has two distinct stages.

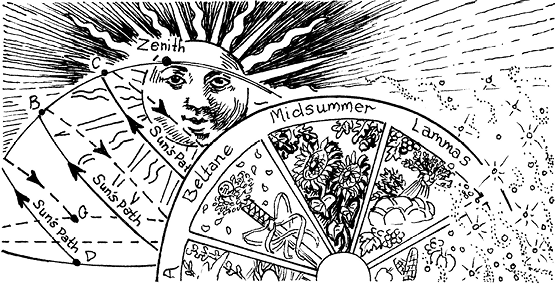

Most Pagans and Witches are conscious of the bigger stage. We call it the Wheel of the Year, and it’s the yearly cycle of the seasons and, by extension, the Sun’s waxing and waning energy. Yule (the winter solstice, about December 21) marks the shortest day, but also the point from which all days begin to increase in length over the solar year. Midsummer is the longest day of the solar year and begins the shortening of days until Yule rolls around again.

Many Witches and Pagans use holidays such as Ostara (the spring equinox, about March 20) as a time to bring things into their lives. As the world grows in light, warmth, and greenery, they tap into those energies so that they might manifest in their own lives. To use a cooking analogy, using the cycles of Sun in magical work for gain or to be rid of something is a lot like using a slow-cooker or simmering a soup: the results are generally extraordinary but not so great if you really hungry now. Sometimes we don’t have time to wait, which is when the Sun’s second cycle comes in handy.

The Sun’s daily rise and fall is an often overlooked tool in magickal practice and is easy to work with. From sunrise until solar noon is a time of gain, ideal for money magick or trying to bring new things into your life. For example, when I’m trying to stretch the dollars in my wallet, I leave my billfold in a sunny spot in the bedroom to tap into the Sun’s “growing” energy. The hours directly before and after solar noon feature the Sun at its strongest and most intense; when the magick needs to be especially powerful, this is the time to work. Afternoon and until sunset are the best time for getting rid of things

My wife and I were once hexed by a bad Witch in our area (they don’t all follow the Wiccan Rede) and needed to take some quick action. I didn’t have time to wait for a waning Moon or even for the Sun to set (we had both had a pretty rotten day). Instead I took an ice cube out of our freezer, held it between my hands, and chanted the name of our local bad Witch along with the words “go away.” When my hands couldn’t stand the cold anymore I threw the ice-cube out into our yard and asked the earth and the Sun to take her bad energy away from us. As the Sun set the bad magick decreased, and as the ice melted that energy was absorbed into the ground.

Sunset is an especially powerful time for magick, and those evenings when the Sun is chasing the Moon are perfect for love spells. Sunset is also a liminal time, existing between the two extremes of night and day. I find it an especially appropriate time for communing with my deities (both in and out of ritual space) and for reaching out to the Summerlands (the world of the dead).

The Sun is often associated with male deities and masculine energies in magickal circles today, but that wasn’t always the case. History contains just as many Sun goddesses as it does Sun gods, which means the energy of the Sun is capable of serving a variety of purposes. No matter your intent or working, the power of the Sun is capable of producing some truly magickal moments.