The written origins of Daoism are to be found in a book which was originally entitled Laozi but later called the Dao-de Jing. The title Laozi was long understood to be the name of its compiler, but from the historical sources it is impossible to identify any individual who corresponds to the Laozi of the book. Even the usually well-informed Si-ma Qian, who wrote the definitive history of China, the Shiji, published in 90 BCE, admitted in his biography of Laozi that it was impossible to know what was the truth.

It is perhaps significant that the literal translation of Laozi is ‘old master’, and there is some evidence that a number of books written at around the same time as the Laozi had similar titles, imputing the wisdom of age to their content. On this basis we can say that there probably never was a person called Laozi who wrote the work of that name, but in the China of 300 BCE the mere existence of a book with that title would have carried the presumption that it had indeed been written by such an individual. The total absence of any trace of ‘Laozi’ himself puts him into the realm of the legendary sages, but in Daoist tradition his alleged date of birth positions him as a predecessor of Confucius – an assertion which was probably not accidental, despite the fact that most of the extant works of Daoism are later than the time of Confucius.

Despite the uncertainty around the actual person of Laozi, the content of the book that carries the name is clearly consistent with the nature-based philosophy and occultism that had come down through the Western Zhou (c. 1100–770 BCE) and Spring and Autumn (c. 722-481 BCE) periods. It does, however, mark a shift from the earlier occult schools towards a mysticism that would characterise the formal Daoist school.

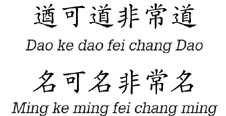

This formal Daoism takes its name from the character dao, meaning a way or path. It was the belief of the Daoists that there is a path or ‘grain’ of nature that the followers of Daoism should strive to follow. The Dao itself was seen as mysterious and unknowable; indeed, the very first couplet of the Dao-de Jing is:

The character ming at the beginning of the second line of the couplet means ‘a name’, and the couplet can be translated into English as:

A Way which can be defined as ‘Way’ is not the changeless Way.

A name which can be defined as the name [of the Way] is not the name of the changeless.

So the starting point of the Dao-de Jing, which is the master document for all subsequent Daoist thinking, is that the fundamental way of nature is unknowable and un-nameable.

Another concept basic to Daoist philosophy is the concept of non-action, or wu-wei. The classic statement is in Section 37 of the Dao-de Jing, which begins:

The Dao is always without action,

yet there is nothing which is not done.

This is telling us that the world’s ‘grain’ of Dao is self-sufficient for the world to function, and that there is no need for specific activity on the part of Dao.

The book then goes on in its next section to point out that non-action should also be characteristic of human beings:

One of superior virtue practices inaction, and there is nothing left to do;

One of inferior virtue acts on something, and things remain to be done.

Some light may be shed on the concept of wu-wei by another section of the Dao-de Jing, where the point at issue appears to be the problems which can arise from over-exertion:

One who stands on tiptoe has no stability,

One who strides out does not progress steadily,

One who is self-centred will not make a good impression,

One who is self-righteous will not be respected,

One who is self-aggrandising achieves no success,

One who exaggerates his qualities will not endure.

From the standpoint of Dao one can say ‘Excess food and accumulated baggage are to be abhorred’,

So the followers of Dao do not associate with such things.

The actions that are criticised in this passage exemplify self-defeating attempts to achieve some result. The first two are simple to understand, but they set the scene for the following examples, which are concerned with excesses of personal behaviour that are aimed to impress the onlooker but, because they set up an overblown reputation, will in the end fail as the true nature of the person becomes clear. All these attitudes are seen as failure to follow the Dao of how things are. Coupled with the previously quoted section, we can see how wu-wei, non-action, becomes a concept that involves not pushing against what is – the undesirable action is that which would attempt to work against or across the natural Dao of things.

A different take on the quality of ‘absence’ implicit in wu-wei is to be found in Section 11 of the Dao-de Jing:

Thirty spokes may converge on the wheel’s hub,

But it is the space in the centre which connects to the cart.

A lump of clay becomes a vessel,

But it is the space in the centre which makes it a vessel.

Construct doors and windows for a room,

But it is the apertures which make them useful.

So consider what is in order to see the gain,

And consider what is not, to see its utility!

As we shall see from examples in the next chapter on Zhuangzi, the author of the Dao-de Jing is saying here that the spaces, whether in the centre of the hub, within the pot, or left for the windows and door, are not made by the artisan, and are therefore in accordance with Dao. The artisan is only making his structures ‘conform’ to the Dao, which is what gives the physical objects their utility.

It is easy to over-simplify this form of Daoism as back-to-nature escapism, but that would fail to do it justice. It is perhaps more an expressed form of opposition to the other ongoing strand of hierarchical thought, where life became highly formalised and relied upon such concepts as adherence to formal rites. These rites are reflected in the continuing production during the Western Zhou period of ritual vessels for offering food and drink to the ancestors or altars such as those to the earth or to the crops. To judge by the Dao-de Jing, the social structures and relationships of the administrators were anathema to Daoist thought, as shown by such sections as the highly ironic Section 18:

When the great Dao is lost,

Humaneness and Righteousness arise;

When wisdom and intelligence emerge,

The result is hypocrisy.

When the six family relationships are forgotten,

The result is filial piety;

When the state is confused and chaotic

Loyal ministers emerge.

As we shall see, Humaneness and Righteousness are fundamental virtues according to the tenets of Confucius, and filial piety and loyalty to one’s superior in the hierarchy are also values that are an integral part of the Confucian theory. So, in Section 18, the writer is mocking these formal aspects of life, pointing out that such codified values are far inferior to the natural grain of things, which, if followed, will effortlessly bring good outcomes to those who follow it.

To summarise, we can say that the philosophy contained in the book Laozi is one in which all one’s thoughts and actions should be carried out in conformity with the natural order of the world, contained within the concept of Dao, and that all action that would subvert this Dao will ultimately be ineffective. As far as the person Laozi is concerned, we cannot even be sure that he ever existed, but as we shall see in the next chapter, later Daoist texts provide plenty of anecdotes about him.