It was not until the very late nineteenth century that Chinese scholars began to study Western philosophers. For example, Yen Fu, who had been sent to England to study naval science, read the works of many English philosophers, including Huxley, Smith and Mill, and translated them into Chinese. After the Sino–Japanese war (1894–95) his translations were widely read in China by those who believed the country could be transformed by Western thought. He also translated Montesquieu’s Esprit des Lois, and Wang Guowei, a historian of philosophy, translated Schopenhauer and Kant.

In the early twentieth century, Beijing University taught philosophy, and in 1915 a proposal emerged to open a Department of Western Philosophy, but the death of the Professor brought this to a premature end.

Of the Western philosophy of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, only Logic became an integral part of Chinese philosophical thought, through a seventeenth-century translation (by Li Zhizao in collaboration with Jesuits in Beijing) of a medieval work on Aristotelian logic, which appealed to the Chinese because of superficial resonances with the essays of Gong-sun Long.

The early years of the twentieth century saw a great interest in Western philosophical and political thought among the growing number of Chinese who were working and studying in Europe. They were to have two key impacts on the intellectual life of China. First, they became more familiar with Western ideas, particularly those of Marx and Engels. Secondly, and more immediately, there were Chinese in France at the time of the making of the Treaty of Versailles in 1919 that defined the settlement after the First World War. After initial neutrality, the Chinese had entered the war after attacks by Japan, and it was hoped that the Versailles treaty would return foreign-held Chinese territory that Japan had seized. In the event, Japan got the right to dispose of the German-held area of Shandong, and the Chinese delegates to the Versailles conference refused to sign. This news, telegraphed to Beijing, aroused great anger, and on 4 May the students of Beijing University demonstrated against the Treaty. They identified one of the greatest obstacles to Chinese progress as the archaic written form, known to the West as ‘Classical Chinese’, which was largely unchanged from the Zhou Dynasty, and did not directly reflect the spoken language. An unsuccessful attempt had been made in 1907 to represent the vernacular in written Chinese, and one of the students’ key demands was for the replacement of Classical Chinese by a written form, known as ‘baihua’, based on speech, which could be understood more easily by non-scholars. This time, reform succeeded, and so another link to the classical Confucian past was broken.

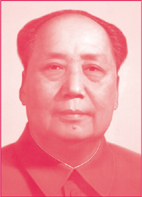

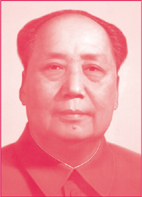

The arrival of Marxism in China was to have a major influence on Chinese affairs for the remainder of the twentieth century and beyond, and the May Fourth Movement provided a fertile bed for ideas of revolution based on popular discontent. By 1919 Marxist study groups existed in many Chinese cities. Gregor Voitinsky, a member of the Soviet Comintern, set up the first Communist Party branch in Shanghai in 1921. Marxism-Leninism rapidly became the main ideology of the disaffected population, and following the collapse of Confucianism at the end of the Empire and the repressive actions of the warlords of the Republican era, it became the dominant philosophy. The history of Communism in China under Mao Zedong is well known, and by 1949 the Communists had assumed power in China.

One of the key targets of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) was that of traditional Chinese culture. For example, Classical Chinese documents had been a specialist field since 1919, but in the 1950s the Minister of Culture, Guo Moruo, introduced a simplification of the Chinese script, hoping to make Classical literature even more remote than the baihua reform had done. The effect was illustrated when the author visited Xi Bei University in Xi’an in the 1980s and started to read an eleventh-century copy of the Shiji on display in the library. The librarian expressed surprise, as he himself was unable to read it.

Under Mao, study of the Classics was discouraged and mass literature was Marxist-Leninist polemic seen through the lens of the CCP. Rigid Party control was established over the whole country. For forty years traditional philosophy and history were discarded, except for examples of proletarian courage and insight to support the Marxist-Leninist-Maoist line. Even technology and industry had to comply, the slogan ‘better Red than expert’ underpinning such disasters as Mao’s ‘Great Leap Forward’ and ‘Great Revolution of Proletarian Culture’ in the 1970s and ’80s. The only indigenous Chinese philosophy reflected in the period of Mao’s leadership of the CCP was Legalism. Rules abounded, punishments could be draconian, and the neighbourhood groups whose members were expected to inform on each other were an echo of the fourth-century BCE policies of Shang Yang.

After Mao died, ‘The Gang of Four’, including Mao’s wife, who had masterminded the activities of the ‘Red Guards’ during the Cultural Revolution, soon fell. From then on, Mao’s Communism was softened, to take account of the changing economic and political climate of China and the wider world. The CCP, however, maintained its grip on the state and its citizens.