LEE Kuan Yew was born at 92, Kampong Java Road, Singapore, on 16 September, 1923. His family have lived in Singapore for more than a hundred years and come from the Hakkas, a northern Chinese tribe of tough wanderers.

Lee Kuan Yew is an intellectual. He looks like an intellectual. He speaks like a scholar. His command of English is unusual. He is a quick thinker. At Cambridge he took a double first in Law, and in the final examination was placed first in the honours list, winning a star for special distinction. A British diplomat once described Lee as “the most brilliant man around, albeit just a bit of a thug”, a judgment considered fair enough in a political arena where an ability to meet opponents on their terms is an essential part of the successful politician’s make-up. “We are playing for keeps,” Lee Kuan Yew warned the militant communists. He defeated them in democratically held elections, and in a referendum. Today, most of Lee’s political enemies have either retired from politics or are in goal. In the 1968 elections fifty-one of the fifty-eight PAP candidates for an enlarged Parliament were returned unopposed. Early in 1970 five members of parliament retired. In the subsequent by-elections, in April, the newly formed United National Front contested two seats, the PAP all five. Three of the PAP candidates were returned unopposed: the other two were returned with substantial majorities.

Five feet ten and a half inches tall, Lee Kuan Yew weighs 160 pounds. He watches his weight carefully. He rarely eats rice or bread, seldom drinks beer. He walks with a slight swagger, his shoulders thrown forward a little as each foot comes down. This may seem to indicate Lee Kuan Yew’s confidence or natural aggressiveness. More likely it is due to the fact that he has rather tender feet.

In his personal habits, Lee is inclined to be finicky. His hands are always scrupulously clean, his nails neatly cut and filed. He is incapable of doing anything slovenly or carelessly, whether it is putting on a highly polished shoe, or reaching an important decision. There is no room on his large desk for anything other than the letter to be signed or the file to be read.

Like President Kennedy, whom Lee admired, Lee Kuan Yew seldom reads for distraction. Like Kennedy, he does not want to waste a single second. Every moment of his life he seeks to invest, not spend. Aloof in manner, he is slow to make friends. He is suspicious of the hail-fellow-well-met approach. Lee’s sense of humour, developing with age, is not always kind. He suffers fools not at all, but he rarely prejudges anyone. Upon first encounter all are met on terms of equality. An exchange of a few sentences, however, is often sufficient for Lee’s decion: either the person reacts intelligently or he does not, and this judgment will apply to prime minister and dock-worker, don or road-sweeper.

Lee is a combined Left-wing demagogue and emphatic realist. Some things are possible. Others are not. He believes deeply in democratic methods, and his philosophy is built around the sanctity of law and the free will of the people: but there are times when he is reluctantly forced to take strict, even non-democratic measures against a minority of thugs, secret-society gangsters and political opportunists—those who have placed themselves outside the rules—in order that he shall preserve the greatest good for the community as a whole. Lee never forgets that Singapore is in Asia, where Western concepts of democracy have yet to be understood by the masses and accepted as a way of life.

Lee is attractive to women. His face is rugged, and slightly pocked. His thick black hair, which has no parting, is streaked with grey. When he smiles and laughs his personality is changed completely. These are the moments of relaxation. His normal expression is a mixture of intense concentration and aggressiveness. Lee is not an ivory-tower intellectual and is inclined to be critical of them (“It is amazing the number of highly intelligent persons in the world who make no contribution at all to the well-being of their fellow countrymen”), for he is by nature and by reasoning an attacker of problems, not a student of the abstract.

Lee Kuan Yew is the eldest son of Lee Chin Koon, a retired employee of the Shell Company. Lee’s father now works in a shop in the High Street, where he sells watches and jewellery. His mother, Chua Jim Neo, is famed in the state as an expert teacher of cooking in the Chinese and Malay styles. She was 16 when he was born. His father was 20. Lee Kuan Yew married Kwa Geok Choo on 30 September, 1950. In his year, Lee Kuan Yew was the most brilliant of all scholars in Singapore. He won a prize which entitled him to a scholarship at Raffles College. The war had begun in Europe, and his plans to go to an English university had to be postponed, and so he accepted his prize and put in two years at Raffles College. “And there two things happened which have since stood me in very good stead. I met my future wife, and I got a grounding in economics.”

Kwa Geok Choo, Lee Kuan Yew’s wife, was the most brilliant girl scholar of her year. Educated at the Methodist Girls’ School (she is not a Christian) she was first in the Senior Cambridge Examination for the whole of Malaya. At Raffles College, Miss Kwa graduated in 1947 and was awarded a Queen’s Scholarship. Then she went to Cambridge where she became the first Malayan woman to be awarded first class honours, which she obtained after only two years of study.

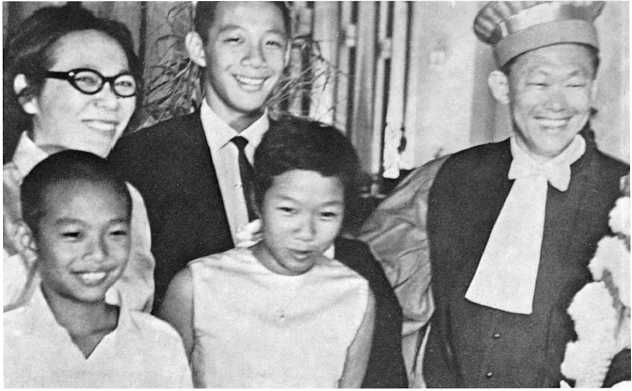

The Lees have three children, two boys and a daughter. Lee Hsien Loong was born in 1952; Lee Wei Ling, the daughter, in 1955, and Lee Hsien Yang in 1957. Lee Kuan Yew is a very happily married man. With his wife, who is head of the legal firm of Lee and Lee, he is an active participant in the joys and troubles of his children’s growing up. Hsien Loong showed early signs of following in the footsteps of his gifted parents: by the time he was fourteen he could read, write and speak Russian, English, Malay and Mandarin with ease and fluency, and his interests range from playing the clarinet to nuclear physics.

Lee Kuan Yew is a socialist. To Lee socialism means social justice, better living, freedom and peace. Lee argues that, holding these principles, socialists must work out the best way of bringing all this about in their own countries. He is essentially an idealist, yet a practical and ruthless idealist. “You start off with idealism, you should end up in maturity with a great deal of sophistication giving a gloss to that idealism,” he told a youth gathering in Singapore in 1967. Lee is a hard worker and a disciplinarian. Most days, with a teacher, he polishes his Mandarin and his Malay, for it is of vital importance in a multiracial nation that the leader should be able to communicate directly with as many of the people as possible, and more people in Singapore speak Malay and Chinese than English.

Lee Kuan Yew is also a firm believer in the importance of keeping fit. Every morning he does exercises, which include press-ups, skipping, and arm exercises with small weights. He has a very light breakfast, sips China tea throughout the day, and makes dinner, also never heavy, his main meal. He enjoys a glass or two of wine in the evening.

Lee Kuan Yew is probably the best golfing Prime Minister in the world. He took up the game while studying in Cambridge, where he discovered that golf could provide him with regular exercise all the year round whilst clad in sweater and gloves—essential clothing most of the time in England for a man born in the tropics. He is Prime Minister of the independent sovereign Republic of Singapore, the newest and smallest state in Asia. He first became Prime Minister in 1959, when he was 35.

Strategically placed geographically, just north of the Equator, where the waters of the South China Sea meet the Indian Ocean, at the southern tip of the Malayan Peninsula, a stone’s throw from Indonesia, about half way between China and Australia and New Zealand, a few jet hours from Japan and India, the Republic of Singapore is a flat tropical island of some 224 square miles, a third the size of Greater London. Here live in harmony a multiracial population of two million industrious people, most of them of Chinese descent. They enjoy one of the highest standards of living in the East. The Chinese have been in Singapore a long time. They were there hundreds of years before Raffles came. Singapore in the fourteenth century was known as Tumasik, and in a report written in 1349, Wang Ta-yuan, a Chinese merchant adventurer, gave the impression that a fairly large settlement of Chinese was already living on the island.

With an internationally famous free port, the fourth busiest in the world, and an equally renowned airport capable of accommodating and servicing the largest and fastest aircraft, Singapore, at least until the end of 1971, will continue to provide accommodation for Britain’s military, air and naval presence East of Suez. In 1968, Mr Harold Wilson’s Government unexpectedly decided to withdraw all British forces from Singapore by 1971, and, at the end of 1968, the naval base, which cost the British millions of pounds to build, was handed over as a gift to the Singapore Government for conversion into a commercial undertaking, “a practical illustration”, as Singapore’s Foreign Minister remarked at the handing-over ceremony, “of successful decolonization”. Politically, Singapore is neutral, but the People’s Action Party Government, led by Lee Kuan Yew, insists upon the right inherent in all independent sovereign states that Singapore shall make its own defence arrangements. Early in 1971 the British prepared to withdraw their bases. Talks were then proceeding for a five power defence arrangement between Singapore, Malaysia, Britian, New Zealand and Australia. Singapore has a well-trained police force and efficient armed forces, including patrol ships and fighter aircraft. National Service was introduced in 1967.

Just over a hundred and fifty years ago, when Sir Stamford Raffles of the East India Company was rowed up the muddy creek, in search of a suitable place in which to establish a British trading post, he found Singapore an island of marshy swamps, scrub and thick forest. On the coastal fringe a few Malay fishermen lived in primitive huts, and inland were settled a handful of Chinese gambier growers.

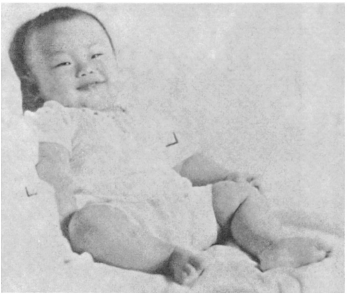

Lee when an infant

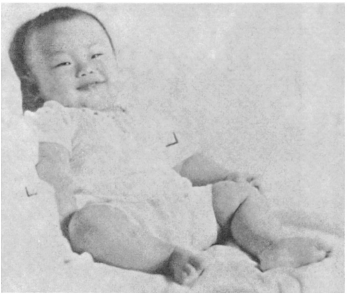

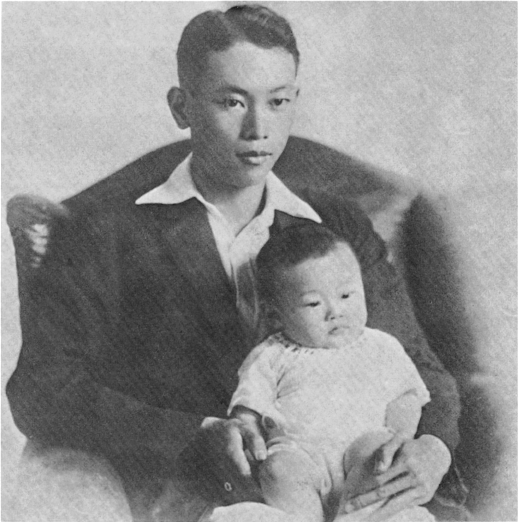

One-year-old Lee Kuan Yew in the arms of his father, then twenty

Young Lee in Chinese dress on a festive occasion

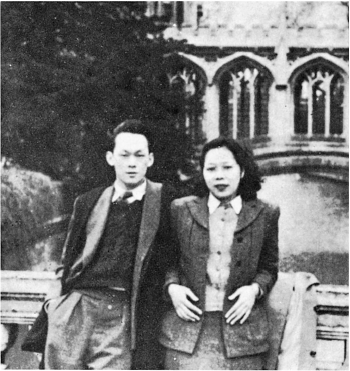

Undergraduates at Cambridge, 1946

Cutting the wedding cake in 1950

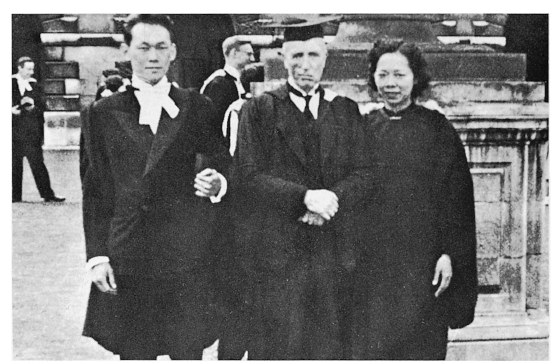

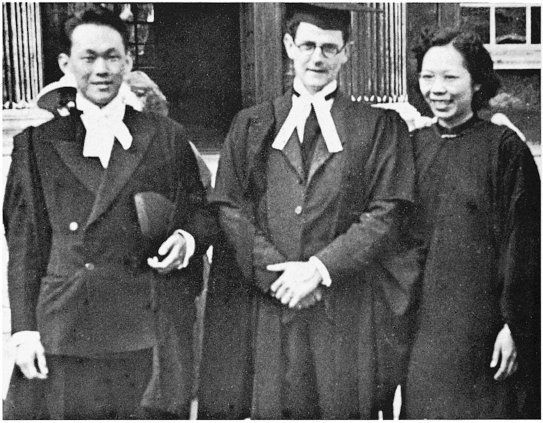

At Cambridge in June 1949. Mr and Mrs Lee Kuan Yew with Lee’s Censor and friend, W. S. Thatcher

At Cambridge in 1949. Lee Kuan Yew with Trevor C. Thomas (now Vice-Chancellor of the University of Liverpool) and Kwa Geok Choo (Mrs Lee Kuan Yew)

The Lee family in 1967 in Cambodia, after the Prime Minister had received an honorary doctorate of law from the Royal University. (Back —Mrs Lee, Lee Hsien Loong. Front — Lee Hsien Yang and Miss Lee Wei Ling)

Proud father at Lee Wei Ling’s “graduation”

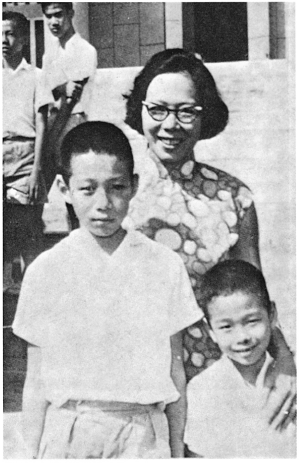

Mrs Lee Kuan Yew and the boys Hsien Loong (left) and Hsien Yang

Raffles was a young man of considerable knowledge, ability, energy and vision. He bought the island for a few silver dollars. In less than two centuries, man’s sweat and talent changed this almost deserted island into a modern, bustling city state, with tall blocks of workers’ flats, a national theatre, air-conditioned factories, up-to-date schools and universities, radio and television (including schools television), a multi-million dollar industrial complex (the largest in Southeast Asia), a network of fast highways, a parliament, and, among other features of modernity, a computered banking and commercial service without equal in the East.

Singapore has no natural resources apart from the collective ability of its population. The humidity is high and the temperature ranges between eighty-seven and seventy-five degrees fahrenheit. Copious rain falls throughout the year, the average rainfall being ninety-six inches, much of it flowing down the deep monsoon drains to the sea. Most of Singapore’s drinking water has to be bought from Johore, in Malaysia, to which Singapore is connected by a mile-long causeway. Plans were made in 1966 to enable Singapore to provide the bulk of its own drinking water by the 1970s. Singapore undoubtedly owes much of its wealth and prosperity to its unrivalled focal position in Southeast Asia on the international sea route from the Indian Ocean to the China Sea, and on the air route west and north across Asia, and east across the Pacific and southeast to Australia. Its economically strategic position at the centre of one of the world’s richest areas of natural wealth, and its deep-water harbour, have made it the natural outlet for the products of Malaysia and neighbouring countries. With its highly developed wholesale and retail commerce, banking system, insurance, shipping and storage facilities, and generations of inherited commercial skill and initiative, Singapore ranks among the greatest of the world’s commercial centres and is virtually the commercial and financial heart of the whole of Southeast Asia.

By 1970, Singapore had additionally become a fast-developing manufacturing state with its own steel mills and shipbuilding yards. An appreciable number of American and East and West European industrialists had also decided to make Singapore their regional distributive centre.

Singapore remained under British control, to some extent, if not fully (except from 1942 to 1945 when the Japanese occupied the island), from 1819 until it achieved independence. This was brought about through merger with Malaya (the hinterland which European, Chinese and Indian pioneers and capital helped enormously to develop) and with Sabah and Sarawak. Singapore, Malaya, Sabah and Sarawak became Malaysia on 16 September, 1963. The new state was acclaimed internationally as a unique experiment in multiracialism.

On 9 August, 1965, Singapore was separated from Malaysia, and became an independent and sovereign nation. A month later Singapore became the 116th member of the United Nations, and, in October, 1965, the twenty-second member of the British Commonwealth of Nations. The decision to separate Singapore from Malaysia was made by the Malaysian Government and was reluctantly accepted by the Singapore Government in order to forestall any likelihood of communal rioting which Tunku Abdul Rahman, the Malaysian Prime Minister, thought possible if they refused. The Separation Agreement provided for full co-operation between the two territories, especially in external defence and trade.

The constitutional head of the Republic, elected by Parliament in 1971, is Dr B.H. Sheares. Singapore has a parliamentary system of government based on full adult suffrage. Every citizen of twenty-one years of age and over has the right, indeed, by law, the obligation, to vote once he is registered as a voter. Malay is the national language (though Singapore is multiracial in language, education and outlook), and there are special provisions to assist the Malays: for example, the Malays are entitled to free education up to university and professional level. Members of Parliament may deliver their speeches in Malay, Mandarin, Tamil or English. There is simultaneous translation. English is the basic language of government, law and trade.

The People’s Action Party came into being in 1954 as a nationalist movement. Lee Kuan Yew, the Secretary-General, and two other members of the PAP, stood for election to the new Assembly in 1955, and won their seats easily. This Assembly of thirty-two had an elected majority of twenty-five. It was within the bounds of possibility that, had they wished, the PAP could have won most of them, but this would have meant that the party would have had to make the Constitution work, whereas they opposed the Constitution and Lee became an assemblyman in order to use the Assembly as a platform from which he could attack the Constitution and continue the struggle for complete self-government.

In 1959, largely through the efforts of Lee and his colleagues, Britain agreed to constitutional changes which did bring in a fully elected legislature and self-government. In these circumstances, the PAP was prepared to make a bid for power and the party won forty-three of the fifty-one seats. Lee Kuan Yew formed the government and became Singapore’s first Prime Minister.

It was in 1961 that Tunku Abdul Rahman, Prime Minister of the Federation of Malaya, proposed the creation of Malaysia. Singapore at once declared its full support, and at rallies and in private discussions Lee Kuan Yew and other PAP leaders helped to persuade doubters in Sabah and Sarawak. Immediately, the underground Communist Party rallied its forces in political parties, in trade unions and in the high schools and other organizations, to resist Malaysia. They mounted a powerful campaign, based upon communism and Chinese chauvinism, calling for merger between Singapore and Malaysia, a proposition which they knew the Tunku would never accept because an amalgamation of the two territories without Sabah and Sarawak would mean that the Chinese would outnumber the Malays. Lee fought for Malaysia because it would mean multiracialism; because this was the only way then that Singapore could free itself entirely from the remnant shackles of colonialism; and because Malaysia offered all the territories a chance to develop a common market of some ten million people. It was a bitter fight and the outcome was uncertain almost until the end.

Lee Kuan Yew was determined that there should never be any doubt in anybody’s mind as to exactly where the people of Singapore stood on this vital issue, and, ignoring a great deal of friendly advice which urged him not to risk his political career, Lee held a nationwide referendum. His faith was justified: seventy-one per cent of the electorate voted in favour of merger and Malaysia. In many ways it was a personal triumph for Lee. No man struggled harder for the creation of Malaysia.

Thus, on 16 September, 1963, Singapore became part of the Kingdom of Malaysia. Lee Kuan Yew remained Prime Minister of the State of Singapore, which continued to handle its own labour and education, but not the police or finance or communications. General elections were held five days later, and the people showed their appreciation of Lee’s work by returning the PAP to office (as the local government), with thirty-seven of the fifty-one seats. Less than two years later Singapore separated from Malaysia.

Lee retained the confidence of the people, and, during the next four years and more, Singapore continued to gather strength. In 1968, the PAP were again re-elected, and Lee could speak with optimism of Singapore’s future as a viable state in spite of Britain’s announcement to withdraw its military presence, and all that this meant to the nation’s economy.

But politically, Lee’s very success created considerable difficulties for parliamentary democracy. The argument is simple. Lee has produced “good government by good men”, a worthy objective in the eyes of most citizens of Chinese origin. Why, therefore, they ask, encourage an opposition which might upset that? Is not good government what the people and the nation yearn for?

This attitude, this satisfaction with things as they are, means that Lee Kuan Yew, much against his own desires, will have to face the possibility of being Prime Minister for perhaps another decade. Lee would be the first to agree that no man anywhere is indispensable. He would also resent any implication that the Republic of Singapore is in any way his own creation, either as an accidental or a deliberate piece of handiwork. Only David Marshall, the first Chief Minister, ever tried deliberately to conceive an independent Singapore outside Malaya, or Malaysia. Singapore in its present form just happened. It fell out of Malaysia, which Lee had helped to create and in which he firmly believed, because Lee and his Cabinet insisted upon a multiracial Malaysia.

“We must live in the world as we find it,” the pragmatic Lee Kuan Yew constantly reminds everyone, and he, and all those capable of thought and in possession of all the facts, know that a great deal of work still remains to be done before the survival of the Republic of Singapore, to which Lee has fully committed himself, can be assured. In these circumstances Lee will continue to serve “as a leader among other leaders”, which is how Lee Kuan Yew looks upon himself, for as long as is needed to complete the task. He never sought the Prime Minister’s job in the first place. He never schemed for power; there is no Lee Kuan Yew group in the party which keeps him in office. Since his return to Singapore in 1950, after his university days, he has been the natural nationalist leader. Not even the communists sought to displace him as leader when they tried twice to grab control of the People’s Action Party. They wanted to use him, not replace him.

Even so, Lee Kuan Yew has no intention of spending the rest of his life in office. An admirer of Sir Robert Menzies’ decision to quit as Prime Minister of Australia while at his zenith, he is determined to lay down his burden in ample time to prevent himself from becoming old and crusty with power, and to enjoy another more leisurely sort of life. He would like to write books, about Southeast Asia and about politics. It is unlikely that he will ever return to law.

Like other busy men, he finds the trappings of office convenient. There are cars, secretaries, officials, servants. They are essential if the work is to be done and appointments kept. They are part of the job. Lee has no interest in the trappings for their own sake. When he can, he dispenses with them. Like Harold Wilson, he cleans his own shoes when he has time, and happily does the odd jobs round the house which most ordinary citizens, husbands and fathers have to do.

Yet he is watchful of the dignity of his high office, of which, for the time being, he is the custodian. When he is on duty, which is most of the time except when he is with his family in his own home in Oxley Rise (he uses his official residence only for government entertainment), he is the Prime Minister, and he is conscious of his office and respects it, though power rests easily upon him. Lee never asserts himself; he has no need ever to remind anyone that he is the leader in Singapore. This is understood by every one, even by those who do not like him. Lee no longer has to remind people that he is as good as Harold Macmillan, President Nixon, or anyone else. They are now prepared to accept his judgment that he is. Unfortunately, security is a problem in a state where militant communists and racialists are not unknown, and this restricts Lee’s freedom a great deal. Armed men, trained to become part of the scenery, move with him along the golf course; the jeep which is never far away is in direct radio contact with all the other police vehicles at strategic positions on the roads near by. All this no longer bothers Lee. He shrugs his shoulders. “This,” he says, “is the world we live in.”

Sir John Nichol, then Governor of Singapore, opened the first session of the first Singapore Legislative Assembly on 22 April, 1955. He said it was an epoch in the constitutional history of Singapore. “In the period of 136 years since its establishment under the British flag as a trading centre, Singapore has been transformed from the small village which was located here, where this House of Assembly stands, to a centre of world trade with its port ranking as the tenth busiest in the world.” Ten years later, Lee Kuan Yew was speaking of Singapore as the fifth busiest port in the world.

The first business day at that first session of the first Assembly was held on 25 April. Lee Kuan Yew was on his feet minutes after it opened to protest against thanking the British Secretary of State for his Message to the Assembly. “Far be it from the People’s Action Party not to observe the civilities and courtesies of life,” he said, “but I think it is important that we should take this occasion to remind ourselves what we have to be grateful for. . .” Lee went on to move an amendment which in effect, he said, would reaffirm that the Assembly still believed that “this Constitution is no good”.

“The government of this cosmopolitan island has hitherto been in the hands of professional administrators,” Sir John Nichol had said when opening the Assembly. “Today,” he had continued, “Singapore is governed by a Council of Ministers answering to a Legislature which is predominantly popularly elected.”

“We believe,” declared Lee, “that this country is fit now for full self-government and, but for that useless, spineless lot that was supposed to represent the people of Singapore in that Constitution Commission, we would not today find ourselves with the Governor’s triumvirate, the men whom the Government has referred to as professional administrators—and no doubt they are, capable and efficient. . . we say this Constitution is a sham. We say this Constitution is colonialism in disguise. . .no one knows how long this Assembly will last, but, so long as this Assembly lasts, let it never be forgotten that there are only twenty-five men here who can stand up and say, ‘I speak for the people. I speak for the people of the constituency I represent’; that four men are here by leave and licence of His Excellency the Governor of Singapore; that they represent no one but themselves and their friends whom they are supposed to typify; and that the three professional administrators are in three pivotal positions. And we can only hope that there are men of stature on the front benches opposite, who will prove that this Constitution is not worth working and is unworkable. . .”