TWELVE years in office taught Lee Kuan Yew many things: he has become less truculent, but he is still a ready fighter, willing to take on anyone. Life is a challenge to him. He is impatient for change, but he wants to reform and hesitates to destroy in order to rebuild unless this is unavoidable: he hates poverty, and he considers it unnecessary. He does not believe that the best way to ensure that the poor have a better way of life is to provide charity. “Give a man a gold coin, and he will spend it and ask for more,” he often argues. Lee’s socialism consists mainly of a firm belief that the state must equip all with an education which will permit them to make the fullest use of their talents and abilities. Lee has never believed that all men are equal: but he insists that all men and women must be given an equal chance to make the fullest use of their own talents.

Lee is a good listener, provided the argument is an intelligent one. Journalists trying to be clever can discover a rude Lee. “Look, I’m sorry. You are talking nonsense. You have all your facts wrong. You don’t know what you are talking about. I cannot waste time talking to you.” Lee feels that time is racing ahead, and there is much to be done. He has no intention of swimming with the tide: he knows which way he wants to go and his arguments and his attitudes constantly reflect his determination to keep on that path. He does not put his faith in the abstract: he believes that God helps those who help themselves. Nothing to him is more important than attending to the present life. This makes him a realist, a materialist believing that destiny is for human beings to determine. By all means have faith, he would say, but place reliance also on hard work and deep study: most problems are man made, and man must un-make them. Lee is a perfectionist and, although he hates shoddy work, he is angered more by those who do not try. Trying is important to Lee Kuan Yew: not everyone can make the grade—that is life and nothing can change it—but everyone must be capable of making the effort.

Lee is a finicky fusser over detail, and also a political scientist who can produce visions of broad outline and wide horizons. In between expounding a theory embracing the whole of Southeast Asia, he can grumble about the fumes from diesel-driven buses, complain that his steak is not quite right, argue that the weight of a borrowed golf club caused him to hook his shot. But Lee never confuses his priorities.

Every leader manipulating power selects priorities, and in so doing concerns himself more with important decisions than with minor matters. Lee can make important decisions and stand by them. They are never made without considerable thought, reflection, consultation, and deeper thought. Once he has made a decision he stands firm, having weighed every possibility. On unimportant matters, such as arranging dates for social events, he can dither and change his mind. This can cause a great deal of inconvenience, especially if the changes are last-minute ones. Either he does not care, or, more likely, he is unaware of the detailed work involved in an altered schedule. Partly this lack of consideration for others is probably due to the fact that, ever since he has been old enough to think for himself, he has been in a position of authority. There was a brief interlude during the Japanese occupation when he, and practically everyone else in Singapore, were not in this position. Lee’s face was slapped with the rest and he, too, obediently bowed as required to his Japanese overlord. But that was different. What Lee lacks is the knowledge of what a friendly order or instruction involves. For many years, in some capacity or other, he has been accustomed to giving orders. He was too young to have been a soldier. He would have profited from the experience, for then he would have discovered that unreasonable orders cannot be carried out, even with the best will in the world. Lee’s skill and drive in achieving administrative wonders in his city state is accepted. These are problems he has carefully studied. But his impossible demands to loyal typists, for instance, to do something which nobody with twenty fingers operating a jet-driven typewriter could possibly accomplish, make people unnecessarily irritable and cause them to believe that Lee is testy and, worse, unfair.

These are small imperfections in a man suited to a more complex political situation than that afforded by a small island of less than 250 square miles, and a population of no more than two million. Lee is not a brilliant organizer, in spite of his fascination with and interest in detail, and his genuine curiosity about a wide variety of subjects, ranging from the most suitable trees to grow in parks to the best bricks to use in state-erected flats. He is a good planning general, a good surveyor of the overall scene, and, when occasion calls, a good and efficient infighter. He is intelligent enough to know that no general can fight alone. He can congratulate himself upon his talent for attracting to his side the best brains in the island. Equally important, perhaps even more important, is his success in winning the confidence of the civil service. Politicians may make the plans and give the instructions, but, in a developing state especially, nothing will happen to the best of plans and the clearest of instructions, unless there is an efficient and loyal civil service.

Lee was a most capable lawyer when he turned politician. He has a legalistic attitude towards most problems: he is, therefore, a most conservative revolutionary, but revolutionary he undoubtedly is in that he knows that the Malay peasant, and the Chinese and Indian peasant, must be introduced to modernity, “to a better and fuller life”, as he puts it. Today is the era of the transistor: most poor homes have one, and everybody knows what is happening in the outside world. Television screens, the central feature of most community centres, show what is going on. Radio and television are the great awakeners in developing countries. Lee is acutely aware of all these implications. In Singapore he controls state radio and television.

Lee is a man of considerable energy. On a long, arduous tour of Africa he was the only member of his mission not to suffer illness or complaint. This in spite of the fact that he is something of a hypochondriac, and swallows large and small pills, of many colours, every day. He catches chills easily, and carefully avoids draughts, and changes his vest and shirt whenever he feels that his body temperature is changing. He drinks a great deal of warm Chinese tea from flasks during the day, and never drinks anything chilled—not even beer.

Lee in person proves always to be as good as his remarkable reputation. This is because he makes no conscious effort to be Lee, the Asian intellectual: he behaves naturally, he never acts: he is Lee Kuan Yew all the time, in the privacy of his home and on the street corner enjoying himself haranguing the mob.

Lee Kuan Yew is a late sleeper. He normally has to be awakened about eight o’clock. He tries to get to bed before one in the morning. He surfaces slowly, but once he has bathed and had a very light breakfast, he is ready for the day’s work. He is at his best in the forenoon and prefers to take decisions then. He believes that he should concentrate hard for about three hours, and then break off for a while, preferably for an hour or two of exercise on the golf course, before going back to the evening’s work. He holds that working ten or twelve hours at a stretch may be necessary for some workers engaged on routine matters, but that it is no way for a Prime Minister of even a tiny state to organize his life. The type of work he does would, he is sure, suffer from long hours at a desk. He will come in at, say, ten o’clock, and his three personal secretaries then find their lives hardly worth living for the next three hours. Their notebooks filled, Lee may spend the next two or three hours having a swift desk lunch and seeing callers. At about three o’clock, when those who have lunched well find themselves growing sleepy (heat and humidity seem to evade even the best air-conditioners after a heavy lunch) Lee makes for the golf course. Shortly after seven he is usually back at work again, going through papers from the despatch boxes which await him at home.

Lee is aggressive, or perhaps it would be true to say he is aggressively defensive, for he is by nature and education a polite man in the Western sense (he will stand aside and permit a woman to go first, which is not yet an Oriental custom). He is not sensitive or touchy about his personal status: he can enjoy himself as one in a crowd, providing he is not on duty. Lee considers polite people civilized, and impolite and uncouth ones uncivilized and uncultured. Lee understands the need for protocol. He will, for example, go forward and greet the President of the Republic and solemnly shake hands every night of the week if state occasions, banquets, etc. demand. “These are the rules of the game,” he will say, “and they must be rigorously observed. There must be form, dignity, and no slovenliness.” Lee is not the sort of man to slap anyone on the back.

He is loyal to his friends, but his first loyalties are to his principles and to the task ahead. When a former Minister was suspiciously involved in a matter which showed poor judgment, the Prime Minister stripped him of all offices, and henceforth knew him not. They had, in the old days, been comrades fighting together. Lee never forgot this, but, when the man failed to live up to the high standards which leadership in Singapore demanded, he dismissed him and let the law take its course. This is not common in Asia. A man ceases to be Lee Kuan Yew’s friend the moment he strays from the narrow path of rectitude. In this Lee is ruthless, as he feels he must be, because of the special high position the leaders in developing states in Asia must occupy if they are to compete with the communists.

How is it that Lee Kuan Yew, a brilliant lawyer, a man professing profound regard for the rule of law, can lock up political opponents for years without a proper trial?

Lee spoke of some of the anxieties “which occasionally assail my colleagues and me about the continuance of the rule of law in newly emergent societies” at a dinner of the Singapore Advocates’ and Solicitors’ Society (18 March, 1967). Lee claimed that the fact that the rule of law was reasonably established in Singapore is cause for quiet congratulation. “It might easily have been otherwise. There were moments in 1964 and in 1965 when we felt that perhaps we were going the way of so many other places in the world.” Lee admitted that a very heavy price had been paid in order that standards should be maintained, and that there should be a Bar and judges and police to produce witnesses. “We have departed in quite a number of material aspects, in very material fields, from the principles of justice, and the liberty of the individual,” he confessed. That was the heavy price that had to be paid: “620 criminal detainees. . . 100 of whom are murderers, kidnappers and armed robbers”. Lee said that some of these cases were self-confessed and had been acquitted at trial. “To let them out would be to run the very grave risk of undermining the whole social fabric.” There were 620 criminal law supervisees, men “on whom the due processes of law were unable to place even an iota of evidence”. Lee admitted that all this was true. “We have had to adjust, to temporarily deviate from ideas and norms. This is a heavy price. We have over a hundred political detainees, men against whom we are unable to prove anything in a court of law. . . Your life and this dinner would not be what they are if my colleagues and I had decided to play it according to the rules of the game. So let us always remember that the price we have had to pay in order to maintain normal standards in the relationship between man and man, man and authority, citizen and citizen, citizen and authority is the detention of these 620 men and women under the Criminal Law Temporary Provisions Ordinance. But it is an expression of an idea when we say Temporary Provisions.”

Political prisoners are treated well in Singapore. Lim Chin Joo, younger brother of Lim Chin Siong, the communist open front leader, was arrested in 1957. Prison authorities encouraged him to study. He did, and renounced communism. When he was released in 1966 he came out a lawyer, having taken his law degree by correspondence. Today, he is the secretary of the Appeals Board under the Land Act.

Confused with the ideological struggle between the Soviet Union and China, Lim Chin Siong also renounced politics in 1969, and Lee Kuan Yew arranged for him to travel to England for medical treatment and studies.

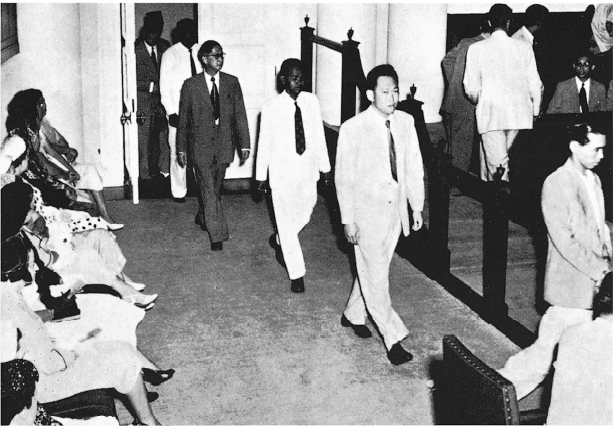

After the 1955 general elections David Marshall, who was to become Chief Minister, and Lee congratulate each other on becoming assembly-men.

22 April 1955, Lee Kuan Yew attends the first Legislative Assembly. In front of him is Lim Chin Siong, later exposed by Lee as the communist-front leader.

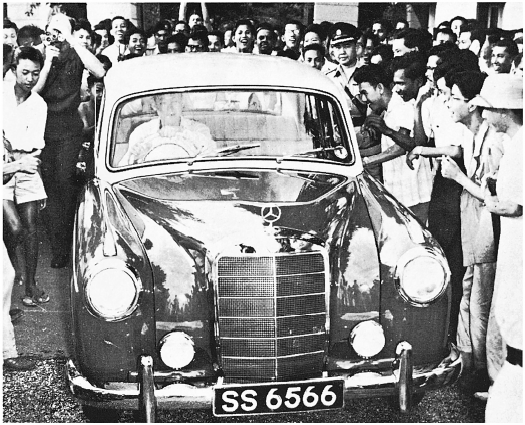

At a Press conference at the party headquarters on 1 June 1959, the secretary-general declared that “we will not form the Government unless the detainees are released”

An historic occasion, June 1959. Lee leaves the Istana after telling the Governor he will form a government providing his friends are released from prison

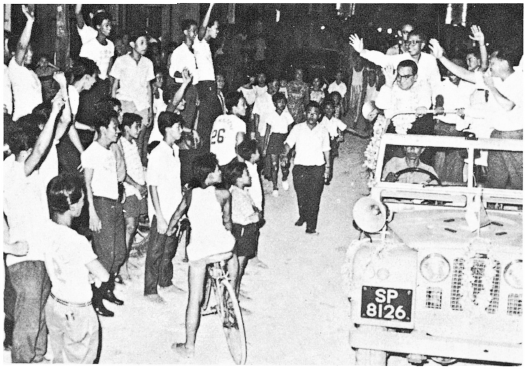

Electioning 1963

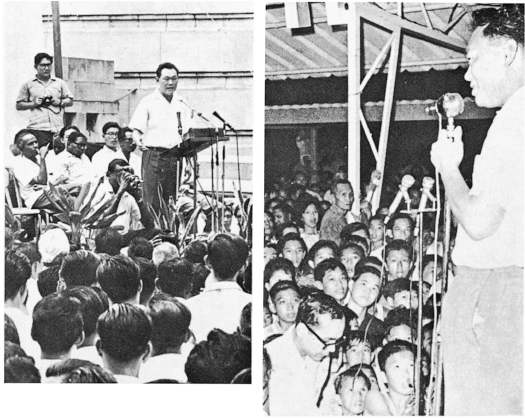

Addressing political rallies

Lee, the party man, meets supporters

Welcomed at a Malay kampong