8 |

RUNNING WITH CUNNING |

Some people no sooner master a skill than they feel a need to test their mastery in competition with others. When people with that disposition combined map-and-compass skills with cross-country running, the sport of orienteering was born.

It began in Scandinavian countries in the late 1800s as a training exercise for military officers. The first orienteering competitions open to the public were held in Norway and Sweden in the 1890s. The sport came to the United States in the 1940s but didn’t start to become popular until the 1960s. Today US orienteering clubs stage hundreds of local meets each year. Competitors gather for another twenty-five or so regional and national events as well. In Sweden, Norway, and other European countries, orienteering is a national pastime. A single big meet in Sweden can pull in as many as 15,000 enthusiasts.

In the most popular form of orienteering, competitors must find, in correct order, a series of five to fifteen control points hidden in the woods. An orange-and-white, prism-shaped structure made of fabric or cardboard marks the control point. The controls, as they are called, are either marked on the map furnished to each participant at the start of the race or copied by the participant from a master map after the starting gun sounds. The winner is the runner who finishes in the shortest time after locating all the controls. Runners who miss a control are disqualified. Easy courses may be only 1 or 2 miles long; expert-level courses can stretch 6 miles or longer. The difficulty of the terrain, and hence the time required to finish the course, can vary dramatically, however, so the length of courses can also be specified by the “expected winning time,” the time a runner with a rank of 100 in the Orienteering USA ranking system would be expected to take. The expected winning time for a “sprint” race might be twelve to fifteen minutes; the expected winning time for long-course races might be closer to one hundred minutes.

Variations on orienteering have proliferated. At some meets, rather than traveling on foot, orienteers use mountain bikes or skis or even canoes. Some orienteering competitions include relay races. Another popular variation is called score orienteering, sometimes referred to as “score O.” Here the goal is to find as many controls as possible in a set period of time rather than to find them in a specific order. More distant controls, in more difficult terrain, often earn competitors more points than closer, easier-to-find controls. A penalty point is assessed if you return late to the starting point, so the game involves strategy as well as route-finding and endurance: Can you find one more control and still make it back to the starting line before time is up? The endurance form of score orienteering, called a Rogaine, can last twenty-four hours. The odd name comes from a mashup of the early boosters’ first names, Rod, Gail, and Neil Phillips, although some people claim it stands for Rugged Outdoor Group Activity Involving Navigation and Endurance.

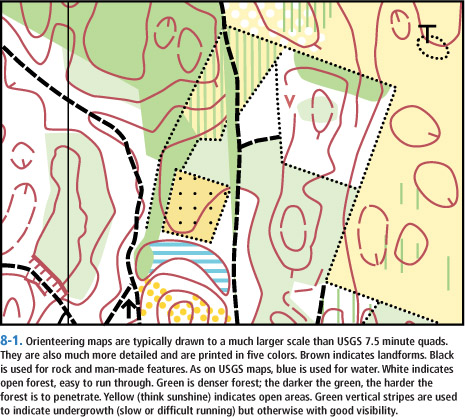

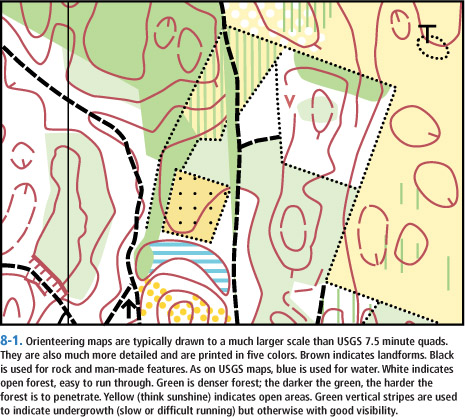

Orienteering maps (see figure 8-1) are usually drawn to a larger scale than standard USGS topos. A scale of 1:10,000 or 1:15,000 is common. The top of the map always represents magnetic north instead of geographic north, so there’s no need to worry about correcting for declination. Meet officials field-check each map as they plot the course and place the controls. They delete trails that have vanished, mark any new ones, and add the details that are one key to finding the controls: fences, boulders, knolls, tiny streams that would escape the USGS’s notice. In addition to the map, runners get a very brief description of the terrain feature at which each control point will be found.

Classic orienteering races always use a staggered start, so runners can’t simply follow each other from control to control. Ideally the controls are also placed so runners approaching a particular control get no clues from others leaving it. Score O races, including Rogaines, often use a mass start because competitors tend to fan out as they follow their own unique strategy for locating controls and accumulating points.

Only in beginner’s races will a straight-line compass course ever be the fastest way from one control to the next. Victory doesn’t necessarily go to the fastest runner. Instead it goes to the competitor who can visualize the best route from a rapid study of the map, then follow it quickly and accurately. Expert orienteers use many of the techniques I’ve already described, which in fact originated in the sport. Wherever possible, for example, they look for handrails that lead them in the right direction. Trails and roads are the most obvious handrails; power lines, fences, streams, and edges of fields are less obvious but equally effective. Over a short distance the sun can be a handrail. Perhaps you can follow your shadow or run with the sun full in your face. Or perhaps you can tell from the map that you need to follow a course that crosses the shadows thrown by trees at a 90-degree angle. With a good handrail as a guide, a runner can move out at full speed without wasting time checking map and compass.

As runners near the control, they begin searching for a catching feature crossing their path at 90 degrees to alert them to slow down and begin navigating more carefully. A catching feature can be any of the features described as potential handrails. Once runners locate the intersection of the handrail and the catching feature, they begin searching for the attack point: some relatively easy-to-find landmark close to the control. From there runners follow a precise compass bearing for a distance measured off the map. To keep track of distance, they measure the length of their stride beforehand and then count paces until they locate the control.

Good route-finding involves more than identifying handrails, catching features, and attack points. It also involves decisions about dealing with obstacles like hills, forests, and brush: over, around, or through?

As a rule of thumb, every foot of elevation gain takes as much time as running 12½ feet on the level. If your map’s contour interval is 20 feet, then climbing one contour interval takes as much time as running 250 feet on the level. You can use this rule of thumb to estimate whether it’s faster to go over a hill or around. Let’s say going over the hill involves a climb of three contour intervals (60 feet), or the equivalent of 750 feet of horizontal travel, plus 250 feet of actual horizontal travel as measured on the map. The total is 1,000 feet. If going around the hill takes less than 1,000 feet of running, it’s faster to go around. If it takes more than 1,000 feet, go over the top.

Another rule of thumb concerns the extra time required to run through vegetation and brush. Let’s say it takes 1 unit of time for you to cover 100 yards on a good trail or road. You can then estimate that it will take you 2 units of time to cover the same distance through tall grass, 3 units of time through forest with light underbrush, and 4 to 6 units of time through heavy underbrush.

If the idea of honing your route-finding skills by finding controls appeals to you but you don’t like the competitive aspect, you can attend nearly all meets and amble through the course (or a different one set up especially for people like you) at your own pace, locating the controls and punching your control card with the specially shaped punch found at each control. In orienteering jargon you’ll be known as a wayfarer or map-walker. Noncompetitive orienteering is especially popular among families with small kids.

Regular practice is the best way to perfect and maintain your map-and-compass skills. Orienteering meets provide an excellent way to do that in a safe and nonthreatening environment. With your route-finding skills nailed down, you’ll be ready to tackle a journey into the deep wilderness, confident you can not only find your way there but also find your way back home again.